Why the Short-Lived Pony Express Still Fascinates Us

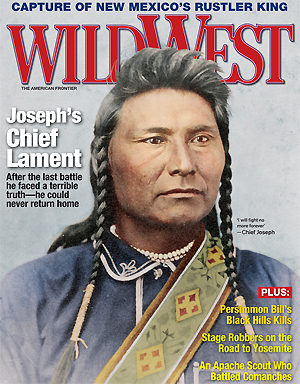

The Pony Express operated for less than two years, but its legend—burnished by Buffalo Bill Cody—lives on.

In its day, the Pony Express was like the Twitter or Facebook of the mid-1800s: a means of communication that could move information across the North American continent faster than ever before, though it was powered by horses .

Almost no records survived, though, so the history of the Pony Express is littered with impostors, inaccuracies, and plain bunkum . In West Like Lightning , author Jim DeFelice separates the facts from the fiction.

When National Geographic caught up with him at his home in Warwick, New York, DeFelice explained how the Pony Express came to embody rugged American virtues as much as rodeos or westerns; how Buffalo Bill Cody was its greatest promoter, though he never actually rode for the company; and why, if things had turned out differently, we would be using Pony Express cards, not American Express.

I was amazed to discover that the Pony Express existed for just 18 months and made less than 400 runs. Yet the legend has lived on. Why do you think that is?

I was kind of blown away when I first found that out myself! There are many factors, but the most important reason is because there’s so much embodied in the story of the Pony Express that’s part of the American spirit: man verses nature , rugged individual exploits. And you also have these famous personalities intersecting with it, from Buffalo Bill Cody to Mark Twain .

It was also happening at a really important time in American history, right on the cusp of the Civil War. It’s the tail end of the Gold Rush and there are all of these cool inventions, like the telegraph and railroads. Above all, it was the riders’ endurance and resilience that made the Pony Express live on, and still resonate today.

You follow one particularly momentous bit of news westward. Set the scene for us and tease out the parallels with today’s Internet.

The book is set a day or two after Abraham Lincoln’s election and the Pony Express is bringing news of what happened in the election to the West, not only to Sacramento, San Francisco, and the rest of California, but also to communities along the way. Just four years before it had taken months for the news to get there, but the Pony Express company set up knowing that this was a huge, momentous event. They added extra relay stations and made a lot of use of the telegraph and were able to deliver the message in a matter of days.

For Hungry Minds

Everybody back East knew that this was a huge election that very possibly was going to lead to war, and it was the kind of information that had to get out and be spread. The newspapers of the day had a symbiotic relationship with the Pony Express. They would get specific dispatches, almost what we would call a Facebook post today, and take that information, plop it on their front page and say, “Just Fresh in From the Pony Express…” The messages had to be light and small, so in another way they were like Twitter. For the election, they were so excited they wrote the news on the outside of the envelopes, so everyone would know right away what had happened.

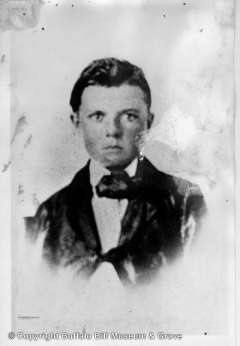

Much of the history of the Pony Express was lost with its records. As a result there were many “liars of the purple sage,” the most notorious being Buffalo Bill Cody. He never actually rode with the Express, yet he more than anyone made it famous. Unpack that paradox.

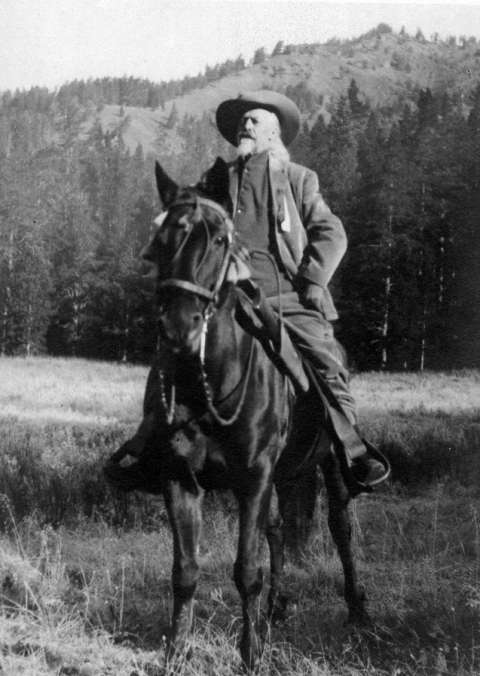

Bill Cody is by far the most important rider of the Pony Express, but he never actually did ride for them. [laughs] A lot of ink has been spilled on both sides of the argument, but it’s clear from the evidence that he was just too young to have ridden in the Pony Express. On the other hand, what he did afterwards with his Wild West Shows catapulted the Pony Express into the public imagination. The Pony Express was almost always included as either an opening act or a finale.

The Wild West Show was like the Super Bowl coming to your town and it went not only all over America, but also to Europe, most notably, London. The Pony Express vignette had about as much to do with reality as motorcycles would have had to do with the Pony Express then. But it raised public awareness.

What sort of men actually did ride the Pony Express? Was there a particular type? And what sort of equipment did they have?

As a general rule, they were young men, usually late teens on up to early 20s. They were lightweight even for the time; sinewy and of course really good riders. To ride 100 miles, potentially four times a week, in all kinds of weather, day and night, you have to be a top rider with a lot of endurance. Some riders lasted a couple of rides and would leave.

There were quite strict rules for the riders. Two of the most important were that they were not allowed to drink alcohol, and that they were forbidden from using curse words. But there’s all sorts of tales about a lot of bad words and drinking heavily. [laughs]

The Pony Express was established by a man called William H. Russell. What sort of a man was he? And why did he create it?

Russell is a fascinating character. He’s a 19 th -century visionary showman entrepreneur, who goes to the dark side toward the end of his career. His vision was to create an empire transporting goods, people, and information everywhere west of the Missouri River to California. They had elements of that empire in place even before they started the Pony Express. They had a freight business where they delivered all sorts of goods, mostly for the U.S. Army, which was their biggest customer. They had a stagecoach business, a bank, and an insurance company. It sounds like an improbable idea, but a company had done that same thing barely a few decades before, starting in upstate New York, and it’s still with us today. It’s called the American Express. If the Pony Express had succeeded, we wouldn’t be leaving home without the Pony Express today instead of American Express. [laughs]

The hardest part of the trail was through the Sierra Nevada. Give us a picture of the challenges the riders faced there and elsewhere.

The hardest part of the Sierra Nevada would have been in winter. There would be snow drifts and the tracks are relatively narrow. You could fit a horse, sometimes two horses, but if there was a wagon in front of you, you had to wait until you got to a spot where you could get around it. In some places you’re up very high, with sheer cliffs below you, like the area where the Donner Party had succumbed a few years earlier.

You May Also Like

The legend of Area 51—and why it still fascinates us

Who were the original 49ers? The true story of the California Gold Rush

Who was the real Calamity Jane? Historians search for an answer.

The desert was also very dangerous. If you knew where the path was, you were fine. In most places it was relatively well marked. But west of Salt Lake, in the desert, if you went off course a bit you could suddenly find yourself in a lot of trouble. There’s a story of at least one rider, who knew the trail very well, but was trying to take a short cut one night and ended up in quicksand and only survived by luck.

In the far West, relations with Native Americans were complex and sometimes violent, but some riders spanned both worlds. Tell us about Nick Wilson, “The White Indian.”

Nick Wilson is an interesting character. One caveat is that he’s so colorful, and there are so many different tales attached to him, that to be definitive is very difficult! Uncle Nick , as he was called in later life, was from a Mormon family, who as a young boy then went to live with a Shoshone Indian family in the Utah area. He then ends up as a teenager coming back home where he meets someone who is recruiting for the Pony Express, and he gets a job. Obviously he’d be a good rider if he could ride with the Pony Express. He also worked as a stagecoach driver and a trapper. He was also said to have had a good way with breaking horses, like a horse whisperer.

Relations between whites and Native Americans broke down completely with the Pyramid Lake War. Describe its origins and what effects it had on the Pony Express.

There’s some contention about what actually happened, but the Pyramid Lake War , or Paiute War as it is also known, was up to that point the biggest conflict between Indian tribes and white settlers. It almost certainly started when some whites raped, or wanted to rape, some Indian girls. Naturally, their families took exception and the end result was that a number of whites were killed and several Pony Express stations were burned down. As a result, the service was stopped because it was too dangerous to proceed.

Remarkably, the people of eastern California, who were served by the Pony Express, raised money to rebuild some of the stations and supplied volunteers to help. The work force went from West to East, rebuilding the stations, and the service got back up and running shortly thereafter. Interestingly, that happened while there was a census being taken. Because of that, riders who were part of the work force to rebuild the stations are recorded at certain locations where the census was taking place. That enabled me to see how they are being listed in the census and get a picture of their ages and work conditions.

Why did the Pony Express end? And is it today anything more than a colorful footnote in the history of the American West?

The Pony Express lives on because it’s that story of the American spirit, of individuals against nature, of endurance, and speed . It continues to resonate because for the most part it’s a very positive image. It’s a Western with only good guys, as long as you ignore the Indian War. And because of that, people can relate to it.

But the Pony Express was always intended as a short-term venture to raise public awareness—like a huge PR stunt—to get a big mail contract. When it came to the mail contract, sadly, then just as today, when you rely on Congress, you may find that at the end of the day that they’re not going to come through for you. That’s what happened with the Pony Express. The mail contract they were counting on came much too late to help them, and when it did come, it was far too small.

But it is financial stuff that sinks Russell. He is so desperate for money that he goes to the War Department and tries to get an advance on some other contracts they had. He doesn’t succeed, but ends up with bonds that are supposed to be in trust. They don’t belong to the government; they belong to the Indian tribes. But Russell uses them as collateral to get cash advances. Unfortunately, the whole scheme quickly collapsed. He was arrested, hauled before Congress and the judge, but for various reasons the whole matter gets dropped because then, as now, Congress doesn’t like to air its dirty laundry in public. Not only did that ignobly end the Pony Express, it also ended Russell’s career as an entrepreneur.

This interview was edited for length and clarity.

Simon Worrall curates Book Talk . Follow him on Twitter or at simonworrallauthor.com .

Related Topics

- HISTORY AND CIVILIZATION

- HISTORIC SITES

- MODERN HISTORY

The incredible details 'Masters of the Air' gets right about WWII

MLK and Malcolm X only met once. Here’s the story behind an iconic image.

The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?

What was Leonard Bernstein and JFK's friendship really like?

The short, sweet, and sticky history of jam

- Environment

History & Culture

- History & Culture

- History Magazine

- Gory Details

- Mind, Body, Wonder

- Paid Content

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

MA in American History : Apply now and enroll in graduate courses with top historians this summer!

- AP US History Study Guide

- History U: Courses for High School Students

- History School: Summer Enrichment

- Lesson Plans

- Classroom Resources

- Spotlights on Primary Sources

- Professional Development (Academic Year)

- Professional Development (Summer)

- Book Breaks

- Inside the Vault

- Self-Paced Courses

- Browse All Resources

- Search by Issue

- Search by Essay

- Become a Member (Free)

- Monthly Offer (Free for Members)

- Program Information

- Scholarships and Financial Aid

- Applying and Enrolling

- Eligibility (In-Person)

- EduHam Online

- Hamilton Cast Read Alongs

- Official Website

- Press Coverage

- Veterans Legacy Program

- The Declaration at 250

- Black Lives in the Founding Era

- Celebrating American Historical Holidays

- Browse All Programs

- Donate Items to the Collection

- Search Our Catalog

- Research Guides

- Rights and Reproductions

- See Our Documents on Display

- Bring an Exhibition to Your Organization

- Interactive Exhibitions Online

- About the Transcription Program

- Civil War Letters

- Founding Era Newspapers

- College Fellowships in American History

- Scholarly Fellowship Program

- Richard Gilder History Prize

- David McCullough Essay Prize

- Affiliate School Scholarships

- Nominate a Teacher

- Eligibility

- State Winners

- National Winners

- Gilder Lehrman Lincoln Prize

- Gilder Lehrman Military History Prize

- George Washington Prize

- Frederick Douglass Book Prize

- Our Mission and History

- Annual Report

- Contact Information

- Student Advisory Council

- Teacher Advisory Council

- Board of Trustees

- Remembering Richard Gilder

- President's Council

- Scholarly Advisory Board

- Internships

- Our Partners

- Press Releases

History Resources

The Pony Express: The Fastest Delivery of a Message across America

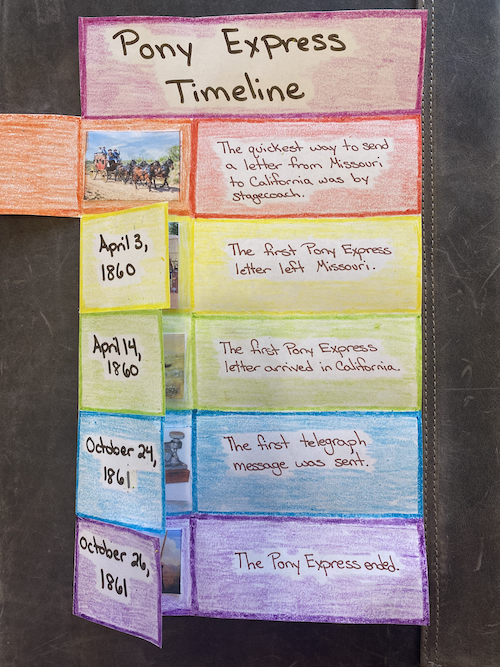

The inauguration of a new service, the Pony Express, on April 3, 1860, promised the fastest communication ever from the Missouri River to California. How long did a Pony Express message take to go from its starting point in St. Joseph, Missouri to Sacramento, California? How many years was the Pony Express in existence? How many riders were employed? What hardships did the riders experience? Finding the answers to these questions and many more like them captivates youngsters, encouraging them to read about, imagine, and romanticize an era of long ago. Pre-Civil War settlers who had already reached California and its promise of gold found themselves cut off from the rest of the world. Butterfield Express was an overland mail route via stagecoach that took twenty-three days for delivery. Most people knew it was a matter of time before the telegraph and railroad would span the continent, but with the Civil War looming in the near future, something was needed now to replace the existing overland route. Elementary students can examine primary documents such as newspaper articles, stories, and letters to understand how important the Pony Express was for settlers seeking east-to-west communication in record time.

Essential Question

Why was the Pony Express described as an immediate success by Western settlers but a financial failure for its proprietors?

Motivation

- Explain that advertisements were used in the 1860s to influence people to demand better and faster methods of communication.

- Ask how people communicate today.

- Students will analyze newspaper articles, stories, and letters to understand the significance of the Pony Express.

- Students will create a poster or a power-point presentation based on their research.

- Advertisement for Pony Express, 1860 , National Postial Museum

- "MEN WANTED!" Poster created by William Finney , Legends of America (scroll down on page)

- "Here is the Story of the Pony Express as published in the Newspapers of 1860-1861." , National Pony Express Association

- Pony Express Riders (PDF)

- "Pony Express Stations."

- "Life on the Pony Express," Story of George S. Stiers. Taken from County Home Tarrant Co., Texas , Library of Congress

- Pony Express Facts , National Pony Express Association

- Story of the Pony Express , City of St. Joseph, Missouri

- "When the Pony Express was in Vogue." Taken from San News Letter, September 1925 , San Francisco Museum

- Blank poster boards

- Distribute to the students copies of the "MEN WANTED!" poster and the St. Joseph newspaper advertisement.

- Explain that the purpose of the advertisement was to draw public attention to the Central Route in order to gain a government mail contract for the Central Overland California and Pikes Peak Express Company. The demand was to speed communication from the East to West.

- Discuss the appeal the advertisement and poster had to the public.

- Divide students into groups of four and assign each group one topic listed below. Distribute copies of all primary documents to each group for analyzation and ask students to prepare presentations for Day Two that address their topic’s questions.

Topic A: Historical Background

- Who founded the Pony Express and when was it established?

- Why was the Pony Express established?

- What investments did the proprietors make to get the Pony Express in operation?

Topic B: The Riders

- List three of the earliest riders.

- What was their base salary?

- What were their qualifications?

- What was the average speed of a rider, and how often did a rider change?

Topic C: The Horse

- What type of horse was purchased and why?

- How often were the horses changed?

- Describe, explain, and provide a picture of the mochila (saddlebag).

Topic D: The Station Provide a brief overview of the following:

- general physical conditions of the structure

- sleeping arrangements

- food served at the stations

- hospitality of station masters

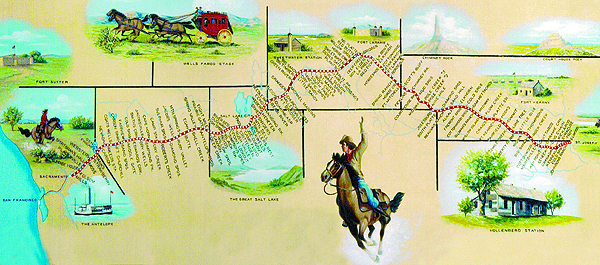

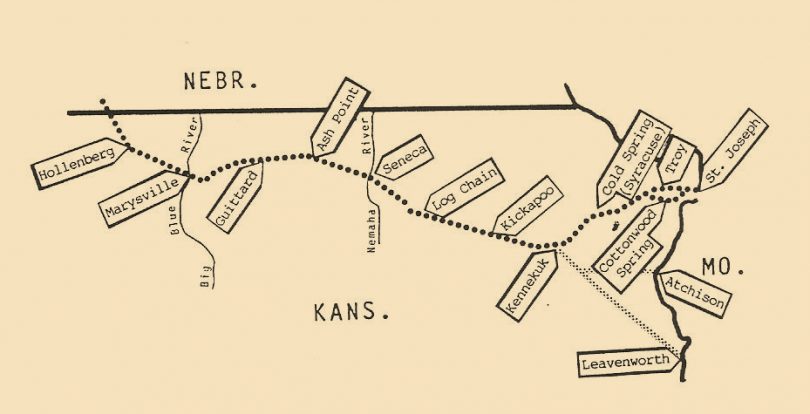

Topic E: The Route

- Use a map to point out the states that encompassed the 1,966 miles of the Pony Express.

- List the hardships the rider experienced along the route.

Topic F: Termination of the Pony Express

- When did the Pony Express end?

- Discuss the new method of technology that brought an end to the Pony Express and explain why it was used.

DOWNLOAD LESSON CHARTS 1&2 (PDF DOCUMENT) --> DOWNLOAD LESSON CHARTS 1&2 (PDF DOCUMENT) -->

In groups, the students will create a poster (or a power point-presentation) that will focus on the specific topics they were assigned on Day One and that will respond to the questions. The students will explain their posters or power-point presentations to the entire class.

Closure/Discussion

The teacher will lead a discussion of the successes and failures of the Pony Express and will write key points that emerge from the class discussion on the board.

Application

Students will make a timeline showing the progression of technology for communication from the days of the Pony Express to the present. They will write a paragraph explaining the advantages of the most modern forms of communication.

Suggested Books

- Adams, Samuel Hopkins. The Pony Express . Chicago: Spencer Press, Inc., 1950.

- Bailey, W.F. "The Pony Express." Golden West: True Stories of the Old West .

- Freeport, NY: Maverick Publications, Inc., Vol.1, No. 1, 1964.

- Banning, Captain William, and George Hugh Banning. Six Horses . New York: Century Company, 1930.

- Barrett, Ivan J. Eph Hanks -- Fearless Mormon Scout . American Fork, UT: Covenant Communications, Inc., 1990.

- Beck, Warren A, and Ynez D. Haase. Historical Atlas of the American West . Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1992.

- Benson, Joe. Traveller’s Guide to the Pony Express Trail . Falcon Press, 1995.

- Biggs, Donald. "The Pony Express: Creation of a Legend." San Francisco: privately printed document, 1956.

- Bloss, Roy S. Pony Express: The Great Gamble . Berkeley: Howell-North, 1959.

- Corbet, Christopher. Orphans Preferred: The Twisted Truth and Lasting Legend of the Pony Express . New York: Broadway Books, 2003.

- Di Certo, Joseph. The Saga of the Pony Express . Missoula, MT: Mountain Press Publishing Company, 2002.

- Settle, Raymond W., and Mary Lund Settle. The Story of the Pony Express . London: W. Foulsham & Co. Ltd., 1955.

Stay up to date, and subscribe to our quarterly newsletter.

Learn how the Institute impacts history education through our work guiding teachers, energizing students, and supporting research.

- Topical Reference Pages

- Pony Express

- The Story Of The Pony Express

The Story of the Pony Express

By Nancy Pope

Volume 1, Issue 2 April–June 1992

The Pony Express is one of the most colorful episodes in American history, one which can be used to measure not only the growth of the nation, but the pioneering spirit of our predecessors. The name "Pony Express" evokes images of courageous young men crossing long stretches of country, frequently under harsh conditions, facing the constant threat of death. And, like so many legendary events of the "Old West," there have been wild exaggerations of the facts.

Despite the braggadocio, these young horsemen faced numerous dangers, such as thieves, deserts, or blizzards. Riders continued even at night when the only illumination came from the moon or flashes of lightning.

The Pony Express grew out of a need for swifter mail service between the East and West prior to the Civil War. After gold was discovered in 1848 in Sutter's Mill in California, prospectors joined with homesteaders flocking westward. That same year, the Post Office Department awarded a contract to the Pacific Mail Steamship Company to carry mail to California. Under the terms of the contract, the mail was carried by ship from New York to Panama, where it was taken across the Isthmus of Panama by horseback or rail, and then put aboard ships bound for San Francisco. Under the best of conditions, a letter could be carried to the West Coast in three or four weeks. But, that schedule was optimistic.

As the tensions of the approaching Civil War grew, the division between northern and southern states widened, exacerbating the problems of mail service to the western states. Both the North and the South desired California's vast resources. By 1860, almost 1/2 million people were living in the western states. Those people were determined to have the delivery time of their mail improved.

The completion of a coast-to-coast railroad was years away. At that time, the railroads extended only as far west as the Mississippi River. The completion of a telegraph linking both coasts was close to becoming a reality, but it would still be more than a year before it could be completed.

Some mail also was hauled by stagecoach across country, beginning on September 15, 1858, when the Post Office Department issued a contract to the Overland Mail Company, operated by John Butterfield. Butterfield's stages used the 2,795-mile "Southern Route" between Tipton, Missouri, and San Francisco. Although the advertised traveling time was 24 days, as a practical matter cross-country stagecoach mail service was often delayed for months. Such delays were keenly felt by Californians. The citizens of Los Angeles, for example, learned that California had been admitted to the Union fully six weeks after the fact.

Senator William M. Gwin of California was among those who saw the need to improve the timeliness of mail service to the West. Traveling from San Francisco to Washington, D.C., he was aware of the truth behind one of the jokes of the period—that the terms of the western members of Congress might expire before they even reached the District of Columbia.

Expecting the Confederacy to cut off the only land-based source of communication between the Federal Government and California, Gwin persuaded Congress to consider the approval of an alternate route. This route would be about 800 miles shorter and was known as the "Central Route."

Gwin found the answer to his concerns in William Russell, a stage express company owner. Russell agreed to establish a speedy and reliable express service over the Central Route, stretching from St. Joseph, Missouri to San Francisco. Russell hoped to prove that his company was an able competitor to John Butterfield's Overland Mail Company, and win away the exclusive government mail contract.

Russell, and his partners, Alexander Majors and William Waddell, were expected to operate the Pony Express for about a year. Once the race to connect the telegraph had ended, with both ends expected to meet at Salt Lake City, the Pony Express would no longer be needed.

Although both Russell and Gwin are referred to as the "Father of the Pony Express," the actual responsibility for making the venture work fell to Alexander Majors. Although he and Waddell had initially opposed the project, once his firm was pledged to the Pony Express, Majors committed his energies to the project's success.

With precision and expertise which would be envied by any military tactician, Alexander Majors arranged for the purchase of over 400 ponies; the building of 200 stations in desolate, uninhabited areas; the hiring of station masters to staff them; the stocking of provisions; and, of course, the hiring of the riders themselves. Majors' task, difficult under the best circumstances, had to be completed in two months.

Relay stations were placed 10 miles apart. Every third station was a home station, where extra ponies, firearms, men, and provisions were kept. Here, the mail would be handed over to a new rider.

The route form St. Joseph to San Francisco stretched over 1,966 miles, through the plains of Kansas and into Nebraska, along the valley of the Platte River, across the Great Plateau, through the Rockies, into the valley of the Great Salt Lake, through the alkali deserts of Nevada, then over the snow-covered Sierra Mountains and finally into the Sacramento Valley. The mail was carried between Sacramento and San Francisco by steamboat.

About 80 young men rode for the Pony Express. When he hired the riders, Alexander Majors gave each of them a Bible and required them to sign a pledge promising not to swear, drink alcohol, or fight with other employees. The riders carried the mail in the four pockets of a mochila which fit snugly over the saddle and was quickly switched from one horse to another. Letters were wrapped in oil silk to protect them from moisture. The price of a letter was $5 at first, and reduced to $1 per half-ounce by July 1, 1861. Weight was an important factor. Riders, horses, letters, and gear were all chosen with this in mind. The horses averaged about 14 1/2 hands high and weighed less than 900 pounds.

The arrival of the first rider into San Francisco was greeted with tumultuous excitement as the streets filled with people cheering the event. Even Jessie Benton Fremont, the widow of the famous western explorer John C. Fremont, was on hand to witness the rider's arrival shortly before midnight on April 13, 1860.

*EnRoute was the National Postal Museum's newsletter.

- Finding Guides

- Forensic Laboratory

- Maynard Sundman Lecture Series

- Symposia and Lectures

- Research Funding

- External Research Links

- The NPM Awards for Scholarship in Postal History

- Appointments to Research Objects

- Contact the Blount Research Chair

- School Field Trips

- Professional Development

- Curriculum Guides

- Classroom Resources

- Education Partners

- National History Day 2022-2023

- National History Day 2021-2022

- Oral History

- Research Articles

- Conversations About Philately

- Tools of the Hobby

- Introduction

- Apple Maps Guides

- e-Newsletter

- Hands-On Activities

- Downloadable Activities

- Just For Kids!

- Fun & Games

The most comprehensive and authoritative history site on the Internet.

Pony Express

Facts, information and articles about the pony express, an event of westward expansion from the wild west, pony express facts.

April 3, 1860 – October 24, 1861

2000 miles, between St. Joseph Missouri and Sacramento, California

William H. Russell, William B. Waddell, Alexander Majors

Pony Express Articles

Explore articles from the History Net archives about Pony Express

Pony Express summary: Three men in the mid-1800s had an idea to open up a mail delivery system that reached from the Midwest all the way to California. The lack of speedy communication between the mid-west and the west was accentuated by the looming threat of a civil war. Russell, Waddell and Majors designed a system that spanned a number of over one hundred stations, each approximately two hundred forty miles long, across the country.

The Pony Express employed about eighty deliverymen and had around four hundred to five hundred horses to carry these riders from one post to the next. Monthly pay for these riders was fifty dollars, which were good wages at the time. Although this method of carrying mail was dangerous and difficult, all save one delivery made it to their destination.

This new way of mail delivery carried mail between Missouri and California in the span between ten and thirteen days, an astonishing speed for the time. Nineteen months after launching the Pony Express, it was replaced by the Pacific Telegraph line. The Pony Express was no longer needed. While it existed, the Pony Express provided a needed service but it was never quite the financial success it was hoped to be. The founders of the Pony Express line found that they were bankrupt.

Even though the Pony Express Company was no longer operating, its logo lived on when Wells Fargo purchased it and used it from 1866 until 1890 in their freight and stagecoach company.

Articles Featuring Pony Express From History Net Magazines

Featured article, the pony express: riders of destiny.

Every spring the National Pony Express Association attempts a scrupulously authentic reenactment of the legendary cross-country mail ride linking St. Joe on the wide Missouri with the California state capital of Sacramento. But as no one is entirely sure exactly what happened on April 3, 1860 — or for the rest of the 78 or so weeks the Pony Express crossed the West — scrupulous authenticity is something of a problem. The run, of nearly 2,000 miles, is longer, its reenactors always stress, than the fabled Iditarod dog-sled race, but they don’t have to deal with Alaska’s cold. And they also avoid snow. Since there is still too much snow in much of the West at the beginning of April, the Pony re-rides are held in June.

The Pony Express was in business of one sort or another between April 3, 1860, and October 26, 1861. Purists like to tweak that ending date, noting that mailbags — called mochilas — were still in transit into November. But for all practical purposes ‘our little friend the Pony,’ as the Sacramento Bee called it, ran no more after the transcontinental telegraph was completed on October 24, 1861.

The story of the Pony Express is a bit like the story of Paul Revere’s ride — an actual historic event, rooted in fact and layered with centuries (a century and a half in the Pony’s case) of fabrications, embellishments and outright lies. In the mid-20th century, William Floyd, one of a legion of amateur historians to delve into the tale of the Pony Express, threw up his hands and observed, ‘It’s a tale of truth, half-truth and no truth at all.’ He was right on each account.

The business was called the Central Overland California and Pike’s Peak Express Company, a name too cumbersome to appear on anything. The company’s mail service across America in 1860 and 1861 became known as the Pony Express, a legend in its own time. Americans living on the Pacific slope in the newly minted state of California, drawn there by the Gold Rush, were desperate for news of home. The Pony Express dramatically filled that gap by promising to deliver mail across the country from the end of the telegraph in the East to the start of the telegraph in the West, in 10 days time or less. Normal mail, brought overland or via ship, took months. The term ‘pony express’ had been used before, and, indeed, Americans had transmitted information on the backs of fast horses since colonial times. Historians of mail service always note that Genghis Khan used mounted couriers.

It was from the first a madcap if wonderfully romantic idea. Well-mounted light fellows (Mark Twain called them ‘little bits of men, brimful of spirit’) would, by using a series of fresh horses and relief stations, cross wild and largely uninhabited expanses from Missouri to the far coast.

The firm that bankrolled the Pony — and the term bankrolled must be used very lightly, for the venture hemorrhaged money from day one — was Russell, Majors & Waddell. Household names in their heyday on the frontier, William Hepburn Russell, Alexander Majors and William Bradford Waddell had made their reputation hauling freight to military outposts. Their business may very well have been broke when the Pony Express started (the result of massive losses incurred freighting during the so-called Mormon War of the late 1850s), but no one appears to have known that. The firm’s reputation and the chutzpah of its primary spokesman, Russell, got things rolling.

The business — which originally intended to cross the west once a week, moving important mail on horseback — was not a financially sound venture. Russell, Majors & Waddell spent a great deal of money on horses and dozens of way stations, which were required every 10 to 15 miles depending on the terrain. They also had to hire riders and station tenders. East of Salt Lake City, the Pony Express appears to have piggybacked on existing overland stage operations, but west of the Mormon Jerusalem, things got a little dicey. It was expensive and complicated to operate such a venture. In many parts of the country, water had to be hauled considerable distances. And even at the initial rate of $5 a half ounce (later reduced), there was no way that a mochila , which held only 20 pounds of mail, could possibly carry enough correspondence to make this line pay. Its patrons were the government, newspapers, banks and businesses. The average person did not often send letters via Pony Express. We are dependent on notices that appeared in the California newspapers at the time announcing the arrival of the Pony and what mail it was carrying. Often the mochila contained only a couple of dozen letters. Considering how many riders and way station keepers had been involved in moving those letters from St. Joseph, Mo., the venture rates as one of the most fabled failed businesses in American history.

No sooner had the Pony Express begun than the Paiute War (or Pyramid Lake War) shut the line down in much of what today is Nevada and Utah. That war halted service from early May 1860 into July of that year and made travel in the region risky into October. Stations burned by the Paiutes had to be replaced, and the often overlooked war reportedly cost Russell, Majors & Waddell $75,000. To make up for lost business, the Pony started moving mail more than once a week, twice on average. But the Civil War came along, and Edward Creighton and his associates completed the transcontinental telegraph in unexpectedly fast time. That put the Pony down for good.

Most chroniclers of the story of the Pony Express have been little interested in how this’saga of the saddle,’ as one enthusiast called it, became what is in essence an American tall tale. Much of that is easily explained by the odd chronology of the tale. The Pony Express was short-lived and its financial collapse essentially ruined its backers. If Russell, Majors & Waddell left significant records, those have never been discovered. One explanation is simply that they did not keep many records; the other is that they destroyed whatever records they had to avoid creditors. Both Russell and Waddell died within a decade of the end of the Pony Express and never wrote a word about their exploits. Majors, an honest-to-God pioneer in western freighting on the fabled Santa Fe Trail, survived. But Majors, a simple man who was a devout Bible reader, did not compose his memoirs until the end of the 19th century. When he did, his life story was ghostwritten or at least heavily edited by Colonel Prentiss Ingraham, a fabled dime novelist and hack. William ‘Buffalo Bill’ Cody (we will return to Buffalo Bill anon) paid Rand McNally to print this hodgepodge of recollections — Seventy Years on the Frontier: Alexander Majors’ Memoirs of a Lifetime on the Border . Majors later complained that Colonel Ingraham had taken liberties with the story.

Despite the best efforts of enthusiasts, we are not even sure exactly who rode for the Pony Express. Majors said that he had 80 men in the saddle, but this was not the modern American space program. It seems plausible, and many personal anecdotes support this theory, that just about anyone could ride for the Pony if they were available and the Pony needed a rider. Dramatic images (and every painter in America from Frederic Remington to those who wished to be Remington painted the Pony Express) always show a rider at full gallop pursued by Indians or desperadoes. But the few remaining riders who were actually interviewed late in their lives never mentioned Indians or desperadoes. They always complained about the weather, understandable if you were riding a horse across western Nebraska or Wyoming in January at night in a snowstorm. They also complained bitterly about not being paid. Russell, Majors & Waddell were notorious deadbeats. Wags in the American West claimed that the initials C.O.C.& P.P. actually meant ‘clean out of cash and poor pay.’

The first chronicler of the Pony Express was Colonel William Lightfoot Visscher, a peripatetic newspaperman (but not a colonel) who drifted across the American West in the late 19th century. He is, on reflection, a perfect chronicler for such a tale. He never let the facts get in the way of anything he wrote. Visscher’s book A Thrilling and Truthful History of the Pony Express was published in 1908, nearly half a century after the Pony Express went out of business. Anyone wondering how the story of the Pony Express became muddled need only consider that it took half a century to write a book about the subject, and its author was a dubious chronicler.

Much of Visscher’s research appears to have been conducted at the bar of the Chicago Press Club, his legal address for many years. A terrible liar, a drunkard, a bad poet and a rascal, Visscher bore an amazing resemblance to comedian W.C. Fields. The colonel was a delightful if completely unreliable historian. We have no idea where he got most of his information, although he appears to have cribbed a fair bit of it from the few early attempts to set down some facts about the Central Overland. Historians of the Pony, such as there have been, have always ignored this jolly old lush, who drank two quarts of gin a day for much of his life but lived to be 82.

Five years after the colonel took up his pen, along came Professor Glenn D. Bradley at the University of Toledo. The professor did not do much to help the story either, and then he went and got malaria while having a Central American adventure and died. Bradley does not even mention Visscher or his book in his own effort, The Story of the Pony Express: An Account of the Most Remarkable Mail Service Ever in Existence and Its Place in History . It is possible that he never even read Visscher’s work.

After Bradley’s 1913 book, there was a period of dormancy in Pony Express scholarship for some years. But then came several other books, also long on embellishment. Some of them, such as Robert West Howard’s Hoofbeats of Destiny , are full of interesting details but also use fictional characters to drive the story. This does not help sort out the fact from the fancy.

Shakespeare tells us ‘old men forget,’ and the bard was so very right in the matter of the Pony Express. It was well into the 20th century before anyone tried to interview any of the remaining old riders. They either remembered nothing of significance or their memories were fabulous, resulting in wild stories in which the Pony just got bigger and bigger each year in the retelling.

Raymond and Mary Settle made one of the few serious attempts to write a Pony Express history. Their 1955 book Saddles and Spurs: Saga of the Pony Express provides a solid overview but does not consider how the story of the Pony Express came to be. They also failed to recognize that Russell, if not the other owners of the firm, was a con man and rascal of the worst sort. They make no mention of Colonel Visscher, either. Raymond Settle, a Baptist minister, left his papers to William Jewell College in Liberty, Mo. They remain, unsorted and uncataloged, in dusty boxes in the cellar of the college’s library.

The greatest proponent of the Pony Express story in modern times was William Waddell, the great-grandson of William Bradford Waddell. The Pony’s Waddell was actually a mousy bookkeeper who stands in the shadow of cohorts Russell and Majors. But his descendant decided that a spot of revisionism was in order. He obtained the copyright to Professor Bradley’s little book and reissued it in 1960 with his own annotations. There is no mention that it was actually Bradley’s book. What Waddell apparently liked most about Bradley’s account was how it pretty much ignored Alexander Majors, the real hero of the Pony Express, who lived until 1900.

The Pony Express story’s tremendous growth through the years can be explained in no small part by the wonderfully eccentric cast of characters who attached themselves to the tale from its beginning. One of the first was Captain Sir Richard Burton, the British explorer. Burton went down the line of the Pony Express in the summer and fall of 1860, the first credible eyewitness to the venture. A seasoned military man, he took copious notes, and after spending a mere 100 days in the American West produced a 700-page account of his adventures, City of the Saints . Burton provides us with the best solid information we have about conditions along the line. One year later, while Burton was writing his account in London, no less a chronicler of America than Mark Twain appeared on the scene.

The man who would become Mark Twain was merely Sam Clemens, a 25-year-old recent deserter from the Confederate Army when he ran into the Pony Express. Clemens had gone West in a Concord coach with his brother Orion, who was on his way to be secretary to the territorial governor of Nevada. Like Burton, the brothers left from St. Joe, probably from the Patee House, headquarters of the Pony Express. One day in the first week of August 1861 in western Nebraska Territory, near Mud Springs, Sam Clemens saw a Pony Express rider. His description is one of the most powerful bits of eyewitness testimony we have:

Presently the driver exclaims: ‘HERE HE COMES!’

Every neck is stretched further, and every eye stretched wider. Away across the endless dead level of the prairie a black speck appears against the sky, and it is plain that it moves. Well, I should think so! In a second or two it becomes a horse and rider, rising and falling, rising and falling — sweeping towards us nearer and nearer — growing more and more distinct, more and more sharply defined — nearer and still nearer, and the flutter of the hoofs comes faintly to the ear — another instant a whoop and a hurrah from our upper deck, a wave of the rider’s hand, but no reply, and man and horse burst past our excited faces, and go winging away like a belated fragment of a storm! So sudden is it all, and so like a flash of unreal fancy, that but for the flake of white foam left quivering and perishing on a mail sack after the vision had flashed by and disappeared, we might have doubted whether we had seen any actual horse and man at all, maybe.

Twain’s encounter with the Pony Express — he probably saw one rider — took all of two minutes. But writing from memory and without notes a decade later in Hartford, Conn., he got two whole chapters in Roughing It out of the experience, which shows you what you can do with your material if you are Mark Twain. While Burton loathed the West, complaining nonstop of fleas and flies and filth and Indians and stupid Irishmen, Twain had a grand time. But both writers left us a lot of solid information — what sort of food the men ate, the clothing they wore and descriptions of the stations, most of which were hovels — that is not available anywhere else.

Buffalo Bill Cody (1846-1917), though, is the reason Americans remember the Pony Express today. In essence, Buffalo Bill saved the memory of that enterprise. Long before there were books about the Pony Express, let alone motion pictures, Buffalo Bill’s Wild West presented the Pony Express rider — a fixture in Cody’s extravaganza from the day it opened in Omaha, Neb., in 1883 until the day it closed in 1916.

Not only Americans became dramatically acquainted with the Pony Express through Buffalo Bill; Europeans from penniless orphans in London (let into the show because of kind-hearted Cody) to Queen Victoria, Kaiser Wilhelm and the pope in Rome had the same pleasure. Part of Cody’s enthusiasm for celebrating this bit of the Wild West was that in his youth, he had actually known Alexander Majors. After Cody’s father died, Majors gave the boy (who was about 11 at the time) a job, riding a pony or a mule as a messenger for the freight-hauling firm. Never shy of embellishing his past, Cody always claimed to have ridden for the Pony Express — and ridden the longest distance, too! That claim, however, like so many of his yarns, is highly dubious (see accounts of his alleged Pony adventures in a related story, P. 38). The best examination of his boyhood, undertaken by a forensic pathologist with an interest in history, would seem to indicate that Cody never sat in the saddle for the Central Overland. He did, however, do a great deal for the memory of the Pony Express. Without his devotion, it is unlikely that anyone would remember the horseback mail service. Because of Buffalo Bill, people who did not speak a word of English knew what the Pony Express was. Even today there are Pony Express clubs in Germany and Czechoslovakia, reminders of Buffalo Bill’s legwork on behalf of the fast mail.

Students of the story of the Pony Express will note that its memory waxes and wanes. In about 1960 on the occasion of its centennial, the memory was sweetened when the Eisenhower administration (Ike was from Kansas, Pony Express country) festooned the West with historic markers recalling the days of saddles and spurs. Many western towns boast ‘authentic Pony Express stations,’ but the provenance of those shrines is best left unexplored. Like so much of the memory of the Pony Express, the more one knows about the story, the more fractured and fabulous it becomes. There is hardly a gift shop or historic shrine between Old St. Joe and Old Sac that does not sell an ‘authentic’ Pony Express rider recruiting notice.

The company recruited daredevils, placing eye-catching notices in the St. Louis and San Francisco newspapers that read: ‘Wanted. Young, Skinny, Wiry fellows not over 18. Must be expert riders willing to risk death daily. Orphans preferred. Wages $25.00 per week.’ Alas, it appears that this memorable ad was the work of an early 20th-century journalist writing in the Western magazine Sunset .

In the 1920s, a remnant of what had been the U.S. cavalry in California tried to reenact a bit of the ride as a kind of exercise and found it too difficult. Frankly, in the 21st century we do not have horsemen or women who can ride like that any longer. Men are not born in the saddle now, and even the most accomplished modern equestrian could not take the mochila from Fort Churchill to Robbers Roost.

The annual reenactment is a wonderful thing to witness. To stand on the edge of a rain-soaked field in central Nebraska and see the lone figure of a man on a galloping horse appear on the distant horizon is still a stirring sight. It is the sight that inspired Mark Twain so long ago. It is the memory that Buffalo Bill Cody loved.

Hollywood has always been especially kind to the memory of the Pony Express. As might be expected, just about all references to it in film (and there were silent films as early as the turn of the last century featuring the Pony Express) are wrong. The entertaining 1953 Paramount movie The Pony Express has Charlton Heston as Buffalo Bill teaming up with Wild Bill Hickok (played by Forrest ‘F Troop’ Tucker) and heading to ‘Old Californy’ to start the Pony Express. There is not a shard of fact in the entire film. (Hickok actually worked for the firm but merely as a stock tender in Nebraska.) Several years ago, the film Hidalgo featured a wild tale of Frank Hopkins, a self-proclaimed equestrian who said that he rode for the Pony Express. Hopkins’ Arabian adventures showcased in the movie are fantasy (see the full story in the October 2003 Wild West ), and let it further be said that Hopkins most likely wasn’t even born when the real Pony riders were hitting the trail.

The memory of the Pony Express remains sweet. In the years in which I attempted to follow its trail, I met dozens, perhaps hundreds of Americans, who believe that their great-great-grandpas rode for the Pony, as the old-timers in the West still affectionately call it. There are so many people out there with ancestors who rode for the Pony that Russell, Majors & Waddell would not have needed to buy expensive horses but could have lined up all the riders so that the mail passed hand to hand all the way from St. Joseph to Sacramento.

A cursory examination of early 20th-century newspapers in the American West will amply illustrate that they regularly reported the death of the last Pony Express rider. The Tonopah Bonanza reported it on April 3, 1913, with the death of 76-year-old Louis Dean. A year later the same newspaper reported that another ‘last of the Pony Express riders’ was gone. This time he was Jack Lynch. The Reno Evening Gazette frequently dusted off the story, one of the best being the news of the death of James Cummings, the last of the Pony Express riders, dead at age 76 on March 3, 1930. He would have been riding for Russell, Majors & Waddell at age 6 or 7.

Broncho Charlie Miller, charming but no doubt full of beans, was the last man to claim the title of ‘last of the Pony Express riders.’ When the old boy died at Bellevue Hospital in New York City on January 15, 1955, ‘the brotherhood of the Pony Express riders wound up its affairs’ as one obituary put it. Miller was a delightful end piece to the story of the Pony Express. He claimed to have been born on a buffalo robe in a Conestoga wagon going west in 1850. His claims to have ridden for the Pony — a run that would have taken him up from Sacramento over the Sierra Nevada and down into Carson City, Nev. — were lively. He would have been 10 or 11.

A former rider and showman with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West (that part is true), Miller was the king of ‘the Last of the Pony Express riders.’ A charming rascal and shameless self-promoter who had Old West written all over his face and attire (and that played best in the East), Miller was a chain-smoking, hard-drinking admitted horse thief. But America forgave him. Pony Express purists and doubters regularly challenged the old boy, but they never laid a glove on him. He refused to even acknowledge that there were purists and doubters of his tales. America loved Broncho Charlie Miller, whether he was telling the truth or not. He was, in the words of The New York Times , ‘the incarnation of the Old West for thousands of delighted youngsters — and some folks not so young.’

When Miller was an old man — 82 if we believe his birth date — he rode an old horse named Polestar from New York City to San Francisco to remind America, lest it forget, that the Pony Express had once brought the mail. People stood in the streets and cheered to see the old man loping along. He took a crazy, circuitous route that did not follow the route of the Pony Express and rode hundreds of miles into the Southwest. Go figure.

Despite all the rascals and scamps associated with the story of the Pony Express, admirers of the bold venture will be cheered to learn that there were actual heroes. One of those was Robert Haslam, or Pony Bob, a legendary fast mail rider in the real 19th-century American West. An Englishman who came to Utah as a teenager at the time of the Mormon migration, Haslam rode for the Pony in Nevada at the time of the Paiute War, making a fabled ride of nearly 400 miles without relief. He later rode express mail for Wells, Fargo & Co., elsewhere in the West and was long associated with Buffalo Bill’s Wild West, but Haslam died in a cold water flat on the south side of Chicago in 1912, forgotten. Haslam was the real deal. We have a vivid eyewitness account in the Territorial Enterprise , the newspaper where Mark Twain cut his teeth, of a race on the Fourth of July in 1868. This account leaves no doubt that Haslam was a fabled Pony Express rider in his day and that he was a great horseman.

Another of those Americans who helped to save the true story of the Pony Express, or at least as true as it could be, was Mabel Loving. Mrs. Loving was an amateur poetess in St. Joseph. She was a terrible poet but a prolific one, as bad poets often are (Colonel Visscher was a prolific bad poet, too).

Just before World War I, Mabel Loving did something that no one had thought to do. She sat down and began to write to the few surviving members of the Pony Express. Her correspondence with those riders provides us with some of the richest detail we have about that mail service. Loving’s work was a labor of love, and she provided in her will that her little book on the Pony Express be published (no commercial publisher would touch it). Today, if you can find a copy of The Pony Express Rides On! you will pay dearly for it. Imperfect as it is — the printer appears to have actually lost two chapters — it contains some fascinating information about a fabulous time when young men on fast horses could cross the West in 10 days’ time or less.

This article was written by Christopher Corbett and originally appeared in the April 2006 issue of Wild West .

For more great articles be sure to subscribe to Wild West magazine today!

Taking Stock of the Pony Express

This article, which originally appeared in the April 2010 issue of Wild West Magazine received the coveted Western Heritage Award (Wrangler) in the Magazine category.

Young Robert Haslam started as a simple laborer, building way stations for the fledgling Pony Express, but he was soon offered an opening as an express rider—an offer he eagerly accepted and a job at which he quickly excelled. On May 10, 1860, he left his home base at Fridays Station—on the present-day border between California and Nevada—and had little difficulty on his 75-mile run east to Bucklands Station. But by the time the wiry 19-year-old completed his assigned run, the situation had changed.

‘Wanted: Young, skinny, wiry fellows not over 18. Must be expert pony riders willing to risk death daily. Orphans preferred’

The Northern Paiutes were on the warpath, just one month after the Pony Express began service, and the next rider scheduled refused to get in the saddle. Haslam, however, remained undeterred by the Indian scare. Transferring the mail and himself onto a fresh mount, he galloped off on the next leg of the route, a ride that would put Haslam’s name in the history books. Riding over alkali flats and parched desert, he pushed through to Smith Creek, where, after 190 miles, he slid off of his pony for a brief rest before making the even more harrowing return run. Arriving at Cold Springs, Haslam found that the Paiutes had burned the station, killed the keeper and run off the relief horses. By the time he made it back to Fridays Station, “Pony Bob” had covered more than 380 grueling miles. Haslam made another famous ride in March 1861, carrying President Abraham Lincoln’s inaugural address 180 miles from Smith Creek west to Fort Churchill in a record 8 hours and 10 minutes. His dedication was exceptional, but he was not alone. Many Pony riders were willing to risk their backsides to deliver the mail in a timely fashion.

It has been 150 years since one of the most remarkable enterprises in American history carried the mail and the day. Yet, most of us can easily imagine these lone young riders racing the wind across the open plains, fleeing Indian pursuers. Yes, the Pony Express still stirs the imagination, conjuring a romantic but gritty picture. Look a little closer, though, and something else becomes clear: The Pony Express was, despite the Herculean efforts of Pony Bob and his fellows, also a terrible flop.

It is not difficult to find a failed business whose name lives on long after its collapse. History is replete with financially ruinous ventures and misadventures—from Edison Records to Betamax, from Swissair to Titanic ’s White Star Line, and from Charles Ponzi to Bernie Madoff. What is remarkable is for a failed business to be remembered not for its disappointing performance but for its determination and grit. For such a venture to be romanticized, commemorated and held in awe by the public is high praise indeed. That is the legacy of the Pony Express. On the sesquicentennial of the first ride (and, on that of the last ride, less than 19 months off), much of the nation is celebrating and singing the praises of a small group of men—many of them mere boys—who set out to provide a service that ultimately proved an economic failure.

The Pony Express started out as a very good idea. Founders William Russell, Alexander Majors and William Waddell, despite popular myths to the contrary, were not rough drovers or confidence men. Rather, they were well-established businessmen with a successful record of providing freight service to both the U.S. Army in the West and civilian mercantile efforts, which included the movement of merchandise over the Santa Fe Trail. These men recognized a need for improved communications between the Eastern United States and the burgeoning communities in California. With more than a half-million people already settled west of the Rocky Mountains, and the growing likelihood of a Civil War, the federal government was determined to establish and maintain more regular contact with an area rich in natural resources and susceptible to disruptive inroads by an increasingly belligerent South.

Russell, Majors and Waddell also saw an opportunity to compete for a million-dollar government contract for dedicated mail service to the region. The partners planned to fulfill the contract with their already established Central Overland California and Pikes Peak Express Company, of which the proposed Pony Express would be a subsidiary operation. From a business perspective, the enterprise seemed solid, especially considering the likelihood of Civil War. In wartime, service demands would surely skyrocket, and the resultant profits were bound to be enormous.

With these considerations in mind, Russell, Majors and Waddell set out to create the infrastructure that would allow them to pull off this daring scheme. Whereas communications links were good from the East Coast as far west as Missouri, anything from Kansas westward was problematic at best. Thus the challenge for these entrepreneurs was to come up with a support system to facilitate their plans.

They established a headquarters at the Patee House in St. Joseph, Mo., and selected a trail that ran west from St. Joe over the existing Central Overland route—to Marysville, Kan., northwest along the Little Blue River to Fort Kearny (near present-day Kearney, Neb.); from there along the Platte River Road and across a corner of Colorado Territory before swinging north to pass Courthouse Rock, Chimney Rock and Scotts Bluff and reach Fort Laramie (in what would become Wyoming); then up to Fort Caspar, through the South Pass to Fort Bridger and on into Utah Territory. The final leg went through Salt Lake City, on into Nevada and across the Sierra Nevada, finally ending in Sacramento, Calif. From Sacramento the mail would be forwarded by steamboat to the Pony Express offices in bustling San Francisco. The total distance covered would amount to nearly 2,000 miles.

Some stagecoach stations were already up and running, but the partners would have to place and construct many more. Ultimately, about 190 way stations covered the route, each spaced from 10 to 15 miles apart—the approximate range a medium-sized horse could sustain at a gallop. Some of these stations would become fairly elaborate affairs, comprising stables, bunkhouses, even taverns and a post office. Most, however, would remain rudimentary structures, offering a single-story cabin for the station keeper, a corral and a roughed-in shelter for spare horses. Establishing the stations was only the first step. Each would have to be equipped and manned. The service would require 400 station hands, including skilled farriers, as well as 500 horses and at least 200 riders.

Considering the combined weight of the mail and the gear to be carried at a gallop by each horse, the riders would necessarily have to weigh no more than 125 pounds. Waddell published ads for riders and others, but the oft-reprinted flier WANTED: YOUNG, SKINNY, WIRY FELLOWS NOT OVER 18. MUST BE EXPERT PONY RIDERS WILLING TO RISK DEATH DAILY. ORPHANS PREFERRED was probably a later concoction.

These wiry young fellows would be expected to ride at a gallop the 10 to 15 miles between way stations, quickly change mounts and repeat that pattern until they reached their other “home station,” between the 75- and 150-mile mark. At this point, the next rider would take charge of the mail and begin his run, the idea being to move the mail from St. Joseph to Sacramento in 10 days. It could be a grueling job—tough on both men and horses—and thus the wages offered, $25 per week, were high at a time when an unskilled laborer received an average of $1 per day for 12 hours of work. While the work of a Pony rider was both strenuous and dangerous, it was not considered an excuse for bad behavior. Each rider had to swear an oath to conduct themselves honestly and refrain from cursing, fighting or abusing their animals. Each was then issued a small leather-bound Bible.

“Pony Bob” Haslam’s heroics stand out, but plenty of other venturesome young men answered Waddell’s summons. Among them was Missouri horse racer Johnny Frey (often spelled Fry), who would later enlist in the Union Army, only to be shot down by Rebel guerrilla “Bloody Bill” Anderson’s followers at Baxter Springs, Kan. He is often credited with being the first rider to head west out of St. Joseph, on the evening of April 3, 1860, although that remains in dispute. Others—including Henry Wallace, Billy Richardson and Alex Carlyle—also claimed to have been the first to gallop westward.

The first rider heading east out of Sacramento was probably William Hamilton. Restless young William Frederick Cody—who would go on to win fame as scout and showman “Buffalo Bill”—either rode for the Pony or did not, depending on whose version of events you believe. Les Bennington, National Pony Express Association president, is one who doubts young Cody actually rode for the Pony, but adds, “I cut him some slack, because even if he didn’t dispatch mail at that time, he later kept the vision and memory alive by featuring the Pony Express at all his Wild West shows.”

While the riders were the stars of the Pony Express, they had a strong supporting cast. William Finney, for one, was a pugnacious station agent posted in San Francisco who bulldogged reconstruction of the Pony Express line after the Pyramid Lake War (May–August 1860). Despite popular legend, James Butler Hickok, later known as the famous lawman and shootist “Wild Bill,” was never a rider. He was too big and far too old (he was 23 when the service began). Rather, Hickok was an assistant keeper at Rock Creek Station in southeastern Nebraska (near the present-day town of Endicott). It was there he got into an argument with former property owner David McCanles and two of his companions. The ensuing gunfight left McCanles and his associates dead and Hickok with a reputation as a fearless gunfighter.

Wranglers carefully selected the horses that carried the young riders. The mounts stood an average of 14½ hands (58 inches) high and weighed no more than 900 pounds. Though smaller and lighter than most horses, they were not, strictly speaking, “ponies.” In fact, they represented various breeds—Morgan, mustang, pinto, even thoroughbred. But all were specially chosen for their strength and endurance.

With riders and horses assembled, the service was left to equip them for the job. Riders carried the mail in a leather saddle cover called a mochila (Spanish for “knapsack”). Designed with a hole for placement over the saddle horn and a slit partially up the back, the mochila was held in place by the rider’s weight. Each mochila comprised four reinforced leather boxes, or cantinas , each secured with a small, heart-shaped brass padlock. The four cantinas could carry about 20 pounds of mail in all.

A rider’s standard gear also included a canteen, a Bible, a brace of revolvers (or one revolver and one rifle, depending upon the rider’s preference) and a small horn, or “boob,” used by the rider to alert a station keeper of his imminent arrival. The combined weight of the rider, mail and accoutrements came to about 175 pounds. The service eventually trimmed that weight by stripping riders of their additional weapons and Bibles.

The routes were demanding, making it imperative that men and horses maintain top physical condition—an expensive proposition. Conditions at home stations, while not luxurious, were quite comfortable, and the food was often very good. Some home stations acquired such good reputations for well-prepared meals that they drew customers from miles around, eager to share the riders’ fare. The horses, for their part, weren’t left to graze but given nutrient-rich feed shipped from Iowa farms to each station—again a very costly proposition.

As it turned out, the rates charged for Pony mail—as much as $5 per half-ounce—could not cover daily expenses. While this seems a self-defeating proposition, it may well be that Russell, Majors and Waddell simply saw it as a necessary expenditure in view of their other business ambitions. Given the positive press generated by the Pony Express and the potential new contracts that press might garner in their freighting and stagecoach services, the business trio probably saw the debt incurred as a very legitimate “sunk cost” investment on potential future return.

The early reputation of the service supports this view. Mail was delivered at record speed. Newspaper coverage was uniformly positive, even laudatory, and the exploits of the riders were celebrated in ubiquitous dime novels and magazine series. But circumstances, fate and fiscal realities were to play pivotal roles in the organization’s future. Delivery, while fast and remarkably reliable, was exceptionally costly for that time. Charging rates as high as $15 for delivery of a single item, the Pony Express, while attractive to the general public, was almost invariably a prerogative of the very well-off. Russell, Majors and Waddell soon found that their enterprise, for all its glamour and public acclaim, was hemorrhaging money.

Making matters worse for the firm was the unanticipated conflict with Northern Paiute Indians and their allies. When Nevada businessman J.O. Williams abducted two young Paiute women, reportedly for illicit purposes, local tribes were quick to react—particularly since the father of one was a prominent Paiute warrior. In a retaliatory strike on May 6, 1860, angry warriors raided the Williams establishment, which housed a saloon and general store and served as both a stagecoach and Pony Express station. The Paiutes set the way station afire, killed three of the workers (Williams was away at the time) and then unleashed their wrath on other nearby stations. To the Paiutes, the Pony Express and its stations were emblematic of the encroaching white man and thus legitimate targets.

The Pyramid Lake War was not especially costly in terms of lives—each side suffered fewer than 200 casualties, small potatoes for a nation engaged in Civil War. But the fighting and its aftermath devastated the Pony Express. The Paiute warriors destroyed numerous stations and killed 16 employees, including one rider. The company actually suspended delivery for three weeks, and when it initially resumed, service was considerably slower. At one point, riders dared not cross the conflict zone without an accompanying cavalry detachment, which in turn reduced their rate of travel to a mere 40 miles per day.

The costs to reestablish the line were staggering. When Russell, Majors and Waddell ran up the damages incurred by the Pyramid Lake War, the total was more than $75,000, much of that to rebuild way stations and stables and replace equipment. When one considers that the initial cost of establishing the entire network of stations was $100,000, the impact of this setback becomes much more stark. And the day-to-day maintenance of the line and services continued to add up. Over the course of its operation, the Pony Express cost its owners $30,000 per month, or $480,000 for its duration. Thus, their enterprise not only failed to make a profit, but also incurred a significant loss of more than $200,000.

Adding to the discomfiture of Russell, Majors and Waddell were economic and political factors over which the partners had absolutely no control. The government contract for expanded mail delivery they had hoped to land for their Central Overland California and Pikes Peak Express Company fell apart, and the Butterfield Overland Stage began operations along the western division (from Salt Lake City to Sacramento) of the central route. In January 1861, Russell—his company bankrupt—signed over most of his holdings to his largest creditor, “Stagecoach King” Ben Holladay. In April 1861, Wells Fargo took over the Pony’s western leg and significantly reduced the cost of postage (which eventually fell as low as $1 a half-ounce). The Pony had become more affordable, but it was too little too late.

The outbreak of Civil War, contrary to expectations, also had a disruptive effect on government mail contracts. As the central Eastern seaboard devolved into a sprawling battlefield, affairs in the West took on diminished significance. The final nail in the coffin of the Pony Express was completion of the transcontinental telegraph at Salt Lake City on October 24, 1861. Two days later, the Pony Express ceased operations. The great experiment was over.

A major American enterprise had failed, but it was hardly the end of the world. Telegraphs were convenient, and stagecoaches kept the mail coming. And business boomed after the war as the country reunited and people sought new opportunities in the West. After completion of the transcontinental railroad on May 10, 1869, mail was delivered at speeds that soon made the Pony Express seem quaint. But it also seemed romantic, even more so through the years, as trains, trucks and planes mechanized mail delivery. Today, the Pony stands out among other failed enterprises, remembered not for its flaws and ultimate failure but for its mythical resonance. For almost 19 months, a relatively small group of daring young men galloped across the plains, forded streams, outran hostile Indians, braved blizzards and clattered along mountain trails. In sum they covered more than 650,000 miles and carried 374,753 pieces of mail. And, as far as anyone can determine, only one or two mochilas of mail went missing. It is small wonder, then, that 150 years later we still celebrate the Pony Express, not for the business failure it was but for the ideal it represented —humans overcoming time, distance, terrain and the elements to deliver the mail.

Frederick J. Chiaventone, a former Army officer who taught guerrilla warfare and counterterrorist operations at the U.S. Army Command & General Staff College, is now an award-winning novelist, screenwriter and commentator. Suggested for further reading: Orphans Preferred: The Twisted Truth and Lasting Legend of the Pony Express , by Christopher Corbett, and Saddles and Spurs: The Pony Express Saga , by Raymond W. Settle and Mary Lund Settle.

More Pony Express Articles

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

150 Years Later, Pony Express Rides On In Legend

Frank Morris

A stamp from a piece of mail delivered by the Pony Express. In the early days of the enterprise, it cost almost $100 in today's dollars to mail a letter across the country. Wikimedia Commons hide caption

A stamp from a piece of mail delivered by the Pony Express. In the early days of the enterprise, it cost almost $100 in today's dollars to mail a letter across the country.

The Pony Express dispatched its first rider from St. Joseph, Mo., on April 3, 1860. It was an all-out, high-speed information delivery service that traversed nearly 2,000 miles of open, desolate and hostile land.

The goal was to bring faster mail service to California. As a business proposition, it was a total failure. The service was expensive -- $5 a letter (more than $100 by today's standards). But as a Western legend, the Pony Express has been going strong for 150 years.

Delivering The News And Mail Faster

In 1860, the American West was booming, and the East was boiling. Civil war was at hand. A vast wilderness and high mountains blocked the rich West from the rest of the country.

Rail and telegraph lines stopped in St. Joseph. It took a month for news reports and government dispatches to cross that information abyss by stagecoach, says Cindy Daffron, director of the Pony Express National Museum .

"This is what people [in the West] didn't like -- they were living out there with money," says Daffron. "The fastest means was four weeks, so the idea became, 'How do we do it faster?'"

A stagecoach line ran through the country to the south, but that territory was increasingly hostile to the Union. A shorter but rougher trail took a northerly route over the mountains.

Historian Gerry Chilcote says a struggling freight company called Russell, Majors and Waddell was already using it. "And so they came up with the idea of, 'why not carry the mail and get a government contract?'" says Chilcote.

Riders galloping 24/7 and relaying a mail bag from horse to horse and man to man could cover the distance in 10 days. The first Pony Express rider arrived in Sacramento, Calif., on April 13, 1860, and received quite a reception.

"Banners were hung across the street," says Joe Nardone, master historian for the Pony Express Trail Association. "It was lined -- people were cheering."

Nardone is also among the modern Pony Express enthusiasts who re-enact the ride every year.

Legendary Folklore

Back in 1860, riding for the Pony Express was difficult work -- riders had to be tough and lightweight. There's a famous advertisement that reportedly read: "Wanted: Young, skinny, wiry fellows not over eighteen. Must be expert riders, willing to risk death daily. Orphans preferred."

But like a lot of things associated with the Pony Express, that ad may be just another tall tale that grew out of an absence of hard information. Even the name of the first rider is disputed.

"This is a company that kept no records whatsoever," says Chilcote, "They didn't know who the riders were two years afterwards, so a lot of this is 'fakelore,' we call it."

Today you can drive much of the route the Pony Express followed, but aside from a couple of old station buildings and markers, there isn't much to see. The legend of the Pony Express, though, is still going strong.

Web Resources

Author Christopher Corbett wrote the book Orphans Preferred: The Twisted Truth and Lasting Legend of the Pony Express . He says there's a good reason the mail service is still remembered today.

"It doesn't have the baggage of the slaughter of buffalo and the decimation of Indians," says Corbett. "I think that's part of its appeal."

Corbett says Buffalo Bill's Wild West show probably did the most to keep the legend of the Pony Express alive. He says the show, which toured the world, always included the Pony Express in its productions.

Nearly all portrayals of the Pony Express stretch the truth, Corbett says. Lucky for his research, some of the original riders were asked about their experience before they died.

"Buffalo Bill" Cody probably did the most to keep the legend of the Pony Express alive, says historian Christopher Corbett. Cody included the Pony Express in his popular Buffalo Bill's Wild West show. Hulton Archive/Getty Images hide caption

"Buffalo Bill" Cody probably did the most to keep the legend of the Pony Express alive, says historian Christopher Corbett. Cody included the Pony Express in his popular Buffalo Bill's Wild West show.

"They remembered not outrunning outlaws and Indians -- you know those kind of popular images that we would have," says Corbett. "They remembered how cold it was, and they remembered how dangerous it was if you got off the trail at night in winter."