Physical Review Journals

Published by the american physical society.

- Collections

The Work of Stephen Hawking in Physical Review

To mark the passing of Stephen Hawking, we gathered together his 55 papers in Physical Review D and Physical Review Letters . They probe the edges of space and time, from "Black holes and thermodynamics” to "Wave function of the Universe."

90 citations

Occurrence of singularities in open universes, s. w. hawking, phys. rev. lett. 15 , 689 (1965) – published 25 october 1965, 97 citations, singularities in the universe, phys. rev. lett. 17 , 444 (1966) – published 22 august 1966, 738 citations, gravitational radiation from colliding black holes, phys. rev. lett. 26 , 1344 (1971) – published 24 may 1971, 50 citations, theory of the detection of short bursts of gravitational radiation, g. w. gibbons and s. w. hawking, phys. rev. d 4 , 2191 (1971) – published 15 october 1971, 958 citations, black holes and thermodynamics, phys. rev. d 13 , 191 (1976) – published 15 january 1976, 757 citations, path-integral derivation of black-hole radiance, j. b. hartle and s. w. hawking, phys. rev. d 13 , 2188 (1976) – published 15 april 1976, 1,507 citations, breakdown of predictability in gravitational collapse, phys. rev. d 14 , 2460 (1976) – published 15 november 1976, 2,179 citations, cosmological event horizons, thermodynamics, and particle creation, phys. rev. d 15 , 2738 (1977) – published 15 may 1977, 2,185 citations, action integrals and partition functions in quantum gravity, phys. rev. d 15 , 2752 (1977) – published 15 may 1977, 110 citations, quantum gravity and path integrals, phys. rev. d 18 , 1747 (1978) – published 15 september 1978, 394 citations, bubble collisions in the very early universe, s. w. hawking, i. g. moss, and j. m. stewart, phys. rev. d 26 , 2681 (1982) – published 15 november 1982, milestone 1,974 citations, wave function of the universe, phys. rev. d 28 , 2960 (1983) – published 15 december 1983, 468 citations, origin of structure in the universe, j. j. halliwell and s. w. hawking, phys. rev. d 31 , 1777 (1985) – published 15 april 1985, 134 citations, arrow of time in cosmology, phys. rev. d 32 , 2489 (1985) – published 15 november 1985, 300 citations, wormholes in spacetime, phys. rev. d 37 , 904 (1988) – published 15 february 1988, 113 citations, spectrum of wormholes, s. w. hawking and don n. page, phys. rev. d 42 , 2655 (1990) – published 15 october 1990, 16 citations, wormholes in string theory, alex lyons and s. w. hawking, phys. rev. d 44 , 3802 (1991) – published 15 december 1991, 506 citations, chronology protection conjecture, phys. rev. d 46 , 603 (1992) – published 15 july 1992, 89 citations, evaporation of two-dimensional black holes, phys. rev. lett. 69 , 406 (1992) – published 20 july 1992, 36 citations, kinks and topology change, phys. rev. lett. 69 , 1719 (1992) – published 21 september 1992, 51 citations, origin of time asymmetry, s. w. hawking, r. laflamme, and g. w. lyons, phys. rev. d 47 , 5342 (1993) – published 15 june 1993, 7 citations, quantum coherence in two dimensions, s. w. hawking and j. d. hayward, phys. rev. d 49 , 5252 (1994) – published 15 may 1994, 5 citations, superscattering matrix for two-dimensional black holes, phys. rev. d 50 , 3982 (1994) – published 15 september 1994, 305 citations, entropy, area, and black hole pairs, s. w. hawking, gary t. horowitz, and simon f. ross, phys. rev. d 51 , 4302 (1995) – published 15 april 1995, 71 citations, pair production of black holes on cosmic strings, s. w. hawking and simon f. ross, phys. rev. lett. 75 , 3382 (1995) – published 6 november 1995, 69 citations, probability for primordial black holes, r. bousso and s. w. hawking, phys. rev. d 52 , 5659 (1995) – published 15 november 1995, 39 citations, quantum coherence and closed timelike curves, phys. rev. d 52 , 5681 (1995) – published 15 november 1995, 157 citations, duality between electric and magnetic black holes, phys. rev. d 52 , 5865 (1995) – published 15 november 1995, 74 citations, virtual black holes, phys. rev. d 53 , 3099 (1996) – published 15 march 1996, 176 citations, pair creation of black holes during inflation, raphael bousso and stephen w. hawking, phys. rev. d 54 , 6312 (1996) – published 15 november 1996, 17 citations, evolution of near-extremal black holes, s. w. hawking and m. m. taylor-robinson, phys. rev. d 55 , 7680 (1997) – published 15 june 1997, 26 citations, loss of quantum coherence through scattering off virtual black holes, phys. rev. d 56 , 6403 (1997) – published 15 november 1997, 59 citations, trace anomaly of dilaton-coupled scalars in two dimensions, raphael bousso and stephen hawking, phys. rev. d 56 , 7788 (1997) – published 15 december 1997, 25 citations, models for chronology selection, m. j. cassidy and s. w. hawking, phys. rev. d 57 , 2372 (1998) – published 15 february 1998, 136 citations, (anti-)evaporation of schwarzschild–de sitter black holes, phys. rev. d 57 , 2436 (1998) – published 15 february 1998, 18 citations, bulk charges in eleven dimensions, phys. rev. d 58 , 025006 (1998) – published 12 june 1998, 15 citations, inflation, singular instantons, and eleven dimensional cosmology, s. w. hawking and harvey s. reall, phys. rev. d 59 , 023502 (1998) – published 7 december 1998, 114 citations, gravitational entropy and global structure, s. w. hawking and c. j. hunter, phys. rev. d 59 , 044025 (1999) – published 26 january 1999, 164 citations, nut charge, anti–de sitter space, and entropy, s. w. hawking, c. j. hunter, and don n. page, phys. rev. d 59 , 044033 (1999) – published 28 january 1999, 416 citations, rotation and the ads-cft correspondence, s. w. hawking, c. j. hunter, and m. m. taylor-robinson, phys. rev. d 59 , 064005 (1999) – published 1 february 1999, 23 citations, lorentzian condition in quantum gravity, phys. rev. d 59 , 103501 (1999) – published 29 march 1999, 166 citations, charged and rotating ads black holes and their cft duals, s. w. hawking and h. s. reall, phys. rev. d 61 , 024014 (1999) – published 20 december 1999, 355 citations, brane-world black holes, a. chamblin, s. w. hawking, and h. s. reall, phys. rev. d 61 , 065007 (2000) – published 25 february 2000, 197 citations, brane new world, s. w. hawking, t. hertog, and h. s. reall, phys. rev. d 62 , 043501 (2000) – published 29 june 2000, 52 citations, gravitational waves in open de sitter space, s. w. hawking, thomas hertog, and neil turok, phys. rev. d 62 , 063502 (2000) – published 31 july 2000, 129 citations, trace anomaly driven inflation, phys. rev. d 63 , 083504 (2001) – published 5 march 2001, 200 citations, living with ghosts, s. w. hawking and thomas hertog, phys. rev. d 65 , 103515 (2002) – published 9 may 2002, 28 citations, why does inflation start at the top of the hill, phys. rev. d 66 , 123509 (2002) – published 20 december 2002, 271 citations, information loss in black holes, phys. rev. d 72 , 084013 (2005) – published 18 october 2005, 45 citations, populating the landscape: a top-down approach, phys. rev. d 73 , 123527 (2006) – published 23 june 2006, no-boundary measure of the universe, james b. hartle, s. w. hawking, and thomas hertog, phys. rev. lett. 100 , 201301 (2008) – published 23 may 2008, 118 citations, classical universes of the no-boundary quantum state, phys. rev. d 77 , 123537 (2008) – published 25 june 2008, 33 citations, no-boundary measure in the regime of eternal inflation, james hartle, s. w. hawking, and thomas hertog, phys. rev. d 82 , 063510 (2010) – published 8 september 2010, 35 citations, local observation in eternal inflation, phys. rev. lett. 106 , 141302 (2011) – published 8 april 2011, featured in physics editors' suggestion 488 citations, soft hair on black holes, stephen w. hawking, malcolm j. perry, and andrew strominger, phys. rev. lett. 116 , 231301 (2016) – published 6 june 2016.

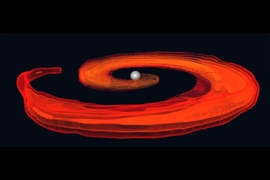

A black hole may carry “soft hair,” low-energy quantum excitations that release information when the black hole evaporates.

Sign up to receive regular email alerts from Physical Review Journals

- Forgot your username/password?

- Create an account

Article Lookup

Paste a citation or doi, enter a citation.

Read 55 of Stephen Hawking’s Research Papers for Free

Read Hawking's takes on black holes and string theory.

Over the course of his life, famed physicist Stephen Hawking wrote dozens of papers that explored the mysteries of time and space. From his 1966 thesis onward, he helped revolutionize the field of astrophysics and define what we know about the universe by diving into topics like string theory, black holes, and the Big Bang .

In the wake of his death last week, the American Physical Society (APS) has released 55 of his studies to “mark the passing of Stephen Hawking.” You can read them here . To fully understand the gravity of what’s going on here, you may want to brush up on your physics: There’s a reason Hawking is considered one of our preeminent geniuses. A huge number of them deal with wormholes and black holes , including this banger on black hole “soft hair,” or zero-energy particles that store information from the stars black holes gobble up.

Hawking helped confirm that black holes are birthed when a star collapses.

These 55 papers are found in the journals Physical Review D and Physical Review Letters , which are published by the APS. These studies, published from 1965 to 2016, the APS states on its site, “probe the edges of space and time.” The first paper published here, “Occurrence of Singularities in Open Universes,” was written a year before his infamous 1966 thesis on expanding universes and marks the start of his work that deals with the universe beginning from a singularity .

Some of the papers also are also an exercise in some fanciful titling by Hawking and his coauthors, including “ Brane New World ” and “ Living With Ghosts .” The latter deals with how gravitational dimensions affect ghost states — which are unphysical states on the wrong side of the kinetic term , and not actually ghosts .

When you’re done with the classics, you can move on over to a new hit titled “A Smooth Exit from Eternal Inflation?” This final paper from Hawking, co-authored with theoretical physicist Thomas Hertog, Ph.D., was submitted two weeks before Hawking’s death and currently exists in its preprint form .

While it doesn’t exactly predict the end of the universe, (something Hawking liked to discuss on in his free time), it does propose a new way to detect the ‘multiverse’: a mathematical road other scientists can explore, ensuring Hawking’s work lives on in the future.

- International edition

- Australia edition

- Europe edition

Stephen Hawking's final scientific paper released

Black Hole Entropy and Soft Hair was completed in the days before the physicist’s death in March

Black holes and soft hair: why Stephen Hawking’s final work is important

Stephen Hawking’s final scientific paper has been released by physicists who worked with the late cosmologist on his career-long effort to understand what happens to information when objects fall into black holes.

The work, which tackles what theoretical physicists call “the information paradox”, was completed in the days before Hawking’s death in March . It has now been written up by his colleagues at Cambridge and Harvard universities and posted online .

Malcolm Perry, a professor of theoretical physics at Cambridge and a co-author on the paper, Black Hole Entropy and Soft Hair, said the information paradox was “at the centre of Hawking’s life” for more than 40 years.

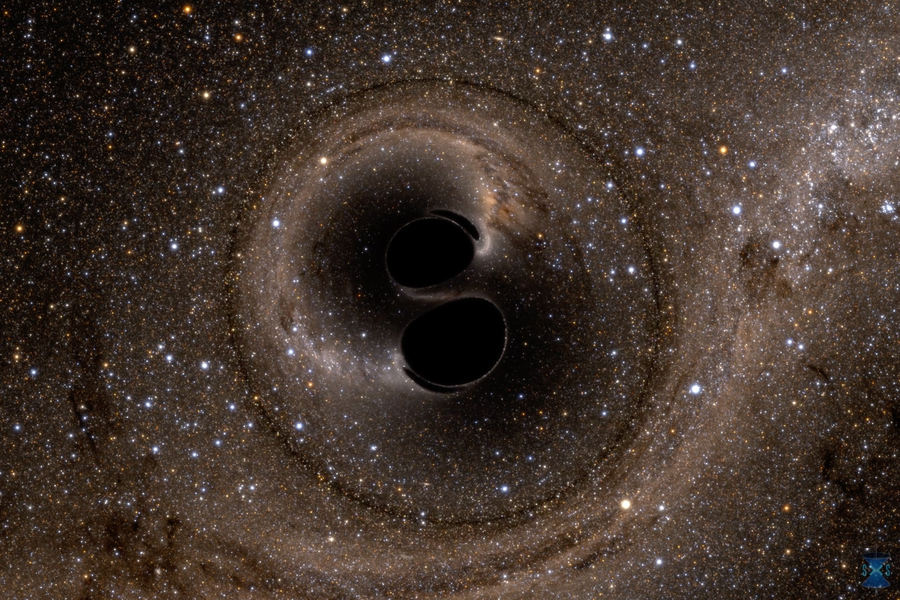

The origins of the puzzle can be traced back to Albert Einstein. In 1915, Einstein published his theory of general relativity, a tour-de-force that described how gravity arises from the spacetime-bending effects of matter, and so why the planets circle the sun. But Einstein’s theory made important predictions about black holes too, notably that a black hole can be completely defined by only three features: its mass, charge, and spin.

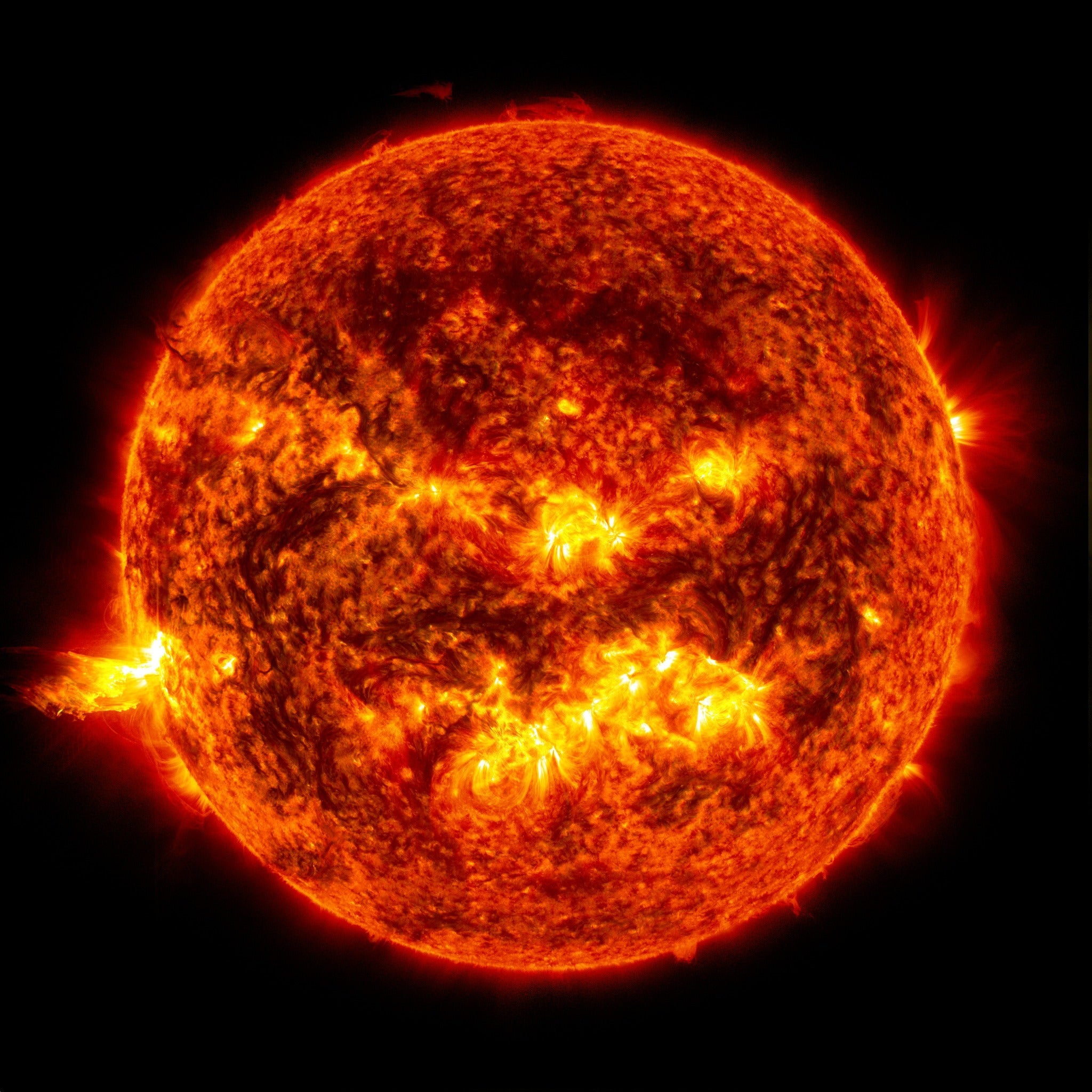

Nearly 60 years later, Hawking added to the picture. He argued that black holes also have a temperature. And because hot objects lose heat into space, the ultimate fate of a black hole is to evaporate out of existence. But this throws up a problem. The rules of the quantum world demand that information is never lost. So what happens to all the information contained in an object – the nature of a moon’s atoms, for instance – when it tumbles into a black hole?

“The difficulty is that if you throw something into a black hole it looks like it disappears,” said Perry. “How could the information in that object ever be recovered if the black hole then disappears itself?”

In the latest paper, Hawking and his colleagues show how some information at least may be preserved. Toss an object into a black hole and the black hole’s temperature ought to change. So too will a property called entropy, a measure of an object’s internal disorder, which rises the hotter it gets.

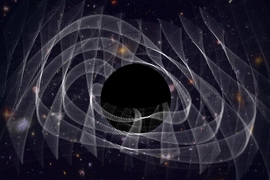

The physicists, including Sasha Haco at Cambridge and Andrew Strominger at Harvard, show that a black hole’s entropy may be recorded by photons that surround the black hole’s event horizon, the point at which light cannot escape the intense gravitational pull. They call this sheen of photons “soft hair”.

“What this paper does is show that ‘soft hair’ can account for the entropy,” said Perry. “It’s telling you that soft hair really is doing the right stuff.”

It is not the end of the information paradox though. “We don’t know that Hawking entropy accounts for everything you could possibly throw at a black hole, so this is really a step along the way,” said Perry. “We think it’s a pretty good step, but there is a lot more work to be done.”

Days before Hawking died, Perry was at Harvard working on the paper with Strominger. He was not aware how ill Hawking was and called to give the physicist an update. It may have been the last scientific exchange Hawking had. “It was very difficult for Stephen to communicate and I was put on a loudspeaker to explain where we had got to. When I explained it, he simply produced an enormous smile. I told him we’d got somewhere. He knew the final result.”

Among the unknowns that Perry and his colleagues must now explore are how information associated with entropy is physically stored in soft hair and how that information comes out of a black hole when it evaporates.

“If I throw something in, is all of the information about what it is stored on the black hole’s horizon?” said Perry. “That is what is required to solve the information paradox. If it’s only half of it, or 99%, that is not enough, you have not solved the information paradox problem.

“It’s a step on the way, but it is definitely not the entire answer. We have slightly fewer puzzles than we had before, but there are definitely some perplexing issues left.”

Marika Taylor, professor of theoretical physics at Southampton University and a former student of Hawking’s, said: “Understanding the microscopic origin of this entropy – what are the underlying quantum states that the entropy counts? – has been one of the great challenges of the last 40 years.

“This paper proposes a way to understand entropy for astrophysical black holes based on symmetries of the event horizon. The authors have to make several non-trivial assumptions so the next steps will be to show that these assumptions are valid.”

Juan Maldacena, a theoretical physicist at Einstein’s alma mater, the Institute for Advanced Studies in Princeton, said: “Hawking found that black holes have a temperature. For ordinary objects we understand temperature as due to the motion of the microscopic constituents of the system. For example, the temperature of air is due to the motion of the molecules: the faster they move, the hotter it is.

“For black holes, it is unclear what those constituents are, and whether they can be associated to the horizon of a black hole. In some physical systems that have special symmetries, the thermal properties can be calculated in terms of these symmetries. This paper shows that near the black hole horizon we have one of these special symmetries.”

- Stephen Hawking

- Black holes

Most viewed

Suggestions or feedback?

MIT News | Massachusetts Institute of Technology

- Machine learning

- Social justice

- Black holes

- Classes and programs

Departments

- Aeronautics and Astronautics

- Brain and Cognitive Sciences

- Architecture

- Political Science

- Mechanical Engineering

Centers, Labs, & Programs

- Abdul Latif Jameel Poverty Action Lab (J-PAL)

- Picower Institute for Learning and Memory

- Lincoln Laboratory

- School of Architecture + Planning

- School of Engineering

- School of Humanities, Arts, and Social Sciences

- Sloan School of Management

- School of Science

- MIT Schwarzman College of Computing

Physicists observationally confirm Hawking’s black hole theorem for the first time

Press contact :, media download.

*Terms of Use:

Images for download on the MIT News office website are made available to non-commercial entities, press and the general public under a Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial No Derivatives license . You may not alter the images provided, other than to crop them to size. A credit line must be used when reproducing images; if one is not provided below, credit the images to "MIT."

Previous image Next image

There are certain rules that even the most extreme objects in the universe must obey. A central law for black holes predicts that the area of their event horizons — the boundary beyond which nothing can ever escape — should never shrink. This law is Hawking’s area theorem, named after physicist Stephen Hawking, who derived the theorem in 1971.

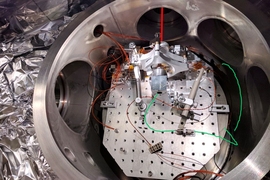

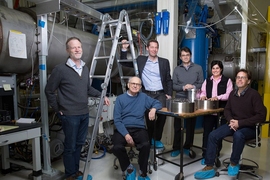

Fifty years later, physicists at MIT and elsewhere have now confirmed Hawking’s area theorem for the first time, using observations of gravitational waves. Their results appear today in Physical Review Letters .

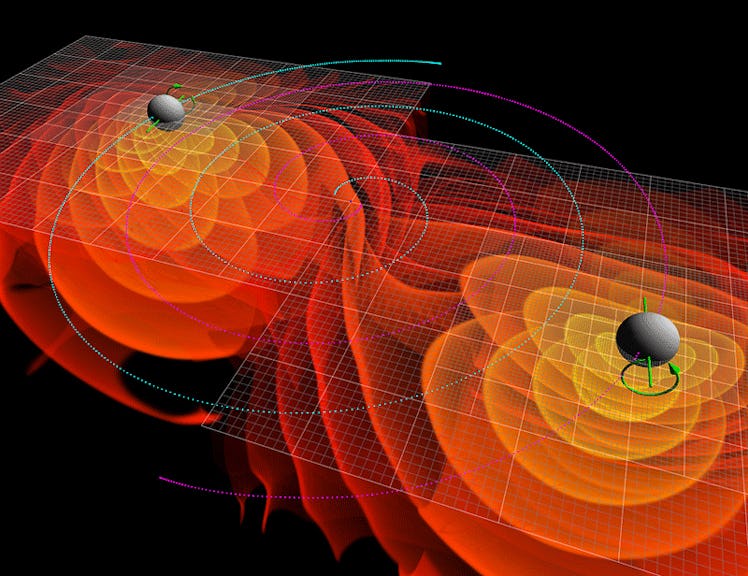

In the study, the researchers take a closer look at GW150914, the first gravitational wave signal detected by the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-wave Observatory (LIGO), in 2015. The signal was a product of two inspiraling black holes that generated a new black hole, along with a huge amount of energy that rippled across space-time as gravitational waves.

If Hawking’s area theorem holds, then the horizon area of the new black hole should not be smaller than the total horizon area of its parent black holes. In the new study, the physicists reanalyzed the signal from GW150914 before and after the cosmic collision and found that indeed, the total event horizon area did not decrease after the merger — a result that they report with 95 percent confidence.

Their findings mark the first direct observational confirmation of Hawking’s area theorem, which has been proven mathematically but never observed in nature until now. The team plans to test future gravitational-wave signals to see if they might further confirm Hawking’s theorem or be a sign of new, law-bending physics.

“It is possible that there’s a zoo of different compact objects, and while some of them are the black holes that follow Einstein and Hawking’s laws, others may be slightly different beasts,” says lead author Maximiliano Isi, a NASA Einstein Postdoctoral Fellow in MIT’s Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research. “So, it’s not like you do this test once and it’s over. You do this once, and it’s the beginning.”

Isi’s co-authors on the paper are Will Farr of Stony Brook University and the Flatiron Institute’s Center for Computational Astrophysics, Matthew Giesler of Cornell University, Mark Scheel of Caltech, and Saul Teukolsky of Cornell University and Caltech.

An age of insights

In 1971, Stephen Hawking proposed the area theorem, which set off a series of fundamental insights about black hole mechanics. The theorem predicts that the total area of a black hole’s event horizon — and all black holes in the universe, for that matter — should never decrease. The statement was a curious parallel of the second law of thermodynamics, which states that the entropy, or degree of disorder within an object, should also never decrease.

The similarity between the two theories suggested that black holes could behave as thermal, heat-emitting objects — a confounding proposition, as black holes by their very nature were thought to never let energy escape, or radiate. Hawking eventually squared the two ideas in 1974, showing that black holes could have entropy and emit radiation over very long timescales if their quantum effects were taken into account. This phenomenon was dubbed “Hawking radiation” and remains one of the most fundamental revelations about black holes.

“It all started with Hawking’s realization that the total horizon area in black holes can never go down,” Isi says. “The area law encapsulates a golden age in the ’70s where all these insights were being produced.”

Hawking and others have since shown that the area theorem works out mathematically, but there had been no way to check it against nature until LIGO’s first detection of gravitational waves .

Hawking, on hearing of the result, quickly contacted LIGO co-founder Kip Thorne, the Feynman Professor of Theoretical Physics at Caltech. His question: Could the detection confirm the area theorem?

At the time, researchers did not have the ability to pick out the necessary information within the signal, before and after the merger, to determine whether the final horizon area did not decrease, as Hawking’s theorem would assume. It wasn’t until several years later, and the development of a technique by Isi and his colleagues, when testing the area law became feasible.

Before and after

In 2019, Isi and his colleagues developed a technique to extract the reverberations immediately following GW150914’s peak — the moment when the two parent black holes collided to form a new black hole. The team used the technique to pick out specific frequencies, or tones of the otherwise noisy aftermath, that they could use to calculate the final black hole’s mass and spin.

A black hole’s mass and spin are directly related to the area of its event horizon, and Thorne, recalling Hawking’s query, approached them with a follow-up: Could they use the same technique to compare the signal before and after the merger, and confirm the area theorem?

The researchers took on the challenge, and again split the GW150914 signal at its peak. They developed a model to analyze the signal before the peak, corresponding to the two inspiraling black holes, and to identify the mass and spin of both black holes before they merged. From these estimates, they calculated their total horizon areas — an estimate roughly equal to about 235,000 square kilometers, or roughly nine times the area of Massachusetts.

They then used their previous technique to extract the “ringdown,” or reverberations of the newly formed black hole, from which they calculated its mass and spin, and ultimately its horizon area, which they found was equivalent to 367,000 square kilometers (approximately 13 times the Bay State’s area).

“The data show with overwhelming confidence that the horizon area increased after the merger, and that the area law is satisfied with very high probability,” Isi says. “It was a relief that our result does agree with the paradigm that we expect, and does confirm our understanding of these complicated black hole mergers.”

The team plans to further test Hawking’s area theorem, and other longstanding theories of black hole mechanics, using data from LIGO and Virgo, its counterpart in Italy.

“It’s encouraging that we can think in new, creative ways about gravitational-wave data, and reach questions we thought we couldn’t before,” Isi says. “We can keep teasing out pieces of information that speak directly to the pillars of what we think we understand. One day, this data may reveal something we didn’t expect.”

This research was supported, in part, by NASA, the Simons Foundation, and the National Science Foundation.

Share this news article on:

Press mentions, popular mechanics.

Researchers from MIT and other institutions have been able to observationally confirm one of Stephen Hawking’s theorems about black holes, measuring gravitational waves before and after a black hole merger to provide evidence that a black hole’s event horizon can never shrink, reports Caroline Delbert for Popular Mechanics . “This cool analysis doesn't just show an example of Hawking's theorem that underpins one of the central laws affecting black holes,” writes Delbert, “it shows how analyzing gravitational wave patterns can bear out statistical findings.”

Previous item Next item

Related Links

- Maximiliano Isi

- MIT Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research

- LIGO Laboratory

- Department of Physics

Related Topics

- Astrophysics

- Kavli Institute

- National Science Foundation (NSF)

Related Articles

Scientists detect tones in the ringing of a newborn black hole for the first time

Quantum measurement could improve gravitational wave detection sensitivity

Could gravitational waves reveal how fast our universe is expanding?

Scientists make first direct detection of gravitational waves

More mit news.

Understanding why autism symptoms sometimes improve amid fever

Read full story →

School of Engineering welcomes new faculty

Study explains why the brain can robustly recognize images, even without color

Turning up the heat on next-generation semiconductors

Sarah Millholland receives 2024 Vera Rubin Early Career Award

A community collaboration for progress

- More news on MIT News homepage →

Massachusetts Institute of Technology 77 Massachusetts Avenue, Cambridge, MA, USA

- Map (opens in new window)

- Events (opens in new window)

- People (opens in new window)

- Careers (opens in new window)

- Accessibility

- Social Media Hub

- MIT on Facebook

- MIT on YouTube

- MIT on Instagram

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Nature Video

- 13 March 2018

Stephen Hawking: Three publications that shaped his career

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

A pop culture icon and ground-breaking physicist, Stephen Hawking is one of the most prominent figures in modern science. Nature Video explores three of the publications that shaped his career and his legacy.

Read the story: Science mourns Stephen Hawking’s death

Read the obituary: Stephen Hawking (1942–2018)

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-018-07819-7

Related Articles

- Communication

These crows have counting skills previously only seen in people

News 23 MAY 24

Harassment of scientists is surging — institutions aren’t sure how to help

News Feature 21 MAY 24

US TikTok ban: how the looming restriction is affecting scientists on the app

News 09 MAY 24

Capturing electron-driven chiral dynamics in UV-excited molecules

Article 22 MAY 24

Imaging surface structure and premelting of ice Ih with atomic resolution

Element from the periodic table’s far reaches coaxed into elusive compound

News 22 MAY 24

Dark energy is tearing the Universe apart. What if the force is weakening?

News Feature 03 MAY 24

Could JWST solve cosmology’s big mystery? Physicists debate Universe-expansion data

News 15 APR 24

‘Best view ever’: observatory will map Big Bang’s afterglow in new detail

News 22 MAR 24

Professor, Division Director, Translational and Clinical Pharmacology

Cincinnati Children’s seeks a director of the Division of Translational and Clinical Pharmacology.

Cincinnati, Ohio

Cincinnati Children's Hospital & Medical Center

Data Analyst for Gene Regulation as an Academic Functional Specialist

The Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität Bonn is an international research university with a broad spectrum of subjects. With 200 years of his...

53113, Bonn (DE)

Rheinische Friedrich-Wilhelms-Universität

Recruitment of Global Talent at the Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (IOZ, CAS)

The Institute of Zoology (IOZ), Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), is seeking global talents around the world.

Beijing, China

Institute of Zoology, Chinese Academy of Sciences (IOZ, CAS)

Full Professorship (W3) in “Organic Environmental Geochemistry (f/m/d)

The Institute of Earth Sciences within the Faculty of Chemistry and Earth Sciences at Heidelberg University invites applications for a FULL PROFE...

Heidelberg, Brandenburg (DE)

Universität Heidelberg

Postdoctoral scholarship in Structural biology of neurodegeneration

A 2-year fellowship in multidisciplinary project combining molecular, structural and cell biology approaches to understand neurodegenerative disease

Umeå, Sweden

Umeå University

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Physical Review D

Covering particles, fields, gravitation, and cosmology, collections.

- Editorial Team

Wormholes in spacetime

S. w. hawking, phys. rev. d 37 , 904 – published 15 february 1988, an article within the collection: the work of stephen hawking in physical review.

- Citing Articles (300)

Any reasonable theory of quantum gravity will allow closed universes to branch off from our nearly flat region of spacetime. I describe the possible quantum states of these closed universes. They correspond to wormholes which connect two asymptotically Euclidean regions, or two parts of the same asymptotically Euclidean region. I calculate the influence of these wormholes on ordinary quantum fields at low energies in the asymptotic region. This can be represented by adding effective interactions in flat spacetime which create or annihilate closed universes containing certain numbers of particles. The effective interactions are small except for closed universes containing scalar particles in the spatially homogeneous mode. If these scalar interactions are not reduced by sypersymmetry, it may be that any scalar particles we observe would have to be bound states of particles of higher spin, such as the pion. An observer in the asymptotically flat region would not be able to measure the quantum state of closed universes that branched off. He would therefore have to sum over all possibilities for the closed universes. This would mean that the final state would appear to be a mixed quantum state, rather than a pure quantum state.

- Received 28 October 1987

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevD.37.904

©1988 American Physical Society

This article appears in the following collection:

The Work of Stephen Hawking in Physical Review

To mark the passing of Stephen Hawking, we gathered together his 55 papers in Physical Review D and Physical Review Letters . They probe the edges of space and time, from "Black holes and thermodynamics” to "Wave function of the Universe."

Authors & Affiliations

- Department of Applied Mathematics and Theoretical Physics, University of Cambridge, Silver Street, Cambridge CB3 9EW, England

References (Subscription Required)

Vol. 37, Iss. 4 — 15 February 1988

Access Options

- Buy Article »

- Log in with individual APS Journal Account »

- Log in with a username/password provided by your institution »

- Get access through a U.S. public or high school library »

Authorization Required

Other options.

- Buy Article »

- Find an Institution with the Article »

Download & Share

Sign up to receive regular email alerts from Physical Review D

- Forgot your username/password?

- Create an account

Article Lookup

Paste a citation or doi, enter a citation.

Stephen Hawking Archive is saved for the nation

by Stuart Roberts, May 26, 2021

Professor Hawking pictured outside the Department of Applied Mathematics and Theoretical Physics, University of Cambridge. Credit: Andre Pattenden

"Each generation stands on the shoulders of those who have gone before them." Stephen Hawking, 2017

Portrait of Professor Hawking by Andre Pattenden

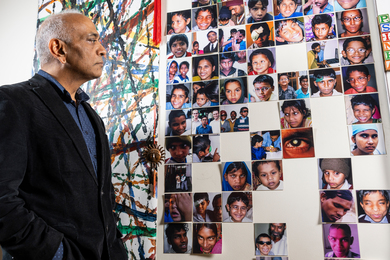

A treasure trove of archive papers and personal objects – from Hawking's seminal works on theoretical physics to scripts from episodes of The Simpsons – are to be divided between two of the UK’s leading cultural institutions following a landmark Acceptance in Lieu (AIL) agreement on behalf of the nation.

The AIL agreement between HMRC, the Department for Culture, Media and Sport, Cambridge University Library, Science Museum Group, and the Hawking Estate, will see around 10,000 pages of Hawking’s scientific and other papers remain in Cambridge, while objects including his wheelchairs, speech synthesisers, and personal memorabilia from his former Cambridge office will be housed at the Science Museum.

The arrival of the archive at the University Library means that three of the most important scientific archives of all time – those of Isaac Newton, Charles Darwin and Stephen Hawking – are now housed under one roof at the iconic Giles Gilbert Scott building. In 2018, Professor Hawking's ashes were buried between the graves of Newton and Darwin at Westminster Abbey.

Professor Hawking pictured with Isaac Newton's annotated first edition of Principia Mathematica , commissioned to celebrate Cambridge University Library's 600th anniversary. Credit: Graham CopeKoga

Under the terms of the historic agreement, Professor Hawking’s extensive Cambridge archive will be cared for and made available to current and future generations of scientists hoping to continue his ground-breaking work in theoretical physics, and will provide future biographers and science historians with an extraordinary gateway and insight into Hawking’s life and work.

Cambridge University Library is already home to manuscripts, books and theses from some of the most famous scientists, mathematicians and astronomers in history including James Clerk Maxwell, JJ Thomson, Ernest Rutherford, Dame Jocelyn Bell Burnell and Dorothy Hodgkin (nee Crowfoot). The UL also safeguards the archives of John Flamsteed, the first Astronomer Royal, and his 19th century successor George Airy.

The University of Cambridge is launching a major fundraising drive to complete the painstaking work of conserving and cataloguing the archive, and to ensure that members of the public are given an opportunity to engage with the archive through a programme of exhibitions, events and digitisation in the Cambridge Digital Library.

Sign up to the newsletter to find out more.

Image captions

“The archive allows us to step inside Stephen’s mind and to travel with him around the cosmos to, as he said, ‘better understand our place in the universe’. “It gives extraordinary insight into the evolution of Stephen’s scientific life, from childhood to research student, from disability activist to ground-breaking, world-renowned scientist. “I am so grateful that the Hawking family and the AIL scheme have entrusted us with this precious archive.”

Dr jessica gardner, cambridge university librarian.

A one of a kind star, NaSt1, observed by Hubble. Credit: NASA

The work to make Professor Hawking’s Cambridge archives available to all follows the now famous 2017 digitisation of his PhD thesis which crashed the University Library’s servers following unprecedented global demand to view and download his 1965 Cambridge doctoral research.

Among the thousands of pages of archive material at the University Library are manuscripts, typescripts and proofs for scientific papers and research, including those written in collaboration or in correspondence with some of the greatest minds of 20th and 21st century theoretical physics, such as Nobel Prize winners Kip Thorne and Sir Roger Penrose.

“This is a proud day for Cambridge. Stephen Hawking was an iconic figure not just in this University and city, but around the world, an inspiration to all who met him, and admired by many, including me.

“his legacy lives on through this archive, which will inspire countless generations of young people with the same ambition as stephen – to challenge our knowledge of, and help us understand our place in, the universe. , “as a hero of 20th and 21st century science, it seems entirely fitting that stephen hawking’s archive joins those of isaac newton and charles darwin at the university library, those giants upon whose shoulders we all stand.” , professor stephen j toope, vice-chancellor, university of cambridge.

Professor Hawking's a rchive also contains letters dating from 1944-2008, his assistants’ notebooks, a list of set phrases for his speech synthesiser, as well as film and TV scripts, such as Oscar-winning film T he Theory of Everything and the iconic sci-fi series The X-Files.

Script for the first-ever episode of the X Files , signed by show creator Chris Carter

Perhaps most fascinating to researchers and scientific historians are artworks and autograph scientific manuscripts from the earliest and arguably most brilliant phase of his career, between 1963 and 1972, after which his physical condition made extended handwriting increasingly difficult.

As part of the AIL agreement, a large collection of photographs with notable figures including Pope Francis and letters to and from former US President Bill Clinton and former presidential candidate Hilary Clinton will also now be housed at Cambridge University Library.

Letter to Stephen Hawkins (sic), by former First Lady Hillary Clinton

Some of the most significant manuscript (handwritten) draft papers include Hawking’s Adams Prize-winning essay ‘Singularities and Geometry of Spacetime’ (1966), ‘Gravitational radiation in an expanding universe’ (1968) and ‘The Event Horizon’ – remarkable for both its late date (1972) and sheer length – providing an opportunity to witness one of the most celebrated scientific minds of his age in the white heat of creative thought.

An early draft copy of the multi-million selling popular science book, A Brief History of Time

The archive also includes a computer print-out of his most famous work A Brief History of Time (then titled From the Big Bang to Black Holes. A Short History of Time ) which would go on to sell 25 million copies, as well as other pre-publication proofs.

Some deeply personal items are evident, too - such as a 1948 letter from a young Stephen to his father, which reads: ‘ Dear Father, here is a story. Once upon a time some pirates were loading treasure on to a ship. Stephen’.

A letter written by the young Stephen Hawking to his father

Other correspondence focuses on his illness, use of wheelchairs and other hardware, as well as issues to do with disabled access and rights.

Professor Hawking’s strong and sometimes fiery personality is also well conveyed by a group of draft letters from 1966, after Hawking had mistakenly understood his work to have been plagiarised by the American physicist Robert Geroch (then a student).

An extract from one of The Simpsons scripts, with Professor Hawking's lines highlighted. Credit: 20th Century Fox

Alongside Albert Einstein, Professor Hawking was unquestionably the most recognisable scientist of the 20th century – beloved by millions around the world for his contributions to science, his books, and a legacy that transcended both scientific and popular culture, leading to an almost rock-star status in his later years. He achieved all this despite a decades-long battle with ALS (Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis), diagnosed while a PhD student at Cambridge University. For 30 years, Hawking was also Lucasian Professor of Mathematics at Cambridge, a position first held by his idol Sir Isaac Newton.

Crab Nebula, as Seen by Herschel and Hubble. Credit: NASA

Professor Hawking's former office at the Department of Applied Mathematics and Theoretical Physics, University of Cambridge. The contents of his office have been acquired by the Science Museum. Credit: Mark Box/Blazej Mikula

Professor Hawking’s iconic former office in the Department of Applied Mathematics and Theoretical Physics at Cambridge University will be faithfully reconstructed at the Science Museum, using the original objects and personal mementos transferred from Cambridge to South Kensington under the terms of the AIL agreement.

“By preserving Hawking’s office and its historic contents as part of the Science Museum Group Collection, future generations will be able to delve deep into the world of a world-leading theoretical physicist who defied the laws of medicine to rewrite the laws of physics and touch the heart of millions."

Sir Ian Blatchford, Director of the Science Museum Group

Professor Hawking pictured at work in his department. Credit: Andre Pattenden

Professor Hawking's rowing jacket, pictured in his office at the Department of Applied Mathematics and Theoretical Physics, University of Cambridge

Blackboard in Professor Hawking's former Department of Applied Mathematics and Theoretical Physics, University of Cambridge

A bust of Professor Hawking at the Department of Applied Mathematics and Theoretical Physics, University of Cambridge

'Be curious' graffiti illustrating Professor Hawking and his work on black holes, Mill Road, Cambridge. Artist unknown. Photo: Hannah Haines

“We are very pleased that these two important institutions will preserve our father’s life's work for the benefit of generations to come and make his legacy accessible to the widest possible audience. Our father strongly believed that everyone should have the chance to engage with science so he would be delighted that his legacy will be upheld by the Science Museum and Cambridge University Library.

“our hope is that our father's scientific career will continue to inspire generations of future scientists to find new insights into the nature of the universe, based on the outstanding work he produced in his lifetime. , “for decades, our father was part of the fabric of life at cambridge university and was a distinguished fellow of the science museum so it seems right that these relationships, so dear to him and us, will continue for many more years to come.” , lucy, tim and robert hawking.

"I hope to inspire people around the world to look up at the stars and not down at their feet; to wonder about our place in the universe and to try and make sense of the cosmos. "Anyone, anywhere in the world should have free, unhindered access to not just my research, but to the research of every great and enquiring mind across the spectrum of human understanding."

Stephen hawking.

Professor Hawking's glasses on his office desk at the Department of Applied Mathematics and Theoretical Physics, University of Cambridge. Credit: Mark Box

Story and design: Stuart Roberts

To find out how you can help, visit The Stephen Hawking Programme. For updates on the archive, including events and opportunities to get involved, please sign up to our newsletter .

With thanks to the Hawking family and Hawking Estate.

We have completed maintenance on Astronomy.com and action may be required on your account. Learn More

- Login/Register

- Solar System

- Exotic Objects

- Upcoming Events

- Deep-Sky Objects

- Observing Basics

- Telescopes and Equipment

- Astrophotography

- Space Exploration

- Human Spaceflight

- Robotic Spaceflight

- The Magazine

What Stephen Hawking’s Final Paper Says (And Doesn’t Say)

Before he died, renowned cosmologist Stephen Hawking submitted a paper, with co-author Thomas Hertog, to an as-yet-unknown journal. Hawking’s last known scientific writing, the paper deals with the concept of the multiverse and a theory known as cosmic inflation. Though the paper currently exists only in pre-print form , meaning it hasn’t completed the process of peer-review, it’s received a significant amount of coverage. “Stephen Hawking’s last paper,” after all, does have a bit of a mythological ring to it.

Stephen Hawking wrote a lot of papers, though. Most dealt with the same sort of heady concepts as his last, and few received such an inordinate amount of attention. Claims that the paper make predictions for the end of universe, or could prove the multiverse exists abound. But it’s worth remembering that the things Hawking thought and wrote about are abstract, they exist largely in the realm of theory. Even more well-known concepts like Hawking radiation have continued to elude scientists, so drawing solid conclusions from any one paper is difficult. Like many topics in theoretical physics, the ideas that Stephen Hawking pondered were so radical and far-out that we usually couldn’t even test them.

And even for one of the brightest minds of our time, the calculations are extremely complex. Hawking and Hertog describe their preliminary theory as a “toy model,” or one that significantly simplifies the real world to make the calculations easier. Such a model wouldn’t necessarily reflect the universe as we see it. No one said theoretical physics was easy.

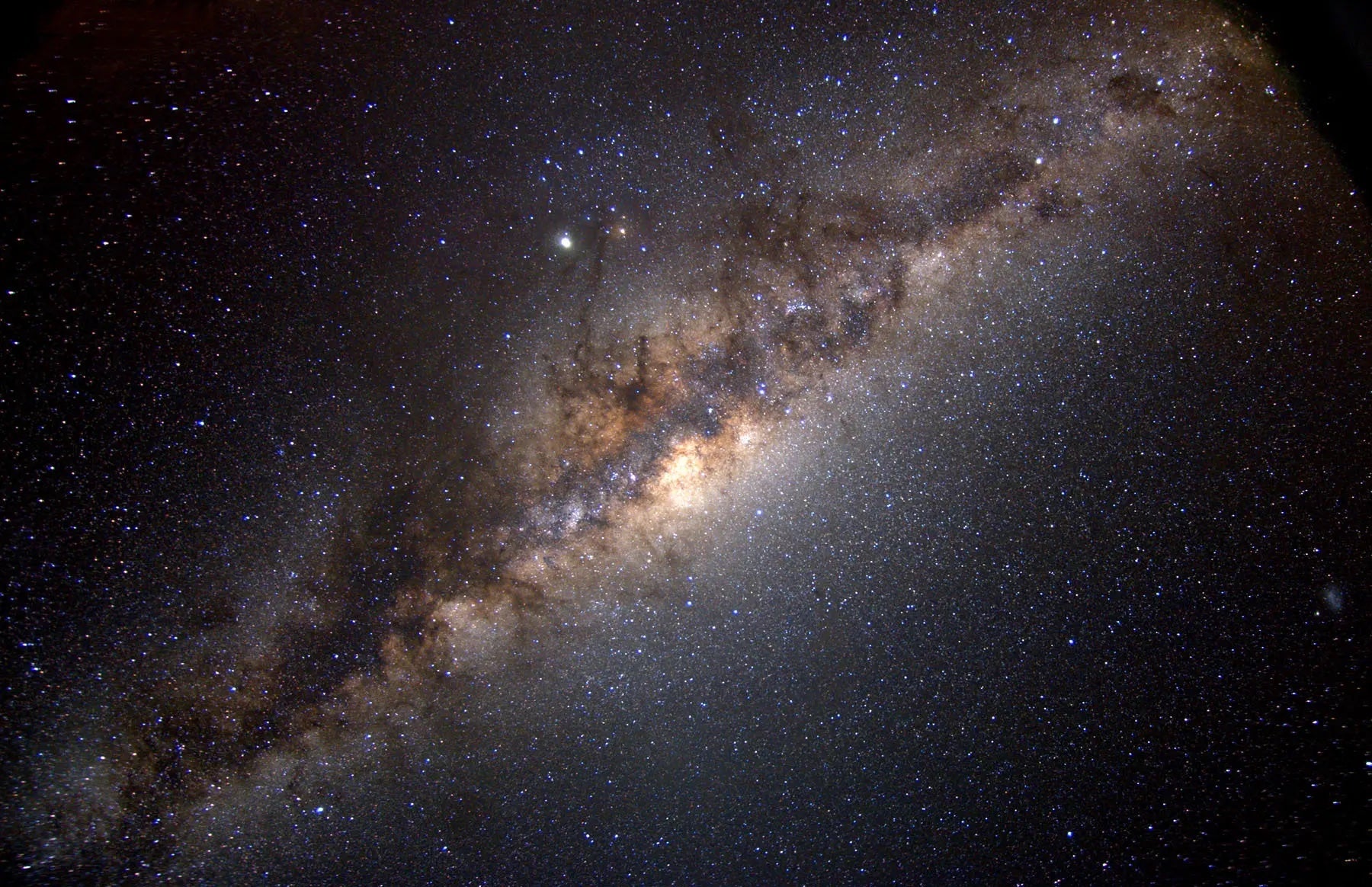

Many Universes Stephen Hawking’s last paper is titled “A Smooth Exit from Eternal Inflation?” It tackles the idea of a multiverse, a vast collection of universes that exist simultaneously, though they’re spread out almost unimaginably far from each other. Multiverses arose, the theory goes, because of something called inflation. In the fractions of a second after our universe emerged, space-time expanded at an immense rate. As it did so, tiny quantum fluctuations expanded to become the large-scale features of the universe we observe today, and which serve as evidence that the theory might be true.

Under a variation of the theory that Hawking and Hertog work with, called eternal inflation, this inflation continues forever in most places, but, in some patches, it stops. Where it stops, universes form — our own and others, in a repeating process that never ends. In these universes, the laws of physics all look different, meaning constants we take for granted like the speed of light would vary between them.

“Eternal inflation creates an infinite number of patch universes, little bubble universes, all over the place with this inflating space between them,” says Will Kinney, a professor of physics at University at Buffalo College of Arts and Sciences.

But an infinite number of universes presents a problem to physicists. One of the most fundamental questions in science is why our universe looks the way it does. Why is the speed of light 186,282 miles per second? Determining the probability of our universe looking the way it does would help scientists get at the answer. Finding probabilities involving infinity is a useless exercise, though. What Hawking and Hertog have done, using a lot of complicated math, is to propose a way that we could define some boundaries on the kinds of universes that might exist.

“It’s like you have a bath full of lots and lots and lots of different kinds of soap bubbles and each soap bubble is a different universe, and there’s a huge variety of different soap bubbles of different shapes,” says Clifford Johnson, a professor in the Physics and Astronomy Department at the University of Southern California. “And what this model is suggesting is a mechanism by which maybe the variety of soap bubbles that are available is not as large as was thought.”

In addition, these universes might look a little more like ours, according to Katie Mack, an assistant professor of physics at North Carolina State University.

“The prediction is for … a smaller number of universes and they would have more in common with each other,” she says. “You could draw more of a straight line between the early universe and what we see today.”

Bringing Clarity If the kinds of universe that could possibly exist is finite, then scientists could begin to understand how and why our universe looks how it does today. Hawking’s paper does not tell us exactly what kind of universes might exist, nor does he definitively prove multiverse or cosmic inflation theories. As Kinney points out, Hawking and Hertog don’t even suggest any ways that we might be able to see evidence of the multiverse, meaning that their theory remains, for the moment, untestable.

The two rely on something called the holographic principle to conduct their work. It’s a way of reconciling quantum mechanics with gravity — the physics of the very large and the very small, as Mack, puts it. The holographic principle states that all of the information in a volume of space is contained in the boundary of the volume. In effect, it compresses a 3-D space into a 2-D space, and the end result is to make the calculations easier.

It’s something that many other researchers use in their work, and Johnson stresses that Hawking and Hertog’s paper, while intriguing, is simply another entry in the field.

“It’s two very good researchers adding a paper to the many very good papers that have been incrementally moving this framework of ideas,” Johnson says.

Hawking himself appears to have been still at work on the theory. Just weeks before his death, he submitted a newer version of the paper containing substantial changes. His co-author Hertog will surely continue to refine the work as well.

In the end, this paper is an interesting hypothesis about how our universe could look on the largest scale. It may not reshape our view of the cosmos — at least not yet — but it adds more intellectual firepower to our collective arsenal. And that’s probably what Stephen Hawking would have wanted.

This article originally appeared on Discovermagazine.com .

2024 Full Moon calendar: Dates, times, types, and names

Starmus VII hit all the right notes from beginning to end

The oldest stars in the universe were swallowed by the Milky Way

Astronomers discover Gliese 12 b, a potentially habitable exoplanet

Astronomers probe deep-space time capsules

The Sun’s magnetic field is generated surprisingly close to its surface, new study suggests

In a cosmic breakthrough, astronomers measure a supermassive black hole’s spin

Ask Astro: How do scientists weigh planets and other celestial objects?

Ancient star streams, named Shiva and Shakti, may be Milky Way’s earliest building blocks

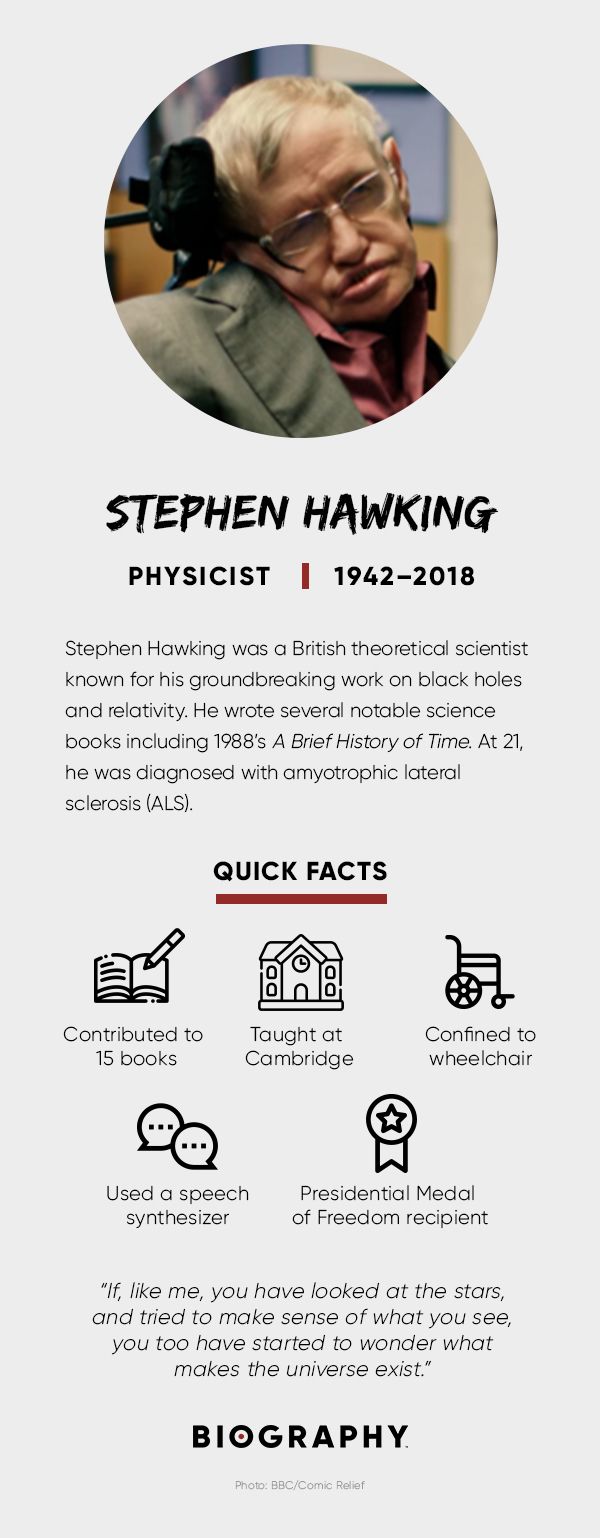

Stephen Hawking

Stephen Hawking was a scientist known for his work with black holes and relativity, and the author of popular science books like 'A Brief History of Time.'

(1942-2018)

Who Was Stephen Hawking?

Stephen Hawking was a British scientist, professor and author who performed groundbreaking work in physics and cosmology, and whose books helped to make science accessible to everyone.

Hawking was born on January 8, 1942, in Oxford, England. His birthday was also the 300th anniversary of the death of Galileo — long a source of pride for the noted physicist.

The eldest of Frank and Isobel Hawking's four children, Hawking was born into a family of thinkers.

His Scottish mother earned her way into Oxford University in the 1930s — a time when few women were able to go to college. His father, another Oxford graduate, was a respected medical researcher with a specialty in tropical diseases.

Hawking's birth came at an inopportune time for his parents, who didn't have much money. The political climate was also tense, as England was dealing with World War II and the onslaught of German bombs in London, where the couple was living as Frank Hawking undertook research in medicine.

In an effort to seek a safer place, Isobel returned to Oxford to have the couple's first child. The Hawkings would go on to have two other children, Mary and Philippa. And their second son, Edward, was adopted in 1956.

The Hawkings, as one close family friend described them, were an "eccentric" bunch. Dinner was often eaten in silence, each of the Hawkings intently reading a book. The family car was an old London taxi, and their home in St. Albans was a three-story fixer-upper that never quite got fixed. The Hawkings also housed bees in the basement and produced fireworks in the greenhouse.

In 1950, Hawking's father took work to manage the Division of Parasitology at the National Institute of Medical Research, and spent the winter months in Africa doing research. He wanted his eldest child to go into medicine, but at an early age, Hawking showed a passion for science and the sky.

That was evident to his mother, who, along with her children, often stretched out in the backyard on summer evenings to stare up at the stars. "Stephen always had a strong sense of wonder," she remembered. "And I could see that the stars would draw him."

Hawking was also frequently on the go. With his sister Mary, Hawking, who loved to climb, devised different entry routes into the family home. He loved to dance and also took an interest in rowing, becoming a team coxswain in college.

Early in his academic life, Hawking, while recognized as bright, was not an exceptional student. During his first year at St. Albans School , he was third from the bottom of his class.

But Hawking focused on pursuits outside of school; he loved board games, and he and a few close friends created new games of their own. During his teens, Hawking, along with several friends, constructed a computer out of recycled parts for solving rudimentary mathematical equations.

Hawking entered University College at the University of Oxford at the age of 17. Although he expressed a desire to study mathematics, Oxford didn't offer a degree in that specialty, so Hawking gravitated toward physics and, more specifically, cosmology.

By his own account, Hawking didn't put much time into his studies. He would later calculate that he averaged about an hour a day focusing on school. And yet he didn't really have to do much more than that. In 1962, he graduated with honors in natural science and went on to attend Trinity Hall at the University of Cambridge for a Ph.D. in cosmology.

In 1968, Hawking became a member of the Institute of Astronomy in Cambridge. The next few years were a fruitful time for Hawking and his research. In 1973, he published his first, highly-technical book, The Large Scale Structure of Space-Time , with G.F.R. Ellis.

In 1979, Hawking found himself back at the University of Cambridge, where he was named to one of teaching's most renowned posts, dating back to 1663: the Lucasian Professor of Mathematics.

DOWNLOAD BIOGRAPHY'S STEPHEN HAWKING FACT CARD

Wife and Children

At a New Year's party in 1963, Hawking met a young languages undergraduate named Jane Wilde. They were married in 1965. The couple gave birth to a son, Robert, in 1967, and a daughter, Lucy, in 1970. A third child, Timothy, arrived in 1979.

In 1990, Hawking left his wife Jane for one of his nurses, Elaine Mason. The two were married in 1995. The marriage put a strain on Hawking's relationship with his own children, who claimed Elaine closed off their father from them.

In 2003, nurses looking after Hawking reported their suspicions to police that Elaine was physically abusing her husband. Hawking denied the allegations, and the police investigation was called off. In 2006, Hawking and Elaine filed for divorce.

In the following years, the physicist reportedly grew closer to his family. He reconciled with Jane, who had remarried. And he published five science-themed novels for children with his daughter, Lucy.

Stephen Hawking: Books

Over the years, Hawking wrote or co-wrote a total of 15 books. A few of the most noteworthy include:

'A Brief History of Time'

In 1988 Hawking catapulted to international prominence with the publication of A Brief History of Time . The short, informative book became an account of cosmology for the masses and offered an overview of space and time, the existence of God and the future.

The work was an instant success, spending more than four years atop the London Sunday Times' best-seller list. Since its publication, it has sold millions of copies worldwide and been translated into more than 40 languages.

‘The Universe in a Nutshell’

A Brief History of Time also wasn't as easy to understand as some had hoped. So in 2001, Hawking followed up his book with The Universe in a Nutshell , which offered a more illustrated guide to cosmology's big theories.

‘A Briefer History of Time’

In 2005, Hawking authored the even more accessible A Briefer History of Time , which further simplified the original work's core concepts and touched upon the newest developments in the field like string theory.

Together these three books, along with Hawking's own research and papers, articulated the physicist's personal search for science's Holy Grail: a single unifying theory that can combine cosmology (the study of the big) with quantum mechanics (the study of the small) to explain how the universe began.

This kind of ambitious thinking allowed Hawking, who claimed he could think in 11 dimensions, to lay out some big possibilities for humankind. He was convinced that time travel is possible, and that humans may indeed colonize other planets in the future.

‘The Grand Design’

In September 2010, Hawking spoke against the idea that God could have created the universe in his book The Grand Design . Hawking previously argued that belief in a creator could be compatible with modern scientific theories.

In this work, however, he concluded that the Big Bang was the inevitable consequence of the laws of physics and nothing more. "Because there is a law such as gravity, the universe can and will create itself from nothing," Hawking said. "Spontaneous creation is the reason there is something rather than nothing, why the universe exists, why we exist."

The Grand Design was Hawking's first major publication in almost a decade. Within his new work, Hawking set out to challenge Isaac Newton 's belief that the universe had to have been designed by God, simply because it could not have been born from chaos. "It is not necessary to invoke God to light the blue touch paper and set the universe going," Hawking said.

At the age of 21, Hawking was diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS, or Lou Gehrig 's disease). In a very simple sense, the nerves that controlled his muscles were shutting down. At the time, doctors gave him two and a half years to live.

Hawking first began to notice problems with his physical health while he was at Oxford — on occasion he would trip and fall, or slur his speech — but he didn't look into the problem until 1963, during his first year at Cambridge. For the most part, Hawking had kept these symptoms to himself.

But when his father took notice of the condition, he took Hawking to see a doctor. For the next two weeks, the 21-year-old college student made his home at a medical clinic, where he underwent a series of tests.

"They took a muscle sample from my arm, stuck electrodes into me, and injected some radio-opaque fluid into my spine, and watched it going up and down with X-rays, as they tilted the bed," he once said. "After all that, they didn't tell me what I had, except that it was not multiple sclerosis, and that I was an atypical case."

Eventually, however, doctors did diagnose Hawking with the early stages of ALS. It was devastating news for him and his family, but a few events prevented him from becoming completely despondent.

The first of these came while Hawking was still in the hospital. There, he shared a room with a boy suffering from leukemia. Relative to what his roommate was going through, Hawking later reflected, his situation seemed more tolerable.

Not long after he was released from the hospital, Hawking had a dream that he was going to be executed. He said this dream made him realize that there were still things to do with his life.

In a sense, Hawking's disease helped turn him into the noted scientist he became. Before the diagnosis, Hawking hadn't always focused on his studies. "Before my condition was diagnosed, I had been very bored with life," he said. "There had not seemed to be anything worth doing."

With the sudden realization that he might not even live long enough to earn his Ph.D., Hawking poured himself into his work and research.

As physical control over his body diminished (he'd be forced to use a wheelchair by 1969), the effects of his disease started to slow down. Over time, however, Hawking's ever-expanding career was accompanied by an ever-worsening physical state.

How Did Stephen Hawking Talk?

By the mid-1970s, the Hawking family had taken in one of Hawking's graduate students to help manage his care and work. He could still feed himself and get out of bed, but virtually everything else required assistance.

In addition, his speech had become increasingly slurred, so that only those who knew him well could understand him. In 1985 he lost his voice for good following a tracheotomy. The resulting situation required 24-hour nursing care for the acclaimed physicist.

It also put in peril Hawking's ability to do his work. The predicament caught the attention of a California computer programmer, who had developed a speaking program that could be directed by head or eye movement. The invention allowed Hawking to select words on a computer screen that were then passed through a speech synthesizer.

At the time of its introduction, Hawking, who still had use of his fingers, selected his words with a handheld clicker. Eventually, with virtually all control of his body gone, Hawking directed the program through a cheek muscle attached to a sensor.

Through the program, and the help of assistants, Hawking continued to write at a prolific rate. His work included numerous scientific papers, of course, but also information for the non-scientific community.

Hawking's health remained a constant concern—a worry that was heightened in 2009 when he failed to appear at a conference in Arizona because of a chest infection. In April, Hawking, who had already announced he was retiring after 30 years from the post of Lucasian Professor of Mathematics at Cambridge, was rushed to the hospital for being what university officials described as "gravely ill," though he later made a full recovery.

Research on the Universe and Black Holes

In 1974, Hawking's research turned him into a celebrity within the scientific world when he showed that black holes aren't the information vacuums that scientists had thought they were.

In simple terms, Hawking demonstrated that matter, in the form of radiation, can escape the gravitational force of a collapsed star. Another young cosmologist, Roger Penrose, had earlier discovered groundbreaking findings about the fate of stars and the creation of black holes, which tapped into Hawking's own fascination with how the universe began.

The pair then began working together to expand upon Penrose’s earlier work, setting Hawking on a career course marked by awards, notoriety and distinguished titles that reshaped the way the world thinks about black holes and the universe.

When Hawking’s radiation theory was born, the announcement sent shock waves of excitement through the scientific world. Hawking was named a fellow of the Royal Society at the age of 32, and later earned the prestigious Albert Einstein Award, among other honors. He also earned teaching stints at Caltech in Pasadena, California, where he served as visiting professor, and at Gonville and Caius College in Cambridge.

In August 2015, Hawking appeared at a conference in Sweden to discuss new theories about black holes and the vexing "information paradox." Addressing the issue of what becomes of an object that enters a black hole, Hawking proposed that information about the physical state of the object is stored in 2D form within an outer boundary known as the "event horizon." Noting that black holes "are not the eternal prisons they were once thought," he left open the possibility that the information could be released into another universe.

Beginning of the Universe

In a March 2018 interview on Neil deGrasse Tyson 's Star Talk , Hawking addressed the topic of "what was around before the Big Bang" by stating there was nothing around. He said by applying a Euclidean approach to quantum gravity, which replaces real time with imaginary time, the history of the universe becomes like a four-dimensional curved surface, with no boundary.

He suggested picturing this reality by thinking of imaginary time and real time as beginning at the Earth's South Pole, a point of space-time where the normal laws of physics hold; as there is nothing "south" of the South Pole, there was also nothing before the Big Bang.

Hawking and Space Travel

In 2007, at the age of 65, Hawking made an important step toward space travel. While visiting the Kennedy Space Center in Florida, he was given the opportunity to experience an environment without gravity.

Over the course of two hours over the Atlantic, Hawking, a passenger on a modified Boeing 727, was freed from his wheelchair to experience bursts of weightlessness. Pictures of the freely floating physicist splashed across newspapers around the globe.

"The zero-G part was wonderful, and the high-G part was no problem. I could have gone on and on. Space, here I come!" he said.

Hawking was scheduled to fly to the edge of space as one of Sir Richard Branson 's pioneer space tourists. He said in a 2007 statement, "Life on Earth is at the ever-increasing risk of being wiped out by a disaster, such as sudden global warming , nuclear war, a genetically engineered virus or other dangers. I think the human race has no future if it doesn't go into space. I therefore want to encourage public interest in space."

Stephen Hawking Movie and TV Appearances

If there is such a thing as a rock-star scientist, Hawking embodied it. His forays into popular culture included guest appearances on The Simpsons , Star Trek: The Next Generation , a comedy spoof with comedian Jim Carrey on Late Night with Conan O'Brien , and even a recorded voice-over on the Pink Floyd song "Keep Talking."

In 1992, Oscar-winning filmmaker Errol Morris released a documentary about Hawking's life, aptly titled A Brief History of Time . Other TV and movie appearances included:

'The Big Bang Theory'

In 2012, Hawking showed off his humorous side on American television, making a guest appearance on The Big Bang Theory . Playing himself on this popular comedy about a group of young, geeky scientists, Hawking brings the theoretical physicist Sheldon Cooper ( Jim Parsons ) back to Earth after finding an error in his work. Hawking earned kudos for this light-hearted effort.

'The Theory of Everything'

In November of 2014, a film about the life of Hawking and Jane Wilde was released. The Theory of Everything stars Eddie Redmayne as Hawking and encompasses his early life and school days, his courtship and marriage to Wilde, the progression of his crippling disease and his scientific triumphs.

In May 2016, Hawking hosted and narrated Genius , a six-part television series which enlists volunteers to tackle scientific questions that have been asked throughout history. In a statement regarding his series, Hawking said Genius is “a project that furthers my lifelong aim to bring science to the public. It’s a fun show that tries to find out if ordinary people are smart enough to think like the greatest minds who ever lived. Being an optimist, I think they will.”

In 2011, Hawkings had participated in a trial of a new headband-styled device called the iBrain. The device is designed to "read" the wearer's thoughts by picking up "waves of electrical brain signals," which are then interpreted by a special algorithm, according to an article in The New York Times . This device could be a revolutionary aid to people with ALS.

Hawking on AI

In 2014, Hawking, among other top scientists, spoke out about the possible dangers of artificial intelligence, or AI, calling for more research to be done on all of possible ramifications of AI. Their comments were inspired by the Johnny Depp film Transcendence , which features a clash between humanity and technology.

"Success in creating AI would be the biggest event in human history," the scientists wrote. "Unfortunately, it might also be the last, unless we learn how to avoid the risks." The group warned of a time when this technology would be "outsmarting financial markets, out-inventing human researchers, out-manipulating human leaders, and developing weapons we cannot even understand."

Hawking reiterated this stance while speaking at a technology conference in Lisbon, Portugal, in November 2017. Noting how AI could potentially make gains in wiping out poverty and disease, but could also lead to such theoretically destructive actions as the development of autonomous weapons, he said, "We cannot know if we will be infinitely helped by AI, or ignored by it and sidelined, or conceivably destroyed by it."

Hawking and Aliens

In July 2015, Hawking held a news conference in London to announce the launch of a project called Breakthrough Listen. Funded by Russian entrepreneur Yuri Milner, Breakthrough Listen was created to devote more resources to the discovery of extraterrestrial life.

Breaking the Internet

In October 2017, Cambridge University posted Hawking's 1965 doctoral thesis, "Properties of Expanding Universes," to its website. An overwhelming demand for access promptly crashed the university server, though the document still fielded a staggering 60,000 views before the end of its first day online.

When Did Stephen Hawking Die?

On March 14, 2018, Hawking finally died of ALS, the disease that was supposed to have killed him more than 50 years earlier. A family spokesman confirmed that the iconic scientist died at his home in Cambridge, England.

The news touched many in his field and beyond. Fellow theoretical physicist and author Lawrence Krauss tweeted: "A star just went out in the cosmos. We have lost an amazing human being. Hawking fought and tamed the cosmos bravely for 76 years and taught us all something important about what it truly means to celebrate about being human."

Hawking's children followed with a statement: "We are deeply saddened that our beloved father passed away today. He was a great scientist and an extraordinary man whose work and legacy will live on for many years. His courage and persistence with his brilliance and humor inspired people across the world. He once said, 'It would not be much of a universe if it wasn’t home to the people you love.' We will miss him forever."

Later in the month, it was announced that Hawking's ashes would be interred at Westminster Abbey in London, alongside other scientific luminaries like Isaac Newton and Charles Darwin .

On May 2, 2018, his final paper, titled "A smooth exit from eternal inflation?" was published in the Journal of High Energy Physics . Submitted 10 days before his death, the new report, co-authored by Belgian physicist Thomas Hertog, disputes the idea that the universe will continue to expand.

QUICK FACTS

- Name: Stephen Hawking

- Birth Year: 1942

- Birth date: January 8, 1942

- Birth City: Oxford, England

- Birth Country: United Kingdom

- Gender: Male

- Best Known For: Stephen Hawking was a scientist known for his work with black holes and relativity, and the author of popular science books like 'A Brief History of Time.'

- Science and Medicine

- Astrological Sign: Capricorn

- University of Cambridge

- Gonville & Caius College

- Oxford University

- California Institute of Technology

- Interesting Facts

- As an author, Stephen Hawking was best known for his best seller 'A Brief History of Time.'

- At the age of 21, Stephen Hawking was diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS, or Lou Gehrig's disease).

- Death Year: 2018

- Death date: March 14, 2018

- Death City: Cambridge, England

- Death Country: United Kingdom

We strive for accuracy and fairness. If you see something that doesn't look right , contact us !

- My goal is simple. It is a complete understanding of the universe, why it is as it is and why it exists at all.

- Not only does God definitely play dice, but He sometimes confuses us by throwing them where they can't be seen.

- Intelligence is the ability to adapt to change.

- Before my condition was diagnosed, I had been very bored with life. There had not seemed to be anything worth doing.

- I believe that life on Earth is at an ever increasing risk of being wiped out by a disaster such as sudden global warming, nuclear war, a genetically engineered virus, or other dangers. I think the human race has no future if it doesn't go into space.

- Because there is a law such as gravity, the universe can and will create itself from nothing. Spontaneous creation is the reason there is something rather than nothing, why the universe exists, why we exist.

- It is not necessary to invoke God to light the blue touch paper and set the universe going.

- It is not clear that intelligence has any long-term survival value.

- If, like me, you have looked at the stars, and tried to make sense of what you see, you too have started to wonder what makes the universe exist.

- I regard the brain as a computer which will stop working when its components fail. There is no heaven or afterlife for broken down computers; that is a fairy story for people afraid of the dark.

- Science is beautiful when it makes simple explanations of phenomena or connections between different observations. Examples include the double helix in biology, and the fundamental equations of physics.

- People who boast about their I.Q. are losers.

- We shouldn't be surprised that conditions in the universe are suitable for life, but this is not evidence that the universe was designed to allow for life. We could call order by the name of God, but it would be an impersonal God. There's not much personal about the laws of physics.

Famous British People

Mick Jagger

Agatha Christie

Alexander McQueen

The Real Royal Scheme Depicted in ‘Mary & George’

William Shakespeare

Anya Taylor-Joy

Kate Middleton, Princess of Wales

Kensington Palace Shares an Update on Kate

Prince William

Where in the World Is Kate Middleton?

Help | Advanced Search

Physics > History and Philosophy of Physics

Title: stephen hawking (1942-2018), towards a complete understanding of the universe.

Abstract: Two of the major achievements of Stephen Hawking are described in elementary terms. They are his work on the beginning of the universe and his work on the end of black holes. These are perhaps the scientific achievements for which he is best known. Some of the qualities that enabled his great achievements are also described. The article is a slightly edited version of one solicited by the Proceedings of the (US) National Academy of Sciences for their Retrospectives section and will appear there.

Submission history

Access paper:.

- Other Formats

References & Citations

- INSPIRE HEP

- Google Scholar

- Semantic Scholar

BibTeX formatted citation

Bibliographic and Citation Tools

Code, data and media associated with this article, recommenders and search tools.

- Institution

arXivLabs: experimental projects with community collaborators

arXivLabs is a framework that allows collaborators to develop and share new arXiv features directly on our website.

Both individuals and organizations that work with arXivLabs have embraced and accepted our values of openness, community, excellence, and user data privacy. arXiv is committed to these values and only works with partners that adhere to them.

Have an idea for a project that will add value for arXiv's community? Learn more about arXivLabs .

Stephen Hawking’s final paper predicted the end of the world and revealed a parallel universe

STEPHEN Hawking submitted a research paper just weeks before he died hinting how scientists could find another universe.

Bright blue meteor stuns millions

‘Devil comet’ to wow Aussies this weekend

‘Moon is made of gas’: Embarrassing fail

PROFESSOR Stephen Hawking submitted a research paper just two weeks before he died hinting how scientists could find another universe and predicting the end of the world.

The iconic physicist completed the groundbreaking research from his deathbed, said co-author professor Thomas Hertog.

It sets out the maths needed for a Star Trek-style space probe to find experimental evidence for the existence of a “multiverse” — the idea our cosmos is only one of many universes.

If such evidence had been found while he was alive, it might have put Hawking in line for the Nobel prize he had so desired, reports The Sunday Times.

“This was Stephen: to boldly go where Star Trek fears to tread,” said Hertog, professor of theoretical physics at KU Leuven University in Belgium.

“He has often been nominated for the Nobel and should have won it. Now he never can.”

REVEALED: Surprising things Stephen Hawking taught us

MORE: Stephen Hawking’s death shocks the world

The paper confronts an issue that had bothered Hawking since the 1983 “no-boundary” theory he devised with James Hartle.

In his “no boundary theory” devised with James Hartle, the pair described how the Earth hurtled into existence during the Big Bang.

But the theory also predicted a multiverse meaning the phenomenon was accompanied by a number of other “Big Bangs” creating separate universes.