An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Funct Morphol Kinesiol

Why Would You Choose to Do an Extreme Sport?

Giuseppe musumeci.

1 Department of Biomedical and Biotechnological Sciences, Human, Histology and Movement Science Section, University of Catania, Via S. Sofia n°87, 95123 Catania, Italy; ti.tcinu@ireguamaizarg or [email protected] ; Tel.: +39-095-378-2043

2 Research Center on Motor Activities (CRAM), University of Catania, Via S. Sofia n°97, 95123 Catania, Italy

3 Department of Biology, Sbarro Institute for Cancer Research and Molecular Medicine, College of Science and Technology, Temple University, Philadelphia, PA 19122, USA

Why do so many athletes keep practicing extreme sports, even though they know the danger of risking their lives? Why is our body addicted to these strong emotions? I will try to address these questions in this short editorial.

The thrills given by extreme sports attract many individuals seeking excitement. Many of these extreme sports like snowboarding, surfing, skateboarding, rock climbing, bungee jumping, skydiving, and others, allow one to feel the freedom to challenge yourself, both physically and psychologically, and to perform any type of freestyling that would be nauseating to athletes. However, almost all extreme sports have some elements that could endanger an athlete’s life in comparison to traditional sports. These sports could be defined as “extreme” due to their tendency to be dangerous if not performed carefully or with the right equipment [ 1 ]. After all, to experience the true “adrenaline kick,” these sports must be dangerous. Serious injuries are common among adrenaline junkies and many fatalities are reported every year. To give an example of this phenomenon according to the report of the United States Parachute Association, more than twenty people a year die due to parachuting alone. The effort required by these sports is great, but the supply of adrenaline and other hormones is sufficient to avoid tiredness resulting from exercise. The adrenaline rush increases the acceleration of blood flows to the muscles and brain, relaxes the muscles, and lastly helps with the conversion of glycogen into glucose in the liver. For every extreme sports athlete, this adrenaline rush is never enough since they are always seeking stronger emotions.

This kind of feeling cannot be otherwise experienced and many of these extreme sports athletes do not even consider a life without the excitement of these powerful moments. Furthermore, extreme sports have the capacity to establish a strong bond between individuals, thanks to the dangerous elements of the activity that requires a high level of trust between people. Consequently, this kind of friendship bond has a good impact on mental health [ 2 ].

The typical challenges and performances of the so-called “extreme sports” draw the attention of the spectators, growing the interest of researchers in this kind of behavior. The reasons why risk-lovers are attracted to challenges in dangerous places, or to the possibility of facing the unknown or even to the extreme conditions in which it must be lived, are strictly related to their interpretation of life, to their need of challenging life and to have complete control of the most uncertain situations [ 3 ].

These aspects need to be monitored and reworked in case of predominance of self-destructive tendencies, or when evaluating self-capacities. In this situation, the tendency to underestimate the risk could hide the overestimation of the self, or a devaluation of life caused by a non-depressive mental state that can lead to a latently desired death [ 1 ]. However, most extreme sports enthusiasts are not driven by self-destructive tendencies. One of the most important aspects of extreme sports that fascinates people is the possibility to live experiences that make you feel alive in a way out of the ordinary, that generate euphory described with expressions like “feeling in the eye of the storm” or “look I’m getting” or “feel the adrenaline rush”.

Some studies tried to explain the neuropsychological reasons that may lead some people more than others to look for “no limits” experiences. These studies found a correlation between the ability of certain activities to enhance adrenaline’s secretion, the need to take risks, and the inclination to seek extreme experiences. This chemical response is closely related to the so-called “fight or flight”, which is able to generate chills reported as “pleasant” in those who frequently seek these kinds of experience. The feeling of imminent danger elicited by these extreme sports activates the survival mechanisms in response to stress in order to face the event through neurophysiological changes broadly acknowledged by the literature [ 2 ].

However, it is possible to activate the “fight or flight” response in the average population even with activities that guarantee great safety and that allow people to deal with uncertainties or changes with respect to the usual point of reference: like the small challenges to daily habits of some game at the funfair that are able to elicit a pleasant, and safe, euphory. Emotional experiences on daily life have also been related to the release of neuromediators, which is physiologically activated in several situations faced by the individuals.

In these scenarios, the organism produces a large amount of dopamine which is known to elicit the sensation of pleasure similar to those experienced with alcohol, drugs, or sexual intercourse. Therefore, this explains (along with the presence of adrenaline) the frequent propensity to uncontrollably smile or scream while living those experiences. The common attraction towards these situations has also been studied in relation to a gene mutation that could cause a lower presence of dopamine receptors. This mutation has been found in many people who express attraction to extreme sports; therefore, it was considered among the possible physiological reasons that can explain the tendency to experiment with extreme activities, since the latter would be able to induce the overproduction of dopamine in order to obtain those physiological effects which are physiologically achieved at a lower level of stimulation in people with, otherwise, a greater number of dopaminergic receptors [ 4 ].

Many other studies on the typical personality of extreme sports enthusiasts spotted in these people the propensity to seek strong emotions, and this has led to the definition of “sensation seekers”, a psychological aspect very common between paratroopers, free climbers, and other athletes practicing extreme sports or showing addiction to exercise [ 5 ]. In a similar context, it is possible to place the psychological studies that have compared the differences between common people and “sensation seekers”. Sensation seekers are characterized by a need to try the extreme, in search of thrills, even though it implies doing dangerous sports.

These kinds of people avoid trivial experiences because they need high-emotional situations (like drug addicts), developing a sort of “shivering tolerance”, forcing them to seek higher doses of emotion every time to reach the same sensation as before. When this occurs, they get used to the same extreme challenge and start looking for a more intense one, to feel the thrill again, risking death just as might happen in drug addiction. In these situations, the need to seek the thrill is combined with a system of values or criminal behaviour tendencies, fuelled by an altered evaluation of life: the result is the pursuit of one’s passion, putting in danger himself and other lives [ 2 ].

There are various reasons why it would be interesting to tackle the challenge of extreme sports, but before venturing into them, it is necessary to consider and reflect on the above-discussed arguments. Furthermore, people who want to undertake these sports should be careful about their own and others’ physical integrity, because sport should simply improve the psychophysical abilities of the person and not the other way around.

This work was funded by the University Research Project Grant (PIACERI Found–NATURE-OA–2020–2022), Department of Biomedical and Biotechnological Sciences (BIOME-TEC), University of Catania, Italy.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declare no conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Psychology and the Extreme Sport Experience

- First Online: 20 September 2016

Cite this chapter

- Eric Brymer 2 &

- Susan Houge Mackenzie 3

4322 Accesses

18 Citations

The term ‘extreme sports’ has become synonymous with a variety of nontraditional adventure experiences. Terminologies such as ‘whiz sports’, ‘free sports’, ‘adventure sports’, ‘lifestyle sports’, ‘action sports’, ‘alternative sports’ and ‘extreme sports’ are often used interchangeably. One disadvantage of this proliferation is that accompanying definitions are imprecise or misleading. For example, white-water kayaking on grade two of the universal grading system can feel exciting and adventurous, but the results of an accident or mistake would be relatively innocuous in comparison to the consequences of an accident or mistake on grade six water. At the highest levels of difficulty, death is a real possibility. In addition to these semantic issues, theories used to explain extreme sport participation typically portray participants as risk or adrenaline seekers. Theorists have explained participants’ motivations through a range of analytical frameworks, including edgework, sensation seeking, psychoanalysis, neotribe or subcultural formation and masculinity theory. These risk-focused accounts are often formulated by non-participants and supported by theory-driven methodologies that may not fully capture the actual lived experiences of extreme sport participants. Problems with traditional approaches to studying extreme sports include (1) research revealing characteristics and statistics that are incongruent with traditional risk and sensation-seeking accounts, (2) a myopic focus on risk-seeking that largely ignores other key motives and benefits and (3) theory-driven perspectives that do not fully reflect the lived experiences of participants. In this chapter, the authors explore the psychology of extreme sports with the aim of illuminating additional perspectives on extreme sport experiences and motivations beyond risk and sensation seeking.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

- Durable hardcover edition

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

The Mid-life ‘Market’ and the Creation of Sporting Sub-cultures

The Complexity of Sport-as-Leisure in Later Life

Positive Psychology and Sport

American Sports Data. “Generation Y” drives increasingly popular “extreme” sports. Sector Analysis Report. http://www.americansportsdata.com/pr-extremeactionsports.asp . Accessed on Nov 2002.

Pain MT, Pain MA. Essay: risk taking in sport. Lancet. 2005;366(1):33–4.

Article Google Scholar

Puchan H. Living ‘extreme’: adventure sports, media and commercialisation. J Commun Manag. 2004;9(2):171–8.

Brymer E. Extreme dude: a phenomenological exploration into the extreme sport experience. Wollongong: Doctoral Dissertation-University of Wollongong; 2005. Retrieved from http://ro.uow.edu.au/theses/379 .

Celsi RL, Rose RL, Leigh TW. An exploration of high-risk leisure consumption through skydiving. J Consum Res. 1993;20:1–23.

Soreide K, Ellingsen C, Knutson V. How dangerous is BASE jumping? An analysis of adverse events in 20,850 jumps from the Kjerag Massif, Norway. J Trauma. 2007;62(5):1113–7.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Stookesberry B. New waterfall world record. Canoe & Kayak. 2009. http://canoekayak.com/whitewater/kayaking/new-waterfall-record/ .

Warshaw M. Maverick’s: the story of big-wave surfing. San Francisco: Chronicle Books; 2000.

Google Scholar

Schneider M. Time at high altitude: experiencing time on the roof of the world. Time Soc. 2002;11(1):141–6.

Bennett G, Henson RK, Zhang J. Generation Y’s perceptions of the action sports industry segment. J Sport Manage. 2003;17(2):95–115.

Davidson L. Tragedy in the adventure playground: media representations of mountaineering accidents in New Zealand. Leis Stud. 2008;27(1):3–19.

Pollay RW. Export “A” ads are extremely expert, eh? Tob Control. 2001;10:71–4.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Rinehart R. “Babes & Boards”: opportunities in new millennium sport? J Sport Soc Issues. 2005;29:232–55.

Rinehart R. Emerging arriving sports: alternatives to formal sports. In: Coakle J, Dunning E, editors. Handbook of sports studies. London: Sage; 2000. p. 501–20.

Brymer E. Extreme sports: theorising participation – a challenge for phenomenology. Paper presented at the ORIC research symposium. University of Technology, Sydney; 2002:25.

Delle Fave A, Bassi M, Massimini F. Quality of experience and risk perception in high-altitude climbing. J Appl Sport Psychol. 2003;15:82–98.

Lambton D. Extreme sports flex their muscles. Allsport. 2000;49:19–22.

Olivier S. Moral dilemmas of participation in dangerous leisure activities. Leis Stud. 2006;25(1):95–109.

Pizam A, Reichel A, Uriely N. Sensation seeking and tourist behavior. J Hosp Leis Mark. 2002;9(3/4):17–33.

Self DR, Henry ED, Findley CS, Reilly E. Thrill seeking: the type T personality and extreme sports. Int J Sport Manage Mark. 2007;2(1–2):175–90.

Simon J. Taking risks: extreme sports and the embrace of risk in advanced liberal societies. In: Baker T, Simon J, editors. Embracing risk: the changing culture of insurance and responsibility. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2002. p. 177–208.

Rossi B, Cereatti L. The sensation seeking in mountain athletes as assessed by Zuckerman’s sensation seeking scale. Int J Sport Psychol. 1993;24:417–31.

Zuckerman M. Are you a risk taker. Psychology Today. 2000:130.

Hunt JC. Divers’ accounts of normal risk. Symb Interact. 1995;18(4):439–62.

Apter MJ. The dangerous edge: the psychology of excitement. New York: Free Press; 1992.

Kerr JH. Arousal-seeking in risk sport participants. Personal Individ Differ. 1991;12(6):613–6.

Lyng S, Young K. Risk-taking in sport: edgework and the reflexive community. In: Atkinson M, editor. Tribal play: subcultural journeys through sport. Bingley: Emerald; 2008. p. 83–109.

Chapter Google Scholar

Zuckerman M. Sensation seeking: beyond the optimal level of arousal. Hillsdale: Erlbaum;1979;27:510.

Schroth ML. A comparison of sensation seeking among different groups of athletes and nonathletes. Personal Individ Differ. 1995;18(2):219–22.

Zuckerman M. Experience and desire: a new format for sensation seeking scales. J Behav Assessment. 1984;6(2):101–14.

Zuckerman M, Bone RN, Neary R, Mangelsdorff D, Brustman B. What is the sensation seeker? Personality trait and experience correlates of the sensation seeking scales. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1972;39(2):308–21.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Schrader MP, Wann DL. High-risk recreation: the relationship between participant characteristics and degree of involvement. J Sport Behav. 1999;22(3):426–31.

Zarevski P, Marusic I, Zolotic S, Bunjevac T, Vukosav Z. Contribution of Arnett’s inventory of sensation seeking and Zuckerman’s sensation seeking scale to the differentiation of athletes engaged in high and low risk sports. Personal Individ Differ. 1998;25:763–8.

Goma M. Personality profiles of subjects engaged in high physical risk sports. Personal Individ Differ. 1991;12(10):1087–93.

Slanger E, Rudestam KE. Motivation and disinhibition in high risk sports: sensation seeking and self-efficacy. J Res Pers. 1997;31(3):355–74.

Apter MJ. Motivational styles in everyday life: a guide to reversal theory. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2001.

Book Google Scholar

Frey KP. Reversal theory: basic concepts. In: Kerr JH, editor. Experiencing sport: reversal theory. New York: Wiley; 1999. p. 3–17.

Apter MJ. The experience of motivation: the theory of psychological reversals. London: Academic; 1982.

Apter MJ. Phenomenological frames and the paradoxes of experience. In: Kerr JH, Murgatroyd SJ, Apter MJ, editors. Advances in reversal theory. Amsterdam: Swets & Zeitlinger; 1993. p. 27–39.

Shoham A, Rose GM, Kahle LR. Practitioners of risky sports: a quantitative examination. J Bus Res. 2000;47(3):237–51.

Kerr JH, Houge Mackenzie S. Multiple motives for participating in adventure sports. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2012;13(5):649–57.

Lyng S. Sociology at the edge: social theory and voluntary risk taking. In: Lyng S, editor. Edgework: the sociology of risk-taking. Abingdon: Routledge; 2005. p. 17–49.

Lois J. Peaks and valleys: the gendered emotional culture of edgework. Gend Soc. 2001;15(3):381–406.

Lyng S. Edgework: a social psychological analysis of voluntary risk taking. AJS. 1995;4:851–86.

Stranger M. The aesthetics of risk. Int Rev Sociol Sport. 1999;34(3):265–76.

Farley F. The type-T personality. In: Lipsitt L, Mitnick L, editors. Self-regulatory behavior and risk taking: causes and consequences. Norwood: Ablex Publishers; 1991.

Hunt JC. Straightening out the bends. AquaCorps. 1993;5:16–23.

Hunt JC. The neutralisation of risk among deep scuba divers: Unpublished; 1995.

Hunt JC. Diving the wreck: risk and injury in sport scuba diving. Psychoanal Q. 1996;65:591–622.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Hunt JC. Why some of us don’t mind being in deep water. Star Ledger. 1998;16.

Terwilliger C. Type ‘T’ personality. Denver Post. 1998;1:4–5.

Milovanovic D. Edgework: a subjective and structural model of negotiating boundaries. In: Lyng S, editor. Edgework: the sociology of risk-taking. Abingdon: Routledge; 2005. p. 83–109.

Brymer E. Extreme sports as a facilitator of ecocentricity and positive life changes. World Leis J. 2009;51(1):47–53.

Brymer E. Risk and extreme sports: a phenomenological perspective. Ann Leis Res. 2010;13(1–2):218–39.

Brymer E, Downey G, Gray T. Extreme sports as a precursor to environmental sustainability. J Sport Tour. 2009;14(2–3):1–12.

Brymer E, Oades LG. Extreme sports: a positive transformation in courage and humility. J Humanist Psychol. 2009;49(1):114–26.

Brymer E, Schweitzer R. Extreme sports are good for your health: A phenomenological understanding of fear and anxiety in extreme sports. J Health Psychol. 2012;18(4):477–87.

Brymer E, Schweitzer R. The search for freedom in extreme sports: a phenomenological exploration. Psychol Sport Exerc. 2013;14(6):865–73. doi: 10.1016/j.psychsport.2013.07.004 .

Willig CA. Phenomenological investigation of the experience of taking part in ‘Extreme Sports’. J Health Psychol. 2008;13(5):690–702.

Storry T. The games outdoor adventurers play. In: Humberstone B, Brown H, Richards K, editors. Whose journeys? The outdoors and adventure as social and cultural phenomena. Penrith: The Institute for Outdoor Learning; 2003. p. 201–28.

Ogilvie BC. The sweet psychic jolt of danger. Psychol Today. 1974;8(5):88–94.

Swann H, Singleman G. Baseclimb 3 – the full story 2007. http://www.baseclimb.com/About_BASEClimb3.htm .

Muir J. Alone across Australia. Camberwell: Penguin Books Australia; 2003.

Privette G. Peak experience, peak performance, and flow: a comparative analysis of positive human experiences. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1983;45(6):1361–8.

Csikszentmihalyi M. The flow experience and its significance for human psychology. In: Csikszentmihalyi M, Csikszentmihalyi I, editors. Optimal experience: psychological studies of flow in consciousness. New York: Cambridge University Press; 1988. p. 15–35.

Csikszentmihalyi M. Beyond boredom and anxiety: experiencing flow in work and play (25th Anniversary Edition ed.) San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2000.

Csikszentmihalyi M. Beyond boredom and anxiety. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1975. p. 74–97.

Young J, Pain M. The zone an empirical study. Online J Sport Psychol. 1999;1(3):1–8.

Jackson SA. Factors influencing the occurrence of flow states in elite athletes. J Appl Sport Psychol. 1995;7:138–66.

Jackson SA. Toward a conceptual understanding of the flow experience in elite athletes. Res Q Exerc Sport. 1996;67(1):76–90.

Kimiecik JC, Harris AT. What is enjoyment: a conceptual/definitional analysis with implications for sport and exercise psychology. J Sport Exerc Psychol. 1996;18(3):247–63.

Maslow AH. Religions, values and peak-experiences. Harmondsworth: Penguin; 1977. p. 15.

Panzarella R. The phenomenology of aesthetic peak experiences. J Humanist Psychol. 1980;20(1):69–85.

Lipscombe N. The relevance of the peak experience to continued skydiving participation: a qualitative approach to assessing motivations. Leis Stud. 1999;18:267–88.

Brymer E, Gray T. Dancing with nature: rhythm and harmony in extreme sport participation. Adventure Educ Outdoor Learn. 2010;9(2):135–49.

Brymer E, Gray T. Developing an intimate “relationship” with nature through extreme sports participation. Loisir. 2010;34(4):361–74.

Houge Mackenzie S, Hodge K, Boyes M. Expanding the flow model in adventure activities: a reversal theory perspective. J Leis Res. 2011;43(4):519–44.

Houge Mackenzie S, Hodge K, Boyes M. The multiphasic and dynamic nature of flow in adventure experiences. J Leis Res. 2013;45(2):214–32.

Ravizza K. Peak experiences in sport. J Humanist Psychol. 1977;17:35–40.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Sport, Leeds Beckett University, Leeds, UK

Eric Brymer

Department of Recreation, Park, and Tourism Administration, California State Polytechnic University, San Luis Obispo, Pomona, CA, USA

Susan Houge Mackenzie

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Eric Brymer .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Local Health Trust of Romagna Department of Diagnostic Imaging, S. Maria delle Croci Hospital, Ravenna, Italy

Francesco Feletti

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2017 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this chapter

Brymer, E., Houge Mackenzie, S. (2017). Psychology and the Extreme Sport Experience. In: Feletti, F. (eds) Extreme Sports Medicine. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-28265-7_1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-28265-7_1

Published : 20 September 2016

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-319-28263-3

Online ISBN : 978-3-319-28265-7

eBook Packages : Medicine Medicine (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

The significance of extreme sports: a qualitative analysis

Related Papers

World Leisure Journal

Eric Brymer

Currently, there are various definitions for extreme sports and researchers in the field have been unable to advance a consensus on what exactly constitutes an ‘extreme’ sport. Traditional theory-led explanations, such as edgeworks, sensation seeking and psychoanalysis, have led to inadequate conceptions. These frameworks have failed to capture the depth and nuances of experiences of individuals who refute the notions of risk-taking, adrenaline- and thrill-seeking or death-defiance. Instead, participants are reported to describe experiences as positive, deeply meaningful and life-enhancing. The constant evolution of emerging participation styles and philosophies, expressed within and across distinguishable extreme sport niches, or forms of life, and confusingly dissimilar definitions and explanations, indicate that, to better understand cognitions, perceptions and actions of extreme sport participants, a different level of analysis to traditional approaches needs to be emphasized. This paper develops the claim that a more effective definition, reflecting the phenomenology, and framework of an ecological dynamics rationale, can significantly advance the development of a more comprehensive and nuanced future direction for research and practice. Practical implications of such a rationale include study designs, representative experimental analyses and developments in coaching practices and pedagogical approaches in extreme sports. Our position statement suggests that extreme sports are more effectively defined as emergent forms of action and adventure sports, consisting of an inimitable person-environment relationship with exquisite affordances for ultimate perception and movement experiences, leading to existential reflection and self-actualization as framed by the human form of life.

Frontiers in Psychology

Prof. Juergen Beckmann, PhD

Journal of Leisure Research

Tony Morris

Journal of Health Psychology

Robert Schweitzer

Journal of Sport and Social Issues

Michele K Donnelly

Sport in Society

Jean-Charles Lebeau

Hatice Dilhun Sukan

The purpose of this study is to analyze extreme sports perception of students currently studying at Muğla Sıtkı Koçman University. A total of 75 students took part in this study that was conducted in line with qualitative research method. As a result of 10 focus group interviews organized among groups of 7 participants, it was identified that the very first emotions felt upon hearing the statement 'extreme sports' had been adrenalin, sensation, risk, action, fear, courage, speed, passion and extraordinariness. Extreme sports activities are naturally perceived as the kind of sport activities that involve an element of danger. In a number of extreme sports viz. skydiving, hang gliding and parachuting it was identified that primary motivational factors had been sensation and adventure seeking. The first choice of students who were extreme-activities enthusiasts was reported as paragliding ensued by rafting, mountain biking, skiing, kite surfing and climbing respectively. One of...

Susan Houge Mackenzie

RELATED PAPERS

Library Philosophy and Practice (e-journal)

Sunday Tunmibi

Juha-Matti Katajajuuri

Dr Habib Zaman Khan

Revista de Educación Técnica

Diego Armando Trujillo Toledo

GUSTAVO DOMINGUEZ

Brian Novak

David Voegeli

Archivos de cardiologia de Mexico

Aylen Pérez

International Journal of Data and Network Science

RAENDHI RAHMADI

Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care

ajaya Upadhyaya

Meriem Meriem

Journal of Knowledge Management

Willie Wang

Studi emigrazione

Matteo Sanfilippo

Semina: Ciências Agrárias

MARIA REGINA SARKIS PEIXOTO JOELE

Journal of Applied Physiology

Mary Proctor

Journal of Information Assurance & Cybersecurity

Ernesto Alejandro Hernández Escobedo

International Journal of Environmental and Agriculture Research

Aman Kumar Gupta

Roberta Scaramussa da Silva

Sports Medicine - Open

Sándor Sáfár

Computer Languages, Systems & Structures

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

- Open access

- Published: 18 April 2017

Injuries in extreme sports

- Lior Laver 1 ,

- Ioannis P. Pengas 2 &

- Omer Mei-Dan 3 , 4

Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery and Research volume 12 , Article number: 59 ( 2017 ) Cite this article

33k Accesses

34 Citations

23 Altmetric

Metrics details

Extreme sports (ES) are usually pursued in remote locations with little or no access to medical care with the athlete competing against oneself or the forces of nature. They involve high speed, height, real or perceived danger, a high level of physical exertion, spectacular stunts, and heightened risk element or death.

Popularity for such sports has increased exponentially over the past two decades with dedicated TV channels, Internet sites, high-rating competitions, and high-profile sponsors drawing more participants.

Recent data suggest that the risk and severity of injury in some ES is unexpectedly high. Medical personnel treating the ES athlete need to be aware there are numerous differences which must be appreciated between the common traditional sports and this newly developing area. These relate to the temperament of the athletes themselves, the particular epidemiology of injury, the initial management following injury, treatment decisions, and rehabilitation.

The management of the injured extreme sports athlete is a challenge to surgeons and sports physicians. Appropriate safety gear is essential for protection from severe or fatal injuries as the margins for error in these sports are small.

The purpose of this review is to provide an epidemiologic overview of common injuries affecting the extreme athletes through a focus on a few of the most popular and exciting extreme sports.

The definition of extreme sports (ES) inhabits any sports featuring high speed, height, real or perceived danger, a high level of physical exertion, and highly specialized gear or spectacular stunts and involves elements of increased risk. These ES activities tend to be individual and can be pursued both competitively and non-competitively [ 1 ]. They often take place in remote locations and in variable environmental conditions (weather, terrain) with little or no access to medical care [ 2 ], and even if medical care is available, it usually faces challenges related to longer response and transport times, access to few resources, limed provider experience due to low patient volume, and more extreme geographical and environmental challenges [ 3 ].

Examples of popular ES include BMX (Bicycle Motorcross) and mountaineering; hang-gliding and paragliding; free diving; surfing (including wave, wind, and kite surfing) and personal watercraft; whitewater canoeing, kayaking, and rafting; bungee jumping, BASE ( B uilding, A ntenna, S pan and E arth) jumping, and skydiving; extreme hiking and skateboarding; mountain biking; in-line skating; ultra-endurance races; alpine skiing and snowboarding; and ATV ( A ll- T errain V ehicle) and motocross sports [ 4 ].

In the last two decades, there has been a major increase in both the popularity and participation in ES, with dedicated TV channels, Internet sites, high-rating competitions, and high-profile sponsors drawing more participants [ 5 – 7 ]. The popularity of ES has been highlighted in recent years by the success of the X-games, an Olympic-like competition showcasing the talents in ES.

Participation in ES is associated with risk of injury or even death, and therefore, the extreme athlete—amateur or professional—and the medical personnel treating these athletes must consider the risk of injury and measures for injury prevention.

Recent data suggest that the risk and severity of injury in some ES is unexpectedly high [ 8 ].

Medical personnel treating the ES athlete need to be aware that there are numerous differences which must be appreciated between the common traditional sports and this newly developing area. These relate to the temperament of the athletes themselves, the particular epidemiology of injury, the initial management following injury, treatment decisions, and rehabilitation.

The purpose of this chapter is to provide an epidemiologic overview of the available literature on common injuries affecting the extreme athletes, the risk of their occurrence, and available prevention measures in this athletic population.

Epidemiology of extreme sports injuries

Despite great evolution in traditional sports epidemiology, injury mechanisms in ES are less understood. Higher injury rates are seen in two groups: new and inexperienced athletes who have just started engaging in extreme sports and experienced extremists [ 4 ]. In some of these ES, we do not have a clear picture of the injury pattern due to lack of formal recorded events. What we do observe is an injury increase during competitions rather than training—a trend well recognized in common team sports [ 9 , 10 ] as athletes are trying to push their limits even further for prizes, audience, or fame.

Specific extreme sports and their associated injuries

Skydiving is a major air sports of parachuting from an aircraft, the International Parachuting Commission (IPC) reported in 2009 approximately 5.5 million jumps, made by almost one million jumpers in 40 countries [ 11 ], including tandem jumps. The reported number of jumpers self operating their equipment added up to some 220,000 skydivers performing some 4.7 million skydives [ 12 ], with the majority of jumps being performed by a small number of skydivers whereas a larger number of participants perform fewer jumps [ 13 – 17 ].

Since the late 1980s, a few epidemiological studies have been conducted in order to establish the injury and fatality rates associated with the sport. Fatalities are seen more frequently in those who are considered “expert” or “seasoned” jumpers 60 vs. 20% with 71% occurring where the skydiver had at least one good parachute on, with the majority of fatalities (79%) been caused by human error [ 12 ].

Barrows et al. documented jumping incidents during two consecutive world free fall skydiving conventions in Illinois in 2000–2001 [ 13 ]. They followed 8976 skydivers making 117,000 skydives, in 20 days, indicating a total injury rate of 170 per 100,000 jumps while only 30% of those required a visit to an emergency department and as few as 10% continued to hospital admission. Most, 66% of the injuries were considered minor with 32% of these were abrasions and contusions and 22% lacerations. Of the jumpers who visited the emergency department for follow-up treatment, half suffered from extremity trauma which was related to lower extremity in 80% of patients with a rate of 0.5 fractures per 100,000 jumps.

Westman evaluated the skydiving injury rate during five consecutive years and more than half a million jumps in Sweden [ 18 ]. The incidence of non-fatal events was found to be 48 per 100,000 jumps (or 2100 jumps per incident as total or 3200 jumps per licensed jumpers), and 88% of those occurred around the landing with 51% of injuries involved the lower extremities, 19% involved the upper extremities, 18% involved the back and spine, and 7% involved the head, with 41% of the injuries categorized as minor, 47% as moderate, and 12% as severe. Most serious injuries were experienced by licensed skydivers while students in training had a six times higher injury rate. Interestingly, women over presented with injuries in this study, and they also had a higher proportion of landing injuries than men.

Although many parameters and participants may have changed over the last 20 years, injury rates remain similar. Modern equipment has decreased overall morbidity and mortality, but it has also led to faster landings with increased limb injuries.

BASE jumping

BASE jumping (“BASE” stands for B uilding, A ntenna, S pan—a bridge, arch, or dome, and E arth—a cliff or other natural formation often less than 500 ft above ground level) has around 3000 active members; it is considered the most dangerous adventure sports in the world and a skydiving offshoot using specially adapted parachutes to jump from fixed objects (Fig. 1 ).

BASE jumping. With permission and courtesy of Omer Mei-Dan

Very few studies have been conducted on this small unique population. Soreide et al. determined that BASE jumping is associated with a five- to eightfold risk for fatality or injury when compared to regular skydiving [ 19 ]. The fatality rate associated with BASE jumping was found to be 0.4 per 1000 jumps from a single site [ 19 ], although lacking information on demographic characteristics or jumpers’ experience level. In a study by Monasterio and Mei-Dan among 35 experienced BASE jumpers [ 20 ], an estimated injury rate of 0.4% was found in 9914 jumps, a finding similar to Soreide’s results [ 19 ]. Twenty-one (60%) jumpers in that study were involved in 39 accidents. The majority of accidents (28 accidents—72%) involved the lower limbs, 12 (31%) involved the back\spine, 7 (18%) the upper limb, and 1 (3%) was a head injury. It seems the sports attracts predominantly male participants. In Monasterio and Mei-Dan’s study, 75% of injuries were categorized as moderate or severe, as opposed Soreide’s series where most injuries were considered minor [ 20 ]. This could be explained by the fact that the single high site (1000 m) studied in Soreide’s series offered relatively safe jumping conditions allowing greater speed generation before parachute deployment and controlled landing. The rate of injuries requiring hospitalization in Monasterio and Mei-Dan’s study was 294 per 100,000 jumps and 16 times higher compared to the rate of such injuries in free fall skydiving found by Burrows et al. (18 per 100,000 jumps) [ 13 ]. A more recent study by Mei-Dan et al. analyzing fatality rates associated with wingsuit use in BASE jumpers showed a growing pattern of wingsuit-related fatalities, with 49% wingsuit-related fatalities between 2008 and 2011 and 90% in the first 8 months of 2013 compared to 16% between 2002 and 2007 [ 21 ]. Most fatalities occurred in the summer period in the northern hemisphere and were attributed to cliff or ground impact, being mostly the result of flying path miscalculations [ 21 ].

Climbing is an adventure sports which has developed from alpine mountaineering. Its popularity has vastly grown in the past three decades, with the introduction of indoor climbing gyms and climbing walls, becoming globally spread and evolved to new categories like ice climbing, bouldering, speed climbing, and aid climbing reaching an estimated two million participants in Europe and about nine million in the USA [ 22 ] (Fig. 2 ).

Bouldering. With permission and courtesy of Volker Schoffl

There are various disciplines encapsulated under the umbrella of climbing; some are less risky than others, with sports climbing or free climbing among the safest. A cross-sectional survey on rock climbing showed a lower frequency injury rate compared to football and horse riding [ 23 ], but with more catastrophic or fatal consequences.

Most studies show that the incidence of overuse injuries is associated with climbing frequency and difficulty [ 24 , 25 ]. Most injuries are sustained by the lead climber, with falls being the most common mechanism of acute injuries [ 26 ]. Overall, most registered injuries in climbing studies are of minor severity. The fatality rate reported in climbing ranges from 0 to 28% climbers in various studies [ 27 ]. This wide range could be explained by varying methodology and data collection techniques in different series.

In indoor climbing, injury rates are much lower with 0.027–0.079 injuries/1000 h of participation and fatalities are very rare [ 28 ]. Overuse injuries are more common in this discipline, most commonly involving the upper extremities—mainly finger injuries. Although climbing relies on the synchronized and optimal function of the whole body, activity and performance are primarily limited by finger and forearm strength. Various gripping techniques lead to transmission of extremely high forces to the fingers, making overuse injuries of the fingers and hands the most common complaints in rock climbers [ 24 , 25 , 28 – 31 ]. Some injuries, such as flexor tendon pulley ruptures or the lumbrical shift syndrome, are very unique and specific for the sports and are rarely seen in other patient populations [ 24 ]. Very little data exists for ice climbing, and although severe injuries and fatalities occur, most recognized injuries are of minor severity and are comparable with other outdoor sports [ 27 , 32 ].

Most studies on mountaineering report fatality/injury rates per 1000 climbers or 1000 summits, making it difficult to compare to the more common 1000 h of sports participation used in other disciplines. In mountaineering, additional environmental factors (avalanches, crevasses, altitude-induced illnesses with neurological dysfunction, etc.) can directly influence injuries and fatalities [ 33 ]. In high altitudes, it is important to also follow the prevalence of altitude illness, estimated between 28 and 34% above 4000 m [ 34 , 35 ] and can be a major cause of injury, accident, or even death [ 36 – 38 ].

The sports of wave surfing is ever growing with a huge market involved, commercialization of surfing apparel and the surfing lifestyle, fashion trends, and media coverage. In 2009, it was estimated that there were more than 2.4 million surfers in the USA [ 39 ]. Despite being one of the most popular outdoor sports in the world, less than ten studies have been conducted on wave surfing.

Surfing is considered relatively safe compared to more traditional sports. A survey of self-reported injuries in Australia in 1983 found 3.5 “moderate to severe” injuries (resulting in lost days of surfing or requiring medical care) per 1000 surfing days [ 40 ]. The most common injuries requiring medical attention or resulting in inability to surf were lacerations (41%) and soft-tissue injuries (35%). A recent Australian survey found a rate of 2.2 significant injuries per 1000 surfing days [ 41 ] equating to 0.26 injuries/surfer/year, of those 45.2% were caused by collision with another surfer or surfboard. Distribution of lacerations, sprains, and contusions were similar to other reported rates, but they also reported 11% dislocation rate and 9% fractures.

Nathanson et al. evaluated acute competitive surfing injuries at 32 professional and amateur surfing contests worldwide between 1999 and 2005 [ 42 ]. The injury rate found was 5.7 per 1000 athlete exposures, or 13 per 1000 h of competitive surfing, with 6.6 significant injuries per 1000 h of competitive surfing. This injury rate compares favorably to those found in American collegiate football (33 per 1000 h), soccer (18 per 1000 h), and basketball (9 per 1000 h) where similar methods of data collection and injury definition were used [ 43 ]. The relative injury risk was calculated to be 2.4 times greater when surfing in waves overhead or bigger and 2.6 times greater when surfing over a rock or reef bottom.

In a Web site-based survey, 1348 individuals reported 1237 acute injuries and 477 chronic injuries [ 44 ]. Lacerations accounted for 42% of all acute injuries, contusions 13%, sprains/strains 12%, and fractures 8%. Thirty-seven percent of acute injuries were to the lower extremity, and 37% to the head and neck. Fifty-five percent of injuries resulted from contact with one’s own board, 12% from another surfer’s board, and 17% from the sea floor. This data correlates well with previous reports showing high incidence of lacerations caused by the sharp fin, the tail, or the nose of the surfboard. An interesting finding showed a considerable proportion of head injury, in contrast to the fact very few surfers use protective headgear [ 44 , 45 ].

Fatality rates are unknown in surfing. Reports from Hawaii from 1993 to 1997 found that bodyboarders and surfers accounted for 17 of 238 ocean-related drownings [ 46 ]. This data includes fatal shark attacks. As 50% of a surfer’s time is spent paddling and 45% is spent remaining still, while only 3–5% is spent actually riding waves, most overuse injuries derive from paddling [ 47 , 48 ]. Other data found overuse injuries to the shoulder (18%), back (16%), neck (9%), and knee (9%) [ 42 ].

Injury prevention in surfing is practiced by following basic safety recommendations such as maintaining adequate swimming skills (the ability to swim 1 km in less than 20 min and being comfortable swimming alone in the ocean) [ 49 ], familiarizing with the surfing environment and conditions (entry and points, currents, and underwater hazards), avoiding surfing to exhaustion, and safely practicing breath-holding training. Using adequate equipment is also essential such as temperature-appropriate wetsuits protecting against hypothermia, protected, rounded, and shock absorbing surfboard noses and fins trailing edges, and a board leash to keep the surfer’s board close at hand, and the board can be used as a flotation device should a surfer become exhausted or injured.

Skiing and snowboarding

Skiing and snowboarding are the two main piste-based snow sports. With roots in Nordic (cross-country) skiing, Alpine skiing gradually evolved over time from method of transportation in Scandinavia thousands of years ago into the present recreational and competitive sport, becoming a winter Olympic sports in Garmisch in 1936, with snowboarding becoming an Olympic sports in 1998 (Fig. 3 ).

Snowboarding. With permission and courtesy of David Carlier

Although variable between resorts, currently approximately 60% of those on the slopes are Alpine skiers and 30–35% are snowboarders while the remainder perform ski boarding (snowblading) and Telemark skiing. Recent estimation report around 200 million skiers and 70 million snowboarders active in the world today.

The current risk of a recreational snow-sport-related injury is between 2 and 4 injuries per 1000 participant days [ 50 ], a risk much lower than in popular sports such as football and rugby, and has decreased steadily over recent years [ 51 ] thanks to improvements in equipment, ski area design and maintenance, and piste preparation [ 51 ]. The risk of injury from recreational Alpine skiing is generally accepted to be between 1 and 2 injuries per 1000 participant days [ 50 , 52 ].

The fracture rate from Alpine skiing is approximately 19% [ 53 ], and common sites include the clavicle, proximal humerus, and tibia. Prior to the introduction of release bindings, fractures of the lower leg were common from twisting forces transmitted unmitigated from the ski up to the lower leg. Even so, Alpine skiers are still more likely to injure their lower rather than their upper limb, with the knee joint being the single commonest site of injury among skiers, and most of these injuries are soft tissue/ligamentous in nature. (Figs. 4 and 5 ).

Injury types breakdown in Alpine skiing. From [ 69 ]. Used with publisher’s permission

Commonly injured areas in Alpine skiing. From [ 69 ]. Used with publisher’s permission

Upper limb injuries feature strongly with either the thumb or the shoulder being involved following a fall onto an outstretched hand. Thumb injuries almost exclusively affect Alpine skiers, so much so that the term “skier’s thumb” is used to describe the commonest injury—an acute radial stress to the metacarpophalangeal (MCP) joint of the thumb. The handle of the ski pole acts as a fulcrum across the MCP joint stressing the ulnar collateral ligament (UCL) [ 54 ]. If left untreated, this may lead to long-term functional disability.

The four commonest shoulder injuries to affect skiers and snowboarders are anterior dislocation of the glenohumeral joint, acromioclavicular (AC) joint disruption, clavicle fracture, and fracture of the proximal humerus. The incidence of shoulder injuries is higher in snowboarders [ 55 ].

The risk of injury from snowboarding is generally estimated at about twice that of Alpine skiing and currently stands at between 2 and 4 injuries per 1000 participant days [ 52 ]. Snowboarders are more likely to injure their upper limb than their lower limb [ 53 ]. Unlike skiers, when losing balance, snowboarders cannot step out a leg to regain balance. As a result, falls due to loss of balance are frequent, and not surprisingly, beginner snowboarders are at highest risk. This commonly results in falls on an outstretched hand and places the upper limb, and the wrist joint in particular, at high risk of injury [ 56 ]. The fracture rate among snowboarders is twice that of Alpine skiers [ 53 ], caused largely by the high rate of wrist fractures (up to 33% of all injuries [ 57 ].

Muscle and ligament strain/sprains are still common as are contusions from off-balance falls. Snowboarders suffer a higher rate of shoulder joint injuries due to an increased tendency to fall onto the upper limb [ 53 ]. Jumps and other aerial maneuvers, commonly performed in snowboarding, are associated with a relatively small but definite risk of injury to the spine [ 58 – 60 ]. Figure 6 illustrates injury types in snowboarding.

Injury types breakdown in snowboarding. From [ 69 ]. Used with publisher’s permission

The injury risk among professional skiers and snowboarders is approximately three times that of recreational participants [ 61 ] and has been calculated to be 17 injuries per 1000 ski runs [ 62 ]. Almost one third of injuries among professional athletes were classified as severe, leading to an absence from participation of more than 28 days [ 63 ]. The knee is the commonest injury area among competitive skiers and snowboarders [ 61 – 63 ].

Knee injuries account for about one third of all skiing injuries. Most are minor soft tissue sprains. The medial collateral ligament (MCL) is commonly injured as a result of valgus force to the knee as the ski unintentionally splays the lower leg outward. Most grade 1 and 2 injuries will settle with conservative treatment. The most serious soft tissue knee injury involves the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL). This important ligament may be injured in isolation or in combination with other structures. While it is possible to ski without an ACL, this requires considerable effort and rehabilitation to maintain knee stability, muscle bulk, and proprioception. Most orthopedic surgeons recommend ACL reconstruction for those who wish to ski at or above an intermediate level. Knee injuries among snowboarders are much less common and usually result from direct trauma to the anterior aspect of the knee.

The fatality risk in snow sports is even lower at one death per 1.57 million participant days [ 64 ]. This equates to approximately 39 traumatic deaths per year in the USA out of a total of almost 60 million participant days (source: http://www.nsaa.org/ ). These fatality rates are much lower compared to other popular recreational activities such as swimming and cycling [ 64 ]. The commonest cause of a traumatic snow-sport-related death is a high-speed collision with a static object (tree, pylon, or another person) [ 65 , 66 ]. Many of these deaths involve head injuries [ 66 ]. Non-traumatic causes of death on the slopes include ischemic heart disease, hypothermia, and medical events such as acute severe asthma attacks [ 65 ]. A less frequent but important mechanism of death is the so-called non-avalanche-related snow immersion death (NARSID), also known as a “tree well death” [ 66 , 67 ], when skiers/snowboarders fall into a hidden pit underneath a tree. Unless the event is witnessed, self-extraction from the tree well is nearly impossible. The trapped individual tends to cause more snow to fall into the pit as they struggle to try to extract and death usually resulting from hypothermia or asphyxiation from snow falling in [ 68 ].

Conclusions

Extreme sports are increasing in popularity, being fun to participate in and exciting to watch. The management of the injured extreme sports athlete is a challenge to surgeons and sports physicians. Appropriate safety gear is essential for protection from severe or fatal injuries as the margins for error in these sports are small. However, extreme sports athletes are more likely to return to their pre-injury levels of activity than the general population following treatment.

Adventure and extreme sports. topendsports. at: http://www.topendsports.com/sport/adventure . Accessed 10 Sept 2014.

Heggie TW, Heggie TM. The epidemiology of extreme hiking injuries in volcanic environments. In: Heggie TM, Caine DJ, editors. Epidemiology of injury in adventure and extreme sports, 58. 2012. p. 130–41. Med Sport Sci. Basel, Karger.

Chapter Google Scholar

Heggie TW, Heggie TM. Saving tourists: the status of emergency medical services in California’s National Parks. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2009;7:19–24.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Mei-Dan O, Carmont MR (eds). Management of the extreme sports athlete. In: Adventure and extreme sports: epidemiology, treatment, rehabilitation and prevention. Introduction. Springer-Verlag; 2013. pp. 1–5.

Brymer E, Schweitzer R. Extreme sports are good for your health: a phenomenological understanding of fear and anxiety in extreme sport. J Health Psych. 2012;18(4):447–87.

Google Scholar

Reiman PR, Augustine SJ, Chao D. The action sports athlete. Sports Med Update 2007: July 2-8

Puchan H. Living ‘extreme’: adventure sports, media and commercialization. J Communication Management. 2004;9(2):171–8.

Article Google Scholar

Heggie TW, Caine DJ, editors. Epidemiology of injury in adventure and extreme sports, vol. 58. 2012. p. 1–172. Med Sport Sci. Basel, Karger.

Book Google Scholar

Brooks JH, Fuller CW, Kemp SP, et al. Epidemiology of injuries in English professional rugby union. Part 1: match injuries. Br J Sports Med. 2005;39(10):757–66.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Brooks JH, Fuller CW, Kemp SP, et al. Epidemiology of injuries in English professional rugby union. Part 2: training injuries. Br J Sports Med. 2005;39(10):767–75.

Riksinstruktören, 402:01 Grundläggande bestämmelser, in Swedish regulations for sport parachuting [SFF Bestämmelser Fallskärmsverksamhet; in Swedish]. Svenska Fallskärmsförbundet; 2011.

International Parachuting Commission Technical and Safety Committee. Safety report 2009. In: IPC safety reports. McNulty L, editor. Fédération Aéronautique Internationale; 2010.

Barrows TH, Mills TJ, Kassing SD. The epidemiology of skydiving injuries: world freefall convention, 2000–2001. J Emerg Med. 2005;28:63–8.

Ellitsgaard N. Parachuting injuries: a study of 110,000 sports jumps. Br J Sports Med. 1987;21:13–7.

Steinberg PJ. Injuries to Dutch sport parachutists. Br J Sports Med. 1988;22:25–30. 2006 safety report, technical and safety committee, International Parachuting Commission, FAI.

Westman A, Björnstig U. Fatalities in Swedish skydiving. Accid Anal Prev. 2005;37(6):1040–8. Epub 2005 Jul 21.

Paul S. The 2008 fatality summery – “back to the bad old days”. USPA Parachutist Mag. 2009;50(594):30–5.

Westman A, Björnstig U. Injuries in Swedish skydiving. Br J Sports Med. 2007;41(6):356–64. discussion 364.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Soreide K, Ellingsen L, Knutson V. How dangerous is BASE jumping? An analysis of adverse events in 20,850 jumps from Kjerag Massif, Norway. J Trauma. 2007;62:1113–7.

Monasterio E, Mei-Dan O. Risk and severity of injury in a population of BASE jumpers. NZMJ. 2008;121:1277.

Mei-Dan O, Monasterio E, Carmont M, Westman A. Fatalities in wingsuite BASE jumping. Wilderness Eniron Med. 2013;24(4):321–7. doi: 10.1016/j.wem.2013.06.010 .

Nelson NG, McKenzie LB. Rock climbing injuries treated in emergency departments in the US, 1990–2007. Am J Prev Med. 2009;37:195–200.

Schussmann LC, Lutz LJ, Shaw RR, Bohn CR. The epidemiology of mountaineering and rock climbing accidents. Wilderness Environ Med. 1990;1:235–48.

Schöffl VR, Schöffl I. Finger pain in rock climbers: reaching the right differential diagnosis and therapy. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2007;47:70–8.

PubMed Google Scholar

Neuhof A, Hennig FF, Schöffl I, Schöffl V. Injury risk evaluation in sport climbing. Int J Sports Med. 2011;32:794–800.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Schöffl V, Küpper T. Rope tangling injuries—how should a climber fall? Wilderness Environ Med. 2008;19:146–9.

Schöffl V, Morrison AB, Schwarz U, Schöffl I, Küpper T. Evaluation of injury and fatality risk in rock and ice climbing. Sports Med. 2010;40:657–79.

Kubiak EN, Klugman JA, Bosco JA. Hand injuries in rock climbers. Bull NYU Hosp Jt Dis. 2006;64:172–7.

Logan AJ, Makwana N, Mason G, Dias J. Acute hand and wrist injuries in experienced rock climbers. Br J Sports Med. 2004;38:545–8.

Schöffl V, Hochholzer T, Winkelmann HP, Strecker W. Pulley injuries in rock climbers. Wilderness Environ Med. 2003;14:94–100.

Schöffl V, Hochholzer T, Winkelmann HP, Strecker W. Differential diagnosis of finger pain in sport climbers. Differentialdiagnose von Fingerschmerzen bei Sportkletterern D Z Sportmed. 2003;54:38–43.

Schöffl V, Schöffl I, Schwarz U, Hennig F, Küpper T. Injury-risk evaluation in water ice climbing. Med Sport. 2009;2:32–8.

Schöffl V, Morrison A, Schöffl I, Küpper T. Epidemiology of injury in mountaineering, rock and ice climbing. In: Caine D, Heggie T, editors. Medicine and sport science—epidemiology of injury in adventure and extreme sports. Basel: Karger; 2012.

Basnyat B, Murdoch DR. High-altitude illness. Lancet. 2003;361:1967–74.

Basnyat B, Lemaster J, Litch JA. Everest or bust: a cross sectional, epidemiological study of acute mountain sickness at 4243 meters in the Himalayas. Aviat Space Environ Med. 1999;70:867–73.

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Firth PG, Zheng H, Windsor JS, Sutherland AI, Imray CH, Moore GW, Semple JL, Roach RC, Salisbury RA. Mortality on Mount Everest, 1921–2006: descriptive study. BMJ. 2008;337:a2654.

Salisbury R. The Himalayan database: the expedition archives of Elizabeth Hawley. Golden: American Alpine Club; 2004.

Salisbury R, Hawley E. The Himalayan by the numbers. 2007. www.himalayandatabase.com . Accessed 11 Sept 2012.

The Outdoor Foundation. Outdoor recreation participation report. 2010. http://www.outdoorfoundation.org/pdf/ResearchParticipation2010.pdf . Accessed 22 July 2011.

Lowdon B, Pateman N, Pitman A. Surfboard-riding injuries. Med J Aust. 1983;2:613–6.

Taylor D, Bennett D, Carter M, Garewal D, Finch C. Acute injury and chronic disability resulting from surfboard riding. J Sci Med Sport. 2004;7(4):429–37.

Nathanson A, Haynes P, Galanis D. Surfing injuries. Am J Emerg Med. 2002;20(3):155–60.

Nathanson A, Bird S, Dao L, Tam-Sing K. Competitive surfing injuries: a prospective study of surfing-related injuries among contest surfers. Am J Sports Med. 2007;35(1):113–7.

Allen RH, Eiseman B, Straehley CJ, Orloff BG. Surfing injuries at Waikiki. JAMA. 1977;237(7):668–70.

Taylor KS, Zoltan TB, Achar SA. Medical illnesses and injuries encountered during surfing. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2006;5(5):262–7.

Galanis D. Drownings in Honolulu County 1993–2000: medical and toxicological factors. http://health.hawaii.gov/injuryprevention/files/2013/09/drowning_Datachapter2007-11a-1MB.pdf . Accessed 11 June 2011.

Mendes-Villanueva A, Bishop D. Physiological aspects of surfboarding riding performance. Sports Med. 2005;35(1):55–70.

Meir R, Lowdon R, Davie A. Estimated energy expenditure during recreational surfing. Aust J Sci Med Sport. 1991;23(4):70–4.

Renneker M. Surfing: medical aspects of surfing. Phys Sportsmed. 1987;15(12):96–105.

Ekeland A, Rødven A. Skiing and boarding injuries on Norwegian slopes during the two winter seasons 2006/07 and 2007/08. Skiing Trauma and Safety 18th volume. ASTM STP. 2011;1525:139–49.

Johnson R, Ettlinger C, Shealy J. Update on injury trends in alpine skiing. Skiing trauma and safety 17th volume. J ASTM Int. 2011;1510:11–22.

Ekeland A, Sulheim S, Rodven A. Injury rates and injury types in alpine skiing, telemarking and snowboarding. Skiing trauma and safety 15th volume. ASTM STP. 2005;1464:31–9.

Langran M, Selvaraj S. Snow sports injuries in Scotland: a case–control study. Br J Sports Med. 2002;36(2):135–40.

Demirel M, Turhan E, Dereboy F, Akgun R, Ozturk A. Surgical treatment of skier’s thumb injuries: case report and review of the literature. Mt Sinai J Med. 2006;73(5):818–21.

Hedges K. Snowboarding injuries: an analysis and comparison with alpine skiing injuries. CMAJ. 1992;146(7):1146–8.

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Binet M. French prospective study evaluating the protective role of all kinds of wrist protectors for snowboarding. Presented at the 17th congress of The International Society for Skiing Safety 2007. Aviemore; 2007;31–39.

Langran M, Selvaraj S. Increased injury risk among first-day skiers, snowboarders, and skiboarders. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32(1):96–103.

Yamakawa H, Murase S, Sakai H, Iwama T, Katada M, Niikawa S, et al. Spinal injuries in snowboarders: risk of jumping as an integral part of snowboarding. J Trauma. 2001;50(6):1101–5.

Wakahara K, Matsumoto K, Sumi H, Sumi Y, Shimizu K. Traumatic spinal cord injuries from snowboarding. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34(10):1670–4.

Koo DW, Fish WW. Spinal cord injury and snowboarding—the British Columbia experience. J Spinal Cord Med. 1999;22(4):246–51.

Florenes TW. Injury surveillance in World Cup skiing and snowboarding. MD Thesis. Faculty of Medicine, University of Oslo; 2010.

Florenes TW, Bere T, Nordsletten L, Heir S, Bahr R. Injuries among male and female World Cup alpine skiers. Br J Sports Med. 2009;43(13):973–8.

Florenes TW, Nordsletten L, Heir S, Bahr R. Injuries among World Cup ski and snowboard athletes. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2012;22(1):58–66.

National Ski Areas Association. Facts about skiing/snowboarding safety. NSAA Online publications. 2016. Available at: http://www.nsaa.org/media/276230/Facts_on_Skiing__Snowboard_Safety_2016.pdf . Accessed 13 Apr 2017.

Sherry E, Clout L. Deaths associated with skiing in Australia: a 32-year study of cases from the Snowy Mountains. Med J Aust. 1988;149(11–12):615–8.

Shealy J, Johnson R, Ettlinger C. On piste fatalities in recreational snow sports in the US. Skiing trauma and safety 16th volume. ASTM STP. 2006;1474:27–34.

Cadman R. Eight nonavalanche snow-immersion deaths. A 6-year series from British Columbia ski areas. Physician Sportsmed. 1999;27(13):1–7.

Cadman R. How to stay alive in deep powder snow. Physician Sportsmed. 1999;27(13):18–9.

Langran M. Alpine skiing and snowboarding injuries. In: Adventure and extreme sports: epidemiology, treatment, rehabilitation and prevention. Introduction. Springer-Verlag; 2013. p. 37–7.

Download references

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing are not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Authors’ contributions

All authors contributed to the data collection and drafting of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Ethics approval and consent to participate, publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Trauma and Orthopaedics, University Hospital Coventry and Warwickshire, Coventry, UK

Department of Trauma & Orthopaedics, Royal Cornwall Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust, Truro, UK

Ioannis P. Pengas

CU Sports Medicine & Performance Center, Boulder, CO, USA

Omer Mei-Dan

University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora, CO, USA

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Lior Laver .

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License ( http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Laver, L., Pengas, I.P. & Mei-Dan, O. Injuries in extreme sports. J Orthop Surg Res 12 , 59 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-017-0560-9

Download citation

Received : 15 November 2016

Accepted : 15 March 2017

Published : 18 April 2017

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13018-017-0560-9

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Anterior Cruciate Ligament

- Injury Rate

- Overuse Injury

- Ulnar Collateral Ligament

- Alpine Skiing

Journal of Orthopaedic Surgery and Research

ISSN: 1749-799X

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

PERSPECTIVE article

Defining extreme sport: conceptions and misconceptions.

- 1 The London Sports Institute, Faculty of Science and Technology, Middlesex University London, London, United Kingdom

- 2 Department of Psychology, Faculty of Science and Technology, Middlesex University London, London, United Kingdom

One feature of how sport is defined is the distinction between extreme and non-extreme sport. BASE jumping is an example of an “extreme sport” because it involves a high degree of risk, whilst swimming is classified as “non-extreme” because the risks involved are minimal. This broad definition falls short of identifying the extent of risk and ignores the psychological, social-demographic and life style variables associated with engagement in each sport.

Introduction

Indeed, the lack of consistency within the term “extreme sport" means that those wishing to study this field are forced to create their own criteria as a starting point, often in a less than scientific manner. This literary review of contemporary and historical research articles raises the key question of whether the definition of extreme sport is one of risk-taking with a high chance of injury or death or whether there are additional aspects to consider such as lifestyle or a relationship to the natural environment. This review does not examine any hypotheses and is a narrative based on key papers. Due to the lack of literature on this subject area it was not thought pertinent to conduct a systematic review.

The aim of this article is twofold: firstly, to demonstrate whether the term “extreme sport” in scientific terms, has developed into a misnomer, misleading in the context of the sports it tends to encompass, secondly, to propose a revised, more accurate definition of extreme sport, reflective of the activities it encompasses in the context of other non-mainstream sports. Based on this review it is argued that a new definition of an extreme sport is one of “a (predominantly) competitive (comparison or self-evaluative) activity within which the participant is subjected to natural or unusual physical demands. Moreover, an unsuccessful outcome is “likely to result in the injury or fatality of the participant, in contrast to non-extreme sport” ( Cohen, 2016 , p. 138).

“Extreme Sport” – Challenging the Definition

The question of what is an extreme sport and whether the term “extreme sport” should be used to label particular sports can be viewed from a variety of angles. “Extreme sport” appears to be used interchangeably with “high risk sport” in much of the research literature. Both “high risk” and “extreme sport” are defined as any “sport where one has to accept a possibility of severe injury or death as an inherent part of the activity” ( Breivik et al., 1994 ). In the same manner, classification of extreme or high risk could partly be due to peak static and dynamic components achieved during competition ( Mitchell et al., 2005 ), which may result in bodily changes such as high blood pressure (e.g., Squash vs. Archery). A further classification would consider physical risk (e.g., BASE Jumping vs. Darts) as a defining feature of any “extreme or high risk sport” ( Palmer, 2002 ). However, the implication that those who engage in extreme sport are exclusively high-risk taking participants is an over simplification which requires careful consideration. Part of the difficulty in being able to define extreme sport is, according to Kay and Laberge (2002) . There are so many contradictory factors aside from risk. It is suggested here that there are spatial, emotional, individualistic and transgressive dimensions to consider in these sports. Terms such as “alternative,” “action,” “adventure,” and “lifestyle” are also used to describe extreme sport, however, none of these terms categorically encompass what extreme sport actually entails.

What is Extreme?

According to Merriam-Webster’s online dictionary (retrieved September 2018) the word extreme means: (1) Exceeding the ordinary, usual or expected. (2) Existing in a very high degree. (3) Going to a great or exaggerated lengths. Therefore, extreme as used in “extreme sport” suggests a deviation beyond what is generally viewed as “normal” or “traditional” activity and assumes participants pursue activities beyond these limits. The online Oxford University Dictionary (2018) defines “extreme sport” as “Denoting or relating to a sport performed in a hazardous environment and involving great risk.” So, the concept of “going beyond normal limits” and “risk” seem integral to what constitutes extreme sport. Booker (1998) stated that “extreme sports” were beyond the boundary of moderation; surpassing what is accounted for as reasonable – i.e., radical, and sports that are located at the outermost. Breivik et al. (1994) defined extreme sport’ as a high-risk sport where the possibility of severe injury or death is a possibility as well as integral to the sport or activity. So, the components of these definitions include: going beyond the norm of what is considered reasonable and may result in severe injury or death, i.e., high physical and/or psychological risk.

What is Sport?

Historically the definitions of sport have evolved particularly as new activities such as “BASE jumping” and “extreme mountain ironing” have emerged to challenges the perception of what sport actually is. Eysenck et al. (1982) , in their seminal review paper began by highlighting the problems inherent in the definition of sport. They used the Collins dictionary in their paper to define sport as amusement, diversion, fun, pastime, game… individual or group activity pursued for exercise or pleasure often involving the testing of physical capabilities… ( Eysenck et al., 1982 ). Arguably, this type of definition is overly inclusive, incorporating activities of amusement and pleasure whereby virtually anything that is non-work could be considered sport.

A more recent definition of sport is “all forms of physical activity which, through casual or organised participation, aimed at expressing or improving physical fitness and mental well-being, forming social relationships or obtaining results in competition at all levels” ( Council of Europe [CEE], 2001 , The European Sports Charter, revised, p. 3 – CEE). This broad definition of sport can encompass “traditional” sports such as Archery, Football, and Cricket, as well as those hitherto regarded as extreme sports such as Drag racing, BASE Jumping and Snowboarding.

Historically the CEES’s definition is not entirely new as sport has traditionally been accepted to represent a competitive task or activity engaged in by an individual or a group, which requires physical exertion and is governed by rules. Mason (1989) saw sport as “a more or less physically strenuous, competitive, recreational activity…usually…in the open air (which) might involve team against team, athlete against athlete or athlete against nature, or the clock.” Sport is generally viewed to be performed by individuals or in a group, as an organised, evaluative activity where the outcome of performance is judged by winning or losing. However, the inclusion of the word “or” in the CEES definition changes the nature of what is considered to be sport. It implies that results in competition do not need to be present and can be self evaluative or competitive. The modification of this definition allows activities such as recreational swimming or bungee jumping to now be classified as sports.

Is “Extreme Sport” the Same as “High Risk Sport?”

If “extreme sport” is the same as a “high-risk” sport then those individuals that engage in these sports should be at greater risk of injury or even death than those engaging in traditional sports ( Yates, 2015 ). When investigating the available statistics relating to extreme sport, one comes across a minefield of contradictions as the classification of injuries and/or fatalities are reported in a myriad of different ways.

A further challenge is then to set parameters using statistics of extreme sport according to risk, injury or mortality. This would require traditional sports such as cheerleading and horse riding, due to their high annual incidence of catastrophic injuries, to be classified as high-risk sports ( Turner and McCory, 2006 ). In the United Kingdom the Rugby Football Union defined injury as something that “…prevents a player from taking a full part in all training activities typically planned for that day…” (p. 7 in the England Professional Rugby Injury Surveillance Project Season , England Professional Rugby Injury Surveillance Project Season ). Mean injuries per match for 2013 were identified as 62 and mean injuries per club (including training) were 35 (p. 6 England Professional Rugby Injury Surveillance Project Season , England Professional Rugby Injury Surveillance Project Season ). Annual Rugby Union incidents around the world account for 4.6 catastrophic injuries per 100,000 each year, e.g., the risk of sustaining a catastrophic injury in Rugby Union in England (0.8/100,000 per year) are relatively lower than in New Zealand (4.2/100,000 per year), Australia (4.4/100,000 per year), and Fiji (13/100,000 per year). The risk of sustaining a catastrophic injury in other contact sports are; Ice Hockey (4/100,000 per year), Rugby League (2/100,000 per year), and American Football (2/100,000 per year) ( Gabbe et al., 2005 ; Fuller, 2008 ).

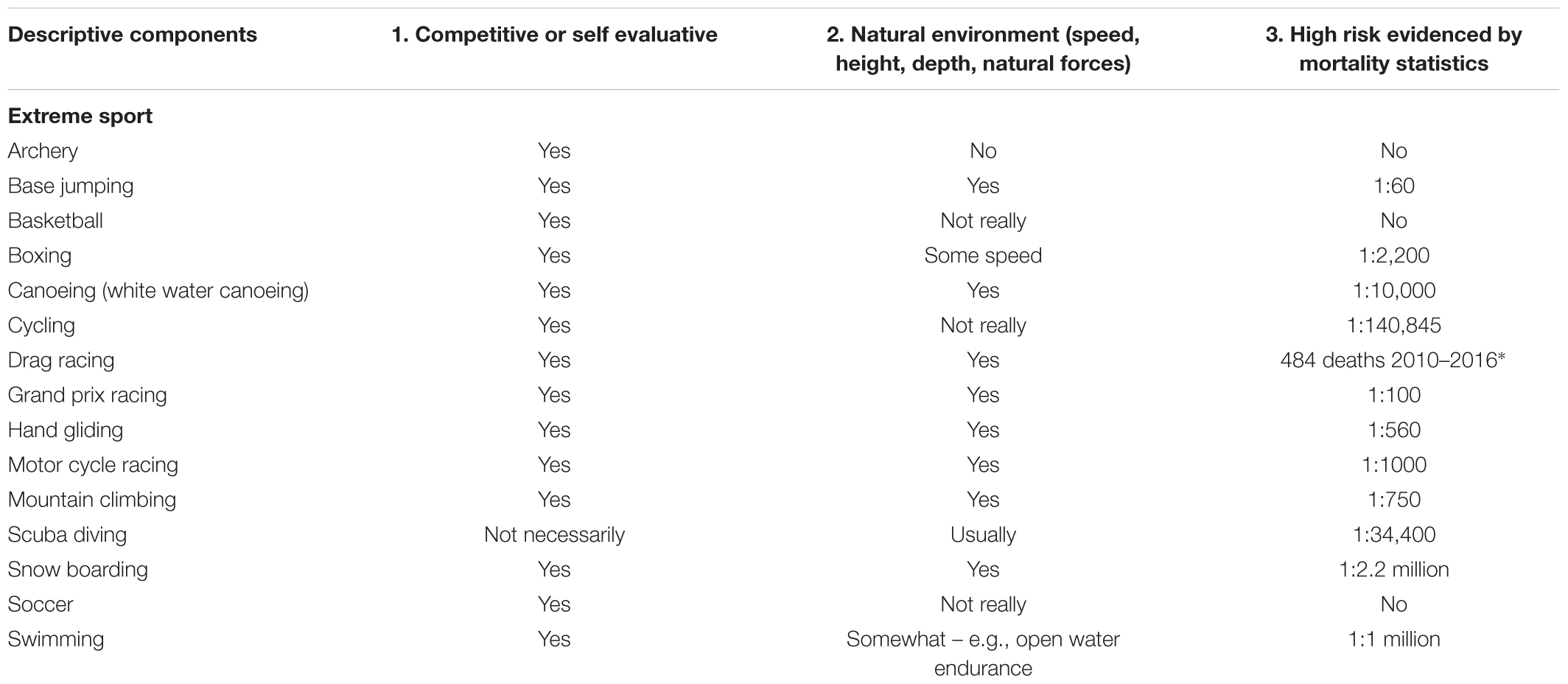

Besides mortality as a relevant and possible outcome, the link between the “extreme” nature of sport and brain damage arguably should be considered. Recently, the association between contact sports such as American Football and Rugby, combat sports such as Boxing and the team sport of Soccer (which includes heading balls), has resulting in a raised awareness of the relationship between sport and brain injuries and/or cognitive disturbance such as that found in Dementia. Negative effects on neuro-functioning in terms of cerebral blood flow, resulting in poor cognitive performance, can be prevalent in several sports, e.g., there have been recommendations from scuba diving research which suggested that scuba diving should be classified as a high-risk sport for the purpose of subjecting it to tighter controls and increased medical advice ( Slosman et al., 2004 ). Alternative research suggests that classifying a sport as “extreme” should be based solely by mortality rate ( Schulz et al., 2002 ). Mortality figures (see Table 1 ) show that whilst BASE Jumping has an extremely high mortality rate so does boxing and, somewhat surprisingly, canoeing. One may argue that employing such methods to classify sports is anything but straightforward, moreover many of the sports currently viewed as “traditional” may need further consideration as to how they could fit into a proposed working definition of extreme sport.

TABLE 1. Categorising extreme sport.

Besides physical risk May and Slanger (2000) suggest there is potentially psychological risk when engaging in high risk sport. Their findings suggest such activities can be psychologically damaging leading to elevated stress levels, extreme competitiveness and excessive perfectionism. In view of this it could be pertinent to consider the tenets of high-risk sport as both physical and psychological. In a somewhat provocative statement, Slanger and Rudestam (1997) cited extreme sport as an expression of a death wish, whereby in a slightly different manner, Brymer and Oades (2009) considered extreme sport not to be about the expression of risk but rather about the experience of approaching danger. It is also evident that many researchers conducting studies into sensation seeking have used the term “high-risk” interchangeably with “extreme sport” (e.g., Cronin, 1991 ; Gomài Freixanet, 1991 ; Breivik et al., 1994 ; Wagner and Houlihan, 1994 ).