- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2024 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

Kohlberg's Theory of Moral Development

Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/IMG_9791-89504ab694d54b66bbd72cb84ffb860e.jpg)

Verywell / Bailey Mariner

- Applications

- Other Theories

Take This Pop Quiz

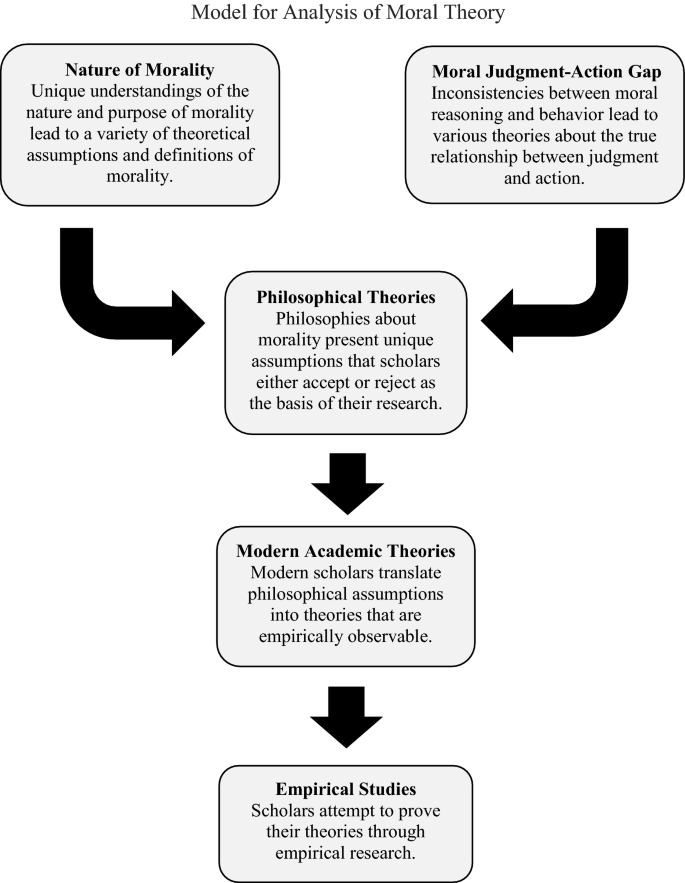

Kohlberg's theory of moral development is a theory that focuses on how children develop morality and moral reasoning. Kohlberg's theory suggests that moral development occurs in a series of six stages and that moral logic is primarily focused on seeking and maintaining justice.

Here we discuss how Kohlberg developed his theory of moral development and the six stages he identified as part of this process. We also share some critiques of Kohlberg's theory, many of which suggest that it may be biased based on the limited demographics of the subjects studied.

Test Your Knowledge

At the end of this article, take a fast and free pop quiz to see how much you've learned about Kohlberg's theory.

What Is Moral Development?

Moral development is the process by which people develop the distinction between right and wrong (morality) and engage in reasoning between the two (moral reasoning).

How do people develop morality? This question has fascinated parents, religious leaders, and philosophers for ages, but moral development has also become a hot-button issue in psychology and education. Do parental or societal influences play a greater role in moral development? Do all kids develop morality in similar ways?

American psychologist Lawrence Kohlberg developed one of the best-known theories exploring some of these basic questions. His work modified and expanded upon Jean Piaget's previous work but was more centered on explaining how children develop moral reasoning.

Kohlberg extended Piaget's theory, proposing that moral development is a continual process that occurs throughout the lifespan. Kohlberg's theory outlines six stages of moral development within three different levels.

In recent years, Kohlberg's theory has been criticized as being Western-centric with a bias toward men (he primarily used male research subjects) and for having a narrow worldview based on upper-middle-class value systems and perspectives.

How Kohlberg Developed His Theory

Kohlberg based his theory on a series of moral dilemmas presented to his study subjects. Participants were also interviewed to determine the reasoning behind their judgments in each scenario.

One example was "Heinz Steals the Drug." In this scenario, a woman has cancer and her doctors believe only one drug might save her. This drug had been discovered by a local pharmacist and he was able to make it for $200 per dose and sell it for $2,000 per dose. The woman's husband, Heinz, could only raise $1,000 to buy the drug.

He tried to negotiate with the pharmacist for a lower price or to be extended credit to pay for it over time. But the pharmacist refused to sell it for any less or to accept partial payments. Rebuffed, Heinz instead broke into the pharmacy and stole the drug to save his wife. Kohlberg asked, "Should the husband have done that?"

Kohlberg was not interested so much in the answer to whether Heinz was wrong or right but in the reasoning for each participant's decision. He then classified their reasoning into the stages of his theory of moral development.

Stages of Moral Development

Kohlberg's theory is broken down into three primary levels. At each level of moral development, there are two stages. Similar to how Piaget believed that not all people reach the highest levels of cognitive development, Kohlberg believed not everyone progresses to the highest stages of moral development.

Level 1. Preconventional Morality

Preconventional morality is the earliest period of moral development. It lasts until around the age of 9. At this age, children's decisions are primarily shaped by the expectations of adults and the consequences of breaking the rules. There are two stages within this level:

- Stage 1 (Obedience and Punishment) : The earliest stages of moral development, obedience and punishment are especially common in young children, but adults are also capable of expressing this type of reasoning. According to Kohlberg, people at this stage see rules as fixed and absolute. Obeying the rules is important because it is a way to avoid punishment.

- Stage 2 (Individualism and Exchange) : At the individualism and exchange stage of moral development, children account for individual points of view and judge actions based on how they serve individual needs. In the Heinz dilemma, children argued that the best course of action was the choice that best served Heinz’s needs. Reciprocity is possible at this point in moral development, but only if it serves one's own interests.

Level 2. Conventional Morality

The next period of moral development is marked by the acceptance of social rules regarding what is good and moral. During this time, adolescents and adults internalize the moral standards they have learned from their role models and from society.

This period also focuses on the acceptance of authority and conforming to the norms of the group. There are two stages at this level of morality:

- Stage 3 (Developing Good Interpersonal Relationships) : Often referred to as the "good boy-good girl" orientation, this stage of the interpersonal relationship of moral development is focused on living up to social expectations and roles . There is an emphasis on conformity , being "nice," and consideration of how choices influence relationships.

- Stage 4 (Maintaining Social Order) : This stage is focused on ensuring that social order is maintained. At this stage of moral development, people begin to consider society as a whole when making judgments. The focus is on maintaining law and order by following the rules, doing one’s duty, and respecting authority.

Level 3. Postconventional Morality

At this level of moral development, people develop an understanding of abstract principles of morality. The two stages at this level are:

- Stage 5 (Social Contract and Individual Rights ): The ideas of a social contract and individual rights cause people in the next stage to begin to account for the differing values, opinions, and beliefs of other people. Rules of law are important for maintaining a society, but members of the society should agree upon these standards.

- Stage 6 (Universal Principles) : Kohlberg’s final level of moral reasoning is based on universal ethical principles and abstract reasoning. At this stage, people follow these internalized principles of justice, even if they conflict with laws and rules.

Kohlberg believed that only a relatively small percentage of people ever reach the post-conventional stages (around 10 to 15%). One analysis found that while stages one to four could be seen as universal in populations throughout the world, the fifth and sixth stages were extremely rare in all populations.

Applications for Kohlberg's Theory

Understanding Kohlberg's theory of moral development is important in that it can help parents guide their children as they develop their moral character. Parents with younger children might work on rule obeyance, for instance, whereas they might teach older children about social expectations.

Teachers and other educators can also apply Kohlberg's theory in the classroom, providing additional moral guidance. A kindergarten teacher could help enhance moral development by setting clear rules for the classroom, and the consequences for violating them. This helps kids at stage one of moral development.

A teacher in high school might focus more on the development that occurs in stage three (developing good interpersonal relationships) and stage four (maintaining social order). This could be accomplished by having the students take part in setting the rules to be followed in the classroom, giving them a better idea of the reasoning behind these rules.

Criticisms for Kohlberg's Theory of Moral Development

Kohlberg's theory played an important role in the development of moral psychology. While the theory has been highly influential, aspects of the theory have been critiqued for a number of reasons:

- Moral reasoning does not equal moral behavior : Kohlberg's theory is concerned with moral thinking, but there is a big difference between knowing what we ought to do versus our actual actions. Moral reasoning, therefore, may not lead to moral behavior.

- Overemphasizes justice : Critics have pointed out that Kohlberg's theory of moral development overemphasizes the concept of justice when making moral choices. Factors such as compassion, caring, and other interpersonal feelings may play an important part in moral reasoning.

- Cultural bias : Individualist cultures emphasize personal rights, while collectivist cultures stress the importance of society and community. Eastern, collectivist cultures may have different moral outlooks that Kohlberg's theory does not take into account.

- Age bias : Most of his subjects were children under the age of 16 who obviously had no experience with marriage. The Heinz dilemma may have been too abstract for these children to understand, and a scenario more applicable to their everyday concerns might have led to different results.

- Gender bias : Kohlberg's critics, including Carol Gilligan, have suggested that Kohlberg's theory was gender-biased since all of the subjects in his sample were male. Kohlberg believed that women tended to remain at the third level of moral development because they place a stronger emphasis on things such as social relationships and the welfare of others.

Gilligan instead suggested that Kohlberg's theory overemphasizes concepts such as justice and does not adequately address moral reasoning founded on the principles and ethics of caring and concern for others.

Other Theories of Moral Development

Kohlberg isn't the only psychologist to theorize how we develop morally. There are several other theories of moral development.

Piaget's Theory of Moral Development

Kohlberg's theory is an expansion of Piaget's theory of moral development. Piaget described a three-stage process of moral development:

- Stage 1 : The child is more concerned with developing and mastering their motor and social skills, with no general concern about morality.

- Stage 2 : The child develops unconditional respect both for authority figures and the rules in existence.

- Stage 3 : The child starts to see rules as being arbitrary, also considering an actor's intentions when judging whether an act or behavior is moral or immoral.

Kohlberg expanded on this theory to include more stages in the process. Additionally, Kohlberg believed that the final stage is rarely achieved by individuals whereas Piaget's stages of moral development are common to all.

Moral Foundations Theory

Proposed by Jonathan Haidt, Craig Joseph, and Jesse Graham, the moral foundations theory is based on three morality principles:

- Intuition develops before strategic reasoning . Put another way, our reaction comes first, which is then followed by rationalization.

- Morality involves more than harm and fairness . Contained within this second principle are a variety of considerations related to morality. It includes: care vs. harm, liberty vs. oppression, fairness vs. cheating, loyalty vs. betrayal , authority vs. subversion, and sanctity vs. degradation.

- Morality can both bind groups and blind individuals . When people are part of a group, they will tend to adopt that group's same value systems. They may also sacrifice their own morals for the group's benefit.

While Kohlberg's theory is primarily focused on help vs. harm, moral foundations theory encompasses several more dimensions of morality. However, this theory also fails to explain the "rules" people use when determining what is best for society.

Normative Theories of Moral Behavior

Several other theories exist that attempt to explain the development of morality , specifically in relation to social justice. Some fall into the category of transcendental institutionalist, which involves trying to create "perfect justice." Others are realization-focused, concentrating more on removing injustices.

One theory falling into the second category is social choice theory. Social choice theory is a collection of models that seek to explain how individuals can use their input (their preferences) to impact society as a whole. An example of this is voting, which allows the majority to decide what is "right" and "wrong."

See how much you've learned (or maybe already knew!) about Kohlberg's theory of moral development with this quick, free pop quiz.

While Kohlberg's theory of moral development has been criticized, the theory played an important role in the emergence of the field of moral psychology. Researchers continue to explore how moral reasoning develops and changes through life as well as the universality of these stages. Understanding these stages offers helpful insights into the ways that both children and adults make moral choices and how moral thinking may influence decisions and behaviors.

Lapsley D. Moral agency, identity and narrative in moral development . Hum Dev . 2010;53(2):87-97. doi:10.1159/000288210

Elorrieta-Grimalt M. A critical analysis of moral education according to Lawrence Kohlberg . Educación y Educadores . 2012;15(3):497-512. doi:10.5294/edu.2012.15.3.9

Govrin A. From ethics of care to psychology of care: Reconnecting ethics of care to contemporary moral psychology . Front Psychol . 2014;5:1135. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01135

American Psychological Association. Heinz dilemma .

American Psychological Association. Kohlberg's theory of moral development .

Kohlberg L, Essays On Moral Development . Harper & Row; 1985.

Ma HK. The moral development of the child: An integrated model . Front Public Health . 2013;1:57. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2013.00057

Gibbs J. Moral Development And Reality . 4th ed. Oxford University Press; 2019.

Gilligan C. In A Different Voice . Harvard University Press; 2016.

Patanella D. Piaget's theory of moral development . Encyclopedia of Child Behavior and Development . 2011. doi:10.1007/978-0-387-79061-9_2167

Dubas KM, Dubas SM, Mehta R. Theories of justice and moral behavior . J Legal Ethical Regulatory Issues . 2014;17(2):17-35.

By Kendra Cherry, MSEd Kendra Cherry, MS, is a psychosocial rehabilitation specialist, psychology educator, and author of the "Everything Psychology Book."

Kohlberg’s Stages of Moral Development

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

Key Takeaways

- Lawrence Kohlberg formulated a theory asserting that individuals progress through six distinct stages of moral reasoning from infancy to adulthood.

- He grouped these stages into three broad categories of moral reasoning, pre-conventional, conventional, and post-conventional. Each level is associated with increasingly complex stages of moral development.

- Kohlberg suggested that people move through these stages in a fixed order and that moral understanding is linked to cognitive development .

Heinz Dilemma

Lawrence Kohlberg (1958) agreed with Piaget’s (1932) theory of moral development in principle but wanted to develop his ideas further.

He used Piaget’s storytelling technique to tell people stories involving moral dilemmas. In each case, he presented a choice to be considered, for example, between the rights of some authority and the needs of some deserving individual unfairly treated.

After presenting people with various moral dilemmas, Kohlberg categorized their responses into different stages of moral reasoning.

Using children’s responses to a series of moral dilemmas, Kohlberg established that the reasoning behind the decision was a greater indication of moral development than the actual answer.

One of Kohlberg’s best-known stories (1958) concerns Heinz, who lived somewhere in Europe.

Heinz’s wife was dying from a particular type of cancer. Doctors said a new drug might save her. The drug had been discovered by a local chemist, and the Heinz tried desperately to buy some, but the chemist was charging ten times the money it cost to make the drug, and this was much more than the Heinz could afford. Heinz could only raise half the money, even after help from family and friends. He explained to the chemist that his wife was dying and asked if he could have the drug cheaper or pay the rest of the money later. The chemist refused, saying that he had discovered the drug and was going to make money from it. The husband was desperate to save his wife, so later that night he broke into the chemist’s and stole the drug. Should Heinz have broken into the laboratory to steal the drug for his wife? Why or why not?

Kohlberg asked a series of questions such as:

- Should Heinz have stolen the drug?

- Would it change anything if Heinz did not love his wife?

- What if the person dying was a stranger, would it make any difference?

- Should the police arrest the chemist for murder if the woman dies?

By studying the answers from children of different ages to these questions, Kohlberg hoped to discover how moral reasoning changed as people grew older.

The sample comprised 72 Chicago boys aged 10–16 years, 58 of whom were followed up at three-yearly intervals for 20 years (Kohlberg, 1984).

Each boy was given a 2-hour interview based on the ten dilemmas. Kohlberg was interested not in whether the boys judged the action right or wrong but in the reasons for the decision. He found that these reasons tended to change as the children got older.

Kohlberg identified three levels of moral reasoning: preconventional, conventional, and postconventional. Each level has two sub-stages.

People can only pass through these levels in the order listed. Each new stage replaces the reasoning typical of the earlier stage. Not everyone achieves all the stages.

Disequilibrium plays a crucial role in Kohlberg’s stages of moral development. A child encountering a moral issue may recognize limitations in their current reasoning approach, often prompted by exposure to others’ viewpoints. Improvements in perspective-taking are key to progressing through Kohlberg’s stages of moral development. As children mature, they increasingly understand issues from others’ viewpoints. For instance, a child at the preconventional level typically perceives an issue primarily in terms of personal consequences. In contrast, a child at the conventional level tends to consider the perspectives of others more substantially.

Level 1 – Preconventional Morality

Preconventional morality is the first level of moral development, lasting until approximately age 8. During this level, children accept the authority (and moral code) of others.

Preconventional morality is when people follow rules because they don’t want to get in trouble or they want to get a reward. This level of morality is mostly based on what authority figures like parents or teachers tell you to do rather than what you think is right or wrong.

Authority is outside the individual, and children often make moral decisions based on the physical consequences of actions.

For example, if an action leads to punishment, it must be bad; if it leads to a reward, it must be good.

So, people at this level don’t have their own personal sense of right and wrong yet. They think that something is good if they get rewarded for it and bad if they get punished for it.

For example, if you get candy for behaving, you think you were good, but if you get a scolding for misbehaving, you think you were bad.

At the preconventional level, children don’t have a personal code of morality. Instead, moral decisions are shaped by the standards of adults and the consequences of following or breaking their rules.

Stage 1. Obedience and Punishment Orientation . The child/individual is good to avoid being punished. If a person is punished, they must have done wrong.

Stage 2. Individualism and Exchange . At this stage, children recognize that there is not just one right view handed down by the authorities. Different individuals have different viewpoints.

Level 2 – Conventional Morality

Conventional morality is the adolescent phase of moral development focused on societal norms and external expectations to discern right from wrong, often grounded in tradition, cultural practices, or established codes of conduct.

We internalize the moral standards of valued adult role models at the conventional level (most adolescents and adults).

Authority is internalized but not questioned, and reasoning is based on the group’s norms to which the person belongs.

A social system that stresses the responsibilities of relationships and social order is seen as desirable and must influence our view of right and wrong.

So, people who follow conventional morality believe that it’s important to follow society’s rules and expectations to maintain order and prevent problems.

For example, refusing to cheat on a test is a part of conventional morality because cheating can harm the academic system and create societal problems.

Stage 3. Good Interpersonal Relationships . The child/individual is good to be seen as being a good person by others. Therefore, answers relate to the approval of others.

Stage 4. Law and Order Morality . The child/individual becomes aware of the wider rules of society, so judgments concern obeying the rules to uphold the law and avoid guilt.

Level 3 – Postconventional Morality

Postconventional morality is the third level of moral development and is characterized by an individual’s understanding of universal ethical principles.

Postconventional morality is when people decide based on what they think is right rather than just following the rules of society. This means that people at this level of morality have their own ethical principles and values and don’t just do what society tells them to do.

At this level, people think about what is fair, what is just, and what values are important.

What is considered morally acceptable in any given situation is determined by what is the response most in keeping with these principles.

They also think about how their choices might affect others and try to make good decisions for everyone, not just themselves.

Values are abstract and ill-defined but might include: the preservation of life at all costs and the importance of human dignity. Individual judgment is based on self-chosen principles, and moral reasoning is based on individual rights and justice.

According to Kohlberg, this level of moral reasoning is as far as most people get.

Only 10-15% are capable of abstract thinking necessary for stage 5 or 6 (post-conventional morality). That is to say, most people take their moral views from those around them, and only a minority think through ethical principles for themselves.

Stage 5. Social Contract and Individual Rights . The child/individual becomes aware that while rules/laws might exist for the good of the greatest number, there are times when they will work against the interest of particular individuals. The issues are not always clear-cut. For example, in Heinz’s dilemma, the protection of life is more important than breaking the law against stealing.

Stage 6. Universal Principles . People at this stage have developed their own set of moral guidelines, which may or may not fit the law. The principles apply to everyone. E.g., human rights, justice, and equality. The person will be prepared to act to defend these principles even if it means going against the rest of society in the process and having to pay the consequences of disapproval and or imprisonment. Kohlberg doubted few people had reached this stage.

Problems with Kohlberg’s Methods

1. the dilemmas are artificial (i.e., they lack ecological validity).

Most dilemmas are unfamiliar to most people (Rosen, 1980). For example, it is all very well in the Heinz dilemma, asking subjects whether Heinz should steal the drug to save his wife.

However, Kohlberg’s subjects were aged between 10 and 16. They have never been married, and never been placed in a situation remotely like the one in the story.

How should they know whether Heinz should steal the drug?

2. The sample is biased

Kohlberg’s (1969) theory suggested males more frequently progress beyond stage four in moral development, implying females lacked moral reasoning skills.

His research assistant, Carol Gilligan, disputed this, who argued that women’s moral reasoning differed, not deficient.

She criticized Kohlberg’s theory for focusing solely on upper-class white males, arguing women value interpersonal connections. For instance, women often oppose theft in the Heinz dilemma due to potential repercussions, such as separation from his wife if Heinz is imprisoned.

Gilligan (1982) conducted new studies interviewing both men and women, finding women more often emphasized care, relationships and context rather than abstract rules. Gilligan argued that Kohlberg’s theory overlooked this relational “different voice” in morality.

According to Gilligan (1977), because Kohlberg’s theory was based on an all-male sample, the stages reflect a male definition of morality (it’s androcentric).

Men’s morality is based on abstract principles of law and justice, while women’s is based on principles of compassion and care.

Further, the gender bias issue raised by Gilligan is a reminder of the significant gender debate still present in psychology, which, when ignored, can greatly impact the results obtained through psychological research.

3. The dilemmas are hypothetical (i.e., they are not real)

Kohlberg’s approach to studying moral reasoning relied heavily on his semi-structured moral judgment interview. Participants were presented with hypothetical moral dilemmas, and their justifications were analyzed to determine their stage of moral reasoning.

Some critiques of Kohlberg’s method are that it lacks ecological validity, removes reasoning from real-life contexts, and defines morality narrowly in terms of justice reasoning.

Psychologists concur with Kohlberg’s moral development theory, yet emphasize the difference between moral reasoning and behavior.

What we claim we’d do in a hypothetical situation often differs from our actions when faced with the actual circumstance. In essence, our actions might not align with our proclaimed values.

In a real situation, what course of action a person takes will have real consequences – and sometimes very unpleasant ones for themselves. Would subjects reason in the same way if they were placed in a real situation? We don’t know.

The fact that Kohlberg’s theory is heavily dependent on an individual’s response to an artificial dilemma questions the validity of the results obtained through this research.

People may respond very differently to real-life situations that they find themselves in than they do to an artificial dilemma presented to them in the comfort of a research environment.

4. Poor research design

How Kohlberg carried out his research when constructing this theory may not have been the best way to test whether all children follow the same sequence of stage progression.

His research was cross-sectional , meaning that he interviewed children of different ages to see their moral development level.

A better way to see if all children follow the same order through the stages would be to conduct longitudinal research on the same children.

However, longitudinal research on Kohlberg’s theory has since been carried out by Colby et al. (1983), who tested 58 male participants of Kohlberg’s original study.

She tested them six times in 27 years and supported Kohlberg’s original conclusion, which is that we all pass through the stages of moral development in the same order.

Contemporary research employs more diverse methods beyond Kohlberg’s interview approach, such as narrative analysis, to study moral experience. These newer methods aim to understand moral reasoning and development within authentic contexts and experiences.

- Tappan and colleagues (1996) promote a narrative approach that examines how individuals construct stories and identities around moral experiences. This draws from the sociocultural tradition of examining identity in context. Tappan argues narrative provides a more contextualized understanding of moral development.

- Colby and Damon’s (1992) empirical research uses in-depth life story interviews to study moral exemplars – people dedicated to moral causes. Instead of hypothetical dilemmas, they ask participants to describe real moral challenges and commitments. Their goal is to respect exemplars as co-investigators of moral meaning-making.

- Walker and Pitts’ (1995) studies use open-ended interviews asking people to discuss real-life moral dilemmas and reflect on the moral domain in their own words. This elicits more naturalistic conceptions of morality compared to Kohlberg’s abstract decontextualized approach.

Problems with Kohlberg’s Theory

1. are there distinct stages of moral development.

Kohlberg claims there are, but the evidence does not always support this conclusion.

For example, a person who justified a decision based on principled reasoning in one situation (postconventional morality stage 5 or 6) would frequently fall back on conventional reasoning (stage 3 or 4) with another story.

In practice, it seems that reasoning about right and wrong depends more on the situation than on general rules. Moreover, individuals do not always progress through the stages, and Rest (1979) found that one in fourteen slipped backward.

The evidence for distinct stages of moral development looks very weak. Some would argue that behind the theory is a culturally biased belief in the superiority of American values over those of other cultures and societies.

Gilligan (1982) did not dismiss developmental psychology or morality. She acknowledged that children undergo moral development in stages and even praised Kohlberg’s stage logic as “brilliant” (Jorgensen, 2006, p. 186). However, she preferred Erikson’s model over the more rigid Piagetian stages.

While Gilligan supported Kohlberg’s stage theory as rational, she expressed discomfort with its structural descriptions that lacked context.

She also raised concerns about the theory’s universality, pointing out that it primarily reflected Western culture (Jorgensen, 2006, pp. 187-188).

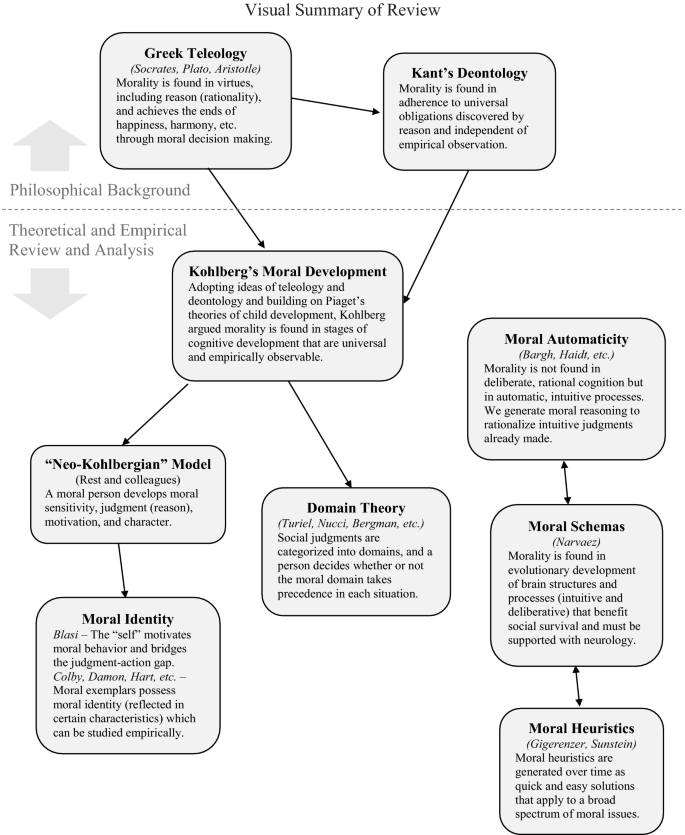

Neo-Kohlbergian Schema Model

Rest and colleagues (199) have developed a theoretical model building on but moving beyond Kohlberg’s stage-based approach to moral development. Their model outlines four components of moral behavior: moral sensitivity, moral judgment, moral motivation, and moral character.

For the moral judgment component, Rest et al. propose that individuals use moral schemas rather than progress through discrete stages of moral reasoning.

Schemas are generalized knowledge structures that help us interpret information and situations. An individual can have multiple schemas available to make sense of moral issues, rather than being constrained to a single developmental stage.

Some examples of moral schemas proposed by Rest and colleagues include:

- Personal Interest Schema – focused on individual interests and preferences

- Maintaining Norms Schema – emphasizes following rules and norms

- Postconventional Schema – considers moral ideals and principles

Rather than viewing development as movement to higher reasoning stages, the neo-Kohlbergian approach sees moral growth as acquiring additional, more complex moral schemas. Lower schemas are not replaced, but higher order moral schemas become available to complement existing ones.

The schema concept attempts to address critiques of the stage model, such as its rigidity and lack of context sensitivity. Using schemas allows for greater flexibility and integration of social factors into moral reasoning.

2. Does moral judgment match moral behavior?

Kohlberg never claimed that there would be a one-to-one correspondence between thinking and acting (what we say and what we do), but he does suggest that the two are linked.

However, Bee (1994) suggests that we also need to take into account of:

a) habits that people have developed over time. b) whether people see situations as demanding their participation. c) the costs and benefits of behaving in a particular way. d) competing motive such as peer pressure, self-interest and so on.

Overall, Bee points out that moral behavior is only partly a question of moral reasoning. It also has to do with social factors.

3. Is justice the most fundamental moral principle?

This is Kohlberg’s view. However, Gilligan (1977) suggests that the principle of caring for others is equally important. Furthermore, Kohlberg claims that the moral reasoning of males has often been in advance of that of females.

Girls are often found to be at stage 3 in Kohlberg’s system (good boy-nice girl orientation), whereas boys are more often found to be at stage 4 (Law and Order orientation). Gilligan (p. 484) replies:

“The very traits that have traditionally defined the goodness of women, their care for and sensitivity to the needs of others, are those that mark them out as deficient in moral development”.

In other words, Gilligan claims that there is a sex bias in Kohlberg’s theory. He neglects the feminine voice of compassion, love, and non-violence, which is associated with the socialization of girls.

Gilligan concluded that Kohlberg’s theory did not account for the fact that women approach moral problems from an ‘ethics of care’, rather than an ‘ethics of justice’ perspective, which challenges some of the fundamental assumptions of Kohlberg’s theory.

In contrast to Kohlberg’s impersonal “ethics of justice”, Gilligan proposed an alternative “ethics of care” grounded in compassion and responsiveness to needs within relationships (Gilligan, 1982).

Her care perspective highlights emotion, empathy and understanding over detached logic. Gilligan saw care and justice ethics as complementary moral orientations.

Walker et al. (1995) found everyday moral conflicts often revolve around relationships rather than justice; individuals describe relying more on intuition than moral reasoning in dilemmas. This raises questions about the centrality of reasoning in moral functioning.

4. Do people make rational moral decisions?

Kohlbeg’s theory emphasizes rationality and logical decision-making at the expense of emotional and contextual factors in moral decision-making.

One significant criticism is that Kohlberg’s emphasis on reason can create an image of the moral person as cold and detached from real-life situations.

Carol Gilligan critiqued Kohlberg’s theory as overly rationalistic and not accounting for care-based morality commonly found in women. She argued for a “different voice” grounded in relationships and responsiveness to particular individuals.

The criticism suggests that by portraying moral reasoning as primarily cognitive and detached from emotional and situational factors, Kohlberg’s theory oversimplifies real-life moral decision-making, which often involves emotions, social dynamics, cultural nuances, and practical constraints.

Critics contend that his model does not adequately capture the multifaceted nature of morality in the complexities of everyday life.

Bee, H. L. (1994). Lifespan development . HarperCollins College Publishers.

Blum, L. A. (1988). Gilligan and Kohlberg: Implications for moral theory. Ethics , 98 (3), 472-491.

Colby, A., Kohlberg, L., Gibbs, J., & Lieberman, M. (1983). A longitudinal study of moral judgment. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development , 48 (1-2, Serial No. 200). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Day, J. M., & Tappan, M. B. (1996). The narrative approach to moral development: From the epistemic subject to dialogical selves. Human Development , 39 (2), 67-82.

Gilligan, C. (1977). In a different voice: Women’s conceptions of self and of morality. Harvard Educational Review , 47(4), 481-517.

Gilligan, C. (1982). In a different voice . Harvard University Press.

Gilligan, C. (1995). Hearing the difference: Theorizing connection. Hypatia, 10 (2), 120-127.

Jorgensen, G. (2006). Kohlberg and Gilligan: duet or duel?. Journal of Moral Education , 35 (2), 179-196.

Kohlberg, L. (1958). The Development of Modes of Thinking and Choices in Years 10 to 16. Ph. D. Dissertation , University of Chicago.

Kohlberg, L. (1984). The Psychology of Moral Development: The Nature and Validity of Moral Stages (Essays on Moral Development, Volume 2) . Harper & Row

Piaget, J. (1932). The moral judgment of the child . London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co.

Rest, J. R. (1979). Development in judging moral issues . University of Minnesota Press.

Rosen, B. (1980). Moral dilemmas and their treatment. In, Moral development, moral education, and Kohlberg. B. Munsey (Ed). (1980), pp. 232-263. Birmingham, Alabama: Religious Education Press.

Walker, L. J., Pitts, R. C., Hennig, K. H., & Matsuba, M. K. (1995). Reasoning about morality and real-life moral problems.

Further Information

- BBC Radio 4: The Heinz Dilemma

- The Science of Morality

- Piaget’s Theory of Moral Development

What is an example of moral development theory in real life?

An example is a student who witnesses cheating on an important exam. The student is faced with the dilemma of whether to report the cheating or keep quiet.

A person at the pre-conventional level of moral development might choose not to report cheating because they fear the consequences or because they believe that everyone cheats.

A person at the conventional level might report cheating because they believe it is their duty to uphold the rules and maintain fairness in the academic environment.

A person at the post-conventional level might weigh the ethical implications of both options and make a decision based on their principles and values, such as honesty, fairness, and integrity, even if it may come with negative consequences.

This example demonstrates how moral development theory can help us understand how individuals reason about ethical dilemmas and make decisions based on their moral reasoning.

What are the examples of stage 6 universal principles?

Stage 6 of Kohlberg’s moral development theory, also known as the Universal Ethical Principles stage, involves moral reasoning based on self-chosen ethical principles that are comprehensive and consistent. Examples might include:

Equal human rights : Someone at this stage would believe in the fundamental right of all individuals to life, liberty, and fair treatment. They would advocate for and act according to these rights, even if it meant opposing laws or societal norms.

Justice for all : A person at this stage believes in justice for all individuals and would strive to ensure fairness in all situations. For example, they might campaign against a law they believe to be unjust, even if it is widely accepted by society.

Non-violence : A commitment to non-violence could be a universal principle for some at this stage. For instance, they might choose peaceful protest or civil disobedience in the face of unjust laws or societal practices.

Social contract : People at this stage might also strongly believe in the social contract, wherein individuals willingly sacrifice some freedoms for societal benefits. However, they also understand that these societal norms can be challenged and changed if they infringe upon the universal rights of individuals.

Respect for human dignity and worth : Individuals at this stage view each person as possessing inherent value, and this belief guides their actions and judgments. They uphold the dignity and worth of every individual, regardless of social status or circumstance.

What is the Kohlberg’s Heinz dilemma?

The Heinz dilemma is a moral question proposed by Kohlberg in his studies on moral development. It involves a man named Heinz who considers stealing a drug he cannot afford to save his dying wife, prompting discussion on the moral implications and justifications of his potential actions.

Related Articles

Child Psychology

Vygotsky vs. Piaget: A Paradigm Shift

Interactional Synchrony

Internal Working Models of Attachment

Soft Determinism In Psychology

Branches of Psychology

Learning Theory of Attachment

Ethics and Morality

Morality, Ethics, Evil, Greed

Reviewed by Psychology Today Staff

To put it simply, ethics represents the moral code that guides a person’s choices and behaviors throughout their life. The idea of a moral code extends beyond the individual to include what is determined to be right, and wrong, for a community or society at large.

Ethics is concerned with rights, responsibilities, use of language, what it means to live an ethical life, and how people make moral decisions. We may think of moralizing as an intellectual exercise, but more frequently it's an attempt to make sense of our gut instincts and reactions. It's a subjective concept, and many people have strong and stubborn beliefs about what's right and wrong that can place them in direct contrast to the moral beliefs of others. Yet even though morals may vary from person to person, religion to religion, and culture to culture, many have been found to be universal, stemming from basic human emotions.

- The Science of Being Virtuous

- Understanding Amorality

- The Stages of Moral Development

Those who are considered morally good are said to be virtuous, holding themselves to high ethical standards, while those viewed as morally bad are thought of as wicked, sinful, or even criminal. Morality was a key concern of Aristotle, who first studied questions such as “What is moral responsibility?” and “What does it take for a human being to be virtuous?”

We used to think that people are born with a blank slate, but research has shown that people have an innate sense of morality . Of course, parents and the greater society can certainly nurture and develop morality and ethics in children.

Humans are ethical and moral regardless of religion and God. People are not fundamentally good nor are they fundamentally evil. However, a Pew study found that atheists are much less likely than theists to believe that there are "absolute standards of right and wrong." In effect, atheism does not undermine morality, but the atheist’s conception of morality may depart from that of the traditional theist.

Animals are like humans—and humans are animals, after all. Many studies have been conducted across animal species, and more than 90 percent of their behavior is what can be identified as “prosocial” or positive. Plus, you won’t find mass warfare in animals as you do in humans. Hence, in a way, you can say that animals are more moral than humans.

The examination of moral psychology involves the study of moral philosophy but the field is more concerned with how a person comes to make a right or wrong decision, rather than what sort of decisions he or she should have made. Character, reasoning, responsibility, and altruism , among other areas, also come into play, as does the development of morality.

The seven deadly sins were first enumerated in the sixth century by Pope Gregory I, and represent the sweep of immoral behavior. Also known as the cardinal sins or seven deadly vices, they are vanity, jealousy , anger , laziness, greed, gluttony, and lust. People who demonstrate these immoral behaviors are often said to be flawed in character. Some modern thinkers suggest that virtue often disguises a hidden vice; it just depends on where we tip the scale .

An amoral person has no sense of, or care for, what is right or wrong. There is no regard for either morality or immorality. Conversely, an immoral person knows the difference, yet he does the wrong thing, regardless. The amoral politician, for example, has no conscience and makes choices based on his own personal needs; he is oblivious to whether his actions are right or wrong.

One could argue that the actions of Wells Fargo, for example, were amoral if the bank had no sense of right or wrong. In the 2016 fraud scandal, the bank created fraudulent savings and checking accounts for millions of clients, unbeknownst to them. Of course, if the bank knew what it was doing all along, then the scandal would be labeled immoral.

Everyone tells white lies to a degree, and often the lie is done for the greater good. But the idea that a small percentage of people tell the lion’s share of lies is the Pareto principle, the law of the vital few. It is 20 percent of the population that accounts for 80 percent of a behavior.

We do know what is right from wrong . If you harm and injure another person, that is wrong. However, what is right for one person, may well be wrong for another. A good example of this dichotomy is the religious conservative who thinks that a woman’s right to her body is morally wrong. In this case, one’s ethics are based on one’s values; and the moral divide between values can be vast.

Psychologist Lawrence Kohlberg established his stages of moral development in 1958. This framework has led to current research into moral psychology. Kohlberg's work addresses the process of how we think of right and wrong and is based on Jean Piaget's theory of moral judgment for children. His stages include pre-conventional, conventional, post-conventional, and what we learn in one stage is integrated into the subsequent stages.

The pre-conventional stage is driven by obedience and punishment . This is a child's view of what is right or wrong. Examples of this thinking: “I hit my brother and I received a time-out.” “How can I avoid punishment?” “What's in it for me?”

The conventional stage is when we accept societal views on rights and wrongs. In this stage people follow rules with a good boy and nice girl orientation. An example of this thinking: “Do it for me.” This stage also includes law-and-order morality: “Do your duty.”

The post-conventional stage is more abstract: “Your right and wrong is not my right and wrong.” This stage goes beyond social norms and an individual develops his own moral compass, sticking to personal principles of what is ethical or not.

However well-intended, our empathy and support can have a paradoxical effect. We can fail to take others seriously or appreciate their suffering as a response to moral demands.

Personal Perspective: Life can be more than continually grabbing as much as we can for ourselves. Let's fight back with courtesy and respect the needs of others.

As a father of an autistic child and a researcher on neurodiversity, I propose we model political interactions after productive relationships with neurodivergent family members.

Debt is incredibly common, yet we often do not discuss its impact. Moralizing debt can create isolation and shameful feelings.

Recognizing our shared humanity can counter injustice and harm and help bring peace to our hearts.

A client is getting on your nerves. You feel it’s not good for your mental health to continue to work with them. How can you terminate work without incurring a malpractice lawsuit?

Accountability is the virtue of answerability. It involves trust, but not blind trust. It claims both successes and failures. In sports, it makes us hard to beat.

Let's say you don’t think it’s good for your mental health to continue working with a particular client. How can you terminate work without being sued for malpractice?

Navigating the delicate balance between selflessness and self-interest. From the evolutionary roots of altruism to its modern-day manifestations.

How well do scientists know how effectively they apply research ethics? Probably not so well, but that should come as no surprise.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Self Tests NEW

- Therapy Center

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

At any moment, someone’s aggravating behavior or our own bad luck can set us off on an emotional spiral that threatens to derail our entire day. Here’s how we can face our triggers with less reactivity so that we can get on with our lives.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

Access your Commentary account.

Lost your password? Please enter your email address. You will receive a link to create a new password via email.

The monthly magazine of opinion.

Essays on Moral Development, by Lawrence Kohlberg

Essays on Moral Development, Volume One: The Philosophy of Moral Development. by Lawrence Kohlberg. Harper & Row. 441 pp. $21.95.

Lawrence Kohlberg is a Harvard psychologist who has been insisting for two decades that the study of children’s moral reasoning can guide society in distinguishing right from wrong. His work has been influential—it has supplied much of the impetus behind “moral education” courses that are appearing even in elementary schools. The present collection of essays is concerned with the moral and pedagogical consequences Kohlberg draws from his empirical findings about children, from cross-cultural studies, and from “longitudinal” studies of given subjects at different ages.

Kohlberg discerns six “stages of moral development.” The first four are uncontroversial, extending from the child’s obedience out of fear of punishment to the “my station and its duties” mentality attributed to J. Edgar Hoover. Stage 5, the “official morality of the U.S. Constitution,” recognizes obligations based on contract, plus basic rights like life and liberty. Stage 6—to which this book is a sustained hosannah—adds “justice,” interpreted as “rationally demonstrable universal ethical principles” based on “respect for the dignity of human beings as individuals.”

What distinguishes stage 6 from stage 5 is, in effect, the willingness to disobey laws that conflict with these principles. Kohlberg estimates the number of stage 6’s to be 5 percent of the American population, but his only sustained example of a 6 is Martin Luther King, Jr. Socrates sometimes rates a 6, but is elsewhere demoted to a “5B,” apparently for taking the laws of Athens too seriously. (Kohlberg repeatedly compares King with Socrates as a “moral teacher” executed by the society he made uncomfortable, as if James Earl Ray were a legally appointed executioner.) Lincoln and Gandhi are accorded 6’s in passing.

_____________

What makes a later stage a higher stage? Part of Kohlberg’s answer is the irreversibility of the sequence of stages: while most people become “fixed” at a stage lower than 6, no one ever retreats from a later stage to an earlier one. Ultimately, however, Kohlberg equates later with better because, he says, each stage resolves conflicts that remain unresolved at earlier stages. Thus, Kohlberg reports that his stage-5 respondents disagreed among themselves about whether a man may steal an expensive drug to save his wife’s life, whereas his stage-6 respondents unanimously approved of stealing the drug. Stage 6 is hence the summit of morality because it is the most “formally adequate,” “integrated” level of morality. Not only does it address every moral dilemma, but all who reach it will agree in their answers.

Kohlberg defends this patent absurdity—Socrates, King, Lincoln, and Gandhi would hardly have seen eye-to-eye about, say, homosexuality—by referring to John Rawls’s A Theory of Justice , “the newest great book of the liberal tradition,” which “systematically justifies” stage 6. In resting his own case on Rawls’s, Kohlberg is virtually asking the non-philosophical reader to accept his claims about stage 6 on faith. Still, the basic outlines of Kohlberg’s position are clear.

According to Rawls, when you truly apply the Golden Rule to a problem, you are not distracted by your own preferences or the natural human tendency to put your own interests first. The principles you come up with will be genuinely fair, or just, principles. Rawls’s basic idea is to devise a model situation in which people are really thinking along golden-rule lines. He has us picture rational egoists who have temporarily forgotten their actual places in society. In deliberating about principles that will govern their society, such self-regarding amnesiacs would imagine a principle’s impact on people of every status, and so not slight any person or position, however humble. And Rawls adds an extra twist: his egoists pay most heed to how the worst off will fare, since (for reasons Rawls never quite clarifies) each is obsessively afraid that he will turn out to be the worst off when the “veil of ignorance” lifts.

Kohlberg illustrates the supposedly computer-like operation of this “method of musical chairs” with the issue of capital punishment. Rawls’s model people would reject it, he says, because, while each recognizes the deterrent advantages of capital punishment, each thinks, “what if I were a murderer?” Each then realizes that the murderer would not want to be executed, and hence renounces capital punishment. Lest the reader accuse me of imputing to Kohlberg a position too preposterous for anyone to maintain, here are his own words: If we “assess the death penalty from the point of view of someone who takes into account the possibility of being a capital offender himself [we see that] the capital offender, obviously, would claim that he should be allowed to remain alive. . . . In short, at stage 6 the rational capital offender’s claim to life would be given priority over the claim of maximal protection from crime asserted by the representative ordinary citizen.”

Something has gone wrong. Kohlberg’s magical argument against capital punishment really works against any punishment; presumably he would repudiate parking tickets for according double-parkers insufficient respect. Kohlberg has apparently confused what one would want in a difficult situation with what one would claim he should be allowed to have. Were I a murderer in the electric chair I would hope for a pardon, a power failure, or anything else that would save me, but I would hardly suppose I had a “rational claim” to a right to live that offset the claims of innocents saved by my execution.

This confusion between what people would be willing to do and what they would claim a right to do skews Kohlberg’s understanding of the drug-stealing case, which he sees as a collision between “capitalist morality” and the “sacredness of life.” While it is true that I would stick at almost nothing to save my wife’s life, I would never claim a right on my part or my wife’s to do what I would do. Nor would I do those things to save a stranger, even though, on Kohlberg’s view, the issue involves a generalized right to life the stranger shares with my wife. (I think my attitude makes me a 3.)

Actually, far from resolving every hard problem, “equal respect under universal principles of justice” is an empty truism. Should Churchill warn Coventry about the planned Nazi bombing or remain silent to protect the secret that the British had cracked the Enigma code? Can British counterespionage frame an honorable U-boat captain to damage German morale? Any choice dooms someone, and avoiding the problem (“I don’t want anybody’s blood on my hands”) amounts to choosing to spare the captain and risk extra Allied lives. Whatever the solutions to such dilemmas, the incantation of “equal respect for everyone” will not reveal them.

Indeed, it quickly becomes clear that Kohlberg is just making up stage 6 as he goes along. He scales the peak of arbitrariness when he counsels a stage-6 wife dying of cancer to concur in her own mercy killing: “If the wife puts herself in the husband’s place, the grief she anticipates about her own death is more than matched by the grief a husband should feel at her pain.” Kohlberg does not disclose how to determine the pain the wife will feel, the pain the husband “should” feel, or, indeed, what has become of the “sacredness of life.”

In fact, there is no stage 6. Kohlberg fudges this by combining stages 5 and 6 in his statistics. Astonishingly, he admits in a candid paragraph that

our empirical findings do not clearly delineate a sixth stage. . . . None of our longitudinal subjects have reached the highest stage. Our examples of stage 6 come either from historical figures [conveniently unavailable for answering questionnaires] or from interviews with people who have extensive philosophic training. . . . Stage 6 is perhaps less a statement of an attained psychological reality than the specification of a direction in which, our theory claims, ethical development is moving.

This trumpery shows Kohlberg’s program of “moral education” for the instrument of propaganda it really is. Kohlberg’s proposal begins modestly enough, with Dewey’s insight that children learn best when challenged by problems that strain their current concepts. To this Kohlberg adds Piaget’s discovery that certain key concepts are learned only in a definite order of maturation. What results is a general educational strategy of helping children through natural cognitive stages by posing stimulating problems. Kohlberg now applies this to morals: since a child is disposed to pass through the levels of morality anyway, the teacher should boost him along with provocative tales about theft and murder.

Kohlberg dismisses the idea that schools, especially public schools, should leave ethics to others with the admonition that a “hidden moral curriculum”—of conformity—always lurks behind official postures of neutrality. But Kohlberg’s own pedagogy is anything but the Socratic midwife to a child’s autonomy. Those tales of mercy killings and the like, a “hidden moral curriculum” if there ever was one, are designed to push children along a specific policy agenda that has nothing to do with any natural bents, let alone with “rationally demonstrable universal ethical principles.”

Beneath the platitudes and the jargon, Kohlberg’s morality comes to a specious egalitarianism. It is hard to believe Kohlberg really thinks that any desire, however base or outrageous, deserves as much “respect”—i.e., satisfaction—as any other. But whatever “stage-6 morality” is, it is not synonymous with respect for persons as understood in the Kantian moral tradition Kohl-berg claims to be following. Kantian respect means allowing each person to choose his actions freely and to accept the consequences of his choices. Such respect has nothing to do with satisfying the desires of the autonomous beings who are said to deserve it.

After interviewing a captured Nazi, the hero of Nicholas Monsarrat’s autobiographical novel The Cruel Sea thinks to himself, “These people are not curable. We’ll just have to shoot them and hope for a better crop next time.” Hardly stage-6 thinking—which is why today I am alive to write this and you to read it.

Joan Didion From the Couch

Brush Off Your Shakespeare

Joseph Epstein’s Brief for the Novel

Scroll Down For the Next Article

Type and press enter

- More Networks

99 Moral Development Essay Topic Ideas & Examples

🏆 best moral development topic ideas & essay examples, 📌 simple & easy moral development essay titles, 👍 good essay topics on moral development, ❓ questions about moral development.

- School Bullying and Moral Development The middle childhood is marked by the development of basic literacy skills and understanding of other people’s behavior that would be crucial in creating effective later social cognitions. Therefore, addressing bullying in schools requires strategies […]

- Kohlberg’s Stages of Moral Development in Justice System Burglars, whose predominant level of morality is conventional, tend to consider the opinion of the society on their actions. Kohlberg’s stages of moral development help to identify the problems and find solutions to them.

- Kohlberg’s Moral Development Concept This is continuous because, in every stage of the moral development, the moral reasoning changes to become increasingly complex over the years.

- Moral Development in Early Childhood The only point to be poorly addressed in this discussion is the options for assessing values in young children and the worth of this task.

- The Moral Development of Children Child development Rev 2000; 71: 1033 1048.’ moral development/moral reasoning which is an important aspect of cognitive development of children has been studied very thoroughly with evidence-based explanations from the work of many psychologists based […]

- Pulp Fiction: Moral Development of American Life and Interests Quentin Tarantino introduces his Pulp Fiction by means of several scenes which have a certain sequence: proper enlightenment, strong and certain camera movements and shots, focus on some details and complete ignorance of the others, […]

- An Evaluation of Kohlberg’s Theory of Moral Development and How It Could Be Applied to Grade School It is the purpose of this essay to summarize Kohlberg’s theory, and thereafter analyze how the theory can be applied to grade a school.

- Moral Development and Bullying in Children The understanding of moral development following the theories of Kohlberg and Gilligan can provide useful solutions to eliminating bullying in American schools.

- Moral Development and Its Relation to Psychology These stages reveal the individual’s moral orientation expanding his/her experiences and perceptions of the world with regard to the cognitive development of a person admitting this expansion. The views of Piaget and Kohlberg differ in […]

- Kohlberg’s Theory of Moral Development Dilemma According to Kohlberg, justice is the driver of the process of moral development. Therefore, the early Christians should have continued to practice Christianity regardless of the persecution.

- Moral Development: Emotion and Moral Behavior More moral emotion is guilt as compared to shame because those who are shamed are relatively unlikely to rectify as compared to the guilty people.

- Adolescent Moral Development in the United States Adolescents who are in this stage begin to acknowledge and understand the beliefs embraced in their societies. The absence of a moral compass can make it hard for adolescents in this country to realize their […]

- Moral Development Theory Review by Kohlberg and Hersh Overall, the main strength of this article is that the authors present a comprehensive overview of theories that can throw light on the moral development of a person.

- Moral Development and Aggression The reason is that children conclude about the acceptability of aggressive or violent behaviors with reference to what they see and hear in their family and community.

- Moral Development: Kohlberg’s Dilemmas Another characteristic of this stage of moral speculation is that the speculators mostly view the dilemma through the lens of consequences it might result in and engage them in a direct or indirect manner.

- Chinese Foundations for Moral Education and Character Development In Chinese Foundations for Moral Education and Character Development, Vincent Shen and his team make a wonderful attempt to describe how rich and captivating Chinese cultural heritage may be, how considerable knowledge for this country […]

- Cognitive, Psychosocial, Psychosexual and Moral Development This, he goes ahead to explain that it is at this very stage that children learn to be self sufficient in terms of taking themselves to the bathroom, feeding and even walking.

- Moral Development and Ethical Concepts The two concepts are important in the promotion of ethical culture within the organizations, the organizations’ performance and the much needed moral and financial support from the organization’s stakeholders and the public in general.

- Empathy and Moral Development For a manager to have empathy, he/she has to be able to interact freely with the employees, and spend time with them at their work places. This makes the employees to know that what they […]

- Cognitive or Moral Development This is the second of the four Piagetian stages of development and the children begin to make use of words, pictures and diagrams to represent their sentiments.

- Moral Intelligence Development In the course of his day-to-day banking activities, I realized that the general manager used to work in line with the banking rules and regulations to the letter.

- The Impact Of Television On The Moral Development

- Influences in Moral Development

- The Influence of Parenting in the Moral Development of a Child

- The Effect of Cognitive Moral Development on Honesty in Managerial Reporting

- Huckleberry Finn Moral Development & Changes

- Responsibility For Moral Development In Children

- Morality and Responsibility – Moral Development in Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein

- Moral Development And Gender Care Theories

- Jean Piaget and Lawrence Kohlberg on Moral Development

- Kaylee Georgeoff’s Moral Development According To Lawrence Kohlberg

- The Criticisms Of Kohlberg’s Moral Development Stages

- The Ethics Of The Organization ‘s Moral Development

- Lawrence Kohlbergs Stages Of Moral Development

- Personal, Psychosocial, And Moral Development Theories

- Moral Development and Importance of Moral Reasoning

- Integrating Care and Justice: Moral Development

- Moral Development in Youth Sport

- Kohlberg’s Theory on Moral Development: New Field of Study in Western Science

- The Definition of Ethics and the Foundation of Moral Development

- Kohleberg´s Philosophy of Moral Development

- Stealing and Moral Reasoning: Kohlberg’s Stages of Moral Development

- Plagiarism and Moral Development

- Kohlberg and Moral Development Between the Ages of One and Six

- Kohlberg’s 6 Stages of Cognitive Moral Development and Model Suggestions

- Moral Development and Narcissism of Private and Public University Business Students

- The Effect of the Transcendental Meditation TM Technique on Moral Development

- Psychology Stages of Moral Development

- The Link Between Friendship and Moral Development

- Moral Development And Gender Related Reasoning Styles

- Moral Development in the Adventures of Huckleberry Fin by Mark Twain

- Moral Development : The Way Someone Thinks, Feels, And Behaves

- The Effect of Nuclear and Joint Family Systems on the Moral Development: A Gender Based Analysis

- Moral Development and Dilemmas of Huck in The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn by Mark Twain

- Teaching Moral Development To School Children In The Caribbean

- History and Moral Development of Mental Health Treatment and Involuntary Commitment

- Incorporating Kohlberg’s Stages of Moral Development into the Justice System

- Moral Development Theory in Boys and Girls: Kohlberg and Gilligan

- The Different Levels in Moral Development

- Moral Development Of Six-Year-Old Children

- Portrait of Erik Erikson’s Developmental Theory and Kohlberg’s Model of Moral Development

- Moral Development Of Jem And Scout In To Kill A Mockingbird

- Moral Development and Aggression in Children

- The Idea Of Moral Development In The Novel Adventures of Huckleberry Finn By Mark Twain

- The Influence of Media Technology on the Moral Development and Self-Concept of Youth

- The Character of Tituba in Lawrence Kohlberg’s Different Stages of Moral Development

- Multiple Intelligences, Metacognition And Moral Development

- Moral Development : The Foundation Of Ethical Behavior

- Can Moral Development Lead To Upward Influence Behavior?

- What Are the Five Stages of Moral Development?

- What Is an Example of Moral Development?

- What Is Moral Development, and Why Is It Important?

- What Are the Three Levels of Moral Development?

- What Are the Six Stages of Kohlberg’s Theory of Moral Development?

- What Is Moral Development in a Child?

- What Is Moral Development, According to Kohlberg?

- How Many Levels of Moral Development Are There?

- Why Is Moral Development Significant in Early Childhood?

- What Factors Play Into Moral Development?

- What Is Moral Development in Adolescence?

- What Are the Characteristics of Moral Development?

- Why Is Kohlberg’s Theory of Moral Development Critical?

- What Characteristics Are Essential for Healthy Moral Development?

- How Do Parents Affect a Child’s Moral Development?

- What Is the Most Important Influence on a Child’s Moral Development?

- What Is the Role of the Teacher in Moral Development?

- Why Is Moral Development Significant?

- What Is Meant by Moral Development?

- Why Is Research on Moral Development Necessary?

- What Is the Study of Moral Development?

- What Factors Affect Moral Development?

- Which of the Following Researchers Studied Moral Development?

- How Did Kohlberg Research Moral Development?

- What Is Carol Gilligan’s Theory of Moral Development?

- How Did Piaget Study Moral Development?

- What Was Gilligan’s Main Criticism of Kohlberg’s Theory of Moral Development?

- What Is the Difference Between Kohlberg’s Theory of Moral Development and Gilligan’s Theory of Moral Evolution and Gender?

- Why Do Different Scholars Criticize Kohlberg’s Theory of Moral Development?

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2023, September 26). 99 Moral Development Essay Topic Ideas & Examples. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/moral-development-essay-topics/

"99 Moral Development Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." IvyPanda , 26 Sept. 2023, ivypanda.com/essays/topic/moral-development-essay-topics/.

IvyPanda . (2023) '99 Moral Development Essay Topic Ideas & Examples'. 26 September.

IvyPanda . 2023. "99 Moral Development Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." September 26, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/moral-development-essay-topics/.

1. IvyPanda . "99 Moral Development Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." September 26, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/moral-development-essay-topics/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "99 Moral Development Essay Topic Ideas & Examples." September 26, 2023. https://ivypanda.com/essays/topic/moral-development-essay-topics/.

- Organization Development Research Ideas

- Personality Development Ideas

- Professional Development Research Ideas

- Respect Essay Topics

- Ethics Ideas

- Lifespan Development Essay Titles

- Social Development Essay Topics

- Ethical Dilemma Titles

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Moral Theory

There is much disagreement about what, exactly, constitutes a moral theory. Some of that disagreement centers on the issue of demarcating the moral from other areas of practical normativity, such as the ethical and the aesthetic. Some disagreement centers on the issue of what a moral theory’s aims and functions are. In this entry, both questions will be addressed. However, this entry is about moral theories as theories , and is not a survey of specific theories, though specific theories will be used as examples.

1.1 Common-sense Morality

1.2 contrasts between morality and other normative domains, 2.1 the tasks of moral theory, 2.2 theory construction, 3. criteria, 4. decision procedures and practical deliberation, other internet resources, related entries, 1. morality.

When philosophers engage in moral theorizing, what is it that they are doing? Very broadly, they are attempting to provide a systematic account of morality. Thus, the object of moral theorizing is morality, and, further, morality as a normative system.

At the most minimal, morality is a set of norms and principles that govern our actions with respect to each other and which are taken to have a special kind of weight or authority (Strawson 1961). More fundamentally, we can also think of morality as consisting of moral reasons, either grounded in some more basic value, or, the other way around, grounding value (Raz 1999).

It is common, also, to hold that moral norms are universal in the sense that they apply to and bind everyone in similar circumstances. The principles expressing these norms are also thought to be general , rather than specific, in that they are formulable “without the use of what would be intuitively recognized as proper names, or rigged definite descriptions” (Rawls 1979, 131). They are also commonly held to be impartial , in holding everyone to count equally.

… Common-sense is… an exercise of the judgment unaided by any Art or system of rules : such an exercise as we must necessarily employ in numberless cases of daily occurrence ; in which, having no established principles to guide us … we must needs act on the best extemporaneous conjectures we can form. He who is eminently skillful in doing this, is said to possess a superior degree of Common-Sense. (Richard Whatley, Elements of Logic , 1851, xi–xii)

“Common-Sense Morality”, as the term is used here, refers to our pre-theoretic set of moral judgments or intuitions or principles. [ 1 ] When we engage in theory construction (see below) it is these common-sense intuitions that provide a touchstone to theory evaluation. Henry Sidgwick believed that the principles of Common-Sense Morality were important in helping us understand the “first” principle or principles of morality. [ 2 ] Indeed, some theory construction explicitly appeals to puzzles in common-sense morality that need resolution – and hence, need to be addressed theoretically.

Features of commons sense morality are determined by our normal reactions to cases which in turn suggest certain normative principles or insights. For example, one feature of common-sense morality that is often remarked upon is the self/other asymmetry in morality, which manifests itself in a variety of ways in our intuitive reactions. For example, many intuitively differentiate morality from prudence in holding that morality concerns our interactions with others, whereas prudence is concerned with the well-being of the individual, from that individual’s point of view.

Also, according to our common-sense intuitions we are allowed to pursue our own important projects even if such pursuit is not “optimific” from the impartial point of view (Slote 1985). It is also considered permissible, and even admirable, for an agent to sacrifice her own good for the sake of another even though that is not optimific. However, it is impermissible, and outrageous, for an agent to similarly sacrifice the well-being of another under the same circumstances. Samuel Scheffler argued for a view in which consequentialism is altered to include agent-centered prerogatives, that is, prerogatives to not act so as to maximize the good (Scheffler 1982).

Our reactions to certain cases also seem to indicate a common-sense commitment to the moral significance of the distinction between intention and foresight, doing versus allowing, as well as the view that distance between agent and patient is morally relevant (Kamm 2007).

Philosophers writing in empirical moral psychology have been working to identify other features of common-sense morality, such as how prior moral evaluations influence how we attribute moral responsibility for actions (Alicke et. al. 2011; Knobe 2003).