- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

The Process of Conducting Ethical Research in Psychology

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Tom Merton / Getty Images

Earlier in psychology history, many experiments were performed with highly questionable and even outrageous violations of ethical considerations. Milgram's infamous obedience experiment , for example, involved deceiving human subjects into believing that they were delivering painful, possibly even life-threatening, electrical shocks to another person.

These controversial psychology experiments played a major role in the development of the ethical guidelines and regulations that psychologists must abide by today. When performing studies or experiments that involve human participants, psychologists must submit their proposal to an institutional review board (IRB) for approval. These committees help ensure that experiments conform to ethical and legal guidelines.

Ethical codes, such as those established by the American Psychological Association, are designed to protect the safety and best interests of those who participate in psychological research. Such guidelines also protect the reputations of psychologists, the field of psychology itself and the institutions that sponsor psychology research.

Ethical Guidelines for Research With Human Subjects

When determining ethical guidelines for research , most experts agree that the cost of conducting the experiment must be weighed against the potential benefit to society the research may provide. While there is still a great deal of debate about ethical guidelines, there are some key components that should be followed when conducting any type of research with human subjects.

Participation Must Be Voluntary

All ethical research must be conducted using willing participants. Study volunteers should not feel coerced, threatened or bribed into participation. This becomes especially important for researchers working at universities or prisons, where students and inmates are often encouraged to participate in experiments.

Researchers Must Obtain Informed Consent

Informed consent is a procedure in which all study participants are told about procedures and informed of any potential risks. Consent should be documented in written form. Informed consent ensures that participants know enough about the experiment to make an informed decision about whether or not they want to participate.

Obviously, this can present problems in cases where telling the participants the necessary details about the experiment might unduly influence their responses or behaviors in the study. The use of deception in psychology research is allowed in certain instances, but only if the study would be impossible to conduct without the use of deception, if the research will provide some sort of valuable insight and if the subjects will be debriefed and informed about the study's true purpose after the data has been collected.

Researchers Must Maintain Participant Confidentiality

Confidentiality is an essential part of any ethical psychology research. Participants need to be guaranteed that identifying information and individual responses will not be shared with anyone who is not involved in the study.

While these guidelines provide some ethical standards for research, each study is different and may present unique challenges. Because of this, most colleges and universities have a Human Subjects Committee or Institutional Review Board that oversees and grants approval for any research conducted by faculty members or students. These committees provide an important safeguard to ensure academic research is ethical and does not pose a risk to study participants.

American Psychological Association. Ethical principles of psychologists and code of conduct .

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

How the Classics Changed Research Ethics

Some of history’s most controversial psychology studies helped drive extensive protections for human research participants. some say those reforms went too far..

- Behavioral Research

- Institutional Review Board (IRB)

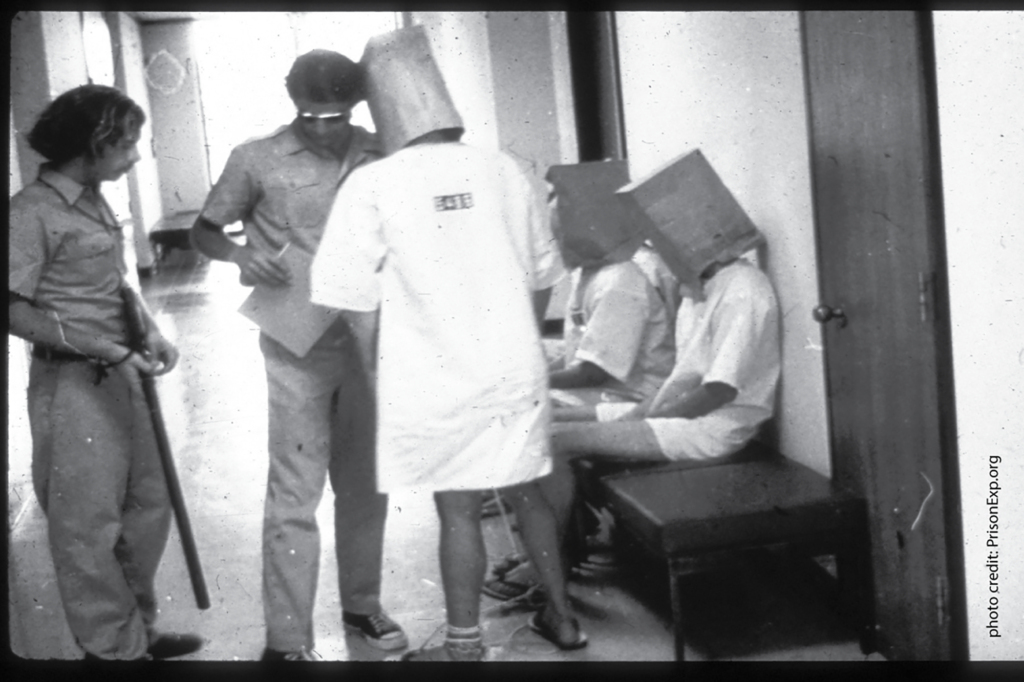

Photo above: In 1971, APS Fellow Philip Zimbardo halted his classic prison simulation at Stanford after volunteer “guards” became abusive to the “prisoners,” famously leading one prisoner into a fit of sobbing. Photo credit: PrisonExp.org

Nearly 60 years have passed since Stanley Milgram’s infamous “shock box” study sparked an international focus on ethics in psychological research. Countless historians and psychology instructors assert that Milgram’s experiments—along with studies like the Robbers Cave and Stanford prison experiments—could never occur today; ethics gatekeepers would swiftly bar such studies from proceeding, recognizing the potential harms to the participants.

But the reforms that followed some of the 20th century’s most alarming biomedical and behavioral studies have overreached, many social and behavioral scientists complain. Studies that pose no peril to participants confront the same standards as experimental drug treatments or surgeries, they contend. The institutional review boards (IRBs) charged with protecting research participants fail to understand minimal risk, they say. Researchers complain they waste time addressing IRB concerns that have nothing to do with participant safety.

Several factors contribute to this conflict, ethicists say. Researchers and IRBs operate in a climate of misunderstanding, confusing regulations, and a systemic lack of ethics training, said APS Fellow Celia Fisher, a Fordham University professor and research ethicist, in an interview with the Observer .

“In my view, IRBs are trying to do their best and investigators are trying to do their best,” Fisher said. “It’s more that we really have to enhance communication and training on both sides.”

‘Sins’ from the past

Modern human-subjects protections date back to the 1947 Nuremberg Code, the response to Nazi medical experiments on concentration-camp internees. Those ethical principles, which no nation or organization has officially accepted as law or official ethics guidelines, emphasized that a study’s benefits should outweigh the risks and that human subjects should be fully informed about the research and participate voluntarily.

See the 2014 Observer cover story by APS Fellow Carol A. Tavris, “ Teaching Contentious Classics ,” for more about these controversial studies and how to discuss them with students.

But the discovery of U.S.-government-sponsored research abuses, including the Tuskegee syphilis experiment on African American men and radiation experiments on humans, accelerated regulatory initiatives. The abuses investigators uncovered in the 1970s, 80s, and 90s—decades after the experiments had occurred—heightened policymakers’ concerns “about what else might still be going on,” George Mason University historian Zachary M. Schrag explained in an interview. These concerns generated restrictions not only on biomedical research but on social and behavioral studies that pose a minute risk of harm.

“The sins of researchers from the 1940s led to new regulations in the 1990s, even though it was not at all clear that those kinds of activities were still going on in any way,” said Schrag, who chronicled the rise of IRBs in his book Ethical Imperialism: Institutional Review Boards and the Social Sciences, 1965–2009.

Accompanying the medical research scandals were controversial psychological studies that provided fodder for textbooks, historical tomes, and movies.

- In the early 1950s, social psychologist Muzafer Sherif and his colleagues used a Boy Scout camp called Robbers Cave to study intergroup hostility. They randomly assigned preadolescent boys to one of two groups and concocted a series of competitive activities that quickly sparked conflict. They later set up a situation that compelled the boys to overcome their differences and work together. The study provided insights into prejudice and conflict resolution but generated criticism because the children weren’t told they were part of an experiment.

- In 1961, Milgram began his studies on obedience to authority by directing participants to administer increasing levels of electric shock to another person (a confederate). To Milgram’s surprise, more than 65% of the participants delivered the full voltage of shock (which unbeknownst to them was fake), even though many were distressed about doing so. Milgram was widely criticized for the manipulation and deception he employed to carry out his experiments.

- In 1971, APS Fellow Philip Zimbardo halted his classic prison simulation at Stanford after volunteer “guards” became abusive to the “prisoners,” famously leading one prisoner into a fit of sobbing.

Western policymakers created a variety of safeguards in the wake of these psychological studies and other medical research. Among them was the Declaration of Helsinki, an ethical guide for human-subjects research developed by the Europe-based World Medical Association. The U.S. Congress passed the National Research Act of 1974, which created a commission to oversee participant protections in biomedical and behavioral research. And in the 90s, federal agencies adopted the Federal Policy for the Protection of Human Subjects (better known as the Common Rule), a code of ethics applied to any government-funded research. IRBs review studies through the lens of the Common Rule. After that, social science research, including studies in social psychology, anthropology, sociology, and political science, began facing widespread institutional review (Schrag, 2010).

Sailing Through Review

Psychological scientists and other researchers who have served on institutional review boards provide these tips to help researchers get their studies reviewed swiftly.

- Determine whether your study qualifies for minimal-risk exemption from review. Online tools are even in development to help researchers self-determine exempt status (Ben-Shahar, 2019; Schneider & McClutcheon, 2018).

- If you’re not clear about your exemption, research the regulations to understand how they apply to your planned study. Show you’ve done your homework and have developed a protocol that is safe for your participants.

- Consult with stakeholders. Look for advocacy groups and representatives from the population you plan to study. Ask them what they regard as fair compensation for participation. Get their feedback about your questionnaires and consent forms to make sure they’re understandable. These steps help you better show your IRB that the population you’re studying will find the protections adequate (Fisher, 2022).

- Speak to IRB members or staff before submitting the protocol. Ask them their specific concerns about your study, and get guidance on writing up the protocol to address those concerns. Also ask them about expected turnaround times so you can plan your submission in time to meet any deadlines associated with your study (e.g., grant application deadlines).

Ben-Shahar, O. (2019, December 2). Reforming the IRB in experimental fashion. The Regulatory Review . University of Pennsylvania. https://www.theregreview.org/2019/12/02/ben-shahar-reforming-irb-experimental-fashion/

Fisher, C. B. (2022). Decoding the ethics code: A practical guide for psychologists (5 th ed.). Sage Publications.

Schneider, S. L. & McCutcheon, J. A. (2018). Proof of concept: Use of a wizard for self-determination of IRB exempt status . Federal Demonstration Partnership. http://thefdp.org/default/assets/File/Documents/wizard_pilot_final_rpt.pdf

Social scientists have long contended that the Common Rule was largely designed to protect participants in biomedical experiments—where scientists face the risk of inducing physical harm on subjects—but fits poorly with the other disciplines that fall within its reach.

“It’s not like the IRBs are trying to hinder research. It’s just that regulations continue to be written in the medical model without any specificity for social science research,” she explained.

The Common Rule was updated in 2018 to ease the level of institutional review for low-risk research techniques (e.g., surveys, educational tests, interviews) that are frequent tools in social and behavioral studies. A special committee of the National Research Council (NRC), chaired by APS Past President Susan Fiske, recommended many of those modifications. Fisher was involved in the NRC committee, along with APS Fellows Richard Nisbett (University of Michigan) and Felice J. Levine (American Educational Research Association), and clinical psychologist Melissa Abraham of Harvard University. But the Common Rule reforms have yet to fully expedite much of the research, partly because the review boards remain confused about exempt categories, Fisher said.

Interference or support?

That regulatory confusion has generated sour sentiments toward IRBs. For decades, many social and behavioral scientists have complained that IRBs effectively impede scientific progress through arbitrary questions and objections.

In a Perspectives on Psychological Science paper they co-authored, APS Fellows Stephen Ceci of Cornell University and Maggie Bruck of Johns Hopkins University discussed an IRB rejection of their plans for a study with 6- to 10-year-old participants. Ceci and Bruck planned to show the children videos depicting a fictional police officer engaging in suggestive questioning of a child.

“The IRB refused to approve the proposal because it was deemed unethical to show children public servants in a negative light,” they wrote, adding that the IRB held firm on its rejection despite government funders already having approved the study protocol (Ceci & Bruck, 2009).

Other scientists have complained the IRBs exceed their Common Rule authority by requiring review of studies that are not government funded. In 2011, psychological scientist Jin Li sued Brown University in federal court for barring her from using data she collected in a privately funded study on educational testing. Brown’s IRB objected to the fact that she paid her participants different amounts of compensation based on need. (A year later, the university settled the case with Li.)

In addition, IRBs often hover over minor aspects of a study that have no genuine relation to participant welfare, Ceci said in an email interview.

“You can have IRB approval and later decide to make a nominal change to the protocol (a frequent one is to add a new assistant to the project or to increase the sample size),” he wrote. “It can take over a month to get approval. In the meantime, nothing can move forward and the students sit around waiting.”

Not all researchers view institutional review as a roadblock. Psychological scientist Nathaniel Herr, who runs American University’s Interpersonal Emotion Lab and has served on the school’s IRB, says the board effectively collaborated with researchers to ensure the study designs were safe and that participant privacy was appropriately protected

“If the IRB that I operated on saw an issue, they shared suggestions we could make to overcome that issue,” Herr said. “It was about making the research go forward. I never saw a project get shut down. It might have required a significant change, but it was often about confidentiality and it’s something that helps everybody feel better about the fact we weren’t abusing our privilege as researchers. I really believe it [the review process] makes the projects better.”

Some universities—including Fordham University, Yale University, and The University of Chicago—even have social and behavioral research IRBs whose members include experts optimally equipped to judge the safety of a psychological study, Fisher noted.

Training gaps

Institutional review is beset by a lack of ethics training in research programs, Fisher believes. While students in professional psychology programs take accreditation-required ethics courses in their doctoral programs, psychologists in other fields have no such requirement. In these programs, ethics training is often limited to an online program that provides, at best, a perfunctory overview of federal regulations.

“It gives you the fundamental information, but it has nothing to do with our real-world deliberations about protecting participants,” she said.

Additionally, harm to a participant is difficult to predict. As sociologist Martin Tolich of University of Otago in New Zealand wrote, the Stanford prison study had been IRB-approved.

“Prediction of harm with any certainty is not necessarily possible, and should not be the aim of ethics review,” he argued. “A more measured goal is the minimization of risk, not its eradication” (Tolich, 2014).

Fisher notes that scientists aren’t trained to recognize and respond to adverse events when they occur during a study.

“To be trained in research ethics requires not just knowing you have to obtain informed consent,” she said. “It’s being able to apply ethical reasoning to each unique situation. If you don’t have the training to do that, then of course you’re just following the IRB rules, which are very impersonal and really out of sync with the true nature of what we’re doing.”

Researchers also raise concerns that, in many cases, the regulatory process harms vulnerable populations rather than safeguards them. Fisher and psychological scientist Brian Mustanski of University of Illinois at Chicago wrote in 2016, for example, that the review panels may be hindering HIV prevention strategies by requiring researchers to get parental consent before including gay and bisexual adolescents in their studies. Under that requirement, youth who are not out to their families get excluded. Boards apply those restrictions even in states permitting minors to get HIV testing and preventive medication without parental permission—and even though federal rules allow IRBs to waive parental consent in research settings (Mustanski & Fisher, 2016)

IRBs also place counterproductive safety limits on suicide and self-harm research, watching for any sign that a participant might need to be removed from a clinical study and hospitalized.

“The problem is we know that hospitalization is not the panacea,” Fisher said. “It stops suicidality for the moment, but actually the highest-risk period is 3 months after the first hospitalization for a suicide attempt. Some of the IRBs fail to consider that a non-hospitalization intervention that’s being tested is just as safe as hospitalization. It’s a difficult problem, and I don’t blame them. But if we have to take people out of a study as soon as they reach a certain level of suicidality, then we’ll never find effective treatment.”

Communication gaps

Supporters of the institutional review process say researchers tend to approach the IRB process too defensively, overlooking the board’s good intentions.

“Obtaining clarification or requesting further materials serve to verify that protections are in place,” a team of institutional reviewers wrote in an editorial for Psi Chi Journal of Psychological Research . “If researchers assume that IRBs are collaborators in the research process, then these requests can be seen as prompts rather than as admonitions” (Domenech Rodriguez et al., 2017).

Fisher agrees that researchers’ attitudes play a considerable role in the conflicts that arise over ethics review. She recommends researchers develop each protocol with review-board questions in mind (see sidebar).

“For many researchers, there’s a disdain for IRBs,” she said. “IRBs are trying their hardest. They don’t want to reject research. It’s just that they’re not informed. And sometimes if behavioral scientists or social scientists are disdainful of their IRBs, they’re not communicating with them.”

Some researchers are building evidence to help IRBs understand the level of risk associated with certain types of psychological studies.

- In a study involving more than 500 undergraduate students, for example, psychological scientists at the University of New Mexico found that the participants were less upset than expected by questionnaires about sex, trauma , and other sensitive topics. This finding, the researchers reported in Psychological Science , challenges the usual IRB assumption about the stress that surveys on sex and trauma might inflict on participants (Yeater et al., 2012).

- A study involving undergraduate women indicated that participants who had experienced child abuse , although more likely than their peers to report distress from recalling the past as part of a study, were also more likely to say that their involvement in the research helped them gain insight into themselves and hoped it would help others (Decker et al., 2011).

- A multidisciplinary team, including APS Fellow R. Michael Furr of Wake Forest University, found that adolescent psychiatric patients showed a drop in suicide ideation after being questioned regularly about their suicidal thoughts over the course of 2 years. This countered concerns that asking about suicidal ideation would trigger an increase in such thinking (Mathias et al., 2012).

- A meta-analysis of more than 70 participant samples—totaling nearly 74,000 individuals—indicated that people may experience only moderate distress when discussing past traumas in research studies. They also generally might find their participation to be a positive experience, according to the findings (Jaffe et al., 2015).

The takeaways

So, are the historians correct? Would any of these classic experiments survive IRB scrutiny today?

Reexaminations of those studies make the question arguably moot. Recent revelations about some of these studies suggest that scientific integrity concerns may taint the legacy of those findings as much as their impact on participants did (Le Texier, 2019, Resnick, 2018; Perry, 2018).

Also, not every aspect of the controversial classics is taboo in today’s regulatory environment. Scientists have won IRB approval to conceptually replicate both the Milgram and Stanford prison experiments (Burger, 2009; Reicher & Haslam, 2006). They simply modified the protocols to avert any potential harm to the participants. (Scholars, including Zimbardo himself, have questioned the robustness of those replication findings [Elms, 2009; Miller, 2009; Zimbardo, 2006].)

Many scholars believe there are clear and valuable lessons from the classic experiments. Milgram’s work, for instance, can inject clarity into pressing societal issues such as political polarization and police brutality . Ethics training and monitoring simply need to include those lessons learned, they say.

“We should absolutely be talking about what Milgram did right, what he did wrong,” Schrag said. “We can talk about what we can learn from that experience and how we might answer important questions while respecting the rights of volunteers who participate in psychological experiments.”

Feedback on this article? Email [email protected] or login to comment.

References

Burger, J. M. (2009). Replicating Milgram: Would people still obey today? American Psychologist , 64 (1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0010932

Ceci, S. J. & Bruck, M. (2009). Do IRBs pass the minimal harm test? Perspectives on Psychological Science , 4 (1), 28–29. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6924.2009.01084.x

Decker, S. E., Naugle, A. E., Carter-Visscher, R., Bell, K., & Seifer, A. (2011). Ethical issues in research on sensitive topics: Participants’ experiences of stress and benefit . Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics: An International Journal , 6 (3), 55–64. https://doi.org/10.1525/jer.2011.6.3.55

Domenech Rodriguez, M. M., Corralejo, S. M., Vouvalis, N., & Mirly, A. K. (2017). Institutional review board: Ally not adversary. Psi Chi Journal of Psychological Research , 22 (2), 76–84. https://doi.org/10.24839/2325-7342.JN22.2.76

Elms, A. C. (2009). Obedience lite. American Psychologist , 64 (1), 32–36. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014473

Fisher, C. B., True, G., Alexander, L., & Fried, A. L. (2009). Measures of mentoring, department climate, and graduate student preparedness in the responsible conduct of psychological research. Ethics & Behavior , 19 (3), 227–252. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508420902886726

Jaffe, A. E., DiLillo, D., Hoffman, L., Haikalis, M., & Dykstra, R. E. (2015). Does it hurt to ask? A meta-analysis of participant reactions to trauma research. Clinical Psychology Review , 40 , 40–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2015.05.004

Le Texier, T. (2019). Debunking the Stanford Prison experiment. American Psychologist , 74 (7), 823–839. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/amp0000401

Mathias, C. W., Furr, R. M., Sheftall, A. H., Hill-Kapturczak, N., Crum, P., & Dougherty, D. M. (2012). What’s the harm in asking about suicide ideation? Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior , 42 (3), 341–351. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1943-278X.2012.0095.x

Miller, A. G. (2009). Reflections on “Replicating Milgram” (Burger, 2009). American Psychologist , 64 (1), 20–27. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014407

Mustanski, B., & Fisher, C. B. (2016). HIV rates are increasing in gay/bisexual teens: IRB barriers to research must be resolved to bend the curve. American Journal of Preventive Medicine , 51 (2), 249–252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2016.02.026

Perry, G. (2018). The lost boys: Inside Muzafer Sherif’s Robbers Cave experiment. Scribe Publications.

Reicher, S. & Haslam, S. A. (2006). Rethinking the psychology of tyranny: The BBC prison study. British Journal of Social Psychology , 45 , 1–40. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466605X48998

Resnick, B. (2018, June 13). The Stanford prison experiment was massively influential. We just learned it was a fraud. Vox. https://www.vox.com/2018/6/13/17449118/stanford-prison-experiment-fraud-psychology-replication

Schrag, Z. M. (2010). Ethical imperialism: Institutional review boards and the social sciences, 1965–2009 . Johns Hopkins University Press.

Tolich, M. (2014). What can Milgram and Zimbardo teach ethics committees and qualitative researchers about minimal harm? Research Ethics , 10 (2), 86–96. https://doi.org/10.1177/1747016114523771

Yeater, E., Miller, G., Rinehart, J., & Nason, E. (2012). Trauma and sex surveys meet minimal risk standards: Implications for institutional review boards. Psychological Science , 23 (7), 780–787. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797611435131

Zimbardo, P. G. (2006). On rethinking the psychology of tyranny: The BBC prison study. British Journal of Social Psychology , 45 , 47–53. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466605X81720

APS regularly opens certain online articles for discussion on our website. Effective February 2021, you must be a logged-in APS member to post comments. By posting a comment, you agree to our Community Guidelines and the display of your profile information, including your name and affiliation. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations present in article comments are those of the writers and do not necessarily reflect the views of APS or the article’s author. For more information, please see our Community Guidelines .

Please login with your APS account to comment.

About the Author

Scott Sleek is a freelance writer in Silver Spring, Maryland, and the former director of news and information at APS.

Inside Grants: National Science Foundation Research Data Ecosystems (RDE)

The National Science Foundation’s Research Data Ecosystems (RDE) is a $38 million effort to improve scientific research through modernized data management collection.

Up-and-Coming Voices: Methodology and Research Practices

Talks by students and early-career researchers related to methodology and research practices.

Understanding ‘Scientific Consensus’ May Correct Misperceptions About GMOs, but Not Climate Change

Explaining the meaning of “scientific consensus” may be more effective at countering some types of misinformation than others.

Privacy Overview

https://www.simplypsychology.org/Ethics.html

McLeod, S. \(2015\). Psychology research ethics. Simply Psychology. Retrieved from https://www.simplypsychology.org/Ethics.html.

CITE AS:

McLeod, S. \(2015\). Psychology research ethics. Simply Psychology. https://www.simplypsychology.org/Ethics.html.

- Subject List

- Take a Tour

- For Authors

- Subscriber Services

- Publications

- African American Studies

- African Studies

- American Literature

- Anthropology

- Architecture Planning and Preservation

- Art History

- Atlantic History

- Biblical Studies

- British and Irish Literature

- Childhood Studies

- Chinese Studies

- Cinema and Media Studies

- Communication

- Criminology

- Environmental Science

- Evolutionary Biology

- International Law

- International Relations

- Islamic Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Latino Studies

- Linguistics

- Literary and Critical Theory

- Medieval Studies

- Military History

- Political Science

- Public Health

- Renaissance and Reformation

- Social Work

- Urban Studies

- Victorian Literature

- Browse All Subjects

How to Subscribe

- Free Trials

In This Article Expand or collapse the "in this article" section Ethics in Psychological Practice

Introduction, general overviews.

- Nonrational Factors in Ethical Decision Making

- Scientifically and Professionally Informed Competence

- Emotional Competence

- Risk Management and Boundaries

- Sexual Boundaries

- Boundaries and Technology

- Confidentiality and Record Keeping

- Patients Who Threaten to Harm Others

- Patients Who Threaten to Harm Themselves

- Forensic Psychology

- Informed Consent

- Other Special Topics

- Risk Management (Quality Enhancement)

- Ethics Education and Supervision

Related Articles Expand or collapse the "related articles" section about

About related articles close popup.

Lorem Ipsum Sit Dolor Amet

Vestibulum ante ipsum primis in faucibus orci luctus et ultrices posuere cubilia Curae; Aliquam ligula odio, euismod ut aliquam et, vestibulum nec risus. Nulla viverra, arcu et iaculis consequat, justo diam ornare tellus, semper ultrices tellus nunc eu tellus.

- Abnormal Psychology

- Clinical Psychology

- Counseling Psychology

- Counseling Services in School Psychology

- Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM)

Other Subject Areas

Forthcoming articles expand or collapse the "forthcoming articles" section.

- Data Visualization

- Executive Functions in Childhood

- Remote Work

- Find more forthcoming articles...

- Export Citations

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Ethics in Psychological Practice by Samuel Knapp , Leon VandeCreek LAST REVIEWED: 30 September 2013 LAST MODIFIED: 30 September 2013 DOI: 10.1093/obo/9780199828340-0024

Professional ethics refers to the laws, regulations, and standards that govern the profession (including ethics codes), the overarching ethical principles that underlie enforceable standards of conduct, ethical decision-making skills, risk management strategies, and self-regulation (emotional competence). The rules and guidelines for professional conduct are codified in the ethics code of the profession; in psychology this code is titled Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct (American Psychological Association [APA], 2010; hereafter Ethics Code). However, laws and standards cannot address all of the issues that professional psychologists face. Psychologists encounter situations that are too unique or context dependent to be covered in law or in an ethics code. Also, psychologists may encounter situations unanticipated by the ethics code, or they may encounter situations in which overarching ethical principles appear to collide with the law or the policies of an institution that employs them. Consequently, psychologists need to rely on overarching ethical values and engage in decision making. “Risk management” refers to activities that reduce the likelihood that psychologists will be investigated or convicted by a disciplinary body. To recent scholars, risk management strategies should focus on implementing or fulfilling overarching ethical principles. This perspective on allowing overarching ethical principles to guide professional behavior is called “positive ethics.”

These are some of the more referenced textbooks and overviews of ethics for professional psychologists. Each has its own strengths and unique features. Most are developed for graduate students in psychology or related fields. Fisher 2013 focuses primarily on the ethics code itself, whereas Knapp and VandeCreek 2012 , Koocher and Keith-Spiegel 2008 , Pope and Vasquez 2011 , and Kitchener and Anderson 2011 deal with ethics in a broader sense. Bersoff 2008 is an edited text with substantial commentary by the author. Anderson and Handelsman 2010 focuses more on self-reflection and less on factual content.

Anderson, S., and M. M. Handelsman. 2010. Ethics for psychotherapists and counselors: A proactive approach . Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

Relying heavily on the ethics acculturation model and the use of an ethics autobiography, Anderson and Handelsman provide a series of exercises and discussions designed to socialize young professionals into the profession.

Bersoff, D., ed. 2008. Ethical conflicts in psychology . 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

This text contains excerpts from some of the more salient articles in professional psychology accompanied by commentary.

Fisher, C. 2013 . Decoding the ethics code: A practical guide for psychologists . 3d ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

Fisher, who was the chair of the committee that recommended changes in the 2002 Ethics Code, clearly explains the principles of the APA Ethics Code, gives useful illustrations, and identifies the rationale behind many of the standards and how they fit into the overall obligations of psychologists. However, the text limits its scope to the Ethics Code and does not consider other areas of ethics such as decision-making models or risk management strategies.

Kitchener, K. S., and S. Anderson. 2011. Foundations of ethical practice, research and teaching in psychology and counseling . New York: Routledge.

The unique strength is its detailed coverage of overarching ethical theories, including the decision-making model proposed.

Knapp, S., and L. VandeCreek. 2012. Practical ethics for psychologists: A positive approach . 2d ed. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Knapp and VandeCreek emphasize positive ethics, or the idea that ethics should focus on more than simply avoiding disciplinary action but should be anchored in an overarching ethical theory that guides a wide range of professional behaviors.

Koocher, G., and P. Keith-Spiegel. 2008. Ethics in psychology and the mental health professions: Standards and cases . 3d ed. New York: Oxford Univ. Press.

This is a classic, with clear coverage of essential issues and entertaining vignettes that illustrate important points.

Pope, K. S., and M. Vasquez. 2011 . Ethics in psychotherapy and counseling: A practical guide . 4th ed. New York: Wiley.

This is a good, practical textbook that emphasizes self-management and self-awareness more than other texts.

back to top

Users without a subscription are not able to see the full content on this page. Please subscribe or login .

Oxford Bibliographies Online is available by subscription and perpetual access to institutions. For more information or to contact an Oxford Sales Representative click here .

- About Psychology »

- Meet the Editorial Board »

- Academic Assessment

- Acculturation and Health

- Action Regulation Theory

- Action Research

- Addictive Behavior

- Adolescence

- Adoption, Social, Psychological, and Evolutionary Perspect...

- Advanced Theory of Mind

- Affective Forecasting

- Affirmative Action

- Ageism at Work

- Allport, Gordon

- Alzheimer’s Disease

- Ambulatory Assessment in Behavioral Science

- Analysis of Covariance (ANCOVA)

- Animal Behavior

- Animal Learning

- Anxiety Disorders

- Art and Aesthetics, Psychology of

- Artificial Intelligence, Machine Learning, and Psychology

- Assessment and Clinical Applications of Individual Differe...

- Attachment in Social and Emotional Development across the ...

- Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in Adults

- Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in Childre...

- Attitudinal Ambivalence

- Attraction in Close Relationships

- Attribution Theory

- Authoritarian Personality

- Bayesian Statistical Methods in Psychology

- Behavior Therapy, Rational Emotive

- Behavioral Economics

- Behavioral Genetics

- Belief Perseverance

- Bereavement and Grief

- Biological Psychology

- Birth Order

- Body Image in Men and Women

- Bystander Effect

- Categorical Data Analysis in Psychology

- Childhood and Adolescence, Peer Victimization and Bullying...

- Clark, Mamie Phipps

- Clinical Neuropsychology

- Cognitive Consistency Theories

- Cognitive Dissonance Theory

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Communication, Nonverbal Cues and

- Comparative Psychology

- Competence to Stand Trial: Restoration Services

- Competency to Stand Trial

- Computational Psychology

- Conflict Management in the Workplace

- Conformity, Compliance, and Obedience

- Consciousness

- Coping Processes

- Correspondence Analysis in Psychology

- Creativity at Work

- Critical Thinking

- Cross-Cultural Psychology

- Cultural Psychology

- Daily Life, Research Methods for Studying

- Data Science Methods for Psychology

- Data Sharing in Psychology

- Death and Dying

- Deceiving and Detecting Deceit

- Defensive Processes

- Depressive Disorders

- Development, Prenatal

- Developmental Psychology (Cognitive)

- Developmental Psychology (Social)

- Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM...

- Discrimination

- Dissociative Disorders

- Drugs and Behavior

- Eating Disorders

- Ecological Psychology

- Educational Settings, Assessment of Thinking in

- Effect Size

- Embodiment and Embodied Cognition

- Emerging Adulthood

- Emotional Intelligence

- Empathy and Altruism

- Employee Stress and Well-Being

- Environmental Neuroscience and Environmental Psychology

- Ethics in Psychological Practice

- Event Perception

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Expansive Posture

- Experimental Existential Psychology

- Exploratory Data Analysis

- Eyewitness Testimony

- Eysenck, Hans

- Factor Analysis

- Festinger, Leon

- Five-Factor Model of Personality

- Flynn Effect, The

- Forgiveness

- Friendships, Children's

- Fundamental Attribution Error/Correspondence Bias

- Gambler's Fallacy

- Game Theory and Psychology

- Geropsychology, Clinical

- Global Mental Health

- Habit Formation and Behavior Change

- Health Psychology

- Health Psychology Research and Practice, Measurement in

- Heider, Fritz

- Heuristics and Biases

- History of Psychology

- Human Factors

- Humanistic Psychology

- Implicit Association Test (IAT)

- Industrial and Organizational Psychology

- Inferential Statistics in Psychology

- Insanity Defense, The

- Intelligence

- Intelligence, Crystallized and Fluid

- Intercultural Psychology

- Intergroup Conflict

- International Classification of Diseases and Related Healt...

- International Psychology

- Interviewing in Forensic Settings

- Intimate Partner Violence, Psychological Perspectives on

- Introversion–Extraversion

- Item Response Theory

- Law, Psychology and

- Lazarus, Richard

- Learned Helplessness

- Learning Theory

- Learning versus Performance

- LGBTQ+ Romantic Relationships

- Lie Detection in a Forensic Context

- Life-Span Development

- Locus of Control

- Loneliness and Health

- Mathematical Psychology

- Meaning in Life

- Mechanisms and Processes of Peer Contagion

- Media Violence, Psychological Perspectives on

- Mediation Analysis

- Memories, Autobiographical

- Memories, Flashbulb

- Memories, Repressed and Recovered

- Memory, False

- Memory, Human

- Memory, Implicit versus Explicit

- Memory in Educational Settings

- Memory, Semantic

- Meta-Analysis

- Metacognition

- Metaphor, Psychological Perspectives on

- Microaggressions

- Military Psychology

- Mindfulness

- Mindfulness and Education

- Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI)

- Money, Psychology of

- Moral Conviction

- Moral Development

- Moral Psychology

- Moral Reasoning

- Nature versus Nurture Debate in Psychology

- Neuroscience of Associative Learning

- Nonergodicity in Psychology and Neuroscience

- Nonparametric Statistical Analysis in Psychology

- Observational (Non-Randomized) Studies

- Obsessive-Complusive Disorder (OCD)

- Occupational Health Psychology

- Olfaction, Human

- Operant Conditioning

- Optimism and Pessimism

- Organizational Justice

- Parenting Stress

- Parenting Styles

- Parents' Beliefs about Children

- Path Models

- Peace Psychology

- Perception, Person

- Performance Appraisal

- Personality and Health

- Personality Disorders

- Personality Psychology

- Person-Centered and Experiential Psychotherapies: From Car...

- Phenomenological Psychology

- Placebo Effects in Psychology

- Play Behavior

- Positive Psychological Capital (PsyCap)

- Positive Psychology

- Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)

- Prejudice and Stereotyping

- Pretrial Publicity

- Prisoner's Dilemma

- Problem Solving and Decision Making

- Procrastination

- Prosocial Behavior

- Prosocial Spending and Well-Being

- Protocol Analysis

- Psycholinguistics

- Psychological Literacy

- Psychological Perspectives on Food and Eating

- Psychology, Political

- Psychoneuroimmunology

- Psychophysics, Visual

- Psychotherapy

- Psychotic Disorders

- Publication Bias in Psychology

- Reasoning, Counterfactual

- Rehabilitation Psychology

- Relationships

- Reliability–Contemporary Psychometric Conceptions

- Religion, Psychology and

- Replication Initiatives in Psychology

- Research Methods

- Risk Taking

- Role of the Expert Witness in Forensic Psychology, The

- Sample Size Planning for Statistical Power and Accurate Es...

- Schizophrenic Disorders

- School Psychology

- School Psychology, Counseling Services in

- Self, Gender and

- Self, Psychology of the

- Self-Construal

- Self-Control

- Self-Deception

- Self-Determination Theory

- Self-Efficacy

- Self-Esteem

- Self-Monitoring

- Self-Regulation in Educational Settings

- Self-Report Tests, Measures, and Inventories in Clinical P...

- Sensation Seeking

- Sex and Gender

- Sexual Minority Parenting

- Sexual Orientation

- Signal Detection Theory and its Applications

- Simpson's Paradox in Psychology

- Single People

- Single-Case Experimental Designs

- Skinner, B.F.

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Small Groups

- Social Class and Social Status

- Social Cognition

- Social Neuroscience

- Social Support

- Social Touch and Massage Therapy Research

- Somatoform Disorders

- Spatial Attention

- Sports Psychology

- Stanford Prison Experiment (SPE): Icon and Controversy

- Stereotype Threat

- Stereotypes

- Stress and Coping, Psychology of

- Student Success in College

- Subjective Wellbeing Homeostasis

- Taste, Psychological Perspectives on

- Teaching of Psychology

- Terror Management Theory

- Testing and Assessment

- The Concept of Validity in Psychological Assessment

- The Neuroscience of Emotion Regulation

- The Reasoned Action Approach and the Theories of Reasoned ...

- The Weapon Focus Effect in Eyewitness Memory

- Theory of Mind

- Therapy, Cognitive-Behavioral

- Thinking Skills in Educational Settings

- Time Perception

- Trait Perspective

- Trauma Psychology

- Twin Studies

- Type A Behavior Pattern (Coronary Prone Personality)

- Unconscious Processes

- Video Games and Violent Content

- Virtues and Character Strengths

- Women and Science, Technology, Engineering, and Math (STEM...

- Women, Psychology of

- Work Well-Being

- Workforce Training Evaluation

- Wundt, Wilhelm

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Legal Notice

- Accessibility

Powered by:

- [66.249.64.20|81.177.182.174]

- 81.177.182.174

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

4 The Essence of Ethics for Psychological Researchers and Psychologists

Tanya Machin and Charlotte Brownlow

This chapter uses material from an open access human research ethics e-course developed with the support of an Open Access Teaching Award from the University of Southern Queensland. The original authors were Tanya Machin, Charlotte Brownlow, and Annmaree Jackson. The e-course can be found at https://open.usq.edu.au/course/view.php?id=400 or by directly contacting Tanya at [email protected] or Charlotte at [email protected] .

Introduction

Our aim in this chapter is to provide you with a broad overview of the different ethical codes used in Australia that psychological scientists and psychologists use to guide their work. As a psychology student you’re no doubt used to thinking about ethics as this underpins much of the foundational knowledge you learn in your degree. However, you may be unfamiliar with why ethics are important (although we hope not!) or when or how ethical codes are used. The first ethical code was developed by the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC) and is known as The National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research (NHMRC, 2018b) or the ‘NHMRC code’ or simply ‘the code’. This document consists of a series of guidelines that all researchers – including psychological scientists – need to follow. Australia is unique in that our researchers are governed by this code, but our psychologists are required to adhere to a different ethical code developed by the Australian Psychological Society. Countries such as the United Kingdom or Canada have a combined professional and research code of ethics.

To help you work your way through the chapter, we’ve divided it into several sections, including: ‘Why Do We Have Research Ethics?’, ‘Research Methodology and Risk Management’, ‘Recruitment and Data Collection’, ‘Data and Information Management’, and ‘Merit, Integrity, and Monitoring’. We will then provide a brief overview of the APS code to close the chapter off. Throughout the chapter, we’ll provide some case studies, pose questions for you to reflect on, and perhaps even test your ethical knowledge! Finally, the information contained in this chapter comes from an open access e-course that we wrote. If you have any questions about the e-course or want to use it in your course or program, please contact the authors directly.

Why do we have research ethics?

The history of human experimentation is sometimes considered to be a dark one, with many documented examples of ill-conceived and inhumane medical and psychological experimentation on human beings. While considered ‘unethical’ by today’s standards, these experiments have led to the development and refinement of various national and international laws and guidelines that govern ethical human research.

Case Study: The Tuskegee Syphilis Study

In 1932, the United States of America Public Health Service (PHS) began a twelve-month experiment in Tuskegee, Alabama to study the natural course of untreated syphilis in African American men. The research aimed to determine whether syphilis caused cardiovascular disease more often than neurological damage and to determine if the course of syphilis was different between black and white men. When the study began, there was no known cure for syphilis.

From an ethical perspective, this research provides an excellent case study on how NOT to conduct research responsibly. Researchers initially recruited 600 men: 399 with syphilis and 201 who did not have syphilis. Poor, uneducated African American men were targeted for participation (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] (2021)). As an ‘incentive’ to join research, free medical exams, meals, and burial insurance were offered. The PHS never told the participants they were part of a syphilis study – some men thoughts they were being treated for rheumatism or bad stomachs (Brown, 2017). When penicillin became available as the recommended treatment in 1945, the treatment was withheld from participants (Tuskegee University, n.d). The study was initially supposed to be conducted over a six-month period, however, the study ran for 40 years without subsequent ethical review despite the introduction of numerous international ethical guideline documents.

When Dr John Heller, Director of the PHS Venereal Diseases Unit (1943 to 1948), was interviewed about the research project in 1976, he reflected that the men were considered purely as subjects in a study rather than patients who were in need of treatment.

What Did We Learn?

By today’s standards, this research would not be approved by an ethical review body on the basis of:

- lack of voluntary and informed consent processes

- inappropriate use of deception in various stages of research conduct

- use of inappropriate incentives and payments that have likely induced and encouraged the participants to take risks by participating in the research

- withholding known treatments that would benefit the participant once available

- knowingly permitting transmission of the disease to other non-participant individuals (e.g., wives and children of the participant men)

- lack of reporting and monitoring processes.

Video 4.1 provides a 10-minute summary of the Tuskagee Study.

Video 4.1: The Tuskegee Syphilis Study

Governance of Human Research

Today research involving humans is tightly governed. Governance of human research is about establishing both rights for participants in research and the responsibilities of those conducting the research (that’s you as a researcher and your research institution). This can include:

- ethical review and approval

- compliance with legislation, regulations, guidelines and codes of practice

- legal matters – including contracts – and indemnity/insurance frameworks

- financial management, risk management, and site-specific assessment

- institutional policies and procedures for responsible research conduct and managing research misconduct

- management of collaborative research

- research requirements (DIIS, 2005).

Research in Australia is normally conducted under the auspices of the Australian Code for the Responsible Conduct of Research (NHMRC, 2018) and the National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research, (NHMCR, 2018b). Specific national and state legislation may also apply in the protection of participant rights, including relevant privacy laws. Depending on your targeted research population, specific reviews, approvals, and guidelines may also be required – for example, when working with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and communities. You’re responsible for ensuring you’re aware of and comply with the relevant legal and institutional requirements when conducting your research.

The National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research (NHMRC, 2018b) outlines four guiding principles for ethical research. You may want to compare your own research (or research you read about in journal articles) against these checklists to ensure you’re addressing the four guiding principles detailed below.

Research Merit and Integrity

Your research has merit if it is:

- justifiable by its potential benefit – e.g., contribution to knowledge and understanding, improved social welfare and individual wellbeing, within the skills and expertise of researchers

- designed/developed using methods appropriate for achieving the aims of the proposal

- based on a thorough study of the current literature (as well as previous studies)

- designed to ensure respect for the participants is not compromised by the aims of the research by the way it is carried out or by the results

- conducted or supervised by persons or teams with experience, qualifications, and competence that are appropriate for the research.

You are conducting your research with integrity if you and the research team are committed to:

- searching for knowledge and understanding

- following recognised principles of research conduct

- conducting the research honestly

- disseminating and communicating the results (whether favourable or unfavourable) in ways that permit scrutiny and contribute to public knowledge and understanding.

Your research is just if you:

- select, exclude, and include categories of participants fairly, and accurately describe the process in the results of your research

- recruit participants fairly

- ensure there is no unfair burden of participation in research on any particular group(s)

- fairly distribute the benefits of participating in the research

- do not exploit participants in the conduct of your research

- provide fair access to the benefits of the research

- make the research outcomes accessible to research participants in a way that is timely and clear.

Beneficence

Your research demonstrates beneficence if you:

- ensure there is likely benefit of the research to the participants, to the wider community, or both

- assess that the likely benefit of the results justifies any risk of harm or discomfort to the participants

- have designed the research to minimise the risk of harms or discomfort to the participants

- clarify for the participants the potential benefits and the risks of the research

- ensure the welfare of the participants (in the conduct of the research)

- suspend the research where the risks to participants are no longer justified by the potential benefits

- consider whether research should be discontinued or at least modified (in the event it’s suspended)

- notify the review body promptly if you do suspend the research.

Your research demonstrates respect if you:

- abide by the values of research merit and integrity, justice, and beneficence

- have due regard for the welfare, beliefs, perceptions, customs, and cultural heritage of individual (and collective) participants and groups involved in the research

- respect the privacy, confidentiality, and cultural sensitivities of the participants

- fulfil any specific agreements made with participants or their communities

- give due scope throughout the research process to the capacity of individuals to make their own decisions

- empower individuals where possible and protect them as necessary where they may be unable to make their own decisions or have diminished capacity to do so.

Processes of Ethical Review in Australia

Ethical review of human research can be undertaken at various levels, according to the degree of risk involved in the research, and the levels of review established at a research institution. In all cases, the ethical review of human research is undertaken in accordance with the guiding ethical principles and process of research governance and ethical review outlined within the National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research (2018b). With regard to the assessment of risk involved in research this involves:

- identifying any risks

- gauging their probability and severity

- assessing the extent to which they can be minimised

- determining whether they are justified by the potential benefits of the research

- determining how they can be managed.

You’ll be involved in identifying, gauging, minimising, and managing any risks involved in your project – normally as part of preparing and submitting your ethics application. The Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC) – or other ethical review bodies – will review your research proposal to make a judgement on whether the risks are justified by the potential benefits. Individuals you approach to participate in your research will also assess the risks associated with your research as they decide whether or not they consent to participate.

Research methodology and risk management

The research methodology you adopt for your project will be crucial in considering ethical risk and the management of this. There are two broad types of research – quantitative or qualitative methods – and both types of methods have different advantages and disadvantages. The choice of which method you will use is determined by your research question. This topic will explore some of the common approaches to research and some of the associated ethical issues to consider when adopting these.

Research can have an impact on participants both during the conduct of the research and after the research has been completed as they reflect upon their experience of participation (mental) and recovery from any physical demands (e.g., donation of human biospecimens, physical testing, etc.). While this list of potential risks is not exhaustive, some of the common risks are identified below. Risk of participation to a participant (or you and the research team) is generally classified along a continuum, with ‘Inconvenience’ – for activities such as the time required to fill out a survey or take part in an interview – at the low end of the scale, and ‘Harm’ – at the high end of the scale. ‘Discomfort’ is somewhere in the middle, and this can include both physical and psychological aspects. This could include side effects of drugs that participants may need to take in the research or even anxiety when attending a research interview.

All research must have a benefit that either directly or indirectly benefits individuals, groups, or society as a whole. Benefits of research can include gains in specific knowledge, improved individual wellbeing, or increases in the skill or expertise of an individual, group, or organisation. While your research may have no immediate benefit to the participants, it’s worth considering whether participants can benefit from self-reflection on the research topic. For example, you may be interested in parenting styles and discipline, and while your research may not have an immediate benefit to this group of participants, they may benefit from self-reflecting on their own parenting practices.

Managing Risks

Much of the research conducted using human participants will have some degree of remaining risk to a participant or the research, despite any mitigation strategies you’ve applied in the research design phase. Even if the remaining risk is minimal, it’s up to you to develop clear strategies for managing these remaining risks should they eventuate. This is not always an easy task as it can be difficult for you to know if a particular topic will cause distress or harm for an individual participant. Therefore, it’s important for you to think carefully about how you’ll support a participant if they become upset or distressed. You’ll also need to think carefully about government regulations and guidelines.

Ethics Risks – Confidentiality

You may be interviewing children about their television viewing habits when the child reveals information about child abuse. Would you know what to do in this situation? Do you have a legal obligation to report this disclosure? Who can you tell to protect the child while maintaining participant confidentiality?

Finally, when thinking about risks and benefits of the research, you’ll need to consider the following practical elements:

- What is the research theme or question that this project is designed to explore?

- Why is the exploration of this theme or answer to this question worth pursuing?

- How will the planned methodology and methods explore the theme or achieve the aims of the research?

Quantitative Methods

There are many different research methodologies, and the methodology you choose will depend on the research aims, questions, and/or hypotheses.

Research Surveys and Questionnaires

One of the most common methods for conducting research is surveys or questionnaires. In the past, participants would often complete pen-and-paper surveys and either hand them to the researcher or mail the survey to the researcher. Nowadays most researchers would use online survey software such as Qualtrics or Survey Monkey (it’s always best to check with your university to see what survey software they recommend – at USQ we use the USQ Survey Tool , which was developed from LimeSurvey ). Surveys/questionnaires can be quantitative when questions use a closed question format (e.g., Likert scales) or can be qualitative when an open question format is used. Many surveys/questionnaires can contain a combination of the two types of questions (mixed method).

Ethical risks to consider:

- How long will it take participants to complete the survey?

- Could the content of the questions cause/trigger psychological harms, economic harms, or legal harms to participants?

- Could the research cause social harm to participants? Is your survey/questionnaire voluntary and anonymous?

- How secure is the online survey software?

- Where will the data be collected, stored, and transferred? You’ll need to check the terms and conditions of the software licence to ensure you have full access and ownership of the data and are aware of relevant privacy laws.

Additional considerations:

- Make sure you have permission to use any measures or scales that you want to include in your survey or questionnaire – seek permission from the copyright owner as required.

- Ensure you have sufficient qualifications and/or experience to administer and/or analyse the data from the survey or questionnaire if this is a standardised test or test bank.

Ethics Risks – Genetic Testing

Your grandfather provided a human biospecimen 50 years ago for a research project. Advances in medical science mean that it’s now possible to predict with accuracy that you’ll acquire a certain illness. Would you feel comfortable with this information being published? Would you want to know this information?

Qualitative Methodologies

There are many different research methodologies, and the methodology you choose will depend on the research aims, questions, and/or hypotheses. A strength of qualitative research is that it permits a participant to describe their experiences in ways that are meaningful to them, rather than to group their experience using research-derived classifications (Shaughnessy et al. , 2006).

Research Interviews

Interviews involve conducting discussions with a small number of participants to explore a particular phenomenon of interest. Typically, there are three different types of interviews:

- structured interview s where there is a set of predetermined questions that all participants answer in the same order without any variation to the questions

- unstructured interviews where there are no predetermined questions, and the interview is quite informal and unstructured

- semi-structured interviews contain elements from both the structured and unstructured interviews. That is, there are some predetermined questions, but the interviewer can change the order of the questions or ask additional questions for further clarification or to expand on an issue that arises during the interview.

- It’s important to protect your participants’ identities, and this may be done through a process to remove any identifying information, such as replacing a participant’s name with the use of a pseudonym.

- Length of time it takes a participant to complete the interview. This might vary from 10 minutes to a couple of hours. Please try and keep interviews under one hour if you can and offer your participant breaks, water, or snacks if they need them.

- Talking to another person can arouse people’s emotions, and so you may need to consider this risk. That is, you’ll need to consider the content of the questions you’re asking: could they cause/trigger psychological harms, economic harms, or legal harms? Participants may also want to stop the interview if they find the questions distressing or upsetting. If you’re uncertain about whether a participant wants to continue – ask them. If you’re in doubt, you’ll need to stop data collection, contact your supervisors or other members of the research team, and you may need to make a report to your research institution’s ethics office. Remember, if a participant asks to stop an interview you must not under any circumstance try and cajole them into continuing.

- As a researcher, you’ll need to reflect on whether you have the skills to deal with an upset participant. Some topics should be left to interviewers with skills in psychology or counselling.

- Plan ahead and include information about appropriate referral services in the participant information sheet, even if you do not personally think a topic is distressing.

Recruitment and data collection

Recruiting participants in responsible ways is a core part of the research process and something to which careful attention is paid during assessment of the research ethics of a project. This topic will focus on the responsible recruitment of research participants and the collection of data from individuals.

Recruitment of Research Participants

The strategies you use to recruit your participants will be varied, and you’ll need to think carefully about the research methodology you’ve chosen and who your participants are. For example, are you approaching your work from a quantitative perspective? If so, then you’ll need to gather data from lots of participants and therefore your recruitment will need to be broad if you’re trying to take a sample that could be considered representative of a wider population.

If you’re drawing on qualitative methodologies, then your approach might be different in that you’ll likely be focusing on a much smaller number of participants who have a shared experience of a particular phenomenon and are therefore looking for a more homogenous sample. Your recruitment, in this case, would be more targeted.

You also need to carefully consider your inclusion and exclusion criteria for your participants. Do you, for example, want to focus on a particular age group, occupation, or social class? These criteria need to be made explicit in your application form to enable an accurate assessment of the risks associated with your research.

The strategies you choose to recruit your participants’ will also carry different levels of risk, and these need to be considered as part of your research design and ethics reflections.

Recruiting From Your Acquaintance Network

Recruiting people who you know, or friends of friends has the benefit of more straightforward access to your participants. However, one thing to consider if you’re planning to recruit participants through this strategy is social risk. Do the people who you approach feel obliged in some way to take part in the research? Will your relationship with them be compromised in any way if they either refuse to take part in the research or don’t provide the expected responses? Are these participants’ fellow employees within a company, for example, and are there issues of confidentiality and future impacts on working relationships that need to be considered?

These issues will, of course, be influenced again by your research design. If you’re planning a quantitative survey that is anonymous then the social risks will be reduced. However, if you’re planning to interview participants about a sensitive or personal topic then the social risks will be considered higher.

Vulnerable Participants

Some participants are more vulnerable than others in the research process, and as part of your ethics application, you’ll be asked to carefully consider who your target participants are and whether these comprise what are considered a vulnerable population. Such populations include research with a pregnant woman or foetus, children, people with cognitive impairment or mental illness, people considered to be a forensic or involuntary patient, people with impaired capacity for communication, incarcerated individuals or people on parole, those highly dependent on medical care or who are in hospital, military personnel or veterans, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, people in other countries or who would consider English to be a second language, and those who would not usually be considered vulnerable but would be considered vulnerable in the context of the proposed research project.

Children can provide a wealth of important information, but due to their age and cognitive immaturity, special attention needs to be given to safeguarding them in their participation in research. One crucial element is that of consent, which we’ll discuss a bit later in the chapter. Care and attention also need to ensure that the rights of children are protected in terms of confidentiality and potential coercion into participation in projects.

Research that is undertaken within schools may require the additional approval of the education governing body, and therefore careful attention needs to be paid to this in the research planning stages. Also, think carefully about the tasks you’re requiring the children to do. If a child (or their parents) does not consent to taking part in a school-based activity that will comprise the research, what equitable activity will you provide for them to do instead?

Recruitment of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples

There is great diversity across the many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures and societies. Application of core values and cultural and local protocols should be determined by the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities or groups involved in the research. This means you need to engage with the people or communities you want to research to discuss your proposed research and agree to the best way forward prior to seeking your ethical approval.

Unfortunately, that didn’t always occur in the past. Consider, for example, the Cambridge anthropology expedition to the Torres Strait that took place in the late nineteenth century, or later research with indigenous groups that had little contact with white Australian culture but were given tests of cognitive ability without considering how constructs such as intelligence may be expressed in different cultural settings (Dudgeon et al., 2014). In 2016, at the national Australian Psychological Society conference, the APS acknowledged the role psychology played in the mistreatment and erosion of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander culture.

It’s therefore important that if you’re undertaking research with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders, you think about the research collaboratively. You may find the Ethical Conduct in Research With Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples and Communities: Guidelines for Researchers and Stakeholders (NHRMC, 2018a) informative.

If you’re undertaking health research that is targeting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and communities, you must consult the above guidelines and may find the following useful: Keeping Research on Track II (NHMRC, 2018d) and the Guidelines for Ethical Research in Australian Indigenous Studies (Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies [AIATSIS], 2012).

When you think of obtaining consent, what comes to mind? You may indicate that it could involve signing a consent form prior to taking part in the research. While this is a common component of obtaining consent, this may not be suitable – or even practical – if you propose to administer an online survey. Therefore, a well-designed consent strategy will need to be tailored to your potential participants and fit with your research methodology and research methods. Consent should also be viewed as a process, rather than a single point in time event. That is, obtaining consent may be a component of the processes you undertake when consulting, engaging, and negotiating to prepare for your research conduct. This will be especially relevant in the context of research involving Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and communities.

The requirement for consent is a relatively new concept, having evolved predominantly through unscrupulous researchers using a participant as a means to an end – for example, the Tuskegee researchers we discussed earlier in the chapter. Subsequently, international and national guidelines, such as the Belmont Report (National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioural Research, 2012) and the National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research, 2007 (updated 2018) (NHMRC, 2018b) have been produced to empower and protect participants to make an informed decision about their participation in research.

Elements of Consent

When obtaining consent from a participant, you need to ensure that it’s provided voluntarily. That is, that the individual has agreed to take part in the research as a result of having being provided sufficient information, understood that information, and not been coerced (or felt pressured), nor overly enticed to partake (through inappropriate incentive or reward).

This raises a number of decision points that you’ll need to work through, for example:

- How much information do I need to provide about the study?

- How will I obtain voluntary participation?

- Who will be involved in recruiting the participants?

- How will I ascertain if the participant understands the information I’ve provided about the project?

- Does the participant have any expectations about the outcomes of the project – for example, in medical research, will they be expecting treatment of a known condition or illness, versus understanding they’re participating in research and may be assigned to a control (i.e., no treatment group)?

- Who needs to be involved in the decision to provide consent? E.g., Will all participants have the capacity for understanding and/or the legal capacity to provide consent? If not, when do others need to be involved in this decision? This would involve situations where the participant lacks the capacity to provide consent, e.g., elderly person with dementia.

Consent Approaches