1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

Philosophy, One Thousand Words at a Time

Happiness: What is it to be Happy?

Author: Kiki Berk Category: Ethics , Phenomenology and Existentialism Words: 992

Listen here

Do you want to be happy? If you’re like most people, then yes, you do.

But what is happiness? What does it mean to be “happy”? [1]

This essay discusses four major philosophical theories of happiness. [2]

1. Hedonism

According to hedonism, happiness is simply the experience of pleasure. [3] A happy person has a lot more pleasure than displeasure (pain) in her life. To be happy, then, is just to feel good. In other words, there’s no difference between being happy and feeling happy.

Famous hedonists include the ancient Greek philosopher Epicurus and the modern English philosophers Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill. [4] These philosophers all took happiness to include intellectual pleasures (such as reading a book) in addition to physical pleasures (such as having sex).

Although we associate being happy with feeling good, many philosophers think that hedonism is mistaken.

First, it’s possible to be happy without feeling good (such as when a happy person has a toothache), and it’s also possible to feel good without being happy (such as when an unhappy person gets a massage). Since happiness and pleasure can come apart, they can’t be the same thing.

Second, happiness and pleasure seem to have different properties. Pleasures are often fleeting, simple, and superficial (think of the pleasure involved in eating ice cream), whereas happiness is supposed to be lasting, complex, and profound. Things with different properties can’t be identical, so happiness can’t be the same thing as pleasure.

These arguments suggest that happiness and pleasure aren’t identical. That being said, it’s hard to imagine a happy person who never feels good. So, perhaps happiness involves pleasure without being identical to it.

2. Virtue Theory

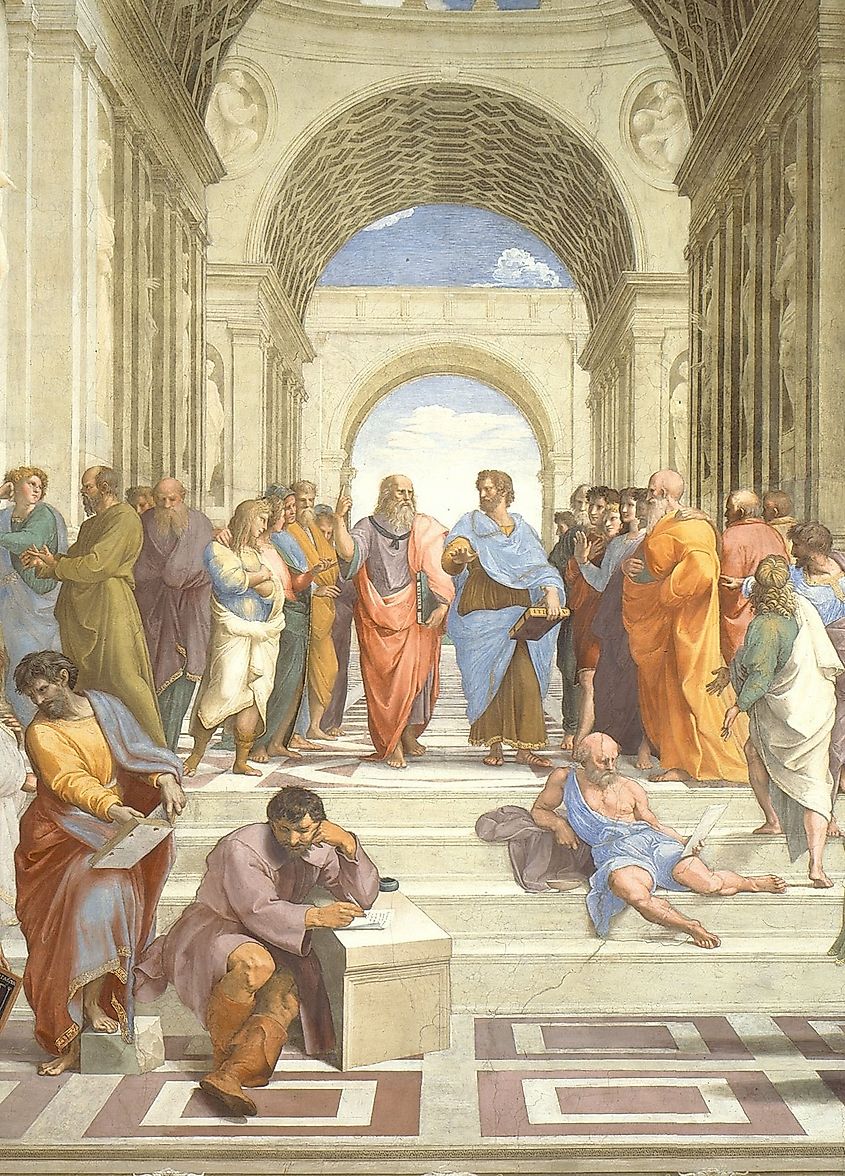

According to virtue theory, happiness is the result of cultivating the virtues—both moral and intellectual—such as wisdom, courage, temperance, and patience. A happy person must be sufficiently virtuous. To be happy, then, is to cultivate excellence and to flourish as a result. This view is famously held by Plato, Aristotle, and the Stoics. [5]

Linking happiness to virtue has the advantage of treating happiness as a lasting, complex, and profound phenomenon. It also explains how happiness and pleasure can come apart, since a person can be virtuous without feeling good, and a person can feel good without being virtuous.

In spite of these advantages, however, virtue theory is questionable. An important part of being virtuous is being morally good. But are immoral people always unhappy? Arguably not. Many bad people seem happy in spite of—or even because of—their unsavory actions. And a similar point can be made about intellectual virtue: unwise or irrational people aren’t always unhappy, either. In fact, some of these people seem happy as a direct result of their intellectual deficiencies. “Ignorance is bliss,” the saying goes!

But virtue theorists have a response here. Maybe some immoral people seem happy, on the surface; but that doesn’t mean that they are truly happy, at some deeper level. And the same thing can be said about people who lack the intellectual virtues: ignorance may lead to bliss, but that bliss isn’t true happiness. So, there seems to be some room for debate on these issues.

3. Desire Satisfaction Theory

According to the desire satisfaction theory, happiness consists in getting what you want—whatever that happens to be. A happy person has many of her desires satisfied; and the more her desires are satisfied, the happier she is.

Even though getting what you want can be a source of happiness, identifying happiness with desire satisfaction is problematic.

To start, this implies that the only way to become happier is by satisfying a desire. This seems wrong. Sometimes our happiness is increased by getting something we didn’t previously want—such as a surprise birthday party or getting stuck taking care of a neighbor’s cat. This implies that desire satisfaction is not necessary for happiness.

Desire satisfaction is not always sufficient for happiness, either. Unfortunately, it is common for people to feel disappointed when they get what they want. Many accomplishments, such as earning a degree or winning a tournament, simply don’t bring the long-lasting happiness that we expect. [6]

So, even if getting what we want sometimes makes us happy, these counterexamples suggest that happiness does not consist in desire satisfaction. [7]

4. Life Satisfaction Theory

According to the life satisfaction theory, happiness consists in being satisfied with your life. A happy person has a positive impression of her life in general, even though she might not be happy about every single aspect of it. To be happy, then, means to be content with your life as a whole.

It’s controversial whether life satisfaction is affective (a feeling) or cognitive (a belief). On the one hand, life satisfaction certainly comes with positive feelings. On the other hand, it’s possible to step back, reflect on your life, and realize that it’s good, even when you’re feeling down. [8]

One problem for this theory is that it’s difficult for people to distinguish how they feel in the moment from how they feel about their lives overall. Studies have shown that people report feeling more satisfied with their lives when the weather is good, even though this shouldn’t make that much of a difference. But measuring life satisfaction is complicated, so perhaps such studies should be taken with a grain of salt. [9]

5. Conclusion

Understanding what happiness is should enable you to become happier.

First, decide which theory of happiness you think is true, based on the arguments.

Second, pursue whatever happiness is according to that theory: seek pleasure and try to avoid pain (hedonism), cultivate moral and intellectual virtue (virtue theory), decide what you really want and do your best to get it (desire satisfaction theory), or change your life (or your attitude about it) so you feel (or believe) that it’s going well (life satisfaction theory).

And if you’re not sure which theory of happiness is true, then you could always try pursuing all of these things. 😊

[1] This might seem like an empirical (scientific) question rather than a philosophical one. However, this essay asks the conceptual question of what happiness is, and conceptual questions belong to philosophy, not to science.

[2] Happiness is commonly distinguished from “well-being,” i.e., the state of a life that is worth living. Whether or not happiness is the same thing as well-being is an open question, but most philosophers think it isn’t. See, for example, Haybron (2020).

[3] The word “hedonism” has different uses in philosophy. In this paper, it means that happiness is the same thing as pleasure (hedonism about happiness). But sometimes it is used to mean that happiness is the only thing that has intrinsic value (hedonism about value) or that humans are always and only motivated by pleasure (psychological hedonism). It’s important not to confuse these different uses of the word.

[4] For more on Epicurus and happiness, see Konstan (2018). For more on Bentham and Mill on happiness, see Driver (2014), as well as John Stuart Mill on The Good Life: Higher-Quality Pleasures by Dale E. Miller and Consequentialism by Shane Gronholz

[5] For more on Plato and happiness, see Frede (2017); for more on Aristotle and happiness, see Kraut (2018), and on the Stoics and happiness, see Baltzly (2019).

[6] For a discussion of the phenomenon of disappointment in this context see, for example, Ben Shahar (2007).

[7] For more objections to the desire satisfaction theory, see Shafer-Landau (2018) and Vitrano (2013).

[8] If happiness is life satisfaction, then happiness seems to be “subjective” in the sense that a person cannot be mistaken about whether or not she is happy. Whether happiness is subjective in this sense is controversial, and a person who thinks that a person can be mistaken about whether or not she is happy will probably favor a different theory of happiness.

[9] See Weimann, Knabe and Schob (2015) and Berk (2018).

Baltzly, Dirk, “Stoicism”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2019 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2019/entries/stoicism/>.

Berk, Kiki (2018). “Does Money Make Us Happy? The Prospects and Problems of Happiness Research in Economics,” in Journal of Happiness Studies, 19, 1241-1245.

Ben-Shahar, Tal (2007). Happier . New York: McGraw-Hill.

Driver, Julia, “The History of Utilitarianism”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2014 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2014/entries/utilitarianism-history/>.

Frede, Dorothea, “Plato’s Ethics: An Overview”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2017 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2017/entries/plato-ethics/>.

Haybron, Dan, “Happiness”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2020 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2020/entries/happiness/>.

Konstan, David, “Epicurus”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2018 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2018/entries/epicurus/>.

Kraut, Richard, “Aristotle’s Ethics”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2018 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2018/entries/aristotle-ethics/>.

Shafer-Landau, Russ (2018). The Ethical Life: Fundamental Readings in Ethics and Moral Problems. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Vitrano, Christine (2013). The Nature and Value of Happiness. Boulder: Westview Press.

Weimann, Joachim, Andreas Knabe, and Ronnie Schob (2015). Measuring Happiness . Cambridge: The MIT Press.

Related Essays

Meaning in Life: What Makes Our Lives Meaningful? by Matthew Pianalto

The Philosophy of Humor: What Makes Something Funny? by Chris A. Kramer

Virtue Ethics by David Merry

John Stuart Mill on The Good Life: Higher-Quality Pleasures by Dale E. Miller

Consequentialism by Shane Gronholz

Ethical Egoism by Nathan Nobis

Ancient Cynicism: Rejecting Civilization and Returning to Nature by G. M. Trujillo, Jr.

What Is It To Love Someone? by Felipe Pereira

Camus on the Absurd: The Myth of Sisyphus by Erik Van Aken

Ethics and Absolute Poverty: Peter Singer and Effective Altruism by Brandon Boesch

Is Death Bad? Epicurus and Lucretius on the Fear of Death by Frederik Kaufman

PDF Download

Download this essay in PDF .

About the Author

Dr. Kiki Berk is an Associate Professor of Philosophy at Southern New Hampshire University. She received her Ph.D. in Philosophy from the VU University Amsterdam in 2010. Her research focuses on Beauvoir’s and Sartre’s philosophies of death and meaning in life.

Follow 1000-Word Philosophy on Facebook , Twitter and subscribe to receive email notifications of new essays at the bottom of 1000WordPhilosophy.com

Share this:, 20 thoughts on “ happiness: what is it to be happy ”.

- Pingback: Ancient Cynicism: Rejecting Civilization and Returning to Nature – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: W.D. Ross’s Ethics of “Prima Facie” Duties – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Aristotle on Friendship: What Does It Take to Be a Good Friend? – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: The Philosophy of Humor: What Makes Something Funny? – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Meaning in Life: What Makes Our Lives Meaningful? – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Virtue Ethics – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Is Death Bad? Epicurus and Lucretius on the Fear of Death – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Reason is the Slave to the Passions: Hume on Reason vs. Desire – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Online Philosophy Resources Weekly Update | Daily Nous

- Pingback: Is Immortality Desirable? – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Ethics and Absolute Poverty: Peter Singer and Effective Altruism – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: What Is It To Love Someone? – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Ethical Egoism – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Mill’s Proof of the Principle of Utility – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Consequentialism – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: John Stuart Mill on The Good Life: Higher-Quality Pleasures – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Hope – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Existentialism – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

- Pingback: Camus on the Absurd: The Myth of Sisyphus – 1000-Word Philosophy: An Introductory Anthology

Comments are closed.

- Corrections

How to Be Happy According to Plato

Achieving happiness is a commonly shared goal. What did Plato, one of history’s most renowned philosophers, think about how to become a happy person?

Human happiness has long been discussed throughout history, from scientists looking at the happiness receptors in our brains all the way through to philosophizing about human nature and purpose. Yet perhaps the most important and long-lasting ideas about human happiness date back 1000s of years to the ancient Greeks, especially the young Athenian philosopher, Plato. Plato’s teachings on human nature and happiness continue to shape western philosophical thought and modern science today.

Who was Plato?

Plato was arguably one of the most infamous ancient Greek philosophers to have lived in his time (and beyond). As the eager student of Socrates and the astute teacher of Aristotle , Plato would write down and record the lessons and conversations exchanged with his wise teachers and peers, which has played a crucial role in the history and evidencing of ancient Greek philosophical thought.

More than 2000 years ago, when Plato founded and opened his school, The Academy , he expanded the scope of philosophical ideas by creating a place where Athenian men could theorize about the deepest questions of the age, one of which was how to reach human happiness.

Happiness, Nature and Society Are All Interconnected

Get the latest articles delivered to your inbox

Please check your inbox to activate your subscription.

Questions about human nature and happiness were integral to Plato’s teachings, who believed that happiness, nature, beauty and society were all interconnected and each served a purpose in our ability to flourish and live fulfilled lives.

In his book, The Republic , Plato argues that only when we truly understand human nature can we find individual happiness and social stability. He also emphasized that humans are not self-sufficient but in fact benefit greatly from social interaction and friendships.

However, happiness itself was not dependent on external affairs, society or friendships. For Plato, the quest to find individual happiness ran parallel to the quest to control our inner self, namely our temptations, desires and emotions.

“The man who makes everything that leads to happiness depends upon himself, and not upon other men, has adopted the very best plan for living happily” Plato, The Republic

The Charioteer and His Two Horses

In his book of teachings, The Phaedrus, Plato used monologues, plays and allegories to express his ideas of happiness. Plato’s allegory of The Charioteer and His Two Horses is possibly his most important teaching on how to achieve inner happiness…

Imagine a charioteer is holding the steeds of two horses as he attempts to move his carriage forward along a path ahead.

One of these horses is a wild horse, described by Plato as a “crooked lumbering animal, put together anyhow…of a dark color, with grey eyes and blood-red complexion; the mate of insolence and pride, shag-eared and deaf, hardly yielding to whip and spur.” – Plato, The Phaedrus

The second horse is a noble horse, it is “upright and cleanly made…his color is white, and his eyes dark; he is a lover of honor and modesty and temperance, and the follower of true glory; he needs no touch of the whip, but is guided by word and admonition only.” – Plato, The Phaedrus

To the charioteers discontent, the wild horse is more interested in instant pleasures than moving forward, constantly tempted and distracted by food, sex, sleep and other physical desires. This horse makes it difficult for the charioteer to travel with ease.

The noble horse on the other hand, motivated by glory and victory, stays on track like it has been trained to do. Of course, this horse also has desires, temptations and emotions to contend with, and just like the wild horse, could lead the charioteer astray. However, the charioteer has instilled good habits and training to help the noble horse avoid distractions. As long as these good habits are firmly instilled and second nature to the noble horse, it will find pleasure in staying on track and travel forward with ease.

The Wild Horse Cannot be Trained, but it can be Controlled; The Noble Horse can be Trained, but it Needs Reasoning and Good Habits

For Plato, the wild horse represents the hedonistic pleasures and appetites that are shared by humans and animals alike. This horse cannot be trained since it merely acts instinctively and no amount of reason or rationality will divert its attention away from temptation.

Instead, the charioteer must be wise, it must avoid all temptations in its path in order to stay in control of the wild horse.

The noble horse represents the way in which we can live a virtuous life , even when emotions and desires might threaten to throw us off track. With the right amount of understanding and the cultivation of good habits, we can travel forward along our path with ease.

Plato acknowledges that it is in our human nature to have conflicting thoughts, desires and emotions, but we can train ourselves to take pleasure in the things that take us naturally along the right pathway.

As the charioteer moves forward along his path with a hand on each steed, he must understand his two horses and their inner tendencies and desires. He must understand what may lead them astray or pull them in different directions.

Only with this knowledge can he propel forward with control, ease and efficiency. With distractions out of sight and good habits instilled, the charioteer is aligned with the path ahead, and in this he will find happiness.

Happiness and Harnessing Control of Our Minds

The Charioteer and His Two Horses highlights that human beings must navigate the world with a sense of control and inner reflection of their own minds in order to find happiness. We cannot remove our instinctive temptations and natural desires or emotions, but we can try our best to avoid the things that will tempt and distract us, whilst cultivating good habits to keep us on the right path.

Once the charioteer, wild horse and noble horse are cooperating, they need not rely on willpower or control alone, the path forward will be natural, pleasurable and easy.

Aristotle’s Four Cardinal Virtues

But reflection, control and good habits don’t always come easy. What qualities does one need in order to harness inner control of their own mind? Perhaps the second most important teaching on happiness came from Plato’s student, Aristotle, whose four cardinal virtues expand on Plato’s teachings of achieving happiness.

With enough practice, one could utilize these character traits without thinking about it, and like the charioteer, can live with ease and happiness.

The first cardinal value is temperance . For Aristotle, temperance is the middle road between excess and deficiency. It is needed to exhibit restraint in one’s actions and stay balanced.

The second cardinal value is fortitude , also known as courage and inner strength in the face of adversity. It is only when one is courageous that they can resist temptations and overcome difficulties.

The third cardinal value is prudence. Those who are happy are able to self-judge and act in a moral way. They can be mindful, learn from their mistakes and strive to be better.

The fourth and last cardinal value is justice , which Aristotle defines as the middle road between being selfless and selfish. Like Plato, Aristotle claimed that while one should pursue their own desires, it is important to help those around them to flourish as well. A happy person will contribute to a better functioning and fairer society.

Aristotle vs Plato on Happiness

Both Plato and Aristotle agreed that humans should strive for happiness since this is the essence of how to live a good life.

More so than Aristotle, Plato was concerned with human virtue and knowing what is good. Knowing the right thing to do will lead one to automatically doing the right thing, and this is why control, understanding and habits are important. In this sense, happiness could be sought and reflected on internally, determined by the individual and their mind state.

Aristotle on the other hand taught that just knowing what was right was not enough – one had to choose to act in a proper manner. For Aristotle, virtue and happiness was a practical and external matter rather than reflective and theoretical. Aristotle held that in order to achieve happiness one must also have experienced fortunate and pleasant circumstances in life.

In this sense, Aristotle took a more scientific approach to grasp the meaning of a good life. This required studying both human character as well as the conditions and circumstances that made a life, as a whole, well-lived.

Another important concept at the heart of Plato’s teachings on virtue and happiness was rooted in his ideas of “ The Good”.

For Plato, The Good is the highest object of the “Intelligible World”, which is made up of essential forms and mathematics. This Intelligible World corresponds to the states of knowledge (episteme) and thinking (dianoia) in man.

Plato taught that the Form (or the idea) of the Good is the origin of all knowledge, but it is not knowledge itself. Humans should pursue the Good but this cannot be done without philosophical reasoning and rationality.

For Plato, true knowledge is not about material objects and desires which we might encounter in daily interactions; it is about the nature of purer and perfect patterns which are models after which all created beings are formed. These are what Plato calls Forms or Ideas.

Plato splits all of existence into two realms: the visible realm and the transcendent realm (intelligible realm) of forms. The visible realm is the physical world that is perceived through senses, and is susceptible to “becoming” and “ceasing to be”. On the other hand, the intelligible realm represents the ultimate reality, is enduring, and is accessible only via reasoning or intellect.

In the Republic, Plato teaches that a life committed to knowledge and virtue will result in happiness and self-fulfilment. To achieve happiness, one should render himself immune to changes in the material world and strive to gain the knowledge of the eternal, immutable forms that reside in the intelligible realm.

How Have Plato’s Ideas on Human Happiness Shaped Modern Day Thinking?

Plato’s teachings on happiness seem more relevant than ever in today’s fast paced world. 2000 years before smartphones, technology, emails and calendar alerts even existed, Plato was already acknowledging the internal battles we all face in a world where we are surrounded by temptation and distractions.

Plato’s teachings are consistent with modern day psychological and scientific theories on habit forming and self control, whereby numerous studies have shown that creating small changes in our daily habits and behaviors can lead to a more productive and happy life.

Want to stop eating unhealthily? Remove unhealthy foods from the house. Want to think more positively? Cultivate good habits by writing in a gratitude journal each day.

When we understand our internal human nature and what pulls us in different directions, we can be aware of what truly makes us happy and what threatens to throw our happiness off course. Understanding and harnessing our inner horses will let us move through life peacefully, efficiently and happily.

How to Achieve Ultimate Happiness? 5 Philosophical Answers

By Claire Johnson BA Philosophy Claire Johnson is a contributing writer in Philosophy and History. She holds a Bachelor's degree in Philosophy from the University of Manchester and has six years of experience in writing about Philosophy and Life Sciences. Claire has traveled across Europe, South East Asia, North America, and Central America to explore different cultures and world views.

Frequently Read Together

Socrates’ Philosophy: The Ancient Greek Philosopher and His Legacy

Aristotle’s Philosophy: Eudaimonia and Virtue Ethics

The Chariot: Plato’s Concept of the Lover’s Soul in Phaedrus

The Philosophy of Happiness in Life (+ Aristotle’s View)

We all hope to be happy and live a ‘good life’– whatever that means! Do you wonder, what does it actually mean?

The basic role of ‘philosophy’ is to ask questions, and think about the nature of human thought and the universe. Thus, a discussion of the philosophy of happiness in life can be seen as an examination of the very nature of happiness and what it means for the universe.

Philosophers have been inquiring about happiness since ancient times. Aristotle, when he asked ‘ what is the ultimate purpose of human existence ’ alluded to the fact that purpose was what he argued to be ‘happiness’. He termed this eudaimonia – “ activity expressing virtue ”. This will all be explained shortly.

The purpose of this article is to explore the philosophy of happiness in life, including taking a closer look at Aristotle’s philosophy and answering some of those “big” questions about happiness and living a ‘good life’. In this article, you will also find some practical tips that hopefully you can put in place in your own life. Enjoy!

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Happiness & Subjective Wellbeing Exercises for free . These detailed, science-based exercises will help you or your clients identify sources of authentic happiness and strategies to boost wellbeing.

This Article Contains:

A look at the philosophy of happiness, aristotle on happiness, what is real happiness, the value and importance of having true happiness in life, the biggest causes that bring true happiness in life, 15 ways to create happy moments in life, five reasons to be happy from a philosophical perspective, finding happiness in family life, a look at happiness and productivity, how does loneliness affect life satisfaction, 6 recommended books, a take-home message.

Happiness. It is a term that is taken for granted in this modern age. However, since the dawn of time, philosophers have been pursuing the inquiry of happiness… after all, the purpose of life is not just to live, but to live ‘well’.

Philosophers ask some key questions about happiness: can people be happy? If so, do they want to? If people have both a desire to be happy and the ability to be happy, does this mean that they should, therefore, pursue happiness for themselves and others? If they can, they want to, and they ought to be happy, but how do they achieve this goal?

To explore the philosophy of happiness in life, first, the history of happiness will be examined.

Democritus, a philosopher from Ancient Greece, was the first philosopher in the western world to examine the nature of happiness (Kesebir & Diener, 2008). He put forth a suggestion that, unlike it was previously thought, happiness does not result from ‘favorable fate’ (i.e. good luck) or other external circumstances (Kesebir & Diener, 2008).

Democritus contended that happiness was a ‘case of mind’, introducing a subjectivist view as to what happiness is (Kesebir & Diener, 2008).

A more objective view of happiness was introduced by Socrates, and his student, Plato.

They put forth the notion that happiness was “ secure enjoyment of what is good and beautiful ” (Plato, 1999, p. 80). Plato developed the idea that the best life is one whereby a person is either pursuing pleasure of exercising intellectual virtues… an argument which, the next key figure in the development of the philosophy of happiness – Aristotle – disagreed with (Waterman, 1993).

The philosophy of Aristotle will be explored in depth in the next section of this article.

Hellenic history (i.e. ancient Greek times) was largely dominated by the prominent theory of hedonism (Kesebir & Diener, 2008).

Hedonism is, to put it simply, the pursuit of pleasure as the only intrinsic good (Waterman, 1993). This was the Cyrenaic view of happiness. It was thought that a good life was denoted by seeking pleasure, and satisfying physical, intellectual/social needs (Kashdan, Biswas-Diener & King, 2008).

Kraut (1979, p. 178) describes hedonic happiness as “ the belief that one is getting the important things one wants, as well as certain pleasant affects that normally go along with this belief ” (Waterman, 1993).

In ancient times, it was also thought that it is not possible to live a good life without living in accordance with reason and morality (Kesebir & Diener, 2008). Epicurus, whose work was dominated by hedonism, contended that in fact, virtue (living according to values) and pleasure are interdependent (Kesebir & Diener, 2008).

In the middle ages, Christian philosophers said that whilst virtue is essential for a good life, that virtue alone is not sufficient for happiness (Kesebir & Diener, 2008).

According to the Christian philosophers, happiness is in the hands of God. Even though the Christians believed that earthly happiness was imperfect, they embraced the idea that Heaven promised eternal happiness (Kesebir & Diener, 2008).

A more secular explanation of happiness was introduced in the Age of Enlightenment.

At this time, in the western world pleasure was regarded as the path to, or even the same thing as, happiness (Kesebir & Diener, 2008). From the early nineteenth century, happiness was seen as a value which is derived from maximum pleasure.

Utilitarians, such as the English philosopher Jeremy Bentham, suggested the following: “ maximum surplus of pleasure over pain as the cardinal goal of human striving ” (Kesebir & Diener, 2008). Utilitarians believe that morals and legislation should be based on whatever will achieve the greatest good for the greatest number of people.

In the modern era, happiness is something we take for granted. It is assumed that humans are entitled to pursue and attain happiness (Kesebir & Diener, 2008). This is evidenced by the fact that in the US declaration of independence, the pursuit of happiness is protected as a fundamental human right! (Conkle, 2008).

Go into any book store and large sections are dedicated to the wide range of ‘self-help’ books all promoting happiness.

What is This Thing Called Happiness?

It is incredibly challenging to define happiness . Modern psychology describes happiness as subjective wellbeing, or “ people’s evaluations of their lives and encompasses both cognitive judgments of satisfaction and affective appraisals of moods and emotions ” (Kesebir & Diener, 2008, p. 118).

The key components of subjective wellbeing are:

- Life satisfaction

- Satisfaction with important aspects of one’s life (for example work, relationships, health)

- The presence of positive affect

- Low levels of negative affect

These four components have featured in philosophical material on happiness since ancient times.

Subjective life satisfaction is a crucial aspect of happiness, which is consistent with the work of contemporary philosopher Wayne Sumner, who described happiness as ‘ a response by a subject to her life conditions as she sees them ’ (1999, p. 156).

Thus, if happiness is ‘a thing’ how is it measured?

Some contemporary philosophers and psychologists question self-report as an appropriate measure of happiness. However, many studies have found that self-report measures of ‘happiness’ (subjective wellbeing) are valid and reliable (Kesebir & Diener, 2008).

Two other accounts of happiness in modern psychology are firstly, the concept of psychological wellbeing (Ryff & Singer, 1996) and secondly, self-determination theory (Ryan & Deci, 2000).

Both of these theories are more consistent with the eudaemonist theories of ‘ flourishing ’ (including Aristotle’s ideas) because they describe the phenomenon of needs (such as autonomy, self-acceptance, and mastery) being met (Kesebir & Diener, 2008).

Eudaimonia will be explained in detail in the next section of the article (keep reading!) but for now, it suffices to say that eudaemonist theories of happiness define ‘happiness’ (eudaimonia) as a state in which an individual strives for the highest human good.

These days, most empirical psychological research puts forward the theory of subjective wellbeing rather than happiness as defined in a eudaimonic sense (Kesebir & Diener, 2008).

Although the terms eudaimonia and subjectivewellbeing are not necessarily interchangeable, Kesebir and Diener (2008) argue that subjective wellbeing can be used to describe wellbeing, even if it may not be an absolutely perfect definition!

Can People be Happy?

In order to adequately address this question, it is necessary to differentiate between ‘ideal’ happiness and ‘actual’ happiness.

‘Ideal’ happiness implies a way of being that is complete, lasting and altogether perfect… probably outside of anyone’s reach! (Kesebir & Diener, 2008). However, despite this, people can actually experience mostly positive emotions and report overall satisfaction with their lives and therefore be deemed ‘happy’.

In fact, most people are happy. In a study conducted by the Pew Research Center in the US (2006), 84% of Americans see themselves as either “very happy” or “pretty happy” (Kesebir & Diener, 2008).

Happiness also has an adaptive function. How is happiness adaptive? Well, positivity and wellbeing are also associated with people being confident enough to explore their environments and approach new goals, which increases the likelihood of them collecting resources.

The fact that most people report being happy, and happiness having an adaptive function, leads Kesebir and Diener (2008) to conclude that yes people can, in fact, be happy.

Do People Want to be Happy?

The overwhelming answer is yes! Research has shown that being happy is desirable. Whilst being happy is certainly not the only goal in life, nonetheless, it is necessary for a good life (Kesebir & Diener, 2008).

A study by King and Napa (1998) showed that Americans view happiness as more relevant to the judgment of what constitutes a good life, rather than either wealth or ‘moral goodness’.

Should People be Happy?

Another way of putting this, is happiness justifiable? Happiness is not just the result of positive outcomes, such as better health, improved work performance, more ethical behavior, and better social relationships (Kesebir & Diener, 2008). It actually precedes and causes these outcomes!

Happiness leads to better health. For example, research undertaken by Danner, Snowdon & Friesen in 2001 examined the content of handwritten autobiographies of Catholic sisters. They found that expression in the writing that was characterized by positive affect predicted longevity 60 years later!

Achievement

Happiness is derived not from pursuing pleasure, but by working towards goals which are reflected in one’s values (Kesebir & Diener, 2008).

Happiness can be predicted not merely by pleasure but by having a sense of meaning , purpose, and fulfillment. Happiness is also associated with better performance in professional life/work.

Social relationships and prosocial behavior

Happiness brings out the best in people… people who are happier are more social, cooperative and ethical (Kesebir & Diener, 2008).

Happy individuals have also been shown to evaluate others more positively, show greater interest in interacting with others socially, and even be more likely to engage in self-disclosure (Kesebir & Diener, 2008).

Happy individuals are also more likely to behave ethically (for example, choosing not to buy something because it is known to be stolen) (Kesebir & Diener, 2008).

How to be happy?

The conditions and sources of happiness will be explored later on, so do keep reading… briefly in the meantime, happiness is caused by wealth, friends and social relationships, religion, and personality. These factors predict happiness.

Download 3 Free Happiness Exercises (PDF)

These detailed, science-based exercises will equip you or your clients with tools to discover authentic happiness and cultivate subjective well-being.

Download 3 Free Happiness Tools Pack (PDF)

By filling out your name and email address below.

- Email Address *

- Your Expertise * Your expertise Therapy Coaching Education Counseling Business Healthcare Other

- Phone This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

Chances are, you have heard of the ancient Greek philosopher Aristotle. Are you aware that it was Aristotle who introduced the ‘science of happiness’? (Pursuit of Happiness, 2018).

Founder of Lyceum, the first scientific institute in Athens, Aristotle delivered a series of lectures termed Nicomachean Ethics to present his theory of happiness (Pursuit of Happiness, 2018).

Aristotle asked, “ what is the ultimate purpose of human existence? ”. He thought that a worthwhile goal should be to pursue “ that which is always desirable in itself and never for the sake of something else ” (Pursuit of Happiness, 2018).

However, Aristotle disagreed with the Cyrenaic view that the only intrinsic good is pleasure (Waterman, 1993).

In developing his theory of ‘happiness’, Aristotle drew upon his knowledge about nature. He contended that what separates man from animal is rational capacity – arguing that a human’s unique function is to reason. He went on to say that pleasure alone cannot result in happiness because animals are driven by the pursuit of pleasure and according to Aristotle man has greater capacities than animals (Pursuit of Happiness, 2018).

Instead, he put forward the term ‘ eudaimonia ’.

To explain simply, eudaimonia is defined as ‘ activity expressing virtue ’ or what Aristotle conceived as happiness. Aristotle’s theory of happiness was as follows:

‘the function of man is to live a certain kind of life, and this activity implies a rational principle, and the function of a good man is the good and noble performance of these, and if any action is well performed it is performed in accord with the appropriate excellence: if this is the case, then happiness turns out to be an activity of the soul in accordance with virtue’

(Aristotle, 2004).

A key component of Aristotle’s theory of happiness is the factor of virtue. He contended that in aiming for happiness, the most important factor is to have ‘complete virtue’ or – in other words – good moral character (Pursuit of Happiness, 2008).

Aristotle identified friendship as being one of the most important virtues in achieving the goal of eudaimonia (Pursuit of Happiness, 2008). In fact, he valued friendship very highly, and described a ‘virtuous’ friendship as the most enjoyable, combining both pleasure and virtue.

Aristotle went on to put forward his belief that happiness involves, through the course of an entire life, choosing the ‘greater good’ not necessarily that which brings immediate, short term pleasure (Pursuit of Happiness, 2008).

Thus, according to Aristotle, happiness can only be achieved at the life-end: it is a goal, not a temporary state of being (Pursuit of Happiness, 2008). Aristotle believed that happiness is not short-lived:

‘for as it is not one swallow or one fine day that makes a spring, so it is not one day or a short time that makes a man blessed and happy’

Happiness (eudaimonia), to Aristotle, meant attaining the ‘daimon’ or perfect self (Waterman, 1990). Reaching the ‘ultimate perfection of our natures’, as Aristotle meant by happiness, includes rational reflection (Pursuit of Happiness, 2008).

He argued that education was the embodiment of character refinement (Pursuit of Happiness, 2008). Striving for the daimon (perfect self) gives life meaning and direction (Waterman, 1990). Having a meaningful, purposeful life is valuable.

Efforts that the individual puts in to strive for the daimon are termed ‘ personally expressive ’ (Waterman, 1990).

Personal expressiveness involves intense involvement in an activity, a sense of fulfillment when engaged in an activity, and having a sense of acting in accordance with one’s purpose (Waterman, 1990). It refers to putting in effort, feeling challenged and competent, having clear goals and concentrating (Waterman, 1993).

According to Aristotle, eudaimonia and hedonic enjoyment are separate and distinguishable (Waterman, 1993). However, in a study of university students, personal expressiveness (which is, after all a component of eudaimonia) was found to be positively correlated with hedonic enjoyment (Waterman, 1993).

Telfer (1980), on the other hand, claimed that eudaimonia is a sufficient but not a necessary condition for achieving hedonic enjoyment (Waterman, 1993). How are eudaimonia and hedonic enjoyment different?

Well, personal expressiveness (from striving for eudaimonia) is associated with successfully achieving self-realization, while hedonic enjoyment does not (Waterman, 1993).

Thus, Aristotle identified the best possible life goal and the achievement of the highest level of meeting one’s needs, self-realization many, many years before Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs!

Results from Waterman’s 1993 study provide empirical support for the association between ‘personal expressiveness’ and what was described by Csikszentimikalyi (1975) as “flow” (Waterman, 1993).

Flow , conceptualized as a cognitive-affective state, is an experience whereby the challenge a task presents to a person is aligned with the skills that individual has to deal with such challenges.

Understanding that flow is a distinctive cognitive-affective state combines hedonic enjoyment and personal expressiveness (Waterman, 1993).

Aristotle’s work Nicomachean Ethics contributed a great deal to the understanding of what happiness is. To summarise from Pursuit of Happiness (2018), according to Aristotle, the purpose and ultimate goal in life is to achieve eudaimonia (‘happiness’). He believed that eudaimonia was not simply virtue, nor pleasure, but rather it was the exercise of virtue.

According to Aristotle, eudaimonia is a lifelong goal and depends on rational reflection. To achieve a balance between excess and deficiency (‘temperance’) one displays virtues – for example, generosity, justice, friendship, and citizenship. Eudaimonia requires intellectual contemplation, in order to meet our rational capacities.

To answer Aristotle’s question of “ what is the ultimate purpose of human existence ” is not a simple task, but perhaps the best answer is that the ultimate goal for human beings is to strive for ‘eudaimonia’ (happiness).

Aristotle & virtue theory – CrashCourse

What does ‘true’ happiness look like? Is it landing the dream job? Having a child ? Graduating from university? Whilst happiness is certainly associated with these ‘external’ factors, true happiness is quite different.

To be truly happy, a person’s sense of contentment with their life needs to come from within (Puff, 2018). In other words, real happiness is internal.

There are a few features that characterize ‘true’ (or real) happiness. The first is acceptance . A truly happy individual accepts reality for what it is, and what’s more, they actually come to love ‘what is’ (Puff, 2018).

This acceptance allows a person to feel content. As well as accepting the true state of affairs, real happiness involves accepting the fact that change is inevitable (Puff, 2018). Being willing to accept change as part of life means that truly happy people are in a position to be adaptive.

A state of real happiness is also reflected by a person having an understanding of the transience of life (Puff, 2018). This is important because understanding that in life, both good and ‘bad’ are only short-lived means that truly happy individuals have an understanding that ‘this too shall pass’.

Finally, another aspect of real happiness is an appreciation of the people in an individual’s life. (Puff, 2018). Strong relationships characterize people who are truly ‘flourishing’.

Most people would say that, if they could, they would like to be happy. As well as being desirable, happiness is both important and valuable.

Happy people have better social and work relationships (Conkle, 2008).

In terms of career, happy individuals are more likely to complete college, secure employment, receive positive work evaluations from their superiors, earn higher incomes, and are less likely to lose their job – and, in case of being laid off, people who are happy are re-employed more quickly (Kesebir & Diener, 2008).

Positive emotions also precede and promote career success (Lyubomirsky, 2018). Happy workers are less likely to burn out, be absent from work and quit their job (Lyubomirsky, 2018). Further on in this article, the relationship between happiness and productivity will be explored more thoroughly.

It has also been found that people who are happy contribute more to society (Conkle, 2008). There is also an association between happiness and cooperation – those who are happy are more cooperative (Kesebir & Diener, 2008). They are also more likely to display ethical behavior (Kesebir & Diener, 2008).

Perhaps the most important reason to have true happiness in life is that it is linked to longevity. True happiness is a significant predictor of a longer, healthier life (Conkle, 2008).

It is not only the effects of happiness that benefit individuals. Whole countries can flourish too – according to research, nations that are rated as happier also score more highly on generalized trust, volunteerism and democratic attitudes (Kesebir & Diener, 2008).

However, as well as these objective reasons why happiness is important, happiness also brings with it some positive experiences and feelings. For example, true happiness is related to feelings of meaning and purpose (Kesebir & Diener, 2008).

It is also associated with a sense of fulfillment, plus a feeling of achievement that is attained through actively striving for, and making progress towards, valuable goals (Kesebir & Diener, 2008).

Interestingly, objective life circumstances (demographic details) only account for 8% – 15% of the variance in happiness (Kesebir & Diener, 2008). So what causes true happiness? Kesebir and Diener (2008) identified five sources of happiness:

Wealth is the first cause of happiness. Studies have shown a significant positive correlation between wealth and happiness. It is the case that having enough (i.e. adequate) money is necessary for happiness but is not sufficient to cause happiness. Money gives people freedom, and having enough money enables individuals to meet their needs – e.g. housing, food, and health-care.

Satisfaction with income has been shown to be related to happiness (Diener, 1984). However, money is not the guarantee of happiness – consider lottery winners. Whilst it is necessary to have sufficient money this alone will not cause happiness. So, what else is a source of happiness?

Having friends and social relationships has been shown to be a leading cause of happiness. Humans are primarily social beings and have a need for social connection.

A sense of community is associated with life satisfaction (Diener, 1984). Making and keeping friends is positively correlated with wellbeing. Aristotle (2000) stated that “no one would choose to live without friends, even if he had all the other goods” (p. 143).

In fact, the association between friendship/social support and happiness has been supported by empirical research. Furthermore, being satisfied with family life and marriage is the key to subjective wellbeing (Diener, 1984).

Another source of happiness is religion . While not true universally, religion has been associated with greater happiness. Positive effects have been found with taking part in religious services.

Having a strong religious affiliation has also been shown to be of benefit. Engaging in prayer, and having a relationship with God is also related to greater happiness.

Finally, a large determinant of happiness is personality . Research supports the fact that individual differences in how a person responds both to events and also to other people have an impact on the levels of a person’s happiness.

Lykken & Tellegen (1996) found that stable temperamental tendencies (those that are inherited genetically) contribute up to 50% in the total variability in happiness. This research found that many personality factors – extraversion, neuroticism – as well as self-esteem , optimism , trust , agreeableness, repressive defensiveness, a desire for control, and hardiness all play a part in how happy a person is.

We can, to a certain extent, determine how happy we feel. Kane (2017) has come up with 15 ways in which happiness can be increased:

1. Find joy in the little things

Savoring ordinary moments in everyday life is a skill that can be learned (Tartarkovsky, 2016). For most of us, we spend so much time thinking about things we’re not currently even doing! This can make us unhappy.

Happiness can, in fact, be predicted by where our minds wander to when we’re not focused on the present. By appreciating the simple things in life, we foster positive emotions…from admiring a beautiful flower to enjoying a cup of tea, finding joy in the little things is associated with increased happiness.

2. Start each day with a smile

It sounds easy, but smiling is associated with feeling happy. Beginning the day on a positive note can vastly improve wellbeing.

3. Connect with others

As mentioned in the previous section, having friendship and social support is definitely a source of happiness. So, to create more happy moments in life, step away from the desk and initiate a conversation with a work colleague, or send an SMS to someone you have not seen for a while. Take opportunities to interact with other people as they arise.

4. Do what you’re most passionate about

Using your strengths and finding an activity to engage in which leads to ‘flow’ has been identified as an enduring pathway to happiness. Being completely engaged in an activity is termed ‘flow’. What constitutes an experience of flow?

To begin with, the task needs to require skill but not be too challenging (Tartarkovsky, 2016). It should have clear goals and allow you to completely immerse yourself in what you’re doing so your mind doesn’t wander (Tartarkovsky, 2016). It should completely absorb your attention and give a sense of being ‘in the zone’ (Tartarkovsky, 2016). Perhaps the easiest way to identify a flow experience is that you lose track of time.

By doing what you’re most passionate about, you are more likely to use your strengths and find a sense of flow .

5. Count your blessings and be thankful

Gratitude is known to increase happiness. Gratitude has been defined as having an appreciation for what you have, and being able to reflect on that (Tartarkovsky, 2016). Gratitude creates positive emotions, enhances relationships and is associated with better health (Tartarkovsky, 2016).

Examples of ways to engage in gratitude include writing a gratitude journal, or express appreciation – such as, send a ‘thank you’ card to someone.

6. Choose to be positive and see the best in every situation

Taking a ‘glass half full’ attitude to life can certainly enhance feelings of happiness. Finding the positives in even difficult situations helps to foster positive affect. As one psychologist from Harvard Medical School, Siegel, said “relatively small changes in our attitudes can yield relatively big changes in our sense of wellbeing” (Tartarkovsky, 2016).

7. Take steps to enrich your life

A great way to develop a happier life is to learn something new. By being mentally active and developing new skills, this can promote happiness. For example, learn a musical instrument, or a foreign language, the sky’s the limit!

8. Create goals and plans to achieve what you want most

Striving for things we really want can make us feel happy, provided the goals are realistic. Having goals gives life purpose and direction, and a sense of achievement.

9. Live in the moment

Though easier said than done, a helpful way to create happy moments in life is to live for the moment – not to ruminate about the past, or to focus on the future. Staying in the ‘here and now’ can help us feel happier.

10. Be good to yourself

Treat yourself as well as you would treat a person whom you love and care about. Showing self-compassion can lead to happy moments and improve overall wellbeing.

11. Ask for help when you need it

Seeking help may not immediately come to mind when considering how to create happy moments. However, reaching out for support is one way to achieve happiness. As the old adage says “a problem shared is a problem halved”.

Having someone help you is not a sign of weakness. Rather, by asking for help, you are reducing the burden of a problem on yourself.

12. Let go of sadness and disappointment

Negative emotions can compromise one’s sense of happiness, especially if a person ruminates about what ‘could have been’. Whilst everyone feels such emotions at times, holding onto feelings of sadness and disappointment can really weigh a person down and prevent them from feeling happy and content.

13. Practice mindfulness

The positive effects of practicing mindfulness are widespread and numerous, including increasing levels of happiness. There is lots of material on this blog about mindfulness and its’ positive effects. Mindfulness is a skill and, like any skill, it can be learned. Learning to be mindful can help a person become happier.

14. Walk in nature

Exercise is known to release endorphins, and as such engaging in physical activity is one way to lift mood and create happy moments. Even more beneficial than simply walking is to walk in nature, which has been shown to increase happiness.

15. Laugh, and make time to play

Laughter really is the best medicine! Having a laugh is associated with feeling better. Also, it is beneficial for the sense of wellbeing not to take life too seriously. Just as children find joy in simple pleasures, they also love to play. Engaging in ‘play’ – activities done purely for fun – is associated with increased happiness.

Philosophers believe that happiness is not by itself sufficient to achieve a state of wellbeing, but at the same time, they agree that it is one of the primary factors found in individuals who lead a ‘good life’ (Haybron, 2011).

What then, are reasons to be happy from a philosophical perspective… what contributes to a person living a ‘good life’? This can also be understood as a person having ‘psychosocial prosperity’ (Haybron, 2011).

- One reason why a person can feel a sense of happiness is if they have been treated with respect in the last day (Haybron, 2011). How we are treated by others contributes to our overall wellbeing. Being treated with respect helps us develop a sense of self-worth.

- Another reason to feel happy is if one has family and friends they can rely on and count on in times of need (Haybron, 2011). Having a strong social network is an important component of happiness.

- Perhaps a person has learned something new. They may take this for granted, however, learning something new actually contributes to our psychosocial prosperity (Haybron, 2011).

- From a philosophical perspective, a reason to be happy is a person having the opportunity to do what they do best (Haybron, 2011). Using strengths for the greater good is one key to a more meaningful life (Tartarkovsky, 2016). As an example, a musician can derive happiness by creating music and a sports-person can feel happy by training or participating in competitions. Meeting our potential also contributes to wellbeing.

- A final reason to be happy from a philosophical perspective is a person having the liberty to choose how they spend their time (Haybron, 2011). This is a freedom to be celebrated. Being autonomous can contribute to a person living their best life.

Many of us spend a lot of time with our families. However, as much we love our partners, children, siblings, and extended families, at times family relationships can be fraught with challenges and problems. Nonetheless, it is possible for us to find happiness in family life by doing some simple, yet effective things suggested by Mann (2007):

- Enjoy your family’s company

- Exchange stories – for example, about what your day was like in the evening

- Make your marriage, or relationship, the priority

- Take time to eat meals together as a family

- Enjoy simply having fun with one another

- Make sure that your family and its needs come before your friends

- Limit number of extra-curricular activities

- Develop family traditions and honor rituals

- Aim to make your home a calm place to spend time

- Don’t argue in front of children

- Don’t work excessively

- Encourage siblings to get along with one another

- Have family ‘in-jokes’

- Be adaptable

- Communicate, including active listening

Take time to appreciate your family, and focus on the little things you can do to find happiness in family life.

The aim of any workplace is to have productive employees. This leads to the question – can happiness increase productivity? The results are unequivocal!

Researchers Boehm and Lyubomirsky define a ‘happy worker’ as one who frequently experiences positive emotions such as joy, satisfaction, contentment, enthusiasm, and interest (Oswald, Proto & Sgroi, 2009).

They conducted longitudinal as well as experimental studies, and their research clearly showed that people who could be classified as ‘happy’ were more likely to succeed in their careers. Amabile et al. (2005) also found that happiness results in greater creativity.

Why are happy workers more productive?

It has been suggested that the link between positive mood and work appears to be mediated by intrinsic motivation (that is, performing a task due to internal inspiration rather than external reasons) (Oswald et al., 2009). This makes sense because if one is feeling more joyful, the person is more likely to find their work meaningful and intrinsically rewarding.

It has been found by some experimental studies that happiness raises productivity. For example, research has shown that the experience of positive affect means that individuals change their allocation of time to completing more interesting tasks, but still manage to maintain their performance for the less interesting tasks (Oswald et al., 2009).

Other research has reported that positive affect influences memory recall and the likelihood of altruistic actions. However, much of this research has taken place in laboratory sessions where participation was unpaid. Which certainly leads to the obvious question… does happiness actually increase productivity in a true employment situation?

Oswald and colleagues (2009) did some research with very clear results on the relationship between happiness and productivity. They conducted two separate experiments.

The first experiment included 182 participants from the University of Warwick. The study involved some participants watching a short video clip designed to try and increase levels of happiness, and then completing a task which they were paid for in terms of both questions answered and accuracy. The participants who watched the video showed significantly greater productivity.

Most interestingly, however, 16 individuals did not display increased happiness after watching the movie clip, and these people did not show the same increase in productivity! Thus, this experiment certainly supported the notion that an increase in productivity can be linked to happiness.

Oswald and colleagues also conducted a second study which involved a further 179 participants who had not taken part in the first experiment. These individuals reported their level of happiness and were subsequently asked whether they had experienced a ‘bad life event’ (which was defined as bereavement or illness in the family) in the last two years.

A statistically significant effect was found… experiencing a bad life event, which was classified by the experts as ‘happiness shocks’ was related to lower levels of performance on the task.

Examining the evidence certainly makes one thing clear: happiness is certainly related to productivity both in unpaid and paid tasks. This has tremendous implications for the work-force and provides an impetus for working towards happier employees.

According to the Belonging Hypothesis put forth by psychologists Baumeister and Leary in 1995, human beings have an almost universal, fundamental human need to have a certain degree of interaction with others and to form relationships.

Indeed, people who are lonely have an unmet need to belong (Mellor, Stokes, Firth, Hayashi & Cummins, 2008). Loneliness has been found in a plethora of research to have a very negative effect on psychological wellbeing, and also health (Kim, 1997).

What about ‘happiness’? In other words, can loneliness also have an impact on life satisfaction?

There is evidence to suggest that loneliness does affect life satisfaction. Gray, Ventis, and Hayslip (1992) conducted a study of 60 elderly people living in the community. Their findings were clear: the aged person’s sense of isolation, and loneliness , explained the variation in life satisfaction (Gray et al., 1992).

Clearly, lonely older persons were less satisfied with their lives overall. In other research, Mellor and colleagues (2008) found that individuals who were less lonely had higher ratings of life satisfaction.

It may be assumed that only older people are prone to feeling isolated and lonely, however, an interesting study by Neto (1995) looked at satisfaction with life among second-generation migrants.

The researchers studied 519 Portuguese youth who was actually born in France. The study found that loneliness had a clear negative correlation with the satisfaction with life expressed by the young people (Neto, 1995). Indeed, along with the perceived state of health, loneliness was the strongest predictor of satisfaction with life (Neto, 1995).

Therefore, yes, loneliness affects life satisfaction. Loneliness is associated with feeling less satisfied with one’s life, and, presumably, less happy overall.

17 Exercises To Increase Happiness and Wellbeing

Add these 17 Happiness & Subjective Well-Being Exercises [PDF] to your toolkit and help others experience greater purpose, meaning, and positive emotions.

Created by Experts. 100% Science-based.

Perhaps you have a desire to understand this topic further… great! Here are some books that you can read to further your understanding:

- Exploring Happiness: From Aristotle to brain science – S. Bok (2010) ( Amazon )

- Nicomachean ethics – Aristotle (2000). R Crisp, ed. ( Amazon )

- What is this thing called happiness? – F. Feldman (2010) ( Amazon )

- Authentic happiness: Using the new Positive Psychology to realize your potential for lasting fulfillment – M. Seligman (2004) ( Amazon )

- Philosophy of happiness: A theoretical and practical examination – M. Janello (2014) ( Amazon )

- Happiness: A Philosopher’s guide – F. Lenoir (2015) ( Amazon )

I don’t know about you but, whilst exploring the philosophy of happiness is fascinating, it can be incredibly overwhelming too. I hope that I have managed to simplify some of the ideas about happiness so that you have a better understanding of the nature of happiness and what it means to live a ‘good life’.

Philosophy can be complex, but if you can take one message from this article it is that it is important and worthwhile for humans to strive for wellbeing and ‘true happiness’. Whilst Aristotle argued that ‘eudaimonia’ (happiness) cannot be achieved until the end of one’s life, tips in this article show that each of us has the capacity to create happy moments each and every day.

What can you do today to embrace the ‘good life’? What ideas do you have about happiness – what does real happiness look like for you? What are your opinions as to what the philosophy of happiness in life means?

This article can provide a helpful resource for understanding more about the nature of happiness, so feel free to look back at it down the track. I would love to hear your thoughts on this fascinating topic!

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Happiness Exercises for free .

- Amabile, T. M., Basade, S. G., Mueller, J. S., & Staw, B. M. (2005). Affect and creativity at work. Administrative Science Quarterly, 50 , 367-403.

- Aristotle (2000). Nicomachean Ethics . R. Crisp (ed.). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

- Aristotle (2004). Nicomachean Ethics . Hugh Treddenick (ed.). London: Penguin.

- Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117 , 498 – 529.

- Conkle, A. (2008). Serious research on happiness. Association for Psychological Science . Retrieved from https://www.psychologicalscience.org/observe/serious-research-on-happiness

- Danner, D., Snowdon, D., & Friesen, W. (2001). Positive emotions in early life and longevity: Findings from the nun study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80 , 804 – 813.

- Diener, E. (1984). Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 95 , 542 – 575

- Gray, G. R., Ventis, D. G., & Hayslip, B. (1992). Socio-cognitive skills as a determinant of life satisfaction in aged persons. The International Journal of Aging & Human Development , 35, 205 – 218.

- Haybron, D. (2011). Happiness. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved from https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/happiness

- Kane, S. (2017). 15 ways to increase your happiness. Psych Central. Retrieved from https://psychcentral.com/lib/15-ways-to-increase-your-happiness

- Kashdan, T. B., Biswas-Diener, R., & King, L. A. (2008). Reconsidering happiness: the costs of distinguishing between hedonics and eudaimonia. Journal of Positive Psychology, 3 , 219 – 233.

- Kesebir, P., & Diener, E. (2008). In pursuit of happiness: empirical answers to philosophical questions. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3 , 117-125.

- Kim, O. S. (1997). Korean version of the revised UCLA loneliness scale: reliability and validity test. Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing,? , 871 – 879.

- King, L. A., & Napa, C. K. (1998). What makes a life good? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75 , 156 – 165.

- Lykken, D., & Tellegan, A. (1996). Happiness is a stochastic phenomenon. Psychological Science, 7 , 186-189.

- Lyubomirsky, S. (2018). Is happiness a consequence or cause of career success? Psychology Today . Retrieved from https://www.psychologytoday.com/intl/blog/how-happiness/201808/is-happiness-consequence-or-cause-career-success

- Mann, D. (2007). 15 secrets of happy families. Web MD. Retrieved from https://www.webmd.com/parenting/features/15-secrets-to-have-a-happy-family

- Mellor, D., Stokes, M., Firth, L., Hayashi, Y. & Cummins, R. (2008). Need for belonging, relationship satisfaction, loneliness and life satisfaction. Personality and Individual Differences, 45 , 213 – 218.

- Neto, F. (1995). Predictors of satisfaction with life among second generation migrants. Social Indicators Research, 35 , 93-116.

- Oswald, A. J., Proto, E., & Sgroi, D. (2009). Happiness and productivity, IZA Discussion Papers, No. 4645, Institute for the Study of Labor (IZA), Bonn. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/10419/35451

- Plato (1999). The Symposium . Walter Hamilton (ed). London: Penguin Classics

- Puff, R. (2018). The pitfalls to pursuing happiness. Psychology Today. Retrieved from https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/meditation-modern-life/201809/the-pitfalls-pursuing-happiness

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development and wellbeing. American Psychologist, 55 , 68 – 78.

- Ryff, C. D., & Singer, B. (1996). Psychological wellbeing: meaning, measurement, and implications for psychotherapy research. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 65 , 14 – 23.

- Tartarkovsky, M. (2016). Five pathways to happiness. Psych Central. Retrieved from https://psychcentral.com/lib/five-pathways-to-happiness

- The Pursuit of Happiness (2018). Aristotle. Retrieved from https://www.pursuit-of-happiness.org/history-of-happiness/aristotle

- Waterman, A. S. (1990). The relevance of Aristotle’s conception of eudaimonia for the psychological study of happiness. Theoretical and Philosophical Psychology, 10 , 39 – 44

- Waterman, A. S. (1993). Two conceptions of happiness: Contrasts of personal expressiveness (eudaimonia) and hedonic enjoyment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 64 , 678 – 691.

Share this article:

Article feedback

What our readers think.

Thank you for sharing this amazing and wonderful article of yours. It enlightened me. Can’t wait to read more.

really thought this statement was insightful: Well, positivity and wellbeing are also associated with people being confident enough to explore their environments and approach new goals, which increases the likelihood of them collecting resources.

Late but still find it very useful. Happiness is what defines humans’ activeness. Thanks for the good explore

Reading this make me more happy. Thanks Author.

This is wonderful article. Thank you for writing this . May God bless you all time.

Let us know your thoughts Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Related articles

Embracing JOMO: Finding Joy in Missing Out

We’ve probably all heard of FOMO, or ‘the fear of missing out’. FOMO is the currency of social media platforms, eager to encourage us to [...]

The True Meaning of Hedonism: A Philosophical Perspective

“If it feels good, do it, you only live once”. Hedonists are always up for a good time and believe the pursuit of pleasure and [...]

Happiness Economics: Can Money Buy Happiness?

Do you ever daydream about winning the lottery? After all, it only costs a small amount, a slight risk, with the possibility of a substantial [...]

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (49)

- Coaching & Application (58)

- Compassion (25)

- Counseling (51)

- Emotional Intelligence (23)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (21)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (20)

- Mindfulness (44)

- Motivation & Goals (45)

- Optimism & Mindset (34)

- Positive CBT (30)

- Positive Communication (21)

- Positive Education (47)

- Positive Emotions (32)

- Positive Leadership (19)

- Positive Parenting (15)

- Positive Psychology (34)

- Positive Workplace (37)

- Productivity (17)

- Relationships (43)

- Resilience & Coping (38)

- Self Awareness (21)

- Self Esteem (38)

- Strengths & Virtues (32)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (34)

- Theory & Books (46)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (64)

3 Happiness Exercises Pack [PDF]

- Table of Contents

- New in this Archive

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

There are roughly two philosophical literatures on “happiness,” each corresponding to a different sense of the term. One uses ‘happiness’ as a value term, roughly synonymous with well-being or flourishing. The other body of work uses the word as a purely descriptive psychological term, akin to ‘depression’ or ‘tranquility’. An important project in the philosophy of happiness is simply getting clear on what various writers are talking about: what are the important meanings of the term and how do they connect? While the “well-being” sense of happiness receives significant attention in the contemporary literature on well-being, the psychological notion is undergoing a revival as a major focus of philosophical inquiry, following on recent developments in the science of happiness. This entry focuses on the psychological sense of happiness (for the well-being notion, see the entry on well-being ). The main accounts of happiness in this sense are hedonism, the life satisfaction theory, and the emotional state theory. Leaving verbal questions behind, we find that happiness in the psychological sense has always been an important concern of philosophers. Yet the significance of happiness for a good life has been hotly disputed in recent decades. Further questions of contemporary interest concern the relation between the philosophy and science of happiness, as well as the role of happiness in social and political decision-making.

1.1 Two senses of ‘happiness’

1.2 clarifying our inquiry, 2.1 the chief candidates, 2.2 methodology: settling on a theory, 2.3 life satisfaction versus affect-based accounts, 2.4 hedonism versus emotional state, 2.5 hybrid accounts, 3.1 can happiness be measured, 3.2 empirical findings: overview, 3.3 the sources of happiness, 4.1 doubts about the value of happiness, 4.2 restoring happiness to the theory of well-being, 4.3 is happiness overrated, 5.1 normative issues, 5.2 mistakes in the pursuit of happiness, 5.3 the politics of happiness, other internet resources, related entries, 1. the meanings of ‘happiness’.

What is happiness? This question has no straightforward answer, because the meaning of the question itself is unclear. What exactly is being asked? Perhaps you want to know what the word ‘happiness’ means. In that case your inquiry is linguistic. Chances are you had something more interesting in mind: perhaps you want to know about the thing , happiness, itself. Is it pleasure, a life of prosperity, something else? Yet we can't answer that question until we have some notion of what we mean by the word.

Philosophers who write about “happiness” typically take their subject matter to be either of two things, each corresponding to a different sense of the term:

- A state of mind

- A life that goes well for the person leading it

In the first case our concern is simply a psychological matter. Just as inquiry about pleasure or depression fundamentally concerns questions of psychology, inquiry about happiness in this sense—call it the (long-term) “psychological sense”—is fundamentally the study of certain mental states. What is this state of mind we call happiness? Typical answers to this question include life satisfaction, pleasure, or a positive emotional condition.

Having answered that question, a further question arises: how valuable is this mental state? Since ‘happiness’ in this sense is just a psychological term, you could intelligibly say that happiness isn't valuable at all. Perhaps you are a high-achieving intellectual who thinks that only ignoramuses can be happy. On this sort of view, happy people are to be pitied, not envied. The present article will center on happiness in the psychological sense.

In the second case, our subject matter is a kind of value , namely what philosophers nowadays tend to call prudential value —or, more commonly, well-being , welfare , utility or flourishing . (For further discussion, see the entry on well-being . Whether these terms are really equivalent remains a matter of dispute, but this article will usually treat them as interchangeable.) “Happiness” in this sense concerns what benefits a person, is good for her, makes her better off, serves her interests, or is desirable for her for her sake. To be high in well-being is to be faring well, doing well, fortunate, or in an enviable condition. Ill-being, or doing badly, may call for sympathy or pity, whereas we envy or rejoice in the good fortune of others, and feel gratitude for our own. Being good for someone differs from simply being good, period: perhaps it is always good, period, for you to be honest; yet it may not always be good for you , as when it entails self-sacrifice. Not coincidentally, the word ‘happiness’ derives from the term for good fortune, or “good hap,” and indeed the terms used to translate it in other languages have similar roots. In this sense of the term—call it the “well-being sense”—happiness refers to a life of well-being or flourishing: a life that goes well for you.