- Open access

- Published: 27 November 2020

Designing process evaluations using case study to explore the context of complex interventions evaluated in trials

- Aileen Grant 1 ,

- Carol Bugge 2 &

- Mary Wells 3

Trials volume 21 , Article number: 982 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

11k Accesses

10 Citations

5 Altmetric

Metrics details

Process evaluations are an important component of an effectiveness evaluation as they focus on understanding the relationship between interventions and context to explain how and why interventions work or fail, and whether they can be transferred to other settings and populations. However, historically, context has not been sufficiently explored and reported resulting in the poor uptake of trial results. Therefore, suitable methodologies are needed to guide the investigation of context. Case study is one appropriate methodology, but there is little guidance about what case study design can offer the study of context in trials. We address this gap in the literature by presenting a number of important considerations for process evaluation using a case study design.

In this paper, we define context, the relationship between complex interventions and context, and describe case study design methodology. A well-designed process evaluation using case study should consider the following core components: the purpose; definition of the intervention; the trial design, the case, the theories or logic models underpinning the intervention, the sampling approach and the conceptual or theoretical framework. We describe each of these in detail and highlight with examples from recently published process evaluations.

Conclusions

There are a number of approaches to process evaluation design in the literature; however, there is a paucity of research on what case study design can offer process evaluations. We argue that case study is one of the best research designs to underpin process evaluations, to capture the dynamic and complex relationship between intervention and context during implementation. We provide a comprehensive overview of the issues for process evaluation design to consider when using a case study design.

Trial registration

DQIP - ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT01425502 - OPAL - ISRCTN57746448

Peer Review reports

Contribution to the literature

We illustrate how case study methodology can explore the complex, dynamic and uncertain relationship between context and interventions within trials.

We depict different case study designs and illustrate there is not one formula and that design needs to be tailored to the context and trial design.

Case study can support comparisons between intervention and control arms and between cases within arms to uncover and explain differences in detail.

We argue that case study can illustrate how components have evolved and been redefined through implementation.

Key issues for consideration in case study design within process evaluations are presented and illustrated with examples.

Process evaluations are an important component of an effectiveness evaluation as they focus on understanding the relationship between interventions and context to explain how and why interventions work or fail and whether they can be transferred to other settings and populations. However, historically, not all trials have had a process evaluation component, nor have they sufficiently reported aspects of context, resulting in poor uptake of trial findings [ 1 ]. Considerations of context are often absent from published process evaluations, with few studies acknowledging, taking account of or describing context during implementation, or assessing the impact of context on implementation [ 2 , 3 ]. At present, evidence from trials is not being used in a timely manner [ 4 , 5 ], and this can negatively impact on patient benefit and experience [ 6 ]. It takes on average 17 years for knowledge from research to be implemented into practice [ 7 ]. Suitable methodologies are therefore needed that allow for context to be exposed; one appropriate methodological approach is case study [ 8 , 9 ].

In 2015, the Medical Research Council (MRC) published guidance for process evaluations [ 10 ]. This was a key milestone in legitimising as well as providing tools, methods and a framework for conducting process evaluations. Nevertheless, as with all guidance, there is a need for reflection, challenge and refinement. There have been a number of critiques of the MRC guidance, including that interventions should be considered as events in systems [ 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 ]; a need for better use, critique and development of theories [ 15 , 16 , 17 ]; and a need for more guidance on integrating qualitative and quantitative data [ 18 , 19 ]. Although the MRC process evaluation guidance does consider appropriate qualitative and quantitative methods, it does not mention case study design and what it can offer the study of context in trials.

The case study methodology is ideally suited to real-world, sustainable intervention development and evaluation because it can explore and examine contemporary complex phenomena, in depth, in numerous contexts and using multiple sources of data [ 8 ]. Case study design can capture the complexity of the case, the relationship between the intervention and the context and how the intervention worked (or not) [ 8 ]. There are a number of textbooks on a case study within the social science fields [ 8 , 9 , 20 ], but there are no case study textbooks and a paucity of useful texts on how to design, conduct and report case study within the health arena. Few examples exist within the trial design and evaluation literature [ 3 , 21 ]. Therefore, guidance to enable well-designed process evaluations using case study methodology is required.

We aim to address the gap in the literature by presenting a number of important considerations for process evaluation using a case study design. First, we define the context and describe the relationship between complex health interventions and context.

What is context?

While there is growing recognition that context interacts with the intervention to impact on the intervention’s effectiveness [ 22 ], context is still poorly defined and conceptualised. There are a number of different definitions in the literature, but as Bate et al. explained ‘almost universally, we find context to be an overworked word in everyday dialogue but a massively understudied and misunderstood concept’ [ 23 ]. Ovretveit defines context as ‘everything the intervention is not’ [ 24 ]. This last definition is used by the MRC framework for process evaluations [ 25 ]; however; the problem with this definition is that it is highly dependent on how the intervention is defined. We have found Pfadenhauer et al.’s definition useful:

Context is conceptualised as a set of characteristics and circumstances that consist of active and unique factors that surround the implementation. As such it is not a backdrop for implementation but interacts, influences, modifies and facilitates or constrains the intervention and its implementation. Context is usually considered in relation to an intervention or object, with which it actively interacts. A boundary between the concepts of context and setting is discernible: setting refers to the physical, specific location in which the intervention is put into practice. Context is much more versatile, embracing not only the setting but also roles, interactions and relationships [ 22 ].

Traditionally, context has been conceptualised in terms of barriers and facilitators, but what is a barrier in one context may be a facilitator in another, so it is the relationship and dynamics between the intervention and context which are the most important [ 26 ]. There is a need for empirical research to really understand how different contextual factors relate to each other and to the intervention. At present, research studies often list common contextual factors, but without a depth of meaning and understanding, such as government or health board policies, organisational structures, professional and patient attitudes, behaviours and beliefs [ 27 ]. The case study methodology is well placed to understand the relationship between context and intervention where these boundaries may not be clearly evident. It offers a means of unpicking the contextual conditions which are pertinent to effective implementation.

The relationship between complex health interventions and context

Health interventions are generally made up of a number of different components and are considered complex due to the influence of context on their implementation and outcomes [ 3 , 28 ]. Complex interventions are often reliant on the engagement of practitioners and patients, so their attitudes, behaviours, beliefs and cultures influence whether and how an intervention is effective or not. Interventions are context-sensitive; they interact with the environment in which they are implemented. In fact, many argue that interventions are a product of their context, and indeed, outcomes are likely to be a product of the intervention and its context [ 3 , 29 ]. Within a trial, there is also the influence of the research context too—so the observed outcome could be due to the intervention alone, elements of the context within which the intervention is being delivered, elements of the research process or a combination of all three. Therefore, it can be difficult and unhelpful to separate the intervention from the context within which it was evaluated because the intervention and context are likely to have evolved together over time. As a result, the same intervention can look and behave differently in different contexts, so it is important this is known, understood and reported [ 3 ]. Finally, the intervention context is dynamic; the people, organisations and systems change over time, [ 3 ] which requires practitioners and patients to respond, and they may do this by adapting the intervention or contextual factors. So, to enable researchers to replicate successful interventions, or to explain why the intervention was not successful, it is not enough to describe the components of the intervention, they need to be described by their relationship to their context and resources [ 3 , 28 ].

What is a case study?

Case study methodology aims to provide an in-depth, holistic, balanced, detailed and complete picture of complex contemporary phenomena in its natural context [ 8 , 9 , 20 ]. In this case, the phenomena are the implementation of complex interventions in a trial. Case study methodology takes the view that the phenomena can be more than the sum of their parts and have to be understood as a whole [ 30 ]. It is differentiated from a clinical case study by its analytical focus [ 20 ].

The methodology is particularly useful when linked to trials because some of the features of the design naturally fill the gaps in knowledge generated by trials. Given the methodological focus on understanding phenomena in the round, case study methodology is typified by the use of multiple sources of data, which are more commonly qualitatively guided [ 31 ]. The case study methodology is not epistemologically specific, like realist evaluation, and can be used with different epistemologies [ 32 ], and with different theories, such as Normalisation Process Theory (which explores how staff work together to implement a new intervention) or the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (which provides a menu of constructs associated with effective implementation) [ 33 , 34 , 35 ]. Realist evaluation can be used to explore the relationship between context, mechanism and outcome, but case study differs from realist evaluation by its focus on a holistic and in-depth understanding of the relationship between an intervention and the contemporary context in which it was implemented [ 36 ]. Case study enables researchers to choose epistemologies and theories which suit the nature of the enquiry and their theoretical preferences.

Designing a process evaluation using case study

An important part of any study is the research design. Due to their varied philosophical positions, the seminal authors in the field of case study have different epistemic views as to how a case study should be conducted [ 8 , 9 ]. Stake takes an interpretative approach (interested in how people make sense of their world), and Yin has more positivistic leanings, arguing for objectivity, validity and generalisability [ 8 , 9 ].

Regardless of the philosophical background, a well-designed process evaluation using case study should consider the following core components: the purpose; the definition of the intervention, the trial design, the case, and the theories or logic models underpinning the intervention; the sampling approach; and the conceptual or theoretical framework [ 8 , 9 , 20 , 31 , 33 ]. We now discuss these critical components in turn, with reference to two process evaluations that used case study design, the DQIP and OPAL studies [ 21 , 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 , 41 ].

The purpose of a process evaluation is to evaluate and explain the relationship between the intervention and its components, to context and outcome. It can help inform judgements about validity (by exploring the intervention components and their relationship with one another (construct validity), the connections between intervention and outcomes (internal validity) and the relationship between intervention and context (external validity)). It can also distinguish between implementation failure (where the intervention is poorly delivered) and intervention failure (intervention design is flawed) [ 42 , 43 ]. By using a case study to explicitly understand the relationship between context and the intervention during implementation, the process evaluation can explain the intervention effects and the potential generalisability and optimisation into routine practice [ 44 ].

The DQIP process evaluation aimed to qualitatively explore how patients and GP practices responded to an intervention designed to reduce high-risk prescribing of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and/or antiplatelet agents (see Table 1 ) and quantitatively examine how change in high-risk prescribing was associated with practice characteristics and implementation processes. The OPAL process evaluation (see Table 2 ) aimed to quantitatively understand the factors which influenced the effectiveness of a pelvic floor muscle training intervention for women with urinary incontinence and qualitatively explore the participants’ experiences of treatment and adherence.

Defining the intervention and exploring the theories or assumptions underpinning the intervention design

Process evaluations should also explore the utility of the theories or assumptions underpinning intervention design [ 49 ]. Not all theories underpinning interventions are based on a formal theory, but they based on assumptions as to how the intervention is expected to work. These can be depicted as a logic model or theory of change [ 25 ]. To capture how the intervention and context evolve requires the intervention and its expected mechanisms to be clearly defined at the outset [ 50 ]. Hawe and colleagues recommend defining interventions by function (what processes make the intervention work) rather than form (what is delivered) [ 51 ]. However, in some cases, it may be useful to know if some of the components are redundant in certain contexts or if there is a synergistic effect between all the intervention components.

The DQIP trial delivered two interventions, one intervention was delivered to professionals with high fidelity and then professionals delivered the other intervention to patients by form rather than function allowing adaptations to the local context as appropriate. The assumptions underpinning intervention delivery were prespecified in a logic model published in the process evaluation protocol [ 52 ].

Case study is well placed to challenge or reinforce the theoretical assumptions or redefine these based on the relationship between the intervention and context. Yin advocates the use of theoretical propositions; these direct attention to specific aspects of the study for investigation [ 8 ] can be based on the underlying assumptions and tested during the course of the process evaluation. In case studies, using an epistemic position more aligned with Yin can enable research questions to be designed, which seek to expose patterns of unanticipated as well as expected relationships [ 9 ]. The OPAL trial was more closely aligned with Yin, where the research team predefined some of their theoretical assumptions, based on how the intervention was expected to work. The relevant parts of the data analysis then drew on data to support or refute the theoretical propositions. This was particularly useful for the trial as the prespecified theoretical propositions linked to the mechanisms of action on which the intervention was anticipated to have an effect (or not).

Tailoring to the trial design

Process evaluations need to be tailored to the trial, the intervention and the outcomes being measured [ 45 ]. For example, in a stepped wedge design (where the intervention is delivered in a phased manner), researchers should try to ensure process data are captured at relevant time points or in a two-arm or multiple arm trial, ensure data is collected from the control group(s) as well as the intervention group(s). In the DQIP trial, a stepped wedge trial, at least one process evaluation case, was sampled per cohort. Trials often continue to measure outcomes after delivery of the intervention has ceased, so researchers should also consider capturing ‘follow-up’ data on contextual factors, which may continue to influence the outcome measure. The OPAL trial had two active treatment arms so collected process data from both arms. In addition, as the trial was interested in long-term adherence, the trial and the process evaluation collected data from participants for 2 years after the intervention was initially delivered, providing 24 months follow-up data, in line with the primary outcome for the trial.

Defining the case

Case studies can include single or multiple cases in their design. Single case studies usually sample typical or unique cases, their advantage being the depth and richness that can be achieved over a long period of time. The advantages of multiple case study design are that cases can be compared to generate a greater depth of analysis. Multiple case study sampling may be carried out in order to test for replication or contradiction [ 8 ]. Given that trials are often conducted over a number of sites, a multiple case study design is more sensible for process evaluations, as there is likely to be variation in implementation between sites. Case definition may occur at a variety of levels but is most appropriate if it reflects the trial design. For example, a case in an individual patient level trial is likely to be defined as a person/patient (e.g. a woman with urinary incontinence—OPAL trial) whereas in a cluster trial, a case is like to be a cluster, such as an organisation (e.g. a general practice—DQIP trial). Of course, the process evaluation could explore cases with less distinct boundaries, such as communities or relationships; however, the clarity with which these cases are defined is important, in order to scope the nature of the data that will be generated.

Carefully sampled cases are critical to a good case study as sampling helps inform the quality of the inferences that can be made from the data [ 53 ]. In both qualitative and quantitative research, how and how many participants to sample must be decided when planning the study. Quantitative sampling techniques generally aim to achieve a random sample. Qualitative research generally uses purposive samples to achieve data saturation, occurring when the incoming data produces little or no new information to address the research questions. The term data saturation has evolved from theoretical saturation in conventional grounded theory studies; however, its relevance to other types of studies is contentious as the term saturation seems to be widely used but poorly justified [ 54 ]. Empirical evidence suggests that for in-depth interview studies, saturation occurs at 12 interviews for thematic saturation, but typically more would be needed for a heterogenous sample higher degrees of saturation [ 55 , 56 ]. Both DQIP and OPAL case studies were huge with OPAL designed to interview each of the 40 individual cases four times and DQIP designed to interview the lead DQIP general practitioner (GP) twice (to capture change over time), another GP and the practice manager from each of the 10 organisational cases. Despite the plethora of mixed methods research textbooks, there is very little about sampling as discussions typically link to method (e.g. interviews) rather than paradigm (e.g. case study).

Purposive sampling can improve the generalisability of the process evaluation by sampling for greater contextual diversity. The typical or average case is often not the richest source of information. Outliers can often reveal more important insights, because they may reflect the implementation of the intervention using different processes. Cases can be selected from a number of criteria, which are not mutually exclusive, to enable a rich and detailed picture to be built across sites [ 53 ]. To avoid the Hawthorne effect, it is recommended that process evaluations sample from both intervention and control sites, which enables comparison and explanation. There is always a trade-off between breadth and depth in sampling, so it is important to note that often quantity does not mean quality and that carefully sampled cases can provide powerful illustrative examples of how the intervention worked in practice, the relationship between the intervention and context and how and why they evolved together. The qualitative components of both DQIP and OPAL process evaluations aimed for maximum variation sampling. Please see Table 1 for further information on how DQIP’s sampling frame was important for providing contextual information on processes influencing effective implementation of the intervention.

Conceptual and theoretical framework

A conceptual or theoretical framework helps to frame data collection and analysis [ 57 ]. Theories can also underpin propositions, which can be tested in the process evaluation. Process evaluations produce intervention-dependent knowledge, and theories help make the research findings more generalizable by providing a common language [ 16 ]. There are a number of mid-range theories which have been designed to be used with process evaluation [ 34 , 35 , 58 ]. The choice of the appropriate conceptual or theoretical framework is, however, dependent on the philosophical and professional background of the research. The two examples within this paper used our own framework for the design of process evaluations, which proposes a number of candidate processes which can be explored, for example, recruitment, delivery, response, maintenance and context [ 45 ]. This framework was published before the MRC guidance on process evaluations, and both the DQIP and OPAL process evaluations were designed before the MRC guidance was published. The DQIP process evaluation explored all candidates in the framework whereas the OPAL process evaluation selected four candidates, illustrating that process evaluations can be selective in what they explore based on the purpose, research questions and resources. Furthermore, as Kislov and colleagues argue, we also have a responsibility to critique the theoretical framework underpinning the evaluation and refine theories to advance knowledge [ 59 ].

Data collection

An important consideration is what data to collect or measure and when. Case study methodology supports a range of data collection methods, both qualitative and quantitative, to best answer the research questions. As the aim of the case study is to gain an in-depth understanding of phenomena in context, methods are more commonly qualitative or mixed method in nature. Qualitative methods such as interviews, focus groups and observation offer rich descriptions of the setting, delivery of the intervention in each site and arm, how the intervention was perceived by the professionals delivering the intervention and the patients receiving the intervention. Quantitative methods can measure recruitment, fidelity and dose and establish which characteristics are associated with adoption, delivery and effectiveness. To ensure an understanding of the complexity of the relationship between the intervention and context, the case study should rely on multiple sources of data and triangulate these to confirm and corroborate the findings [ 8 ]. Process evaluations might consider using routine data collected in the trial across all sites and additional qualitative data across carefully sampled sites for a more nuanced picture within reasonable resource constraints. Mixed methods allow researchers to ask more complex questions and collect richer data than can be collected by one method alone [ 60 ]. The use of multiple sources of data allows data triangulation, which increases a study’s internal validity but also provides a more in-depth and holistic depiction of the case [ 20 ]. For example, in the DQIP process evaluation, the quantitative component used routinely collected data from all sites participating in the trial and purposively sampled cases for a more in-depth qualitative exploration [ 21 , 38 , 39 ].

The timing of data collection is crucial to study design, especially within a process evaluation where data collection can potentially influence the trial outcome. Process evaluations are generally in parallel or retrospective to the trial. The advantage of a retrospective design is that the evaluation itself is less likely to influence the trial outcome. However, the disadvantages include recall bias, lack of sensitivity to nuances and an inability to iteratively explore the relationship between intervention and outcome as it develops. To capture the dynamic relationship between intervention and context, the process evaluation needs to be parallel and longitudinal to the trial. Longitudinal methodological design is rare, but it is needed to capture the dynamic nature of implementation [ 40 ]. How the intervention is delivered is likely to change over time as it interacts with context. For example, as professionals deliver the intervention, they become more familiar with it, and it becomes more embedded into systems. The OPAL process evaluation was a longitudinal, mixed methods process evaluation where the quantitative component had been predefined and built into trial data collection systems. Data collection in both the qualitative and quantitative components mirrored the trial data collection points, which were longitudinal to capture adherence and contextual changes over time.

There is a lot of attention in the recent literature towards a systems approach to understanding interventions in context, which suggests interventions are ‘events within systems’ [ 61 , 62 ]. This framing highlights the dynamic nature of context, suggesting that interventions are an attempt to change systems dynamics. This conceptualisation would suggest that the study design should collect contextual data before and after implementation to assess the effect of the intervention on the context and vice versa.

Data analysis

Designing a rigorous analysis plan is particularly important for multiple case studies, where researchers must decide whether their approach to analysis is case or variable based. Case-based analysis is the most common, and analytic strategies must be clearly articulated for within and across case analysis. A multiple case study design can consist of multiple cases, where each case is analysed at the case level, or of multiple embedded cases, where data from all the cases are pulled together for analysis at some level. For example, OPAL analysis was at the case level, but all the cases for the intervention and control arms were pulled together at the arm level for more in-depth analysis and comparison. For Yin, analytical strategies rely on theoretical propositions, but for Stake, analysis works from the data to develop theory. In OPAL and DQIP, case summaries were written to summarise the cases and detail within-case analysis. Each of the studies structured these differently based on the phenomena of interest and the analytic technique. DQIP applied an approach more akin to Stake [ 9 ], with the cases summarised around inductive themes whereas OPAL applied a Yin [ 8 ] type approach using theoretical propositions around which the case summaries were structured. As the data for each case had been collected through longitudinal interviews, the case summaries were able to capture changes over time. It is beyond the scope of this paper to discuss different analytic techniques; however, to ensure the holistic examination of the intervention(s) in context, it is important to clearly articulate and demonstrate how data is integrated and synthesised [ 31 ].

There are a number of approaches to process evaluation design in the literature; however, there is a paucity of research on what case study design can offer process evaluations. We argue that case study is one of the best research designs to underpin process evaluations, to capture the dynamic and complex relationship between intervention and context during implementation [ 38 ]. Case study can enable comparisons within and across intervention and control arms and enable the evolving relationship between intervention and context to be captured holistically rather than considering processes in isolation. Utilising a longitudinal design can enable the dynamic relationship between context and intervention to be captured in real time. This information is fundamental to holistically explaining what intervention was implemented, understanding how and why the intervention worked or not and informing the transferability of the intervention into routine clinical practice.

Case study designs are not prescriptive, but process evaluations using case study should consider the purpose, trial design, the theories or assumptions underpinning the intervention, and the conceptual and theoretical frameworks informing the evaluation. We have discussed each of these considerations in turn, providing a comprehensive overview of issues for process evaluations using a case study design. There is no single or best way to conduct a process evaluation or a case study, but researchers need to make informed choices about the process evaluation design. Although this paper focuses on process evaluations, we recognise that case study design could also be useful during intervention development and feasibility trials. Elements of this paper are also applicable to other study designs involving trials.

Availability of data and materials

No data and materials were used.

Abbreviations

Data-driven Quality Improvement in Primary Care

Medical Research Council

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

Optimizing Pelvic Floor Muscle Exercises to Achieve Long-term benefits

Blencowe NB. Systematic review of intervention design and delivery in pragmatic and explanatory surgical randomized clinical trials. Br J Surg. 2015;102:1037–47.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Dixon-Woods M. The problem of context in quality improvement. In: Foundation TH, editor. Perspectives on context: The Health Foundation; 2014.

Wells M, Williams B, Treweek S, Coyle J, Taylor J. Intervention description is not enough: evidence from an in-depth multiple case study on the untold role and impact of context in randomised controlled trials of seven complex interventions. Trials. 2012;13(1):95.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Grant A, Sullivan F, Dowell J. An ethnographic exploration of influences on prescribing in general practice: why is there variation in prescribing practices? Implement Sci. 2013;8(1):72.

Lang ES, Wyer PC, Haynes RB. Knowledge translation: closing the evidence-to-practice gap. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;49(3):355–63.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Ward V, House AF, Hamer S. Developing a framework for transferring knowledge into action: a thematic analysis of the literature. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2009;14(3):156–64.

Morris ZS, Wooding S, Grant J. The answer is 17 years, what is the question: understanding time lags in translational research. J R Soc Med. 2011;104(12):510–20.

Yin R. Case study research and applications: design and methods. Los Angeles: Sage Publications Inc; 2018.

Google Scholar

Stake R. The art of case study research. Thousand Oaks, California: Sage Publications Ltd; 1995.

Moore GF, Audrey S, Barker M, Bond L, Bonell C, Hardeman W, Moore L, O’Cathain A, Tinati T, Wight D, et al. Process evaluation of complex interventions: Medical Research Council guidance. Br Med J. 2015;350.

Hawe P. Minimal, negligible and negligent interventions. Soc Sci Med. 2015;138:265–8.

Moore GF, Evans RE, Hawkins J, Littlecott H, Melendez-Torres GJ, Bonell C, Murphy S. From complex social interventions to interventions in complex social systems: future directions and unresolved questions for intervention development and evaluation. Evaluation. 2018;25(1):23–45.

Greenhalgh T, Papoutsi C. Studying complexity in health services research: desperately seeking an overdue paradigm shift. BMC Med. 2018;16(1):95.

Rutter H, Savona N, Glonti K, Bibby J, Cummins S, Finegood DT, Greaves F, Harper L, Hawe P, Moore L, et al. The need for a complex systems model of evidence for public health. Lancet. 2017;390(10112):2602–4.

Moore G, Cambon L, Michie S, Arwidson P, Ninot G, Ferron C, Potvin L, Kellou N, Charlesworth J, Alla F, et al. Population health intervention research: the place of theories. Trials. 2019;20(1):285.

Kislov R. Engaging with theory: from theoretically informed to theoretically informative improvement research. BMJ Qual Saf. 2019;28(3):177–9.

Boulton R, Sandall J, Sevdalis N. The cultural politics of ‘Implementation Science’. J Med Human. 2020;41(3):379-94. h https://doi.org/10.1007/s10912-020-09607-9 .

Cheng KKF, Metcalfe A. Qualitative methods and process evaluation in clinical trials context: where to head to? Int J Qual Methods. 2018;17(1):1609406918774212.

Article Google Scholar

Richards DA, Bazeley P, Borglin G, Craig P, Emsley R, Frost J, Hill J, Horwood J, Hutchings HA, Jinks C, et al. Integrating quantitative and qualitative data and findings when undertaking randomised controlled trials. BMJ Open. 2019;9(11):e032081.

Thomas G. How to do your case study, 2nd edition edn. London: Sage Publications Ltd; 2016.

Grant A, Dreischulte T, Guthrie B. Process evaluation of the Data-driven Quality Improvement in Primary Care (DQIP) trial: case study evaluation of adoption and maintenance of a complex intervention to reduce high-risk primary care prescribing. BMJ Open. 2017;7(3).

Pfadenhauer L, Rohwer A, Burns J, Booth A, Lysdahl KB, Hofmann B, Gerhardus A, Mozygemba K, Tummers M, Wahlster P, et al. Guidance for the assessment of context and implementation in health technology assessments (HTA) and systematic reviews of complex interventions: the Context and Implementation of Complex Interventions (CICI) framework: Integrate-HTA; 2016.

Bate P, Robert G, Fulop N, Ovretveit J, Dixon-Woods M. Perspectives on context. London: The Health Foundation; 2014.

Ovretveit J. Understanding the conditions for improvement: research to discover which context influences affect improvement success. BMJ Qual Saf. 2011;20.

Medical Research Council: Process evaluation of complex interventions: UK Medical Research Council (MRC) guidance. 2015.

May CR, Johnson M, Finch T. Implementation, context and complexity. Implement Sci. 2016;11(1):141.

Bate P. Context is everything. In: Perpesctives on Context. The Health Foundation 2014.

Horton TJ, Illingworth JH, Warburton WHP. Overcoming challenges in codifying and replicating complex health care interventions. Health Aff. 2018;37(2):191–7.

O'Connor AM, Tugwell P, Wells GA, Elmslie T, Jolly E, Hollingworth G, McPherson R, Bunn H, Graham I, Drake E. A decision aid for women considering hormone therapy after menopause: decision support framework and evaluation. Patient Educ Couns. 1998;33:267–79.

Creswell J, Poth C. Qualiative inquiry and research design, fourth edition edn. Thousan Oaks, California: Sage Publications; 2018.

Carolan CM, Forbat L, Smith A. Developing the DESCARTE model: the design of case study research in health care. Qual Health Res. 2016;26(5):626–39.

Takahashi ARW, Araujo L. Case study research: opening up research opportunities. RAUSP Manage J. 2020;55(1):100–11.

Tight M. Understanding case study research, small-scale research with meaning. London: Sage Publications; 2017.

May C, Finch T. Implementing, embedding, and integrating practices: an outline of normalisation process theory. Sociology. 2009;43:535.

Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice. A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4.

Pawson R, Tilley N. Realist evaluation. London: Sage; 1997.

Dreischulte T, Donnan P, Grant A, Hapca A, McCowan C, Guthrie B. Safer prescribing - a trial of education, informatics & financial incentives. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1053–64.

Grant A, Dreischulte T, Guthrie B. Process evaluation of the Data-driven Quality Improvement in Primary Care (DQIP) trial: active and less active ingredients of a multi-component complex intervention to reduce high-risk primary care prescribing. Implement Sci. 2017;12(1):4.

Dreischulte T, Grant A, Hapca A, Guthrie B. Process evaluation of the Data-driven Quality Improvement in Primary Care (DQIP) trial: quantitative examination of variation between practices in recruitment, implementation and effectiveness. BMJ Open. 2018;8(1):e017133.

Grant A, Dean S, Hay-Smith J, Hagen S, McClurg D, Taylor A, Kovandzic M, Bugge C. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness randomised controlled trial of basic versus biofeedback-mediated intensive pelvic floor muscle training for female stress or mixed urinary incontinence: protocol for the OPAL (Optimising Pelvic Floor Exercises to Achieve Long-term benefits) trial mixed methods longitudinal qualitative case study and process evaluation. BMJ Open. 2019;9(2):e024152.

Hagen S, McClurg D, Bugge C, Hay-Smith J, Dean SG, Elders A, Glazener C, Abdel-fattah M, Agur WI, Booth J, et al. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of basic versus biofeedback-mediated intensive pelvic floor muscle training for female stress or mixed urinary incontinence: protocol for the OPAL randomised trial. BMJ Open. 2019;9(2):e024153.

Steckler A, Linnan L. Process evaluation for public health interventions and research; 2002.

Durlak JA. Why programme implementation is so important. J Prev Intervent Commun. 1998;17(2):5–18.

Bonell C, Oakley A, Hargreaves J, VS, Rees R. Assessment of generalisability in trials of health interventions: suggested framework and systematic review. Br Med J. 2006;333(7563):346–9.

Article CAS Google Scholar

Grant A, Treweek S, Dreischulte T, Foy R, Guthrie B. Process evaluations for cluster-randomised trials of complex interventions: a proposed framework for design and reporting. Trials. 2013;14(1):15.

Yin R. Case study research: design and methods. London: Sage Publications; 2003.

Bugge C, Hay-Smith J, Grant A, Taylor A, Hagen S, McClurg D, Dean S: A 24 month longitudinal qualitative study of women’s experience of electromyography biofeedback pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT) and PFMT alone for urinary incontinence: adherence, outcome and context. ICS Gothenburg 2019 2019. https://www.ics.org/2019/abstract/473 . Access 10.9.2020.

Suzanne Hagen, Andrew Elders, Susan Stratton, Nicole Sergenson, Carol Bugge, Sarah Dean, Jean Hay-Smith, Mary Kilonzo, Maria Dimitrova, Mohamed Abdel-Fattah, Wael Agur, Jo Booth, Cathryn Glazener, Karen Guerrero, Alison McDonald, John Norrie, Louise R Williams, Doreen McClurg. Effectiveness of pelvic floor muscle training with and without electromyographic biofeedback for urinary incontinence in women: multicentre randomised controlled trial BMJ 2020;371. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m3719 .

Cook TD. Emergent principles for the design, implementation, and analysis of cluster-based experiments in social science. Ann Am Acad Pol Soc Sci. 2005;599(1):176–98.

Hoffmann T, Glasziou P, Boutron I, Milne R, Perera R, Moher D. Better reporting of interventions: template for intervention description and replication (TIDieR) checklist and guide. Br Med J. 2014;348.

Hawe P, Shiell A, Riley T. Complex interventions: how “out of control” can a randomised controlled trial be? Br Med J. 2004;328(7455):1561–3.

Grant A, Dreischulte T, Treweek S, Guthrie B. Study protocol of a mixed-methods evaluation of a cluster randomised trial to improve the safety of NSAID and antiplatelet prescribing: Data-driven Quality Improvement in Primary Care. Trials. 2012;13:154.

Flyvbjerg B. Five misunderstandings about case-study research. Qual Inq. 2006;12(2):219–45.

Thorne S. The great saturation debate: what the “S word” means and doesn’t mean in qualitative research reporting. Can J Nurs Res. 2020;52(1):3–5.

Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L. How many interviews are enough?: an experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods. 2006;18(1):59–82.

Guest G, Namey E, Chen M. A simple method to assess and report thematic saturation in qualitative research. PLoS One. 2020;15(5):e0232076.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Davidoff F, Dixon-Woods M, Leviton L, Michie S. Demystifying theory and its use in improvement. BMJ Qual Saf. 2015;24(3):228–38.

Rycroft-Malone J. The PARIHS framework: a framework for guiding the implementation of evidence-based practice. J Nurs Care Qual. 2004;4:297-304.

Kislov R, Pope C, Martin GP, Wilson PM. Harnessing the power of theorising in implementation science. Implement Sci. 2019;14(1):103.

Cresswell JW, Plano Clark VL. Designing and conducting mixed methods research. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications Ltd; 2007.

Hawe P, Shiell A, Riley T. Theorising interventions as events in systems. Am J Community Psychol. 2009;43:267–76.

Craig P, Ruggiero E, Frohlich KL, Mykhalovskiy E, White M. Taking account of context in population health intervention research: guidance for producers, users and funders of research: National Institute for Health Research; 2018. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK498645/pdf/Bookshelf_NBK498645.pdf .

Download references

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Professor Shaun Treweek for the discussions about context in trials.

No funding was received for this work.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Nursing, Midwifery and Paramedic Practice, Robert Gordon University, Garthdee Road, Aberdeen, AB10 7QB, UK

Aileen Grant

Faculty of Health Sciences and Sport, University of Stirling, Pathfoot Building, Stirling, FK9 4LA, UK

Carol Bugge

Department of Surgery and Cancer, Imperial College London, Charing Cross Campus, London, W6 8RP, UK

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

AG, CB and MW conceptualised the study. AG wrote the paper. CB and MW commented on the drafts. All authors have approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Aileen Grant .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

Ethics approval and consent to participate is not appropriate as no participants were included.

Consent for publication

Consent for publication is not required as no participants were included.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Grant, A., Bugge, C. & Wells, M. Designing process evaluations using case study to explore the context of complex interventions evaluated in trials. Trials 21 , 982 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-020-04880-4

Download citation

Received : 09 April 2020

Accepted : 06 November 2020

Published : 27 November 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-020-04880-4

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Process evaluation

- Case study design

ISSN: 1745-6215

- Submission enquiries: Access here and click Contact Us

- General enquiries: [email protected]

- Case Study Evaluation Approach

- Learning Center

A case study evaluation approach can be an incredibly powerful tool for monitoring and evaluating complex programs and policies. By identifying common themes and patterns, this approach allows us to better understand the successes and challenges faced by the program. In this article, we’ll explore the benefits of using a case study evaluation approach in the monitoring and evaluation of projects, programs, and public policies.

Table of Contents

Introduction to Case Study Evaluation Approach

The advantages of a case study evaluation approach, types of case studies, potential challenges with a case study evaluation approach, guiding principles for successful implementation of a case study evaluation approach.

- Benefits of Incorporating the Case Study Evaluation Approach in the Monitoring and Evaluation of Projects and Programs

A case study evaluation approach is a great way to gain an in-depth understanding of a particular issue or situation. This type of approach allows the researcher to observe, analyze, and assess the effects of a particular situation on individuals or groups.

An individual, a location, or a project may serve as the focal point of a case study’s attention. Quantitative and qualitative data are frequently used in conjunction with one another.

It also allows the researcher to gain insights into how people react to external influences. By using a case study evaluation approach, researchers can gain insights into how certain factors such as policy change or a new technology have impacted individuals and communities. The data gathered through this approach can be used to formulate effective strategies for responding to changes and challenges. Ultimately, this monitoring and evaluation approach helps organizations make better decision about the implementation of their plans.

This approach can be used to assess the effectiveness of a policy, program, or initiative by considering specific elements such as implementation processes, outcomes, and impact. A case study evaluation approach can provide an in-depth understanding of the effectiveness of a program by closely examining the processes involved in its implementation. This includes understanding the context, stakeholders, and resources to gain insight into how well a program is functioning or has been executed. By evaluating these elements, it can help to identify areas for improvement and suggest potential solutions. The findings from this approach can then be used to inform decisions about policies, programs, and initiatives for improved outcomes.

It is also useful for determining if other policies, programs, or initiatives could be applied to similar situations in order to achieve similar results or improved outcomes. All in all, the case study monitoring evaluation approach is an effective method for determining the effectiveness of specific policies, programs, or initiatives. By researching and analyzing the successes of previous cases, this approach can be used to identify similar approaches that could be applied to similar situations in order to achieve similar results or improved outcomes.

A case study evaluation approach offers the advantage of providing in-depth insight into a particular program or policy. This can be accomplished by analyzing data and observations collected from a range of stakeholders such as program participants, service providers, and community members. The monitoring and evaluation approach is used to assess the impact of programs and inform the decision-making process to ensure successful implementation. The case study monitoring and evaluation approach can help identify any underlying issues that need to be addressed in order to improve program effectiveness. It also provides a reality check on how successful programs are actually working, allowing organizations to make adjustments as needed. Overall, a case study monitoring and evaluation approach helps to ensure that policies and programs are achieving their objectives while providing valuable insight into how they are performing overall.

By taking a qualitative approach to data collection and analysis, case study evaluations are able to capture nuances in the context of a particular program or policy that can be overlooked when relying solely on quantitative methods. Using this approach, insights can be gleaned from looking at the individual experiences and perspectives of actors involved, providing a more detailed understanding of the impact of the program or policy than is possible with other evaluation methodologies. As such, case study monitoring evaluation is an invaluable tool in assessing the effectiveness of a particular initiative, enabling more informed decision-making as well as more effective implementation of programs and policies.

Furthermore, this approach is an effective way to uncover experiential information that can help to inform the ongoing improvement of policy and programming over time All in all, the case study monitoring evaluation approach offers an effective way to uncover experiential information necessary to inform the ongoing improvement of policy and programming. By analyzing the data gathered from this systematic approach, stakeholders can gain deeper insight into how best to make meaningful and long-term changes in their respective organizations.

Case studies come in a variety of forms, each of which can be put to a unique set of evaluation tasks. Evaluators have come to a consensus on describing six distinct sorts of case studies, which are as follows: illustrative, exploratory, critical instance, program implementation, program effects, and cumulative.

Illustrative Case Study

An illustrative case study is a type of case study that is used to provide a detailed and descriptive account of a particular event, situation, or phenomenon. It is often used in research to provide a clear understanding of a complex issue, and to illustrate the practical application of theories or concepts.

An illustrative case study typically uses qualitative data, such as interviews, surveys, or observations, to provide a detailed account of the unit being studied. The case study may also include quantitative data, such as statistics or numerical measurements, to provide additional context or to support the qualitative data.

The goal of an illustrative case study is to provide a rich and detailed description of the unit being studied, and to use this information to illustrate broader themes or concepts. For example, an illustrative case study of a successful community development project may be used to illustrate the importance of community engagement and collaboration in achieving development goals.

One of the strengths of an illustrative case study is its ability to provide a detailed and nuanced understanding of a particular issue or phenomenon. By focusing on a single case, the researcher is able to provide a detailed and in-depth analysis that may not be possible through other research methods.

However, one limitation of an illustrative case study is that the findings may not be generalizable to other contexts or populations. Because the case study focuses on a single unit, it may not be representative of other similar units or situations.

A well-executed case study can shed light on wider research topics or concepts through its thorough and descriptive analysis of a specific event or phenomenon.

Exploratory Case Study

An exploratory case study is a type of case study that is used to investigate a new or previously unexplored phenomenon or issue. It is often used in research when the topic is relatively unknown or when there is little existing literature on the topic.

Exploratory case studies are typically qualitative in nature and use a variety of methods to collect data, such as interviews, observations, and document analysis. The focus of the study is to gather as much information as possible about the phenomenon being studied and to identify new and emerging themes or patterns.

The goal of an exploratory case study is to provide a foundation for further research and to generate hypotheses about the phenomenon being studied. By exploring the topic in-depth, the researcher can identify new areas of research and generate new questions to guide future research.

One of the strengths of an exploratory case study is its ability to provide a rich and detailed understanding of a new or emerging phenomenon. By using a variety of data collection methods, the researcher can gather a broad range of data and perspectives to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the phenomenon being studied.

However, one limitation of an exploratory case study is that the findings may not be generalizable to other contexts or populations. Because the study is focused on a new or previously unexplored phenomenon, the findings may not be applicable to other situations or populations.

Exploratory case studies are an effective research strategy for learning about novel occurrences, developing research hypotheses, and gaining a deep familiarity with a topic of study.

Critical Instance Case Study

A critical instance case study is a type of case study that focuses on a specific event or situation that is critical to understanding a broader issue or phenomenon. The goal of a critical instance case study is to analyze the event in depth and to draw conclusions about the broader issue or phenomenon based on the analysis.

A critical instance case study typically uses qualitative data, such as interviews, observations, or document analysis, to provide a detailed and nuanced understanding of the event being studied. The data are analyzed using various methods, such as content analysis or thematic analysis, to identify patterns and themes that emerge from the data.

The critical instance case study is often used in research when a particular event or situation is critical to understanding a broader issue or phenomenon. For example, a critical instance case study of a successful disaster response effort may be used to identify key factors that contributed to the success of the response, and to draw conclusions about effective disaster response strategies more broadly.

One of the strengths of a critical instance case study is its ability to provide a detailed and in-depth analysis of a particular event or situation. By focusing on a critical instance, the researcher is able to provide a rich and nuanced understanding of the event, and to draw conclusions about broader issues or phenomena based on the analysis.

However, one limitation of a critical instance case study is that the findings may not be generalizable to other contexts or populations. Because the case study focuses on a specific event or situation, the findings may not be applicable to other similar events or situations.

A critical instance case study is a valuable research method that can provide a detailed and nuanced understanding of a particular event or situation and can be used to draw conclusions about broader issues or phenomena based on the analysis.

Program Implementation Program Implementation

A program implementation case study is a type of case study that focuses on the implementation of a particular program or intervention. The goal of the case study is to provide a detailed and comprehensive account of the program implementation process, and to identify factors that contributed to the success or failure of the program.

Program implementation case studies typically use qualitative data, such as interviews, observations, and document analysis, to provide a detailed and nuanced understanding of the program implementation process. The data are analyzed using various methods, such as content analysis or thematic analysis, to identify patterns and themes that emerge from the data.

The program implementation case study is often used in research to evaluate the effectiveness of a particular program or intervention, and to identify strategies for improving program implementation in the future. For example, a program implementation case study of a school-based health program may be used to identify key factors that contributed to the success or failure of the program, and to make recommendations for improving program implementation in similar settings.

One of the strengths of a program implementation case study is its ability to provide a detailed and comprehensive account of the program implementation process. By using qualitative data, the researcher is able to capture the complexity and nuance of the implementation process, and to identify factors that may not be captured by quantitative data alone.

However, one limitation of a program implementation case study is that the findings may not be generalizable to other contexts or populations. Because the case study focuses on a specific program or intervention, the findings may not be applicable to other programs or interventions in different settings.

An effective research tool, a case study of program implementation may illuminate the intricacies of the implementation process and point the way towards future enhancements.

Program Effects Case Study

A program effects case study is a research method that evaluates the effectiveness of a particular program or intervention by examining its outcomes or effects. The purpose of this type of case study is to provide a detailed and comprehensive account of the program’s impact on its intended participants or target population.

A program effects case study typically employs both quantitative and qualitative data collection methods, such as surveys, interviews, and observations, to evaluate the program’s impact on the target population. The data is then analyzed using statistical and thematic analysis to identify patterns and themes that emerge from the data.

The program effects case study is often used to evaluate the success of a program and identify areas for improvement. For example, a program effects case study of a community-based HIV prevention program may evaluate the program’s effectiveness in reducing HIV transmission rates among high-risk populations and identify factors that contributed to the program’s success.

One of the strengths of a program effects case study is its ability to provide a detailed and nuanced understanding of a program’s impact on its intended participants or target population. By using both quantitative and qualitative data, the researcher can capture both the objective and subjective outcomes of the program and identify factors that may have contributed to the outcomes.

However, a limitation of the program effects case study is that it may not be generalizable to other populations or contexts. Since the case study focuses on a particular program and population, the findings may not be applicable to other programs or populations in different settings.

A program effects case study is a good way to do research because it can give a detailed look at how a program affects the people it is meant for. This kind of case study can be used to figure out what needs to be changed and how to make programs that work better.

Cumulative Case Study

A cumulative case study is a type of case study that involves the collection and analysis of multiple cases to draw broader conclusions. Unlike a single-case study, which focuses on one specific case, a cumulative case study combines multiple cases to provide a more comprehensive understanding of a phenomenon.

The purpose of a cumulative case study is to build up a body of evidence through the examination of multiple cases. The cases are typically selected to represent a range of variations or perspectives on the phenomenon of interest. Data is collected from each case using a range of methods, such as interviews, surveys, and observations.

The data is then analyzed across cases to identify common themes, patterns, and trends. The analysis may involve both qualitative and quantitative methods, such as thematic analysis and statistical analysis.

The cumulative case study is often used in research to develop and test theories about a phenomenon. For example, a cumulative case study of successful community-based health programs may be used to identify common factors that contribute to program success, and to develop a theory about effective community-based health program design.

One of the strengths of the cumulative case study is its ability to draw on a range of cases to build a more comprehensive understanding of a phenomenon. By examining multiple cases, the researcher can identify patterns and trends that may not be evident in a single case study. This allows for a more nuanced understanding of the phenomenon and helps to develop more robust theories.

However, one limitation of the cumulative case study is that it can be time-consuming and resource-intensive to collect and analyze data from multiple cases. Additionally, the selection of cases may introduce bias if the cases are not representative of the population of interest.

In summary, a cumulative case study is a valuable research method that can provide a more comprehensive understanding of a phenomenon by examining multiple cases. This type of case study is particularly useful for developing and testing theories and identifying common themes and patterns across cases.

When conducting a case study evaluation approach, one of the main challenges is the need to establish a contextually relevant research design that accounts for the unique factors of the case being studied. This requires close monitoring of the case, its environment, and relevant stakeholders. In addition, the researcher must build a framework for the collection and analysis of data that is able to draw meaningful conclusions and provide valid insights into the dynamics of the case. Ultimately, an effective case study monitoring evaluation approach will allow researchers to form an accurate understanding of their research subject.

Additionally, depending on the size and scope of the case, there may be concerns regarding the availability of resources and personnel that could be allocated to data collection and analysis. To address these issues, a case study monitoring evaluation approach can be adopted, which would involve a mix of different methods such as interviews, surveys, focus groups and document reviews. Such an approach could provide valuable insights into the effectiveness and implementation of the case in question. Additionally, this type of evaluation can be tailored to the specific needs of the case study to ensure that all relevant data is collected and respected.

When dealing with a highly sensitive or confidential subject matter within a case study, researchers must take extra measures to prevent bias during data collection as well as protect participant anonymity while also collecting valid data in order to ensure reliable results

Moreover, when conducting a case study evaluation it is important to consider the potential implications of the data gathered. By taking extra measures to prevent bias and protect participant anonymity, researchers can ensure reliable results while also collecting valid data. Maintaining confidentiality and deploying ethical research practices are essential when conducting a case study to ensure an unbiased and accurate monitoring evaluation.

When planning and implementing a case study evaluation approach, it is important to ensure the guiding principles of research quality, data collection, and analysis are met. To ensure these principles are upheld, it is essential to develop a comprehensive monitoring and evaluation plan. This plan should clearly outline the steps to be taken during the data collection and analysis process. Furthermore, the plan should provide detailed descriptions of the project objectives, target population, key indicators, and timeline. It is also important to include metrics or benchmarks to monitor progress and identify any potential areas for improvement. By implementing such an approach, it will be possible to ensure that the case study evaluation approach yields valid and reliable results.

To ensure successful implementation, it is essential to establish a reliable data collection process that includes detailed information such as the scope of the study, the participants involved, and the methods used to collect data. Additionally, it is important to have a clear understanding of what will be examined through the evaluation process and how the results will be used. All in all, it is essential to establish a sound monitoring evaluation approach for a successful case study implementation. This includes creating a reliable data collection process that encompasses the scope of the study, the participants involved, and the methods used to collect data. It is also imperative to have an understanding of what will be examined and how the results will be utilized. Ultimately, effective planning is key to ensure that the evaluation process yields meaningful insights.

Benefits of Incorporating the Case Study Evaluation Approach in the Monitoring and Evaluation of Projects and Programmes

Using a case study approach in monitoring and evaluation allows for a more detailed and in-depth exploration of the project’s success, helping to identify key areas of improvement and successes that may have been overlooked through traditional evaluation. Through this case study method, specific data can be collected and analyzed to identify trends and different perspectives that can support the evaluation process. This data can allow stakeholders to gain a better understanding of the project’s successes and failures, helping them make informed decisions on how to strengthen current activities or shape future initiatives. From a monitoring and evaluation standpoint, this approach can provide an increased level of accuracy in terms of accurately assessing the effectiveness of the project.

This can provide valuable insights into what works—and what doesn’t—when it comes to implementing projects and programs, aiding decision-makers in making future plans that better meet their objectives However, monitoring and evaluation is just one approach to assessing the success of a case study. It does provide a useful insight into what initiatives may be successful, but it is important to note that there are other effective research methods, such as surveys and interviews, that can also help to further evaluate the success of a project or program.

In conclusion, a case study evaluation approach can be incredibly useful in monitoring and evaluating complex programs and policies. By exploring key themes, patterns and relationships, organizations can gain a detailed understanding of the successes, challenges and limitations of their program or policy. This understanding can then be used to inform decision-making and improve outcomes for those involved. With its ability to provide an in-depth understanding of a program or policy, the case study evaluation approach has become an invaluable tool for monitoring and evaluation professionals.

Leave a Comment Cancel Reply

Your email address will not be published.

Login with your Social Account

How strong is my resume.

Only 2% of resumes land interviews.

Land a better, higher-paying career

Jobs for You

Business development associate.

- United States

Director of Finance and Administration

- Bosnia and Herzegovina

Request for Information – Collecting Information on Potential Partners for Local Works Evaluation

- Washington, USA

Principal Field Monitors

Technical expert (health, wash, nutrition, education, child protection, hiv/aids, supplies), survey expert, data analyst, team leader, usaid-bha performance evaluation consultant.

- International Rescue Committee

Manager II, Institutional Support Program Implementation

Senior human resources associate, energy and environment analyst – usaid bureau for latin america and the caribbean, intern- international project and proposal support, ispi, deputy chief of party, senior accounting associate, services you might be interested in, useful guides ....

How to Create a Strong Resume

Monitoring And Evaluation Specialist Resume

Resume Length for the International Development Sector

Types of Evaluation

Monitoring, Evaluation, Accountability, and Learning (MEAL)

LAND A JOB REFERRAL IN 2 WEEKS (NO ONLINE APPS!)

Sign Up & To Get My Free Referral Toolkit Now:

- Contact sales

Start free trial

Project Evaluation Process: Definition, Methods & Steps

Managing a project with copious moving parts can be challenging to say the least, but project evaluation is designed to make the process that much easier. Every project starts with careful planning —t his sets the stage for the execution phase of the project while estimations, plans and schedules guide the project team as they complete tasks and deliverables.

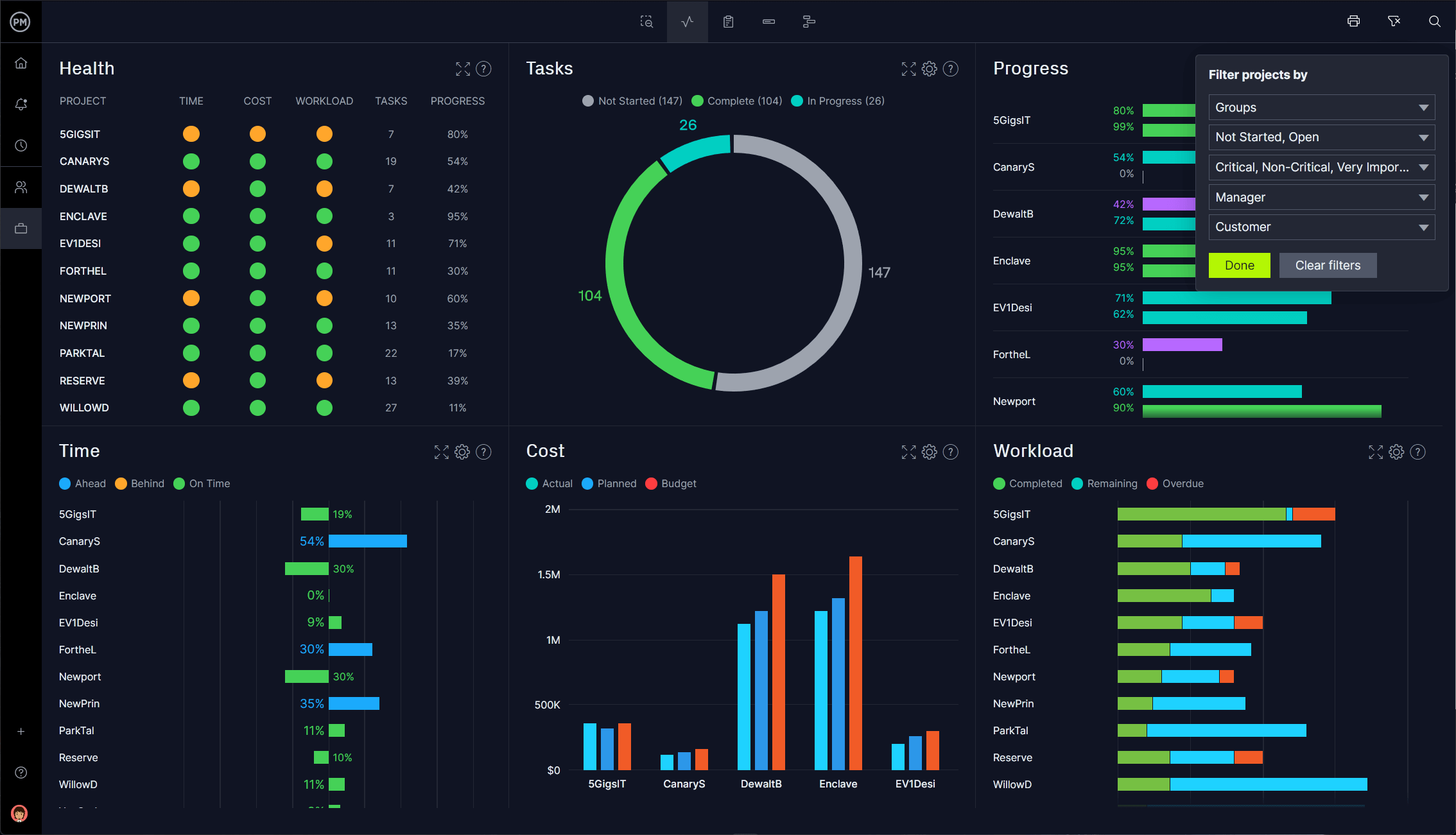

But even with the project evaluation process in place, managing a project successfully is not as simple as it sounds. Project managers need to keep track of costs , tasks and time during the entire project life cycle to make sure everything goes as planned. To do so, they utilize the project evaluation process and make use of project management software to help manage their team’s work in addition to planning and evaluating project performance.

What Is Project Evaluation?

Project evaluation is the process of measuring the success of a project, program or portfolio . This is done by gathering data about the project and using an evaluation method that allows evaluators to find performance improvement opportunities. Project evaluation is also critical to keep stakeholders updated on the project status and any changes that might be required to the budget or schedule.

Every aspect of the project such as costs, scope, risks or return on investment (ROI) is measured to determine if it’s proceeding as planned. If there are road bumps, this data can inform how projects can improve. Basically, you’re asking the project a series of questions designed to discover what is working, what can be improved and whether the project is useful. Tools such as project dashboards and trackers help in the evaluation process by making key data readily available.

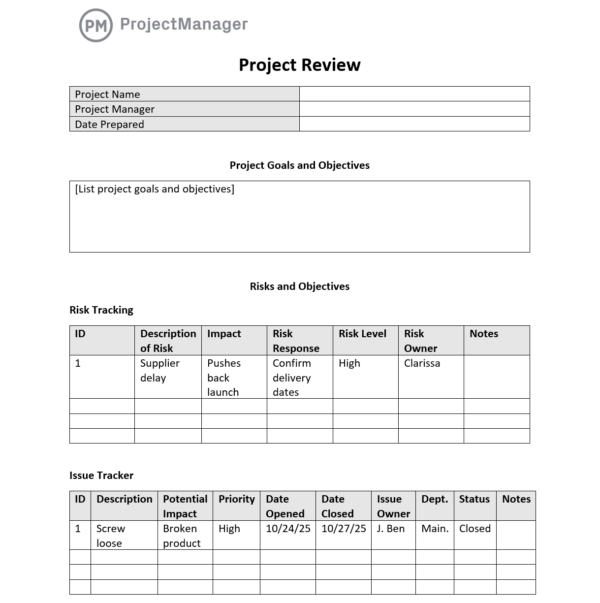

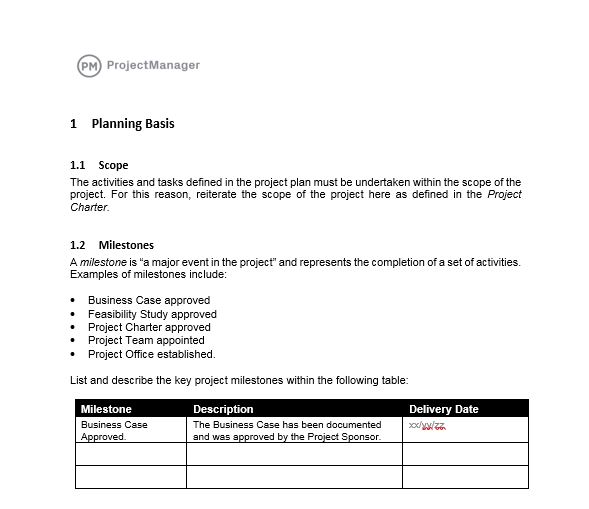

Get your free

Project Review Template

Use this free Project Review Template for Word to manage your projects better.

The project evaluation process has been around as long as projects themselves. But when it comes to the science of project management , project evaluation can be broken down into three main types or methods: pre-project evaluation, ongoing evaluation and post-project evaluation. Let’s look at the project evaluation process, what it entails and how you can improve your technique.

Project Evaluation Criteria

The specific details of the project evaluation criteria vary from one project or one organization to another. In general terms, a project evaluation process goes over the project constraints including time, cost, scope, resources, risk and quality. In addition, organizations may add their own business goals, strategic objectives and other project metrics .

Project Evaluation Methods

There are three points in a project where evaluation is most needed. While you can evaluate your project at any time, these are points where you should have the process officially scheduled.

1. Pre-Project Evaluation

In a sense, you’re pre-evaluating your project when you write your project charter to pitch to the stakeholders. You cannot effectively plan, staff and control a new project if you’ve first not evaluated it. Pre-project evaluation is the only sure way you can determine the effectiveness of the project before executing it.

2. Ongoing Project Evaluation

To make sure your project is proceeding as planned and hitting all of the scheduling and budget milestones you’ve set, it’s crucial that you constantly monitor and report on your work in real-time. Only by using project metrics can you measure the success of your project and whether or not you’re meeting the project’s goals and objectives. It’s strongly recommended that you use project management dashboards and tracking tools for ongoing evaluation.

Related: Free Project Dashboard Template for Excel

3. Post-Project Evaluation

Think of this as a postmortem. Post-project evaluation is when you go through the project’s paperwork, interview the project team and principles and analyze all relevant data so you can understand what worked and what went wrong. Only by developing this clear picture can you resolve issues in upcoming projects.

Free Project Review Template for Word

The project review template for Word is the perfect way to evaluate your project, whether it’s an ongoing project evaluation or post-project. It takes a holistic approach to project evaluation and covers such areas as goals, risks, staffing, resources and more. Download yours today.

Project Evaluation Steps

Regardless of when you choose to run a project evaluation, the process always has four phases: planning, implementation, completion and dissemination of reports.

1. Planning

The ultimate goal of this step is to create a project evaluation plan, a document that explains all details of your organization’s project evaluation process. When planning for a project evaluation, it’s important to identify the stakeholders and what their short-and-long-term goals are. You must make sure that your goals and objectives for the project are clear, and it’s critical to have settled on criteria that will tell you whether these goals and objects are being met.

So, you’ll want to write a series of questions to pose to the stakeholders. These queries should include subjects such as the project framework, best practices and metrics that determine success.

By including the stakeholders in your project evaluation plan, you’ll receive direction during the course of the project while simultaneously developing a relationship with the stakeholders. They will get progress reports from you throughout the project life cycle , and by building this initial relationship, you’ll likely earn their belief that you can manage the project to their satisfaction.

2. Implementation

While the project is running, you must monitor all aspects to make sure you’re meeting the schedule and budget. One of the things you should monitor during the project is the percentage completed. This is something you should do when creating status reports and meeting with your team. To make sure you’re on track, hold the team accountable for delivering timely tasks and maintain baseline dates to know when tasks are due.

Don’t forget to keep an eye on quality. It doesn’t matter if you deliver the project within the allotted time frame if the product is poor. Maintain quality reviews, and don’t delegate that responsibility. Instead, take it on yourself.

Maintaining a close relationship with the project budget is just as important as tracking the schedule and quality. Keep an eye on costs. They will fluctuate throughout the project, so don’t panic. However, be transparent if you notice a need growing for more funds. Let your steering committee know as soon as possible, so there are no surprises.

3. Completion

When you’re done with your project, you still have work to do. You’ll want to take the data you gathered in the evaluation and learn from it so you can fix problems that you discovered in the process. Figure out the short- and long-term impacts of what you learned in the evaluation.

4. Reporting and Disseminating

Once the evaluation is complete, you need to record the results. To do so, you’ll create a project evaluation report, a document that provides lessons for the future. Deliver your report to your stakeholders to keep them updated on the project’s progress.

How are you going to disseminate the report? There might be a protocol for this already established in your organization. Perhaps the stakeholders prefer a meeting to get the results face-to-face. Or maybe they prefer PDFs with easy-to-read charts and graphs. Make sure that you know your audience and tailor your report to them.

Benefits of Project Evaluation