39 Academic Achievement Examples

An academic achievement is any recognized success you may have achieved in an educational context, that you might be able to present on a resume or scholarship application as evidence of your academic skills and unique academic strengths .

When presenting academic achievements, it’s often the case that prestige is the most important feature. Academic institutions are very hierarchical, where awards of degrees and scholarships tend to be tiered based upon how exclusive the achievement was, and how prestigious an institution it comes from.

Nevertheless, any achievement can be presented as positive and worthy of demonstrating your academic skillset, and might give you a leg-up when interviewing for a new job. For example, oftentimes, it’s best to present a relevant achievement over and above a prestigious one.

Below are some examples of academic achievements that you could present on a resume, scholarship application, etc.

Academic Achievement Examples

Examples for undergraduates and below, 1. your school grades.

For those of you just starting out, one thing you can do is reflect back on your grades as a student in high school (for the Brits among us, your A-Levels work, or for the Americans, your AP grades).

If you got great grades in certain subjects that are highly relevant to the position you’re applying for, highlight how those subjects are your strengths, and that objective tests have demonstrated this.

2. Winning a Scholarship

Winning a scholarship, which might be as simple as one that helped pay for your books during your undergraduate degree, or as prestigious as a Rhodes Scholarship or the Fulbright Scholarship, can demonstrate that you’ve been tapped as a promising student.

List your scholarships from most to least important, and include the conferring institution and cash value of the scholarship.

When interviewed about the scholarship, discuss how it demonstrates not only your promise as a scholar, but also your potential to make meaningful contributions to your field of study or society at large.

3. Receiving an Academic Award or Prize

An academic prize or award is something you receive as recognition for your achievements or successes as a student.

For example, you might receive an award or prize that demonstrates that you were toward the top of your class, or that you were tapped as a promising student.

Also consider awards and prizes that you received for entering contests, such as essay writing contests or even a science fair.

Winning an academic award can significantly boost your profile and open up further opportunities for advancement.

4. Leadership in an Academic Club or Society

Serving in a leadership role in an academic club or society demonstrates a student’s commitment to extracurricular learning and their ability to lead others.

This might include roles such as President of the Debate Team, Editor of a university journal, or Chair of a student-led seminar series.

These roles require skills in team management, problem-solving, and communication – all of which are highly valuable in a professional setting.

5. Participation in a Study Abroad Program

Taking part in a study abroad program shows a willingness to step out of one’s comfort zone and an ability to adapt to new environments.

This experience can also indicate language skills and a global perspective, both of which are valuable in many professional settings.

In addition, study abroad programs often involve navigating complex logistics, which can demonstrate problem-solving and organizational skills , which are all desirable for future employers.

6. Tutoring or Mentoring Experience

Serving as a tutor or mentor shows a mastery of a particular subject area, as well as a commitment to helping others succeed.

This experience can also demonstrate the ability to explain complex topics in understandable ways, patience, and a propensity for leadership.

These skills are valuable in many job settings, especially roles that require clear communication, team collaboration, and management abilities.

7. Completion of an Internship or Co-op Position

Completing an internship or co-op position during undergraduate studies is a significant achievement that can help bridge the gap between academic studies and the professional world.

These experiences provide students with an opportunity to apply their academic knowledge in a real-world setting and develop professional skills.

In addition, having this experience on a resume can make a candidate more appealing to potential employers, as it indicates that they have practical experience in their field of study.

8. Certifications

Even if you haven’t been to university, you may be able to recall a time you received a certification, such as when you participated in a continuing education certification for your workplace.

Make sure it’s a certification that has some academic merit, such as requiring you to sit an exam. Even better, if you can present one that comes with an officially recognized ‘seal’ such as a red seal for a trade, you could frame this as academic, especially if you had to go to a continuing education institution and learn theory to gain this certification.

Other Undergraduate Achievement Examples:

- Class President / Class Representative

- Competitions and Contests (e.g. science fair)

- Extracurricular Activities (e.g. captain of a sports team)

- Foreign language certifications

- Leadership positions (e.g. class prefect, school captain)

- Memberships (e.g. Acceptance as a member of a student group)

- National / state awards

- Nominations for awards

- Student life participation and organization (e.g. organizing an event for a club)

- Perfect attendance award

- Sitting on the student council

- Publications in the school newspaper

- Volunteering in an academic context

Examples for Graduates

22. earning a degree.

Achieving a university degree, whether it’s an associate, bachelor’s, master’s, or doctorate, is a significant academic milestone.

This achievement is a testament to your intellectual acumen, as well as a wide range of soft skills such as determination, ability to self-regulate and manage your time, and your capacity to undertake rigorous study.

The degree subject can also reflect your area of expertise and align with the role you’re applying for, which is often the baseline for getting that interview you’re after.

When presenting your degree, mention the conferring institution and the skills you gained during your course of study. If you earned your degree with honors, be sure to mention that as well.

23. Earning a Continuing Education Certificate

Gaining a certificate through continuing education programs is another notable accomplishment. This might be a postgraduate certificate of diploma that’s not as extensive as a degree, but does show your commitment to continuing professional development.

A continuing education certificate shows your commitment to lifelong learning and your eagerness to expand your knowledge and skills.

These certificates, which can range from professional development courses to specialized skill training, signal your proactive attitude and ability to adapt to evolving industry trends.

24. Completion of a Significant Capstone Project

Many degree programs require a capstone project in the final year, which is an opportunity for students to apply and showcase the knowledge and skills they have acquired throughout their studies.

This might be an embedded honors project, or a research projected wherein you had to collect empirical evidence and present a thesis.

A successfully completed capstone project that addresses a real-world problem or contributes to a specific field of study can demonstrate that you’re able to engage in academic thinking and writing, think critically , and compose a thorough research project using a recognized qualitative or quantitative scientific methodology.

25. Graduation with Honors

Graduating with honors, such as summa cum laude, magna cum laude, or cum laude, is a significant academic achievement.

These Latin phrases, awarded based on grade point average or other academic criteria, are universally recognized symbols of academic excellence.

Graduating with honors shows a sustained commitment to hard work , intellectual growth, and academic success throughout one’s undergraduate or graduate studies.

26. Completion of a Research Assistant Project

Working as a research assistant and successfully completing a research project displays your ability to delve into complex topics, undertake detailed analysis, and contribute to the field of knowledge.

It also indicates your skills in collaboration, problem-solving, and critical thinking.

When listing this accomplishment, provide a brief overview of the project, the methodologies used, and any significant findings or results.

If your research led to a publication or presentation at a conference, make sure to include that as well.

(Note: If you want this achievement, reach out to as many professors as you can and see if they have upcoming RA positions available. Often, you’ll find there are a lot of professors wanting an RA but not actively putting out job postings for one.)

Examples for Postgraduates and Above

27. publication in a peer-reviewed journal.

Academic publishing is a significant achievement, particularly in fields where knowledge is primarily disseminated through scholarly journals.

When a student or scholar publishes original research or a review article in a reputable, peer-reviewed journal, it demonstrates their ability to conduct thorough research, critically analyze data, and contribute valuable knowledge to their field.

This achievement is highly regarded in academic and professional circles as it shows a high level of expertise and commitment to advancing the discipline.

28. Research Grant Award

Receiving a research grant, especially from a reputable institution or government body, is a significant accomplishment.

Such grants are usually awarded based on the quality and potential impact of the proposed research.

Winning a research grant indicates the recipient’s ability to design, propose, and possibly carry out valuable research in their field.

This accomplishment can provide the means to pursue further groundbreaking research, thereby bolstering the recipient’s academic standing.

29. Successful Defense of a Doctoral Thesis

Successfully defending a doctoral thesis or dissertation is an essential achievement in the journey of an academic.

This feat signifies the completion of a comprehensive piece of original research and contributes new knowledge to a field of study.

It requires years of dedication, intensive research, and critical thinking, culminating in a rigorous defense before a committee of experts in the field.

Upon successful defense, the candidate is usually awarded a doctoral degree, marking them as an authority in their area of research.

30. Acceptance into a Top-Tier Graduate Program

Gaining acceptance into a top-tier graduate program is a significant academic achievement.

Such programs are highly competitive and selective, often choosing candidates based on their academic record, research experience, and professional potential.

Being accepted into one of these programs is recognition of a student’s potential to succeed in advanced studies and make a substantial contribution to their field.

31. Presentation at a Major Conference

Being selected to present research findings at a significant academic conference is an important achievement.

These conferences gather top scholars in the field, and being chosen to present demonstrates that the research is seen as valuable and noteworthy by peers.

This accomplishment showcases the presenter’s ability to contribute meaningful discourse and their potential as a thought leader in their academic field.

32. Appointment to a University Faculty Position

Being appointed to a faculty position at a university is an academic achievement that signifies a high level of expertise and recognition in one’s field.

This position requires a record of successful research and teaching, and the competition is often intense.

Being chosen for a faculty role indicates that the university believes in the individual’s ability to contribute to the institution’s educational mission and to the advancement of knowledge in their discipline.

33. Development of a New Course or Curriculum

Designing and implementing a new course or curriculum at a university is a significant academic accomplishment.

This task requires a deep understanding of the subject matter, as well as the ability to design a structured, comprehensive, and engaging learning experience for students.

This achievement indicates a scholar’s dedication to education and their ability to contribute to improving academic programs in their field.

34. Taking a Role as Course Leader

After getting my first academic position, I told the head of my school that I wanted a course leader role as soon as one came available.

I soon was offered the position of course leader for the Masters of Education course at my university. I knew that this would look great on my resume.

A course leader role demonstrates that you can be a leader in academic contexts, overseeing a course to ensure it’s rigorous and up-to-date, and matches state or national certification requirements so that graduates can be recognized as having a degree required for getting a job in a specific field – in my situation, as teachers.

35. Guest Editing an Academic Journal Edition

Another academic achievement that I worked hard to receive in my first few years on the job was to become the guest editor for an edition of an academic journal.

I emailed academic journals and pitched my ideas, and I got one who came back to me – the Australasian Journal of Educational Technology . I edited the special issue on Cognitive Tools .

This achievement helped to establish me as someone who could successfully manage and oversee the blind peer review process, which subsequently got me a continuing job as a journal editor, which for me was the Journal of Learning Developers in Higher Education .

36. Citations to Your Publications

Citations to your publications can demonstrate that your research is having an impact in your academic community, and that it is contributing meaningfully to the field.

To find all the citations to your publications, go to google scholar and look up your name (or, create a google scholar account).

Here is mine:

Based on this, I can demonstrate that my research has achieved some traction, and this is of course a demonstrable achievement!

Other examples for postgraduates and above:

- Sitting as a Journal Editor

- Sitting as a Peer Reviewer

- Writing a Book Chapter

Even if you don’t feel you’ve had some academic achievements, it turns out once you’ve looked at the above example, you’ll likely have a few achievements under your belt. If you’re looking to advance yourself in an academic context, it’s best to stick your neck out and actively try to obtain further achievements, such as by applying for a research assistant position or working as a peer reviewer for a journal. This (often, unfortunately, underpaid work) can help you to get another step ahead of your competition when looking for a job that requires extensive academic skills.

Chris Drew (PhD)

Dr. Chris Drew is the founder of the Helpful Professor. He holds a PhD in education and has published over 20 articles in scholarly journals. He is the former editor of the Journal of Learning Development in Higher Education. [Image Descriptor: Photo of Chris]

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 10 Cognitive Dissonance Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ 10 Elaborative Rehearsal Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ Maintenance Rehearsal - Definition & Examples

- Chris Drew (PhD) https://helpfulprofessor.com/author/chris-drew-phd/ Piaget vs Vygotsky: Similarities and Differences

1 thought on “39 Academic Achievement Examples”

Thanks! I found this very helpful.

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Academic Achievement

Introduction, general overviews.

- National and International Reports

- Measuring Academic Achievement

- Intelligence

- Personality

- Students’ Familial Background

- Other Variables Predicting Academic Achievement

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Adolescence

- Changing Professional and Academic Identities

- Formative Assessment

- Gender and Achievement

- Gifted Education

- High-stakes Testing

- Learning Strategies

- Linguistically Inclusive Pedagogy

- Mathematics Instruction and Interventions for Students with Disabilities

- Methodological Approaches for Impact Evaluation in Educational Settings

- Response to Intervention

- Single-sex Education

- Standards-Based Education

- Teacher-Student Relationships

- Tracking and Detracking

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Black Women in Academia

- Girls' Education in the Developing World

- History of Education in Europe

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Academic Achievement by Ricarda Steinmayr , Anja Meißner , Anne F. Weidinger , Linda Wirthwein LAST REVIEWED: 30 July 2014 LAST MODIFIED: 30 July 2014 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199756810-0108

Academic achievement represents performance outcomes that indicate the extent to which a person has accomplished specific goals that were the focus of activities in instructional environments, specifically in school, college, and university. School systems mostly define cognitive goals that either apply across multiple subject areas (e.g., critical thinking) or include the acquisition of knowledge and understanding in a specific intellectual domain (e.g., numeracy, literacy, science, history). Therefore, academic achievement should be considered to be a multifaceted construct that comprises different domains of learning. Because the field of academic achievement is very wide-ranging and covers a broad variety of educational outcomes, the definition of academic achievement depends on the indicators used to measure it. Among the many criteria that indicate academic achievement, there are very general indicators such as procedural and declarative knowledge acquired in an educational system, more curricular-based criteria such as grades or performance on an educational achievement test, and cumulative indicators of academic achievement such as educational degrees and certificates. All criteria have in common that they represent intellectual endeavors and thus, more or less, mirror the intellectual capacity of a person. In developed societies, academic achievement plays an important role in every person’s life. Academic achievement as measured by the GPA (grade point average) or by standardized assessments designed for selection purpose such as the SAT (Scholastic Assessment Test) determines whether a student will have the opportunity to continue his or her education (e.g., to attend a university). Therefore, academic achievement defines whether one can take part in higher education, and based on the educational degrees one attains, influences one’s vocational career after education. Besides the relevance for an individual, academic achievement is of utmost importance for the wealth of a nation and its prosperity. The strong association between a society’s level of academic achievement and positive socioeconomic development is one reason for conducting international studies on academic achievement, such as PISA (Programme for International Student Assessment), administered by the OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development). The results of these studies provide information about different indicators of a nation’s academic achievement; such information is used to analyze the strengths and weaknesses of a nation’s educational system and to guide educational policy decisions. Given the individual and societal importance of academic achievement, it is not surprising that academic achievement is the research focus of many scientists; for example, in psychology or educational disciplines. This article focuses on the explanation, determination, enhancement, and assessment of academic achievement as investigated by educational psychologists.

The exploration of academic achievement has led to numerous empirical studies and fundamental progress such as the development of the first intelligence test by Binet and Simon. Introductory textbooks such as Woolfolk 2007 provide theoretical and empirical insight into the determinants of academic achievement and its assessment. However, as academic achievement is a broad topic, several textbooks have focused mainly on selected aspects of academic achievement, such as enhancing academic achievement or specific predictors of academic achievement. A thorough, short, and informative overview of academic achievement is provided in Spinath 2012 . Spinath 2012 emphasizes the importance of academic achievement with regard to different perspectives (such as for individuals and societies, as well as psychological and educational research). Walberg 1986 is an early synthesis of existing research on the educational effects of the time but it still influences current research such as investigations of predictors of academic achievement in some of the large-scale academic achievement assessment studies (e.g., Programme for International Student Assessment, PISA). Walberg 1986 highlights the relevance of research syntheses (such as reviews and meta-analyses) as an initial point for the improvement of educational processes. A current work, Hattie 2009 , provides an overview of the empirical findings on academic achievement by distinguishing between individual, home, and scholastic determinants of academic achievement according to theoretical assumptions. However, Spinath 2012 points out that it is more appropriate to speak of “predictors” instead of determinants of academic achievement because the mostly cross-sectional nature of the underlying research does not allow causal conclusions to be drawn. Large-scale scholastic achievement assessments such as PISA (see OECD 2010 ) provide an overview of the current state of research on academic achievement, as these studies have investigated established predictors of academic achievement on an international level. Furthermore, these studies, for the first time, have enabled nations to compare their educational systems with other nations and to evaluate them on this basis. However, it should be mentioned critically that this approach may, to some degree, overestimate the practical significance of differences between the countries. Moreover, the studies have increased the amount of attention paid to the role of family background and the educational system in the development of individual performance. The quality of teaching, in particular, has been emphasized as a predictor of student achievement. Altogether, there are valuable cross-sectional studies investigating many predictors of academic achievement. A further focus in educational research has been placed on tertiary educational research. Richardson, et al. 2012 subsumes the individual correlates of university students’ performance.

Hattie, John A. C. 2009. Visible learning: A synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement . London: Routledge.

A quantitative synthesis of 815 meta-analyses covering English-speaking research on the achievement of school-aged students. According to Hattie, the influences of quality teaching represent the most powerful determinants of learning. Thereafter, Hattie published Visible Learning for Teachers (London and New York: Routledge, 2012) so that the results could be transferred to the classroom.

OECD. 2010. PISA 2009 key findings . Vols. 1–6.

These six volumes illustrate the results of the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) 2009—the most extensive international scholastic achievement assessment—regarding the competencies of fifteen-year-old students all over the world in reading, mathematics, and science. Furthermore, the presented results cover the effects of student learning behavior, social background, and scholastic resources. Unlimited online access.

Richardson, Michelle, Charles Abraham, and Rod Bond. 2012. Psychological correlates of university students’ academic performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin 138:353–387.

DOI: 10.1037/a0026838

A current and comprehensive review concerning the prediction of university students’ performance, illustrating self-efficacy to be the strongest correlate of tertiary grade point average (GPA). Cognitive constructs (high school GPA, American College Test), as well as further motivational factors (grade goal, academic self-efficacy) have medium effect sizes.

Spinath, Birgit. 2012. Academic achievement. In Encyclopedia of human behavior . 2d ed. Edited by Vilanayur S. Ramachandran, 1–8. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

A current introduction to academic achievement, subsuming research on indicators and predictors of achievement as well as reasons for differences in education caused by gender and socioeconomic resources. The chapter provides further references on the topic.

Walberg, Herbert J. 1986. Syntheses of research on teaching. In Handbook of research on teaching . 3d ed. Edited by Merlin C. Wittrock, 214–229. New York: Macmillan.

A quantitative and qualitative aggregation of a variety of reviews and quantitative syntheses as an overview of early research on educational outcomes. Walberg found nine factors to be central to the determination of school learning.

Woolfolk, Anita. 2007. Educational psychology . 10th ed. Boston: Pearson.

Woolfolk represents a comprehensive basic work that is founded on an understandable and practical communication of knowledge. The perspectives of students as scholastic learners as well as teachers are the focus of attention. Suitable for undergraduate and graduate students. Currently presented in the 12th edition.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Education »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Academic Achievement

- Academic Audit for Universities

- Academic Freedom and Tenure in the United States

- Action Research in Education

- Adjuncts in Higher Education in the United States

- Administrator Preparation

- Advanced Placement and International Baccalaureate Courses

- Advocacy and Activism in Early Childhood

- African American Racial Identity and Learning

- Alaska Native Education

- Alternative Certification Programs for Educators

- Alternative Schools

- American Indian Education

- Animals in Environmental Education

- Art Education

- Artificial Intelligence and Learning

- Assessing School Leader Effectiveness

- Assessment, Behavioral

- Assessment, Educational

- Assessment in Early Childhood Education

- Assistive Technology

- Augmented Reality in Education

- Beginning-Teacher Induction

- Bilingual Education and Bilingualism

- Black Undergraduate Women: Critical Race and Gender Perspe...

- Blended Learning

- Case Study in Education Research

- Character Education

- Children’s and Young Adult Literature

- Children's Beliefs about Intelligence

- Children's Rights in Early Childhood Education

- Citizenship Education

- Civic and Social Engagement of Higher Education

- Classroom Learning Environments: Assessing and Investigati...

- Classroom Management

- Coherent Instructional Systems at the School and School Sy...

- College Admissions in the United States

- College Athletics in the United States

- Community Relations

- Comparative Education

- Computer-Assisted Language Learning

- Computer-Based Testing

- Conceptualizing, Measuring, and Evaluating Improvement Net...

- Continuous Improvement and "High Leverage" Educational Pro...

- Counseling in Schools

- Critical Approaches to Gender in Higher Education

- Critical Perspectives on Educational Innovation and Improv...

- Critical Race Theory

- Crossborder and Transnational Higher Education

- Cross-National Research on Continuous Improvement

- Cross-Sector Research on Continuous Learning and Improveme...

- Cultural Diversity in Early Childhood Education

- Culturally Responsive Leadership

- Culturally Responsive Pedagogies

- Culturally Responsive Teacher Education in the United Stat...

- Curriculum Design

- Data Collection in Educational Research

- Data-driven Decision Making in the United States

- Deaf Education

- Desegregation and Integration

- Design Thinking and the Learning Sciences: Theoretical, Pr...

- Development, Moral

- Dialogic Pedagogy

- Digital Age Teacher, The

- Digital Citizenship

- Digital Divides

- Disabilities

- Distance Learning

- Distributed Leadership

- Doctoral Education and Training

- Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC) in Denmark

- Early Childhood Education and Development in Mexico

- Early Childhood Education in Aotearoa New Zealand

- Early Childhood Education in Australia

- Early Childhood Education in China

- Early Childhood Education in Europe

- Early Childhood Education in Sub-Saharan Africa

- Early Childhood Education in Sweden

- Early Childhood Education Pedagogy

- Early Childhood Education Policy

- Early Childhood Education, The Arts in

- Early Childhood Mathematics

- Early Childhood Science

- Early Childhood Teacher Education

- Early Childhood Teachers in Aotearoa New Zealand

- Early Years Professionalism and Professionalization Polici...

- Economics of Education

- Education For Children with Autism

- Education for Sustainable Development

- Education Leadership, Empirical Perspectives in

- Education of Native Hawaiian Students

- Education Reform and School Change

- Educational Statistics for Longitudinal Research

- Educator Partnerships with Parents and Families with a Foc...

- Emotional and Affective Issues in Environmental and Sustai...

- Emotional and Behavioral Disorders

- English as an International Language for Academic Publishi...

- Environmental and Science Education: Overlaps and Issues

- Environmental Education

- Environmental Education in Brazil

- Epistemic Beliefs

- Equity and Improvement: Engaging Communities in Educationa...

- Equity, Ethnicity, Diversity, and Excellence in Education

- Ethical Research with Young Children

- Ethics and Education

- Ethics of Teaching

- Ethnic Studies

- Evidence-Based Communication Assessment and Intervention

- Family and Community Partnerships in Education

- Family Day Care

- Federal Government Programs and Issues

- Feminization of Labor in Academia

- Finance, Education

- Financial Aid

- Future-Focused Education

- Gender and Alternative Education

- Gender, Power and Politics in the Academy

- Gender-Based Violence on University Campuses

- Global Mindedness and Global Citizenship Education

- Global University Rankings

- Governance, Education

- Grounded Theory

- Growth of Effective Mental Health Services in Schools in t...

- Higher Education and Globalization

- Higher Education and the Developing World

- Higher Education Faculty Characteristics and Trends in the...

- Higher Education Finance

- Higher Education Governance

- Higher Education Graduate Outcomes and Destinations

- Higher Education in Africa

- Higher Education in China

- Higher Education in Latin America

- Higher Education in the United States, Historical Evolutio...

- Higher Education, International Issues in

- Higher Education Management

- Higher Education Policy

- Higher Education Research

- Higher Education Student Assessment

- History of Early Childhood Education in the United States

- History of Education in the United States

- History of Technology Integration in Education

- Homeschooling

- Inclusion in Early Childhood: Difference, Disability, and ...

- Inclusive Education

- Indigenous Education in a Global Context

- Indigenous Learning Environments

- Indigenous Students in Higher Education in the United Stat...

- Infant and Toddler Pedagogy

- Inservice Teacher Education

- Integrating Art across the Curriculum

- Intensive Interventions for Children and Adolescents with ...

- International Perspectives on Academic Freedom

- Intersectionality and Education

- Knowledge Development in Early Childhood

- Leadership Development, Coaching and Feedback for

- Leadership in Early Childhood Education

- Leadership Training with an Emphasis on the United States

- Learning Analytics in Higher Education

- Learning Difficulties

- Learning, Lifelong

- Learning, Multimedia

- Legal Matters and Education Law

- LGBT Youth in Schools

- Linguistic Diversity

- Literacy Development and Language Acquisition

- Literature Reviews

- Mathematics Identity

- Mathematics Instruction and Interventions for Students wit...

- Mathematics Teacher Education

- Measurement for Improvement in Education

- Measurement in Education in the United States

- Meta-Analysis and Research Synthesis in Education

- Methodological Approaches for Impact Evaluation in Educati...

- Methodologies for Conducting Education Research

- Mindfulness, Learning, and Education

- Mixed Methods Research

- Motherscholars

- Multiliteracies in Early Childhood Education

- Multiple Documents Literacy: Theory, Research, and Applica...

- Multivariate Research Methodology

- Museums, Education, and Curriculum

- Music Education

- Narrative Research in Education

- Native American Studies

- Nonformal and Informal Environmental Education

- Note-Taking

- Numeracy Education

- One-to-One Technology in the K-12 Classroom

- Online Education

- Open Education

- Organizing for Continuous Improvement in Education

- Organizing Schools for the Inclusion of Students with Disa...

- Outdoor Play and Learning

- Outdoor Play and Learning in Early Childhood Education

- Pedagogical Leadership

- Pedagogy of Teacher Education, A

- Performance Objectives and Measurement

- Performance-based Research Assessment in Higher Education

- Performance-based Research Funding

- Phenomenology in Educational Research

- Philosophy of Education

- Physical Education

- Podcasts in Education

- Policy Context of United States Educational Innovation and...

- Politics of Education

- Portable Technology Use in Special Education Programs and ...

- Post-humanism and Environmental Education

- Pre-Service Teacher Education

- Problem Solving

- Productivity and Higher Education

- Professional Development

- Professional Learning Communities

- Program Evaluation

- Programs and Services for Students with Emotional or Behav...

- Psychology Learning and Teaching

- Psychometric Issues in the Assessment of English Language ...

- Qualitative Data Analysis Techniques

- Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Research Samp...

- Qualitative Research Design

- Quantitative Research Designs in Educational Research

- Queering the English Language Arts (ELA) Writing Classroom

- Race and Affirmative Action in Higher Education

- Reading Education

- Refugee and New Immigrant Learners

- Relational and Developmental Trauma and Schools

- Relational Pedagogies in Early Childhood Education

- Reliability in Educational Assessments

- Religion in Elementary and Secondary Education in the Unit...

- Researcher Development and Skills Training within the Cont...

- Research-Practice Partnerships in Education within the Uni...

- Restorative Practices

- Risky Play in Early Childhood Education

- Scale and Sustainability of Education Innovation and Impro...

- Scaling Up Research-based Educational Practices

- School Accreditation

- School Choice

- School Culture

- School District Budgeting and Financial Management in the ...

- School Improvement through Inclusive Education

- School Reform

- Schools, Private and Independent

- School-Wide Positive Behavior Support

- Science Education

- Secondary to Postsecondary Transition Issues

- Self-Regulated Learning

- Self-Study of Teacher Education Practices

- Service-Learning

- Severe Disabilities

- Single Salary Schedule

- Single-Subject Research Design

- Social Context of Education

- Social Justice

- Social Network Analysis

- Social Pedagogy

- Social Science and Education Research

- Social Studies Education

- Sociology of Education

- Statistical Assumptions

- Student Access, Equity, and Diversity in Higher Education

- Student Assignment Policy

- Student Engagement in Tertiary Education

- Student Learning, Development, Engagement, and Motivation ...

- Student Participation

- Student Voice in Teacher Development

- Sustainability Education in Early Childhood Education

- Sustainability in Early Childhood Education

- Sustainability in Higher Education

- Teacher Beliefs and Epistemologies

- Teacher Collaboration in School Improvement

- Teacher Evaluation and Teacher Effectiveness

- Teacher Preparation

- Teacher Training and Development

- Teacher Unions and Associations

- Teaching Critical Thinking

- Technologies, Teaching, and Learning in Higher Education

- Technology Education in Early Childhood

- Technology, Educational

- Technology-based Assessment

- The Bologna Process

- The Regulation of Standards in Higher Education

- Theories of Educational Leadership

- Three Conceptions of Literacy: Media, Narrative, and Gamin...

- Traditions of Quality Improvement in Education

- Transformative Learning

- Transitions in Early Childhood Education

- Tribally Controlled Colleges and Universities in the Unite...

- Understanding the Psycho-Social Dimensions of Schools and ...

- University Faculty Roles and Responsibilities in the Unite...

- Using Ethnography in Educational Research

- Value of Higher Education for Students and Other Stakehold...

- Virtual Learning Environments

- Vocational and Technical Education

- Wellness and Well-Being in Education

- Women's and Gender Studies

- Young Children and Spirituality

- Young Children's Learning Dispositions

- Young Children's Working Theories

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [66.249.64.20|185.147.128.134]

- 185.147.128.134

If you're seeing this message, it means we're having trouble loading external resources on our website.

If you're behind a web filter, please make sure that the domains *.kastatic.org and *.kasandbox.org are unblocked.

To log in and use all the features of Khan Academy, please enable JavaScript in your browser.

College admissions

Course: college admissions > unit 4.

- Writing a strong college admissions essay

- Avoiding common admissions essay mistakes

- Brainstorming tips for your college essay

- How formal should the tone of your college essay be?

- Taking your college essay to the next level

Sample essay 1 with admissions feedback

- Sample essay 2 with admissions feedback

- Student story: Admissions essay about a formative experience

- Student story: Admissions essay about personal identity

- Student story: Admissions essay about community impact

- Student story: Admissions essay about a past mistake

- Student story: Admissions essay about a meaningful poem

- Writing tips and techniques for your college essay

Introduction

Sample essay 1, feedback from admissions.

Want to join the conversation?

- Upvote Button navigates to signup page

- Downvote Button navigates to signup page

- Flag Button navigates to signup page

CONCEPTUAL ANALYSIS article

Fostering efl/esl students’ language achievement: the role of teachers’ enthusiasm and classroom enjoyment.

- 1 College of Foreign Languages, Hebei Agricultural University, Baoding, China

- 2 Department of English, Hebei University of Chinese Medicine, Shijiazhuang, China

Thanks to the inflow of positive psychology (PP) in language education in general and language learning in particular, extensive consideration has been drawn to the role of emotion in second language acquisition (SLA). Enjoyment as a mutual constructive sensation experienced by students has engrossed academic attention. Likewise, teachers are redirected as the most remarkable figure of any educational association, and their enthusiasm is substantial for students in the classroom. In line with the inquiries of teacher enthusiasm, principles of PP, and classroom enjoyment, the current review strives for this form of connection and its impacts on learners’ achievement. Subsequently, the suggestions of this review for teachers, learners, and educator trainers are deliberated.

Introduction

A central objective of colleges is learners’ achievement and success, whose administration routes should pay great attention to observing learners’ educational performance. As a result, through institutional- and framework-level administration provisions, the quality of learners’ education should be taken into consideration ( Jones, 2013 ). Generally measured with tests, scholastic achievement alludes to what exactly is done under existing conditions that incorporates the most common way of editing and using the construction of information and capacities and a large group of emotional, inspirational, and complex factors that impact definitive reactions ( O’Donnell and White, 2005 ). Academic achievement is defined as the perceived and assessed part of a learner’s mastery of abilities and subject materials as estimated with legitimate and valid tests ( Joe et al., 2014 ). Based on Nurhasanah and Sobandi (2016) , there might be two kinds of factors, internal and external, which influence learning performance and learning success. In addition to issues, such as health, impairments, and cognitive elements (intelligence, aptitude, enthusiasm, concentration, motivation, and fatigue). While learners’ academic achievement and success are influenced by many external elements, including family members, educational environments, and cultural considerations, learner performance and achievement will be affected by these two internal and external elements.

On the significance of feelings in language learning, a great amount of the literature mentioned that feelings assume an indispensable part in students’ performances in a foreign language ( MacIntyre and Vincze, 2017 ; Shao et al., 2019 ). There has been developing attention to feelings in language settings, all the more explicitly, in the way they influence language students’ motivation, praise, interest, commitment, practice, accomplishment, and well-being ( Dewaele et al., 2019 ; MacIntyre et al., 2019 ; Dewaele and Li, 2021 ). Additionally, charged by the introduction of positive psychology (PP) in second language acquisition (SLA; MacIntyre and Gregersen, 2012 ) was the term “affective turn” ( Pavlenko, 2013 ; Prior, 2019 ). Past research acknowledges the effect of negative emotions on language accomplishment ( Ostafin et al., 2014 ; Ford et al., 2019 ).

Nonetheless, dependent on the PP development in instruction, there has lately been a growing extent of the literature on constructive emotions in SLA ( Dewaele and MacIntyre, 2014 ; MacIntyre et al., 2019 ; Wang et al., 2021 ) provoking analysts to move their enduring attention from negative emotions (L2 stress and boredom) to positive ones (L2 satisfaction; Khajavy et al., 2018 ; Dewaele et al., 2019 ; Derakhshan et al., 2021 ; Dewaele and Li, 2021 ). As opposed to negative emotions, which trigger limited attitudes, positive emotions encourage the expansion of mentalities and discovery of inventive and novel notions, which can prompt the foundation of one’s physical, mental, scholarly, and social assets ( Fredrickson, 2004 ). Moreover, positive emotions are helpful for individual investigation, permitting one to procure new experiences and learn successfully ( Dewaele and MacIntyre, 2014 ; Xie and Derakhshan, 2021 ).

Accordingly, the range of emotion has been extended past stress to incorporate happiness, love, pride, trust, guilt, disgrace, fatigue, outrage, disappointment, and so on ( Kruk and Zawodniak, 2018 ; Pavelescu and Petric, 2018 ; MacIntyre et al., 2019 ). Among all types of emotions, either negative or positive inspected in the language research trend, Foreign Language Enjoyment (FLE) has been viewed as the most regularly knowledgeable emotional aspect for students ( Piniel and Albert, 2018 ). Classroom enjoyment is perceived as the degree to which L2 learning is regarded as providing joy ( Dewaele and MacIntyre, 2014 ), which is a constructive emotional state that consolidates challenge, bliss, interest, fun, feeling of pride, and feeling of importance. It happens particularly in exercises where students have a level of independence and when something new or difficult is accomplished ( Csikszentmihalyi and Seligman, 2000 ). FLE had jointly caught great attention for its critical ramifications for L2 results ( Jin and Zhang, 2018 ; Li et al., 2018 ). It was figuratively theorized as the emotional feet of each L2 student for their prevalence in the L2 learning setting ( Dewaele and MacIntyre, 2016 ). In a foreign language setting, enjoyment was picked as a positive equivalent of the broadly studied negative emotion of FLA generally since it is a center part of the foundational notion of PP, i.e., flow ( Csikszentmihalyi, 2014 ).

Furthermore, supported by the broaden-and-build hypothesis, enjoyment is a progressive and emotion-focused action, one that decidedly impacts students’ scholarly presentation and it is an idea that resounds with the arising field of PP ( Pekrun et al., 2007 ; Pekrun and Perry, 2014 ). The primary principle of broaden-and-build is that positive emotion, like enjoyment, can expand people’s thought-action collections and create their mental versatility and individual assets ( Fredrickson, 2003 ; Oxford, 2015 ). Regarding SLA, it is contended that students encountering constructive emotions will assimilate more information and will create more assets for more language education. Conversely, negative emotions will limit students’ concentration and the scope of possible language input. Enjoyment, however, is effective in expanding students’ thought-action collection to assimilate more in language learning and assist them with building language assets ( MacIntyre and Gregersen, 2012 ). In addition, according to the control-value hypothesis ( Pekrun, 2006 ), FLE is a constructive accomplishment emotion with high motivation emerging from progressive learning action or assignment. It has constructive outcomes for different L2 learning results encompassing L2 motivation, commitment, and learning accomplishment ( Li, 2020 ; Dewaele and Li, 2021 ). Since FLE urges students to be innovative and investigate a new language, it triggers foreign language learning ( Dewaele and MacIntyre, 2016 ). Numerous past studies have additionally discovered that enjoyment is commonly connected with less stress and higher educational fulfillment ( Dewaele and Dewaele, 2017 ). Latest movements in PP, nonetheless, have prompted an expansion of studies intended to stimulate the significance of language erudition being triggered by positive emotions, regarding the latter as an enhancer and the main impetus behind SLA ( Oxford, 2015 ). It has been discovered up to date that FLE is positively connected with high scholarly achievement and proficiency in a foreign language ( Hagenauer and Hascher, 2014 ; Dewaele and Alfawzan, 2018 ; Dewaele et al., 2019 ).

Moreover, in comparison with classroom enjoyment, teacher enthusiasm had a noteworthy impact on student-perceived teaching quality. The attitude toward something, generally a nonverbal practice of expressiveness, is known as enthusiasm. Thus, it is characterized as learners’ positive affective qualities, satisfaction, and joy during learning ( Kunter et al., 2011 ). It is a quality-like, constant, and repeating feeling. Since enthusiasm pushes the learner to study and to receive the new cycle being experienced, it cannot be separated from a learning cycle. With enthusiasm, the learners show their delight in learning English by displaying their joyful facial expressions in the class and have a positive sentiment to learning a language. When learning something new like the English language, learners get excited. Enthusiasm can positively impact learners’ results ( Patrick et al., 2000 ). The greater the learners’ enthusiasm in learning a language, the greater the results and the achievements they will encounter in learning.

Enthusiasm, as a significant quality for everyone, pays little heed to the type of work being done. To put it simply, an enthusiastic individual is a person who, in a real sense, is motivated by a strong force. Moreover, the motivated individual comes to perceive himself as a distinguished top pick of the divine nature. When this craze happens, which is the culmination of energy, each fanciful notion is accentuated ( Nur, 2019 ). Educator enthusiasm could be characterized as the occurrence of assorted behavioral articulations, like, nonverbal (gestures) and verbal (tone of voice) practices ( Keller et al., 2016 ).

The prior inquiries were conducted with respect to FLE in higher education ( Dewaele et al., 2016 ; Dewaele and MacIntyre, 2016 ; Elahi Shirvan and Talebzadeh, 2018 ; Li et al., 2018 ; Talebzadeh et al., 2020 ). In addition, former studies have presented that teacher enthusiasm is connected to diverse constructive consequences, such as students’ enjoyment, interest, achievement, motivation, and vitality ( Patrick et al., 2000 ; Kunter et al., 2013 ; Keller et al., 2014 ; König and Jucks, 2019 ). Although these investigations have been done in these domains, this review makes an effort to inspect the function of classroom enjoyment and teacher enthusiasm on learners’ achievement in foreign language learning.

Teacher Enthusiasm

Perceived to be a fundamental component for enhancing teaching results is educator enthusiasm, which is quite possibly the main attribute of successful teachers ( Kunter et al., 2011 ; Ruzek et al., 2016 ). Enthusiasm is a feeling based on sensory perception, providing the ability to detect, acknowledge, evaluate, or respond physically to something. A powerful stimulus can create excitement, which results in enjoyment or satisfaction in a particular activity. These definitions are described in terms of their causes and effects ( Setianingsih and Nafisah, 2021 ). There is a theoretical explanation that enthusiasm promotes the attention of educators to their learners in the classroom ( Kunter and Holzberger, 2014 ) and enhances constructive effect in learners by sharing emotive responses ( Frenzel et al., 2018 ) resulting in improved learner relationships and a reduction in conflict ( Kunter et al., 2013 ). Teacher enthusiasm is delineated as a nonverbal manifestation that the educator echoes ( Baloch and Akram, 2018 ); teacher performances like presenting effective demonstrations, facilitating interaction, and communication ( Hadie et al., 2019 ; Wang and Derakhshan, 2021 ); teachers’ distinctive features in line with the constructive emotional state ( Keller et al., 2018 ); and constructive emotive practices that the educator achieves while carrying out her/his responsibility ( Keller et al., 2014 ).

Enthusiasm is an individual’s feeling of getting energized, while acting and it is developed when she/he begins to be interested in the activity. Moreover, it can be characterized as a strong liking for a subject of matter, something, or activity, and a searing soul, fuel, or the blasting fire of something new. Learners regard enthusiasm as the focus of their learning and a prerequisite for their involvement ( Pithers and Holland, 2006 ). Moreover, Kunter et al. (2011) categorized enthusiasm as an emotional-behavioral educator quality. The multiple-dimensional structure includes both a learner’s sense of pleasure, enjoyment, and interest, as well as specific learning activities that promote these feelings in the educational setting. Moreover, it was found that teachers’ enthusiasm for the subject was distinct from their enthusiasm for teaching activities. Keller et al. (2016) described educator engagement as both an emotional and cognitive quality consisting of a favorable psychological state, a sense of enjoyment, and happiness, as well as the exhibiting of specific behaviors (primarily physical) derived from them. Feeling enthusiasm and showing enthusiasm constitute enthusiasm, respectively. By proposing that educator enthusiasm is the emotional experience of pleasure during learning as well as its actions or expression during education, Frenzel et al. (2009) developed this theory. Educators’ expressions of enjoyment include smiles, widening eyes, and a mutable tone, and greater speed. Teacher enthusiasm that could be transferred to learners, boost their enthusiasm, participation, and commitment ( Lazarides et al., 2019 ).

Enjoyment occurs when learners perceive themselves to be competent at performing an educational task as well as recognizing the content of the learning process ( Mierzwa, 2019 ). An enjoyment construct comprises five categories: behavioral, mental, emotional, expressional, and psychological ( Hagenauer and Hascher, 2014 ). In the same way that the name implies, the affective component of enjoyment focuses on emotions, and in particular, on the sense of satisfaction and pleasure felt during the learning process. Additionally, the mental aspect of learning is concerned with evaluating the situation positively. Hence, enjoyment could be considered the feeling of accomplishment that arises when completing a challenging, complex task that encourages inquiry ( Pekrun et al., 2007 ) and creates enthusiasm ( Ainley and Hidi, 2014 ; Han and Wang, 2021 ). Moreover, the motivational aspect of enjoyment refers to learners’ ability to feel good by encouraging them, emotionally and physically, to attempt more FL tasks in the future ( Villavicencio and Bernardo, 2013 ). Since Broaden-and-Build Theory of constructive emotions of Fredrickson (2001) and the Control-Value Theory of emotions ( Pekrun and Perry, 2014 ) both explain how positive emotions appear, it is logical to expect that FLE will perform similarly within the FL context and is deemed as a major source of positive achievement feelings that are directly linked with the enjoyment of flow.

The concept of FLE was introduced by MacIntyre and Gregersen (2012) , explaining how the construct of enjoyment as a feeling associated with achievement could help learners develop resources to learn English more effectively ( Pekrun, 2006 ), enhance their understanding, and improve their motivation in academic learning ( Jin and Zhang, 2019 ). FLE is significantly affected by its educational process, such as the connections with thoughtful and cooperative classmates, as well as the communication with enthusiastic language educators that provide a variety of engaging and challenging classroom activities to engage learners ( Pavelescu and Petric, 2018 ). There are two scopes of enjoyment in FLE: first, FLE is linked to the educator (teaching methods, encouragement, optimism, and educator acknowledgment); second, FLE is associated with the environment in FL education (social contacts, enthusiasm, and motivation; Li et al., 2018 ). A third dimension that is not less important than the two aforementioned is FLE-private coalescing with its contribution to personal development and personal progress. Among the sources of FLE-private, the following can be eminent: realizing one’s progress, achieving great FL results, achieving success, and observing improvements in FL learning ( Li et al., 2018 ).

Implications and Future Directions

This review has provided some suggestions for language stakeholders. It can be of significance for educators, pupils, and educator trainers. Various studies have found that FLE is a motivational force that impacts language learning in several ways as it enables higher academic achievement, enhances motivation, and may even protect individuals against negatively framed views ( MacIntyre, 2016 ). In this sense, FLE provides a useful experience for educational purposes and might be essential for learners to achieve full proficiency in multiple languages. Corresponding to the Control-Value Theory, learners’ ability to internalize values of academic engagement and achievement is likely to be enhanced when their educators demonstrate enthusiasm and enjoyment regarding a particular subject or learning activity ( Pekrun, 2006 ; Derakhshan, 2021 ).

The present review can be valuable for language learners as they can have less anxiety and become more confident and autonomous when facing challenges in the classroom when their educators are enthusiastic. It has been found that enthusiasm can have a major impact on educational success, so it is evident that enthusiasm has a significant effect on learners’ performance and helps them to be successful in academic learning. The educator’s enthusiasm ensures they intend to go above and beyond to fulfill their professional duties, as well as give the correct clues to their learners. As a result, an enthusiastic educator can be defined as one who seeks to accomplish the teaching and learning process effectively and performs his or her duty of supporting the learners as needed for successful teaching and learning. Furthermore, it is the teacher’s concern to control the emotional atmosphere of the classroom, to nurture a positive sense among the students, and, ideally, to teach with excitement, enthusiasm, and interest ( Dewaele et al., 2018 ).

The enthusiasm of the educators will make a difference not only on the learning side, but also during the educational process since educators organize these activities ( Bedir and Yıldırım, 2000 ). An educator should be enthusiastic when performing the teaching duties given to her/him. An educator should adjust the course and tone of voice according to the learners’ interests and abilities during the presentation to ensure that the course is engaging for the learners and demonstrates their enthusiasm for the course ( Keller et al., 2016 ).

Learners who are imitating an enthusiastic educator are likely to acquire the educator’s outlook concerning interest, motivation, and beliefs, leading to enhanced knowledge and a positive attitude toward education ( Keller et al., 2016 ). Developing excitement and enjoyment in teaching and the subject area should be a central element of educators’ training. Additionally, an atmosphere that allows educators to maintain enthusiasm is necessary during their daily work. For example, educators can avoid stressful working conditions by reducing organizational workloads and management responsibilities. Finally, it may be possible to maximize learners’ interest, motivation, and achievement by enhancing educators’ enthusiasm. Throughout the course, letting the learners speak and share their perspectives, engaging, giving advice regarding the accuracy or errors of their statements, and addressing their mistakes are factors that contribute to the enthusiasm of the teacher that leads to students’ achievement. To include the perspectives of other professionals in the field of education, it would be useful to conduct further research on the topic of teacher enthusiasm. Studies involving educators with different levels of knowledge, rather than just new educators, could help to evaluate enthusiasm levels. Additionally, investigators can conduct studies on a national and international basis, regardless of their academic background.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Ainley, M., and Hidi, S. (2014). “Interest and enjoyment,” in International Handbook of Emotions in Education. eds. R. Pekrun and L. L. Garcia (New York, NY: Routledge), 205–227.

Google Scholar

Baloch, K., and Akram, M. W. (2018). Effect of teacher role, teacher enthusiasm and entrepreneur motivation on startup, mediating role technology. Arabian J. Bus. Manag. Rev. 7, 1–14. doi: 10.12816/0052284

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Bedir, H., and Yıldırım, Ö. G. R. (2000). Teachers’ enthusiasm in ELT classes: views of both students and teachers. Çukurova Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Dergisi 6, 119–130.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (ed.) (2014). “Society, culture, and person: a systems view of creativity,” in The Systems Model of Creativity (Dordrecht: Springer), 47–61.

Csikszentmihalyi, M., and Seligman, M. (2000). Positive psychology. Am. Psychol. 55, 5–14. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.5

Derakhshan, A. (2021). The predictability of Turkman students’ academic engagement through Persian language teachers’ nonverbal immediacy and credibility. J. Teach. Persian Speak. Other Lang. 10, 3–26. doi: 10.30479/jtpsol.2021.14654.1506

Derakhshan, A., Kruk, M., Mehdizadeh, M., and Pawlak, M. (2021). Boredom in online classes in the Iranian EFL context: sources and solutions. System 101, 102–556. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2021.102556

Dewaele, J. M., and Alfawzan, M. (2018). Does the effect of enjoyment outweigh that of anxiety in foreign language performance? Stud. Sec. Lang. Learn. Teach. 8, 21–45. doi: 10.14746/ssllt.2018.8.1.2

Dewaele, J. M., Chen, X., Padilla, A. M., and Lake, J. (2019). The flowering of positive psychology in foreign language teaching and acquisition research. Front. Psychol. 10:2128. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02128

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Dewaele, J. M., and Dewaele, L. (2017). The dynamic interactions in foreign language classroom anxiety and foreign language enjoyment of pupils aged 12 to 18. A pseudo-longitudinal investigation. J. Eur. Sec. Lang. Assoc. 1, 12–22. doi: 10.22599/jesla.6

Dewaele, J. M., and Li, C. (2021). Teacher enthusiasm and students’ social-behavioral learning engagement: the mediating role of student enjoyment and boredom in Chinese EFL classes. Lang. Teach. Res. 25:13621688211014538. doi: 10.1177/13621688211014538

Dewaele, J. M., and MacIntyre, P. D. (2014). The two faces of Janus? Anxiety and enjoyment in the foreign language classroom. Stud. Sec. Lang. Learn. Teach. 4, 237–274. doi: 10.14746/ssllt.2014.4.2.5

Dewaele, J. M., and MacIntyre, P. D. (2016). “Foreign language enjoyment and anxiety: the right and left feet of the language learner,” in Positive Psychology in SLA. eds. T. Gregersen, P. D. MacIntyre, and S. Mercer (Bristol: Multilingual Matters), 215–236.

Dewaele, J. M., MacIntyre, P. D., Boudreau, C., and Dewaele, L. (2016). Do girls have all the fun? Anxiety and enjoyment in the foreign language classroom. Theor. Pract. Sec. Lang. Acquisit. 2, 41–63.

Dewaele, J. M., Witney, J., Saito, K., and Dewaele, L. (2018). Foreign language enjoyment and anxiety in the FL classroom: the effect of teacher and learner variables. Lang. Teach. Res. 22, 676–697. doi: 10.1177/1362168817692161

Ford, B. Q., Feinberg, M., Lam, P., Mauss, I. B., and John, O. P. (2019). Using reappraisal to regulate negative emotion after the 2016 US presidential election: does emotion regulation trump political action? J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 117, 998–1015. doi: 10.1037/pspp0000200

Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: the broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. Am. Psychol. 56, 218–226. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.218

Fredrickson, B. L. (2003). The value of positive emotions. Am. Sci. 91, 330–335. doi: 10.1511/2003.4.330

Fredrickson, B. L. (2004). “Gratitude, like other positive emotions, broadens and builds,” in The Psychology of Gratitude. ed. R. A. Emmons and M. E. McCullough (New York: Oxford University Press), 145–166.

Frenzel, A. C., Becker-Kurz, B., Pekrun, R., Goetz, T., and Lüdtke, O. (2018). Emotion transmission in the classroom revisited: a reciprocal effects model of teacher and student enjoyment. J. Educ. Psychol. 110, 628–639. doi: 10.1037/edu0000228

Frenzel, A. C., Goetz, T., Lüdtke, O., Pekrun, R., and Sutton, R. E. (2009). Emotional transmission in the classroom: exploring the relationship between teacher and student enjoyment. J. Educ. Psychol. 101, 705–716. doi: 10.1037/a0014695

Hadie, S. N. H., Hassan, A., Talip, S. B., and Yusoff, M. S. B. (2019). The teacher behavior inventory: validation of teacher behavior in an interactive lecture environment. Teach. Dev. 23, 36–49. doi: 10.1080/13664530.2018.1464504

Hagenauer, G., and Hascher, T. (2014). Early adolescents’ enjoyment experienced in learning situations at school and its relation to student achievement. J. Educ. Train. Stud. 2, 20–30. doi: 10.11114/jets.v2i2.254

Han, Y., and Wang, Y. (2021). Investigating the correlation among Chinese EFL teachers’ self-efficacy, reflection, and work engagement[J]. Front. Psychol. 12:763234. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.763234

Jin, Y., and Zhang, L. J. (2018). The dimensions of foreign language classroom enjoyment and their effect on foreign language achievement. Int. J. Biling. Educ. Biling. 24, 1–15. doi: 10.1080/13670050.2018.1526253

Jin, Y., and Zhang, L. J. (2019). A comparative study of two scales for foreign language classroom enjoyment. Percept. Mot. Skills 126, 1024–1041. doi: 10.1177/0031512519864471

Joe, A. I., Kpolovie, P. J., Osonwa, K. E., and Iderima, C. E. (2014). Modes of admission and academic performance in Nigerian universities. Merit Res. J. Educ. Rev. 2, 203–230.

Jones, G. A. (2013). Governing quality: positioning student learning as a core objective of institutional and system-level governance. Int. J. Chinese Educ. 2, 189–203. doi: 10.1163/22125868-12340020

Keller, M. M., Becker, E. S., Frenzel, A. C., and Taxer, J. L. (2018). When teacher enthusiasm is authentic or inauthentic: lesson profiles of teacher enthusiasm and relations to students’ emotions. Aera Open 4, 1–16. doi: 10.1177/2332858418782967

Keller, M. M., Goetz, T., Becker, E. S., Morger, V., and Hensley, L. (2014). Feeling and showing: a new conceptualization of dispositional teacher enthusiasm and its relation to students' interest. Learn. Instr. 33, 29–38. doi: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2014.03.001

Keller, M. M., Hoy, A. W., Goetz, T., and Frenzel, A. C. (2016). Teacher enthusiasm: reviewing and redefining a complex construct. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 28, 743–769. doi: 10.1007/s10648-015-9354-y

Khajavy, G. H., MacIntyre, P. D., and Barabadi, E. (2018). Role of the emotions and classroom environment in willingness to communicate: applying doubly latent multilevel analysis in second language acquisition research. Stud. Sec. Lang. Acquisit. 40, 605–624. doi: 10.1080/00220970009600093

König, L., and Jucks, R. (2019). Influence of enthusiastic language on the credibility of health information and the trustworthiness of science communicators: insights from a between-subject web-based experiment. Interact. J. Med. Res. 8:e13619. doi: 10.2196/13619

Kruk, M., and Zawodniak, J. (2018). “Boredom in practical English language classes: insights from interview data,” in Interdisciplinary Views on the English Language, Literature and Culture. eds. L. Szymanski, J. Zawodniak, A. Łobodziec, and M. Smoluk (Uniwersytet Zielonogorski: Zielona Gora), 177–191.

Kunter, M., Frenzel, A., Nagy, G., Baumert, J., and Pekrun, R. (2011). Teacher enthusiasm: dimensionality and context specificity. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 36, 289–301. doi: 10.1016/j.cedpsych.2011.07.001

Kunter, M., and Holzberger, D. (2014). “Loving teaching: research on teachers’ intrinsic orientations,” in Teacher Motivation. eds. P. W. Richardson, S. A. Karabenick, and H. M. G. Watt (New York, NY: Routledge), 105–121.

Kunter, M., Klusmann, U., Baumert, J., Richter, D., Voss, T., and Hachfeld, A. (2013). Professional competence of teachers: effects on instructional quality and student development. J. Educ. Psychol. 105, 805–820. doi: 10.1037/a0032583

Lazarides, R., Gaspard, H., and Dicke, A. L. (2019). Dynamics of classroom motivation: teacher enthusiasm and the development of math interest and teacher support. Learn. Instr. 60, 126–137. doi: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2018.01.012

Li, C. (2020). A positive psychology perspective on Chinese EFL students’ trait emotional intelligence, foreign language enjoyment and EFL learning achievement. J. Multiling. Multicult. Dev. 41, 246–263. doi: 10.1080/01434632.2019.1614187

Li, C., Jiang, G., and Dewaele, J. M. (2018). Understanding Chinese high school students’ foreign language enjoyment: validation of the Chinese version of the foreign language enjoyment scale. System 76, 183–196. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2018.06.004

MacIntyre, P. D. (2016). “So far so good: an overview of positive psychology and its contributions to SLA,” in Positive Psychology Perspectives on Foreign Language Learning and Teaching. eds. D. Gabrys-Barker and D. Gałajda (Cham: Springer), 3–20.

MacIntyre, P., and Gregersen, T. (2012). Emotions that facilitate language learning: the positive-broadening power of the imagination. Stud. Sec. Lang. Learn. Teach. 2, 193–213. doi: 10.14746/ssllt.2012.2.2.4

MacIntyre, P. D., Gregersen, T., and Mercer, S. (2019). Setting an agenda for positive psychology in SLA: theory, practice, and research. Mod. Lang. J. 103, 262–274. doi: 10.1111/modl.12544

MacIntyre, P. D., and Vincze, L. (2017). Positive and negative emotions underlie motivation for L2 learning. Stud. Sec. Lang. Learn. Teach. 7, 61–88. doi: 10.14746/ssllt.2017.7.1.4

Mierzwa, E. (2019). Foreign language learning and teaching enjoyment: teachers’ perspectives. J. Educ. Cult. Soc. 10, 170–188. doi: 10.15503/jecs20192.170.188

Nur, A. (2019). The influential factors on students’ enthusiasm in learning speaking skills. English Lang. Teach. ELF Learn. 1, 24–38. doi: 10.24252/elties.v1i1.7420

Nurhasanah, S., and Sobandi, A. (2016). Learning interest as determinant student learning outcomes. J. Pend. Manaj. Perk. 1, 128–135. doi: 10.17509/jpm.v1i1.3264

O’Donnell, R. J., and White, G. P. (2005). Within the accountability era: principals’ instructional leadership behaviors and student achievement. NASSP Bull. 89, 56–71. doi: 10.1177/019263650508964505

Ostafin, B. D., Brooks, J. J., and Laitem, M. (2014). Affective reactivity mediates and inverse relation between mindfulness and anxiety. Mindfulness 5, 520–528. doi: 10.1007/s12671-013-0206-x

Oxford, R. (2015). Emotion as the amplifier and the primary motive: some theories of emotion with relevance to language learning. Stud. Sec. Lang. Learn. Teach. 3, 371–393. doi: 10.14746/ssllt.2015.5.3.2

Patrick, B. C., Hisley, J., and Kempler, T. (2000). What’s everybody so excited about? The effects of teacher enthusiasm on student intrinsic motivation and vitality. J. Exp. Educ. 68, 217–236. doi: 10.1080/00220970009600093

Pavelescu, L. M., and Petric, B. (2018). Love and enjoyment in context: four case studies of adolescent EFL learners. Stud. Sec. Lang. Learn. Teach. 8, 73–101. doi: 10.14746/ssllt.2018.8.1.4

Pavlenko, A. (2013). “The affective turn in SLA: from affective factors to language desire and com-modification of affect,” in The Affective Dimension in Second Language Acquisition. eds. D. Gabrys-Barker and J. Bielska (Bristol: UK Multilingual Matters), 3–28.

Pekrun, R. (2006). The control-value theory of achievement emotions: assumptions, corollaries, and implications for educational research and practice. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 18, 315–341. doi: 10.1007/s10648-006-9029-9

Pekrun, R., Frenzel, A. C., and Goetz, T. (2007). “The control-value theory of achievement emotions: an integrative approach to emotions in education,” in Emotion in Education. eds. P. Schultz and R. Pekrun (Amsterdam: Academic Press), 13–36.

Pekrun, R., and Perry, P. (2014). “Control-value theory of achievement emotions,” in International Handbook of Emotions in Education. eds. R. Pekrun and L. Linnenbrink-Garcia (New York, NY: Routledge), 120–141.

Piniel, K., and Albert, Á. (2018). Advanced learners’ foreign language-related emotions across the four skills. Stud. Sec. Lang. Learn. Teach. 8, 127–147. doi: 10.14746/ssllt.2018.8.1.6

Pithers, B., and Holland, T. (2006). “Student expectations and the effect of experience.” in Australian Association for Research in Education Conference ; May 2021; Adelaide, Australia.

Prior, M. (2019). Elephants in the room: an affective turn, or just feeling our way? Mod. Lang. J. 103, 516–527. doi: 10.1111/modl.12573

Ruzek, E. A., Hafen, C. A., Allen, J. P., Gregory, A., Mikami, A. Y., and Pianta, R. C. (2016). How teacher emotional support motivates students: the mediating roles of perceived peer relatedness, autonomy support, and competence. Learn. Instr. 42, 95–103. doi: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2016.01.004

Setianingsih, T., and Nafisah, B. Z. (2021). Memory trick game towards students’ enthusiasm in learning grammar. J. Ilmu Sos. Pend. 5, 323–328. doi: 10.36312/jisip.v5i3.2143

Shao, K., Pekrun, R., and Nicholson, L. J. (2019). Emotions in classroom language learning: what can we learn from achievement emotion research? System 86, 102–121. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2019.102121

Shirvan, M. E., and Talebzadeh, N. (2018). Exploring the fluctuations of foreign language enjoyment in conversation: an idiodynamic perspective. J. Intercult. Commun. Res. 47, 21–37. doi: 10.1080/17475759.2017.1400458

Talebzadeh, N., Shirvan, M. E., and Khajavy, G. H. (2020). Dynamics and mechanisms of foreign language enjoyment contagion. Innov. Lang. Learn. Teach. 14, 399–420. doi: 10.1080/17501229.2019.1614184

Villavicencio, F. T., and Bernardo, A. B. (2013). Positive academic emotions moderate the relationship between self-regulation and academic achievement. Br. J. Educ. Psychol. 83, 329–340. doi: 10.1111/j.2044-8279.2012.02064.x

Wang, Y. L., and Derakhshan, A. (2021). Review of the book: investigating dynamic relationships among individual difference variables in learning English as a foreign language in a virtual world, by M. Kruk. System 102531. doi: 10.1016/j.system.2021.102531

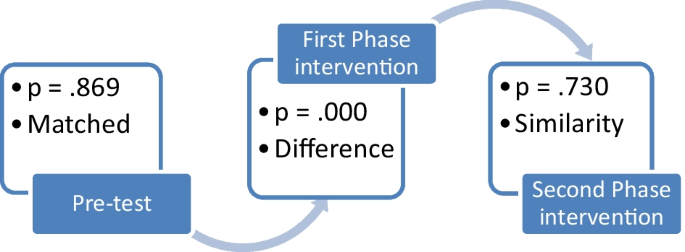

Wang, Y. L., Derakhshan, A., and Zhang, L. J. (2021). Researching and practicing positive psychology in second/foreign language learning and teaching: the past, current status and future directions. Front. Psychol. 12:731721. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.731721