Module 12: Personality Disorders

Case studies: personality disorders, learning objectives.

- Identify personality disorders in case studies

Case Study: Latasha

Latasha was a 20-year-old college student who lived in the dorms on campus. Classmates described Latasha as absent-minded and geeky because she didn’t interact with others and rarely, if ever, engaged with classmates or professors in class. She usually raced back to her dorm as soon as classes were over. Latasha primarily stayed in her room, did not appear to have any friends, and had no interest in the events happening on campus. Latasha even asked for special permission to stay on campus when most students went home for Thanksgiving break.

Now let’s examine some fictional case studies.

Case Study: The Mad Hatter

The Mad Hatter, from Alice in Wonderland , appears to be living in a forest that is part of Alice’s dream. He appears to be in his mid-thirties, is Caucasian, and dresses vibrantly. The Mad Hatter climbs on a table, walks across it, and breaks plates and teacups along the way. He is rather protective of Alice; when the guards of the Queen of Hearts come, he hides Alice in a tea kettle. Upon making sure that Alice is safe, Mad Hatter puts her on his hat, after he had shrunk her, and takes her for a walk. While walking, he starts to talk about the Jabberwocky and becomes enraged when Alice tells him that she will not slay the Jabberwocky. Talking to Alice about why she needs to slay the Jabberwocky, the Mad Hatter becomes emotional and tells Alice that she has changed.

The Mad Hatter continues to go to lengths to protect Alice; he throws his hat with her on it across the field, so the Queen of Heart’s guards do not capture her. He lies to the Queen and indicates he has not seen Alice, although she is clearly sitting next to the Queen. He decides to charm the Queen, by telling her that he wants to make her a hat for her rather large head. Once the White Queen regained her land again, the Mad Hatter is happy.

Case Study: The Grinch

The Grinch, who is a bitter and cave-dwelling creature, lives on the snowy Mount Crumpits, a high mountain north of Whoville. His age is undisclosed, but he looks to be in his 40s and does not have a job. He normally spends a lot of his time alone in his cave. He is often depressed and spends his time avoiding and hating the people of Whoville and their celebration of Christmas. He disregards the feelings of the people, knowingly steals and destroys their property, and finds pleasure in doing so. We do not know his family history, as he was abandoned as a child, but he was taken in by two ladies who raised him with a love for Christmas. He is green and fuzzy, so he stands out among the Whos, and he was often ridiculed for his looks in school. He does not maintain any social relationships with his friends and family. The only social companion the Grinch has is his dog, Max. The Grinch had no goal in his life except to stop Christmas from happening. There is no history of drug or alcohol use.

- Modification, adaptation, and original content. Authored by : Julie Manley for Lumen Learning. Provided by : Lumen Learning. License : CC BY: Attribution

- Case Studies: The Grinch. Authored by : Dr. Caleb Lack and students at the University of Central Oklahoma and Arkansas Tech University. Located at : https://courses.lumenlearning.com/abnormalpsychology/chapter/antisocial-personality-disorder/ . License : CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- The Mad Hatter. Authored by : Loren Javier. Located at : https://www.flickr.com/photos/lorenjavier/4031000212/ . License : CC BY-ND: Attribution-NoDerivatives

- The Grinch. Located at : https://pixy.org/1066311/ . License : CC0: No Rights Reserved

Personality Development: Michelle Obama Case Study

The term “personality” refers to a sum of character traits in a person. Therefore, personality development implies that the personality traits evolve from the childhood basis to the full development of individual differences in a character of a grown-up. This case study investigates the personality development illustrated by an example of Michelle Obama, First Lady of the United States of America. She was chosen due to her prominent personality features, outstanding life experience and the fact that she is a worthy role model for modern society; consequently, such development can be an interesting example to consider.

Michelle LaVaughn Obama, née Robinson, was born on January 17, 1964, in Calumet Park Illinois, to a family of a water plant worker and a housewife. She is now able to trace the history of her family back to a Friendfield Plantation in Georgetown, S.C. where her great-great-grandfather worked as a slave, while later his descendants moved North and settled in Illinois. However Mrs. Obama has learned of her ancestry only during a presidential campaign of her husband, and this knowledge has had a great impact on her (Murray, 2008, p. 1).

She graduated from school in1981 as a salutatory student and later studied sociology at Princeton University, from which she graduated BoA cum laude. In 1988, she also graduated from Harvard University as Juris Doctor and began her law practice in Harvard Legal Aid Bureau. Later she also worked in various non-profit organizations but reduced her job responsibilities to help her husband, Barak Obama, whom she married in 1992, with his presidential campaign. The couple raises two daughters, and Michelle considers her family the main life priority. Mrs. Obama is regarded as a fashion icon and a trend-setter ( Michelle Obama Biography , n.d., par. 1-21).

For further exploration of Michelle Obama’s personality development, it is important to mention the models, according to which an individual’s personality development can be explained. These models include psychoanalytic and neo-analytic theories, psychosocial theories, trait, evolutionary, genetic/biological approaches, cognitive, behavioral, and social learning theories, and humanistic theories. For the beginning of the analysis, it would be appropriate to use the psychoanalytic / neo-analytic model, as it is one of the most basic and rather comprehensive theories, which can be considered as both advantage and disadvantage because it does not leave much possibility for other explanations.

According to those theories, based on teachings of Sigmund Freud, the parts of psyche, called “id”, “ego” and “superego” are balanced within each individual, but while Freud himself thought ego to be a weak structure, his successors, the neo-analytics, claimed that ego, containing the functions of learning, memory, and cognitive skills is a part that is the strongest from birth. A development, in this case, takes place in solving the so-called “basic conflicts”, which may serve to temper the character, or result in personality problems if such conflicts were not solved.

For Michelle Obama, an example of such conflict would have been an illness that her father suffered, the multiple sclerosis, which, however, did not stop him from pursuing his goals in life and teaching his daughter the same values ( Fraser Robinson III ~ Michelle Obama’s Father , par. 1-16). This probably was also the reason Michelle is often a participant of charity and non-profit organizations – because of her need to help people and treat them with kindness.

The psychosocial theory was first introduced by psychologist Erik Erikson; it suggests that eight stages of development during one’s life, at which the person learns to accept different virtues, such as hope, will, purpose, competence, fidelity, love, care and wisdom. If one of the stages is missing, the value of its virtue may be lost. This theory encompasses the whole life’s development, but the order of the stages is often argued, and it is not always possible to trace the trajectory of a person’s life. According to this theory, Michelle Obama has successfully passed the stages of life involving purpose, competence (her studies), love and fidelity (her family) and at her adulthood she may be learning again how to care and make her life count, in which she definitely succeeds, both in terms of social and family life.

The trait theory, together with evolutionary and biological theories, presumes that a few fundamental units define the individual’s behavior and that these traits are defined by genetics (McLeod, 2014, par. 22-30). Therefore, further development is defined by these innate factors. These theories place emphasis on conducting psychometric tests (McLeod, par. 24), which can give a high level of precision in defining a character, some critics mention, that “traits are often poor predictors of behavior. While an individual may score high on assessments of a specific trait, he or she may not always behave that way in every situation … trait theories do not address how or why individual differences in personality develop or emerge” (Cherry, 2015, par. 16).

For using this theory, it may be important to investigate the family of Michelle Obama, to understand better, what kind of person she is, and how her legacy could influence her personality development. As it may be seen from her family tree, her ancestors were mostly hard-working people, who were proud of what they did and upheld traditional values; they believed that it was important to educate their children and give them a better life, which was one of the reasons the family moved to the north (Murray, 2008, p.2-4). It is clear that Michelle Obama inherited their dutifulness, perfectionism, independence, but also warmth and liveliness. This is how she became who she is now – a First Lady, a renowned philanthropist, and a trend-setter.

The humanistic or existential approach claims another important focus for a psychologist:

Factors that are specifically human, such as choice, responsibility, freedom, and how humans create meaning in their lives. Human behavior is not seen as determined in some mechanistic way, either by inner psychological forces, schedules of external reinforcement, or genetic endowments, but rather as a result of what we choose and how we create meaning from among those choices. (Beneckson, n.d., par. 42)

It means that understanding oneself and thriving to improve one’s personality may lead to healthy development or the so-called “self-actualization.” Existentialists may also add:

It requires active intention to create authenticity … Man is thrown into the world against his will, and must learn how to coexist with nature, and the awareness of his own death … To be healthy, humans must choose a course of action that leads to … the productive orientation. This is defined as working, loving, and reasoning so that work is a creative self-expression and not merely an end in itself. (Beneckson, n.d., par. 47)

This approach allows to take a different look at human’s psyche, disregarding the doctrines of Freudian, biological and behaviorist theories, however, it is often criticized for being too anthropocentric and idealistic.

For Mrs. Obama, the personal development in terms of humanistic theory may be illustrated with her life experiences, such as life within her family and a brother, which taught her how to listen to other people and get along with them. Later she also developed her working skills after she graduated, and her self-actualization lied in the field of law practice until she made a decision to help her husband. Michelle claimed that her family was her highest priority, and her choice was to work along with her husband and give her love to him and their children, all the while being able to satisfy her own need in self-actualization. The balance between these factors allows a person to find a psychological calm and harmony.

To conclude this research, it would be fair to assume, that although various approaches can be used to better understand an individual’s personality development, all of them can be useful for different scenarios. For example, it may be difficult to use the genetic method, when little or nothing is known about a person’s origins and his or her family. An existential approach should also be used with caution, as this is the least conservative and the newest method in psychology, which means some of its ideas may not have enough proof.

Nevertheless, every method has the right of existence however for a comprehensive and thorough understanding a deep and complex structure, that is the human personality, it may be advisable to unite some of the approaches. It would allow to gather more information, and the cross comparison of the results may highlight the features that previously were not noticed. It is highly important for a psychologist to follow the good practice but also to be versatile and flexible with the use of various tools to achieve better results in assessment and research.

Reference List

Beneckson, R. E. (n.d.) Personality Theory. A Brief Survey of the Field Today and Some Possible Future Directions . Web.

Cherry, K. (2015), Trait Theory of Personality. The Trait Approach to Personality . Web.

Fraser Robinson III ~ Michelle Obama’s Father. (n.d.). Web.

McLeod, S. (2014). Theories of personality . Web.

Michelle Obama Biography . (n.d.). Web.

Murray, S. (2008). A Family Tree Rooted In American Soil. The Washington Post. Web.

- Michelle Obama American Dream Speech Analysis –

- Book Report on Michelle Obama's Memoir "Becoming"

- Story of a Woman: "Becoming" by Michelle Obama

- Intelligence Theories Critique

- Personality Psychology: Cinderella's Personality

- Study of Values: 'A Scale for Measuring the Dominant Interests in Personality' by G. Allpor

- Heroism Concept and Its Causes

- Criminality and Personality Theory

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2022, January 29). Personality Development: Michelle Obama. https://ivypanda.com/essays/personality-development-case-study-michelle-obama/

"Personality Development: Michelle Obama." IvyPanda , 29 Jan. 2022, ivypanda.com/essays/personality-development-case-study-michelle-obama/.

IvyPanda . (2022) 'Personality Development: Michelle Obama'. 29 January.

IvyPanda . 2022. "Personality Development: Michelle Obama." January 29, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/personality-development-case-study-michelle-obama/.

1. IvyPanda . "Personality Development: Michelle Obama." January 29, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/personality-development-case-study-michelle-obama/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Personality Development: Michelle Obama." January 29, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/personality-development-case-study-michelle-obama/.

- Testimonial

- Web Stories

Learning Home

Not Now! Will rate later

MBA Case Studies - Solved Examples

Need of MBA Case Studies

Case i: chemco case.

- ChemCo is a quality leader in the U.K. car batteries market.

- Customer battery purchases in the automobile market are highly seasonal.

- The fork-lift business was added to utilize idle capacity during periods of inactivity.

- This is a low-growth industry (1% annual growth over the last two years)

- Large customers are sophisticated and buy based on price and quality. Smaller customers buy solely on price.

- There is a Spanish competitor in the market who offers low priced batteries of inferior quality.

Essential MBA GD Guide: Key Topics with Strategies Free

- Importance of Group Discussions

- Tips and Strategies to handle a GD

- Top 25 GD topics

- Free Download

- Established player in car batteries

- Losing heavily in fork-lift truck batteries

- Old fashioned owner resistance to change

- Low priced competitors

- Foreign competitors gaining market share

- Decisive Interview, GD & Essay prep

- GD: Topics 2021

- GD: Approach

- GD: Do's and Don'ts

- GD: Communications

- Solved GDs Topics

GD Introduction

- Types of GD topics: Techniques

- GD: Ettiquette

- GD: Content

- Solved Case Studies

- High quality product, but low end customers care more about price than quality

- Mismanaged product diversification in a price sensitive market

- Alternative 1: Establish an Off-Brand for the fork-lift business

- Alternative 2: Educate the customer market about product quality

- Alternative 3: Exit the fork-lift battery business

- Establishing the firm's quality image

- Increase in market share

- Increase in sales

- Cost of the product

- Protect firm's quality image in the automobile industry

- Redesigned product to reduce the cost of manufacture

- Low price to enable it to compete with Spanish producer

- Make use of the quality leadership in car batteries market

- Offer reliability testing, extended warranties etc. to promote quality image

- Set higher prices to extract surplus from these advantages

- A passive strategy, not proactive

- Recommendations: Alternative 1 is recommended in this case. Since the firm operates in an industry which has low growth, hence it can expand market share and sales only by taking the customers from other players. Hence, it needs to tackle the Spanish competitor head-on by aggressively pricing its product. At the same time, launching a low-priced product under the same brand name erodes the high quality image in the car batteries market. Hence, the best option is to go for an off-brand to target the fork-lift customers who are increasingly becoming price sensitive. This will enable the company to ward off the threat in short-term and build its position strongly in the long-term.

Case II: NAKAMURA LACQUER COMPANY

- The Nakamura Lacquer Company: The Nakamura Lacquer Company based in Kyoto, Japan was one of the many small handicraft shops making lacquerware for the daily table use of the Japanese people.

- Mr. Nakamura- the personality: In 1948, a young Mr. Nakamura took over his family business. He saw an opportunity to cater to a new market of America, i.e. GI's of the Occupation Army who had begun to buy lacquer ware as souvenirs. However, he realized that the traditional handicraft methods were inadequate. He was an innovator and introduced simple methods of processing and inspection using machines. Four years later, when the Occupation Army left in 1952, Nakamura employed several thousand men, and produced 500,000 pieces of lacquers tableware each year for the Japanese mass consumer market. The profit from operations was $250,000.

- The Brand: Nakamura named his brand “Chrysanthemum” after the national flower of Japan, which showed his patriotic fervor. The brand became Japan's best known and best selling brand, being synonymous with good quality, middle class and dependability.

- The Market: The market for lacquerware in Japan seems to have matured, with the production steady at 500,000 pieces a year. Nakamura did practically no business outside of Japan. However, early in 1960, when the American interest in Japanese products began to grow, Nakamura received two offers

- The Rose and Crown offer: The first offer was from Mr. Phil Rose, V.P Marketing at the National China Company. They were the largest manufacturer of good quality dinnerware in the U.S., with their “Rose and Crown” brand accounting for almost 30% of total sales. They were willing to give a firm order for three eyes for annual purchases of 400,000 sets of lacquer dinnerware, delivered in Japan and at 5% more than what the Japanese jobbers paid. However, Nakamura would have to forego the Chrysanthemum trademark to “Rose and Crown” and also undertaken to sell lacquer ware to anyone else the U.S. The offer promised returns of $720,000 over three years (with net returns of $83,000), but with little potential for the U.S. market on the Chrysanthemum brand beyond that period.

- The Semmelback offer: The second offer was from Mr. Walter Sammelback of Sammelback, Sammelback and Whittacker, Chicago, the largest supplier of hotel and restaurant supplies in the U.S. They perceived a U.S. market of 600,000 sets a year, expecting it to go up to 2 million in around 5 years. Since the Japanese government did not allow overseas investment, Sammelback was willing to budget $1.5 million. Although the offer implied negative returns of $467,000 over the first five years, the offer had the potential to give a $1 million profit if sales picked up as anticipated.

- Meeting the order: To meet the numbers requirement of the orders, Nakamura would either have to expand capacity or cut down on the domestic market. If he chose to expand capacity, the danger was of idle capacity in case the U.S. market did not respond. If he cut down on the domestic market, the danger was of losing out on a well-established market. Nakamura could also source part of the supply from other vendors. However, this option would not find favor with either of the American buyers since they had approached only Nakamura, realizing that he was the best person to meet the order.

- Decision problem: Whether to accept any of the two offers and if yes, which one of the two and under what terms of conditions?

- To expand into the U.S. market.

- To maintain and build upon their reputation of the “Chrysanthemum” brand

- To increase profit volumes by tapping the U.S. market and as a result, increasing scale of operations.

- To increase its share in the U.S. lacquerware market.

- Profit Maximization criterion: The most important criterion in the long run is profit maximization.

- Risk criterion: Since the demand in the U.S. market is not as much as in Japan.

- Brand identity criterion: Nakamura has painstakingly built up a brand name in Japan. It is desirable for him to compete in the U.S. market under the same brand name

- Flexibility criterion: The chosen option should offer Nakamura flexibility in maneuvering the terms and conditions to his advantage. Additionally, Nakamura should have bargaining power at the time of renewal of the contract.

- Short term returns: Nakamura should receive some returns on the investment he makes on the new offers. However, this criterion may be compromised in favor of profit maximization in the long run.?

- Reject both: React both the offers and concentrate on the domestic market

- Accept RC offer: Accept the Rose and Crown offer and supply the offer by cutting down on supplies to the domestic market or through capacity expansion or both

- Accept SSW: offer; accept the SSW offer and meet it through cutting down on supply to the domestic market or through capacity expansion or both. Negotiate term of supply.

- Reject both: This option would not meet the primary criterion of profit maximization. Further, the objective of growth would also not be met. Hence, this option is rejected.

- Accept RC offer: The RC offer would assure net returns of $283,000 over the next three yeas. It also assures regular returns of $240,000 per year. However, Nakamura would have no presence in the U.S. with its Chrysanthemum brand name The RC offer would entail capacity expansion, as it would not be possible to siphon of 275,000 pieces from the domestic market over three years without adversely affecting operations there. At the end of three years, Nakamura would have little bargaining power with RC as it would have an excess capacity of 275,000 pieces and excess labor which it would want to utilize. In this sense the offer is risky. Further, the offer is not flexible. Long-term profit maximization is uncertain in this case a condition that can be controlled in the SSW offer. Hence, this offer is rejected.

- Accept SSW offer: The SSW offer does not assure a firm order or any returns for the period of contract. Although, in its present form the offer is risky if the market in the U.S. does not pick up as expected, the offer is flexible. If Nakamura were to exhibit caution initially by supplying only 300,000 instead of the anticipated 600,000 pieces, it could siphon off the 175,000 required from the domestic market. If demand exists in the U.S., the capacity can be expanded. With this offer, risk is minimized. Further, it would be competing on its own brand name. Distribution would be taken care of and long-term profit maximization criterion would be satisfied as this option has the potential of $1 million in profits per year. At the time of renewal of the contract, Nakamura would have immense bargaining power.

- Negotiate terms of offer with SSW: The terms would be that NLC would supply 300,000 pieces in the first year. If market demand exists, NLC should expand capacity to provide the expected demand.

- Action Plan: In the first phase, NLC would supply SSW with 300,000 pieces. 125,000 of these would be obtained by utilizing excess capacity, while the remaining would be obtained from the domestic market. If the expected demand for lacquer ware exists in the U.S., NLC would expand capacity to meet the expected demand. The debt incurred would be paid off by the fifth year.

- Contingency Plan: In case the demand is not as expected in the first year, NLC should not service the U.S. market and instead concentrate on increasing penetration in the domestic market.

FAQs about MBA Case Studies

- Group Discussions

- Personality

- Past Experiences

Most Popular Articles - PS

100 Group Discussion (GD) Topics for MBA 2024

Solved GDs Topic

Top 50 Other (Science, Economy, Environment) topics for GD

5 tips for starting a GD

GD FAQs: Communication

GD FAQs: Content

Stages of GD preparation

Group Discussion Etiquettes

Case Study: Tips and Strategy

Practice Case Studies: Long

Practice Case Studies: Short

5 tips for handling Abstract GD topics

5 tips for handling a fish market situation in GD

5 things to follow: if you don’t know much about the GD topic

Do’s and Don’ts in a Group Discussion

5 tips for handling Factual GD topics

How to prepare for Group Discussion

We use cookies to enhance our website for you. Proceed if you agree to this policy or learn more about it.

- Essay Database >

- Essays Samples >

- Essay Types >

- Case Study Example

Personality Case Studies Samples For Students

112 samples of this type

If you're seeking a viable method to streamline writing a Case Study about Personality, WowEssays.com paper writing service just might be able to help you out.

For starters, you should skim our extensive directory of free samples that cover most various Personality Case Study topics and showcase the best academic writing practices. Once you feel that you've figured out the major principles of content organization and taken away actionable ideas from these expertly written Case Study samples, composing your own academic work should go much smoother.

However, you might still find yourself in a situation when even using top-notch Personality Case Studies doesn't allow you get the job accomplished on time. In that case, you can contact our experts and ask them to craft a unique Personality paper according to your individual specifications. Buy college research paper or essay now!

Randle Mcmurphy In The One Flew Over The Cuckoo's Nest Case Study Samples

Clinical diagnosis and rationale for the diagnosis, case study on the case of kname:institution:course:tutor:date of submission, the case of k, case study on abnormal psychology: charles manson, introduction.

Don't waste your time searching for a sample.

Get your case study done by professional writers!

Just from $10/page

Schizophrenic Spectrum And Other Psychotic Disorders Case Study Samples

Good example of case study on order# 209969004, human resource management, case study on egoism, sample case study on organizational behaviors.

Organizational behavior is the of study that explores the collision that structures, groups and individuals, have on behavior within an organization for the intention of applying such information towards taming an organization's efficiency. It understands the employees’ role and them understanding the manager’s role in the accurate manner without misconception in favor of the organization. In this case study, a retail shop sells teddy bears and Clark the manager determines her personalities in her organization” (Giacobbe, 2009).

Maxine’s Clark’s personality

Example of occupation: singer case study, free case study on gps-to-go takes on garmin.

[Your first name - initial of middle name and last name with titles (like Mr. or Dr.)]

[Your institute/university’s name goes here]

Free personality types and self-evaluation case study example, types of different personalities.

Freud and Fromm studied four different types of personalities possessed by human beings. They are discussed in the following manner from a leadership perspective:

The Erotic Personality

Individuals that possess this personality want to be loved and needed by others all the time. Compared to respect, people in this personality group tend to emphasize more on being liked and loved by others. They want to be known to others and wish to actively socialize with others. In all erotic personality holders are attention seekers and depend on others to make them happy.

The Obsessive Personality

Antisocial personality disorder case study case study, antisocial personality disorder: case study.

Antisocial Personality Disorder (ASPD) is a type of condition that corrupts an individual mind, emotions, thoughts and behavior. The affected person develops behaviors destructive and harmful to others and generally poses as a danger to society. The individuals tend to have long histories of violating peoples’ rights; they are always aggressive, show no remorse and usually do not know the distinction between truths and lie (Barlow and Durand, 2009).

Good Example Of Case Study On Kinaxis Chooses Sales Reps With Personality

What selection methods did bo dolan use for hiring salespeople, factors contributing to juvenile delinquent behaviour: exemplar case study to follow, case study on alan mulally, ceo, ford motor company.

In seeking success, Ford Motor Company entrusts the services of Alan Mulally, as the CEO. Having worked for Boeing, Mulally appears ready for this task as he embarks on undertaking a thorough research at Ford immediately he arrives, in order to study and formulate the best strategy for the company. As Ford Company is geared towards success, Mulally’s style of leadership is analyzed, as well as his personality dimension elements. The methods Mulally introduces at Ford are evaluated for effectiveness, while seeking for evidence of evidence based management at Ford. Furthermore, Mulally’s elements of communication openness are analyzed.

Case Study On Interview Profile

Interview profile, free adulthood case study case study example, introduction, janet's schizophrenic episode case study.

1. What is the precipitating stressor event that probably triggered the onset of Janet's Schizophrenic episode? What other factors may have contributed?

The Reign Of Napoleon Bonaparte Case Study Sample

Borderline personality disorder case study, borderline personality disorder: case study.

Karen’s Case

Karen was admitted in the intensive care unit of West Raymond medical Center after she knowingly took an overdose of sedatives in addition to alcohol in a suicide attempt following a disagreement with her man.

Domestic Violence Case Study Example

Personality case study, case study on personality disorders identification assignment, personality disorders: paranoid, schizoid, schizotypal, histrionic, narcissistic, borderline, antisocial, dependent and obsessive-compulsive.

Donna Donna has histrionic personality disorder. She used dramatic tactics to gain the attention of everyone at the party, such as boasting about being an actress and pretending to faint.

William has schizotypal personality disorder. He expressed beliefs and behaviors that were seen as odd and strange by everyone else, such as talking about negative forces and psychic soul-spot.

Sherry has borderline personality disorder. She suffered from emotional instability, dramatic changes in mood, and impulsive behavior. She also demonstrated para-suicidal behavior as she took aspirin in a weak attempt to harm herself, which is characteristic of this disorder.

Case Study On The Reign Of Napoleon Bonaparte

Free thomas' five general approaches to managing conflict include the following case study sample, management leadership, dora's case study example, marriage and family system case studies examples, good example of the beauty of sorbet case study case study, theoretical framework case studies examples, bss company startup analysis case studies examples, the beauty of sorbet case study case study to use for practical writing help, counselling theory case study, counselling theory, next leader for asia pacific: case study you might want to emulate, good case study about mba 5325, free mental health case study example, methodology case studies example, video game violence and its effects on children, good case study on alzheimers disease, mgmt331: week #8 paper: case study examples, free case study on personality and psychological disorders, personality and psychological disorders, bipolar personality disorders case study examples, the case of angelina jolie, borderline personality disorder case study sample, case study on david parker ray, changing mindset case study analysis: free sample case study to follow, strong hate for public speaking- notably, richard branson does not like standing in front of an audience giving speeches. (anton) case study template for faster writing, free relationship of the conflict experience and the course text case study example, personal case study.

Communication Personal Case Study

Interpersonal Conflict

Exemplar case study on conflict resolution to write after, example of clinical application of theory case study, good case study on motivation in learning and leadership, hr case evaluation #1 case study sample, free personality and development theories case study sample, good example of early onset of alzheimer’s, on alice case study, good example of stress management case study, principles of effective time management violated by chet.

Chet is not managing his time effectively because he is violating two key principles of effective time management: (1) spending some of his time on important tasks and (2) failure to comfortably say NO (Whetten and Cameron 121). From the case study, Chet is violating the first principle because he is spending all his time on urgent tasks. He also violating principle two because he is seen trying to solve everything that is presented to him.

Rules of Efficient Time Management for Managers Violated by Chet

Case study on hotel rwanda, good case study about key individuals, good essentials of psychology case study example, example of case study on green river murders, example of case study on connections to developmental theories, case study on john bio psychosocial profile 4, psychology: case study.

Introduction 3

Initial interview 4 Assessment formulation methods utilized 4 Assessment of John presenting problems and goals 5 Analysis and critique of MMT approach 6 Agreed goals 6 Treatment plan 6 CBT interventions 7 Intervention for cognitions-thoughts records 7 Benefits of the approach 7 Interventions for behavior- activity scheduling/diversion techniques 8 Benefits of the approach/ interaction 8 Interventions for imagery/interpersonal- imagery based exposure 8 Benefit of approach 9 Intervention for sensation- relaxation/ visualization 10 Conclusion 11

APPENDIX 1 13

5-axis diagnosis case study.

Lucy suffers of a major depression or depressive condition. She is getting the attention or medication with the antidepressants. This depressive episode is causing a lot of disturbance in her daily life activities. The medical pain is extreme hence making her to fail going to her workplace.

She is suffering from a personality disorder, which has contributed to the development of the depression. The attempted to commit suicide shaped her condition of depression. Her history of depression is as a result of the medical pain and being diagnosed with fibromyalgia. The personality disorder induces the depressive episode in axis I.

Case Study on Knowledge Management in Marketing

Example of case study on star bucks.

Password recovery email has been sent to [email protected]

Use your new password to log in

You are not register!

By clicking Register, you agree to our Terms of Service and that you have read our Privacy Policy .

Now you can download documents directly to your device!

Check your email! An email with your password has already been sent to you! Now you can download documents directly to your device.

or Use the QR code to Save this Paper to Your Phone

The sample is NOT original!

Short on a deadline?

Don't waste time. Get help with 11% off using code - GETWOWED

No, thanks! I'm fine with missing my deadline

Snapsolve any problem by taking a picture. Try it in the Numerade app?

Learn More Psychology

- Freudian Psychology

Case Studies of Sigmund Freud

Introduction to sigmund freud's case histories, including little hans, anna o and wolf man..

Permalink Print |

Accounts of Freud ’s treatment of individual clients were key to his work, including the development of psychodynamic theory and stages of psychosexual development . Whilst the psychoanalyst’s use of case studies to support his ideas makes it difficult for us to prove or disprove Freud’s theories, they do provide fascinating insights into his day-to-day consultations with clients and offer clues as to the origins of his influential insights into how the human mind functions:

Little Hans

Perhaps the best known case study published by Freud was of Little Hans. Little Hans was the son of a friend and follower of Freud, music critic Max Graf. Graf’s son, Herbert, witnessed a tragic accident in which a horse carrying a heavily loaded cart collapsed in the street. Five year old Little Hans developed a fear of horses which led him to resist leaving the house for fear of seeing the animals. His father detailed his behavior in a series of letters to Freud and it was through these letters that the psychoanalyst directed the boy’s treatment. Indeed, the therapist and patient only met for a session on one occasion, but Freud published his case as a paper, Analysis of a Phobia in a Five-Year-Old Boy (1909), in support of his theory of the Oedipus complex and his proposed stages of psychosexual development.

Freud Cases

- Rat Man: A Case of 'Obsessional Neurosis'

- Dora Case Study

- Inside the Mind of Daniel Schreber

- The Case of Little Hans

Little Hans’ father relayed to Freud his development and noted that he had begun to show an intense interest in the male genitals, which the therapist attributed to him experiencing the phallic stage of psychosexual development. During this stage, the erogenous zone (the area of the body that one focuses on to derive pleasure) switches to the genitals. At this stage, signs of an Oedipus complex may also be observed, whereby a child competes with their father to retain their position as the central focus of their mother’s affection. Freud believed that this was supported by a fantasy which Little Hans had described, in which a giraffe and another, crumpled, giraffe entered the room. When the boy took the latter from the first giraffe, it objected. Freud believed that the giraffes symbolised his parents - the crumpled giraffe represented his mother, whom he would share a bed with when his father was absent, and the first giraffe was symbolic of his father. Children may also develop castration anxiety resulting from a fear that the father will castrate them in order to remove the threat that they pose to the parents’ relationship.

The boy’s fear of horses, according to Freud, was caused by a displacement of fear for his father onto the animals, whose blinkers made them resemble the man wearing his glasses.

Freud believed that Little Hans’ fear of horses disappeared as his described fantasies that indicated the resolution of his castration anxiety and an acceptance of his love for his mother.

Read more about Little Hans here

Dr. Sergeï Pankejeff (1886-1979) was a client of Sigmund Freud , who referred to him as “Wolf Man” owing to a symbolic dream which he described to him. Freud detailed his sessions with Wolf Man, which commenced in February of 1910, in a 1918 paper entitled From the History of an Infantile Neurosis .

Wolf Man first saw Freud having suffered from deteriorating health since experiencing gonorrhea at the age of eighteen. He described how he was unable to pass bowel movements without the help of an enema, and felt as though he was separated from the rest of the world by a veil.

Freud persuaded Wolf Man to undergo treatment until a set date, after which their sessions should cease, in the belief that his patient would lower his resistance to the therapist’s investigation. Wolf Man agreed, and described to Freud the events of his childhood.

Initially, Wolf Man had been an agreeable child but became combative when his parents returned from their travels. He had been cared for by a new nanny whilst they had been absent and his parents blamed their relationship for his misbehavior. He also recalled developing a fear of wolves, and his sister would taunt him with an illustration in a picture book. However, Wolf Man’s fears extended towards other creatures, including beetles, caterpillars and butterflies. On one occasion, whilst he was pursuing a butterfly, fear overcame him and he was forced to end his pursuit. The man’s conflicting account suggested an early alternation between a phobia of, and taunting of, insects and animals such as horses.

Wolf Man’s unusual behavior was not limited to a fear of animals, and he developed a zealous religious worship routine, kissing every icon in the house before bed time, whilst experiencing blasphemous thoughts.

Wolf Man recalled a dream which had caused him some distress when he had awoken. In the dream, he was laid in bed when he looked out of the window and noticed six or seven white wolves sat in a tree outside. The wolves, which had tails that did not match their bodies, were watching him in his room.

Freud linked this nightmare to a story which Wolf Man’s grandfather had told him, in which a wolf named Reynard lost his tail whilst using it as bait for fishing. He believed that Wolf Man suffered from castration anxiety, which explained the fox-like tails of the wolves in the dream, and his fear of caterpillars, which he used to dissect. The man had also witnessed his father chopping a snake into pieces, which Freud believed had contributed to this anxiety.

Read more about Wolf Man here

The obsessive thoughts of Rat Man were discussed in 1909 paper Notes upon a Case of Obsessional Neurosis . Rat Man’s true identity is unclear, but many believe him to have been Ernst Lanzer (1978-1914), a law graduate of the University of Vienna.

Rat Man suffered from obsessive thoughts for years and underwent hydrotherapy before consulting Freud in 1907, having been impressed by the understanding that the psychoanalyst had professed in his published works. The subject of his thoughts would often involve a sense of anxiety that misfortune would affect a close friend or relative and he felt that he needed to carry out irrational behavior in order to prevent such a mishap from occurring. The irrationality of such thoughts was demonstrated by his fears for the death of his father, which continued even after his father had passed away.

Freud used techniques such as free association in order to uncover repressed memories . Rat Man’s recollection of past events also proved useful to Freud. He described one occasion during his military service, when a colleague revealed to him the morbid details of a torture method that he had learnt of. This form of torture involved placing a container of live rats onto a person and allowing the animals to escape the only way that they could - by burrowing through the victim.

This description stayed with Rat Man and he began to fear that this torture would be imposed upon a relative or friend. He convinced himself that the only way to prevent it would be to pay an officer whom he believed had collected a parcel for him from the post office. When he was prevented from satisfying this need, Rat Man began to feel increasingly anxious until his colleagues agreed to travel to the post office with him in order for the officer to be paid in the order that Rat Man felt was necessary.

Freud attributed Rat Man’s anxieties to a sense of guilt resulting from a repressed desire that he had experienced whilst younger to see women he knew unclothed. As our ego develops, our moral conscience leads us to repress the unreasonable or unacceptable desires of the id , and in the case of Rat Man, these repressed thoughts left behind “ ideational content ” in the conscious. As a result, the subject of anxiety and guilt that he felt whilst younger was replaced with fear of misfortune occurring when he was older.

Read more about Rat Man here

Other Influential Accounts

Whilst Freud saw many clients at his practise in Vienna, and cases such as Wolf Man, Rat Man and Dora are well documented, the psychoanalyst also applied psychodynamic theory to his interpretation of other patients, such Anna O, a client of his friend, Josef Breuer. The autobiographical account of Dr. Daniel Schreber also formed the basis of a 1911 paper by Freud detailing his interpretation of the man’s fantasies.

Anna O (a pseudonym for Austrian feminist Bertha Pappenheim) was a patient of Freud’s close friend, physician Josef Breuer. Although Freud never personally treated her (Anna’s story was relayed to him by Breuer), the woman’s case proved to be influential in the development of his psychodynamic theories. Freud and Breuer published a joint work on hysteria, Studies on Hysteria , in 1895, in which Anna O’s case was discussed.

Seeking treatment from Breur for hysteria in 1880, Anna O experienced paralysis in her right arm and leg, hydrophobia (an aversion to water) which left her unable to drink for long periods, along with involuntary eye movements, including a squint. She also found herself mixing languages whilst speaking to carers and would see hallucinations such as those of black snakes and skeletons, and would wake anxiously from her daytime sleep with cries of “tormenting, tormenting”.

During her talks with Breuer, Anna enjoyed telling fairytale-like stories, which would often involve sitting next to the bedside of a sick person. A dream that she recalled was also of a similar nature: she was sat next to the bed of an ill person in bed when a black snake approached the invalid. Anna wanted to protect the person from the snake but felt paralysed and was unable to warn off the snake.

Freud and Breuer considered the subject of this dream to be linked to an earlier experience. Prior to her own illness, Anna’s father had contracted tuberculosis and she had spent considerable lengths of time caring for him by his bedside. During this period, Anna had fallen ill, preventing her from accompanying her father in his final days and he passed away on April 1881. The trauma of caring for her father may have affected Anna, and Breuer believed that the paralysis she experienced in reality was a result of that which she had experienced in the dream. Furthermore, he linked her hydrophobia to another traumatic event some time previously, when she had witnessed a dog drinking from a glass of water that she was supposed to use. The revulsion she felt had stayed with her and manifested in a later aversion to water.

The conscious realisation of the causes behind her suffering, according to Breuer, helped Anna to make a recovery in 1882. She valued the “talking therapy” that he had provided, describing their sessions as “chimney sweeping”.

Read more about Anna O here

Dr. Daniel Schreber

Freud’s interpretation of client’s past experiences and dreams was not limited to the patients he saw at his Vienna clinic. German judge Dr. Daniel Schreber (1842-1911) wrote a book, Memoirs of My Nervous Illness (1903) - in which he detailed the fantasies that he experienced during the second of three periods of illness - whilst confined in the asylum of Sonnenstein Castle.

Upon reading the book, Freud offered his own thoughts on the causes of Schreber’s fantasies, which were published in his 1911 paper Notes upon an autobiographical account of a case of paranoia (dementia paranoides) .

Initially suffering whilst standing as a candidate in the 1884 Reichstag elections, Schreber had begun to experience hypochondria, for which he sought the help of Professor Paul Flechsig. After six months, treatment ended, but he returned to Flechsig in 1893, bothered again by hypochondria and now sleeplessness also. Schreber recalled thoughts during a half-asleep state in which he noted that “it really must be very nice to be a woman submitting to the act of copulation” (Freud, 1911). He would eventually turn against Professor Flechsig, accusing him of being a “soul murderer”, and thoughts of emasculation also developed into extended fantasies - Schreber convinced himself that he had been assigned a role of savior of the world, and that he must be turned in a woman in order for God to impregnate with him, creating a new generation which would repopulate the planet.

In his response to Schreber’s account, Freud focussed on the religious nature of the fantasies. Whilst Schreber was agnostic, his thoughts suggested religious doubts and what Freud described as “redeemer delusion” - a sense of being elevated to the role of redeemer of the world. The process of emasculation that Schreber felt was necessary was attributed by Freud to “homosexual impulses”, which the psychoanalyst suggests were directed towards the man’s father and brother. However, feelings of guilt for experiencing such desires led to them being repressed.

Freud also understood Schreber’s sense of resentment towards Flechsig in terms of transference - his feelings towards his brother had been subconsciously transferred to the professor, whilst those towards his father had been transferred to a godly figure.

Read more about Daniel Schreber here

Which Archetype Are You?

Are You Angry?

Windows to the Soul

Are You Stressed?

Attachment & Relationships

Memory Like A Goldfish?

31 Defense Mechanisms

Slave To Your Role?

Are You Fixated?

Interpret Your Dreams

How to Read Body Language

How to Beat Stress and Succeed in Exams

More on Freudian Psychology

A look at common defense mechanisms we employ to protect the ego.

31 Psychological Defense Mechanisms Explained

What's your personality type? Find out with this test.

Test Your Freudian Knowledge

Test your knowledge of Sigmund Freud and Freudian psychology with this revision...

Defense Mechanisms Quiz

Test your knowledge of defense mechanisms in psychology with this revision quiz.

The Case Of Little Hans

How Freud used a boy's horse phobia to support his theories.

Sign Up for Unlimited Access

- Psychology approaches, theories and studies explained

- Body Language Reading Guide

- How to Interpret Your Dreams Guide

- Self Hypnosis Downloads

- Plus More Member Benefits

You May Also Like...

Making conversation, nap for performance, psychology of color, dark sense of humor linked to intelligence, brainwashed, persuasion with ingratiation, master body language, why do we dream, psychology guides.

Learn Body Language Reading

How To Interpret Your Dreams

Overcome Your Fears and Phobias

Psychology topics, learn psychology.

- Access 2,200+ insightful pages of psychology explanations & theories

- Insights into the way we think and behave

- Body Language & Dream Interpretation guides

- Self hypnosis MP3 downloads and more

- Behavioral Approach

- Eye Reading

- Stress Test

- Cognitive Approach

- Fight-or-Flight Response

- Neuroticism Test

© 2024 Psychologist World. Home About Contact Us Terms of Use Privacy & Cookies Hypnosis Scripts Sign Up

- Case Report

- Open access

- Published: 21 May 2024

A complex systems perspective on chronic aggression and self-injury: case study of a woman with mild intellectual disability and borderline personality disorder

- Daan H. G. Hulsmans 1 , 2 ,

- Roy Otten 1 ,

- Evelien A. P. Poelen 1 , 2 ,

- Annemarie van Vonderen 2 ,

- Serena Daalmans 1 ,

- Fred Hasselman 1 ,

- Merlijn Olthof 1 , 3 &

- Anna Lichtwarck-Aschoff 3

BMC Psychiatry volume 24 , Article number: 378 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

Challenging behaviors like aggression and self-injury are dangerous for clients and staff in residential care. These behaviors are not well understood and therefore often labeled as “complex”. Yet it remains vague what this supposed complexity entails at the individual level. This case-study used a three-step mixed-methods analytical strategy, inspired by complex systems theory. First, we construed a holistic summary of relevant factors in her daily life. Second, we described her challenging behavioral trajectory by identifying stable phases. Third, instability and extraordinary events in her environment were evaluated as potential change-inducing mechanisms between different phases.

Case presentation

A woman, living at a residential facility, diagnosed with mild intellectual disability and borderline personality disorder, who shows a chronic pattern of aggressive and self-injurious incidents. She used ecological momentary assessments to self-rate challenging behaviors daily for 560 days.

Conclusions

A qualitative summary of caretaker records revealed many internal and environmental factors relevant to her daily life. Her clinician narrowed these down to 11 staff hypothesized risk- and protective factors, such as reliving trauma, experiencing pain, receiving medical care or compliments. Coercive measures increased the chance of challenging behavior the day after and psychological therapy sessions decreased the chance of self-injury the day after. The majority of contemporaneous and lagged associations between these 11 factors and self-reported challenging behaviors were non-significant, indicating that challenging behaviors are not governed by mono-causal if-then relations, speaking to its complex nature. Despite this complexity there were patterns in the temporal ordering of incidents. Aggression and self-injury occurred on respectively 13% and 50% of the 560 days. On this timeline 11 distinct stable phases were identified that alternated between four unique states: high levels of aggression and self-injury, average aggression and self-injury, low aggression and self-injury, and low aggression with high self-injury. Eight out of ten transitions between phases were triggered by extraordinary events in her environment, or preceded by increased fluctuations in her self-ratings, or a combination of these two. Desirable patterns emerged more often and were less easily malleable, indicating that when she experiences bad times, keeping in mind that better times lie ahead is hopeful and realistic.

Peer Review reports

In residential care for individuals with an intellectual disability, challenging behavior is an often used umbrella term for repeatedly engaging in dangerous or threatening behaviors. These can be outer-directed, like aggression towards people or damaging property, and inner-directed, such as self-injurious behavior [ 1 , 2 ]. The latter is defined as inflicting deliberate damage on- or destruction of one’s own body tissue with or without suicidal intent, for example by skin cutting, burning, scratching, or ingesting inedible objects [ 3 ]. For staff, these behaviors are hard to grasp and sometimes difficult to anticipate. Managing incidents afterwards with freedom restricting measures, such as seclusion or fixation, remains an unwanted and increasingly unaccepted common-practice that is harmful to clients and increases staff stress and turnover [ 4 , 5 ]. Staff typically describe challenging behaviors as a way the individual communicates unmet “complex needs” [ 6 ]. Although group-level research reveals many biological, psychological and social correlates of challenging behavior [ 2 , 7 , 8 ], it remains vague what this often-used adjective “complex” means at the individual level. Research focused on the individual rather than on the group can efficiently advance our understanding of complex phenomena [ 9 ]. Therefore, this study provides a unique exploration of patterns of chronic aggressive and self-injurious behaviors in one woman with a mild intellectual disability (MID) and borderline personality disorder (BPD), day-by-day over the course of 560 days.

The overall goal is to obtain an in-depth understanding of when and why challenging behaviors occur, using an analytical strategy inspired by complex systems theory (cf [ 10 ]). This complex systems lens differs from the dominant biomedical perspective on psychopathology. That is, from a complex systems perspective psychiatric disorders are not understood as latent entities that cause symptoms through (relatively static) hard-wired biological mechanisms, but as dynamic patterns of behaviors, emotions and cognitions that are formed over time [ 11 , 12 ]. Complex systems principles have guided individual-specific explorations of dynamics in high-risk young adults [ 13 ], people with depression [ 14 , 15 , 16 ] and dissociative identity disorder [ 17 , 18 ]. While these studies all used quantitative timeseries analyses to describe the dynamics, qualitative methods are just as well-suited within a complex systems framework. Central to complex systems theory is a holistic approach to understand the person in their environment [ 12 ] and qualitative methods can provide a rich account thereof [ 19 ]. The current study therefore offers a holistic and dynamic exploration of a woman with MID and BPD, by employing a mixed-methods strategy with three overarching aims. In the following sections we introduce these three aims step-by-step, with more detailed theoretical background.

Summarizing daily life

The first step is to qualitatively summarize the complex nature of challenging behavior. From a complex systems perspective, any person is considered a complex system, not just individuals with challenging behavior [ 12 ]. It is complex because there is no root cause for the way a person (i.e., system as a whole) feels, thinks, or behaves at certain moments in time. Emotions, thoughts or behaviors emerge from continuous and interdependent exchanges between the system’s internal state and its environment [ 20 ]. Complex systems are everchanging, which is why an integrative understanding requires a detailed description of the interplay between the system’s and context elements over a longer period of time. It is therefore necessary to sample personal experiences and contextual influences frequently over time, for example by making use of ecological momentary assessment (EMA). EMA is a method in which someone frequently self-reports on current or very recent behaviors and experiences over time (typically via mobile-phone) [ 21 ]. The method is well-established in samples with BPD, but although feasible [ 22 ] not often used in MID research. In earlier work involving clients with BPD, momentary self-injury was associated with daily ruminations or heightened negative affect [ 23 ]. Other EMA studies found the intensity of anger associated with daily reports of aggression [ 24 ]. Such internal experiences (i.e., related to thoughts, emotions, or other behaviors) are the primary focus of most EMA research, but there are few studies that explicitly investigate contextual influences and changes [ 23 ]. This is remarkable, because theory indicates that (challenging) behaviors are not only internally driven but are to a large extend elicited by environmental factors [ 12 ]. For instance, self-injury, is known to occur more frequently when experiencing interpersonal stress [ 25 ]. However, internal factors and the environment differs between persons [ 26 , 27 ]. Whereas one person’s self-injury may be triggered by an argument with parents, someone else’s work pressure may trigger it. To obtain a holistic summary of the person-environment interplay, we first explore person-specific internal states and environmental factors qualitatively.

Describing change over time

The second step is to zoom out, quantitatively exploring how these factors are ordered in time on the participant’s 560-day timeline. EMA research typically employs multiple daily self-ratings for 1–3 weeks, but individual accounts of challenging behaviors over longer timeframes are scarce. Some studies used not daily but weekly caretaker-reports of challenging behavioral incidents. These showed that, during a period of 41 weeks, staff of 33 inpatients with MID reported in total 210 aggressive- and 104 self-injurious incidents [ 28 , 29 ]. Interestingly, 4 of those 33 inpatients were responsible for over half of the 210 aggressive incidents, while a staggering 85% of the 104 self-injurious incidents were from only 2 clients. Few individuals thus account for many incidents, but little is known about the day-to-day temporal patterns of such chronic challenging behaviors over the course of weeks or months.

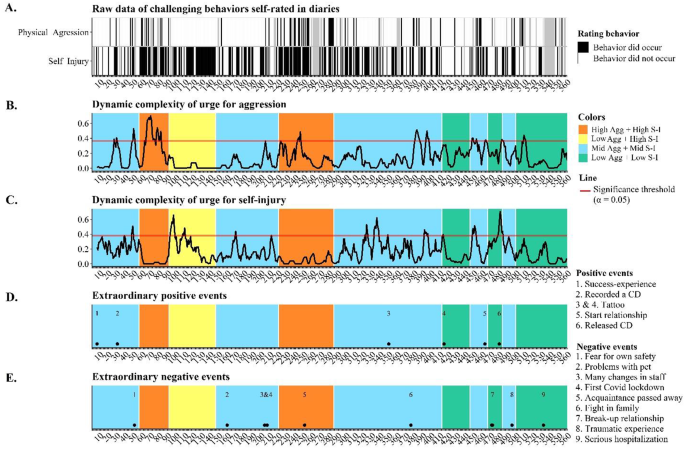

When a person is tracked over longer periods of time, one can detected phases in which certain behaviors are relatively stable. A single-case study using EMA of a person with a major depressive disorder over almost eight months (239 days) [ 15 ] found two distinct phases. The first four months were characterized by consistent low self-reported depressive symptoms. On the 127th day this abruptly changed, marking the start of a four-month period characterized by consistently high depressive symptoms. From a complex systems perspective, these two stable phases (before and after day 127) are called attractors [ 30 ]. That is, the dynamics of the person (i.e., person-environment system) are attracted towards a specific behavioral pattern that remains relatively stable over time (e.g., a depressive phase in this example). Importantly, stability does not speak to the desirableness of the patterns, but only to the consistency of change over time. For example, consistently never self-harming, consistently being aggressive once-per-week on Tuesdays, or consistently self-harming on weekends are all examples of stable patterns. Following complex systems theory, stable patterns of challenging behaviors can thus be understood as attractors [ 11 , 12 ]. Our second research question is how challenging behaviors are ordered on the participant’s 560-day timeline? This is done by identifying if there are different attractor states (e.g. time-periods with relatively few vs. many challenging behaviors) and explicate ways in which these time-periods are (dis)similar from one another in terms of internal states (e.g., experienced emotions) and environmental influences (e.g., social interactions).

Change-mechanisms

In the third and last step we zoom in again by exploring transition-points: moments that ‘kickstart’ abrupt change towards a new attractor (cf. day 127 in [ 15 ]). Complex systems theory posits two general mechanisms for the change from one attractor to another that are relevant in the context of this study.

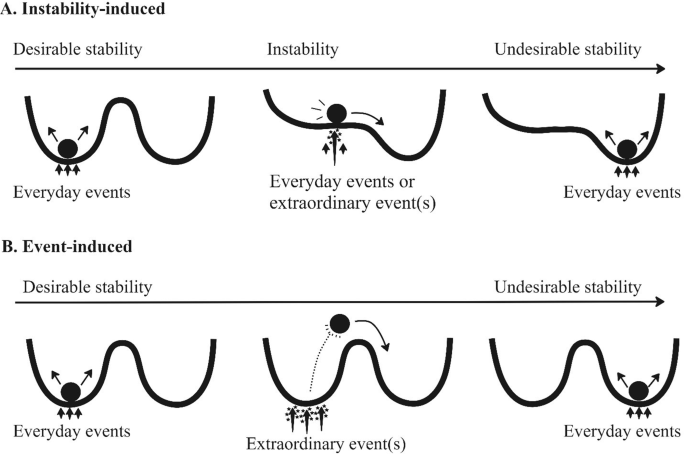

First, instability-induced change (also called bifurcation-induced change [ 31 ]) is the mechanism in which an existing attractor destabilizes, thereby forcing the system to reach a new attractor. In Fig. 1 , someone’s current state (e.g., frequently self-injuring) is visualized as a ball, located in a basin which reflects the attractor. The two basins reflect two example attractors: a pattern of few self-injuring behaviors and a pattern of frequent self-injuring behaviors. The basin’s depth metaphorically represents the strength of the attractor state. Stronger attractors are harder to change and therefore everyday events typically do not trigger enduring change. Figure 1 A shows instability-induced change, in which an existing attractor destabilizes to the extent that there is no valley left to contain the ball, making the ball roll towards a new valley [ 11 , 12 , 32 ]. Note that during instability, the ball can move more ‘freely’ through the valley (as it is less steep), leading to increasingly variable behavior. Measures of temporal complexity and variability can therefore pick up on instability [ 33 , 34 ].

Second, event-induced (also called noise-induced [ 31 ]) change is when an extraordinary event (e.g., unexpectedly being fired from work) ‘pushes’ the ball towards a different attractor, without the existing attractor losing its stability first (Fig. 1 B). One would not expect instability as an early warning signal for the transition in this event-induced change, while one would expect the presence of an extraordinary event [ 12 , 31 ]. This makes it possible to empirically differentiate instability-induced and event-induced changes. The third aim of this study was therefore to evaluate which, if any, of these two change-mechanism(s) potentially underlie transitions between attractors.

Conceptualization of two potential change-mechanisms according to complex systems theory. Possible attractors are visually conceptualized as a landscape with basins. In this example, the left basin reflects a desirable attractor (few self-injury) and right one an undesirable attractor (frequent self-injury). The ball reflects a person’s state at one point in time while arrows below the ball symbolize interactions between person and environment in daily life. The top panel ( A ) reflects a mechanism in which we can observe instability over time. During instability the attractor loses strength, visualized as the basin becoming more shallow. When this happens, interactions between person and environment, however casual or extraordinary, lead to a transition towards another attractor. The bottom panel’s mechanism ( B ) reflects a mechanism in which the attractor itself does not lose strength. Therefore this will not be marked by instability. Everyday events will not be enough to reach a transition. Instead it takes extraordinarily strong environment-person interaction to ‘force’ this change

The participant is a woman in her 30s, diagnosed with MID and BPD. For over a decade, she has lived in a 24-hour residential care facility specialized for people with MID and severe behavioral problems. Her daily routine typically consists of working in the house (e.g., cooking, cleaning), she likes to take walks, and enjoys playing board games. For several days a week she goes to an activity center where she works creatively (e.g., draw paintings, make music), alone or together with others. This provides important structure in her daily routine. Staff is available 24 − 7 to support her. Even seemingly regular tasks, such as arriving in time for appointments, may be perceived as onerous. Staff are therefore reminded to compliment her regularly, even with seemingly trivial accomplishments. She best thrives when she experiences support that is clear and structured, because that makes her feel calm and secure.

Before she lived in the care facility, during her childhood and teenage years, she experienced traumatic events that undoubtedly contributed to challenges she faces nowadays. She often perceives her life as a struggle, some days more than others. She mostly communicates her struggles calmly to others, but sometimes her tensions become explicit to her environment when she self-injures or is physically aggressive. According to her care professionals, her overall well-being is poorer on days when she shows these behaviors. Her care professionals have several hypotheses about factors contributing to her challenging behaviors. One is that she does not trust herself to be alone. The self-injuring and aggressive incidents are, at least sometimes, perceived as a call for reassuring attention from staff. Another hypothesis is that her challenging behaviors are a maladaptive emotion-regulation strategy. Unpleasant emotions can (sometimes unexpectedly) accumulate very rapidly. Over time, she has learned that she can immediately achieve short-term relief from this overwhelming emotional experience by self-injuring. Alternatively, difficulties regulating negative emotions are also considered a cause of aggressive behaviors. After self-injurious or aggressive incidents, staff need to ensure the participant’s and others’ safety, sometimes by imposing freedom restricting measures such as seclusion or fixation. Such drastic measures are resented by staff and the participant alike. She is highly motivated to change her challenging behavioral patterns, and therefore follows dialectical behavior therapy that aims to increase her emotion regulatory abilities [ 35 ].

Procedure and measures

As part of dialectical behavior therapy, the participant completed daily self-registrations via a mobile phone application. Hence, these EMA data were initially not collected for research purposes. The participant and her clinician formulated the application’s daily EMA questions together. Emotions, behaviors and cognitions with maximum relevance to her treatment goals and daily life were translated into questions that the app prompted automatically on her phone at 7:00 PM. Seven of those questions could be answered on a slider with six answer options that ranged between “not feeling at all” and “an intense feeling”. These questions inquired to what extend she (1) felt happy, (2) felt scared, (3) felt sad, (4) felt angry, (5) had the urge to self-injure, (6) thought of death, and (7) had the urge to be aggressive, on that particular day. She also self-rated with either a “yes” or “no” whether she, on that day, (8) had self-injured and (9) had been physically aggressive. The participant followed dialectical behavior therapy from mid-2019 until mid-2021, which consisted of weekly group sessions with other clients, one-on-one sessions with a therapist and 24-hour telephone consultation. During these individual sessions, therapist and participant discussed recent self-injurious and aggressive incidents registered in the diary. The participant continued to complete her self-ratings on a daily basis, even when therapy was paused due to Covid-19 restrictions. This was not because she was told to – she felt that she benefitted from daily self-reflections in the app. In total, she completed her diaries for a period of 560 days and was rewarded with a gift card for her long-term dedication.

Informed consent was obtained from the participant and her legal guardian to (1) present and analyze the aforementioned daily diary entries and (2) to access the records (i.e., electronic client files) to perform supplementary qualitative analyses about therapeutical context and care professional’s perspective on her functioning. This electronic health system is a routine procedure in which care professionals describe multiple times per day, the provided care, implemented measures and any relevant daily events concerning the participant. The records of the 560-day self-rating period were retrieved and any information that could be traced back (names of persons, cities, organizations, locations) were replaced by codes such ‘Person A’ or ‘City B’. Her clinical team (clinician and closest care professionals) approved aforementioned procedures beforehand. The Ethical Committee Social Sciences of Radboud University and the Ethics committee of the care organization judged that the research was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

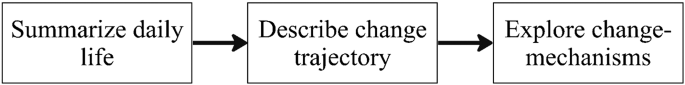

Visualization of our three-step-approach to this case-study

We employed a mixed-methods triangulation design study with both qualitative and quantitative data [ 36 ]. The study had a three-step approach based on complex systems theory (Fig. 2 ). First, we obtained a comprehensive summary of the participant’s daily life through qualitative analyses of the daily caretaker records. These qualitative findings were then quantified, to then be integrated with quantitative daily self-reports. Secondly, we described the trajectory of her self-reported challenging behaviors by identifying transition-points and characterizing the different attractor states. Thirdly, we evaluated transition between attractor states in terms of (in)stability and extraordinary events (cf. Figure 1 ).

Analytical strategy

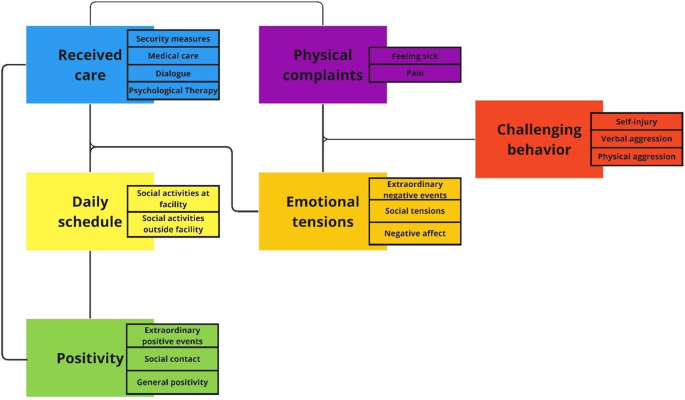

The first step was to qualitatively analyze the anonymized daily records in accordance with the phased approach of thematic analysis [ 19 ]. This thematic analysis was conducted by the first author together with four Master’s students in Pedagogical Sciences, all under the supervision of a researcher with ample experience in qualitative methods. A thematic analysis is an inductive method whereby the coders collaboratively construct themes and patterns from the text in an iterative process that contains six phases: data familiarization, generating initial codes, searching for themes, reviewing themes, defining themes, and producing the research report. In each of these phases, the coders frequently came together to discuss and interpret the records. All five coders first familiarized themselves with the data by reading the whole daily records text file, which consisted of > 300,000 words. Together the coders then practiced the initial coding. The text file was then divided into five roughly equally large chunks of daily records text. Each coder then generated initial codes on his/her own text. The coding was done using MAXQDA 2022 [ 37 ]. During the initial code generating phase, coders came together thrice to compare each other’s initial coding wording and interpretation of the text. These iterative consensus-building sessions lead to the construction of a preliminary overview of candidate subthemes and themes (i.e., codes that were interpreted as reflecting the same higher-order construct). During this collaborative, inductive process, the wording and structure of these (sub)themes were refined into one thematic overview that contained a theme- and subtheme-structure that captured themes based on the whole dataset. This procedure fosters a shared understanding among all coders, resulting in a consensus over the overarching thematic structure (thematic map). From this jointly construed thematic map, every coder then coded the records once more from scratch. That finally resulted in a MAXQDA file with fragments of coded text on a specific day. These qualitative data were then quantified to a dataset containing only binary variables with a (sub)theme coding present (1) or not present (0) per day.

The researcher then met with the participant’s clinician, who has known her for over a decade, to discuss the thematic overview and underlying codes. The goal of this meeting with the clinician was to (1) ascertain the appropriateness of challenging behaviors as the most indicatory variables to summarize the system’s overall state, and (2) identify the most relevant (sub)themes for explaining the frequency of challenging behavioral incidents at any given period.

Describing change trajectory

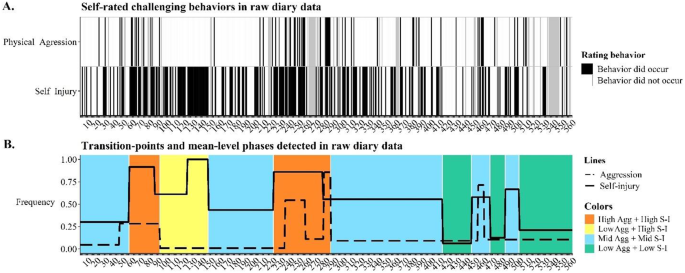

The subsequent steps were quantitative analyses – all performed in RStudio-2022.02.2–458 [ 38 ] which runs on R software version 4.2.0 [ 39 ]. To evaluate concurrent validity of self-ratings, we performed χ 2 tests between self-ratings and informant-reported (daily records) accounts of days with self-injury and physical aggression. Kazdin [ 40 ] recommends evaluating single-case timelines by combining visual inspections of graphed timeseries with statistical analyses. We therefore visualized the two self-report timeseries (physical aggression and self-injury) using functionality from ggplot2 [ 41 ].

Next, we pinpointed transitions in the physical aggression and self-injury timeseries on the 560-day timeline. This transition-point detection was done with the ts_levels function from package casnet [ 42 ], which uses recursive partitioning [ 43 ] to classify segments (or phases) on a timeseries with a relatively stable mean. We did this for the physical aggression and self-injury variables. Because these two variables are binary (0 = behavior did not occur on that day; 1 = behavior occurred on that day), mean levels effectively reflected the proportion of days with incidents within a phase. In the ts_levels function the minimum duration of one phase was set to seven days, comprising a whole weekly routine, and controlling for day-of-the-week effects. The absolute change criterion was set to 25%, meaning that each identified transition reflected at least a 25% increase or decrease compared to the mean of the preceding phase (cf [ 44 , 45 ]). Based on suggestions by Kazdin [ 40 ], we searched for transitions by visually inspecting a graph of the raw binary timeseries and a plot of the levels identified using the ts_levels function [ 42 ].

After pinpointing transitions, we characterized the different attractor states in terms of what makes them (dis)similar from one another on the 560-day timeline. We calculated – per phase and across the whole 560-day timeline – the mean frequency of self-rated challenging behaviors (i.e., mean days with challenging behaviors) and the mean frequencies of (sub)themes that the participant’s clinician hypothesized to be explanatory. Furthermore, we examined – per phase and across the whole 560-day timeline – whether these clinically relevant (sub)themes were associated with challenging behaviors. That is, Fisher’s exact tests evaluated whether a reported challenging behavior occurred (beyond chance) on the same days as reports of staff-hypothesized risk- or protective factors. Additionally, we performed Fisher’s exact tests to evaluate the relation between staff-hypothesized risk- or protective factors from one day until the next (lag-1 association). Due to the number of repeated bivariate associations we evaluated significance at p < 0.01.