Dogs: History, evolution and behavior of our best friends

Dogs and humans have been companions for thousands of years.

When were dogs domesticated?

- Do dogs see color?

Can dogs feel emotions?

How smart are dogs, how do dogs help people, additional resources.

It hardly seems like a dainty teacup poodle and a wrinkly Neapolitan mastiff could belong to the same species, much less the same subspecies. But both are Canis lupus familiaris , the beloved domestic dog.

A member of the family Canidae — along with wolves, foxes, coyotes and jackals — dogs have been human companions for at least 14,000 years (and possibly much longer than that). Much about how dogs and humans became inseparable remains a mystery, but research finds that the bond is very real. As many pet owners may already attest, there is evidence that dogs understand human distress and want to help their owners when they're sad.

Despite the diversity of domestic dogs, these animals share an evolutionary history and behavioral traits.

The closest living relative to modern dogs is the gray wolf ( Canis lupus ). The ancestor of modern dogs and the ancestor of modern wolves probably split at some point in the late Pleistocene , the last ice age. Genetic studies put different dates on this split. One 2014 study based on the mutation rates found that the schism happened between 9,000 and 34,000 years ago, and that the wolf population dogs split from later went extinct . Another genetic study from 2017 put the window between 20,000 and 40,000 years ago.

The oldest fossil that scientists agree came from a dog, rather than a wolf, comes from a site in Germany called Bonn-Oberkassel and dates back about 14,200 years . But archaeologists have found fossil specimens that might be domesticated dogs dating back more than 30,000 years . It's difficult to confidently identify a Pleistocene fossil fragment as being from either a dog or a wolf, and because dogs and wolves interbred even after they diverged genetically, genomic studies are complicated. Researchers also debate whether dog domestication happened once or at multiple sites around the world.

"We don't know where in the world it happened," Anders Bergström, a postdoctoral fellow in ancient genomics at the Francis Crick Institute in London, told Live Science in 2022 . "We don't know what human group was involved, and we don't know whether it happened once or multiple times."

It is clear that humankind's bond with dogs goes way back. The 14,200-year-old dog from Bonn-Oberkassel was buried with two humans and had been nursed through several episodes of canine distemper before it died. In a 12,000-year-old cemetery in Israel, a woman was found buried with her hand on a small wolf or dog puppy . A Stone Age dog from what is now Sweden was buried with a human companion about 8,400 years ago, researchers reported in 2020.

What are dog breeds?

In the time since domestication, humans have shaped dogs like clay: Sometimes it seems like the only things different dog breeds have in common are four legs and a tail. The American Kennel Club (AKC) currently recognizes 200 breeds , and that list doesn't even begin to touch the diversity of hybrid breeds (Labradoodles, anyone?) and uncategorizable mutts (often the best kind).

The AKC isn't the final arbiter of what makes a dog breed. According to the organization, there are some 400 dog breeds registered around the world. AKC registration just means there are enough of a certain breed in the United States and enough interest from owners in documenting a breeding history and a "breed standard," which is a description of the ideal characteristics of a breed.

Picking dogs with certain traits and breeding to maximize those traits has led to dogs specialized for many different tasks. Labrador retrievers, for example — which often top the lists of most popular breeds in the United States — have webbed toes and a two-layered coat that is resistant to water. These are traits left over from the breed's original role of retrieving downed ducks for duck hunters. According to the AKC , Labradors were bred from the St. John's dog, a water-loving breed used in early Newfoundland fisheries to retrieve nets and lines.

The sausage-like dachshund, on the other hand, is a poor swimmer but a keen hunter. It was bred for its narrow body and digging acumen, all the better for burrowing into badger dens and killing the occupants, according to the AKC .

Though most official modern breeds date back to the Victorian era, a 2010 paper did find divergence between some breeds indicating that they emerged 500 or more years ago. These breeds were the basenji, Afghan hound, Samoyed, saluki, Canaan dog, New Guinea singing dog, dingo (a wild canine), chow chow, Chinese shar-pei, Akita, Alaskan malamute, Siberian husky and American Eskimo dog.

Do dogs see color? (And other dog senses)

Dogs can see yellow and green hues , but they can't distinguish red from green — a similar situation to humans who are red-green color-blind. However, dogs may be more sensitive to ultraviolet light than humans are, according to 2014 research , in which case they would be better at sensing a wider ranges of blues than people are.

Dog vision is almost three times blurrier than human vision, according to a 2017 study . In that research, whippets, pugs and Shetland sheepdogs were trained with treats to distinguish lines that were different distances from one another. These lines were then used to give the dogs a visual test, not unlike the alphabet chart a human might see during a visit to the eye doctor. Dogs had about 20/50 vision, the study found, meaning that something a human could see clearly at a distance of 50 feet (15 meters), a dog could see clearly at 20 feet (6 m). Dogs, however, do see better than people in dim light, according to the Merck Manual for Veterinary Medicine , and can see movement better, too. One special feature that magnifies light to a dog's eye is the tapetum lucidum, a reflective layer that also gives dogs their characteristic eyeshine at night.

Hearing and smell are where dogs really shine. According to the Merck Manual, dogs hear about four times better than humans do. Incredibly, their sense of smell is a whopping thousand to ten thousand times better than ours. The olfactory center of a dog's brain is 40 times the size of the olfactory center in a human's brain. Because dogs can distinguish between smells with great sensitivity, they have been trained to sniff out human diseases: researchers discovered in the early 2000s that dogs can sniff out signs of early stage cancers , and in 2021 scientists found that dogs could identify COVID-19 in the scent of urine samples, Live Science previously reported.

Humans and dogs really do understand each other. A 2014 study found that emotional processing regions of dogs' brains respond to human emotional sounds , like laughing and crying, in the same way as these regions respond to dog emotional sounds, like whining or yipping. Humans, too, process dog emotional sounds in the same way they process human emotional sounds.

But what emotions do dogs feel? And what do they understand about others' emotions?

It's pretty clear that dogs experience basic emotions, like pleasure, sadness, anxiety and fear, said Julia Meyers-Manor, a psychologist at Ripon College in Wisconsin who studies animal emotions. Meyers-Manor led a 2018 study that found that dogs showed stress in response to their owners' crying noises and that dogs were more likely to attempt to comfort or help a crying owner compared with a laughing owner. Follow-up research that has not yet been published suggests that dogs attempt to comfort upset strangers, too, though not as readily as they comfort their owners, Meyers-Manor told Live Science.

"There's quite a bit of consistency in brain areas that process emotions across mammal species," she said. Dogs are social animals, so it's not surprising that they'd respond to the emotions of others. It is interesting, however, that dogs respond to emotions across species, she said. It's possible that crying is similar enough among species to elicit a response no matter what animal is crying and what animal is listening, she said. It's also possible that, because dogs have co-evolved with humans for so long, they're particularly good at interpreting human emotion. More research comparing different species' reactions is needed to clear up these questions, Meyers-Manor said.

Despite these similarities, one thing is certain: Your dog probably doesn't feel guilt when it digs up the flower beds and knocks over the trash. Though many dog owners take the pitiful, droopy-eyed look a dog gives when it senses trouble to mean that their dogs know exactly what they did wrong, a 2009 study found that the guilty look is simply a way to stay out of trouble. In that study, dogs were put into situations where they were framed for doing something wrong, like eating a forbidden treat. Even when the dogs had not eaten the treat, they looked guilty when their owners thought they had and scolded them.

In other words, the expression that humans interpret as guilt is nothing of the sort. It's just a reaction to a scolding human. "They've just learned, make this expression when there's a big mess in the house and owners won't kill you," Meyers-Manor said.

Dogs are pretty smart, though not "exceptional," according to a 2018 study in the journal Learning & Behavior . The study compared dogs with other carnivores, with other social hunters, and with other domesticated animals, looking at definitions of intelligence that covered sensory cognition, physical cognition, spatial cognition, social cognition and self-awareness. These comparisons focused on other species for which intelligence studies had been conducted, which mainly included wolves, hyenas, African wild dogs, cats , bottlenose dolphins, chimpanzees , horses and pigeons.

On the whole, the researchers concluded, dogs have sensory abilities similar to those of other hunting carnivores. They're pretty bad at solving problems involving objects, such as pulling a string to get at a treat attached to the other end. Spatial cognition, which involves understanding places and navigation, was harder to compare, the researchers found, but there did not seem to be any evidence that dogs were standouts compared with other hunters. Dogs were impressive at using other animals' behavior to cue their own and did beat out many other similar animals at social learning, though dolphins and chimps might be better at imitation. Finally, unlike dolphins and chimpanzees, dogs don't show many signs of self-awareness, or the ability to project themselves mentally into the past or future by remembering events like a story or planning for future events.

Dog smarts are about what would be expected from a domesticated social carnivore and hunter, the researchers concluded in their paper. Dogs are socially savvy, paying attention to cues from other dogs and from humans, their evolutionary co-pilots. They have sensory abilities and spatial smarts sufficient to navigate the environment of a pack hunter. But they aren't as good at things that don't matter as much to their survival, such as figuring out how objects work or making detailed plans for the future.

Humans and dogs have been working together for a long time. Though the earliest history of dogs is shrouded in mystery, there are hints that humans may have used dogs to help with hunts as long as 14,000 years ago, according to a 2019 study in the Journal of Anthropological Archaeology . In Saudi Arabia, rock art estimated to be about 8,000 years old shows humans hunting with dogs on leashes, killing ibex and gazelles, ScienceAlert reported .

— Why is chocolate bad for dogs?

— Are cats or dogs smarter?

— Dogs know when humans are lying to them

Today, dogs still help hunters stalk quarry large and small. Labrador retrievers continue to be used to hunt ducks, while sprinters such as the Pharaoh hound are excellent at catching prey such as rabbits.

Dogs are also used by police and the military, often to sniff out drugs or explosives, to perform search and rescue operations, and to bite and hold suspects. According to the AKC , police dogs are usually breeds that have been bred to be highly trainable, including German shepherds, Labrador retrievers, and bloodhounds.

Modern dogs also play a huge role as service dogs, therapy dogs and emotional support animals. Guide Dogs or Seeing Eye Dogs help people with vision loss navigate obstacles. Therapy dogs are used to support and calm people with autism, post-traumatic stress disorder, anxiety and other conditions. There are even squads of good-natured dogs roaming airports (with their handlers, of course), calming nervous travelers with snuggles.

Check out the Humane Society of America for more on pet dog behavior and welfare. The American Kennel Club is an exhaustive reference on dog breeds, health, and training. For a deep and detailed dive into what scientists know (and don't) about how dogs were domesticated and came to the Americas, read the 2021 paper " Dog domestication and the dual dispersal of people and dogs into the Americas ," which is freely available.

Originally published on Live Science.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Stephanie Pappas is a contributing writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience to archaeology to the human brain and behavior. She was previously a senior writer for Live Science but is now a freelancer based in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie received a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Why do dogs sniff each other's butts?

Genetic quirk in 25% of Labrador retrievers can lead to overeating, obesity

Earth-size planet found orbiting nearby star that will outlive the sun by 100 billion years

Most Popular

- 2 Black hole singularities defy physics. New research could finally do away with them.

- 3 Snake Island: The isle writhing with vipers where only Brazilian military and scientists are allowed

- 4 Newfound 'glitch' in Einstein's relativity could rewrite the rules of the universe, study suggests

- 5 James Webb telescope spots 2 monster black holes merging at the dawn of time, challenging our understanding of the universe

- 2 Does the Milky Way orbit anything?

- 3 'More Neanderthal than human': How your health may depend on DNA from our long-lost ancestors

- 4 The mystery of the disappearing Neanderthal Y chromosome

- 5 Scientists discover bizarre region around black holes that proves Einstein right yet again

clock This article was published more than 2 years ago

Thinking about how dogs think

Back in 2002, when Alexandra Horowitz was working toward her PhD at the University of California at San Diego, she believed that dogs were a worthy thing to study. But her dissertation committee, which favored apes and monkeys, needed convincing.

“They were primate people,” she said. “They all studied nonhuman primates or human primates, and that’s where it was thought that the interesting cognitive work was going to happen. Trying to show them that there would be something interesting with dogs — that was a challenge.”

Oh, how things can change in just two decades, especially in a nation that includes about 90 million dogs among its residents — everything from beloved pets to working dogs doing all kinds of tasks, from sniffing out drugs in airports to assisting blind people with crossing a street. Today, Horowitz is a senior research fellow at Barnard College in New York City, where her specialty is dog cognition: understanding how dogs think, including the mental processes that go into tasks such as learning, problem-solving and communication. Dog cognition is now a widely respected field, a growing specialty branch of the more general animal-cognition research that has existed since the early 20th century.

“This field, and animal cognition, really, is all within our lifetimes,” Horowitz said. “It’s not as if nobody ever looked at dogs, but they weren’t looking at their minds.”

Looking at dogs’ minds, so far, has revealed quite a few insights. The Canine Cognition Center at Yale University, using a game where humans offer dogs pointing and looking cues to spot where treats are hidden, showed that dogs can follow our thinking even without verbal commands. The Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology in Germany figured out that dogs are smart about getting what they want — they will eat forbidden food more frequently if humans can’t see them. Researchers from Austria, Israel and Britain determined that seeing a caregiver, versus a stranger, activated dogs’ brain regions of emotion and attachment much as it does in the human mother-child bond. Other European researchers showed that negative-reinforcement training (like jerking on a leash) causes lingering emotional changes and makes the dog less optimistic overall.

Read more stories of dogs, humans and the relationship they share

Some dog owners hear about this type of research and think: “They did a whole study to figure out that my dog looks where I point? I could have told you that.” But the studies aren’t just about what a dog is doing. They’re indicating areas to research so that we can better understand why and how the dog is doing it — in other words, what’s happening inside the dog’s mind.

“Maybe they’re not looking at your finger at all. Maybe they’re paying attention to your face and not to your hand,” said Federico Rossano, whose team at the University of California at San Diego is trying to determine whether dogs can translate their thoughts into words that humans can understand through a language device. “A lot of this becomes interesting in terms of how you can train them better.”

An evolving area of research

Right now, with no organizing body in the field, it’s hard to say exactly how many people are doing dog-cognition research. You can count on two hands the number of dedicated university spaces led by professors with graduate students and funding grants. When the leaders from those places get together once a year, it’s usually at someone’s home.

But researchers at universities doing studies on dogs? There are now many dozens of those, and there’s no lack of students wanting to at least dabble in the work.

“The thing that gets my students all abuzz is that people always want to know whether their dog loves them back,” said Ellen Furlong, associate professor of psychology at Illinois Wesleyan University and leader of its Dog Scientists Group.

Every semester, on the first day, she asks students if their dogs are happy. It’s her way of helping them understand why the study of dog cognition is important.

“They’re always kind of offended — ‘O f course my dog is happy. I love my dog,’ ” she said. “But then you dig a little bit and push them and say: ‘Your dog’s life is different from your life. You get to decide when your dog gets to eat and play and go outside. You decide everything about your dog’s life, but your dog isn’t human. They have different wants and needs than you do.’ They have a semester-long assignment where they have to consider how their work on cognition can help to design some enrichment activities to improve the dogs’ lives.”

The topics that dog-cognition researchers focus on today often are chosen based on personal interests. While Furlong is most curious about ethics, welfare and how humans can meet dogs’ psychological needs, Horowitz is focusing her research on what dogs understand through smell. At the Duke Canine Cognition Center in North Carolina, Brian Hare is trying to determine — when a dog is still a puppy — whether the way a dog thinks might make her a good candidate for different jobs as an adult.

“We’re saying, ‘Here are some cognitive abilities that are critical for training for these jobs,’ ” Hare said. “It’s a little bit like talking about personality, but we’re talking about your cognitive personality, in a way. Maybe you have a really good memory for space, or maybe you’re good at understanding human gestures. The question is whether we can identify some of these dogs really early, in the first two to three months of life, who will do well in these programs.”

How the research is done

One example of dog cognition research with a potential training application is a study that Horowitz did on nose work — an activity that lets dogs use their natural abilities with scents to find everything from a treat hidden under a cone to marijuana in somebody’s suitcase.

Horowitz and her team showed the dogs three buckets and taught them that one of the buckets always had a treat under it, and one did not. Then she measured how quickly the dogs went to the “ambiguous bucket” in the middle.

The dogs then attended nose-work classes. These types of advanced classes are widely available at the same types of schools that teach basic obedience. In the nose-work classes, dogs are encouraged and trained to use their noses to search for and find treats or favorite toys that are hidden under boxes or cones, inside suitcases or in other places.

After a few weeks of nose-work classes, Horowitz repeated the bucket test.

“What we found was the dogs in the nose-work class got faster at approaching ambiguous stimulus,” she said, adding that the results suggest that for some dogs, taking nose-work classes could help them feel more optimistic. “The group that had nose work changed their behavior afterward, so I have to say it’s something about the nose work. I don’t know exactly what it was, but if the effect is profound and we keep seeing it, we would go in and try to see what it was that made it useful for the subjects.”

Hare is widely credited with having jump-started America’s dog-cognition research field. In the late 1990s as an undergraduate, he was doing research with chimpanzees when he realized they couldn’t do something that his dogs could do: follow a human’s pointing gesture to find food. Chimpanzees are the closest animal relatives humans have, and dogs could do something they couldn’t. Researchers suddenly wanted to know why dogs could understand something that chimpanzees could not.

In his most recent study , published in July, Hare and his team looked at the difference between wolf and dog pups. There had been some debate in the dog-cognition field about where dogs’ unusual abilities to cooperate with humans originate — whether those abilities are biological or taught. So the team gave a battery of temperament and cognition tests to dog and wolf puppies that were 5 weeks to 18 weeks old. The pups of both species were given the chance to approach familiar and unfamiliar humans to retrieve food; to follow a human’s pointing gesture to find food; to make eye contact with humans, and more. The team found that even at such a young age, the dog pups were more attracted to humans, read the human gestures more skillfully, and made more eye contact with humans than the wolf pups did.

The conclusion? The way that humans domesticated dogs actually altered the dogs’ developmental pathways, meaning their abilities to cooperate with us today are biological — a research result that is likely to have many practical implications.

“It’s highly inheritable, and it’s potentially manipulatable through breeding,” Hare said, adding that dogs might be bred to specialize in certain types of thinking. The finding opens up the idea of studying dogs in ways that could make deep-pocketed entities like the U.S. government want to fund more dog-cognition research, Hare said.

By way of example, he talked about dogs he has worked with for the U.S. Marine Corps, compared with dogs he has worked with for Canine Companions for Independence in California. The Marines needed dogs in places like Afghanistan to help sniff out incendiary devices, while the companions agency needed dogs that were good at helping people with disabilities.

Just looking at both types of purpose-bred dogs, most people would think they’re the same — to the naked eye, they all look like Labrador retrievers, and on paper, they would all be considered Labrador retrievers. But behaviorally and cognitively, because of their breeding for specific program purposes, Hare said, they were different in many ways.

Hare devised a test that could tell them apart in two or three minutes. It’s a test that’s intentionally impossible for the dog to solve — what Star Trek fans would recognize as the Kobayashi Maru. In Hare’s version, the dog was at first able to get a reward from inside a container whose lid was loosely secured and easy to dislodge; then, the reward was placed inside the same container with the lid locked and unable to be opened. Just as Starfleet was trying to figure out what a captain’s character would lead him to do in a no-win situation, Hare’s team was watching whether the dog kept trying to solve the test indefinitely, or looked to a human for help.

“What we found is that the dogs that ask for help are fantastic at the assistance-dog training, and the dogs that persevere and try to solve the problem no matter what are ideal for the detector training,” Hare said. “It’s not testing to see which dog is smart or dumb. What we’ve been able to show is that some of these measures tell you what jobs these dogs would be good at.”

What comes next in the field of dog-cognition research is probably a bit more of everything. Some researchers are following their interests, while others are following the research grants. Those grants can come from a wide array of sources, including the government trying to help soldiers with post-traumatic stress disorder, shelters trying to rehome animals and neuroscience institutes looking for insights across species.

“It’s a really exciting moment,” Hare said. “I think we can continue on with individual researchers pursuing fun, interesting things — the students and the universities love it — but most successful academic endeavors have two parts. Being intellectual is wonderful, but that kind of research tends to struggle with funding. Academic endeavors with practical application tend to be incredibly well funded, and then the field grows.

“If you can have both of those things, then it will grow, and it will grow phenomenally,” he added. “If it’s just, ‘We’re going to do this because people love dogs,’ that’ll be fun, but it will stay small like it is now.”

Research in a Nutshell

What’s in a Name? Effect of Breed Perceptions & Labeling on Attractiveness, Adoptions & Length of Stay for Pit-Bull-Type Dogs

Comparison of behavioural tendencies between “dangerous dogs” and other domestic dog breeds–Evolutionary context and practical implications

Dog behavior and animal shelters, no better than flipping a coin: reconsidering canine behavior evaluations in animal shelters, what is the evidence for reliability and validity of behavior evaluations for shelter dogs a prequel to “no better than flipping a coin.”, saving normal: a new look at behavioral incompatibilities and dog relinquishment to shelters.

Never miss any important news. Subscribe to the Canine Behavior Science and Policy Newsletter.

Top Research Categories

Visual breed identification.

Comparison of visual and DNA breed identification of dogs and inter-observer reliability

This study examined both inter-rater reliability between experienced canine professionals and validity of visual breed identifications compared to DNA profiles—both were very low.

A canine identity crisis: Genetic breed heritage testing of shelter dogs

Visual Breed Identification: A Literature Review

Rethinking dog breed identification in veterinary practice

Breed-specific policies.

Looking for safety in all the wrong places: India’s new ban on 23 dog breeds cannot succeed

Thankfully, banning dogs of certain breeds is increasingly rare. But when this choice is made, as with the recent national BSL legislation in India, we

Eighth Circuit Court Fails to Protect Dog Owners’ Rights

Red herrings and just plain lies: Insurance companies vs. dog loving families

“What kind of dog is that?” Asking the wrong question and answering it badly

Breed-specific legislation is myth-based and ineffective according to the american veterinary society of animal behavior (avsab), talking with canine behavior scientists, additional research.

Dog Bite-Related Fatalities: A Literature Review

Enrichment centered on human interaction moderates fear-induced aggression and increases positive expectancy in fearful shelter dogs

Differences in Trait Impulsivity Indicate Diversification of Dog Breeds into Working and Show Lines

Associations between domestic-dog morphology and behaviour scores in the dog mentality assessment

Dog behavior co-varies with height, bodyweight and skull shape

Efficacy of drug detection by fully-trained police dogs varies by breed, training level, type of drug and search environment

Performance of Pugs, German Shepherds, and Greyhounds (Canis lupus familiaris) on an odor-discrimination task

Accurate & Reliable Source For Understanding Canine-Related Behavior Science

National Canine Research Council is a non-profit canine behavior science and policy think tank that focuses on the relationship between dogs and people. Our mission is to underwrite, conduct and disseminate academically rigorous research that studies dogs in the context of human society.

- Empirically-verified data

- Research that embodies the principle that dogs must be considered in relation to humans

- Removing barriers to safe and humane pet ownership

- Leading experts in the field

Canine Behavior Research & Policy eNewsletter

© 2016-2020 National Canine Research Council, LLC. Trade/service marks are the property of National Canine Research Council. All rights reserved.

Domestic dog

What is a domestic dog.

The term “domestic dog” refers to any of several hundred breeds of dog in the world today. While these animals vary drastically in appearance, every dog—from the Chihuahua to the Great Dane—is a member of the same species, Canis familiaris . This separates domestic dogs from wild canines , such as coyotes, foxes, and wolves.

Domestic dogs are mostly kept as pets, though many breeds are capable of surviving on their own, whether it’s in a forest or on city streets. A third of all households worldwide have a dog, according to a 2016 consumer insights study . This makes the domestic dog the most popular pet on the planet.

Evolutionary origins

All dogs descend from a species of wolf, but not the gray wolf ( Canis lupus ), like many people assume. In fact, DNA evidence suggests that the now-extinct wolf ancestor to modern dogs was Eurasian . However, scientists are still working to understand exactly what species gave rise to dogs.

When dogs broke off from their wild ancestors is also a matter of mystery, but genetics suggest that it occurred between 15,000 and 30,000 years ago.

While it’s impossible to say exactly how a wild wolf species became a domesticated dog, most scientists believe the process happened gradually as wolves became more comfortable with humans. Perhaps wolves started down this path simply by eating human scraps. Many generations later, humans might have encouraged wolves to stay near by actively feeding them. Later still, those wolves may have been welcomed into the human home and eventually bred to encourage certain traits. All of this is thought to have unfolded over thousands of years.

Today, many of the dogs you know and love are the product of selective breeding between individuals with desirable traits, either physical or behavioral. For instance, around 9,500 years ago , ancient peoples began breeding dogs that were best able to survive and work in the cold. These dogs would become the family of sled dogs—including breeds such as huskies and malamutes—that remains relatively unchanged today.

Similarly, humans bred German shepherds for their ability to herd livestock, Labrador retrievers to help collect ducks and other game felled by hunters, and sausage-shaped Dachshunds for their ability to rush down a burrow after a badger . Many more breeds were created to fill other human needs, such as home protection and vermin control.

Certain breeds have also been created to make dogs more desirable as companions. For instance, the labradoodle, which combines the traits of a Labrador retriever and a poodle, was invented as an attempt to create a hypoallergenic guide dog .

Modern working dogs

While people rely less on dogs for daily tasks than they did in the past, there are still many modern jobs for pooches.

Because the domestic dog’s sense of smell is between 10,000 and 100,000 better than our own, canines now assist law enforcement by sniffing out drugs, explosives, and even electronics . They can also help conservationists find and protect endangered species using their super-powered schnozzes.

They assist search and rescue teams in the wake of natural disasters or reports of people lost in the outdoors. Dogs trained to warn of hidden explosives and enemies serve as allies in military operations . Other dogs assist police looking for jail escapees or the bodies of murder victims. Some partner instead with customs officials searching for contraband, from drugs to elephant ivory . Still others lead the way tracking down poachers , patrolling cargo ships for rats that might escape at distant harbors, or exposing forest insect pests in shipments of wood from abroad.

Similarly, dogs can sniff out early signs of Parkinson’s disease, diabetes, several types of cancer , oncoming epileptic seizures , and antibiotic-resistant bacteria . They guide deaf and blind people, and they help people with autism and post-traumatic stress disorder manage with anxiety.

Living with dogs

Most dogs are a mix of breeds—in 2015, one study estimated that only 5 percent of dogs in shelters are purebred. Just as dogs come in all sizes, shapes, and colors, these animals also come in a spectrum of temperaments. A bulldog might look fierce but be cuddly as a kitten, whereas a cute cocker spaniel might nip at your finger without thinking twice.

This is why animal handling expert Jack Hanna recommends teaching children to always exercise caution around a dog they do not know. For instance, he says kids should ask for permission from the dog’s owner before trying to pet or play with the animal. Offering an outstretched hand also allows the dog to familiarize itself with a new person before reaching behind its head where it can’t see what you’re doing, which might make a dog nervous or scared. Finally, never allow children to put their faces near the dog’s muzzle.

“I don’t care what kind of dog it is,” Hanna told National Geographic . “The owner may say, ‘Well, this dog’s never bit anyone before.’ But that’s not the point. The point is it can happen.”

Of course, when dogs are cared for properly and treated with respect, they can be incredibly loving, playful, and intelligent companions. What’s more, by understanding where dogs come from, pet owners might learn to appreciate their canines even more.

After all, the yipping and tail-wagging your dog performs when you grab a bag of treats are carry-overs from when its ancestors needed to communicate with other members of its social group. Chasing sticks and balls may be linked to the pursuit of prey, while digging at the carpet or a dog bed echoes how a wild canid would prepare its sleeping area. And each time Fido stops to sniff a fire hydrant on your walk, it’s analyzing the pheromones left behind by another dog’s urine.

We take these behaviors for granted because dogs have become “man’s best friend.” But deep inside every pit bull and Pomeranian, there lie hints of the past.

Editor's note: Bringing a dog into your household is a major responsibility. More than 1.6 million dogs ended up in shelters in 2020. Learn how to keep your dog happy and healthy with the National Geographic book Complete Guide To Pet Health, Behavior, and Happiness .

- Environment

- Perpetual Planet

History & Culture

- History & Culture

- History Magazine

- Mind, Body, Wonder

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- Your US State Privacy Rights

- Children's Online Privacy Policy

- Interest-Based Ads

- About Nielsen Measurement

- Do Not Sell or Share My Personal Information

- Nat Geo Home

- Attend a Live Event

- Book a Trip

- Inspire Your Kids

- Shop Nat Geo

- Visit the D.C. Museum

- Learn About Our Impact

- Support Our Mission

- Advertise With Us

- Customer Service

- Renew Subscription

- Manage Your Subscription

- Work at Nat Geo

- Sign Up for Our Newsletters

- Contribute to Protect the Planet

Copyright © 1996-2015 National Geographic Society Copyright © 2015-2024 National Geographic Partners, LLC. All rights reserved

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- 28 April 2022

Massive study of pet dogs shows breed does not predict behaviour

- Freda Kreier

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Dog enthusiasts have long assumed that a dog’s breed shapes its temperament. But a sweeping study comparing the behaviour and ancestry of more than 18,000 dogs finds that although ancestry does affect behaviour, breed has much less to do with a dog’s personality than is generally supposed 1 .

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 51 print issues and online access

185,98 € per year

only 3,65 € per issue

Rent or buy this article

Prices vary by article type

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

doi: https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-022-01193-1

Morrill, K., et al. Science 376 , eabk0639 (2022).

Google Scholar

Download references

Reprints and permissions

Related Articles

- Animal behaviour

Parental-care puzzle in mice solved by thinking outside the brain

News & Views 15 MAY 24

These parrots go on killing sprees over real-estate shortages

Research Highlight 10 MAY 24

Puppy-dog eyes in wild canines sparks rethink on dog evolution

News 05 MAY 24

Pig-organ transplants: what three human recipients have taught scientists

News 17 MAY 24

The rise of baobab trees in Madagascar

Article 15 MAY 24

Powerful ‘nanopore’ DNA sequencing method tackles proteins too

Technology Feature 08 MAY 24

Senior Postdoctoral Research Fellow

Senior Postdoctoral Research Fellow required to lead exciting projects in Cancer Cell Cycle Biology and Cancer Epigenetics.

Melbourne University, Melbourne (AU)

University of Melbourne & Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre

Overseas Talent, Embarking on a New Journey Together at Tianjin University

We cordially invite outstanding young individuals from overseas to apply for the Excellent Young Scientists Fund Program (Overseas).

Tianjin, China

Tianjin University (TJU)

Chair Professor Positions in the School of Pharmaceutical Science and Technology

SPST seeks top Faculty scholars in Pharmaceutical Sciences.

Chair Professor Positions in the School of Precision Instruments and Optoelectronic Engineering

We are committed to accomplishing the mission of achieving a world-top-class engineering school.

Chair Professor Positions in the School of Mechanical Engineering

Aims to cultivate top talents, train a top-ranking faculty team, construct first-class disciplines and foster a favorable academic environment.

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Read our Dog Testing FAQ

Our new Dog FAQ page provides answers to the most frequently asked questions about dogs in research.

Dogs ( Canis familiaris ) belong to the family Canidae and are thought to be one of the first domesticated animals. They have been used in research for more than a century, however, they are currently very rarely used in animal research in Great Britain, only being used in 0.24% of experimental procedures in 2019 (latest published figures).

They are medium-sized mammals that can grow from 15 to 100 cm and weigh from 1.5 to 75 kg, depending on the type of dog. Dogs are carnivores but can thrive on a well-designed suitably processed omnivorous diet in the domestic situation.

Why are dogs used in research?

In the UK, dogs are primarily used to find out how new drugs act within a whole, living body and whether new medicines are safe enough to test in humans. They predict this safety very well, with up to 96% accuracy .

This is done to satisfy safety regulations which came about after the drug Thalidomide maimed and killed children while they were still in the womb. It is known as toxicology testing, but normally seeks to confirm the absence of toxic effects.

The tests can tell us lots of sorts of information all at once, like the safety if a drug across lots of different internal organs, how the drug travels around the body and other information that helps us to design much safer human trials.

Dogs are also used to test the safety and efficacy of veterinary medicines, and also in nutrition studies to ensure that pet dogs eat healthily, particularly when they are prescribed specialist diets by their vets.

Although animal and nonanimal methods are used alongside each other, there are currently no alternatives to using dogs. They nevertheless have special protections under UK law. For instance, they cannot be used if another animal species could be used.

There is a project that hopes to create a ‘virtual dog’ that could significantly reduce the number of dogs needed by using computers to mine historical dog data. It is being run by the UK’s national centre for developing animal replacements, the NC3Rs , but is of international interest.

What types of research are dogs used in?

The physiological similarities between humans and dogs mean that they are useful in various types of research. Their genome has been sequenced and because of our genetic similarities, they are often used in genetic studies.

Dogs are primarily used in regulatory research, also known as toxicology or safety testing. This type of research is required by law to test the safety and effectiveness of potential new medicines and medical devices before they are given to human volunteers during clinical trials. Dogs are also used to test the safety and efficacy of veterinary medicines, and also in nutrition studies to ensure that pet dogs eat healthily, particularly when they are prescribed specialist diets by their vets.

A smaller number of dogs are also used in translational research (also called applied research) to help us learn about human and animal diseases so that we can develop treatments. Examples of translational diseases can be found below.

Dogs are also used to study Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), which is the most common type of muscular dystrophy. It is another condition that can affect both humans and dogs. Because dogs can naturally have this condition, they can be studied to show how the condition progresses. This very useful model for DMD has helped scientists work on better genetic tests and treatments for the condition.

An early use of dogs in research was in the search for a treatment for diabetes, which resulted in the discovery of insulin. This discovery in the 1920s, which won researchers a Nobel prize, now allows people with diabetes to live long lives. In the past, people with diabetes would die soon after developing the condition.

How are the dogs looked after?

The use of animals in research is highly regulated, an important part of that regulation is ensuring the animals are housed and cared for correctly. Laboratory dogs are housed in enclosures that can isolate individual dogs for treatment but usually opened up for dogs to interact. Dogs’ need to socialise is well considered, so the dogs are housed in small groups most of the time. The facilities usually also have space to run around for exercise and you can usually find dogs interacting with each other, environmental enrichments, and the animal technicians.

https://www.nc3rs.org.uk/3rs-resources/housing-and-husbandry/housing-and-husbandry-dogs

You can see this in this film about dogs in research.

https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/mammals/d/domestic-dog/

https://www.britannica.com/animal/dog/Breed-specific-behaviour#ref15478

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5070630/#:~:text=Dogs%20have%20approximately%20the%20same,similar%20to%20human%20than%20mouse

http://www.animalresearch.info/en/designing-research/research-animals/dog/

Dogs in drug safety prediction: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28893587/

Virtual dog: https://nc3rs.org.uk/news/ps16m-awarded-develop-virtual-second-species

Featured news

A decade of openness on animal research

Bird flu in cows: is it a human problem?

Openness, a powerful tool to support science

Subscribe to our newsletter.

Get the latest articles and news from Understanding Animal Research in your email inbox every month. For more information, please see our privacy policy .

- Cheap and Budget Friendly Recipes

- Health Related Illness Diets

- Homemade Treat Recipes

- Homemade Dog Treats for Health Issues

- Seasonal Recipes

- Can Dogs Eat…

- Dog Diseases & Conditions

- Dog Symptoms

- Dog Grooming

- Caring For Seniors

- Dog Loss & Grieving

- Dog Reproductive Health

- Treatments and Home Remedies

- Dry Dog Food

- Wet Dog Food

- Best Dog Products

- Dog Accessories

- Dog Health Products

- CBD for Dogs

- Toy Dog Breeds

- Working Dog Breeds

- Terrier Dog Breeds

- Sporting Dog Breeds

- Non-Sporting Dog Breeds

- Mixed Breeds

- Hound Dog Breeds

- Livestock and Herding Dog Breeds

20 Most Fascinating Scientific Studies on Dogs

W e all know that dogs are amazing , but do you know just how amazing they really are? Scientists have been carrying out many different studies on dogs over the years, and they have discovered numerous fascinating and truly unbelievable things about them. The best scientific studies on dogs have proven many things about the species and their connection to humans.

Science is proving that dogs are very beneficial to our physical and mental well-being. I mean, we don't call them “man's best friend” for nothing, right? Studies have been done on the effects of dogs on humans, including children, and how they benefit us both mentally and physically .

Most of us probably don't spend a whole lot of time reading up on different canine studies done over the years. Today I'd like to share a few of the best scientific studies on dogs with you, because I think you'll be surprised at some of the findings.

Best Scientific Studies on Dogs

1. pets keep us fit.

Dog owners are much fitter because they own a dog, which makes sense if you think about it. You have to walk your dog daily to keep him happy and fit, and so you too become fitter.

A study that included 2,000 adults discovered that those who regularly walked their dog were less likely to be obese, compared with those who didn’t have a dog to walk. Older walkers can benefit too, as in another study it was found that walkers aged between 71 and 82 could walk longer and indeed faster than non dog walkers.

Read more about the study: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16459211

2. Dogs can prevent allergies and help boost your immune system

Studies have discovered that living with a dog, especially when you’re young, will prevent you from having allergies when you’re older. By having a dog, your immune system is boosted and the pet will also lower your risk of suffering from asthma and also eczema. Your immune system doesn’t need long with a dog to be boosted either – just a short amount of time is enough.

One of the best scientific studies on dogs showed that just patting a dog for 18 minutes increased saliva and raised immunoglobulin A (IgA) levels in the saliva. These raised levels mean that you have a very strong immune system.

3. Dogs reduce stress

Studies have found that owning a dog can greatly reduce your stress levels. When you have contact with a dog your stress response is lowered, and this lowers stress hormones like cortisol and your heart rate is lowered too.

Dogs can also help to lower anxiety and fear and will help to increase feelings of calmness. A study found that elderly people who walked their dogs every day had an enhanced heart rate, which is a sign of low stress levels.

Read more about the study: https://www.mja.com.au/journal/2006/184/2/effect-dog-walking-autonomic-nervous-activity-senior-citizens

4. Dogs make you more social

Studies have found that dogs make us more social, as when we walk our dogs we are out and about meeting and greeting different people. They act as icebreakers and people are far more likely to talk to you if you have a dog. One study discovered that people in wheelchairs who are with dogs received more smiles from others.

Read more about the study: https://www.health.harvard.edu/blog/pets-can-help-their-humans-create-friendships-find-social-support-201505067981

5. Dogs prevent heart attacks and strokes

Some of the best scientific studies on dogs relating to heart health have discovered that dogs can dramatically reduce your chances of having a heart attack or stroke. Dog owners have a decrease in blood pressure compared to non dog owners. Dog owners also have a reduction in cholesterol levels and also triglyceride levels.

If you have high levels of these then your chances of having a heart attack or stroke is high. Studies also found that if you have already had a heart attack or stroke you will recover faster if you have a dog.

Read more about the study: https://www.ahajournals.org/doi/full/10.1161/CIR.0b013e31829201e1

6. Dogs keep depression away

Dogs make us laugh and they make us smile, when we are with our dogs we are happier. Studies have discovered that dogs really do keep depression away.

Our dogs love us unconditionally and they need us in order to stay healthy and strong. Studies show that when we’re around dogs we feel more positive about things.

Read more about the study: https://habri.org/depression

7. Dogs keep children healthy

When children grow up with a family dog around them, they are much stronger and have stronger immune systems which will reduce the chance of them having allergies. A study carried out in 2010 showed that if you are around a dog during the first year of life you are far less likely to develop chronic skin conditions.

Read more about the study: https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2010/09/100930093229.htm

8. Dogs help children develop

When a child grows up with a dog, there are many emotional benefits as well, and the best scientific studies on dogs have proven that. The child will have someone to talk to and spend time with.

Children can express themselves better when they have a dog around them. Children also learn responsibility when they have a dog. Studies have discovered that children with autism and AHDH also benefit greatly from dog ownership.

Read more about the study: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25308197

9. Dogs help older people

Many studies have shown that an elderly person is much happier when they have a dog to look after. The dog is a great source of comfort to them and offers companionship. A dog will help to keep an elderly person connected and will greatly boost their vitality. Dogs will help to reduce the feelings of loneliness that elderly people can have.

Read more about the study: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3351901/

10. Dogs help Alzheimer’s patients

Studies have revealed that dogs really can help those suffering from Alzheimer’s disease. They show that dogs reduce behavioral issues amongst dementia patients by greatly boosting their moods. These studies also found that a patient’s nutritional intake is increased when around a dog.

Read more about the study: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4248608/

11. Dogs help against PTSD

Several studies have discovered that those suffering from PTSD are benefited greatly by the love of a dog. A dog boosts oxytocin levels in the body and can be a great help against the flashbacks that come with PTSD.

People suffering from PTSD can have angry outbursts and emotional numbness, but when around a dog this is greatly reduced. There are now many programs that team up those suffering with PTSD with dogs.

Read more about the study: https://www.mnn.com/family/pets/stories/nature-loving-pets-help-veteran-overcome-ptsd

12. Dogs can help you fight cancer

Dogs can help people suffering from cancer, and some of the best scientific studies on dogs are showing that canines ease the loneliness and depression that people with cancer can suffer from. Dogs encourage people to eat and keep up with their cancer treatment. Dogs really do try and help people recover from cancer. Canine companions benefit both adults and children that are fighting cancer.

Read more about the study: https://www.eurekalert.org/pub_releases/2015-01/tmsh-cts011315.php

13. Dogs reduce pain

Studies show that dogs can greatly reduce our pain and just 10-15 minutes with a dog is all it takes for pain to be reduced. Dogs also help improve your mood and can help with fatigue that comes with pain.

One study showed that people who had joint replacement surgery needed 28% less medication, thanks to being around a dog.

Read more about the study: https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2014/08/140807180314.htm

14. Dogs make you more attractive

Believe it or not, some of the best scientific studies on dogs show that people who own a canine are more attractive than non dog owners. They also show that women are more attracted to dog owners than non dog owners. So, if you’re out to impress, a dog will work wonders.

Read more about the study: https://www.slate.com/articles/health_and_science/science/2014/02/

15. Dogs help to strengthen bonds

Studies show that those who have a strong bond with their dog also have greater bonds with other people. One study involved 500 people aged between 18 and 26 and discovered that the ones that owned dogs had a closer bond with others.

Read more about the study: https://www.huffingtonpost.com/2014/02/03/pet-social-connectedness-young-adult_n_4703790.html

16. Dogs can detect cancer

A few of the best scientific studies on dogs have revealed that some dogs can literally sniff out cancer and could save your life. One dog named Marnie who is an eight year old black Labrador sniffed out cancer 91% of the time just by sniffing breath.

Marnie also showed that she can detect colorectal cancer 97% of the time by sniffing stools.

Read more about the study: https://abcnews.go.com/Health/CancerPreventionAndTreatment/dog-detects-colorectal-cancer-standard-screening-test/story?id=12805641

17. Dogs can detect food that you’re allergic to

Your dog knows exactly what you’re allergic to studies can reveal, and can smell just the hint of peanut butter. Peanut detecting dogs really can help to save the lives for those with peanut allergies.

Read more about the study: https://www.livescience.com/35463-seven-surprising-health-benefits-dog-ownership-110209.html

18. Dogs make us happy

A study in 2009 showed that our oxytocin levels were dramatically raised when we are in contact with a dog.

The study found that those who looked into a dog’s eye the longest had the highest readings of oxytoxin. No wonder we’re always happy when we’re with our best firends.

Read more about the study: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19124024

19. Dogs bring out the caretaker in us

It has been found that just by looking at a dog’s face they can bring out the caretaker in us. Their large eyes, floppy ears and cute features make us feel that we have to take good care of them. We have the same reaction when we’re around infants.

Read more about the study: https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0058248

20. Dogs boost self esteem

When you have the responsibility of caring for your dog you feel so much better about yourself. You have someone to care for who loves you unconditionally and you have to do your very best for them.

When you have a dog to care for your whole outlook on life changes and you get to meet and greet new people as you’re walking your dog, resulting in higher self esteem.

Read more about the study: https://psycnet.apa.org/psycinfo/2011-13783-001/

LATEST FEATURES

4 Tips & Tricks for Navigating Peak Flea and Tick Season

Can I Afford A Dog?

How to Get Rid of a Dog: The Right Way

Why Are Dogs So Loyal?

Why Do Pets Make Us Happy?

Dog Names Starting With Z

How Many Dogs Are Too Many?

Can Dogs Get Sick From Humans?

Dandie Dinmont Terrier Breed Profile

Dog Names Starting With Y

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- No AI Clause

May 6, 2024

Puppy-Dog Eyes in Wild Canines Spark Rethink on Dog Evolution

The eyebrows of the African wild dog have scientists wondering whether other canine species besides domestic dogs can make the irresistible “puppy-dog eyes” expression

By Gillian Dohrn & Nature magazine

A pack of African wild dogs ( Lycaon pictus ) warily approaches a remote camera near banks of Moremi River in Botswana.

Paul Souders/Getty Images

“Puppy-dog eyes didn’t just evolve for us, in domestic dogs,” says comparative anatomist Heather Smith. Her team’s work has thrown a 2019 finding that the muscles in dogs’ eyebrows evolved to communicate with humans in the doghouse by showing that African wild dogs also have the muscles to make the infamous pleading expression. The study was published on 10 April in The Anatomical Record .

Now, one of the researchers who described the evolution of puppy-dog eyebrow muscles is considering what the African dog discovery means for canine evolution. “It opens a door to thinking about where dogs come from, and what they are,” says Anne Burrows, a biological anthropologist at the Duquesne University in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and author of the earlier paper.

Evolution of canine eyebrows

On supporting science journalism.

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing . By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The 2019 study garnered headlines around the world when it found that the two muscles responsible for creating the sad–sweet puppy-dog stare are pronounced in several domestic breeds ( Canis familiaris ), but almost absent in wolves ( Canis lupus ).

If the social dynamic between humans and dogs drove eyebrow evolution, Smith wondered whether the highly social African wild dog might also have expressive brows.

African wild dogs ( Lycaon pictus ) are native to sub-Saharan Africa. Between 1997 and 2012, their numbers dropped by half in some areas. With only 8,000 or so remaining in the wild, studying them is difficult but crucial for conservation efforts.

Smith, who is based at Midwestern University in Glendale, Arizona, and her colleagues dissected a recently deceased African wild dog from Phoenix Zoo. They found that both the levator anguli oculi medalis (LAOM) and the retractor anguli oculi lateralis (RAOL) muscles, credited with creating the puppy-dog expression, were similar in size to those of domestic dog breeds.

“We could see distinct fibres that are very prominent, very robust,” says Smith. Although the researchers only looked at one African wild dog, Smith says it’s unlikely that such a large and well-developed muscle would be present in one animal and not others.

A communication strategy

The team proposes that the gregarious African wild dogs evolved these muscles to communicate with each other. They use a range of vocal cues to organize hunts and share resources, but until now, non-vocal strategies haven’t been studied.

Burrows speculates that more dog species might have muscles for facial expression than the researchers realized when they compared wolves and domestic dogs. “I wonder if these muscles have been around for a really long time and wolves are the ones that lost them.”

Muhammad Spocter, an anatomist at Des Moines University in West Des Moines, Iowa, says the study is exciting, but cautions against making assumptions about wild dog behaviour based on their physical structure. “Just because the anatomy is there, is it being used?” says Spocter. “And how is it being used?”

This article is reproduced with permission and was first published on May 5, 2024 .

- DIGITAL MAGAZINE

MOST POPULAR

10 awesome dog facts!

Get the lowdown on these adorable animals….

Ready to learn some paw- some dog facts? Then you’re in the right place! Join National Geographic Kids as we get the lowdown on our fur -tastic friends…

1. Dogs are the most popular pet on the planet!

A third of ALL households around the world have a dog. These playful, friendly, loyal animals make great companions , but they can also be fierce and tough protectors , or intelligent helpers .

2. They evolved from a now-extinct species of wolf.

Dogs were the first animal domesticated (tamed) by humans, over 20,000 years ago! As they evolved from wolves , their skulls, teeth and paws shrank , and they became more docile and obedient .

FUN FACT! Evidence from fossils suggests that five types of dog had evolved by the Bronze Age , around 4500BC. These were mastiffs , wolf-type dogs, dogs similar to greyhounds, pointing dogs and herding dogs. Bow wow!

3. They can learn over 100 words and gestures!

Dogs are thought to be as smart as two-year-old children (and much easier to train!), so many owners teach them commands and tricks .

4. Dog noses are at least 40x more sensitive than ours!

These clever canines have an incredible sense of smell – allowing them to follow scent trails days after they were left. Amazingly, bloodhounds ‘ sense of smell is so spot on that it can be used as evidence in court!

FUN FACT! Dogs also have fantastic hearing! They can detect high-pitched noises and spot sounds from much further away than humans can.

5. Many work as assistance dogs, helping humans!

Many dogs are trained to work as guide dogs , helping blind people get around safely. Others are assistance dogs , who keep their owners calm and safe , while some brave hounds are search and rescue dogs , who help human rescuers save people from danger.

WEIRD BUT TRUE! Some working dogs are trained to use their super senses to sniff out explosives and illegal goods , or alert humans to potentially dangerous health issues . Wow!

6. They only sweat from their paws, and have to cool down by panting.

The sweat is much oilier than humans’, and it contains lots of chemicals that only other dogs can detect. Weirdly, it also makes many dog paws smell of cheesy crisps !

7. They can be right or left-pawed!

Like humans, most dogs have a dominant hand – or in their case, paw! To figure out which one it is, you can conduct a simple science experiment …

Watch a dog moving from standing still to walking forwards. Do they start walking with their left leg, or their right? Watch several times, noting down the starting leg each time, and see if there’s a pattern . Many dogs will often lead with the same leg – their dominant one!

8. The Ancient Egyptians saw dogs as god-like !

Ancient breeds like the Saluki lived in the lavish palaces of Egyptian royalty ! The pampered pooches had their own servants , were decked out in jewelled collars , and ate only the finest meats .

WEIRD BUT TRUE! Dead rulers were often buried with their doggy pals, as they believed the hounds would protect them from harm in the afterlife.

9. Dogs use body language to express their feelings.

From their ears to their eyebrows , shoulders , and tail , dogs often use signals and smells , rather than sound , to communicate! Their posture makes a big difference, too.

Next time you see a dog interacting with a person or other dog, pay close attention. Are they shrinking themselves down small, or standing up big and tall? What do you think they’re trying to say ?

10. Owning a dog is a BIG responsibility!

Just like humans, dogs have feelings and needs , and they have to be taken care of properly. They need regular walking , healthy food , a clean, cosy place to sleep and lots and lots of love and affection ! Make sure you and your family think carefully before you get a dog (or any pet!) to make sure you have the time and means to take one on.

What did you think of our awesome dog facts? Let us know by leaving a comment, below!

Leave a comment.

Your comment will be checked and approved shortly.

WELL DONE, YOUR COMMENT HAS BEEN ADDED!

GREAT READ THANKS

I love dogs I think there amazing animals!

Thanks for the cool magazine NatGeoKids! They’re the best!!!

This is so amazing. I love Dogs

i am a big fan of dogs

I love dogs, they are the coolest living thing on earth

pretty good it does tell a lot of good facts about dog's and i like the pitcher's and time put in it! And i think other kids might like it like me!

My favirote fact is the trick to see what there domnante paw is defently going to try it with my dog.

When my dog is curious or hears something his ears always go up and forward.

CUSTOMIZE YOUR AVATAR

More like general animals.

10 hopping fun rabbit facts!

Hedgehog Facts!

10 terrific tiger facts!

Rhino facts!

Sign up to our newsletter

Get uplifting news, exclusive offers, inspiring stories and activities to help you and your family explore and learn delivered straight to your inbox.

You will receive our UK newsletter. Change region

WHERE DO YOU LIVE?

COUNTRY * Australia Ireland New Zealand United Kingdom Other

By entering your email address you agree to our Terms of Use and Privacy Policy and will receive emails from us about news, offers, activities and partner offers.

You're all signed up! Back to subscription site

Type whatever you want to search

More Results

You’re leaving natgeokids.com to visit another website!

Ask a parent or guardian to check it out first and remember to stay safe online.

You're leaving our kids' pages to visit a page for grown-ups!

Be sure to check if your parent or guardian is okay with this first.

- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Perspective article, the new era of canine science: reshaping our relationships with dogs.

- 1 School of Anthropology, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, United States

- 2 College of Veterinary Medicine, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, United States

- 3 Cognitive Science, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, United States

- 4 California State Polytechnic University, Pomona, CA, United States

- 5 Department of Psychology, Western Carolina University, Cullowhee, NC, United States

- 6 Center for Urban Resilience, Loyola Marymount University, Los Angeles, CA, United States

- 7 Animal Welfare Science Centre, Faculty of Veterinary and Agricultural Sciences, The University of Melbourne, Melbourne, VIC, Australia

Canine science is rapidly maturing into an interdisciplinary and highly impactful field with great potential for both basic and translational research. The articles in this Frontiers Research Topic, Our Canine Connection: The History, Benefits and Future of Human-Dog Interactions , arise from two meetings sponsored by the Wallis Annenberg PetSpace Leadership Institute, which convened experts from diverse areas of canine science to assess the state of the field and challenges and opportunities for its future. In this final Perspective paper, we identify a set of overarching themes that will be critical for a productive and sustainable future in canine science. We explore the roles of dog welfare, science communication, and research funding, with an emphasis on developing approaches that benefit people and dogs, alike.

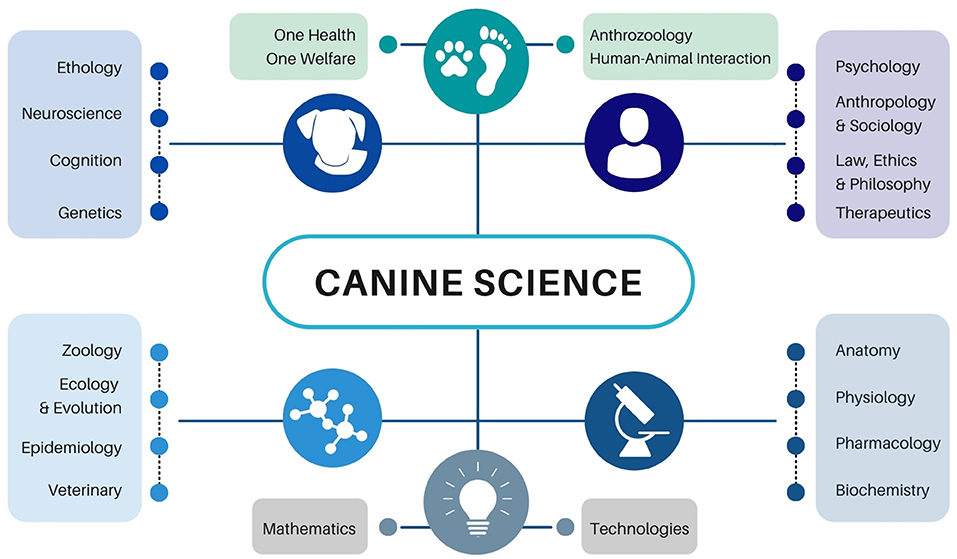

Dogs have played important roles in the lives of humans for millennia ( 1 , 2 ). However, throughout much of scientific history they have been dismissed as an artificial species with little to contribute to our understanding of the natural world, or our place within it. During the last two decades, this sentiment has changed dramatically; canine science is rapidly maturing into an established, impactful, and highly interdisciplinary field ( Figure 1 ). Canine scientists, who previously occupied relatively marginalized roles in academic research, are increasingly being hired at major research universities, and centers devoted to the study of dogs and their interactions with humans are proliferating around the world. The factors underlying dogs' newfound popularity in science are diverse and include (1) increased interest in understanding dog origins, behavior, and cognition; (2) diversification in our approaches to research with non-human animals; (3) recognition of dogs' value as a unique biological model with relevance for humans; and (4) growth in research on the nature and consequences of dog-human interactions, in their myriad forms, from working dog performance to displaced canines living in shelters.

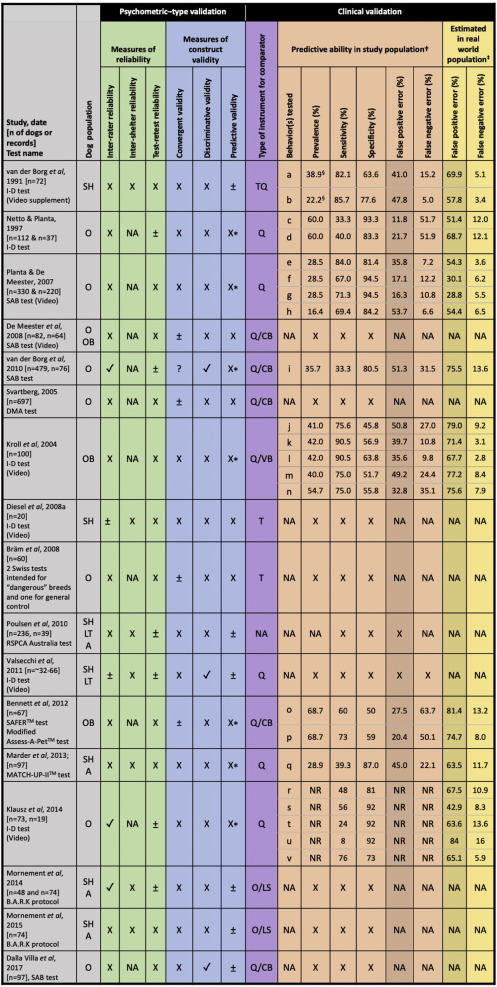

Figure 1 . Canine science is an interdisciplinary field with connections to other traditional and emerging areas of research. The specific fields shown overlap in ways not depicted here and are not an exhaustive list of disciplines contributing to canine science. Rather, they are included as examples of the diversity of scholarship in canine science.

This Perspective represents the final article in a collection of manuscripts arising from two workshops sponsored by the Wallis Annenberg PetSpace Leadership Institute. Leadership Fellows from around the world gathered in 2017 and 2020 to discuss the state of research and future directions in canine science. The individual articles in this collection provide a detailed treatment of key topics discussed at these events. In this final article, we identify a set of overarching challenges that emerge from this work and identify priorities and opportunities for the future of canine science.

The rise of canine science has benefited substantially from public interest and participation in the research process. Unlike many research studies, which unfold quietly in the ivory towers of research universities, the new era of canine science is intentionally public facing. The dogs being studied are not laboratory animals, bred and housed for research purposes, but rather are companions living in private homes, or assisting humans in capacities ranging from assistance for people with disabilities, to medical and explosives detection. Campus-based research laboratories have opened their doors to members of the public who bring their dogs to participate in problem-solving tasks, social interactions, and sometimes even non-invasive neuroimaging studies. Increasingly, dog owners themselves play a significant role in the scientific process, serving as community scientists who contribute to the systematic gathering of data from the convenience of their homes.

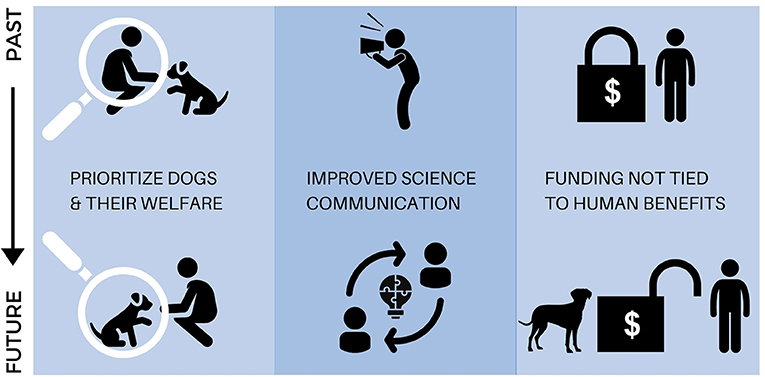

This new research model in conjunction with emerging technologies, makes canine science a highly visible field that engages public stakeholders in unprecedented ways. From a scientific perspective, society has become the new laboratory, and in doing so, has facilitated research with dogs of a scope and scale that was heretofore unthinkable. As tens of thousands of dogs contribute to research on topics ranging from cognition and genetics ( 3 , 4 ) to aging and human loneliness ( 5 ), canine science is entering the realm of “big data” and eclipsing many traditional research approaches. Importantly, these advances are occurring simultaneously across diverse fields of science, creating powerful new opportunities for consilience that will make canine science even more valuable in the years ahead. However, maturing this model toward a sustainable future that serves its diverse stakeholders—who include scientists, research funders, members of the public, and dogs themselves—will require careful navigation of key challenges related to dog welfare, science communication, and financial support ( Figure 2 ).

Figure 2 . Visual summary of the key issues identified in this Perspective . A sustainable future in canine science will require (1) research approaches that prioritize and monitor the welfare of dogs, (2) improved science communication to avoid incorrect reporting of study results, and to translate research findings to meaningful change in practices relating to dogs, and (3) availability of research funding that is not tied exclusively to studying the possible benefits of dogs for humans.

Dog Welfare

Globally, animal welfare has been linked to the public acceptability that underpins sustainable animal interactions and partnerships ( 6 ). Where human-animal interactions have failed to meet community expectations, practices and in some case entire industries, have been disrupted or ceased. Recent examples include whaling for profit and greyhound racing ( 6 , 7 ). Science is not exempt from this necessity to meet with public expectations and the new era of canine science must place canine welfare at the forefront. Considering dogs as individuals and co-workers, rather than tools for work or subjects, reflects a community moral and ethical paradigm shift that is currently underway. Reimagining our relationship with domestic dogs in research will also help inform our treatment of other animals. In this way, studies of dogs and our interactions with them can serve as a pioneering new model for many areas of science.

As scientists advocate for the revision of community and industry practices with dogs in light of new evidence, we must apply the same criteria to the conduct of our research. This includes adjusting canine research and training methods to acknowledge the sentience of dogs, and the importance of the affective experience for dogs in both research and community settings ( 8 – 11 ). The discipline of animal welfare science has progressed rapidly over the last two decades, and we have many animal-based, welfare-outcome measures available to us ( 6 , 11 ). Ensuring the well-being of the dogs we study will be as critical to ongoing social license to operate (i.e., community approval) for canine science as it is for working dog interests ( 12 ). Being transparent about the issues of animal consent and vulnerability, as well as offering animals agency with regard to their participation in science are valuable suggestions offered within this special issue. We encourage our colleagues to not just consider this paradigm shift, but to effect it through prioritizing and representing the dog's perspective and welfare in their research.

Although increasingly, researchers may include a single or limited set of canine stress measures in studies exploring dogs' potential benefits to humans, this approach alone does not fill the need for studies that prioritize an understanding of canine welfare as their central focus. Canine welfare should be considered not just as an emergent population-level measure ( 13 ) but rather with respect to the way in which it is experienced: from the perspectives of individual dogs. Commonly used statistical methods from human research, such as group-based trajectory analysis ( 14 ) may offer proven techniques that allow meaningful reporting on populations while reflecting the nuance of shared, sub-group patterns. Such approaches will better reflect individual differences, for example variations in canine personality, social support and relationship styles, as well as other significant factors. One impediment to robust measurement of animal welfare in canine science has been limited funding.

We believe that all granting bodies who fund exploration of the possible benefits to people from dogs should also fund and require the canine perspective to be robustly monitored and reported. Impediments to this work arise not from lack of researcher interest or access to dogs, but rather from challenges to securing funding that is independent from a focus on human health outcomes, or other tangible outcomes of work that dogs perform. To be able to optimize canine welfare, there is an urgent need for increased funding specifically to study the welfare of dogs, in all their diversity. The new era of canine science will identify what dogs need to thrive, propelling us toward a mutually sustainable partnership between people and dogs.

Communication