- Staff Directory

- Workshops and Events

- For Students

Literature Review: Academic Dishonesty – What Causes It, How to Prevent It

by Thomas Keith | Nov 16, 2018 | Instructional design

Note: For further information on academic dishonesty and academic integrity, please see our series Combating Academic Dishonesty . Part 1 | Part 2 | Part 3

Academic dishonesty, which encompasses behaviors such as cheating, plagiarism, and falsification of data or citations, is a widespread and troubling phenomenon in higher education. (For the full spectrum of behaviors that qualify as academic dishonesty, see Berkeley City College’s What Is Academic Dishonesty? ) It may be as simple as looking over a classmate’s shoulder during a quiz or as elaborate as hiring a ghostwriter online for a course paper, but whatever the method employed, academic dishonesty harms the learning experience and gives cheaters an unfair advantage over those who abide by the rules. This post examines some of the chief factors that lead to academic dishonesty among college students, as determined by empirical research in the field, and offers suggestions to faculty and instructors on ways to reduce the likelihood of dishonest conduct among their students.

What Causes Academic Dishonesty?

There is no single explanation for the occurrence of dishonest behavior in college. Studies suggest that most students realize academic dishonesty is morally wrong, but various outside factors or pressures may serve as “neutralizers,” allowing students to suppress their feelings of guilt and justify their dishonest acts to themselves (Baird 1980; Haines et al. 1986; Hughes and McCabe 2006). In certain cases, dishonest behavior may arise not from willful disregard for the rules of academic integrity, but from ignorance of what those rules are. Some common reasons for students’ engaging in academic dishonesty are given below.

Poor time management

Particularly in their early years of college, many students have difficulties with managing their time successfully. Faced with demands on their out-of-class time from athletics, extracurricular clubs, fraternities and sororities, etc., they may put off studying or working on assignments until it is too late for them to do a satisfactory job. Cheating then appears attractive as a way to avoid failure (Haines et al. 1986).

Academic pressures

Sometimes a student must maintain a certain GPA in order to receive merit-based financial aid, to participate in athletics, or even to continue receiving financial support from his/her family. Even high-achieving students may turn to academic dishonesty as a way to achieve their target GPA. Academic pressures can be worsened in courses that are graded on a curve: with the knowledge that only a fixed number of As can be awarded, students may turn to dishonest methods of surpassing their classmates (Whitley 1998; Carnegie Mellon University ).

In very large classes, students may feel anonymous; if the bulk of their interaction is with teaching assistants, they may regard the instructor as distant and unconcerned with their performance. This can increase the temptation to cheat, as students rationalize their dishonest behavior by assuming that the instructor “doesn’t care” what they do. Not surprisingly, this can often be a danger in online courses, since course sizes can be huge and students do not normally interact with their instructors face-to-face ( Carnegie Mellon University ).

Failure to understand academic conventions

The “rules” of academic writing often appear puzzling to students, particularly those who have not had extensive practice with academic writing in high school. The Internet has arguably exacerbated this problem; the easy availability of information (accurate or otherwise) on websites has led many students to assume that all information sources are de facto public property and need not be cited, which leads to unintentional plagiarism. Faculty and instructors should not take for granted that their students simply “know” when they must cite sources and how they should do so (Perry 2008). In addition, the ready availability of websites on every topic imaginable has had a deleterious effect on students’ ability to assess sources critically. Some students simply rely upon whichever site comes up at the top of a Google search, without considering the accuracy or potential biases of the information with which they are being presented.

Cultural factors

Related to the above, international students may face particular challenges in mastering the conventions of academic writing. They do not necessarily share Western/American understandings of what constitutes “originality,” intellectual property rights, and so forth, and it often takes time and practice for them to internalize the “rules” fully, especially if English is not their first language. In addition, students who come from cultures where collaborative work is common may not realize that certain assignments require them to work entirely on their own (Currie 1998; Pecorari 2003; Hughes and McCabe 2006; Abasi and Graves 2008).

The academic pressures common to all college students can be particularly acute for international students. In some cultures (e.g. those of East Asia) excellent academic performance at the university level is vital for securing good jobs after graduation, and students may therefore believe that their futures depend upon receiving the highest possible grades. When a student’s family is making sacrifices to send him/her overseas for college, s/he may be concerned about “letting the family down” by doing poorly in school, which can make academic dishonesty all the more tempting.

Low-Stakes Assignments

While some people may think of cheating as a risk only on high-stakes assignments (course papers, final exams, and the like), it can easily occur on low-stakes assignments as well. In fact, the very lack of grade weight that such assignments bear can encourage dishonesty: students may conclude that since an assignment has little or no bearing on their course grade, it “doesn’t matter” whether or not they approach it honestly. For this reason, it is vital to stress to students the importance of honest conduct on all assignments, whether big or small. The University does not take grade weight into account when deciding whether academic dishonesty has occurred; plagiarism is plagiarism and cheating is cheating, even if the assignment in question is worth zero points.

Technology and Academic Dishonesty

The rapidly increasing sophistication of digital technology has opened up new avenues for students bent on academic dishonesty. Beyond simply cutting-and-pasting from webpages, an entire Internet economy has sprung up that offers essays for students to purchase and pass off as their own. Students may also use wireless technology such as Bluetooth to share answers during exams, take pictures of exams with their smartphones, and the like (McMurtry 2001; Jones, Reid, and Bartlett 2008; Curran, Middleton, and Doherty 2011). Research suggests that the use of technology creates a “distancing” effect that makes students’ guilt about cheating less acute ( Vanderbilt University ).

How Can Faculty and Instructors Combat Academic Dishonesty?

There is no panacea to prevent all forms of dishonest behavior. That said, at each step of the learning design process, there are steps that faculty and instructors can take to help reduce the likelihood of academic dishonesty, whether by making it more difficult or by giving students added incentive to do their work honestly.

Course Management and Syllabus Design

The sooner students are informed about the standards of conduct they should adhere to, the greater the likelihood that they will internalize those standards (Perry 2010). This is why it is worthwhile for faculty to devote a portion of their syllabus to setting standards for academic integrity. Consider setting the tone for your course by offering a clear definition of what constitutes academic dishonesty, the procedure you will follow if you suspect that dishonest behavior has occurred, and the penalties culprits may face. Include a link to UChicago’s statement on Academic Honesty and Plagiarism . If you have a Canvas course site, you can create an introductory module where students must read a page containing your academic integrity policies and “mark as done,” or take a quiz on your policies and score 100%, in order to receive credit for completing the module.

If your syllabus includes many collaborative assignments, it can also be useful to explain clearly for which assignments collaboration is permitted and which must be done individually. You can also specify what you consider acceptable vs. unacceptable forms of collaboration (e.g. sharing ideas while brainstorming is allowed, but copying one another’s exact words is not).

Finally, consider including information in your syllabus about resources available to students who are having academic difficulties, such as office hours and tutoring. Students who are facing difficulties with time management, executive function, and similar issues may benefit from the Student Counseling Service’s Academic Skills Assessment Program (ASAP) . The University’s Writing Center offers help with mastering academic writing and its conventions. Encourage your students to avail themselves of these resources as soon as they encounter difficulties. If they get help early on, they will be less likely to feel desperate later and resort to dishonest behavior to raise their grade (Whitley 1998).

In general, making your expectations clear at the outset of your course helps to build a strong relationship between you and your students. Your students will feel more comfortable coming to you for help, and they will also understand the risks they would be running if they behaved dishonestly in your course, which can be a powerful deterrent.

Assignment Design

When crafting assignments such as essays and course papers, strive for two factors: originality and specificity. The more original the topic you choose, and the more specific your instructions, the less likely it is that students will be able to find a pre-written paper on the Internet that fits all the requirements (McMurtry 2001). Changing paper topics from year to year also avoids the danger that students may pass off papers from previous years as their own work. You might consider using a rubric with a detailed breakdown of the factors you will be assessing in grading the assignment; Canvas offers built-in rubric functionality .

If an assignment makes up a large percentage of your students’ final grade (e.g. a course paper), you might consider using “scaffolding”. Have the students work up to the final submission through smaller, lower-stakes sub-assignments, such as successive drafts or mini-papers. This has the double benefit of making it harder for students to cheat (since you will have seen their writing process) and reducing their incentive to cheat (since their grade will not be solely dependent upon the final submission) ( Carnegie Mellon University ).

In the case of in-class exams, you may find it worthwhile to create multiple versions of an exam, each with a separate answer key. Even as simple an expedient as placing the questions in a different order in different versions makes it harder for students to copy off one another’s work or share answer keys ( Carnegie Mellon University ).

Technological Tools to Prevent Academic Dishonesty

Even as students have discovered more sophisticated ways to cheat, educational professionals and software developers have created new technologies to thwart would-be cheaters. Canvas, the University’s learning management system, includes several features intended to make cheating more difficult.

By default, the Files tab in Canvas is turned off when a new course is created. This prevents students from accessing your course files and viewing files they should not, such as answer keys or upcoming exam questions. If you choose to enable Files in your course, you should place all sensitive files in locked or unpublished folders to render them invisible to students. For more details, see this post .

If you are using Canvas Quizzes in your course, you can choose from a number of options that increase the variation between individual students’ Quizzes and thus decrease the chances of cheating. These including randomizing answers for multiple-choice questions; drawing randomly selected questions from question groups; and setting up variables in mathematical questions, so that different students will see different numerical values. For more details, see this post .

Several different computer programs have been developed that claim to detect plagiarism in student papers, usually by comparing student submissions against the Internet, a database of past work, or both, and then identifying words and phrases that match. Viper follows a “freemium” model, while the best-known subscription-based plagiarism checker, Turnitin , is currently licensed only by the Law School at the University of Chicago. These programs can be helpful, but bear in mind that no automatic plagiarism checker is 100% accurate; you will still need to review student work yourself to see whether an apparent match flagged by the software is genuine plagiarism or not (Jones, Reid, and Bartlett 2008). Also be aware that Turnitin and some other plagiarism checkers assert ownership rights over student work submitted to them, which can raise issues of intellectual property rights.

In addition to detecting plagiarism after the fact, there are technological tools that can help prevent it from occurring in the first place. Citation managers such as Endnote and Zotero are excellent ways to help students manage their research sources and cite them properly, especially when writing longer papers that draw on a wide range of source material. The University of Chicago Library offers a detailed guide to citation managers , along with regular workshops on how to use them .

What to Do if You Suspect Academic Dishonesty

If you suspect that academic dishonesty may have occurred in one of your courses, the University has resources to which you can turn. For undergraduates, it is best to begin by speaking to the student’s academic adviser . You can find out which adviser is assigned to a student in your course by visiting Faculty Access and looking at the “Advisor” column in the course roster. If you have questions about disciplinary procedures specific to the College, you can contact the Office of College Community Standards, headed by Assistant Dean of Students Stephen Scott . For graduate students, the appropriate area Dean of Students can provide information about the correct disciplinary procedures to follow.

The fight against academic dishonesty is a difficult one, and will continue to be so for the foreseeable future. But if faculty and instructors give careful thought to the causes of student misconduct and plan their instructional strategies accordingly, they can do much to curb dishonest behavior and ensure that integrity prevails in the classroom.

Bibliography

Journal articles.

- Abasi, Ali R., and Barbara Graves. “Academic Literacy and Plagiarism: Conversations with International Graduate Students and Disciplinary Professors.” Journal of English for Academic Purposes 7.4 (Oct. 2008), 221-233.

- Baird, John S., Jr. “Current Trends in College Cheating.” Psychology in the Schools 17 (1980), 515-522.

- Curran, Kevin, Gary Middleton, and Ciaran Doherty. “Cheating in Exams with Technology.” International Journal of Cyber Ethics in Education 1.2 (Apr.-Jun. 2011), 54-62.

- Currie, Pat. “Staying Out of Trouble: Apparent Plagiarism and Academic Survival.” Journal of Second Language Writing 7.1 (Jan. 1998), 1-18.

- Haines, Valerie J., et al. “College Cheating: Immaturity, Lack of Commitment, and the Neutralizing Attitude.” Research in Higher Education 25.4 (Dec. 1986), 342-354.

- Hughes, Julia M. Christensen, and Donald L. McCabe. “Understanding Academic Misconduct.” Canadian Journal of Higher Education 36.1 (2006), 49-63.

- Jones, Karl O., Juliet Reid, and Rebecca Bartlett. “Cyber Cheating in an Information Technology Age.” In R. Comas and J. Sureda (coords.). “Academic Cyberplagiarism” [online dossier]. Digithum: The Humanities in the Digital Era 10 (2008), n.p. UOC. [Accessed: 26/09/18] ISSN 1575-2275.

- McMurtry, Kim. “E-Cheating: Combating a 21st Century Challenge.” Technological Horizons in Education Journal 29.4 (Nov. 2001), 36-40.

- Pecorari, Diane. “Good and original: Plagiarism and patchwriting in academic second-language writing.” Journal of Second Language Writing 12.4 (Dec. 2003), 317-345.

- Perry, Bob. “Exploring Academic Misconduct: Some Insights into Student Behaviour.” Active Learning in Higher Education 11.2 (2010), 97-108.

- Whitley, Bernard E. “Factors Associated with Cheating among College Students: A Review.” Research in Higher Education 39.3 (Jun. 1998), 235-274.

Web Resources

- Berkeley City College: http://www.berkeleycitycollege.edu/wp/de/what-is-academic-dishonesty/

- Carnegie Mellon University: https://www.cmu.edu/teaching/solveproblem/strat-cheating/index.html

- University of Chicago: https://college.uchicago.edu/advising/academic-honesty | https://studentmanual.uchicago.edu/Policies

- Colorado State University: https://tilt.colostate.edu/integrity/resourcesFaculty/whyDoStudents.cfm

- Harvard University (Zachary Goldman): https://www.gse.harvard.edu/uk/blog/youth-perspective

- Oakland University: https://www.oakland.edu/Assets/upload/docs/OUWC/Presentations%26Workshops/dont_fail_your_courses.pdf

- Vanderbilt University (Derek Bruff): https://cft.vanderbilt.edu/2011/02/why-do-students-cheat/

Search Blog

Subscribe by email.

Please, insert a valid email.

Thank you, your email will be added to the mailing list once you click on the link in the confirmation email.

Spam protection has stopped this request. Please contact site owner for help.

This form is protected by reCAPTCHA and the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Recent Posts

- Evaluate Different Lenses for Looking at AI in Teaching – Part Two

- Digital Tools and Critical Pedagogy: Design Your Course Materials with Neurodivergence in Mind

- Evaluate Different Lenses for Looking at AI in Teaching: Part One

- Improve Your Videos’ Accessibility with New Panopto Updates

- Optimize Your Canvas Course Structure for Seamless Navigation

- A/V Equipment

- Accessibility

- Canvas Features/Functions

- Digital Accessibility

- Faculty Success Stories

- Instructional design

- Multimedia Development

- Surveys and Feedback

- Symposium for Teaching with Technology

- Uncategorized

- Universal Design for Learning

- Visualization

Click through the PLOS taxonomy to find articles in your field.

For more information about PLOS Subject Areas, click here .

Loading metrics

Open Access

Peer-reviewed

Research Article

Academic dishonesty among university students: The roles of the psychopathy, motivation, and self-efficacy

Roles Conceptualization, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

* E-mail: [email protected]

Affiliation Institute of Psychology, University of Silesia in Katowice, Katowice, Poland

Roles Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing

Affiliations Department of General Psychology, University of Padua, Padua, Italy, Institute of Psychology, Cardinal Stefan Wyszyński University in Warsaw, Warsaw, Poland

- Lidia Baran,

- Peter K. Jonason

- Published: August 31, 2020

- https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0238141

- Reader Comments

Academic dishonesty is a common problem at universities around the world, leading to undesirable consequences for both students and the education system. To effectively address this problem, it is necessary to identify specific predispositions that promote cheating. In Polish undergraduate students ( N = 390), we examined the role of psychopathy, achievement goals, and self-efficacy as predictors of academic dishonesty. We found that the disinhibition aspect of psychopathy and mastery-goal orientation predicted the frequency of students’ academic dishonesty and mastery-goal orientation mediated the relationship between the disinhibition and meanness aspects of psychopathy and dishonesty. Furthermore, general self-efficacy moderated the indirect effect of disinhibition on academic dishonesty through mastery-goal orientation. The practical implications of the study include the identification of risk factors and potential mechanisms leading to students’ dishonest behavior that can be used to plan personalized interventions to prevent or deal with academic dishonesty.

Citation: Baran L, Jonason PK (2020) Academic dishonesty among university students: The roles of the psychopathy, motivation, and self-efficacy. PLoS ONE 15(8): e0238141. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0238141

Editor: Angel Blanch, University of Lleida, SPAIN

Received: April 9, 2020; Accepted: August 10, 2020; Published: August 31, 2020

Copyright: © 2020 Baran, Jonason. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Data Availability: The database was uploaded to Open Science Framework and is available under the following address: https://osf.io/frq9v/ .

Funding: Funding was provided by the Polish National Agency for Academic Exchange ( https://nawa.gov.pl/en/ ) to P.K.J under Grant number PPN/ULM/2019/1/00019/U/00001. This funding source had no role in the study conception, design, analysis, interpretation, or decision to submit for publication.

Competing interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Introduction

Academic dishonesty refers to behaviors aimed at giving or receiving information from others, using unauthorized materials, and circumventing the sanctioned assessment process in an academic context [ 1 ]. The frequency of academic dishonesty reported in research indicates the global nature of this phenomenon. For example, in a study by Ternes, Babin, Woodworth, and Stephens [ 2 ] 57.3% of post-secondary students in Canada allowed another student to copy their work. Similarly, 61% of undergraduate students in Sweden copied material for coursework from a book or other publication without acknowledging the source [ 3 ]. Working together on an assignment when it should be completed as an individual was reported by 53% of students from four different Australian universities [ 4 ], and copying from someone’s paper in exams at least once was done by 36% of students from four German universities [ 5 ]. Research shows that academic dishonesty is also a major problem at Polish universities. In the study by Lupton, Chapman, and Weiss [ 6 ] 59% of the students admitted to cheating in the current class, and 83.7% to cheating at some point during college. According to a report on the plagiarism in Poland, prepared by IPPHEAE Project Consortium, 31% of students reported plagiarizing accidentally or deliberately during their studies [ 7 ].

Existing academic dishonesty prevention systems include using punishments and supervision [ 8 ], informing students about differences between honest and dishonest academic actions [ 9 ], adopting university honor codes [ 10 ], and educating students on how to write papers and conduct research correctly [ 11 ]. Although these methods lead to a reduction of academic dishonesty (see [ 12 ]), their problematic aspects include the possibility of achieving only a temporary change in behavior, limited impact on students' attitudes towards cheating, and a long implementation period [ 13 , 14 ]. Possible reasons for these difficulties include the fact that conventional prevention methods rarely address differences in students’ personality and academic motivations, which may be associated with a tendency to cheat. For example, previous studies have reported that negative emotionality was associated with positive attitudes toward plagiarism [ 15 ]; intrinsic motivation was associated with lower self-reported cheating [ 16 ]; and socially orientated human values were negatively, while personally focused values were positively correlated with academic dishonesty [ 17 ].

It is also important to remember that implementing the aforementioned methods of prevention will not lead to a reduction in academic dishonesty if faculty members do not follow and apply the established rules [ 18 ]. Faculty members often prefer not to take formal actions against dishonest students [ 19 ], and in many cases do not use the methods available to them to detect and prevent cheating [ 20 ]. However, when they do respond to academic dishonesty it is often in inconsistent ways [ 21 ]. This might suggest that, while dealing with students’ dishonesty, faculty members prefer to choose their own punitive and preventative methods, which may differ depending on the particular student and professor. If that is the case, then examining the role of individual differences in academic dishonesty could be useful not only to better understand the nature of academic transgressions but also to address faculty's informal ways of dealing with students' cheating.

The aim of the current study was to investigate relationships between personality, motivation, and academic dishonesty to understand the likelihood of cheating in academia more effectively and potentially inform faculty's personalized interventions. Of all the personality traits under investigation, psychopathy appears to be useful for this purpose, because it includes a tendency to be impulsive, to engage in sensation-seeking, and resistance to stress, all of which are associated with academic dishonesty [ 2 ]. Indeed, psychopathy is the strongest—albeit moderate in size ( r = .27)—predictor of academic dishonesty according to a recent meta-analysis of 89 effects and 50 studies [ 22 ]. In the present study, we wanted to further examine the relationship between academic dishonesty and psychopathy by using the triarchic model of psychopathy distinguishing its three phenotypic facets: boldness, meanness, and disinhibition [ 23 ] which may reveal added nuance to how this personality trait relates to academic dishonesty.

Within the triarchic conceptualization of psychopathy, boldness represents self-assurance, fearlessness, and a high tolerance for stress and unfamiliarity; meanness captures interpersonal deficits such as lack of empathy, callousness and exploitativeness; and disinhibition represents the tendency towards impulsivity, poor self-regulation and focus on immediate gratification. Because of the different neurobiological mechanisms leading to the shaping of those aspects [ 24 ], it seems likely that the tendency towards academic dishonesty may have a different etiology depending on their levels. For students with high disinhibition, cheating may result from low self-control; for those with high meanness from rebelliousness with propensity to use others; and for bold ones from emotional resiliency and sensation-seeking [ 25 – 27 ]. However, because boldness constitutes fearlessness without failed socialization [ 28 ], breaking academic rules might not be the preferred way to look for excitement among bold students. Thus, our first goal was to examine the predictive power of boldness, meanness, and disinhibition in academic dishonesty.

Furthermore, we were interested if the relationships between the psychopathy facets and academic dishonesty would be mediated by individual differences in motivations for mastery and performance. Mastery motivation is fostered by the need for achievement and associated with learning to acquire knowledge, whereas performance motivation is geared towards reducing anxiety and related to learning to prove oneself to others [ 29 ]. We expect mediation for several reasons. First, undertaking actions motivated by achievement goals is predicted by the level of positive and negative emotionality and also by activity of the behavioral activation and inhibition system [ 30 ], which also correlate with the dimensions of the triarchic model of psychopathy [ 31 ]. Second, unrestrained achievement motivation partially mediates the relationship between psychopathy and academic dishonesty, suggesting a role of achievement in understanding the relationship between psychopathy and individual differences in the propensity to cheat [ 32 ]. Third, meanness and disinhibition are negatively and boldness positively correlated with conscientiousness and its facets [ 33 , 34 ]. This fact may play an important role in students’ willingness to exert and control themselves to achieve academic goals and the particular way to do it [ 35 ]. Moreover, research on mastery-goal orientation suggests it is correlated negatively with academic dishonesty and views of the acceptability of academic dishonesty [ 36 – 38 ] and that the change from mastery to performance-based learning environment lead to increased levels of dishonesty [ 39 ].

Therefore, we hypothesized that students with a high level of disinhibition may have difficulties studying because of their need for immediate gratification and lack of impulse control, and in turn, cheat to pass classes. Bold students could want to acquire vast knowledge and high competences because of their high self-assurance, social dominance, and a high tolerance for stress without resorting to fraud. Lastly, students with a high level of meanness may be less prone towards mastery through hard work and learning because of their susceptibility to boredom, tendency to break the rules, and to exploit others to their advantage, perhaps by copying or using other students’ work. Because performance-goal orientation can be driven by the fear of performing worse than others, no specific hypothesis was generated regarding its relation to psychopathy (characterized by a lack of fear).

Besides behavioral tendencies based on personality traits and specific motives to learn, another closely related predictor of academic dishonesty is general self-efficacy. People with high levels of general self-efficacy exercise control over challenging demands and their behavior [ 40 ] and perform better in academic context because of their heightened ability to solve problems and process information [ 41 ]. On the other hand, low levels of general self-efficacy in the academic context can lead to reduced effort and attention focused on the task, which may result in a higher probability of frauds to achieve or maintain a certain level of academic performance [ 42 , 43 ]. Because competence expectancies are important antecedents of holding an achievement goal orientation [ 44 , 45 ] it seems possible that general self-efficacy might moderate the relation between psychopathy facets and academic dishonesty mediated by achievement goals. Thus, we hypothesize that high general self-efficacy will reduce the indirect effects for disinhibition and meanness (i.e., negative moderation effect) and amplify it for boldness (i.e., positive moderation effect).

In sum, we examine the relationships between three facets of psychopathy and academic dishonesty, the possible role of achievement goals as a mediators for those relations, and lastly the possible role of general self-efficacy as a moderator of those mediation models. By analyzing the facets of psychopathy independently, we can determine their unique relationship with the tendency to cheat and thus more accurately predict the risk of dishonest behavior for students with a high level of each of the facet. In addition, investigating indirect effects and interactions between personality and motivation may describe the psychological processes that may lead to cheating and can potentially be used in planning preventive actions.

Materials and methods

Participants and procedure.

The participants were 390 Polish university students and residents (100% White, 74% female) with an average age of 23 ( SD = 3.39, Range = 19–56) years. Participants self-identified as students in social sciences (17%), humanities (12%), science and technology (24%), law and administration (22%), and medical sciences (23%); 7 failed to respond (2%). In addition, participants were first-year (19%), second-year (16%), third-year (31%), fourth-year (13%), fifth-year (13%), and doctoral students (2%); 23 failed to respond (6%).

We established the required sample size as 290 participants, following Tabachnick and Fidell [ 46 ] guidelines and gave ourselves three months to collect it to avoid concerns with power and p- hacking, respectively. The study was approved by Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Pedagogy and Psychology (University of Silesia in Katowice) and was conducted online through the Webankieta platform to maximize the anonymity and security of the participants. An invitation to participate in the project was sent to 28 largest Polish universities by enrollment, with a request to publish it on the universities' websites. The link to the survey directed the participants to a detailed description of the research and the rules of participation. After consenting to participate, students completed online questionnaires and, at the end, they were asked if they wanted to receive a summary of the general results and take part in a prize drawing (after the end of the study, five randomly chosen participants received vouchers for online personal development courses). The present study was part of a larger investigation that aimed to examine psychological determinants and predictors of academic dishonesty.

Psychopathy was measured with the TriPM-41 [ 34 ], the shortened Polish adaptation of the Triarchic Psychopathy Measure [ 47 ]. Participants rated statements on a 4-point scale (0 = completely false ; 1 = somewhat false ; 2 = somewhat true ; 3 = completely true ). Items were summed to create indexes for three subscales: disinhibition (16 items, e.g., “I jump into things without thinking”; Cronbach’s α = .83), meanness (10 items, e.g., “I don't have much sympathy for people”; α = .92), and boldness (15 items, e.g., “I'm a born leader”; α = .88).

Achievement goals were measured with the Polish translation of the Achievement Goals Questionnaire-Revised [ 29 ]. Participants reported their agreement (1 = strongly disagree ; 5 = strongly agree ) with statements such as “My aim is to completely master the material presented in this class” (i.e., mastery-goal orientation, 6 items) or “My aim is to perform well relative to other students” (i.e., performance-goal orientation, 6 items). Items were summed to calculate mastery (α = .80) and performance (α = .87) goal orientation indexes.

The Polish translation of the New General Self-Efficacy Scale [ 48 ] was used to measure general self-efficacy (e.g., “Even when things are tough, I can perform quite well”). Participants were asked how much they agreed (1 = strongly disagree ; 5 = strongly agree ) with eight items, which were summed to create the general self-efficacy index (α = .89).

Academic dishonesty was estimated with the Academic Dishonesty Scale [ 49 ], which is a list of 16 academically dishonest behaviors (e.g., “Using crib notes during test or exam” or “Falsifying bibliography”). Participants rate the frequency (0 = never ; 4 = many times ) of committing each behavior during their years of studies. Items were summed to create the academic dishonesty index (α = .83).

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated with JASP (v0.9.0.0), correlations with STATISTICA (v13.1), and regression, mediation, and moderated mediation with SPSS (v25). In the mediation analysis we used model 4 in macro PROCESS 2.16.3 (10,000 bootstrapped samples) and for the moderated mediations model 7 in macro PROCESS 2.16.3 (10,000 bootstrapped samples). Analyzes were carried out on the responses from 390 fully completed surveys. Because of mixed results in previous studies concerning psychopathy and academic dishonesty levels in men and women (see [ 50 , 51 ]) we conducted analyses on the overall results and also separately in each sex. The database was uploaded to Open Science Framework and is available under the following address: https://osf.io/frq9v/

Descriptive statistics, sex differences tests (see Bottom Panel), and correlations (see Top Panel) for all measured variables are presented in Table 1 . Academic dishonesty was positively correlated with meanness and disinhibition, and negatively correlated with mastery-goal orientation and general self-efficacy. Mastery-goal orientation was positively correlated with boldness and general self-efficacy, and negatively correlated with meanness and disinhibition. Performance-goal orientation was positively correlated with meanness. General self-efficacy was positively correlated with boldness and negatively correlated with meanness and disinhibition. We found only three cases where these correlations were moderated by participant’s sex. The correlation between performance and mastery-goal orientation was stronger ( z = -1.85, p = .03) in men ( r = .51, p < .01) than in women ( r = .34, p < .01). The correlation between mastery-goal orientation and meanness was stronger ( z = 2.00, p = .02) in men ( r = -.28, p < .01) than in women ( r = -.05, ns ). And the correlation between disinhibition and academic dishonesty was stronger ( z = 1.72, p = .04) in women ( r = .39, p < .01) than in men ( r = .20, p < .01). If we adjust for error inflation for multiple comparisons ( p < .007) for these moderation tests, none of the Fisher’s z tests were significant. Therefore, we conclude the correlations were generally similar in the sexes. Men scored higher than women on meanness and disinhibition.

- PPT PowerPoint slide

- PNG larger image

- TIFF original image

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0238141.t001

To test the contribution of personality and motivation variables in predicting academic dishonesty, we conducted a standard multiple regression where the model explained 23% of the variance in academic dishonesty [ F (6, 383) = 18.60, p < .001]. The residuals for boldness ( β = .12, p = .04), disinhibition ( β = .27, p < .01), and a mastery-goal orientation ( β = -.39, p < .01) were correlated with academic dishonesty. Additional regression analysis revealed that both mastery-goal orientation and disinhibition strengthened the association between boldness and academic dishonesty, which on its own was not a predictor of the frequency of cheating–suppressor effect (results of hierarchical regression showed that after adding boldness to the model explained variance increased by 1% [Δ F (1, 383) = 4.40, p = .04]).

To examine whether achievement goals mediated the associations between psychopathy and academic dishonesty we conducted a series of mediation analyses.

As shown in Table 2 (see Left Panel), mastery-goal orientation mediated the relation between facets of psychopathy and academic dishonesty (i.e., none of the indirect effects CIs contained zero), and performance-goal orientation was not a mediator of those relations (see Right Panel; all of the indirect effects CIs contained zero). Mastery-goal orientation mediated relation between disinhibition and academic dishonesty (i.e., initial 𝛽 Step 1 = .32, p < .001; 𝛽 Step 2 = .24, p < .001), and the relationship between meanness and academic dishonesty (i.e., 𝛽 Step 1 = .10, p < .05; 𝛽 Step 2 = .05, p = .29). Initial non-significant negative relation between boldness and academic dishonesty (𝛽 = -.0001, p = .99) stayed unrelated after adding mastery-goal orientation to the model, but the value for the relation coefficient was higher and positive (𝛽 = .07, p = .12) suggesting a nonsignificant suppression effect.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0238141.t002

To test if the level of general self-efficacy moderated the aforementioned relationships between psychopathy, achievement goals, and academic dishonesty we ran a series of moderated mediations. Index for moderated mediation was significant only for the model with disinhibition and mastery-goal orientation ( - 0.03; 95% CI: -0.70, -0.003), however, the same analyses ran separately for men ( - 0.03; 95% CI: -0.13, 0.05) and women ( - 0.04; 95% CI: -0.08, -0.01) revealed moderated mediation only in women (therefore, we do not report these analyses in men; they can be obtained from the first author). Estimates for that model are presented in Table 3 .

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0238141.t003

Women with high levels of disinhibition manifesting low level of mastery-goal orientation (see Left Panel, line A1) declared higher levels of academic dishonesty (see Right Panel, line B). An interaction between disinhibition and general self-efficacy (see Left Panel, line A3) with the significant, negative index for moderated mediation means that the indirect effect of disinhibition on academic dishonesty through mastery-goal orientation is negatively moderated by general self-efficacy. The higher the level of the moderator, the weaker the effect of mediation, and for moderator values above one standard deviation from mean mediation become non-significant (95% CI: -0.01, 0.09). In sum, the mastery-goal orientation partially mediated the associations that disinhibition had with academic dishonesty, however, this effect was absent for people with high levels of general self-efficacy.

Discussion and limitations

Psychopathy is an important predictor of engaging in unethical behaviors [ 52 ], including in an academic context [ 53 ]. In the present study, we examined the relationships between facets of psychopathy, as described in the triarchic model of psychopathy (i.e. disinhibition, meanness, and boldness), and the frequency of academic dishonesty among students. We revealed that students with higher levels of meanness and disinhibition, but not boldness, reported more frequent academic dishonesty during their tertiary study.

In the case of meanness, this relationship may indicate a tendency for dishonesty resulting from a lack of fear and, consequently, a diminished impact of the perceived risk of being caught cheating, sensation-seeking that involves engaging in destructive behavior regardless of possible negative consequences of such actions, and a propensity to exploit other student’s work or knowledge to pass classes [ 23 , 54 ]. The association between disinhibition and academic dishonesty may indicate impulsive cheating resulting from self-control problems (see [ 55 ]), and an inability to predict possible negative consequences of cheating [ 26 ]. The fact that academic dishonesty and boldness were uncorrelated may indicate that even though bold students can perform successfully in stressful situations and have high levels of sensation-seeking, those features are unrelated to the tendency to cheat in the academic context. It confirms that the “successful psychopath” [ 56 ] may be characterized by boldness but not antisocial behavior. Of all the facets of psychopathy, disinhibition was the strongest predictor of academic dishonesty, which confirms the role of impulsivity in predicting risky behavior [ 57 , 58 ], and the role of delaying gratification in refraining from academic transgressions [ 59 ].

Beyond these basic associations, we also examined the role of achievement goals as mediators for the relationships between psychopathy facets and academic dishonesty. Mastery-goal orientation mediated the relationships between two psychopathy facets and academic dishonesty. Both meanness and disinhibition led to low levels of students’ mastery-goal orientation which, in turn, contributed to cheating in the academic context. Low mastery-goal orientation might result from the fact that those who are characterized by meanness may have a propensity to be rebellious (e.g., disregard for formal responsibilities, low diligence, and sensitivity to rewards) and those who are characterized by disinhibition may have a propensity for impulsivity (e.g., inability to postpone gratification or control impulses, high behavioral activation system). Without motivation to acquire knowledge, students may cheat to achieve academic goals with no regard to the fairness (i.e., high meanness) or the consequences (i.e., high disinhibition) of their actions [ 31 – 33 ]. In the case of boldness, the result of the mediation analysis might indicate a cooperative or reciprocal suppression effect, however, it should not be trusted because the main effect path did not pass the null hypothesis threshold when the potential suppressor was included in the model. Nonetheless, it seems possible that a particular configuration of boldness and disinhibition could lead to the interactive effect of those facets on the other variables [ 26 ]. Performance-goal orientation did not mediate the relationships between psychopathy facets and academic dishonesty, probably because bold, mean, and disinhibited students are not motivated by the fear to perform worse than others [ 60 ].

Lastly, we tested if general self-efficacy acts as a moderator of these mediation models and found evidence that it moderated the indirect effect of disinhibition on academic dishonesty through mastery-goal orientation. This means that disinhibited students who have a high sense of perceived ability to control their chances for success or failure, might be able to overcome the tendency to cheat resulting from their personality (i.e., high impulsiveness), and motivational (i.e., low motivation to learn) predispositions. However, that effect was found only for women, limiting any insights that can be drawn about men. Previous research showed that an increase in general self-efficacy reduced the risk of suicide among women [ 61 ]. Moreover, Portnoy, Legee, Raine, Choy, and Rudo-Hutt [ 62 ] found that low resting heart rate was associated with more frequent academic dishonesty in female students, and that self-control and sensation-seeking mediated this relationship. Thus, along with the observed lower level of disinhibition for female students, it appears that self-regulation abilities may play a different role for men and women’s performance, and also that deficits in self-control might not lead to the same behavioral tendencies in the sexes (see [ 63 ]). However, because of the cross-sectional nature of our study and an uneven number of men and women in the sample, this needs to be investigated further.

In the present study, we aimed to combine personality and motivation variables to describe the possible process leading to academic dishonesty assessed with a behavioral measure. Because Polish students do not constitute a typical W.E.I.R.D. sample (i.e., Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic), presented results can be used to generalize conclusions from research on academic dishonesty beyond typical W.E.I.R.D cultures. However, our study is not without limitations. First, the measurement of academic dishonesty was based on self-report, which, even after maximizing anonymity of the measurement, might have attenuated our results concerning the frequency of cheating. Thus, future studies should focus on measuring actual dishonest academic behavior. Second, we examined academic dishonesty as an overall frequency of committing different acts of cheating, which reflects the general propensity to cheat. It could be useful to further investigate the predictive power of described models in experiments, focused on the specific type of dishonest behavior. Third, the obtained range of academic dishonesty scores might result from sampling bias, which would require using different sampling procedure in future studies, or from non-normal distribution of academic dishonesty, which would be consistent with the results of the previous studies [ 2 – 4 ]. Fourth, we tested mediation models in a cross-sectional study with a one-time point measurement, which require cautious interpretation. Future studies could use longitudinal methods; starting at the beginning of the first year and continuing over the course of their studies to capture the influence of personality, achievement goals, and general self-efficacy on the academic dishonesty of students in a more robust manner. Despite these shortcomings, our study is the first attempt (we know of) to integrate the triarchic model of psychopathy, general self-efficacy, and achievement goals to predict academic dishonesty, showing potential for further investigation in this area.

Implications and conclusions

Preventing academic dishonesty is often made difficult by the lack of centralized and formalized university policies concerning cheating, faculty reluctance to take formal action against dishonest students, and limited attention paid to students’ personal characteristics associated with a tendency to cheat [ 64 ]. Based on the results of our study, lecturers might overcome those difficulties by: maximizing the amount of oral examinations to deal with the risk of cheating by disinhibited and mean students; enhancing students’ mastery-goal orientation, for example, by increasing use of competency-based assessment; enhancing students’ self-efficacy in academic context, for example, by providing spaced assessed tasks, and the opportunity to practice skills needed for their fulfillment. In the case of dealing with actual dishonest behavior, the fact that teachers prefer to warn students rather than fail them [ 19 ] might suggest indifference to academic integrity rules, reluctance to initiate time-consuming formal procedures against cheating, or teachers’ preference toward autonomy to deal with dishonesty. Therefore, a useful solution could be to assess which areas need to be improved for a particular student (e.g., knowledge about plagiarism, ability to delay gratification, or treating acquisition of knowledge as a value) and to allow the teacher to choose an effective way to remedy them.

In sum, we presented evidence that disinhibition and meanness are associated with the frequency of committing academic dishonesty. We described the possible underlying mechanism of those relations involving mediation effects of the mastery-goal orientation and, in the case of disinhibition, also a moderation effect of the general self-efficacy. Our research can be used by teachers to better identify factors conducive to dishonesty and to modulate their responses to fraud based on the personality and motivational predispositions of students.

Supporting information

S1 table. descriptive statistics and correlations for academically dishonest behaviors..

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0238141.s001

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr Guy Curtis for his comments and suggestions on the article.

- View Article

- Google Scholar

- PubMed/NCBI

- 28. Hall JR. Interview assessment of boldness: Construct validity and empirical links to psychopathy and fearlessness (Doctoral dissertation). University of Minnesota, Minneapolis. 2009. Available from: https://conservancy.umn.edu/handle/11299/54181

- 45. Schunk DH, Pajares F. Competence perceptions and academic functioning. In: Elliot AJ, Dweck CS, editors. Handbook of Competence and Motivation. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2005. pp. 85–104.

- 46. Tabachnick BG, Fidell LS. Using multivariate statistics (Vol. 5). Boston, MA: Pearson; 2007.

- 47. Patrick CJ. Operationalizing the triarchic conceptualization of psychopathy: Preliminary description of brief scales for assessment of boldness, meanness, and disinhibition. Unpublished test manual. Tallahassee, FL: Florida State University; 2010. Available form: https://patrickcnslab.psy.fsu.edu

- 56. Hall JR, Benning SD. The “successful” psychopath. In: Patrick CJ, editor. Handbook of Psychopathy. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2006. pp. 459–478.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 19 August 2022

The effects of personality traits and attitudes towards the rule on academic dishonesty among university students

- Hongyu Wang 1 &

- Yanyan Zhang 1

Scientific Reports volume 12 , Article number: 14181 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

4692 Accesses

5 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Human behaviour

Academic dishonesty is becoming a big concern for the education systems worldwide. Despite much research on the factors associated with academic dishonesty and the methods to alleviate it, it remains a common problem at the university level. In the current study, we conducted a survey to link personality traits (using the HEXACO model) and people’s general attitudes towards the rule (i.e., “rule conditionality” and “perceived obligation to obey the law/rule”) to academic dishonesty among 370 university students. Using correlational analysis and structural equation modeling, the results indicated that both personality traits and attitudes towards the rule significantly predicted academic misconduct. The findings have important implications for researchers and university educators in dealing with academic misconduct.

Similar content being viewed by others

Sordid genealogies: a conjectural history of Cambridge Analytica’s eugenic roots

Personality and socio-demographic variables in teacher burnout during the COVID-19 pandemic: a latent profile analysis

Predictors and consequences of intellectual humility

Introduction.

Academic dishonesty is a global issue that attracts much attention from educators worldwide, and relevant research could date back to the last century 1 . It is considered immoral and inappropriate because the behavior has an unfair advantage over other students and impedes individuals’ capacity to study 2 , 3 . Dishonesty behavior often starts early in school, such as copying others’ work, and has been a consistent and paramount problem throughout all education levels 4 . It is an educational and academic issue with severe consequences 5 . Engagement in academic dishonesty predicts increased acceptance of immoral workplace behavior, indicating its continuous influence post-graduation 6 , 7 . At the university level, such misconduct behavior has clear potential to diminish the reputation and integrity of universities. It hinders universities’ ability to ensure that students who achieve degrees have the knowledge and skills they require for employment or further study 8 .

Much literature on the individual predictors of academic cheating has mostly focused on the influences of personality traits, academic attitudes & values, and some demographic variables 9 . Several personality traits were found to be significantly predictive, such as impulsivity 10 , psychopathy 11 , Machiavellianism and narcissism 12 . Self-control may explain why people do, or do not, engage in plagiarism when the opportunity is available 13 . Curtis et al. 14 found that self-control and academic misconduct were negatively correlated. Although individuals’ self-control can vary depending on situational factors such as mood, fatigue, and hunger, it is more like stable personality-like differences 15 .

Research on the demographic variables found that age and gender are critical factors predicting academic misconduct. For instance, as they age, female college students are less likely to engage in academic dishonesty due to fewer comparisons between one’s own behaviors and peer behaviors 16 . However, age and gender are not consistently found to be significant factors in most research on academic misconduct 9 , 17 .

In the current study, we still focused on these individual factors with attempts to 1) assess a recent model of personality (i.e., HEXACO) and its predictive power of academic dishonesty; and 2) to link people’s general attitude towards the rule/law to academic dishonesty, considering that it is essentially a violation of the rules in academia. Age and gender effects are examined along with the above goals.

Academic dishonesty

Academic dishonesty, academic misconduct, academic cheating, and academic integrity are concepts often used interchangeably in previous literature. The concept is usually defined through behavioral classifications. Pavela 18 considered academic dishonesty to contain four main types of misconduct that deliberately violate school regulations: cheating, fabrication, facilitation, and plagiarism. McCabe and Trevino 19 further expanded the scope of this concept into 12 types of violating behaviors in school, including sneaking at notes in the exam, copying others’ answers in the exam, copying others’ answers without their permission in the exam, etc. These researchers developed a 12-item scale to measure academic dishonesty, which is widely used 19 , 20 . However, Adesile and Nordin 21 criticized that the psychometric properties have not been critically investigated despite their broader literature application. To validate the psychometric properties of the instrument and determine the dimensionality of academic dishonesty, Adesile 21 adapted the original scale, divided academic dishonesty into three dimensions (“cheating,” “plagiarism,” and “research misconduct”), and named it “the academic integrity survey.”

Academic dishonesty is found to be largely explained by individual factors 22 . Motivation is one of the major individual factors relating to academic dishonesty. Through a meta-analytic investigation, Krou and colleagues 23 reviewed 79 studies and reported that academic dishonesty was negatively associated with intrinsic motivation, self-efficacy, utility value, and internal locus of control, and was positively associated with amotivation and extrinsic goal orientation. Motivation, however, may vary across different cultural backgrounds. A recent study of Chinese university students found that their unethical academic behaviors are associated with their unique motivation to meet parents’ expectations 24 .

Morality is another crucial predictor of academic cheating and plagiarism. Individuals with a high level of morality, emphasis on fairness, and value of social rules have stringent attitudes towards plagiarism 25 , 26 , 27 . Meanwhile, moral disengagement is positively associated with cheating 28 . The predicting effect of morality may also be inconsistent across cultures. Ampuni et al. 29 studied the relationship between academic dishonesty and the five moral foundations in Indonesia, and found only a weak predictive power of the “authority” foundation on academic dishonesty.

Since the COVID-19 epidemic outbreak, courses and examinations have been conducted online, and researchers are concerned that academic misconduct in online learning environments has become more serious 30 . Studies, however, provided little and even opposite evidence regarding the actual behavioral differences in academic misconduct between traditional and online settings. Peled et al. 31 found that students tend to engage less in academic dishonesty behaviors online than in face-to-face courses. In addition, cheating intentions among students in traditional and online education settings are very little 32 . To reconcile the inconsistent findings, researchers started considering potential moderating and mediating factors such as the types of academic dishonesty, the level of technology complexity, and statistics anxiety 33 , 34 , 35 .

Personality traits and academic dishonesty

Personality reflects a person’s consistent patterns of thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. It has a large effect on individuals’ academic behaviors. The Big Five personality model is the most widely used predictor of academic dishonesty. For instance, Giluk and Postlethwaite 36 reviewed studies of both high school and university students, and concluded that conscientiousness and agreeableness (of the Big Five) are the strongest predictors of academic dishonesty. Graziano and Eisenberg 37 found agreeable people more trusting and less cynical. As a result, they were less likely to justify cheating and see it as a necessity to compete with others. Lee et al. 9 conducted a meta-analysis on predictors of academic dishonesty and confirmed the strong relationship between agreeableness and academic dishonesty. They also found openness to be associated with self-efficacy/personal ability, and in turn, was negatively related to academic dishonesty. Finally, a positive association between neuroticism and academic procrastination increased cheating behaviors at school 38 .

Empirical evidence on the relationship between extraversion and academic dishonesty, however, is not consistent. For example, some research found a small positive association between extraversion and scholastic dishonesty 11 , while others indicated a moderate negative association 39 , and nonsignificant findings 36 .

Ashton and Lee 40 extended the Big Five personality model with a set of lexical studies, and developed a six-dimension model, referred to as the HEXACO model of personality structure. The name of this model reflects both the number of factors (i.e., the Greek hexa , six) and their names: Honesty-Humility (H), Emotionality (E), extraversion (X), Agreeableness (A), Conscientiousness (C), and Openness to Experience (O). It is essential the Big Five personality plus an additional Honesty-Humility dimension. The six-dimensional structure was more replicable across cultures than the Big Five model, as the Big Five structure has failed to present in four languages that recovered the HEXACO dimensions 41 . It has become a major tool in measuring personality traits in the early 21st century.

The HEXACO model, particularly the Honesty-Humility (H) dimension, is proven to be very useful in predicting many unethical behaviors. Kleinlogel et al. 42 investigated the relationship between Honesty-Humility and cheating behavior. Results showed that individuals high in Honesty-Humility were less likely to cheat than those low on this trait. Honesty-Humility was negatively associated with adolescents’ unethical behavior, and moral disengagement partially mediated this negative association 43 . Hilbig and Zettler 44 found that German adults who were low in Honesty-Humility were more likely to behave dishonestly across various experimental situations (e.g., coin-toss task and dice-task). Honesty-Humility was negatively associated with unethical business decisions among people from Fiji and the Marshall Islands 45 . Honesty-Humility was proved to be the strongest predictor of cheating, dishonesty, counterproductive behavior, and antisocial behavior, according to a meta-analysis 41 . Accordingly, the current study posits that,

Hypothesis 1

All six dimensions of the HEXACO model will predict academic dishonesty. Specifically, Honesty-Humility (H), Agreeableness (A), Conscientiousness (C), Openness to Experience (O), and Emotion Stability (E) are all expected to predict academic dishonesty negatively.

Attitudes towards the rule: perceived obligation of rule/law and rule conditionality

The concept of the perceived obligation of law/rule proposed (short for POOL) by Tyler 46 refers to individuals’ variability in perceptions of obeying general laws. The higher the endorsement, the more likely they are to comply with laws and rules. If one’s POOL level is high, it has nothing to do with the fear of violating and thus being punished by the laws, and it is also not because someone sees other people’s compliance behaviors and tries to conform and comply. POOL exists at the personal level, which arises from people’s knowledge and conscience to stand up for the laws and rules.

Tyler’s research has shown a negative link between POOL and general criminal behavior. The more one perceives an obligation to obey the law, the less likely one will violate the law 47 . In other words, if one’s POOL is higher, one is not expected to perform academic misconduct, as the person would like to obey the rule or law, and volunteer to restrain one’s behavior. POOL is also found to be a key element in predicting compliance behavior to slow the spread of the virus during the COVID-19 pandemic 48 .

Rule conditionality (RC), also called rule orientation, assess the extent to which an individual perceives it is acceptable to violate the legal rules under certain conditions 49 . In other words, less rule-oriented people accept more reasonable circumstances to break the rules, and those who are more rule-oriented acknowledge fewer acceptable circumstances to violate the regulations.

RC derives from POOL and negatively relates to POOL, but they are very different. RC presents the level of flexibility when people evaluate different circumstances to break the law or rules. POOL is a sense of one’s obligation and duty to obey the laws and regulations. RC played a crucial role in predicting compliance behaviors and law violations. When laws go against personal morals, people will weigh the advantages, and disadvantages of immoral behavior, combined with moral belief, the lack of knowledge of the law, cost-benefit analysis, social norms, and lack of procedural justice are all critical roles in influencing the possibility of violating the law 49 .

In general, since both POOL and RC are stable personality-like variables that do not vary across mood and situations, and because misconducts in academia are rule violations by their nature (although the consequences are not similarly severe as law violations), we expect that students’ perception of the duty to obey the law/rule and their sense of rule conditionality would both be significant predictors of academic dishonesty. Accordingly, the current study expects that ,

Hypothesis 2

RC positively predicted academic dishonesty, and POOL negatively predicted academic dishonesty. That is, participants who are more likely to consider rules as conditional, will report more cheating behaviors. In contrast, participants who perceive more obligation to obey the law, will report fewer cheating behaviors.

The current study has been approved by the IRB of School of Philosophy and Sociology of Jilin University. Informed consent has been obtained from all participants of the present study. All methods were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations.

The sample consists of 370 students coming from a Northern Chinese University. The mean age of the participants was 19.77 years old (SD = 3.63). 224 (60.54%) participants majored in sciences and 146 (39.46%) participants majored in humanities and social sciences. 211 (57.03%) were male students, and 159 (42.97%) were female students.

Instruments

All research instruments were originally in English, translated into Chinese by a psychology graduate student, and back-translated by a bilingual psychology researcher.

Academic dishonesty (AD)

The Academic Integrity Survey (AIS) 50 was used to measure academic dishonesty (α = 0.916). It contains 15 items assessing the “Cheating,” “Research Misconduct,” and “Plagiarism” of academic misconduct. The survey comprised an 8-point Likert scale (1 = ‘very strongly disagree’; 8 = ‘very strongly agree’). A higher score on the scale indicated a higher level of academic dishonesty. The internal consistency for the whole scale in current study was 0.955, with Cronbach’s alpha being 0.919, 0.812, and 0.817 for “Cheating,” “Research Misconduct,” and “Plagiarism,” respectively.

Personality

The HEXACO model 40 , a six-dimension structure containing the factors Honesty-Humility (H), Emotionality (E), Extraversion (X), Agreeableness (A), Conscientiousness (C), and Openness to Experience (O), was used as a measure of personality, with 60 items in total. The internal consistency reliabilities ranged from 0.77 to 0.80 in the college sample and from 0.73 to 0.80 in the community sample 51 . The HEXACO-60 comprised a 5-point Likert scale (1 = ‘strongly disagree’; 5 = ‘strongly agree’). Cronbach’s alpha was 0.795(α HH = 0.701, α EX = 0.748, α EM = 0.642, α AG = 0.649, α CO = 0.609, α OP = 0.668) in the current study.

Rule conditionality (RC)

Rule Conditionality Scale 49 was utilized to indicate the extent to which individuals perceive acceptable conditions for breaking the law in general (α = 0.928). The 7-point Likert scale (1 = ‘strongly disagree’; 7 = ‘strongly agree’) contains 12 items, which is calculated as a mean score ( M = 3.49 , SD = 1.08), with higher scores indicating more rule conditionality (i.e., the individual accepts fewer justifications for violating laws). Cronbach’s alpha was 0.868 in the current study.

Perceived obligation to obey the law (POOL)

Perceived Obligation to Obey the Law 47 includes six items on a 4-point Likert scale (1 = ‘strongly disagree’; 4 = ‘strongly agree’, α = 0.64). The POOL was calculated as a mean score of all items (M = 2.78, SD = 0.61), with a higher score indicating a higher perceived obligation to obey the law. Cronbach’s alpha was 0.671 in the current study.

Participants were offered course credits to take part in an online study. Wenjuanxin was used as the data collection platform, providing functions equivalent to Amazon Mechanical Turk. The participants were asked to answer the AIS, HEXACO, RC, and POOL questionnaires and then reported demographic information (gender and age). Data were excluded from the analysis if the participants failed to choose the correct answer of the “filter” items (e.g. “Please choose #1 on this question”). A total of 397 questionnaires were collected and 370 were valid (rejection rate = 6.80%).

Data analysis

SPSS and Amos 26.0 were used for data analysis. Pearson correlation analysis and structural equation model were conducted to test the hypotheses.

Results of the correlation analysis

Pearson correlation was used to examine the correlations among the variables. Regarding the effects of demographic variables on academic dishonesty, age was positively correlated with academic dishonesty (r = 0.208, p < 0.01). As age increased, people were more likely to conduct various academic misconducts.

Regarding the effects of personality traits on academic dishonesty, as expected and in line with a prior study 9 , we found strong negative correlations between personality and academic dishonesty on all six dimensions. Specifically, academic dishonesty was negatively predicted by honesty-humility (r = − 0.362, p < 0.01), emotion stability (r = − 0.119, p < 0.05), agreeableness (r = − 0.246, p < 0.01), conscientiousness (t = − 0.231, p < 0.01), openness to experience (r = − 0.190, p < 0.01), and extraversion (r = − 0.185, p < 0.01).

Finally, regarding the effect of attitudes towards the rule on academic dishonesty, rule conditionality was positively correlated with academic dishonesty (r = 0.231, p < 0.01). It showed that academic misconduct was more acceptable as students scored higher on rule conditionality, consistent with the hypothesis. Contrary to the hypothesis, however, perceived obligation to obey the law/rule was not correlated with academic dishonesty (r = − 0.009, p = 0.864). In addition, POOL was also not associated with five of six personality dimensions nor rule conditionality (r HH = − 0.001, p = 0.984; r EM = 0.043, p = 0.413; r EX = 0.009, p = 0.861; r AG = 0.012, p = 0.816; r CO = 0.007, p = 0.897; r RC = − 0.016, p = 0.761) (see Table 1 ).

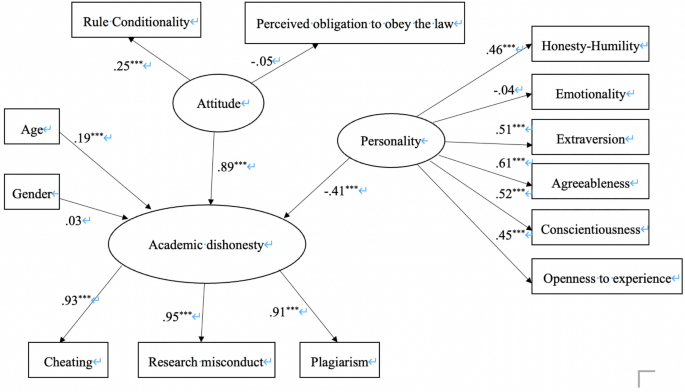

Results of the structural equation modeling

The structural equation models linking the demographic variables (age and gender), the personality variables (HEXACO), and the attitude variables (RC and POOL) were tested. The findings were presented in Fig. 1 . The model was examined for the goodness of fit using indices including Chi-square, comparative fit index, and root mean square error of approximation. The results indicated an overall good model fix (χ2 = 180.714, χ2 /df = 2.82, p < 0.001; CFI = 0.922; RMSEA = 0.070) 52 .

Structural model for determinants of academic dishonesty.

In general, students’ tendency to engage in academic dishonesty was accounted for by the demographic variables, the personality variables, and the attitude variables. Specifically, consisting to the results of correlation analysis, age but not gender positively predicted academic dishonesty. The HEXACO model negatively predicted academic dishonesty, with five out of the six dimensions being significant except for the emotionality dimension. It indicated that people who scored higher on honesty-humility, agreeableness, conscientiousness, openness to experience, and extraversion were less likely to engage in academic misconduct. In addition, rule conditionality positively predicted academic dishonesty, indicating that individuals who believed in the conditionality of rules were more likely to misbehave at school. These results partially aligned with the hypotheses.

The purpose of this study is to explore the influence of individual factors (personality and people’s general attitudes toward the rules) on academic dishonesty. A survey among university students was conducted, and the results provided evidence that both personality traits and people’s rule orientation had significant effects on their various academic misconducts. The HEXACO model is a relatively recent personality model to expand and replace the Big Five personality model, and its cross-cultural applicability has been verified in many research settings 41 . The current study applied the HEXACO model in predicting academic dishonesty for the first time, and our findings justified its application.

Attitudes towards the rule are manifested in two aspects. Rule conditionality assessed whether individuals would violate relevant regulations and commit deviant behaviors under certain circumstances. Perception of the obligation to obey the law and rules (POOL) assessed individuals’ sense of duty to avoid behaviors that violate regulations, such as academic misconduct. Results of the current study demonstrated that rule conditionality positively predicted academic misconduct; that is, individuals who believed that rules are conditional and could be broken under certain conditions are more likely to engage in various academic transgressions. POOL, however, was not found to be related to academic dishonesty. Previous results showed that Chinese students scored lower on the POOL than American students 53 . POOL is likely an inadequate measure of Chinese students’ sense of obligation and duty to obey the laws and rules. Future research could use a different sample to test the predicting effect of POOL on academic dishonesty, and should also consider revising and refining the POOL measure for cultural research.

Regarding the predictive effect of demographic variables on academic misconduct, only age was found to have a significant positive correlation with academic misconduct. Gender had no effect which is consistent with the previous literature 9 , 17 .

Conclusion and implication for future research

The current study examined the HEXACO model and peoples’ attitudes toward the rule to better understand the academic misconduct behaviors among university students. Our findings have important implications for researchers and institutional educators. We demonstrated that in addition to the tractional big five personality factors, honesty-humility is a unique contributor to decreasing academic dishonesty. Recent studies have suggested focusing on integrity as the broadest defense against dishonesty in all spheres of academia 54 . Our research findings encourage university educators and institutional policymakers to pay much attention to this dispositional protector.

Our study also linked law-abiding attitudes with academic behaviors. Legal laws and academic rules share features in regulating people’s behaviors by imposing sanctions. They are quite different from social norms, which is a rather indirect way of behavior regulation. The current study confirmed that rule conditionality plays an important role in predicting academic misconduct of university students. Thus law-abiding education and behavior modification interventions might also be effective in preventing academic dishonesty.

Our results have contributed to the academic dishonesty field, but it is not free from limitations. First, it was a correlational study, meaning it is only possible to speak about relationships but not causal links. Experiments are necessary for future research. In addition, we did not control the participant’s prior academic performance. A previous study showed that students with lower than average performance tend to cheat 55 . Future research should control and study the links in a longitudinal data set. Finally, although the current research only focused on the impact of individual factors on academic misconduct, contextual factors could be considered using multi-level analysis.

Data availability

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due the present study is a part of a bigger study that has not been completed yet, but is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

McCabe, D. L. & Trevino, L. K. Individual and contextual influences on academic dishonesty: A multicampus investigation. Res. High. Educ. 38 , 379–396 (1997).

Article Google Scholar

Barrett, R. & Cox, A. L. ‘At least they’re learning something’: The hazy line between collaboration and collusion. Assess. Eval. High. Educ. 30 , 107–122 (2005).

Verhoef, A. H. & Coetser, Y. M. Academic integrity of university students during emergency. Transform. High. Educ. 6 , a132 (2021).

Google Scholar

Harding, T. S., Carpenter, D. D., Finelli, C. J. & Passow, H. J. Does academic dishonesty relate to unethical behavior in professional practice? An exploratory study. Sci. Eng. Ethics 10 , 311–324 (2004).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Orosz, G. et al. Academic cheating and time perspective: Cheaters live in the present instead of the future. Learn. Individ. Differ. 52 , 39–45 (2016).

Lawson, R. A. Is classroom cheating related to business students’ propensity to cheat in the “real world”?. J. Bus. Ethics 49 , 189–199 (2004).