Module 16: The Origins of Public Speaking

Ancient greece, the rise of democracy.

“Biblioteca” by queulat00. CC-BY .

In order to understand what contemporary public speaking is, we first must understand the genesis of public speaking. We begin with the Greeks and rhetoric. Rhetoric , as defined by Aristotle, is the “faculty of discovering in the particular case all the available means of persuasion.” [1] For the Greeks, rhetoric, or the art of public speaking, was first and foremost a means to persuade. Greek society relied on oral expression, which also included the ability to inform and give speeches of praise, known then as epideictic (to praise or blame someone) speeches. The ability to practice rhetoric in a public forum was a direct result of generations of change in the governing structures of Attica (a peninsula jutting into the Aegean Sea), with the city of Athens located at its center. The citizens of Athens were known as Athenians, and were among the most prosperous of people in the Mediterranean region.

Speech is the mirror of action. – Solon

It was in the Homeric Period, also known as “The Age of Homer,” between 850 B.C. and 650 B.C., that an evolution in forms of government from monarchy to oligarchy, and tyranny to eventual democracy, began in ancient Greece. Homer was the major figure of ancient Greek literature and the author of the earliest epic poems, the Iliad and the Odyssey. In the year 630 B.C., the last tyrant of Attica, Ceylon, seized the Acropolis, which was the seat of government in Athens, and established himself as the ruler of all Attica. He didn’t rule for long. Ceylon was overthrown within weeks by farmers and heavily armed foot soldiers known as hoplites. Many of Ceylon’s followers were killed, and the few that escaped death fled into the mountains. Thus, Athenian democracy was born.

In 621 B.C., the citizens of Athens commissioned Draco , who was an elder citizen considered to be the wisest of the Greeks, to sort their laws into an organized system known as codification, because until that time, they simply remained an oral form of custom and tradition and weren’t written like the laws of today. Draco was concerned only with criminal offenses, which until this time had been settled through blood feud (an eye-for-an-eye type of revenge between families) or rulings by the King. Draco established courts, complete with juries, to hear cases of homicide, assault, and robbery. By conforming the codes for criminal offenses into standards of practice, Draco began the tradition of law, where cases were decided on clearly enunciated crimes and penalties determined by statute rather than by the whims of the nobility. His laws helped constitute a surge in Athenian democracy.

In 593 B.C. Draco’s laws were reformed by Solon, an Athenian legislator, who introduced the first form of popular democracy into Athens. Solon’s courts became the model for the Romans and centuries later for England and America. Murphy and Katula argued: “It is with Solon’s reforms that we mark the unalterable impulse toward popular government in western civilization.” [2] The Athenian period of democratization included legislative as well as judicial reform.

It was during the reign of Pericles , from 461 B.C. to 429 B.C., that Athens achieved its greatest glory. Some of these accomplishments included the installation of a pure democracy to maintain, a liberalized judicial system to include poor citizens so that they could serve on juries, and the establishment of a popular legislative assembly to review annually all laws. In addition, he established the right for any Athenian citizen to propose or oppose a law during assembly. Pericles’ achievements far exceeded those mentioned. Because of his efforts, Athens became the crossroads of the world—the center of western civilization—and with it came the need for public speaking.

“Discurso Funebre Pericles” by Philipp Foltz. Public domain.

“Persuasion is the civilized substitute for harsh authority and ruthless force,” wrote R.T. Oliver. [3] Oliver said that the recipients of any persuasive discourse must feel free to make a choice. In a free society it is persuasion that decides rules, determines behavior,and acts as the governing agent in human physical and mental activities. In every free society individuals are continuously attempting to change the thoughts and/or actions of others. It is a fundamental concept of a free society. Ian Harvey suggested that the technique of persuasion is the technique of persuading free people to a pattern of life; and persuasion is the only possible means of combining freedom and order. [4] That combination successfully achieved is the solution to the overriding problems of our time. Rhetoric (persuasion), public speaking and democracy are inextricable. As long as there is rhetoric, and public speaking to deliver that message, there will exist democracy; and as long as there is democracy, there will exist rhetoric and public speaking.

I believe that the will of the people is resolved by a strong leadership. Even in a democratic society, events depend on a strong leadership with a strong power of persuasion, and not on the opinion of the masses. – Yitzhak Shamir

The Nature of Rhetoric

“Socrates” by Coyau. Coyau / Wikimedia Commons / CC-BY-SA-3.0 .

Pericles’ democracy established the need for training in public speaking. Greek assemblies debated old and new laws on a yearly basis. The courtrooms that Solon reformed now bristled with litigation. Pericles’ juries numbered between 500 and 2,000 people, so speaking at a public trial was similar to speaking at a public meeting. And to speak at a legislative assembly required serious, highly developed, and refined debate, because at stake generally were issues of peace and war. Murphy and Katula stated that the Athenian citizens realized that their very future often depended on their ability to speak persuasively. [5] Public speaking was an Olympic event where the winner received an olive wreath and was paraded through his town like a hero. Thus, Athens became a city of words, a city dominated by the orator. Athens witnessed the birth of what we know today as rhetoric .

To say that rhetoric played an important role in Greek and Roman life would be an understatement. The significance of rhetoric and oratory was evident in Greek and Roman education. George Kennedy [6] noted that rhetoric played the central role in ancient education. At about the age of fourteen, (only) boys were sent to the school of the rhetorician for theoretical instruction in public speaking, which was an important part of the teaching of the sophists. Public speaking was basic to the educational system of Isocrates (the most famous of the sophists); and it was even taught by Aristotle.” [7]

Dialectics and Logic

It is important to note that rhetoric and oratory are not the same, although we use rhetoric and oratory synonymously; nor are rhetoric and dialectic the same. Zeno of Elea (5th century B.C.), a Greek mathematician and philosopher of the Eleatic school, is considered to be the inventor of dialectical reasoning. However, it is Plato, another Greek philosopher and teacher of Aristotle, and not Socrates, that we attribute the popularity of dialectical reasoning. Dialectic can be defined as a debate intended to resolve a conflict between two contradictory (or polar opposites), or apparently contradictory ideas or elements logically, establishing truths on both sides rather than disproving one argument. Both rhetoric and dialectic are forms of critical analysis.

Among the most significant thinkers of the fifth century B.C. were the traveling lecturers known as sophists . They were primarily teachers of political excellence who dealt with practical and immediate issues of the day, and whose investigations led in many instances to a philosophical relativism . Unlike Socrates and Plato, the sophists believed that absolute truth was unknowable and perhaps nonexistent, especially in the sphere of forensics and political life, where no universal principles could be accepted. Courses of action had to be presented in persuasive fashion. Unlike the sophists, Socrates taught that truth was absolute and knowable and that a clear distinction should be made between dialectic, the question and answer method of obtaining the one correct answer, and rhetoric, which does not seem interested in the universal validity of the answer but only in its persuasiveness for the moment. Plato developed this criticism of rhetoric to such an extent that he is the most famous and most thorough-going of the enemies of rhetoric. Plato preferred the philosophical method of formal inquiry known as dialectic .

In making a speech one must study three points: first, the means of producing persuasion; second, the language; third, the proper arrangement of the various parts of the speech. – Aristotle

The Rhetorical Approach

“The School of Athens” by Raphael. Public domain.

Aristotle wrote that rhetoric is the faculty of discovering in the particular case all the available means of persuasion. He cited four uses of rhetoric: (1) by it truth and justice maintain their natural superiority; (2) it is suited to popular audiences, since they cannot follow scientific demonstration; (3) it teaches us to see both sides of an issue, and to refute unfair arguments; and (4) it is a means of self-defense. For Aristotle, rhetoric is the process of developing a persuasive argument, and oratory is the process of delivering that argument. He stated that the “authors of ‘Arts of Speaking’ have built up but a small portion of the art of rhetoric; because this art consists of proofs alone—all else is but accessory. Yet these writers say nothing of enthymemes, the very body and substance of persuasion.” [8]

Aristotle said that rhetoric has no special subject-matter; that is, it isn’t limited to particular topics and nothing else. He claimed that certain forms of persuasion come from outside and do not belong to the art itself. This refers to, for example, witnesses, forced confessions, and contracts that Aristotle said are external to the art of speaking. He considered these to be non-artistic proofs. Aristotle identified what he considered to be artistic proofs which must be supplied by the speaker’s invention (the “faculty of discovering” that Aristotle used in his definition of rhetoric); and these artistic means of persuasion are threefold. They consist in (1) evincing through the speech a personal character that will win the confidence of the listener; (2) engaging the listener’s emotions; and (3) proving a truth, real or apparent, by argument. Aristotle concluded that the mastery of the art, then, called for (1) the power of logical reasoning (logos); a knowledge of character (ethos); and a knowledge of the emotions (pathos).

In summary, Plato had opposed rhetoric to dialectic; Aristotle compared the two: both have to do with things which are within the field of knowledge of all men and are not part of any specialized science. They do not differ in nature, but in subject and form: dialectic is primarily philosophical, rhetoric political; dialectic consists of question and answer, rhetoric of a set speech. Both can be reduced to a system and thus are properly called “art.”

Rhetoric is the art of ruling the minds of men. – Plato

Aristotle became the primary source of all later rhetorical theory. Eventually, the dispute between rhetoric and philosophy in the time of Aristotle had ended in a compromise in which philosophy accepted rhetoric as a means to a goal. The rhetoric of not only Cicero and Quintilian, but of the Middle Ages, of the Renaissance, and of modern times, is basically Aristotelian.

- Kennedy, G. (1963). The Art of Persuasion in Greece . Princeton: University Press. p. 19 ↵

- Murphy James J. and Katula, R.A. (1995). A Synoptic History of Classical Rhetoric . 2nd ed. Davis: Ca. Hermagoras Press. ↵

- Oliver, R.T. (1950). Persuasive Speaking . New York: Longmans, Green and Co. p.1 ↵

- Harvey, I. (1951). The Technique of Persuasion. London: The Falcon Press. ↵

- Murphy and Katula 1995 ↵

- Kennedy, G. (1963). The Art of Persuasion in Greece . Princeton: University Press. ↵

- Kennedy 1963, p. 7 ↵

- (Book 1, p. 1) ↵

- Chapter 2 Ancient Greece. Authored by : Peter A. DeCaro, Ph.D.. Provided by : University of Alaska, Fairbanks, AK. Located at : http://publicspeakingproject.org/psvirtualtext.html . Project : The Public Speaking Project. License : CC BY-NC-ND: Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives

- 475_efeso_biblioteca_celso. Authored by : queulat00. Located at : https://flic.kr/p/axRstZ . License : CC BY: Attribution

- Parc de Versailles, Rond-Point des Philosophes, Isocrate, Pierre Granier MR1870 04. Authored by : Coyau. Located at : http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Parc_de_Versailles,_Rond-Point_des_Philosophes,_Isocrate,_Pierre_Granier_MR1870_04.jpg . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Discurso funebre pericles. Authored by : Philipp Foltz. Located at : http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Discurso_funebre_pericles.PNG . License : Public Domain: No Known Copyright

- Sanzio 01 Plato Aristotle. Authored by : Raphael. Provided by : Web Gallery of Art. Located at : http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Sanzio_01_Plato_Aristotle.jpg . License : Public Domain: No Known Copyright

Privacy Policy

Learn How to Speak Basic Greek

Overview of the parts of speech in the greek language.

Written by Greek Boston in Learn How to Speak Basic Greek Comments Off on Overview of the Parts of Speech in the Greek Language

According to Webster’s Dictionary, a noun is:

any member of a class of words that typically can be combined with determiners to serve as the subject of a verb, can be interpreted as singular or plural, can be replaced with a pronoun, and refer to an entity, quality, state, action, or concept

Nouns are an important part of any Greek sentence. They can change form depending on which case they are in the sentence (such as nominative or accusative). In the following examples, the nouns are boldfaced:

- Το σκυλί έφαγε ένα κόκκαλο . To skili efage ena kokkalo . The dog ate a bone .

- Η γάτα έπινε γάλα . – I gata pane gala . The cat drank milk .

- Το αυτοκίνητο έχει κόκκινα καθίσματα . To aftokinito ehee kokkina kathismata . The car has red seats.

According to Webster’s Dictionary , a pronoun is:

any of a small set of words in a language that are used as substitutes for nouns or noun phrases and whose referents are named or understood in the context

In the Greek language, these are the main pronouns:

- I – Εγώ – ego

- You – εσύ – esi

- He – αυτός – aftos

- She – αυτή – afti

- It – αυτό – afto

- We – εμείς – emees

- You – εσείς – esees

- They – αυτοί – afti

According to Webster’s Dictionary, an adjective is:

a word belonging to one of the major form classes in any of numerous languages and typically serving as a modifier of a noun to denote a quality of the thing named, to indicate its quantity or extent, or to specify a thing as distinct from something else

Adjectives are also very common in the Greek language. In the following examples, the adjectives are boldfaced:

- Το κόκκινο αυτοκίνητο έχει καινούργιες θέσεις. To kokkino aftokinito ehee kenooryies Το κόκκινο αυτοκίνητο έχει καινούργιες θέσεις. thesees. The red car has new seats.

- Το κορίτσι είναι μικρό . To koritsi eenai mikro. The girl is little .

- Η γλυκιά ζύμη έχει ένα υπέροχο σιρόπι. I glikia zimi ehee ena uperoho siropi. The sweet pastry has a delicious syrup.

Verbs are an important component of every sentence because it indicates an action done by the subject. In the sentence, “She runs” the subject is “she” and the verb is “runs”. Verbs work the same way in the Greek language. Here’s a more in depth definition from Webster’s Dictionary:

a word that characteristically is the grammatical center of a predicate and expresses an act, occurrence, or mode of being, that in various languages is inflected for agreement with the subject, for tense, for voice, for mood, or for aspect, and that typically has rather full descriptive meaning and characterizing quality but is sometimes nearly devoid of these especially when used as an auxiliary or linking verb

In the following examples, the verbs are boldfaced:

- Το κορίτσι περπατά πολύ γρήγορα. to koritsi perpata poli grigora. The girl walks very fast.

- Το βιβλίο είναι ασφαλές εδώ. To vivlio eenai asfales etho. The book is safe here.

- Αγόρασα ένα νέο φόρεμα. Agorasa ena Neo forema. I bought a new dress.

According to Webster’s Dictionary, an adverb is:

a word belonging to one of the major form classes in any of numerous languages, typically serving as a modifier of a verb, an adjective, another adverb, a preposition, a phrase, a clause, or a sentence, expressing some relation of manner or quality, place, time, degree, number, cause, opposition, affirmation, or denial, and in English also serving to connect and to express comment on clause content

Adverbs work the same way in Greek as they do in the English language. In the following examples, the adverbs are boldfaced:

- Το παγωτό ήταν εξαιρετικά κρύο. To pagoto itan exepetika kruo. The ice cream was extremely cold.

- Το βιβλίο είναι αρκετά συναρπαστικό. To vivlio einai arketa sunarpastiko. The book is quite fascinating.

- Περπατά πολύ γρήγορα. Perpata poli grygora. She walks very fast.

Prepositions

According to Webster’s Dictionary , prepositions are:

a function word that typically combines with a noun phrase to form a phrase which usually expresses a modification or predication

They also work in much the same way in English as they do in Greek. In the following examples, the prepositions are boldfaced:

- Το βιβλίο είναι πάνω στο τραπέζι. To vivlio eenai pano sto trapezi. The book is on the table.

- Η γάτα είναι κάτω από την καρέκλα. I gata eenai kato apo tin karekla. The cat is under the chair.

- Το αγόρι είναι με τη μητέρα. To agori eenai me ti mitera. The boy is with the mother.

As with learning anything in Greek, it is important to familiarize yourself with these concepts. With repeat exposure through practice, they will become more ingrained.

The Learn Greek section on GreekBoston.com was written by Greeks to help people understand the conversational basics of the Greek language. This article is not a substitute for a professional Greek learning program, but a helpful resource for people wanting to learn simple communication in Greek.

Categorized in: Learn How to Speak Basic Greek

This post was written by Greek Boston

Share this Article:

Read Other Articles About How to Learn Basic Greek:

Greek Scenery Vocabulary Words

Ways to Learn Colloquial Greek

Conjugating the Verb to Have in Greek in the Present Tense

Learn How to Be Polite When Speaking Greek

Greek text to speech

Easily convert text to speech in Greek, and 90 more languages. Try our Greek text to speech free online. No registration required. Create Audio

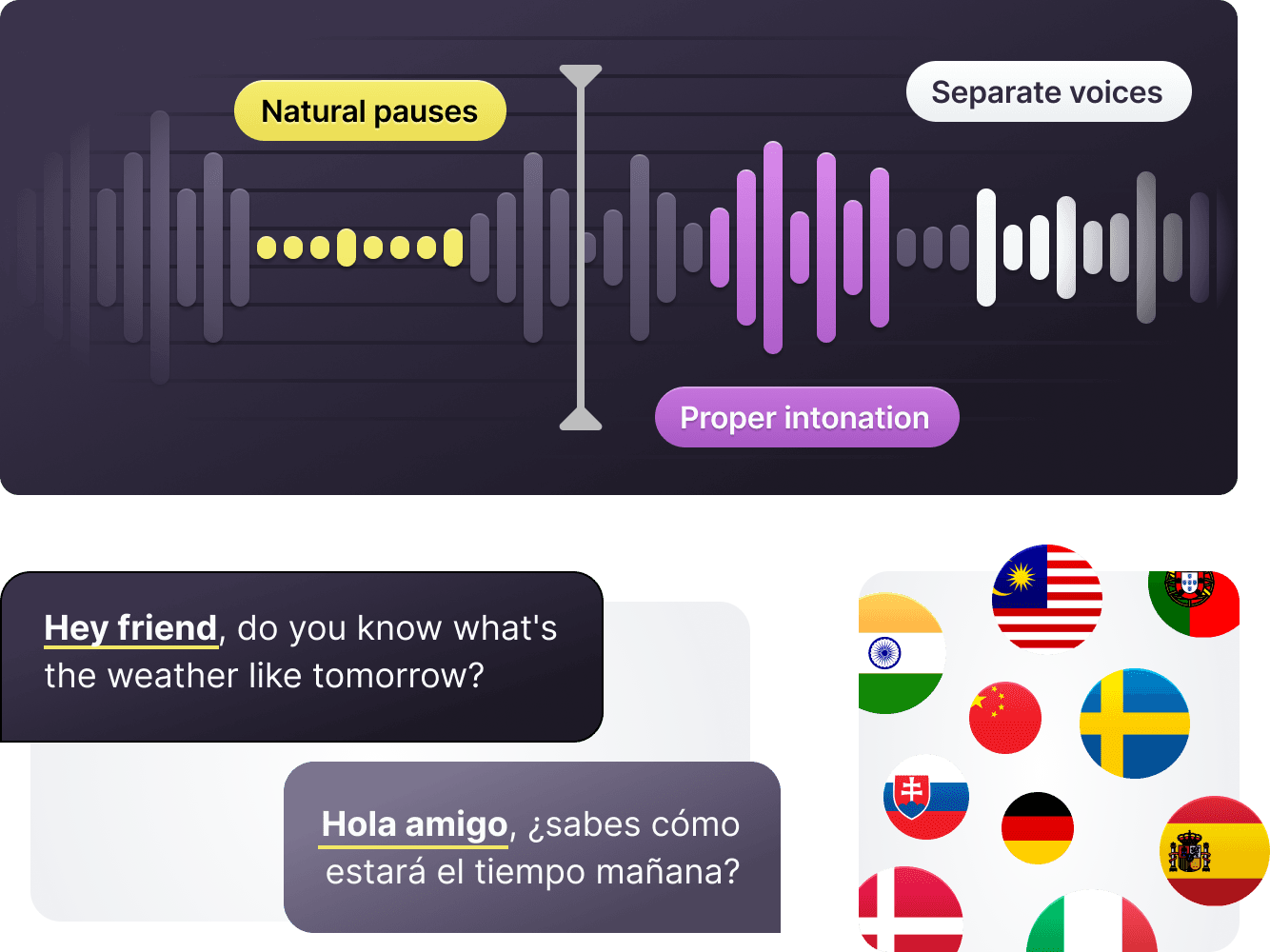

Greek text to speech online voices make it easy to create audio guides, videos and language lessons in Greek. Turn a Word document to MP3 using Greek text to speech and download it instantly, or convert a Powerpoint presentation to a Greek voice video in minutes. Narakeet makes it easy to create Greek voiceover for your promotional materials, without having to hire Greek voice talent or record the audio yourself. Our text to speech Greek software does all the hard work.

Text to voice Greek generators provided by Narakeet are based on latest neural-network AI technologies. They create natural, life-like realistic online text to speech Greek voices.

Get started with text to speech Greek free – check out the instructions below:

Narakeet has 3 Greek text to speech male and female voices. Play the video below (with sound) for a quick demo.

Text to speech Greek voices

In addition to these voices, Narakeet has 700 text-to-speech voices in 90 languages .

For more options (uploading Word documents, voice speed/volume controls, working with Powerpoint files or Markdown scripts), check out our Tools .

Greek voice over

Text to speech Greek online voices are a great way to record audio materials and videos, much faster and more conveniently than hiring Greek voice talent. Here are some things you can make with Narakeet text reader Greek:

- Greek voice overs

- Greek TTS audio clips

- Text to speech Greek online blog versions

- Text to voice Greek social media stories

- Text to speech online Greek voice messages

- TTS Greek MP3 files

- Speech in greek from Word documents

Greek accent generator

In addition to Greek voice overs, you can use our text to speech Greek online voices to create English audio in Green accent, as if a person from Greece was reading the text. To do that, just select one of the Greek TTS voices, but type or upload English text.

Narakeet helps you create text to speech voiceovers , turn Powerpoint presentations and Markdown scripts into engaging videos. It is under active development, so things change frequently. Keep up to date: RSS , Slack , Twitter , YouTube , Facebook , Instagram , TikTok

Koine-Greek

Parts-of-speech & morphosyntax, part i: parts-of-speech and morphosyntax, 1. verbal inflectional categories, 1.1 valance & valency alternating morphology, 1.1.1 transitivity and embodiment 1.1.2 prototypical transitive events 1.1.3 event energy source 1.1.4 event energy direction 1.1.5 notes on activa tantum and media tantum verbs, 1.2.1 perfective 1.2.2 imperfective 1.2.3 completive-resultative, 1.3.1 past 1.3.2 non-past 1.3.3 future, 1.4 mood/modality, 1.4.1 indicative: the unmarked/default mood 1.4.2 subjunctive: epistemic modality 1.4.3 optative: remote epistemic modality 1.4.4 imperative: deontic modality & illocutionary force 1.4.5 exhortatives: interlocutors & participant reference, 1.5 subject agreement, 1.5.1 person 1.5.2 number, 2. inflectional morphology of the verb, 3. auxiliary verbs, 3.1 types of auxiliaries 3.2 periphrasis 3.3 auxiliaries and participles, 4. verbal derivational morphology, 4.1 infinitive 4.2 participle 4.3 compounding & similar processes, 4.3.1 pre-verb attachment/directionals 4.3.2 compounding 4.3.3 noun incorporation, 5. nominal inflectional categories, 5.1.1 gender as noun class 5.1.2 masculine 5.1.3 feminine 5.1.4 neuter 5.1.5 gender in nouns 5.1.6 gender agreement & co-indexing, 5.2.1 singular 5.2.2 plural 5.2.3 dual*, 6. inflectional morphology of the noun, 7. inflectional morphology of the adjective, 7.1 adjective inflection classes and iconicity 7.2 formal relationships among adjective classes, 8. inflectional morphology of quantifiers, 9. other derivational morphology, 9.1 nominalization 9.2 modifier derivation, 10. referential & deictic system, 10.1 interlocutives, 10.1.1 personal pronouns 10.1.2 possessive pronouns 10.1.3 reflexive pronouns, 10.2 non-interlocutives, 10.2.1 definite, 10.2.1.1 substitutive, 10.2.1.1.1 personal 10.2.1.1.2 demonstrative, 10.2.1.2 non-substitutive, 10.2.2 non-definite, 10.2.2.1 indefinite 10.2.2.2 interrogative, 10.2.3 relative 10.2.4 correlative, 11. prepositions, 12. other lexical classes, 12.1 adverbs 12.2 negators 12.3 connectives 12.4 interjectives.

Begin typing your search above and press return to search. Press Esc to cancel.

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

Free Speech in Ancient Greece

Learn about how the ancient Greeks viewed free speech.

Geography, Human Geography, Social Studies, World History

The ancient Greeks were pioneers of free speech. Their theater, literature, and educational institutions explored the human experience, freedom of expression, and questioning of authority.

Like contemporary societies, however, ancient Greece did not allow complete freedom of speech . Leaders, philosophers, artists, and everyday citizens wrestled with balancing individual freedom and public order.

Articles & Profiles

Instructional links, media credits.

The audio, illustrations, photos, and videos are credited beneath the media asset, except for promotional images, which generally link to another page that contains the media credit. The Rights Holder for media is the person or group credited.

Last Updated

October 19, 2023

User Permissions

For information on user permissions, please read our Terms of Service. If you have questions about how to cite anything on our website in your project or classroom presentation, please contact your teacher. They will best know the preferred format. When you reach out to them, you will need the page title, URL, and the date you accessed the resource.

If a media asset is downloadable, a download button appears in the corner of the media viewer. If no button appears, you cannot download or save the media.

Text on this page is printable and can be used according to our Terms of Service .

Interactives

Any interactives on this page can only be played while you are visiting our website. You cannot download interactives.

Related Resources

What is "Speech" in Greek and how to say it?

Learn the word in this minigame:, more media vocabulary in greek, example sentences, how to say "speech" in greek and in 45 more languages., other interesting topics in greek, ready to learn greek, language drops is a fun, visual language learning app. learn greek free today..

- Drops for Business

- Visual Dictionary (Word Drops)

- Recommended Resources

- Redeem Gift

- Join Our Translator Team

- Help and FAQ

Drops Courses

bottom_desktop desktop:[300x250]

– An Open Forum for Classics

Two Concepts of Free Speech, from Classical Athens to Today’s Campus

James Kierstead

As the Oxford political theorist Teresa Bejan reminded us a few years ago now in The Atlantic , the Greeks had two concepts of free speech . The first, isēgoriā (ἰσηγορία) could more literally be translated ‘equality of public speech’, whereas the second, parrhēsiā (παρρησία), is more directly focussed on the license to say whatever you want: the prefix comes from pās (πᾶς), ‘all’ or ‘everything’, so that parrhēsiā is,at root, the freedom to say anything.

Bejan argued that we risk misunderstanding today’s deplatformers and anti-free-speech campaigners unless we realize that they’re more concerned about isēgoriā than parrhēsiā. “What they care about,” writes Bejan, “is the equal right to speech, and equal access to a public forum in which the historically marginalized and excluded can be heard and count equally with the privileged.” Bejan thinks that a convincing defence of parrhēsiā on college campuses can and should be mounted, but only if we reconnect with the egalitarianism that she thinks undergirds both isēgoriā and parrhēsiā .

I’m basically in agreement with Bejan on this – that “the alternative” to defending expressive liberty “is to allow the powers-that-happen-to-be to grant that liberty as a license to some individuals while denying it to others.” But I also think there’s more that we can get out of the Classical Greeks’ two concepts of free speech, especially if we go back to the world they emerged from and examine the ways in which they were used and the spaces they were associated with. Once we do that, we should be in a position to develop a more nuanced conception of which types of speech norms should be encouraged or defended in different contexts. Isēgoriā , I will argue, does have its claims in certain spaces, and it does make sense to encourage it in the seminar room in particular. But it’s parrhēsiā that we will ultimately need to defend if we want to keep free speech alive, within the academy and in society as a whole.

Even before Athens’ Classical democracy was up and running, parrhēsiā and isēgoriā had emerged from slightly different contexts. Parrhēsiā was particularly associated with a tradition of satirical poetry written in iambs and often aimed at tyrants , the sole rulers who came to power in a clutch of city-states across the Greek world in the 6 th century BC. Isēgoriā , by contrast, had long been associated with formal political bodies such as assemblies and councils, and with the ability of every man who qualified for them to have his say on the affairs of the polis (πόλις, city-state) on an equal basis with his peers.

These historical differences carried on into the Classical period, with the two values always being associated with slightly different spaces and institutions. According to his student Plato, Socrates expressed puzzlement about why the Athenians only listened to experts when it came to things like ship-building, but were willing to listen to any man – including poor and low-born men such as shoe-makers and carpenters – when it came to making decisions about the direction of the city-state. Demosthenes stresses that it’s in the Athenians’ own interest to listen to everyone who wants to offer advice, because that will mean they have a variety of proposals to choose from. Both of these passages show the importance that the ideal of equal public speech – isēgoriā – had in the Assembly, the most important decision-making body in democratic Athens.

P arrhēsiā , for its part, was more likely to be found as part of ordinary social life: the philosopher and orator Isocrates, for instance, describes it as having an important part to play in education, since it allows the sort of honest feedback from acquaintances which can help a man improve himself. Unlike isēgoriā , parrhēsiā didn’t really flourish in the formal political institutions that ran the democratic city-state; but it did flourish in the theatre, especially the comic theatre.

That the comic theatre was a place where parrhēsiā thrived is something we hear from the ancient sources themselves. Isocrates complains (almost certainly inaccurately) that, even though Athens is a democracy, there is no parrhēsiā except “here in the assembly – for the most moronic and narcissistic people – and in the theatre for producers of comedy.” The legal speech-writer Lysias describes the defendant in one case as doing things that are too shameful to mention – “although you hear of them from the comic poets every year” ( Fragment 53 ). And in the ideal city of Plato’s Laws , comedy is regulated in order to keep kakēgoriā (‘bad public speech’) under control.

Nobody who’s seen or read the plays of Aristophanes will be surprised at this association between comedy and unhindered, sometimes even offensive, free speech. His eleven surviving plays – the only complete examples we have of the hard-hitting, no-holds-barred genre of ‘Old Comedy’ – are brimming with obscenities, both scatological and sexual. Actors wore an exaggerated paunch and an outsized phallus as part of their costumes, and acted out defecation and sexual acts on stage. Characters shifted from mock-tragic at one moment to broadly orgiastic the next, creating an effect that probably has its closest modern analogy in fast-moving, nothing-is-off-limits cartoons like South Park or Family Guy . And the plots can be similarly outlandish – a farmer who’s had enough of the Peloponnesian War drawing up his own private peace-treaty with Sparta ( Acharnians ); women bringing the war to an end through a coordinated sex-strike ( Lysistrata ); a man flying to the abode of the gods on a giant dung beetle ( Peace ).

Aristophanes’ plays were also bracingly political – here the modern analogy would be something like John Oliver’s or Bill Maher’s shows, though Aristophanes can be even more hard-hitting (and considerably more offensive). In a few passages where he seems to address his audience directly, Aristophanes appears to defend himself, claiming that what he was doing was helpful to the democracy he lived in. We don’t know exactly what the Athenians thought about that; but they didn’t seem to have any trouble with bawdy satire having a prominent place in their public culture. The Festival of Dionysus was, after all, a major civic and religious event, and a centrepiece of the Athenian festival calendar.

Why was this sort of unhindered free speech seen as salutary in democratic Athenian society? Perhaps because parrhēsiā , as a character in Euripides’ Suppliants implies , allowed the weaker members of society to have their say, permitting them to push back and hold their own against wealthier and more powerful citizens, if only every now and then. But parrhēsiā didn’t just help people lower down on the social hierarchy speak up against their supposed betters. It also allowed intellectuals to speak up against the reigning orthodoxies of the day. Socrates in Plato’s dialogue Gorgias , for example, encourages one of his interlocutors to speak frankly , adding that he is “clearly saying things now which others think, but don’t want to say out loud.” And Aristotle describes the “great-souled man” as “ a frank speaker ” ( parrhēsiastēs ), since “hiding things is characteristic of people who are afraid, and who care less for the truth than for opinion.”

These, then, were the Greeks’ two concepts of free speech, and what came to seem their natural habitats: isēgoriā , or equality of public speech, which was associated with formal political institutions and democratic deliberation; and parrhēsiā , the license to say anything, even (or especially) if it went against the current, which had its stronghold in the ribald comic theatre of playwrights like Aristophanes. Nobody would argue that the Athenians lived up to these ideals perfectly, and there are ongoing scholarly controversies about what the effective limits of free speech were in Athens – which was, we should bear in mind, a more traditional and religious society than our own. But my argument here isn’t that democratic Athens was a free-speech utopia that we should emulate in every respect. Rather, it’s that the Greeks’ two concepts of free speech can help us think about the contemporary debate about free speech in universities.

In some ways, this shouldn’t seem very radical, because isēgoriā , at least, is an ideal that would find a ready home in modern discourses about free speech, at least within the academy. One of the principles most often held up by recent theorists of liberal democracy is deliberation, in the somewhat technical sense of genuinely reasoned and open discussion. In one of the most well-known versions of this ideal, Jürgen Habermas’ “ideal speech situation,” the best sort of discussion is imagined as one in which everyone is able to propose or question any idea whatsoever, without feeling intimidated or coerced by anyone else. The idea that everyone should be equally able to have a say – isēgoriā , in other words – is obviously central.

And deliberative ideals of this sort are clearly something which have a place on college campuses, especially in classes and seminars. In these contexts we might well want to try to make sure everyone taking part in a discussion has a roughly equal chance to have a say. Most academic seminars, in any case, run on a series of implicit norms that the vast majority of participants are happy to go along with. These include waiting your turn to speak; not engaging in ad hominem attacks; and trying to express criticisms politely.

These kind of seminar norms aren’t a bad thing at all. Indeed, they clearly embody isēgoriā and related deliberative values in their concern for equality and for reasoned discourse. But these values can’t be the only ones informing the way we have conversations on campuses; still less can they be the only norms we have for speech outside of universities (not least because, though we academics are sometimes liable to forget it, not every conversation is a seminar). We also need to honour the unrestricted license to express ourselves, even in a way which rubs some people up the wrong way – which the Greeks called parrhēsiā. And, in fact, it’s parrhēsiā that has to be our bedrock free speech value, both on campus and off, if we’re going to preserve everyone’s right to have their say.

Why? Because even though sometimes everyone will be in agreement that something someone said was disrespectful, that won’t always be the case. People often disagree about whether something was impolite or not; and it can be easy to perceive or present something someone has said as disrespectful even when what has really bothered you isn’t the way they’ve expressed themselves but the content of what they’ve said. In other words, claims about respect, politeness, and so on, are easily weaponized against legitimate expression; and they’re especially easily weaponized in environments like contemporary universities, where an enormous political imbalance of academic and administrative staff effectively gives one side free rein to decide what counts as offensive and what doesn’t.

I sēgoriā and its modern descendants provide us with some excellent ideals to aspire to, but, short of a few minimal and practical measures such as banning direct personal abuse, it’ll never be possible to do away completely with complaints about people being disrespectful and impolite. These kinds of claims emerge virtually inevitably from conflict, and conflict is itself an inevitable feature of doing things together with other humans, who have an irritating tendency to look at the world in different ways – and to want to express these different perspectives.

We might still want to encourage the narrower set of values associated with isēgoriā in our classes and seminars. Personally, I believe we should. But the ease with which claims about disrespect can be employed to shut others up means that they shouldn’t form the basis of disciplinary procedures; instead, we should have formal rules that defend a much more generous notion of free expression.

In a previous attempt to formulate this idea, I suggested that universities should look to encourage civility as a soft norm , but also protect free speech via hard rules (for example, against scholars being sacked for ordinary political expression). Teresa Bejan is right that both of the Ancient Greek ideals we have looked at here are, at bottom, bound up with a commitment towards free and equal speech. Not all concepts of free speech are created equal, though, and the Greeks’ two concepts of free speech are different in significant ways. Ultimately, it’s the broader, more general claims of unrestricted free speech that we will have to defend if we want to have a hope of halting the gradual erosion of our expressive freedoms in our universities and beyond.

James Kierstead is Senior Lecturer in Classics at Victoria University of Wellington and the moderator of Heterodox Classics, a Heterodox Academy community.

Further Reading

E.R. Dodds’s Sather Lectures, published as The Greeks and The Irrational (Berkeley, CA, 1951) were influential in a number of ways; most relevant here is Dodds’s claim that the Classical Athenians turned against their intellectuals under the pressures of plague and war. K.J. Dover, “The freedom of the intellectual in Greek society,” Talanta 7 (1975) 24–54 (accessible here ) surveyed the evidence for the persecution of intellectuals in Athens and concluded that much of it was late and unreliable. More recently, J. Filonik, “Athenian Impiety Trials: a Reappraisal,” Dike 16 (2013) 11–96 (accessible here ) similarly concludes that trials like that of Socrates were more the exception than the rule – which doesn’t mean, of course, that they never happened.

Jürgen Habermas’ influential theories of liberalism and democracy are dispersed throughout a large and forbiddingly difficult body of writing. For his ideas on the public sphere, start with The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere , trans. T. Burger and F. Lawrence (MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, 1989) [German original, 1962]. For his “ideal speech situation” ( Ideale Sprechsituation ) see especially “Discourse Ethics: Notes on a Program of Philosophical Justification,” in Moral Consciousness and Communicative Action, trans. C. Lenhardt and S. Weber Nicholsen (MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, 1990) [German original, 1973].

Share this article via:

One thought on “ two concepts of free speech, from classical athens to today’s campus ”.

- Pingback: Two Concepts of Free Speech, From Classical Athens to Today’s Campus

Comments are closed.

- Ancient Religion

- Competitions

- Greek Language

- Greek Literature

- Latin Language

- Latin Literature

- Material Culture

- The Classical Tradition

- The Future of Classics

- The New Naso

- Uncategorized

The Two Clashing Meanings of 'Free Speech'

Today’s campus controversies reflect a battle between two distinct conceptions of the term—what the Greeks called isegoria and parrhesia.

Little distinguishes democracy in America more sharply from Europe than the primacy—and permissiveness—of our commitment to free speech. Yet ongoing controversies at American universities suggest that free speech is becoming a partisan issue. While conservative students defend the importance of inviting controversial speakers to campus and giving offense, many self-identified liberals are engaged in increasingly disruptive, even violent, efforts to shut them down. Free speech for some, they argue, serves only to silence and exclude others. Denying hateful or historically “privileged” voices a platform is thus necessary to make equality effective, so that the marginalized and vulnerable can finally speak up—and be heard.

The reason that appeals to the First Amendment cannot decide these campus controversies is because there is a more fundamental conflict between two, very different concepts of free speech at stake. The conflict between what the ancient Greeks called isegoria , on the one hand, and parrhesia , on the other, is as old as democracy itself. Today, both terms are often translated as “freedom of speech,” but their meanings were and are importantly distinct. In ancient Athens, isegoria described the equal right of citizens to participate in public debate in the democratic assembly; parrhesia , the license to say what one pleased, how and when one pleased, and to whom.

Recommended Reading

America's Many Divides Over Free Speech

What Apple Thought the iPhone Might Look Like in 1995

The Key to Escaping the Couple-Envy Trap

When it comes to private universities, businesses, or social media, the would-be censors are our fellow-citizens, not the state. Private entities like Facebook or Twitter, not to mention Yale or Middlebury, have broad rights to regulate and exclude the speech of their members. Likewise, online mobs are made up of outraged individuals exercising their own right to speak freely. To invoke the First Amendment in such cases is not a knock-down argument, it’s a non sequitur .

John Stuart Mill argued that the chief threat to free speech in democracies was not the state, but the “social tyranny” of one’s fellow citizens. And yet today, the civil libertarians who style themselves as Mill’s inheritors have for the most part failed to refute, or even address, the arguments about free speech and equality that their opponents are making .

The two ancient concepts of free speech came to shape our modern liberal democratic notions in fascinating and forgotten ways. But more importantly, understanding that there is not one, but two concepts of freedom of speech, and that these are often in tension if not outright conflict, helps explain the frustrating shape of contemporary debates, both in the U.S. and in Europe—and why it so often feels as though we are talking past each other when it comes to the things that matter most.

Of the two ancient concepts of free speech, isegoria is the older. The term dates back to the fifth century BCE, although historians disagree as to when the democratic practice of permitting any citizen who wanted to address the assembly actually began. Despite the common translation “freedom of speech,” the Greek literally means something more like “equal speech in public.” The verb agoreuein , from which it derives, shares a root with the word agora or marketplace—that is, a public place where people, including philosophers like Socrates, would gather together and talk.

In the democracy of Athens, this idea of addressing an informal gathering in the agora carried over into the more formal setting of the ekklesia or political assembly. The herald would ask, “Who will address the assemblymen?” and then the volunteer would ascend the bema , or speaker’s platform. In theory, isegoria meant that any Athenian citizen in good standing had the right to participate in debate and try to persuade his fellow citizens. In practice, the number of participants was fairly small, limited to the practiced rhetoricians and elder statesmen seated near the front. (Disqualifying offenses included prostitution and taking bribes.)

Although Athens was not the only democracy in the ancient world, from the beginning the Athenian principle of isegoria was seen as something special. The historian Herodotus even described the form of government at Athens not as demokratia , but as isegoria itself . According to the fourth-century orator and patriot Demosthenes, the Athenian constitution was based on speeches ( politeia en logois ) and its citizens had chosen isegoria as a way of life. But for its critics, this was a bug, as well as a feature. One critic, the so-called ‘Old Oligarch,’ complained that even slaves and foreigners enjoyed isegoria at Athens, hence one could not beat them as one might elsewhere.

Critics like the Old Oligarch may have been exaggerating for comic effect, but they also had a point: as its etymology suggests, isegoria was fundamentally about equality, not freedom. As such, it would become the hallmark of Athenian democracy, which distinguished itself from the other Greek city-states not because it excluded slaves and women from citizenship (as did every society in the history of humankind until quite recently), but rather because it included the poor . Athens even took positive steps to render this equality of public speech effective by introducing pay for the poorest citizens to attend the assembly and to serve as jurors in the courts.

As a form of free speech then, isegoria was essentially political. Its competitor, parrhesia , was more expansive. Here again, the common English translation “freedom of speech” can be deceptive. The Greek means something like “all saying” and comes closer to the idea of speaking freely or “frankly.” Parrhesia thus implied openness, honesty, and the courage to tell the truth, even when it meant causing offense. The practitioner of parrhesia (or parrhesiastes ) was, quite literally, a “say-it-all.”

Parrhesia could have a political aspect. Demosthenes and other orators stressed the duty of those exercising isegoria in the assembly to speak their minds. But the concept applied more often outside of the ekklesia in more and less informal settings. In the theater, parrhesiastic playwrights like Aristophanes offended all and sundry by skewering their fellow citizens, including Socrates, by name. But the paradigmatic parrhesiastes in the ancient world were the Philosophers, self-styled “lovers of wisdom” like Socrates himself who would confront their fellow citizens in the agora and tell them whatever hard truths they least liked to hear. Among these was Diogenes the Cynic , who famously lived in a barrel, masturbated in public, and told Alexander the Great to get out of his light—all, so he said, to reveal the truth to his fellow Greeks about the arbitrariness of their customs.

The danger intrinsic in parrhesia ’s offensiveness to the powers-that-be—be they monarchs like Alexander or the democratic majority—fascinated Michel Foucault, who made it the subject of a series of lectures at Berkeley (home of the original campus Free Speech Movement) in the 1980s. Foucault noticed that the practice of parrhesia necessarily entailed an asymmetry of power, hence a “contract” between the audience (whether one or many), who pledged to tolerate any offense, and the speaker, who agreed to tell them the truth and risk the consequences.

If isegoria was fundamentally about equality, then, parrhesia was about liberty in the sense of license —not a right, but rather an unstable privilege enjoyed at the pleasure of the powerful. In Athenian democracy, that usually meant the majority of one’s fellow citizens, who were known to shout down or even drag speakers they disliked (including Plato’s brother, Glaucon) off the bema . This ancient version of “no-platforming” speakers who offended popular sensibilities could have deadly consequences—as the trial and death of Socrates, Plato’s friend and teacher, attests.

Noting the lack of success that Plato’s loved ones enjoyed with both isegoria and parrhesia during his lifetime may help explain why the father of Western philosophy didn’t set great store by either concept in his works. Plato no doubt would have noticed that, despite their differences, neither concept relied upon the most famous and distinctively Greek understanding of speech as logos —that is, reason or logical argument. Plato’s student, Aristotle, would identify logos as the capacity that made human beings essentially political animals in the first place. And yet neither isegoria nor parrhesia identified the reasoned speech and arguments of logos as uniquely deserving of equal liberty or license. Which seems to have been Plato’s point—how was it that a democratic city that prided itself on free speech, in all of its forms, put to death the one Athenian ruled by logos for speaking it?

Unsurprisingly perhaps, parrhesia survived the demise of Athenian democracy more easily than isegoria . As Greek democratic institutions were crushed by the Macedonian empire, then the Roman, parrhesia persisted as a rhetorical trope. A thousand years after the fall of Rome, Renaissance humanists would revive parrhesia as the distinctive virtue of the counselor speaking to a powerful prince in need of frank advice. While often couched in apologetics, this parrhesia retained its capacity to shock. The hard truths presented by Machiavelli and Hobbes to their would-be sovereigns would inspire generations of “libertine” thinkers to come.

Still, there was another adaptation of the parrhesiastic tradition of speaking truth to power available to early modern Europeans. The early Christians took a page from Diogenes’s book in spreading the “good news” of the Gospel throughout the Greco-Roman world—news that may not have sounded all that great to the Roman authorities. Many of the Christians who styled themselves as “Protestants” after the Reformation thought that a return to an authentically parrhesiastic and deliberately offensive form of evangelism was necessary to restore the Church to the purity of “primitive” Christianity. The early Quakers, for example, were known to interrupt Anglican services by shouting down the minister and to go naked in public “for a sign.”

Isegoria , too, had its early modern inheritors. But in the absence of democratic institutions like the Athenian ekklesia , it necessarily took a different form. The 1689 English Bill of Rights secured “the freedom of speech and debates in Parliament,” and so applied to members of Parliament only, and only when they were present in the chamber. For the many who lacked access to formal political participation, the idea of isegoria as an equal right of public speech belonging to all citizens would eventually migrate from the concrete public forum to the virtual public sphere.

For philosophers like Spinoza and Immanuel Kant, “free speech” meant primarily the intellectual freedom to participate in the public exchange of arguments. In 1784, five years before the French Revolution, Kant would insist that “the freedom to make public use of one’s reason” was the fundamental and equal right of any human being or citizen. Similarly, when Mill wrote On Liberty less than a century later, he did not defend the freedom of speech as such, but rather the individual “freedom of thought and discussion” in the collective pursuit of truth. While the equal liberty of isegoria remained essential for these thinkers, they shifted focus from actual speech —that is, the physical act of addressing others and participating in debate—to the mental exercise of reason and the exchange of ideas and arguments, very often in print. And so, over the course of two millennia, the Enlightenment finally united isegoria and logos in an idealized concept of free speech as freedom only for reasoned speech and rational deliberation that would have made Plato proud.

This logo-centric Enlightenment ideal remains central to the European understanding of free speech today. Efforts in Europe to criminalize hate speech owe an obvious debt to Kant, who described the freedom of (reasoned) speech in public as “the most harmless” of all. The same could never be said of ancient or early modern parrhesia , which was always threatening to speakers and listeners alike. Indeed, it was the obvious harm caused by their parrhesiastic evangelism to their neighbors’ religious sensibilities that led so many evangelical Protestants to flee prosecution (or persecution, as they saw it) in Europe for the greater liberty—or license—of the New World. American exceptionalism can thus be traced all the way back to the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries: while America got the evangelicals and libertines, Europe kept the philosophers.

Debates about free speech on American campuses today suggest that the rival concepts of isegoria and parrhesia are alive and well. When student protesters claim that they are silencing certain voices—via no-platforming, social pressure, or outright censorship—in the name of free speech itself, it may be tempting to dismiss them as insincere, or at best confused. As I witnessed at an event at Kenyon College in September, when confronted with such arguments the response from gray-bearded free-speech fundamentalists like myself is to continue to preach to the converted about the First Amendment, but with an undercurrent of solidaristic despair about “kids these days” and their failure to understand the fundamentals of liberal democracy.

No wonder the “kids” are unpersuaded. While trigger warnings, safe spaces, and no-platforming grab headlines, poll after poll suggests that a more subtle, shift in mores is afoot. To a generation convinced that hateful speech is itself a form of violence or “silencing,” pleading the First Amendment is to miss the point. Most of these students do not see themselves as standing against free speech at all. What they care about is the equal right to speech, and equal access to a public forum in which the historically marginalized and excluded can be heard and count equally with the privileged. This is a claim to isegoria , and once one recognizes it as such, much else becomes clear—including the contrasting appeal to parrhesia by their opponents, who sometimes seem determined to reduce “free speech” to a license to offend.

Recognizing the ancient ideas at work in these modern arguments puts those of us committed to America’s parrhesiastic tradition of speaking truth to power in a better position to defend it. It suggests that to defeat the modern proponents of isegoria— and remind the modern parrhesiastes what they are fighting for—one must go beyond the First Amendment to the other, orienting principle of American democracy behind it, namely equality . After all, the genius of the First Amendment lies in bringing isegoria and parrhesia together, by securing the equal right and liberty of citizens not simply to “exercise their reason” but to speak their minds. It does so because the alternative is to allow the powers-that-happen-to-be to grant that liberty as a license to some individuals while denying it to others.

In contexts where the Constitution does not apply, like a private university, this opposition to arbitrariness is a matter of culture, not law, but it is no less pressing and important for that. As the evangelicals, protesters, and provocateurs who founded America’s parrhesiastic tradition knew well: When the rights of all become the privilege of a few, neither liberty nor equality can last.

Translation of "speech" into Greek

λόγος, ομιλία, αγόρευση are the top translations of "speech" into Greek. Sample translated sentence: Speech is silver, silence is golden. ↔ Τα λίγα λόγια ζάχαρη και τα καθόλου μέλι.

(uncountable) The faculty of speech; the ability to speak or to use vocalizations to communicate. [..]

English-Greek dictionary

vocal communication [..]

Speech is silver, silence is golden.

Τα λίγα λόγια ζάχαρη και τα καθόλου μέλι.

Tom closed his speech with a beautiful song.

Ο Τομ έκλεισε την ομιλία του μ' ένα όμορφο τραγούδι.

an oration, session of speaking

The speech for the crown, however, is premature.

Η αγόρευση της πολιτικής αγωγής, ωστόσο, είναι πρώιμη.

Less frequent translations

Show algorithmically generated translations

Automatic translations of " speech " into Greek

Translations with alternative spelling

One of the music genres that appears under Genre classification in Windows Media Player library. Based on ID3 standard tagging format for MP3 audio files. Winamp genre ID # 101.

Images with "speech"

Phrases similar to "speech" with translations into greek.

- speech recognition Αναγνώριση ομιλίας · αναγνώριση ομιλίας

- farewell speech αποχαιρετιστήρια ομιλία

- Speech Transmission Quality Ποιότητα μετάδοσης ομιλίας

- hate speech Ρητορική μίσους · εκφράσεις μίσους · ρατσιστικά σχόλια · ρητορική μίσους

- Speech Interference Level Επίπεδο παρεμπόδισης συνομιλίας

- intelligibility of speech καταληπτότητα της ομιλίας

- reflected speech ανακλώμενη ομιλία

- Text-To-Speech Κείμενο σε ομιλία

Translations of "speech" into Greek in sentences, translation memory

Go Learn Greek

Learn all about Greek grammar, vocabulary and culture

Parts Of Speech

In Greek there are 10 parts of speech. Some of them we can conjugate:

Others we can’t:

Appendix : Greek punctuation

- 1.1 Άνω και κάτω τελεία ( : ) colon

- 1.2 Άνω τελεία (raised point)

- 1.3 Αποσιωπητικά (ellipsis)

- 1.4 Απόστροφος (apostrophe)

- 1.5 Εισαγωγικά (quotation marks)

- 1.6 Ενωτικό (hyphen)

- 1.7 Ερωτηματικό ( ; ) question mark

- 1.8 Θαυμαστικό (exclamation mark)

- 1.9 Κόμμα (comma)

- 1.10 Παρένθεση, παρενθέσεις (parentheses)

- 1.11 Παύλα (dash)

- 1.12 Τελεία (stop)

- 2.1 εισαγωγικά « » (guillemets)

- 2.2 παύλα — (em dash)

- 3 Greek keyboard

Punctuation marks [ edit ]

Άνω και κάτω τελεία ( : ) colon [ edit ].

- The colon is used in reporting direct speech, described in greater detail below : Ο Μπόξερ είπε : «Είναι νεκρός». ("Boxer said, "He is dead.")

- And to introduce a list: τα ψάρια : μουρούνα, γαύρος, ρέγγες, κολιός … ("the fish : cod, anchovy, herring, mackerel …")

Άνω τελεία (raised point) [ edit ]

· raised point ( Unicode (Greek) U+0387 ), equivalent to semi colon ;

- Separates groups of clauses in a sentence.

- Separates two parts of a sentence where a κόμμα is thought to be inadequate.

- To represent it in html use · — in Wiktionary and elsewhere U+0387 is automatically converted to the MIDDLE DOT (U+00B7).

Αποσιωπητικά (ellipsis) [ edit ]

… ellipsis ( Unicode (Basic Latin) U+2026 keyboard input Alt+0133 )

- Indicates an incomplete sentence or, in direct speech, unsaid words.

Απόστροφος (apostrophe) [ edit ]

' apostrophe ( Unicode (Basic Latin) U+0027 keyboard input Alt+0039 )

- It takes the place of a vowel which is omitted in pronunciation.

- and see ενωτικό ( enotikó )

Εισαγωγικά (quotation marks) [ edit ]

« » guillemets or quotation marks ( Unicode (Basic Latin) U+00AB / U+00BB keyboard input Alt+0171 / Alt+0187 )

- Used to punctuate direct speech ( qv ).

Ενωτικό (hyphen) [ edit ]

- hyphen ( Unicode (Basic Latin) U+002D )

- Used to mark the break in a word at the end of a line.

- and see απόστροφος ( apóstrofos )

Ερωτηματικό ( ; ) question mark [ edit ]

- Used at the end of interrogative sentences, in the same manner as the English question mark [ ? ]. «Γιατί, τότε», ρώτησε κάποιος, «τον είχε πολεμήσει με όλα τα μέσα ; » ("'Why then', someone asked, 'had he spoken so strongly against it ?' ")

Θαυμαστικό (exclamation mark) [ edit ]

! exclamation mark (keyboard input Alt+0033 )

- Used at the end of an exclamatory sentence and after interjections.

Κόμμα (comma) [ edit ]

, comma ( Unicode (Basic Latin) U+002C keyboard input Alt+0044 ) ( see also: υποδιαστολή )

- Used like the English comma to separate clauses, items in lists, etc. μουρούνα , γαύρος , ρέγγες , κολιός … ( cod, anchovy, herring, mackerel … )

- Used instead of the (English) decimal point in numbers. 2 , 95€ ( €2.95 )

- It is typographically identical to the υποδιαστολή , which is used to differentiate a few homophones: see: ό,τι and ότι

Παρένθεση, παρενθέσεις (parentheses) [ edit ]

( ) parenthesis

- Used to isolate an aside, comment or explanation from surrounding text.

Παύλα (dash) [ edit ]

— ― dash , horizontal bar ( Unicode (Basic Latin) U+2014 , U+2015 )

- Used in pairs to isolate text.

- Used to indicate a break in a sentence.

Τελεία (stop) [ edit ]

. full stop , period ( Unicode (Basic Latin) U+002E keyboard input Alt+0046 ) ( see also: άνω τελεία )

- Used like the English full stop or period to end sentences and indicate abbreviations. Τις Κυριακές δε δούλευε κανένας . ( On Sundays, no one worked. )

- Used instead of the (English) comma in large numbers. το κόστος του σπιτιού ήταν £260 . 950,00 ( the cost of the house was £260,950.00 )

Direct speech [ edit ]

There are two main conventions; the choice depends upon the writer or publisher.

εισαγωγικά « » ( guillemets ) [ edit ]

From "Animal Farm" by George Orwell ("η Φάρμα των ζώων" trans. Αγγελική Πετρή)

From "Ο ψεύτης παππούς" by Άλκη Ζέη

- Used especially when quoting direct speech in the middle of a paragraph.

- Occasionally phrases such as he asked Maria may be written inside the quotation marks.

- When speech continues into a new paragraph, as in English, the closing mark of the previous paragraph is omitted.

- The closing full stop is placed after the final quotation mark, but exclamation and question marks are placed before.

παύλα — ( em dash ) [ edit ]

Direct speech at the beginning of a paragraph may be introduced with a dash, and no speech marks:

Greek keyboard [ edit ]

- The keyboard for Standard Modern Greek.

- The diacritics are produced using the keys shown in red, followed by the appropriate vowel.

- The blue characters are produced on some keyboards by using the AltGr key.

- Greek appendices

Navigation menu

Editor's Pick

© Illustration: Philippos Avramides

Greek Salutations: A Glossary to Help You Sound Like a Local

The greek language is full of set phrases that act as greetings or blessings. here are 70 ways to wish someone well in greece, depending on the situation..

Paulina Björk Kapsalis | May 14th, 2021

The first time I went to a Greek wedding, a fellow non-native Greek speaker offered a friendly piece of advice: “You should try to learn all the greetings . You won’t get them right of course – but it’ll be funny.” She was right. In the receiving line, I mixed up the phrase meant for the couple and the one for the best man, then looked the father of the bride straight in the eye and mumbled “za za zoo” instead of “na sas zisoun” – an impossible phrase to pronounce without extensive practice, it means “may they live.”

Greeks are often bothered by the fact that there are no English translations for many common courteous phrases, such as “kali orexi,” for example. (This particular lack forces waiters at tourist destinations across Greece to resort to the French “bon appetit.”) In Greek, not only is there a way to wish someone a good appetite before a meal, but there is another phrase for wishing them good digestion once they’re finished eating – “kali honepsi.”

It seems the Greek language has a special greeting or wish for every occasion, and sometimes for no real occasion at all: there are several ways to encourage someone to enjoy a new purchase or a new haircut; there’s a greeting for the beginning of the week and the end of the work week; and there are several that are used to address the relatives of a person who’s actually celebrating something.

Greek small talk is so dependent on these phrases, in fact, that when it’s someone’s birthday , a whole conversation can be had using such wishes alone. When the government announced its measures for limiting the spread of Covid-19, a new way was quickly chosen for ending zoom calls and brief chance encounters on the street; “kali lefteria,” normally used to wish a woman good luck with a birth, is now also used to express a desire for the end of lockdown (“lefteria,” or “eleftheria,” means freedom).

Below is a list of greetings and benedictional phrases which, if you use them right, will make you sound like a local.

Hronia polla (χρόνια πολλά) : meaning “many years,” as in “and many more” or “many happy returns,” it is the most common Greek wish, used at most celebrations, including birthdays, name days and holidays.

Kai tou hronou (και του χρόνου) : meaning “and next year,” this is used in roughly the same way as hronia polla, for celebrations and good times. It can be followed by specific wishes for the coming year, such as “me igeia,” meaning “with health.”

Kali dunami (καλή δύναμη) : meaning “good strength,” this is said to someone about to tackle something difficult or tiring.

Kali epitihia (καλή επιτυχία) : this means “good luck” and is most commonly said to someone about to do something difficult, such as taking a test, or opening a business.

Kali tihi (καλή τύχη) : also meaning “good luck,” this version is more often used in situations where luck equals chance, such as the buying of a lottery ticket.

Kali evdomada (καλή εβδομάδα) : this means “good week” and is said on Mondays.

Kalo mina (καλό μήνα) : this means “good month” and is said on the 1st of every month.

Kalo Savvatokiriako (καλό Σαββατοκύριακο) : meaning “good weekend,” this is said on Fridays.

Me to kalo (με το καλό) : meaning “all being well,” this is used similarly to “God willing.”

Na ise kala (να είσαι καλά) : meaning “may you be well,” this versatile phrase can be added to a list of wishes at special occasions, but is most commonly used to thank someone, either for a favor or, often, for their wishes to you.

Na pas sto kalo (να πας στο καλό) : this means farewell, and is said on parting.

Christos anesti (Χριστός ανέστη) : meaning “Christ has risen,” this is said at the Anastasi celebration of the resurrection of Christ, on the eve of Holy Saturday.

Alithos o kirios (αληθώς ο Κύριος) : meaning “truly, the lord,” this is the response to “Christos anesti.”

Kales giortes (καλές γιορτές) : meaning “happy holidays,” this is used to wish someone a good religious holiday.

Kala hristougenna (καλά Χριστούγεννα) : this means “Merry Christmas.”

Kala koulouma (καλά κούλουμα) : meaning “a good Clean Monday,” this is said on the first day of Lent in the run-up to Easter.

Kali anastasi (καλή ανάσταση) : meaning “good resurrection,” this is said during Holy Week, in the run-up to the celebration of the resurrection of Christ.

Kali hronia (καλή χρονιά) : this means “Happy New Year.”

Kali protohronia (καλή πρωτοχρονιά) : this also means “Happy New Year.”

Kali sarakosti (καλή σαρακοστή) : meaning “good 40-day lent,” this is said at the beginning of Lent, in the run-up to Easter.

Kalo pasha (καλο πασχα) : this means “Happy Easter.”

Kai sta dika sou (και στα δικά σου) : this means “and to yours” and is said to unmarried guests at weddings, expressing the hope of getting together again soon at their wedding.

Kala stefana (καλά στέφανα) : meaning “good wreaths,” this refers to the wedding wreaths that are ceremoniously placed on the couples’ heads during the wedding and is used as “Have a wonderful wedding.”

Na sas zisoun (να σας ζήσουν) : this means “May they live” and is said to the parents of the bride and groom.

Na zisete (να ζήσετε) : this means “May you live” and said to the happy couple.

I ora i kali (η ώρα η καλή) : this means “The time is good,” and is said wish the couple a happy wedding.

Kalous apogonous (καλούς απογόνους) : this means “good offspring,” and is said to the couple as a fertility blessing.

Panta axia (Πάντα άξια) : meaning “always worthy,” this is said to the maid of honor.

Panta axios (Πάντα άξιος) : this also means “always worthy” and is said to the best man.

Vion Anthosparton (βίον ανθόσπαρτον) : this means “a life full of flowers.” It’s derived from Ancient Greek, and is said to the couple directly after the wedding.

Baptisms/new baby

Kali lefteria (καλή λευτεριά) : this meaning “good freedom” and is said to a pregnant woman, wishing her a good birth.

Me ena pono (με ένα πόνο) : meaning “with one pain,” this is another wish for an easy birth that can be expressed to pregnant women.

Na sas zisei (να σας ζήσει) : this means “May he/she live (a happy life)” and is said to the family of a newborn baby, either the first time you see the infant or at its baptism.

Panta axia (Πάντα άξια) : meaning “always worthy,” this is said to the godmother at a baptism.

Panta axios (Πάντα άξιος) : this also means “always worthy” and is said to the godfather at a baptism.

Hronia polla (χρόνια πολλά) : this means “many years”, as in “and many more.”

Na hairese… (να χαίρεσαι…) : this means “May you cherish…” To complete this wish, add whatever is good in the life of the person being celebrated, such as “tin ikogenia sou,” meaning “your family.”

Na ta ekatostiseis (να τα εκατοστίσεις) : this means “May you live to be a hundred years old.”

Na ton/tin hairese (να τον/την χαίρεσαι) : meaning “Cherish him/her,” this is said to the relatives of the birthday celebrant.

Oti epithimeis (ότι επιθυμείς) : this means “May your wishes come true.”

Polihronos/polihroni (πολύχρονος/πολύχρονη) : meaning “long-lived,” this is used to wish the birthday celebrant a long life.

Na hairese to onoma sou (να χαίρεσαι το όνομά σου) : this means “Cherish your name.”

Na ton/tin hairese (να τον/την χαίρεσαι) : this means “Cherish him/her,” and is said to the relatives of the person celebrating their name day.

( Learn more about Greek name days and how they are celebrated, and find out when yours is, here .)

Zoi se mas (ζωή σε μας) : meaning “life to us,” this respectful way to express the idea that life goes on is used between members of a grieving family.

Zoi se sas (ζωή σε σας) : meaning “life to you,” this is said to the bereaved by those outside the family.

Silipitiria (συλλυπητήρια) : this means “condolences.”

Eonia i mnimi (αιωνία η μνήμη) : this means “eternal memory,” as in to say: “May he/she be remembered forever.”

Na zisete na ton/tin thimaste (να ζήσετε να τον/ την θυμάστε) : this means ”May you live to remember him/her.”

When you get something new

Kaloriziko (καλορίζικο) : from the words for “good” and “roots,” this is said to congratulate someone on a big purchase.

Kalotaxido (καλοτάξιδο) : this means “May it travel well,” and is used to congratulate someone on getting a new vehicle.

Me geia (με γεια) : meaning “with health,” this is used to congratulate someone on a purchase or a haircut.

During a meal

Geia sta heria sou (Γεια στα χέρια σου) : this means “health to your hands” and is used as a blessing for the hands of the person who cooked your meal.

Kali honepsi (καλή χώνεψη) : meaning “good digestion,” this is said at the end of a meal.

Kali orexi (καλή όρεξη) : this means “good appetite” and is said before a meal.

Stin igia mas / Yiamas (στην υγειά μας / γειά μας) : this means “to our health,” and is used when raising glasses in a toast.

Stin igia sou / Yiasou (στην υγειά σου / γειά σου) : meaning “to your health,” this is used to single someone out when toasting.

Yiasou (γεια σου) : this means “your health” and is used as “Bless you” when someone sneezes.

Geitses (γείτσες) : this shares the same root as “yiasou” (“γεια,” meaning health) and is also said when someone sneezes.

Kali anarosi (καλή ανάρρωση) : this means “good recovery.”

Kala apotelesmata (καλά αποτελέσματα) : meaning “good results,” this is used to wish someone good medical test results.

Perastika (περαστικά) : this means “passing” and is used as “Get well soon.”

Siderenios (σιδερένιος) : from the word “sidero,” meaning iron, this is used to wish someone strength when they are battling an illness.

Travel & fun

Kali diaskedasi (καλή διασκέδαση) : this means “Have fun.”

Kales diakopes (καλές διακοπές) : this means “Have a good vacation.”

Kali antamosi (καλή αντάμωση) : this means “so long” or “until we meet again.”

Kalo taxidi (καλό ταξίδι) : this means “Have a good trip.”

Kala na perasis (καλά να περάσεις) : this means ”Have a good time.”

Work, school & military service

Kala apotelesmata (καλά αποτελέσματα) : meaning “good results,” this is used to wish someone good test results on an exam.

Kales doulies (καλές δουλειές) : this means “good business” and is used when someone opens a new business, and at the beginning of a busy season.

Kali arhi (καλή αρχή) : meaning “good start,” this is said to someone starting a new job, or a new school.

Kali proodo (καλή πρόοδο) : this means “good progress” and is said to congratulate a school graduate.

Kali stadiodromia (καλή σταδιοδρομία) : this means “good career” and is used to congratulate a university graduate, or someone moving up in their career.

Kali thiteia (καλή θητεία) : this means “good service” and is said to someone beginning their military service.

Kalos fantaros (καλός φαντάρος) : meaning “good soldier,” this is another way of wishing someone well as they begin their military service.

Kalos politis (καλός πολίτης) : this means “good citizen” and is said to those completing their military service, as well as to prisoners completing their jail time.

Did we forget something? Send us any suggestions for this list on Instagram, @greece_is.

SUBSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTER

Thank you for signing up.

Aegean Islands

Easter on hydra: ceremonies by the sea.

Renowned for its maritime heritage and the important role it...

Eat Well: 3 Healthy, Delicious (and Vegan-Friendly) Greek Recipes

These 3 simple dishes, drawing on time-tested Greek recipes, use...

An Expert’s Greek Food Experience

Celebrity chef and writer Diane Kochilas introduces us to a...

8 Things To Do With Your Kids in Athens This Christmas

From light shows and Santa Claus appearances to hot chocolate...

Share This Page

Greece Is Blog Posts

An ode to local products.

BY Yiouli Eptakili

No more avocado toast and croque-madames. From Thessaloniki to Crete...

read more >

How Can Greece Become a Gastro-Tourism Destination?

It’s about more than just taking a trip...

Leaving Room in Greece for Everyone

BY Greece Is

Labor Day, this year September 5, marks the...

Most Popular

Peloponnese

a journey back in time: the newly restored bourtzi castle in nafplio

walk like an athenian: the 34th athens fashion week

cine paris: the iconic open-air cinema of plaka is back

agistri, an idyllic sunday getaway

5+1 reasons for a spring day trip to aegina

empowering mykonos: women’s roles in shaping history

More Information

- Distribution

Publications

- Athens Summer 2015 Edition

- Santorini 2015 Edition

- Democracy Edition

- Peloponnese 2015 Edition

Sign Up for Premium Content, Special Offers & More.

- Terms of use

- Privacy Policy

Social Media

.© 2024 GREECE IS, NEES KATHIMERINES EKDOSEIS SINGLE-MEMBER S.A.

Powered by: Relevance | Developed by: Stonewave

Free Greek Text to Speech & AI Voice Generator

How to create greek text to speech, find a voice, select the model, enter text & adjust settings, generate audio.

Rich Greek Linguistic Detail

Contextual awareness, natural pauses, extensive voice range, customizable accents, tone and emotional control, greek ai voice applications, storytelling and audiobooks, marketing and branding, educational content, voice assistants and ivr, hear from our text to speech users.

The voices are really amazing and very natural sounding. Even the voices for other languages are impressive. This allows us to do things with our educational content that would not have been possible in the past.

It's amazing to see that text to speech became that good. Write your text, select a voice and receive stunning and near-perfect results! Regenerating results will also give you different results (depending on the settings). The service supports 30+ languages, including Dutch (which is very rare). ElevenLabs has proved that it isn't impossible to have near-perfect text-to-speech 'Dutch'...

We use the tool daily for our content creation. Cloning our voices was incredibly simple. It's an easy-to-navigate platform that delivers exceptionally high quality. Voice cloning is just a matter of uploading an audio file, and you're ready to use the voice. We also build apps where we utilize the API from ElevenLabs; the API is very simple for developers to use. So, if you need a...