Exploring Equity: Race and Ethnicity

- Posted February 18, 2021

- By Gianna Cacciatore

- Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion

- Inequality and Education Gaps

- Moral, Civic, and Ethical Education

- Teachers and Teaching

The history of education in the United States is rife with instances of violence and oppression along lines of race and ethnicity. For educators, leading conversations about race and racism is a challenging, but necessary, part of their work.

“Schools operate within larger contexts: systems of race, racism, and white supremacy; systems of migration and ethnic identity formation; patterns of socialization; the changing realities of capitalism and politics,” explains historian and Harvard lecturer Timothy Patrick McCarthy , co-faculty lead of Race and Ethnicity in Context, a new module offered at the Harvard Graduate School of Education this January as part of a pilot of HGSE’s Equity and Opportunity Foundations course. “How do we understand the role that racial and ethnic identity play with respect to equity and opportunity within an educational context?”

>> Learn more about Equity and Opportunity and HGSE’s other foundational learning experiences.

For educators exploring question in their own homes, schools, and communities, McCarthy and co-faculty lead Ashley Ison, an HGSE doctoral student, offer five ways to get started.

1. Begin with the self.

Practitioners enter conversations about race and racism from different backgrounds, with different lived experiences, personal and professional perspectives, and funds of knowledge in their grasps. Given diverse contexts and realities, it is important that leaders encourage personal transformation and growth. Educators should consider how race and racism, as well as racial and ethnic identity formation, impact their lives as educational professionals, as parents, and as policymakers – whatever roles they hold in society. “This is personal work, but that personal work is also political work,” says Ison.

2. Model vulnerability.

Entering into discussions of race and racism can be challenging, even for those with experience in this work. A key part of enabling participants to lean into the challenge is being vulnerable. “You have trust your students,” explains McCarthy. “Part of that is modeling authentic vulnerability and proximity to the work.” This can be done by modeling discussion skills, like sharing the space and engaging directly with the comments of other participants, as well as by opening up personally to participants.

“Fear can impact how people feel talking about race and ethnicity in an inter-group space,” says Ison. Courage, openness, and trust are key to overcoming that fear and enabling listening, which ultimately allows for critical thinking and change.

3. Be transparent.

Part of being vulnerable is being fully transparent with your students from day one. “Intentions are important,” explains McCarthy. “The gap between intention and impact is often rooted in a lack of transparency about where you’re coming from or where you are hoping to go.”

4. Center voices of color.

Voice and story are powerful tools in this work. Leaders must consider whose voices and stories take precedence on the syllabus. “Consider highlighting authors of color, in particular, who are thinking and writing about these issues,” says Ison. Becoming familiar with a variety of perspectives can help practitioners understand the voices and ideas that exist, she explains.

“Voice and storytelling can bear witness to the various kinds of systematic injustices and inequities we are looking at, but they also function as sources of power for imagining and reimagining the world we are trying to build, all while providing a deeper knowledge of the world as it has existed historically,” adds McCarthy.

5. Prioritize discussion and reflection.

Since this work is as much about critical thinking as it is about content, it is important for educators to make space for discussion and reflection, at the whole-class, small-group, and individual levels. Ison and McCarthy encourage educators to allow students to generate and guide the discussion of predetermined course materials. They also recommend facilitating small group reflections that may spark conversation that can extend into other spaces outside of the classroom.

Selected Resources:

- Poor, but Privileged

- NPR: "The Importance of Diversity in Teaching Staff”

- TED Talk with Clint Smith: "The Danger of Silence"

More Stories from the Series:

- Exploring Equity: Citizenship and Nationality

- Exploring Equity: Gender and Sexuality

- Exploring Equity: Dis/ability

- Exploring Equity: Class

Usable Knowledge

Connecting education research to practice — with timely insights for educators, families, and communities

Related Articles

Navigating Tensions Over Teaching Race and Racism

Disrupting Whiteness in the Classroom

Talking About Race in Mostly White Schools

Bridging the divide by giving young people an entry point into the painful realities of race in America

This is what the racial education gap in the US looks like right now

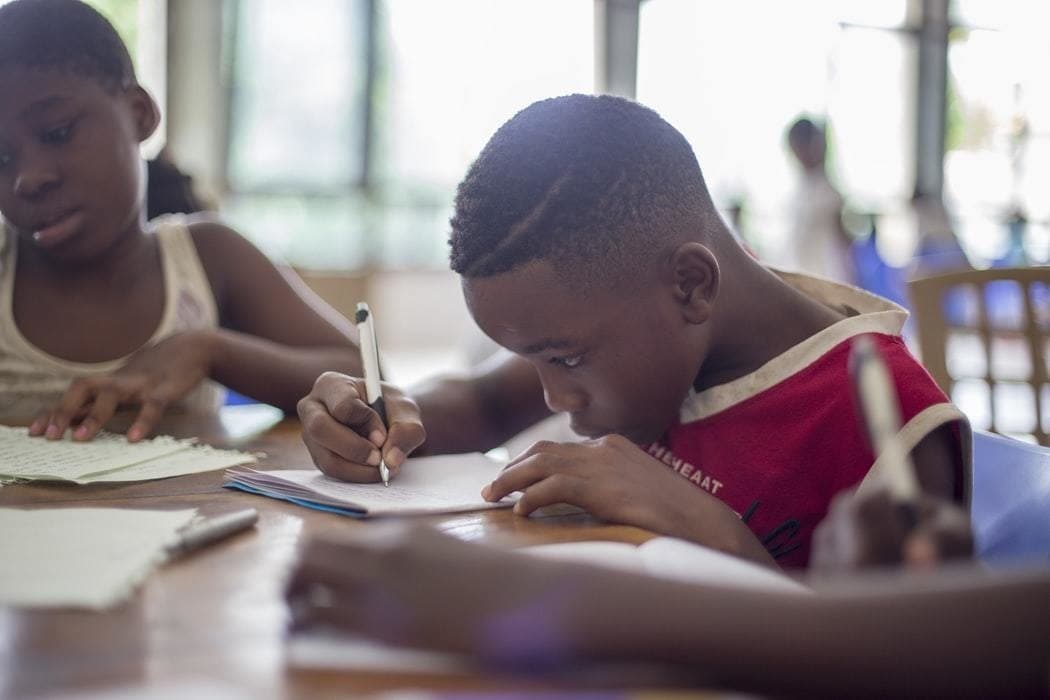

Racial achievement gaps in the United States has been slow and unsteady. Image: Unsplash/Santi Vedrí

.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo{-webkit-transition:all 0.15s ease-out;transition:all 0.15s ease-out;cursor:pointer;-webkit-text-decoration:none;text-decoration:none;outline:none;color:inherit;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:hover,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-hover]{-webkit-text-decoration:underline;text-decoration:underline;}.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo:focus,.chakra .wef-1c7l3mo[data-focus]{box-shadow:0 0 0 3px rgba(168,203,251,0.5);} David Elliott

.chakra .wef-9dduvl{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-9dduvl{font-size:1.125rem;}} Explore and monitor how .chakra .wef-15eoq1r{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-size:1.25rem;color:#F7DB5E;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-15eoq1r{font-size:1.125rem;}} Education, Gender and Work is affecting economies, industries and global issues

.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;color:#2846F8;font-size:1.25rem;}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-1nk5u5d{font-size:1.125rem;}} Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:, education, gender and work.

- Racial achievement gaps in the United States are narrowing, a Stanford University data project shows.

- But progress has been slow and unsteady – and gaps are still large across much of the country.

- COVID-19 could widen existing inequalities in education.

- The World Economic Forum will be exploring the issues around growing income inequality as part of The Jobs Reset Summit .

In the United States today, the average Black and Hispanic students are about three years ahead of where their parents were in maths skills.

They’re roughly two to three years ahead of them in reading, too.

And while white students’ test scores in these subjects have also improved, they’re not rising by as much. This means racial achievement gaps – a key way of monitoring whether all students have access to a good education – in the country are narrowing, research by Stanford University shows.

But while the trend suggests progress is being made in improving racial educational disparities, it doesn’t show the full picture. Progress, the university says, has been slow and uneven.

Have you read?

How can africa prepare its education system for the post-covid world, higher education: do we value degrees in completely the wrong way, this innovative solution is helping indian children get an education during the pandemic.

Standardized tests

Stanford’s Educational Opportunity Monitoring Project uses average standardized test scores for nine-, 13- and 17-year-olds to measure these achievement gaps.

It’s able to do this because the same tests have been used by the National Assessment of Educational Progress to observe maths and reading skills since the 1970s.

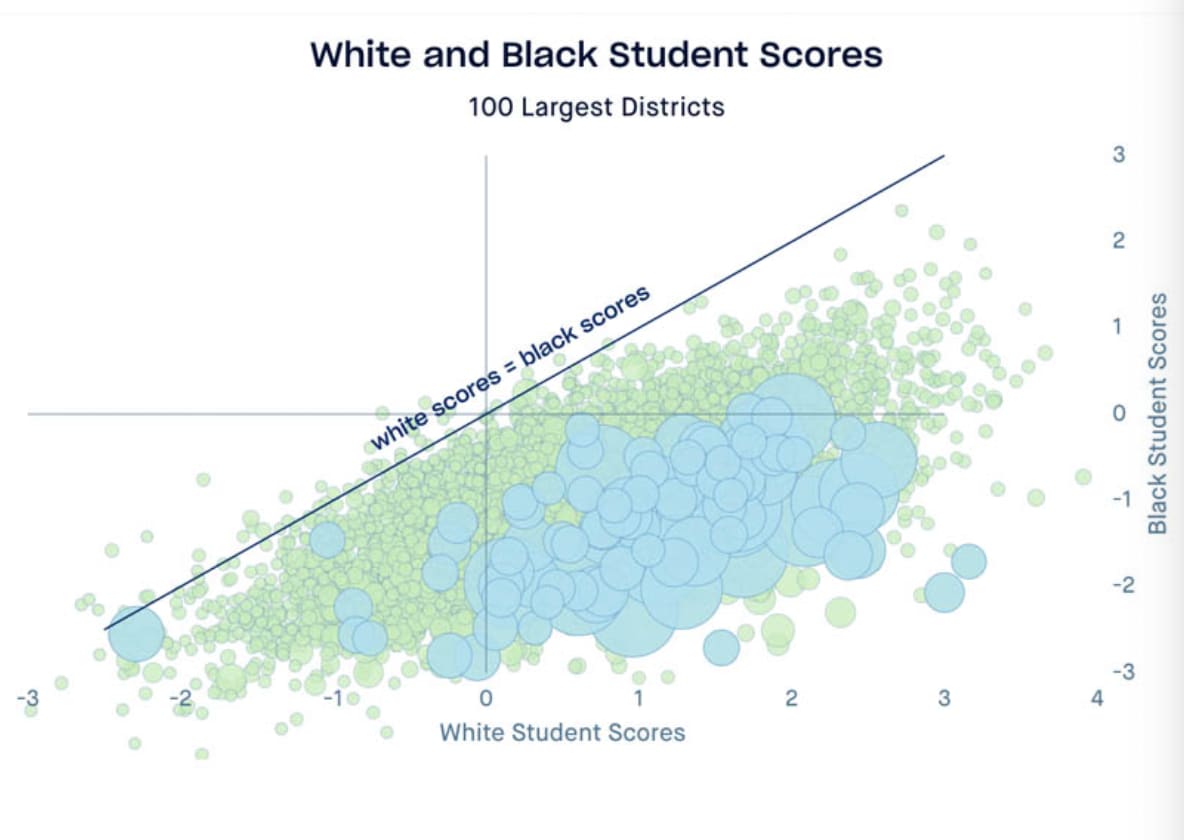

In the following decades, as the above chart shows, achievement gaps have significantly declined in all age groups and in both maths and reading. But it’s been something of a roller-coaster.

Substantial progress stalled at the end of the 1980s and throughout the 1990s and in some cases the gaps grew larger. Since then, they’ve been declining steadily and are now significantly smaller than they were in the 1970s.

But these gaps are still “very large”. In fact, the difference in standardized test scores between white and Black students currently amounts to roughly two years of education. And the gap between white and Hispanic students is almost as big.

Schools not to blame

This disparity exists across the US. Racial achievement gaps have narrowed in most states – although they’ve widened in a small number. In almost all of the country’s 100 largest school districts , though, there’s a big achievement gap between white and Black students.

So why is this? Stanford says its data doesn’t support the common argument that schools themselves are to blame for low average test scores, which is often made because white students tend to live in wealthier communities where schools are presumed to be better.

In fact, it says, the scores actually represent gaps in educational opportunity, which can be traced back to a child’s early experiences. These experiences are formed at home, in childcare and preschool, and in communities – and they provide opportunities to develop socioemotional and academic capacities.

Higher-income families are more likely to be able to provide these opportunities to their children, so a family’s socioeconomic resources are strongly related to educational outcomes , Stanford says. It notes that in the US, Black and Hispanic children’s parents typically have lower incomes and levels of educational attainment than those of white children.

Other factors, such as patterns of residential and school segregation and a state’s educational and social policies, could also have a role in the size of achievement gaps.

And discipline could play its part, too, according to another Stanford study. It linked the achievement gap between Black and white students to the fact that the former are punished more harshly for similar misbehaviour, for example being more likely to be suspended from school than the latter.

Long-term effects

Stanford says using data to map race and poverty could provide the insights needed to help improve educational opportunity for all children.

And this kind of insight is needed now more than ever. The school shutdowns forced by COVID-19 could have exacerbated existing achievement gaps , according to research from McKinsey. The consultancy says the resulting learning losses – predicted to be greater for low-income Black and Hispanic students – could have long-term effects on the economic well-being of the affected children.

Black and Hispanic families are less likely to have high-speed internet at home, making distance learning difficult. And students living in low-income neighbourhoods are less likely to have had decent home schooling, according to the Economic Policy Institute. Earlier in the pandemic, it said coronavirus would "explode" achievement gaps , suggesting it could expand them by the equivalent of another half a year of schooling.

The World Economic Forum’s Jobs Reset Summit brings together leaders from business, government, civil society, media and the broader public to shape a new agenda for growth, jobs, skills and equity.

The two-day virtual event, being held on 1-2 June 2021, will address the most critical areas of debate, articulate pathways for action, and mobilize the most influential leaders and organizations to work together to accelerate progress.

The Summit will develop new frameworks, shape innovative solutions and accelerate action on four thematic pillars: Economic Growth, Revival and Transformation; Work, Wages and Job Creation; Education, Skills and Lifelong Learning; and Equity, Inclusion and Social Justice.

The World Economic Forum will be exploring the issues around growing income inequality, and what to do about it, as part of The Jobs Reset Summit .

The summit will look at ways to shape more inclusive, fair and sustainable organizations, economies and societies as we emerge from the current crisis.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

The agenda .chakra .wef-n7bacu{margin-top:16px;margin-bottom:16px;line-height:1.388;font-weight:400;} weekly.

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

.chakra .wef-1dtnjt5{display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;} More on Education and Skills .chakra .wef-17xejub{-webkit-flex:1;-ms-flex:1;flex:1;justify-self:stretch;-webkit-align-self:stretch;-ms-flex-item-align:stretch;align-self:stretch;} .chakra .wef-nr1rr4{display:-webkit-inline-box;display:-webkit-inline-flex;display:-ms-inline-flexbox;display:inline-flex;white-space:normal;vertical-align:middle;text-transform:uppercase;font-size:0.75rem;border-radius:0.25rem;font-weight:700;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;line-height:1.2;-webkit-letter-spacing:1.25px;-moz-letter-spacing:1.25px;-ms-letter-spacing:1.25px;letter-spacing:1.25px;background:none;padding:0px;color:#B3B3B3;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;box-decoration-break:clone;-webkit-box-decoration-break:clone;}@media screen and (min-width:37.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:0.875rem;}}@media screen and (min-width:56.5rem){.chakra .wef-nr1rr4{font-size:1rem;}} See all

How focused giving can unlock billions and catapult women’s wealth

Mark Muckerheide

May 21, 2024

AI is changing the shape of leadership – how can business leaders prepare?

Ana Paula Assis

May 10, 2024

From virtual tutors to accessible textbooks: 5 ways AI is transforming education

Andrea Willige

These are the top ranking universities in Asia for 2024

May 8, 2024

Globally young people are investing more than ever, but do they have the best tools to do so?

Hallie Spear

May 7, 2024

Reskilling Revolution: The Role of AI in Education 4.0

Researching Race and Ethnic Inequalities in Education. Key Findings and Future Directions

- First Online: 06 July 2019

- pp 1237–1270

Cite this chapter

- Peter A. J. Stevens 3 &

- A. Gary Dworkin 4

2309 Accesses

As pointed out in the introduction, the sheer scope of the research discussed in this Handbook does not allow us to integrate critically all the findings that emerged out of these studies into a single concluding chapter that advises on future directions for research in each of the key research traditions and national and regional contexts. Instead in this concluding chapter we aim to realize three goals. First, we summarize and discuss some of the key characteristics of each national/regional review presented in an overview grid, which includes information on the: (1) research traditions; (2) research goals; (3) dominant research designs; (4) focus on groups identified as racially or ethnically distinct; (5) relationship between policy-makers and the research community; (6) key policy characteristics and developments over time; and (7) main language(s) of publication. This overview grid is used both as a tool to summarize research conducted in this area and as a reference guide that can be used by readers to identify particular areas of research and information and as a result assist in developing more specific, integrative reviews.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Bibliograpy

Ball, S. J., Maguire, M., & Braun, A. (2012). How Schools Do Policy: Policy Enactments in Secondary Schools . London: Routledge.

Google Scholar

Banks, J. A. (1993). Multicultural Education: Histrorical Development, Dimensions, and Practice. Review of Research in Education, 19 (1), 3–49.

Article Google Scholar

Banton, M. (1967). Race Relations . New York: Basic Books.

Brubaker, R. (2004). Ethnicity Without Groups . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Book Google Scholar

Carter, B., & Fenton, S. (2009). Not Thinking Ethnicity: A Critique of the Ethnicity Paradigm in an Over-Ethnicised Sociology. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 40 , 1–18.

Delamont, S. (Ed.). (1977). Readings on Interactionism in the Classroom: Contemporary Sociology of the School . London/New York: Methuen.

Dworkin, A. G., & Dworkin, R. J. (1999). The Minority Report . New York: Harcourt Brace Publishers.

Foster, P., Gomm, R., & Hammersley, M. (1996). Constructing Educational Inequality: An Assessment of Research on School Processes . London: Falmer.

Gamoran, A., & Berends, M. (1987). The Effects of Stratification in Secondary Schools: Synthesis of Survey and Ethnographic Research. Review of Educational Research, 57 , 415–435.

Green, A., Preston, J., & Janmaat, J. G. (2006). Education, Equality, and Social Cohesion: A Comparative Analysis . Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Hammersley, M., & Woods, P. (1984). Life in School: The Sociology of Pupil Culture . Milton Keynes: Open University Press.

Hargreaves, A., & Woods, P. (1984). Classrooms and Staffrooms: The Sociology of Teachers and Teaching . Milton Keynes: Open University Press.

Jacobs, D., Rea, A., Teney, C., Callier, L., & Lothaire, S. (2009). De sociale lift blijft steken. De prestaties van allochtone leerlingen in de Vlaamse Gemeenschap en de Franse Gemeenschap . De Koning Boudewijnstichting: Brussels.

Lamont, M., & Mizrachi, N. (2012). Ordinary People Doing Extraordinary Things: Responses to Stigmatization in Comparative Perspective. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 35 , 365–381.

Pigozzi, M. J. (2006). What Is the Quality of Education? (A UNESCO Perspective. In K. N. Ross &. I. J. Genevois (Eds.), Cross-National Studies of the Quality of Education: Planning Their Design and Managing Their Impact (pp. 39–50). Paris: UNESCO: International Institute for Educational Planning. http://www.unesco.org/iiep

Pinterits, E. J., Spanierman, L. B., & Poteat, P. V. (2009). The White Privilege Attitudes Scale: Development and Initial Validation. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 56 , 417–429.

Prokic-Breuer, T., & Dronkers, J. (2011). Highly Differentiated but Still Not the Same Results: Explaining Differences in Educational Achievement Between Highly Differentiated Educational Systems with General and Vocational Training . Onderwijsresearchdagen: University of Maastricht (Netherlands).

Quillian, L. (2006). New Approaches to Understanding Racial Prejudice and Discrimination. Annual Review of Sociology, 32 , 299–328.

Stevens, P. A. J., & Van Houtte, M. (2011). Adapting to the System or the Student? Exploring Teacher Adaptations to Disadvantaged Students in an English and Belgian Secondary School. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 33 (1), 59–75.

Van Den Berghe, P. (1967). Race and Racism: A Comparative Perspective . New York: Wiley.

Van Houtte, M. (2004). Tracking Effects on School Achievement: A Quantitative Explanation in Terms of the Academic Culture of School Staff. American Journal of Education, 110 , 354–388.

Vervaet, Roselien. (2018). Ethnic Prejudice Among Flemish Pupils: Does the School Context Matter? (Unpublished PhD Thesis). Department of Sociology, Ghent University.

Woods, P. (1990). The Happiest Days? How Pupils Cope with School . London/New York: The Falmer Press.

Woods, P., & Hammersley, M. (Eds.). (1977). School Experience. Explorations in the Sociology of Education . New York: St Martin’s Press.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Sociology, Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium

Peter A. J. Stevens

Department of Sociology, The University of Houston, Houston, TX, USA

A. Gary Dworkin

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Peter A. J. Stevens .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations, rights and permissions.

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 The Author(s)

About this chapter

Stevens, P.A.J., Dworkin, A.G. (2019). Researching Race and Ethnic Inequalities in Education. Key Findings and Future Directions. In: Stevens, P.A.J., Dworkin, A.G. (eds) The Palgrave Handbook of Race and Ethnic Inequalities in Education. Palgrave Macmillan, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-94724-2_29

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-94724-2_29

Published : 06 July 2019

Publisher Name : Palgrave Macmillan, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-319-94723-5

Online ISBN : 978-3-319-94724-2

eBook Packages : Education Education (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Unequal Opportunity: Race and Education

Subscribe to governance weekly, linda darling-hammond ld linda darling-hammond.

March 1, 1998

- 13 min read

W.E.B. DuBois was right about the problem of the 21st century. The color line divides us still. In recent years, the most visible evidence of this in the public policy arena has been the persistent attack on affirmative action in higher education and employment. From the perspective of many Americans who believe that the vestiges of discrimination have disappeared, affirmative action now provides an unfair advantage to minorities. From the perspective of others who daily experience the consequences of ongoing discrimination, affirmative action is needed to protect opportunities likely to evaporate if an affirmative obligation to act fairly does not exist. And for Americans of all backgrounds, the allocation of opportunity in a society that is becoming ever more dependent on knowledge and education is a source of great anxiety and concern.

At the center of these debates are interpretations of the gaps in educational achievement between white and non-Asian minority students as measured by standardized test scores. The presumption that guides much of the conversation is that equal opportunity now exists; therefore, continued low levels of achievement on the part of minority students must be a function of genes, culture, or a lack of effort and will (see, for example, Richard Herrnstein and Charles Murray’s The Bell Curve and Stephan and Abigail Thernstrom’s America in Black and White).

The assumptions that undergird this debate miss an important reality: educational outcomes for minority children are much more a function of their unequal access to key educational resources, including skilled teachers and quality curriculum, than they are a function of race. In fact, the U.S. educational system is one of the most unequal in the industrialized world, and students routinely receive dramatically different learning opportunities based on their social status. In contrast to European and Asian nations that fund schools centrally and equally, the wealthiest 10 percent of U.S. school districts spend nearly 10 times more than the poorest 10 percent, and spending ratios of 3 to 1 are common within states. Despite stark differences in funding, teacher quality, curriculum, and class sizes, the prevailing view is that if students do not achieve, it is their own fault. If we are ever to get beyond the problem of the color line, we must confront and address these inequalities.

The Nature of Educational Inequality

Americans often forget that as late as the 1960s most African-American, Latino, and Native American students were educated in wholly segregated schools funded at rates many times lower than those serving whites and were excluded from many higher education institutions entirely. The end of legal segregation followed by efforts to equalize spending since 1970 has made a substantial difference for student achievement. On every major national test, including the National Assessment of Educational Progress, the gap in minority and white students’ test scores narrowed substantially between 1970 and 1990, especially for elementary school students. On the Scholastic Aptitude Test (SAT), the scores of African-American students climbed 54 points between 1976 and 1994, while those of white students remained stable.

Related Books

Tom Loveless

October 22, 2000

Dick Startz

January 15, 2019

Michael Hansen, Diana Quintero

July 10, 2018

Even so, educational experiences for minority students have continued to be substantially separate and unequal. Two-thirds of minority students still attend schools that are predominantly minority, most of them located in central cities and funded well below those in neighboring suburban districts. Recent analyses of data prepared for school finance cases in Alabama, New Jersey, New York, Louisiana, and Texas have found that on every tangible measure—from qualified teachers to curriculum offerings—schools serving greater numbers of students of color had significantly fewer resources than schools serving mostly white students. As William L. Taylor and Dianne Piche noted in a 1991 report to Congress: Inequitable systems of school finance inflict disproportionate harm on minority and economically disadvantaged students. On an inter-state basis, such students are concentrated in states, primarily in the South, that have the lowest capacities to finance public education. On an intra-state basis, many of the states with the widest disparities in educational expenditures are large industrial states. In these states, many minorities and economically disadvantaged students are located in property-poor urban districts which fare the worst in educational expenditures (or) in rural districts which suffer from fiscal inequity.

Jonathan Kozol s 1991 Savage Inequalities described the striking differences between public schools serving students of color in urban settings and their suburban counterparts, which typically spend twice as much per student for populations with many fewer special needs. Contrast MacKenzie High School in Detroit, where word processing courses are taught without word processors because the school cannot afford them, or East St. Louis Senior High School, whose biology lab has no laboratory tables or usable dissecting kits, with nearby suburban schools where children enjoy a computer hookup to Dow Jones to study stock transactions and science laboratories that rival those in some industries. Or contrast Paterson, New Jersey, which could not afford the qualified teachers needed to offer foreign language courses to most high school students, with Princeton, where foreign languages begin in elementary school.

Even within urban school districts, schools with high concentrations of low-income and minority students receive fewer instructional resources than others. And tracking systems exacerbate these inequalities by segregating many low-income and minority students within schools. In combination, these policies leave minority students with fewer and lower-quality books, curriculum materials, laboratories, and computers; significantly larger class sizes; less qualified and experienced teachers; and less access to high-quality curriculum. Many schools serving low-income and minority students do not even offer the math and science courses needed for college, and they provide lower-quality teaching in the classes they do offer. It all adds up.

What Difference Does it Make?

Since the 1966 Coleman report, Equality of Educational Opportunity, another debate has waged as to whether money makes a difference to educational outcomes. It is certainly possible to spend money ineffectively; however, studies that have developed more sophisticated measures of schooling show how money, properly spent, makes a difference. Over the past 30 years, a large body of research has shown that four factors consistently influence student achievement: all else equal, students perform better if they are educated in smaller schools where they are well known (300 to 500 students is optimal), have smaller class sizes (especially at the elementary level), receive a challenging curriculum, and have more highly qualified teachers.

Minority students are much less likely than white children to have any of these resources. In predominantly minority schools, which most students of color attend, schools are large (on average, more than twice as large as predominantly white schools and reaching 3,000 students or more in most cities); on average, class sizes are 15 percent larger overall (80 percent larger for non-special education classes); curriculum offerings and materials are lower in quality; and teachers are much less qualified in terms of levels of education, certification, and training in the fields they teach. And in integrated schools, as UCLA professor Jeannie Oakes described in the 1980s and Harvard professor Gary Orfield’s research has recently confirmed, most minority students are segregated in lower-track classes with larger class sizes, less qualified teachers, and lower-quality curriculum.

Research shows that teachers’ preparation makes a tremendous difference to children’s learning. In an analysis of 900 Texas school districts, Harvard economist Ronald Ferguson found that teachers’ expertise—as measured by scores on a licensing examination, master’s degrees, and experienc—was the single most important determinant of student achievement, accounting for roughly 40 percent of the measured variance in students’ reading and math achievement gains in grades 1-12. After controlling for socioeconomic status, the large disparities in achievement between black and white students were almost entirely due to differences in the qualifications of their teachers. In combination, differences in teacher expertise and class sizes accounted for as much of the measured variance in achievement as did student and family background (figure 1).

Ferguson and Duke economist Helen Ladd repeated this analysis in Alabama and again found sizable influences of teacher qualifications and smaller class sizes on achievement gains in math and reading. They found that more of the difference between the high- and low-scoring districts was explained by teacher qualifications and class sizes than by poverty, race, and parent education.

Meanwhile, a Tennessee study found that elementary school students who are assigned to ineffective teachers for three years in a row score nearly 50 percentile points lower on achievement tests than those assigned to highly effective teachers over the same period. Strikingly, minority students are about half as likely to be assigned to the most effective teachers and twice as likely to be assigned to the least effective.

Minority students are put at greatest risk by the American tradition of allowing enormous variation in the qualifications of teachers. The National Commission on Teaching and America’s Future found that new teachers hired without meeting certification standards (25 percent of all new teachers) are usually assigned to teach the most disadvantaged students in low-income and high-minority schools, while the most highly educated new teachers are hired largely by wealthier schools (figure 2). Students in poor or predominantly minority schools are much less likely to have teachers who are fully qualified or hold higher-level degrees. In schools with the highest minority enrollments, for example, students have less than a 50 percent chance of getting a math or science teacher with a license and a degree in the field. In 1994, fully one-third of teachers in high-poverty schools taught without a minor in their main field and nearly 70 percent taught without a minor in their secondary teaching field.

Studies of underprepared teachers consistently find that they are less effective with students and that they have difficulty with curriculum development, classroom management, student motivation, and teaching strategies. With little knowledge about how children grow, learn, and develop, or about what to do to support their learning, these teachers are less likely to understand students’ learning styles and differences, to anticipate students’ knowledge and potential difficulties, or to plan and redirect instruction to meet students’ needs. Nor are they likely to see it as their job to do so, often blaming the students if their teaching is not successful.

Teacher expertise and curriculum quality are interrelated, because a challenging curriculum requires an expert teacher. Research has found that both students and teachers are tracked: that is, the most expert teachers teach the most demanding courses to the most advantaged students, while lower-track students assigned to less able teachers receive lower-quality teaching and less demanding material. Assignment to tracks is also related to race: even when grades and test scores are comparable, black students are more likely to be assigned to lower-track, nonacademic classes.

When Opportunity Is More Equal

What happens when students of color do get access to more equal opportunities’ Studies find that curriculum quality and teacher skill make more difference to educational outcomes than the initial test scores or racial backgrounds of students. Analyses of national data from both the High School and Beyond Surveys and the National Educational Longitudinal Surveys have demonstrated that, while there are dramatic differences among students of various racial and ethnic groups in course-taking in such areas as math, science, and foreign language, for students with similar course-taking records, achievement test score differences by race or ethnicity narrow substantially.

Robert Dreeben and colleagues at the University of Chicago conducted a long line of studies documenting both the relationship between educational opportunities and student performance and minority students’ access to those opportunities. In a comparative study of 300 Chicago first graders, for example, Dreeben found that African-American and white students who had comparable instruction achieved comparable levels of reading skill. But he also found that the quality of instruction given African-American students was, on average, much lower than that given white students, thus creating a racial gap in aggregate achievement at the end of first grade. In fact, the highest-ability group in Dreeben’s sample was in a school in a low-income African-American neighborhood. These children, though, learned less during first grade than their white counterparts because their teacher was unable to provide the challenging instruction they deserved.

When schools have radically different teaching forces, the effects can be profound. For example, when Eleanor Armour-Thomas and colleagues compared a group of exceptionally effective elementary schools with a group of low-achieving schools with similar demographic characteristics in New York City, roughly 90 percent of the variance in student reading and mathematics scores at grades 3, 6, and 8 was a function of differences in teacher qualifications. The schools with highly qualified teachers serving large numbers of minority and low-income students performed as well as much more advantaged schools.

Most studies have estimated effects statistically. However, an experiment that randomly assigned seventh grade “at-risk”students to remedial, average, and honors mathematics classes found that the at-risk students who took the honors class offering a pre-algebra curriculum ultimately outperformed all other students of similar backgrounds. Another study compared African-American high school youth randomly placed in public housing in the Chicago suburbs with city-placed peers of equivalent income and initial academic attainment and found that the suburban students, who attended largely white and better-funded schools, were substantially more likely to take challenging courses, perform well academically, graduate on time, attend college, and find good jobs.

What Can Be Done?

This state of affairs is not inevitable. Last year the National Commission on Teaching and America’s Future issued a blueprint for a comprehensive set of policies to ensure a “caring, competent, and qualified teacher for every child,” as well as schools organized to support student success. Twelve states are now working directly with the commission on this agenda, and others are set to join this year. Several pending bills to overhaul the federal Higher Education Act would ensure that highly qualified teachers are recruited and prepared for students in all schools. Federal policymakers can develop incentives, as they have in medicine, to guarantee well-prepared teachers in shortage fields and high-need locations. States can equalize education spending, enforce higher teaching standards, and reduce teacher shortages, as Connecticut, Kentucky, Minnesota, and North Carolina have already done. School districts can reallocate resources from administrative superstructures and special add-on programs to support better-educated teachers who offer a challenging curriculum in smaller schools and classes, as restructured schools as far apart as New York and San Diego have done. These schools, in communities where children are normally written off to lives of poverty, welfare dependency, or incarceration, already produce much higher levels of achievement for students of color, sending more than 90 percent of their students to college. Focusing on what matters most can make a real difference in what children have the opportunity to learn. This, in turn, makes a difference in what communities can accomplish.

An Entitlement to Good Teaching

The common presumption about educational inequality—that it resides primarily in those students who come to school with inadequate capacities to benefit from what the school has to offer—continues to hold wide currency because the extent of inequality in opportunities to learn is largely unknown. We do not currently operate schools on the presumption that students might be entitled to decent teaching and schooling as a matter of course. In fact, some state and local defendants have countered school finance and desegregation cases with assertions that such remedies are not required unless it can be proven that they will produce equal outcomes. Such arguments against equalizing opportunities to learn have made good on DuBois’s prediction that the problem of the 20th century would be the problem of the color line.

But education resources do make a difference, particularly when funds are used to purchase well-qualified teachers and high-quality curriculum and to create personalized learning communities in which children are well known. In all of the current sturm und drang about affirmative action, “special treatment,” and the other high-volatility buzzwords for race and class politics in this nation, I would offer a simple starting point for the next century s efforts: no special programs, just equal educational opportunity.

Governance Studies

Annelies Goger, Katherine Caves, Hollis Salway

May 16, 2024

Sofoklis Goulas, Isabelle Pula

Melissa Kay Diliberti, Elizabeth D. Steiner, Ashley Woo

Race, ethnicity and education : Background information

- Background information

- Next: Recent e-books >>

- Recent e-books

- Recent print books

- Connect to Stanford e-resources

- Last Updated: May 24, 2024 12:41 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.stanford.edu/race_and_ed

Recommended pages

- Undergraduate open days

- Postgraduate open days

- Accommodation

- Information for teachers

- Maps and directions

- Sport and fitness

Race Ethnicity and Education

Supported by the AERA Critical Examination of Race, Ethnicity, Class and Gender in Education Special Interest Group and the BERA ’Race’ Ethnicity and Education Special Interest Group.

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Still Separate, Still Unequal: Teaching about School Segregation and Educational Inequality

By Keith Meatto

- May 2, 2019

Racial segregation in public education has been illegal for 65 years in the United States. Yet American public schools remain largely separate and unequal — with profound consequences for students, especially students of color.

Today’s teachers and students should know that the Supreme Court declared racial segregation in schools to be unconstitutional in the landmark 1954 ruling Brown v. Board of Education . Perhaps less well known is the extent to which American schools are still segregated. According to a recent Times article , “More than half of the nation’s schoolchildren are in racially concentrated districts, where over 75 percent of students are either white or nonwhite.” In addition, school districts are often segregated by income. The nexus of racial and economic segregation has intensified educational gaps between rich and poor students, and between white students and students of color.

Although many students learn about the historical struggles to desegregate schools in the civil rights era, segregation as a current reality is largely absent from the curriculum.

“No one is really talking about school segregation anymore,” Elise C. Boddie and Dennis D. Parker wrote in this 2018 Op-Ed essay. “That’s a shame because an abundance of research shows that integration is still one of the most effective tools that we have for achieving racial equity.”

The teaching activities below, written directly to students, use recent Times articles as a way to grapple with segregation and educational inequality in the present. This resource considers three essential questions:

• How and why are schools still segregated in 2019? • What repercussions do segregated schools have for students and society? • What are potential remedies to address school segregation?

School segregation and educational inequity may be a sensitive and uncomfortable topic for students and teachers, regardless of their race, ethnicity or economic status. Nevertheless, the topics below offer entry points to an essential conversation, one that affects every American student and raises questions about core American ideals of equality and fairness.

Six Activities for Students to Investigate School Segregation and Educational Inequality

Activity #1: Warm-Up: Visualize segregation and inequality in education.

Based on civil rights data released by the United States Department of Education, the nonprofit news organization ProPublica has built an interactive database to examine racial disparities in educational opportunities and school discipline. In this activity, which might begin a deeper study of school segregation, you can look up your own school district, or individual public or charter school, to see how it compares with its counterparts.

To get started: Scroll down to the interactive map of the United States in this ProPublica database and then answer the following questions:

1. Click the tabs “Opportunity,” “Discipline,” “Segregation” and “Achievement Gap” and answer these two simple questions: What do you notice? What do you wonder? (These are the same questions we ask as part of our “ What’s Going On in This Graph? ” weekly discussions.) 2. Next, click the tabs “Black” and “Hispanic.” What do you notice? What do you wonder? 3. Search for your school or district in the database. What do you notice in the results? What questions do you have?

For Further Exploration

Research your own school district. Then write an essay, create an oral presentation or make an annotated map on segregation and educational inequity in your community, using data from the Miseducation database.

Activity #2: Explore a case study: schools in Charlottesville, Va.

The New York Times and ProPublica investigated how segregation still plays a role in shaping students’ educational experiences in the small Virginia city of Charlottesville. The article begins:

Zyahna Bryant and Trinity Hughes, high school seniors, have been friends since they were 6, raised by blue-collar families in this affluent college town. They played on the same T-ball and softball teams, and were in the same church group. But like many African-American children in Charlottesville, Trinity lived on the south side of town and went to a predominantly black neighborhood elementary school. Zyahna lived across the train tracks, on the north side, and was zoned to a mostly white school, near the University of Virginia campus, that boasts the city’s highest reading scores.

Before you read the rest of the article, and learn about the experiences of Zyahna and Trinity, answer the following questions based on your own knowledge, experience and opinions:

• What is the purpose of public education? • Do all children in America receive the same quality of education? • Is receiving a quality public education a right (for everyone) or a privilege (for some)? • Is there a correlation between students’ race and the quality of education they receive?

Now read the entire article about lingering segregation in Charlottesville and answer the following questions:

1. How is Charlottesville’s school district geographically and racially segregated? 2. How is Charlottesville a microcosm of education in America? 3. How do white and black students in Charlottesville compare in terms of participation in gifted and talented programs; being held back a grade; being suspended from school? 4. How do black and white students in Charlottesville compare in terms of reading at grade level? 5. How do Charlottesville school officials explain the disparities between white and black students? 6. Why are achievement disparities so common in college towns? 7. In what ways do socioeconomics not fully explain the gap between white and black students?

After reading the article and answering the above questions, share your reactions using the following prompts:

• Did anything in the article surprise you? Shock you? Make you angry or sad? Why? • On the other hand, did anything in the article strike you as unsurprising? Explain. • How might education in Charlottesville be made more equitable?

Choose one or more of the following ideas to investigate school segregation in the United States and around the world.

1. Read and discuss “ In a Divided Bosnia, Segregated Schools Persist .” Compare and contrast the situations in Bosnia and Charlottesville. How does this perspective confirm, challenge, or complicate your understanding of the topic?

2. Read and discuss the article and study the map and graphs in “ Why Are New York’s Schools Segregated? It’s Not as Simple as Housing .” How does “school choice” confirm, challenge or complicate your understanding of segregation and educational inequity?

3. Only a tiny number of black students were offered admission to the highly selective public high schools in New York City in 2019, raising the pressure on officials to confront the decades-old challenge of integrating New York’s elite public schools. To learn more about this story, listen to this episode of The Daily . For more information, read these Op-Ed essays and editorials offering different perspectives on the problem and possible solutions. Then, make a case for what should be done — or not done — to make New York’s elite public schools more diverse.

• Stop Fixating on One Elite High School, Stuyvesant. There Are Bigger Problems. • How Elite Schools Stay So White • No Ethnic Group Owns Stuyvesant. All New Yorkers Do. • De Blasio’s Plan for NYC Schools Isn’t Anti-Asian. It’s Anti-Racist. • New York’s Best Schools Need to Do Better

3. Read and discuss “ The Resegregation of Jefferson County .” How does this story confirm, challenge or complicate your understanding of the topic?

Activity #3: Investigate the relationship between school segregation, funding and inequality.

Some school districts have more money to spend on education than others. Does this funding inequality have anything to do with lingering segregation in public schools? A recent report says yes. A New York Times article published in February begins:

School districts that predominantly serve students of color received $23 billion less in funding than mostly white school districts in the United States in 2016, despite serving the same number of students, a new report found. The report, released this week by the nonprofit EdBuild, put a dollar amount on the problem of school segregation, which has persisted long after Brown v. Board of Education and was targeted in recent lawsuits in states from New Jersey to Minnesota. The estimate also came as teachers across the country have protested and gone on strike to demand more funding for public schools.

Answer the following questions based on your own knowledge, experience and opinions.

• Who pays for public schools? • Is there a correlation between money and education? Does the amount of money a school spends on students influence the quality of the education students receive?

Now read the rest of the Times article about funding differences between mostly white school districts and mostly nonwhite ones, and then answer the following questions:

1. How much less total funding do school districts that serve predominantly students of color receive compared to school districts that serve predominantly white students? 2. Why are school district borders problematic? 3. How many of the nation’s schoolchildren are in “racially concentrated districts, where over 75 percent of students are either white or nonwhite”? 4. How much less money, on average, do nonwhite districts receive than white districts? 5. How are school districts funded? 6. How does lack of school funding affect classrooms? 7. What is the new kind of ”white flight” in Arizona and why is it a problem? 8. What is an “enclave”? What does the statement “some school districts have become their own enclaves” mean?

• Did anything in the article surprise you? Shock you? Make you angry or sad? Why? • On the other hand, did anything in the article strike you as unsurprising? Explain. • How could school funding be made more equitable?

Choose one or more of the following ideas to investigate the interrelationship among school segregation, funding and inequality.

1. Research your local school district budget, using public records or local media, such as newspapers or television reporting. What is the budget per student? How does that budget compare with the state average? The national average? 2. Compare your findings about your local school budget to your research about segregation and student outcomes, using the Miseducation database. Do the results of your research suggest any correlations?

Activity #4: Examine potential legal remedies to school segregation and educational inequality.

How do we get better schools for all children? One way might be to take the state to court. A Times article from August reports on a wave of lawsuits that argue that states are violating their constitutions by denying children a quality education. The article begins:

By his own account, Alejandro Cruz-Guzman’s five children have received a good education at public schools in St. Paul. His two oldest daughters are starting careers in finance and teaching. Another daughter, a high-school student, plans to become a doctor. But their success, Mr. Cruz-Guzman said, flows partly from the fact that he and his wife fought for their children to attend racially integrated schools outside their neighborhood. Their two youngest children take a bus 30 minutes each way to Murray Middle School, where the student population is about one-third white, one-third black, 16 percent Asian and 9 percent Latino. “I wanted to have my kids exposed to different cultures and learn from different people,” said Mr. Cruz-Guzman, who owns a small flooring company and is an immigrant from Mexico. When his two oldest children briefly attended a charter school that was close to 100 percent Latino, he said he had realized, “We are limiting our kids to one community.” Now Mr. Cruz-Guzman is the lead plaintiff in a lawsuit saying that Minnesota knowingly allowed towns and cities to set policies and zoning boundaries that led to segregated schools, lowering test scores and graduation rates for low-income and nonwhite children.

Read the entire article and then answer the following questions:

1. What does Mr. Cruz-Guzman’s suit allege against the State of Minnesota? 2. Why are advocates for school funding equity focused on state government, as opposed to the federal government? 3. What did a state judge rule in New Mexico? What did the Kansas Supreme Court rule? 4. What fraction of fourth and eighth graders in New Mexico is not proficient in reading? What does research suggest may improve their test scores? 5. According to a 2016 study, if a school spends 10 percent more per pupil, what percentage more would students earn as adults? 6. What does the economist Eric Hanushek argue about the correlation between spending and student achievement? 7. What remedy for school segregation is Daniel Shulman, the lead lawyer in the Minnesota desegregation suit, considering? Why are charter schools nervous about the case? 8. How does Khulia Pringle see some charter schools as “culturally affirming”? What problems does Ms. Pringle see with busing white children to black schools and vice versa?

• Did anything in the article surprise you? What other emotional responses did you have while reading? Why? • On the other hand, did anything in the article strike you as unsurprising? Explain. • Do the potential “cultural” benefits of school segregation outweigh the costs?

Choose one or more of the following ideas to investigate potential remedies to school segregation and educational inequality.

1. Read the obituaries “ Jean Fairfax, Unsung but Undeterred in Integrating Schools, Dies at 98 ” and “ Linda Brown, Symbol of Landmark Desegregation Case, Dies at 75 .” How do their lives inform your grasp of legal challenges to segregation?

2. Watch the following video about school busing . How does this history inform your understanding of the benefits and challenges of busing?

3. Read about how parents in two New York City school districts are trying to tackle segregation in local middle schools . Then decide if these models have potential for other districts in New York or around the country. Why or why not?

Activity #5: Consider alternatives to integration.

Is integration the best and only choice for families who feel their children are being denied a quality education? A recent Times article reports on how some black families in New York City are choosing an alternative to integration. The article begins:

“I love myself!” the group of mostly black children shouted in unison. “I love my hair, I love my skin!” When it was time to settle down, their teacher raised her fist in a black power salute. The students did the same, and the room hushed. As children filed out of the cramped school auditorium on their way to class, they walked by posters of Colin Kaepernick and Harriet Tubman. It was a typical morning at Ember Charter School in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn, an Afrocentric school that sits in a squat building on a quiet block in a neighborhood long known as a center of black political power. Though New York City has tried to desegregate its schools in fits and starts since the 1954 Supreme Court ruling in Brown v. Board of Education, the school system is now one of the most segregated in the nation. But rather than pushing for integration, some black parents in Bedford-Stuyvesant are choosing an alternative: schools explicitly designed for black children.

Before you read the rest of the article, answer the following questions based on your own knowledge, experience and opinions:

• Should voluntary segregation in schools be permissible? Why or why not? • What potential benefits might voluntary segregation offer? • What potential problems might it pose?

Now, read the entire article and then answer these questions:

1. What is the goal of Afrocentric schools? 2. Why are some parents and educators enthusiastic about Afrocentric schools? 3. Why are some experts wary of Afrocentric schools? 4. What does Alisa Nutakor want to offer minority students at Ember? 5. What position does the city’s schools chancellor take on Afrocentric schools? 6. What “modest desegregation plans” have some districts offered? With what result? 7. Why did Fela Barclift found Little Sun People? 8. Why are some parents ambivalent about school integration? According to them, how can schools be more responsive to students of color? 9. What does Mutale Nkonde mean by the phrase “not all boats are rising”? 10. What did Jordan Pierre gain from his experience at Eagle Academy?

• Did anything in the article surprise you? What other emotional responses did you have while reading? Why? • On the other hand, did anything in the article strike you as unsurprising? Explain. • Did the article challenge your opinion about voluntary segregation? How?

Choose one or more of the following ideas to investigate some of the complicating factors that influence where parents decide to send their children to school.

1. Read and discuss “ Choosing a School for My Daughter in a Segregated City .” How does reading about segregation, inequity and school choice from a parent’s perspective confirm, challenge or complicate your understanding of the topic?

2. Read “ Do Students Get a Subpar Education in Yeshivas? ” How might a student’s religious affiliation complicate the issue of segregation and inequity in education?

Activity #6: Learn more and take action.

Segregation still persists in public schools more than 60 years after the Brown v. Board of Education decision. What more can you learn about the issue? What choices can you make? Is there anything students can do about the issue?

Write a personal essay about your experience with school segregation. For inspiration, read Erin Aubrey Kaplan’s op-ed essay, “ School Choice Is the Enemy of Justice ,” which links a contemporary debate with the author’s personal experience of school segregation.

Interview a parent, grandparent or another adult about their educational experiences related to segregation, integration and inequity in education. Compare their experiences with your own. Share your findings in a paper, presentation or class discussion.

Take action by writing a letter about segregation and educational inequity in your community. Send the letter to a person or organization with local influence, such as the school board, an elected official or your local newspaper.

Discuss the issue in your school or district by raising the topic with your student council, parent association or school board. Be prepared with information you discovered in your research and bring relevant questions.

Additional Resources

Choices in Little Rock | Facing History and Ourselves

Beyond Brown: Pursuing the Promise | PBS

Why Are American Public Schools Still So Segregated? | KQED

Toolkit for “Segregation by Design” | Teaching Tolerance

- < Previous

Home > Fordham University Press > Electronic Books > Education > 6

Discussion Questions for Teaching While Black

Pamela Lewis

Buy this book.

- Disciplines

Education | Educational Sociology | Race and Ethnicity | Urban Education | Urban Studies and Planning

These discussion questions accompany Teaching While Black: A New Voice on Race and Education in New York City .

Recommended Citation

Lewis, Pamela, "Discussion Questions for Teaching While Black" (2020). Education . 6. https://research.library.fordham.edu/education/6

Since July 22, 2020

Included in

Educational Sociology Commons , Race and Ethnicity Commons , Urban Education Commons , Urban Studies and Planning Commons

To view the content in your browser, please download Adobe Reader or, alternately, you may Download the file to your hard drive.

NOTE: The latest versions of Adobe Reader do not support viewing PDF files within Firefox on Mac OS and if you are using a modern (Intel) Mac, there is no official plugin for viewing PDF files within the browser window.

Advanced Search

- Notify me via email or RSS

- Collections

Author Corner

Home | About | FAQ | My Account | Accessibility Statement

Privacy Copyright

Classroom Q&A

With larry ferlazzo.

In this EdWeek blog, an experiment in knowledge-gathering, Ferlazzo will address readers’ questions on classroom management, ELL instruction, lesson planning, and other issues facing teachers. Send your questions to [email protected]. Read more from this blog.

Equity? Equality? How Educators Can Tell the Difference

- Share article

Today’s post is the latest in a series on the difference between equity and equality .

‘Every Student Doesn’t Need the Same Thing’

Karen Baptiste, Ed.D., a senior consultant at McREL International, is a former special education teacher, instructional coach, and director who now works with K–12 schools across the United States to support improved teaching and learning. She is a co-author of The New Classroom Instruction That Works :

It’s common for educators to believe and teach that everyone should be treated fairly and equally. Having been a special education teacher, and being a person of color, I understand the impact on a child’s life when we treat everyone equally.

Equality, in general terms, is the belief that everyone should get the same treatment, the same resources, and the same starting point. That would be OK if our society did not rank race, gender, (dis)ability, religion, etc. Unfortunately, people of color have dealt with racism and oppression for hundreds of years, and they have not had equal treatment, fairness, nor the same starting point. When teachers say they want equality, what they are saying is that they want all of their students to be treated the same and, therefore, do not see or acknowledge the differences among their students.

When an educator says they believe in equality over equity, they overlook their students’ unique characteristics, abilities, and traits that make them who they are and alleviate themselves from the responsibility of having to address their students’ needs. Most people want to avoid discomfort, especially when the topic of race is surfaced. There is fear of getting it wrong or being accused of being a racist, so it’s easier to say “I treat all of my students the same.”

Equity acknowledges and addresses the unique needs of each student, and it is what we need to work toward. Because of my dark skin, and because of my gender, and because of the texture of my hair, and because of the language I speak, I am born into a world where I am too often dismissed and seen as inferior, not just in school but at work, when buying a home, shopping at the grocery store, traveling, and engaging in any part of living life. There is no part of our lives that has gone untouched by racism and/or discrimination. People of color are still fighting today to be seen and heard as an equal, valued member in the world. Until that happens, we can’t talk about equality.

Equity says I see you.

Equity says I want to understand you.

Equity says I accept your Black and brown skin.

Equity says there is nothing wrong with you or your existence in the world.

Equity says I recognize your learning needs and I am willing to learn the best ways to teach you and provide you with the resources that you need to be successful so that you can feel equal in this space.

Every student doesn’t need the same thing. Equality pushes for everyone to get the same thing, while equity is about giving every student what they need to be successful. Let’s set aside the topic of race momentarily and think about the grave outcomes if we treat students with special needs equal to their peers without special needs. What if the expectation during physical education class is to run two laps in a specified time? Students who use a wheelchair cannot realistically meet that expectation. This is why the federal law requires children designated for special education services to have an individualized education program, because their needs are not equal; they do not need equal treatment, they need equitable treatment and resources in order to access a quality education. Now, think about your student in class who needs to use manipulatives during a math lesson while other students can do mental math.

All students learn differently and can meet mastery when equity becomes part of your practice. Some might consider this pedantic when discussing equality and equity, but it’s not. Providing students with the resources they need to be successful provides them with the psychological safety that is sometimes missing in classrooms but gravely needed.

‘Equity Is Not an Initiative’

PJ Caposey is the Illinois Superintendent of the Year and is a best-selling author, having written nine books for various publishers. PJ is a sought after presenter and consultant who has a widely read weekly newsletter available at www.pjcaposey.com :

Sometimes, I think the concept of equity compared to equality is very difficult and complex. Other times, I think it is straightforward and people out of an act of willful ignorance choose not to understand. I work hard to keep a positive mindset, so my intent in this is to provide six practical examples to demonstrate the difference and how it plays out in schools.

- A student’s grandmother is in the hospital, and their attendance suffers, so you modify some assignments to ensure you are measuring their progress toward standards but limiting the volume to best meet the student’s needs. EQUITY

- A student’s grandmother is in the hospital, and their attendance suffers, and you keep them responsible for the exact work everyone else must complete. EQUALITY

- A student struggles to read and has a documented disability, so their tests are read to them. EQUITY

- A student struggles to read and has a documented disability, but you provide zero assistance to them because it would not be fair to the other students. EQUALITY

- A district analyzes their data and creates plans to close achievement gaps by paying special attention to those groups not performing well. EQUITY

- A district analyzes their data and creates improvement plans that are equally applied to all students. EQUALITY

- Based on benchmark assessment results, some students are placed in intervention groupings to support their learning needs. EQUITY

- Despite assessment results, all students receive the exact same instruction throughout the course of the day. EQUALITY

- All students who wish to participate in Advanced Placement courses are allowed to do so despite previous performance if they attend an in-person meeting articulating the demands of the course. EQUITY

- Only students who have a 3.2 grade point average and have had less than five missing assignments per year on average are allowed to participate in Advanced Placement courses without any exceptions. EQUALITY

- Some staff members have advanced degrees in reading so their professional development requirements around the new reading curriculum are altered to acknowledge their expertise. EQUITY

- All staff members are required to attend the same professional development regardless of prior knowledge or expertise. EQUALITY

My point in sharing these very realistic examples of equity versus equality is twofold. I have come to the realization that we “DO” equity far more than some people would elect to realize. Second, even those who are reluctant to embrace the fact that schools should have an equity focus typically want schools to make equitable decisions when it comes to them or their children. From that statement, feel free to extrapolate what you will.

I will leave with one last thought on the topic. Equity is not a goal. Equity is not an initiative. Equity is a mindset and a lens through which we make innumerable decisions every single day. Whenever we consider how we can best serve an individual student or lead an individual staff member by meeting them where they are at and helping them to get where they need to be, we are operating with an equity mindset.

‘Equity Empowers’

A retired teacher and speaker, Denise Fawcett Facey now writes on education issues. Among her books, Can I Be in Your Class focuses on ways to enliven classroom learning:

The words “That’s not fair” have become a virtual children’s anthem. Heard from homes to playgrounds to classrooms, those three words—spoken almost in the cadence of a song—are the outcry of kids everywhere, conveying their frustration over what they perceive as unequal treatment when things don’t go as they expected. Although we tend to ignore that all-too-common outburst, the early sense of justice that underlies it just as often informs adult concepts of equality as well, fostering an expectation that everyone will be treated the same. However, there is a striking difference between appearing to treat everyone equally and ensuring that everyone has the equity offered by an equal opportunity.

In an educational setting, affording everyone an equal chance at success means equity supersedes equality. From differentiation in teaching methods to the hiring of teachers, among other factors, here are four differences between equality and equity:

- Differentiation. Just as we don’t expect all students to wear eyeglasses in the name of equality, we shouldn’t expect all students to learn in the same way, either. Differentiation settles that. Providing what each student needs for optimal learning, it might be as simple as eyeglasses, preferential seating, or extended time for assignments. However, the chance to present mastery in multiple ways or to use books and other resources that are culturally relevant are also means of differentiation. Although the content area is the same for all students, as are the myriad tools available (there’s your equality), each uses the tool that enables that student to achieve success. That’s not only differentiation. It’s equity.

- Admission to gifted classes. While white, able-bodied students of a certain intellectual ability and socioeconomic level generally have an equal opportunity to be admitted to classes for gifted students, admission tends to exclude students of color as well as students with physical disabilities and those of lower socioeconomic levels, all of whom have eligible students among them. Equality makes certain that all schools have classes for gifted students. Equity goes beyond that, seeking to identify gifted students among those underrepresented groups within each school and assuring that they also gain admittance to gifted classes once identified.

- Hiring diverse teachers. It’s easy to point with pride to teachers of color in a district or to teachers who use wheelchairs, believing them to be reflections of equality and diversity. However, how many are there? And where are these teachers placed? Equality merely says there are some of each. Equity provides an equal opportunity for ALL teachers to teach at any school, not simply affording them an interview at the “better” schools with no hope of being hired nor relegating these teachers to schools designated “inner city” or “low achieving.” Equity also ensures that the number of teachers outside the dominant group is at least representative of their numbers in that community.

- A seat at the table. Much like hiring practices, opening a committee or group to people not normally invited is ostensibly equality. After all, this type of equality frequently involves having “one of each kind,” so to speak, with representation from various racial and ethnic groups and possibly from different ability groups as well. However, it’s certainly not equity as the newly invited are expected to be grateful for the invitation, not to be bold enough to participate as equals. Without affording these participants a genuine voice, it’s educational tokenism that solely allows one to be present. Equity, on the other hand, balances power, legitimizing each person’s voice.

Returning to that childhood question of fairness, equity is the true answer for both students and educators. Offering an equal playing field for success, equity empowers, placing everyone on equal footing.

Thanks to Karen, PJ, and Denise for contributing their thoughts!

Today’s post answered this question:

It’s not unusual for districts, schools, and educators to confuse “equality” with “equity.” What are examples, and ways, you would help them understand the difference?

Part One in this series featured responses from Jehan Hakim, Mary Rice-Boothe, Jennifer Cárdenas, and Shaun Nelms.

Consider contributing a question to be answered in a future post. You can send one to me at [email protected] . When you send it in, let me know if I can use your real name if it’s selected or if you’d prefer remaining anonymous and have a pseudonym in mind.

You can also contact me on Twitter at @Larryferlazzo .

Just a reminder; you can subscribe and receive updates from this blog via email . And if you missed any of the highlights from the first 12 years of this blog, you can see a categorized list here .

The opinions expressed in Classroom Q&A With Larry Ferlazzo are strictly those of the author(s) and do not reflect the opinions or endorsement of Editorial Projects in Education, or any of its publications.

Sign Up for The Savvy Principal

Edweek top school jobs.

Sign Up & Sign In

- Publications

Toggle navigation

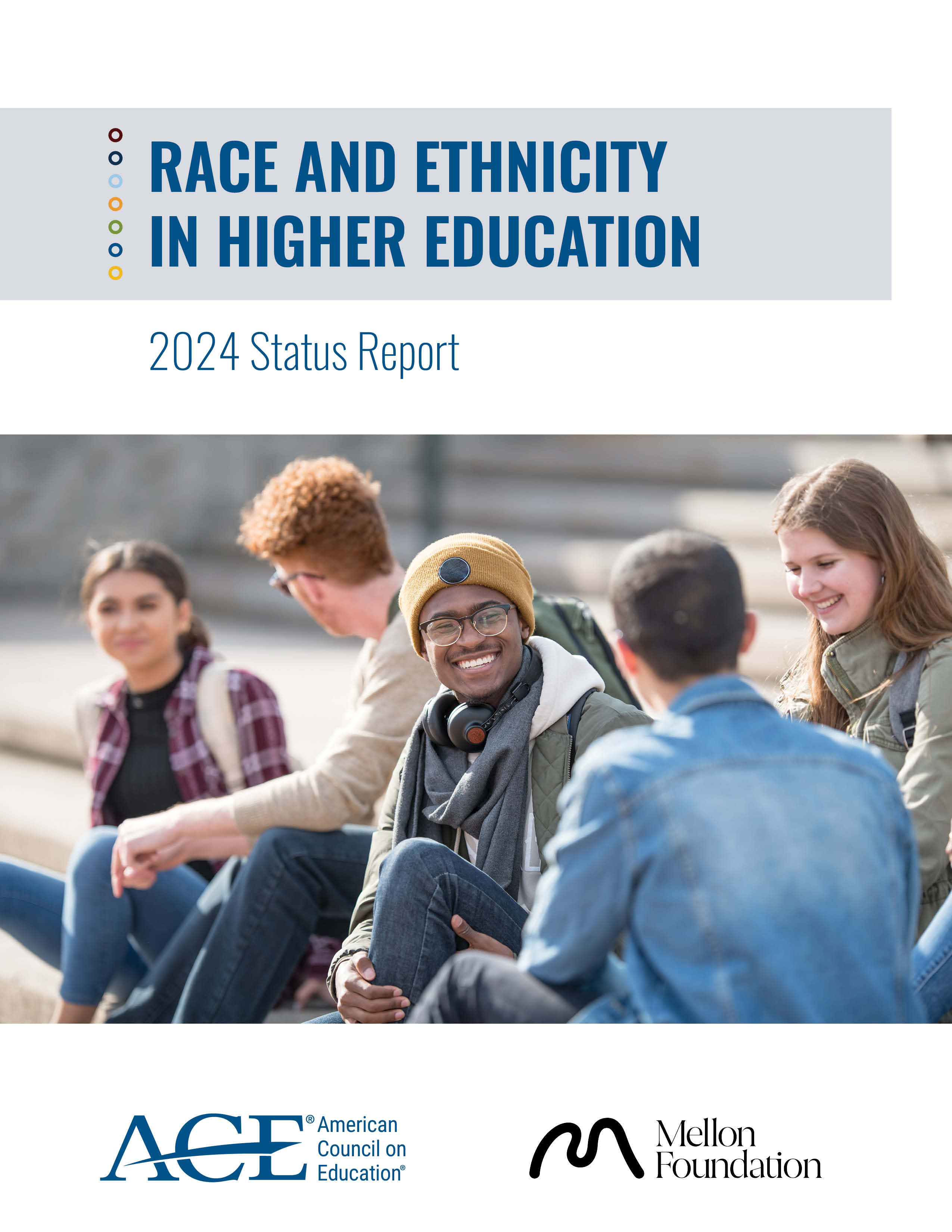

ACE Releases 2024 Update to Race and Ethnicity in Higher Education Project May 21, 2024

As the diversity of the U.S. population increased, more Hispanic and Latino, Black and African American students have enrolled in undergraduate programs over the last 20 years, according to data outlined in the report. However, completion rates have not risen accordingly—the number of Hispanic or Latino students earning bachelor’s degrees rose about 10 percent from 2002 to 2022, while the rates for white and Asian students grew even faster, widening the existing gaps.

Black or African American students consistently had lower completion rates than those of any other racial and ethnic group. Black or African American, Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, Hispanic or Latino, and American Indian or Alaska Native students earned a larger share of associate degrees and certificates, while bachelor’s degrees are mainly earned by Asian, White, and multiracial students.

“Despite some progress, racial disparities are still alarmingly high, especially in light of the Supreme Court’s decision to end race-conscious admissions,” stated Ted Mitchell, the president of ACE. “This report is timely for everyone involved in higher education—administrators, researchers, policymakers. It allows us to examine the current state of race and ethnicity in higher education and strive to bridge these equity gaps.”

The data also reveal disparities in how students pay for college, with Black or African American undergraduate students borrowing at the highest rates across all sectors and income groups (49.7 percent). Hispanic or Latino and Asian students borrowed at lower-than-average rates. However, Asian students borrowed the highest amount per borrower when including parent loans.

Additionally, the report provides a look at the diversity of faculty and staff across race and ethnicity. In 2021, 69.4 percent of all full-time faculty and 56.2 percent of newly hired full-time faculty were White, compared to Black or African American full-time faculty (6.1 percent) and new full-time faculty (9.3 percent).

“This report is just one of the ways ACE is working to democratize data by creating accessible and actionable insights that empower evidence-inspired decision-making across the postsecondary landscape,” said Hironao Okahana, assistant vice president and executive director of ACE’s Education Futures Lab. “This work bolsters our engagement in the data ecosystem, such as our partnership with the UCLA School of Education and Information Studies, to strengthen and lead the Higher Education Research Institute (HERI ) and the recently announced Global Data Consortium Initiative.”

This status report builds on the findings from preceding publications in the Race and Ethnicity in Higher Education series. It presents 201 indicators drawn from eight data sources, most of which come from the U.S. Department of Education and U.S. Census Bureau. The indicators present a snapshot of the most recent publicly available data, while others depict data over time.

The Race and Ethnicity in Higher Education: 2024 Status Report was made possible through the generous support of the Mellon Foundation. The accompanying website was generously supported by the Mellon Foundation and the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation.

Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World