BRIEF RESEARCH REPORT article

How do critical thinking ability and critical thinking disposition relate to the mental health of university students.

- School of Education, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China

Theories of psychotherapy suggest that human mental problems associate with deficiencies in critical thinking. However, it currently remains unclear whether both critical thinking skill and critical thinking disposition relate to individual differences in mental health. This study explored whether and how the critical thinking ability and critical thinking disposition of university students associate with individual differences in mental health in considering impulsivity that has been revealed to be closely related to both critical thinking and mental health. Regression and structural equation modeling analyses based on a Chinese university student sample ( N = 314, 198 females, M age = 18.65) revealed that critical thinking skill and disposition explained a unique variance of mental health after controlling for impulsivity. Furthermore, the relationship between critical thinking and mental health was mediated by motor impulsivity (acting on the spur of the moment) and non-planning impulsivity (making decisions without careful forethought). These findings provide a preliminary account of how human critical thinking associate with mental health. Practically, developing mental health promotion programs for university students is suggested to pay special attention to cultivating their critical thinking dispositions and enhancing their control over impulsive behavior.

Introduction

Although there is no consistent definition of critical thinking (CT), it is usually described as “purposeful, self-regulatory judgment that results in interpretation, analysis, evaluation, and inference, as well as explanations of the evidential, conceptual, methodological, criteriological, or contextual considerations that judgment is based upon” ( Facione, 1990 , p. 2). This suggests that CT is a combination of skills and dispositions. The skill aspect mainly refers to higher-order cognitive skills such as inference, analysis, and evaluation, while the disposition aspect represents one's consistent motivation and willingness to use CT skills ( Dwyer, 2017 ). An increasing number of studies have indicated that CT plays crucial roles in the activities of university students such as their academic performance (e.g., Ghanizadeh, 2017 ; Ren et al., 2020 ), professional work (e.g., Barry et al., 2020 ), and even the ability to cope with life events (e.g., Butler et al., 2017 ). An area that has received less attention is how critical thinking relates to impulsivity and mental health. This study aimed to clarify the relationship between CT (which included both CT skill and CT disposition), impulsivity, and mental health among university students.

Relationship Between Critical Thinking and Mental Health

Associating critical thinking with mental health is not without reason, since theories of psychotherapy have long stressed a linkage between mental problems and dysfunctional thinking ( Gilbert, 2003 ; Gambrill, 2005 ; Cuijpers, 2019 ). Proponents of cognitive behavioral therapy suggest that the interpretation by people of a situation affects their emotional, behavioral, and physiological reactions. Those with mental problems are inclined to bias or heuristic thinking and are more likely to misinterpret neutral or even positive situations ( Hollon and Beck, 2013 ). Therefore, a main goal of cognitive behavioral therapy is to overcome biased thinking and change maladaptive beliefs via cognitive modification skills such as objective understanding of one's cognitive distortions, analyzing evidence for and against one's automatic thinking, or testing the effect of an alternative way of thinking. Achieving these therapeutic goals requires the involvement of critical thinking, such as the willingness and ability to critically analyze one's thoughts and evaluate evidence and arguments independently of one's prior beliefs. In addition to theoretical underpinnings, characteristics of university students also suggest a relationship between CT and mental health. University students are a risky population in terms of mental health. They face many normative transitions (e.g., social and romantic relationships, important exams, financial pressures), which are stressful ( Duffy et al., 2019 ). In particular, the risk increases when students experience academic failure ( Lee et al., 2008 ; Mamun et al., 2021 ). Hong et al. (2010) found that the stress in Chinese college students was primarily related to academic, personal, and negative life events. However, university students are also a population with many resources to work on. Critical thinking can be considered one of the important resources that students are able to use ( Stupple et al., 2017 ). Both CT skills and CT disposition are valuable qualities for college students to possess ( Facione, 1990 ). There is evidence showing that students with a higher level of CT are more successful in terms of academic performance ( Ghanizadeh, 2017 ; Ren et al., 2020 ), and that they are better at coping with stressful events ( Butler et al., 2017 ). This suggests that that students with higher CT are less likely to suffer from mental problems.

Empirical research has reported an association between CT and mental health among college students ( Suliman and Halabi, 2007 ; Kargar et al., 2013 ; Yoshinori and Marcus, 2013 ; Chen and Hwang, 2020 ; Ugwuozor et al., 2021 ). Most of these studies focused on the relationship between CT disposition and mental health. For example, Suliman and Halabi (2007) reported that the CT disposition of nursing students was positively correlated with their self-esteem, but was negatively correlated with their state anxiety. There is also a research study demonstrating that CT disposition influenced the intensity of worry in college students either by increasing their responsibility to continue thinking or by enhancing the detached awareness of negative thoughts ( Yoshinori and Marcus, 2013 ). Regarding the relationship between CT ability and mental health, although there has been no direct evidence, there were educational programs examining the effect of teaching CT skills on the mental health of adolescents ( Kargar et al., 2013 ). The results showed that teaching CT skills decreased somatic symptoms, anxiety, depression, and insomnia in adolescents. Another recent CT skill intervention also found a significant reduction in mental stress among university students, suggesting an association between CT skills and mental health ( Ugwuozor et al., 2021 ).

The above research provides preliminary evidence in favor of the relationship between CT and mental health, in line with theories of CT and psychotherapy. However, previous studies have focused solely on the disposition aspect of CT, and its link with mental health. The ability aspect of CT has been largely overlooked in examining its relationship with mental health. Moreover, although the link between CT and mental health has been reported, it remains unknown how CT (including skill and disposition) is associated with mental health.

Impulsivity as a Potential Mediator Between Critical Thinking and Mental Health

One important factor suggested by previous research in accounting for the relationship between CT and mental health is impulsivity. Impulsivity is recognized as a pattern of action without regard to consequences. Patton et al. (1995) proposed that impulsivity is a multi-faceted construct that consists of three behavioral factors, namely, non-planning impulsiveness, referring to making a decision without careful forethought; motor impulsiveness, referring to acting on the spur of the moment; and attentional impulsiveness, referring to one's inability to focus on the task at hand. Impulsivity is prominent in clinical problems associated with psychiatric disorders ( Fortgang et al., 2016 ). A number of mental problems are associated with increased impulsivity that is likely to aggravate clinical illnesses ( Leclair et al., 2020 ). Moreover, a lack of CT is correlated with poor impulse control ( Franco et al., 2017 ). Applications of CT may reduce impulsive behaviors caused by heuristic and biased thinking when one makes a decision ( West et al., 2008 ). For example, Gregory (1991) suggested that CT skills enhance the ability of children to anticipate the health or safety consequences of a decision. Given this, those with high levels of CT are expected to take a rigorous attitude about the consequences of actions and are less likely to engage in impulsive behaviors, which may place them at a low risk of suffering mental problems. To the knowledge of the authors, no study has empirically tested whether impulsivity accounts for the relationship between CT and mental health.

This study examined whether CT skill and disposition are related to the mental health of university students; and if yes, how the relationship works. First, we examined the simultaneous effects of CT ability and CT disposition on mental health. Second, we further tested whether impulsivity mediated the effects of CT on mental health. To achieve the goals, we collected data on CT ability, CT disposition, mental health, and impulsivity from a sample of university students. The results are expected to shed light on the mechanism of the association between CT and mental health.

Participants and Procedure

A total of 314 university students (116 men) with an average age of 18.65 years ( SD = 0.67) participated in this study. They were recruited by advertisements from a local university in central China and majoring in statistics and mathematical finance. The study protocol was approved by the Human Subjects Review Committee of the Huazhong University of Science and Technology. Each participant signed a written informed consent describing the study purpose, procedure, and right of free. All the measures were administered in a computer room. The participants were tested in groups of 20–30 by two research assistants. The researchers and research assistants had no formal connections with the participants. The testing included two sections with an interval of 10 min, so that the participants had an opportunity to take a break. In the first section, the participants completed the syllogistic reasoning problems with belief bias (SRPBB), the Chinese version of the California Critical Thinking Skills Test (CCSTS-CV), and the Chinese Critical Thinking Disposition Inventory (CCTDI), respectively. In the second session, they completed the Barrett Impulsivity Scale (BIS-11), Depression Anxiety Stress Scale-21 (DASS-21), and University Personality Inventory (UPI) in the given order.

Measures of Critical Thinking Ability

The Chinese version of the California Critical Thinking Skills Test was employed to measure CT skills ( Lin, 2018 ). The CCTST is currently the most cited tool for measuring CT skills and includes analysis, assessment, deduction, inductive reasoning, and inference reasoning. The Chinese version included 34 multiple choice items. The dependent variable was the number of correctly answered items. The internal consistency (Cronbach's α) of the CCTST is 0.56 ( Jacobs, 1995 ). The test–retest reliability of CCTST-CV is 0.63 ( p < 0.01) ( Luo and Yang, 2002 ), and correlations between scores of the subscales and the total score are larger than 0.5 ( Lin, 2018 ), supporting the construct validity of the scale. In this study among the university students, the internal consistency (Cronbach's α) of the CCTST-CV was 0.5.

The second critical thinking test employed in this study was adapted from the belief bias paradigm ( Li et al., 2021 ). This task paradigm measures the ability to evaluate evidence and arguments independently of one's prior beliefs ( West et al., 2008 ), which is a strongly emphasized skill in CT literature. The current test included 20 syllogistic reasoning problems in which the logical conclusion was inconsistent with one's prior knowledge (e.g., “Premise 1: All fruits are sweet. Premise 2: Bananas are not sweet. Conclusion: Bananas are not fruits.” valid conclusion). In addition, four non-conflict items were included as the neutral condition in order to avoid a habitual response from the participants. They were instructed to suppose that all the premises are true and to decide whether the conclusion logically follows from the given premises. The measure showed good internal consistency (Cronbach's α = 0.83) in a Chinese sample ( Li et al., 2021 ). In this study, the internal consistency (Cronbach's α) of the SRPBB was 0.94.

Measures of Critical Thinking Disposition

The Chinese Critical Thinking Disposition Inventory was employed to measure CT disposition ( Peng et al., 2004 ). This scale has been developed in line with the conceptual framework of the California critical thinking disposition inventory. We measured five CT dispositions: truth-seeking (one's objectivity with findings even if this requires changing one's preconceived opinions, e.g., a person inclined toward being truth-seeking might disagree with “I believe what I want to believe.”), inquisitiveness (one's intellectual curiosity. e.g., “No matter what the topic, I am eager to know more about it”), analyticity (the tendency to use reasoning and evidence to solve problems, e.g., “It bothers me when people rely on weak arguments to defend good ideas”), systematically (the disposition of being organized and orderly in inquiry, e.g., “I always focus on the question before I attempt to answer it”), and CT self-confidence (the trust one places in one's own reasoning processes, e.g., “I appreciate my ability to think precisely”). Each disposition aspect contained 10 items, which the participants rated on a 6-point Likert-type scale. This measure has shown high internal consistency (overall Cronbach's α = 0.9) ( Peng et al., 2004 ). In this study, the CCTDI scale was assessed at Cronbach's α = 0.89, indicating good reliability.

Measure of Impulsivity

The well-known Barrett Impulsivity Scale ( Patton et al., 1995 ) was employed to assess three facets of impulsivity: non-planning impulsivity (e.g., “I plan tasks carefully”); motor impulsivity (e.g., “I act on the spur of the moment”); attentional impulsivity (e.g., “I concentrate easily”). The scale includes 30 statements, and each statement is rated on a 5-point scale. The subscales of non-planning impulsivity and attentional impulsivity were reversely scored. The BIS-11 has good internal consistency (Cronbach's α = 0.81, Velotti et al., 2016 ). This study showed that the Cronbach's α of the BIS-11 was 0.83.

Measures of Mental Health

The Depression Anxiety Stress Scale-21 was used to assess mental health problems such as depression (e.g., “I feel that life is meaningless”), anxiety (e.g., “I find myself getting agitated”), and stress (e.g., “I find it difficult to relax”). Each dimension included seven items, which the participants were asked to rate on a 4-point scale. The Chinese version of the DASS-21 has displayed a satisfactory factor structure and internal consistency (Cronbach's α = 0.92, Wang et al., 2016 ). In this study, the internal consistency (Cronbach's α) of the DASS-21 was 0.94.

The University Personality Inventory that has been commonly used to screen for mental problems of college students ( Yoshida et al., 1998 ) was also used for measuring mental health. The 56 symptom-items assessed whether an individual has experienced the described symptom during the past year (e.g., “a lack of interest in anything”). The UPI showed good internal consistency (Cronbach's α = 0.92) in a Chinese sample ( Zhang et al., 2015 ). This study showed that the Cronbach's α of the UPI was 0.85.

Statistical Analyses

We first performed analyses to detect outliers. Any observation exceeding three standard deviations from the means was replaced with a value that was three standard deviations. This procedure affected no more than 5‰ of observations. Hierarchical regression analysis was conducted to determine the extent to which facets of critical thinking were related to mental health. In addition, structural equation modeling with Amos 22.0 was performed to assess the latent relationship between CT, impulsivity, and mental health.

Descriptive Statistics and Bivariate Correlations

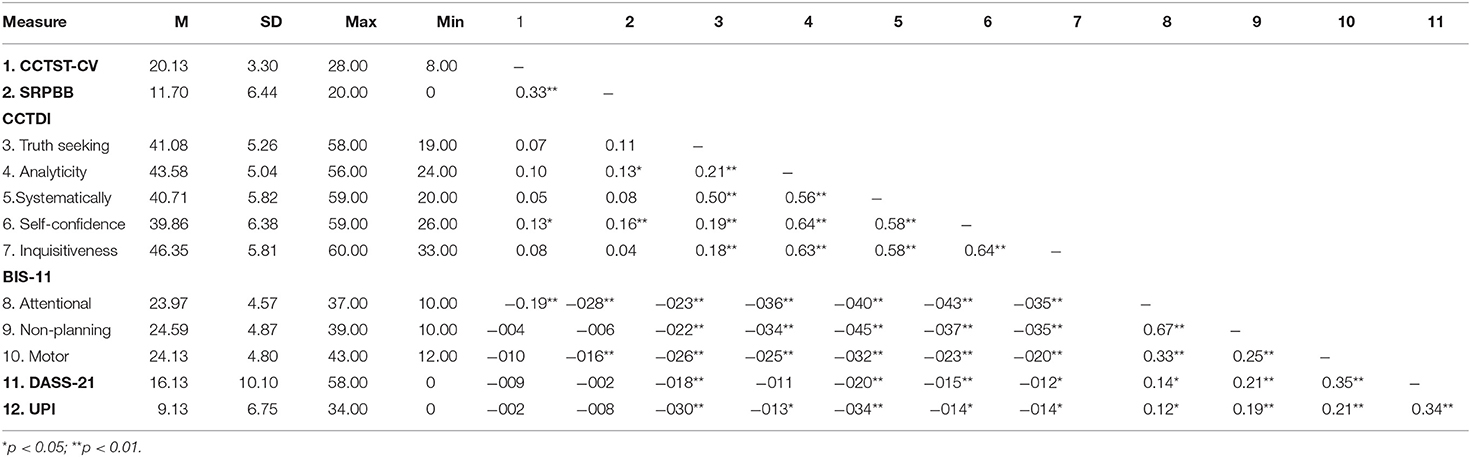

Table 1 presents descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations of all the variables. CT disposition such as truth-seeking, systematicity, self-confidence, and inquisitiveness was significantly correlated with DASS-21 and UPI, but neither CCTST-CV nor SRPBB was related to DASS-21 and UPI. Subscales of BIS-11 were positively correlated with DASS-21 and UPI, but were negatively associated with CT dispositions.

Table 1 . Descriptive results and correlations between all measured variables ( N = 314).

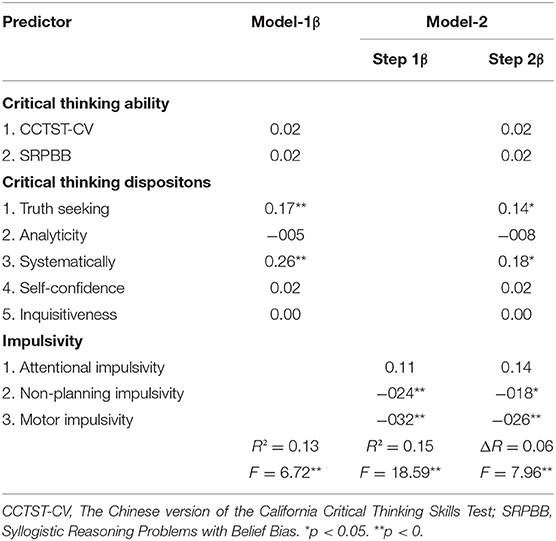

Regression Analyses

Hierarchical regression analyses were conducted to examine the effects of CT skill and disposition on mental health. Before conducting the analyses, scores in DASS-21 and UPI were reversed so that high scores reflected high levels of mental health. Table 2 presents the results of hierarchical regression. In model 1, the sum of the Z-score of DASS-21 and UPI served as the dependent variable. Scores in the CT ability tests and scores in the five dimensions of CCTDI served as predictors. CT skill and disposition explained 13% of the variance in mental health. CT skills did not significantly predict mental health. Two dimensions of dispositions (truth seeking and systematicity) exerted significantly positive effects on mental health. Model 2 examined whether CT predicted mental health after controlling for impulsivity. The model containing only impulsivity scores (see model-2 step 1 in Table 2 ) explained 15% of the variance in mental health. Non-planning impulsivity and motor impulsivity showed significantly negative effects on mental health. The CT variables on the second step explained a significantly unique variance (6%) of CT (see model-2 step 2). This suggests that CT skill and disposition together explained the unique variance in mental health after controlling for impulsivity. 1

Table 2 . Hierarchical regression models predicting mental health from critical thinking skills, critical thinking dispositions, and impulsivity ( N = 314).

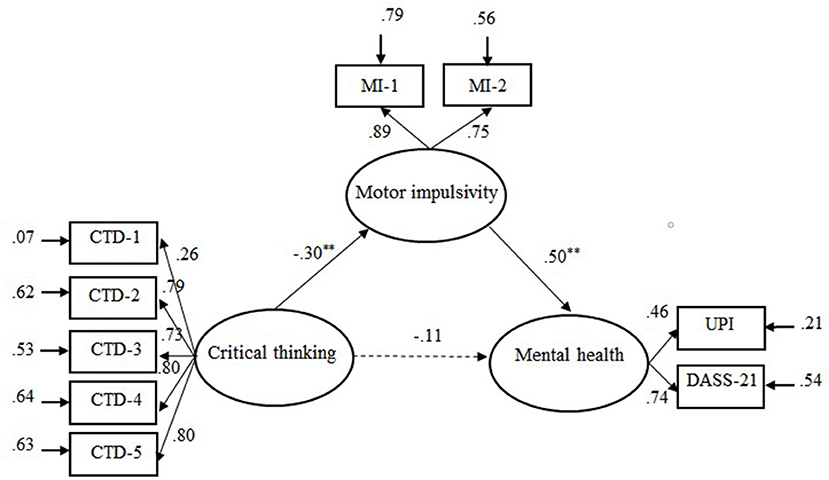

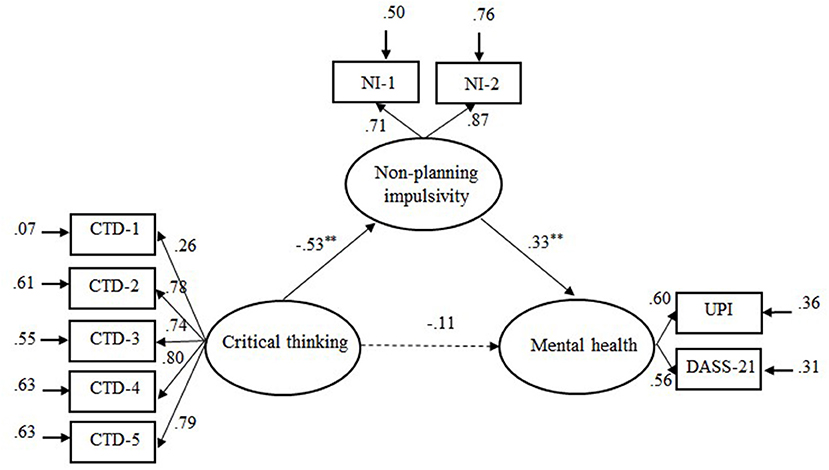

Structural equation modeling was performed to examine whether impulsivity mediated the relationship between CT disposition (CT ability was not included since it did not significantly predict mental health) and mental health. Since the regression results showed that only motor impulsivity and non-planning impulsivity significantly predicted mental health, we examined two mediation models with either motor impulsivity or non-planning impulsivity as the hypothesized mediator. The item scores in the motor impulsivity subscale were randomly divided into two indicators of motor impulsivity, as were the scores in the non-planning subscale. Scores of DASS-21 and UPI served as indicators of mental health and dimensions of CCTDI as indicators of CT disposition. In addition, a bootstrapping procedure with 5,000 resamples was established to test for direct and indirect effects. Amos 22.0 was used for the above analyses.

The mediation model that included motor impulsivity (see Figure 1 ) showed an acceptable fit, χ ( 23 ) 2 = 64.71, RMSEA = 0.076, CFI = 0.96, GFI = 0.96, NNFI = 0.93, SRMR = 0.073. Mediation analyses indicated that the 95% boot confidence intervals of the indirect effect and the direct effect were (0.07, 0.26) and (−0.08, 0.32), respectively. As Hayes (2009) indicates, an effect is significant if zero is not between the lower and upper bounds in the 95% confidence interval. Accordingly, the indirect effect between CT disposition and mental health was significant, while the direct effect was not significant. Thus, motor impulsivity completely mediated the relationship between CT disposition and mental health.

Figure 1 . Illustration of the mediation model: Motor impulsivity as mediator variable between critical thinking dispositions and mental health. CTD-l = Truth seeking; CTD-2 = Analyticity; CTD-3 = Systematically; CTD-4 = Self-confidence; CTD-5 = Inquisitiveness. MI-I and MI-2 were sub-scores of motor impulsivity. Solid line represents significant links and dotted line non-significant links. ** p < 0.01.

The mediation model, which included non-planning impulsivity (see Figure 2 ), also showed an acceptable fit to the data, χ ( 23 ) 2 = 52.75, RMSEA = 0.064, CFI = 0.97, GFI = 0.97, NNFI = 0.95, SRMR = 0.06. The 95% boot confidence intervals of the indirect effect and the direct effect were (0.05, 0.33) and (−0.04, 0.38), respectively, indicating that non-planning impulsivity completely mediated the relationship between CT disposition and mental health.

Figure 2 . Illustration of the mediation model: Non-planning impulsivity asmediator variable between critical thinking dispositions and mental health. CTD-l = Truth seeking; CTD-2 = Analyticity; CTD-3 = Systematically; CTD-4 = Self-confidence; CTD-5 = Inquisitiveness. NI-I and NI-2 were sub-scores of Non-planning impulsivity. Solid line represents significant links and dotted line non-significant links. ** p < 0.01.

This study examined how critical thinking skill and disposition are related to mental health. Theories of psychotherapy suggest that human mental problems are in part due to a lack of CT. However, empirical evidence for the hypothesized relationship between CT and mental health is relatively scarce. This study explored whether and how CT ability and disposition are associated with mental health. The results, based on a university student sample, indicated that CT skill and disposition explained a unique variance in mental health. Furthermore, the effect of CT disposition on mental health was mediated by motor impulsivity and non-planning impulsivity. The finding that CT exerted a significant effect on mental health was in accordance with previous studies reporting negative correlations between CT disposition and mental disorders such as anxiety ( Suliman and Halabi, 2007 ). One reason lies in the assumption that CT disposition is usually referred to as personality traits or habits of mind that are a remarkable predictor of mental health (e.g., Benzi et al., 2019 ). This study further found that of the five CT dispositions, only truth-seeking and systematicity were associated with individual differences in mental health. This was not surprising, since the truth-seeking items mainly assess one's inclination to crave for the best knowledge in a given context and to reflect more about additional facts, reasons, or opinions, even if this requires changing one's mind about certain issues. The systematicity items target one's disposition to approach problems in an orderly and focused way. Individuals with high levels of truth-seeking and systematicity are more likely to adopt a comprehensive, reflective, and controlled way of thinking, which is what cognitive therapy aims to achieve by shifting from an automatic mode of processing to a more reflective and controlled mode.

Another important finding was that motor impulsivity and non-planning impulsivity mediated the effect of CT disposition on mental health. The reason may be that people lacking CT have less willingness to enter into a systematically analyzing process or deliberative decision-making process, resulting in more frequently rash behaviors or unplanned actions without regard for consequences ( Billieux et al., 2010 ; Franco et al., 2017 ). Such responses can potentially have tangible negative consequences (e.g., conflict, aggression, addiction) that may lead to social maladjustment that is regarded as a symptom of mental illness. On the contrary, critical thinkers have a sense of deliberativeness and consider alternate consequences before acting, and this thinking-before-acting mode would logically lead to a decrease in impulsivity, which then decreases the likelihood of problematic behaviors and negative moods.

It should be noted that although the raw correlation between attentional impulsivity and mental health was significant, regression analyses with the three dimensions of impulsivity as predictors showed that attentional impulsivity no longer exerted a significant effect on mental effect after controlling for the other impulsivity dimensions. The insignificance of this effect suggests that the significant raw correlation between attentional impulsivity and mental health was due to the variance it shared with the other impulsivity dimensions (especially with the non-planning dimension, which showed a moderately high correlation with attentional impulsivity, r = 0.67).

Some limitations of this study need to be mentioned. First, the sample involved in this study is considered as a limited sample pool, since all the participants are university students enrolled in statistics and mathematical finance, limiting the generalization of the findings. Future studies are recommended to recruit a more representative sample of university students. A study on generalization to a clinical sample is also recommended. Second, as this study was cross-sectional in nature, caution must be taken in interpreting the findings as causal. Further studies using longitudinal, controlled designs are needed to assess the effectiveness of CT intervention on mental health.

In spite of the limitations mentioned above, the findings of this study have some implications for research and practice intervention. The result that CT contributed to individual differences in mental health provides empirical support for the theory of cognitive behavioral therapy, which focuses on changing irrational thoughts. The mediating role of impulsivity between CT and mental health gives a preliminary account of the mechanism of how CT is associated with mental health. Practically, although there is evidence that CT disposition of students improves because of teaching or training interventions (e.g., Profetto-Mcgrath, 2005 ; Sanja and Krstivoje, 2015 ; Chan, 2019 ), the results showing that two CT disposition dimensions, namely, truth-seeking and systematicity, are related to mental health further suggest that special attention should be paid to cultivating these specific CT dispositions so as to enhance the control of students over impulsive behaviors in their mental health promotions.

Conclusions

This study revealed that two CT dispositions, truth-seeking and systematicity, were associated with individual differences in mental health. Furthermore, the relationship between critical thinking and mental health was mediated by motor impulsivity and non-planning impulsivity. These findings provide a preliminary account of how human critical thinking is associated with mental health. Practically, developing mental health promotion programs for university students is suggested to pay special attention to cultivating their critical thinking dispositions (especially truth-seeking and systematicity) and enhancing the control of individuals over impulsive behaviors.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by HUST Critical Thinking Research Center (Grant No. 2018CT012). The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

XR designed the study and revised the manuscript. ZL collected data and wrote the manuscript. SL assisted in analyzing the data. SS assisted in re-drafting and editing the manuscript. All the authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This work was supported by the Social Science Foundation of China (grant number: BBA200034).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. ^ We re-analyzed the data by controlling for age and gender of the participants in the regression analyses. The results were virtually the same as those reported in the study.

Barry, A., Parvan, K., Sarbakhsh, P., Safa, B., and Allahbakhshian, A. (2020). Critical thinking in nursing students and its relationship with professional self-concept and relevant factors. Res. Dev. Med. Educ. 9, 7–7. doi: 10.34172/rdme.2020.007

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Benzi, I. M. A., Emanuele, P., Rossella, D. P., Clarkin, J. F., and Fabio, M. (2019). Maladaptive personality traits and psychological distress in adolescence: the moderating role of personality functioning. Pers. Indiv. Diff. 140, 33–40. doi: 10.1016/j.paid.2018.06.026

Billieux, J., Gay, P., Rochat, L., and Van der Linden, M. (2010). The role of urgency and its underlying psychological mechanisms in problematic behaviours. Behav. Res. Ther. 48, 1085–1096. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2010.07.008

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Butler, H. A., Pentoney, C., and Bong, M. P. (2017). Predicting real-world outcomes: Critical thinking ability is a better predictor of life decisions than intelligence. Think. Skills Creat. 25, 38–46. doi: 10.1016/j.tsc.2017.06.005

Chan, C. (2019). Using digital storytelling to facilitate critical thinking disposition in youth civic engagement: a randomized control trial. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 107:104522. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.104522

Chen, M. R. A., and Hwang, G. J. (2020). Effects of a concept mapping-based flipped learning approach on EFL students' English speaking performance, critical thinking awareness and speaking anxiety. Br. J. Educ. Technol. 51, 817–834. doi: 10.1111/bjet.12887

Cuijpers, P. (2019). Targets and outcomes of psychotherapies for mental disorders: anoverview. World Psychiatry. 18, 276–285. doi: 10.1002/wps.20661

Duffy, M. E., Twenge, J. M., and Joiner, T. E. (2019). Trends in mood and anxiety symptoms and suicide-related outcomes among u.s. undergraduates, 2007–2018: evidence from two national surveys. J. Adolesc. Health. 65, 590–598. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2019.04.033

Dwyer, C. P. (2017). Critical Thinking: Conceptual Perspectives and Practical Guidelines . Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Google Scholar

Facione, P. A. (1990). Critical Thinking: Astatement of Expert Consensus for Purposes of Educational Assessment and Instruction . Millibrae, CA: The California Academic Press.

Fortgang, R. G., Hultman, C. M., van Erp, T. G. M., and Cannon, T. D. (2016). Multidimensional assessment of impulsivity in schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder: testing for shared endophenotypes. Psychol. Med. 46, 1497–1507. doi: 10.1017/S0033291716000131

Franco, A. R., Costa, P. S., Butler, H. A., and Almeida, L. S. (2017). Assessment of undergraduates' real-world outcomes of critical thinking in everyday situations. Psychol. Rep. 120, 707–720. doi: 10.1177/0033294117701906

Gambrill, E. (2005). “Critical thinking, evidence-based practice, and mental health,” in Mental Disorders in the Social Environment: Critical Perspectives , ed S. A. Kirk (New York, NY: Columbia University Press), 247–269.

PubMed Abstract | Google Scholar

Ghanizadeh, A. (2017). The interplay between reflective thinking, critical thinking, self-monitoring, and academic achievement in higher education. Higher Educ. 74. 101–114. doi: 10.1007/s10734-016-0031-y

Gilbert, T. (2003). Some reflections on critical thinking and mental health. Teach. Phil. 24, 333–339. doi: 10.5840/teachphil200326446

Gregory, R. (1991). Critical thinking for environmental health risk education. Health Educ. Q. 18, 273–284. doi: 10.1177/109019819101800302

Hayes, A. F. (2009). Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the newmillennium. Commun. Monogr. 76, 408–420. doi: 10.1080/03637750903310360

Hollon, S. D., and Beck, A. T. (2013). “Cognitive and cognitive-behavioral therapies,” in Bergin and Garfield's Handbook of Psychotherapy and Behavior Change, Vol. 6 . ed M. J. Lambert (Hoboken, NJ: Wiley), 393–442.

Hong, L., Lin, C. D., Bray, M. A., and Kehle, T. J. (2010). The measurement of stressful events in chinese college students. Psychol. Sch. 42, 315–323. doi: 10.1002/pits.20082

CrossRef Full Text

Jacobs, S. S. (1995). Technical characteristics and some correlates of the california critical thinking skills test, forms a and b. Res. Higher Educ. 36, 89–108.

Kargar, F. R., Ajilchi, B., Goreyshi, M. K., and Noohi, S. (2013). Effect of creative and critical thinking skills teaching on identity styles and general health in adolescents. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 84, 464–469. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.06.585

Leclair, M. C., Lemieux, A. J., Roy, L., Martin, M. S., Latimer, E. A., and Crocker, A. G. (2020). Pathways to recovery among homeless people with mental illness: Is impulsiveness getting in the way? Can. J. Psychiatry. 65, 473–483. doi: 10.1177/0706743719885477

Lee, H. S., Kim, S., Choi, I., and Lee, K. U. (2008). Prevalence and risk factors associated with suicide ideation and attempts in korean college students. Psychiatry Investig. 5, 86–93. doi: 10.4306/pi.2008.5.2.86

Li, S., Ren, X., Schweizer, K., Brinthaupt, T. M., and Wang, T. (2021). Executive functions as predictors of critical thinking: behavioral and neural evidence. Learn. Instruct. 71:101376. doi: 10.1016/j.learninstruc.2020.101376

Lin, Y. (2018). Developing Critical Thinking in EFL Classes: An Infusion Approach . Singapore: Springer Publications.

Luo, Q. X., and Yang, X. H. (2002). Revising on Chinese version of California critical thinkingskillstest. Psychol. Sci. (Chinese). 25, 740–741.

Mamun, M. A., Misti, J. M., Hosen, I., and Mamun, F. A. (2021). Suicidal behaviors and university entrance test-related factors: a bangladeshi exploratory study. Persp. Psychiatric Care. 4, 1–10. doi: 10.1111/ppc.12783

Patton, J. H., Stanford, M. S., and Barratt, E. S. (1995). Factor structure of the Barratt impulsiveness scale. J Clin. Psychol. 51, 768–774. doi: 10.1002/1097-4679(199511)51:63.0.CO;2-1

Peng, M. C., Wang, G. C., Chen, J. L., Chen, M. H., Bai, H. H., Li, S. G., et al. (2004). Validity and reliability of the Chinese critical thinking disposition inventory. J. Nurs. China (Zhong Hua Hu Li Za Zhi). 39, 644–647.

Profetto-Mcgrath, J. (2005). Critical thinking and evidence-based practice. J. Prof. Nurs. 21, 364–371. doi: 10.1016/j.profnurs.2005.10.002

Ren, X., Tong, Y., Peng, P., and Wang, T. (2020). Critical thinking predicts academic performance beyond general cognitive ability: evidence from adults and children. Intelligence 82:101487. doi: 10.1016/j.intell.2020.101487

Sanja, M., and Krstivoje, S. (2015). Developing critical thinking in elementary mathematics education through a suitable selection of content and overall student performance. Proc. Soc. Behav. Sci. 180, 653–659. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.02.174

Stupple, E., Maratos, F. A., Elander, J., Hunt, T. E., and Aubeeluck, A. V. (2017). Development of the critical thinking toolkit (critt): a measure of student attitudes and beliefs about critical thinking. Think. Skills Creat. 23, 91–100. doi: 10.1016/j.tsc.2016.11.007

Suliman, W. A., and Halabi, J. (2007). Critical thinking, self-esteem, and state anxiety of nursing students. Nurse Educ. Today. 27, 162–168. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2006.04.008

Ugwuozor, F. O., Otu, M. S., and Mbaji, I. N. (2021). Critical thinking intervention for stress reduction among undergraduates in the Nigerian Universities. Medicine 100:25030. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000025030

Velotti, P., Garofalo, C., Petrocchi, C., Cavallo, F., Popolo, R., and Dimaggio, G. (2016). Alexithymia, emotion dysregulation, impulsivity and aggression: a multiple mediation model. Psychiatry Res. 237, 296–303. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.01.025

Wang, K., Shi, H. S., Geng, F. L., Zou, L. Q., Tan, S. P., Wang, Y., et al. (2016). Cross-cultural validation of the depression anxiety stress scale−21 in China. Psychol. Assess. 28:e88. doi: 10.1037/pas0000207

West, R. F., Toplak, M. E., and Stanovich, K. E. (2008). Heuristics and biases as measures of critical thinking: associations with cognitive ability and thinking dispositions. J. Educ. Psychol. 100, 930–941. doi: 10.1037/a0012842

Yoshida, T., Ichikawa, T., Ishikawa, T., and Hori, M. (1998). Mental health of visually and hearing impaired students from the viewpoint of the University Personality Inventory. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 52, 413–418.

Yoshinori, S., and Marcus, G. (2013). The dual effects of critical thinking disposition on worry. PLoS ONE 8:e79714. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.007971

Zhang, J., Lanza, S., Zhang, M., and Su, B. (2015). Structure of the University personality inventory for chinese college students. Psychol. Rep. 116, 821–839. doi: 10.2466/08.02.PR0.116k26w3

Keywords: mental health, critical thinking ability, critical thinking disposition, impulsivity, depression

Citation: Liu Z, Li S, Shang S and Ren X (2021) How Do Critical Thinking Ability and Critical Thinking Disposition Relate to the Mental Health of University Students? Front. Psychol. 12:704229. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.704229

Received: 04 May 2021; Accepted: 21 July 2021; Published: 19 August 2021.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2021 Liu, Li, Shang and Ren. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xuezhu Ren, renxz@hust.edu.cn

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

- First Appointment Online Booking

- One To One Therapy

- Specialist in PTSD & Trauma Online Counselling

- Executive Coaching & Management Therapy

- Professional Patient Referral Therapy Services

- Bipolar Disorder Therapy

- Anger Management Therapy

- Anxiety Therapy

- Confidence Therapy

- Depression Therapy

- Marriage Therapy

- Panic Therapy

- Sex Therapy

- Trauma / PTSD Therapy

- Full List of Therapy Services

- How To Stress Less.

- How To Change Your Life.

- Hypnotherapy Audiobooks

- Meditation Audiobooks

- Audiobooks With Audible

- Audiobooks With iTunes

- Erectile Dysfunction Solutions

- Premature Ejaculation Solution

- Weight Loss Support

- Supplements For The Brain

- Recommended Brands

- Recommended Reading

- Training & Workshops For Your Business

The Science Behind Critical Thinking and Its Role in Mental Health

In the journey towards understanding and improving mental health, one cannot overlook the influence of a powerful cognitive tool known as critical thinking..

Here we will delve into the science underpinning critical thinking and shed light on its role in bolstering mental health.

Exploring the Foundations of Critical Thinking

The term 'critical thinking' encompasses a broad set of cognitive skills and dispositions aimed at objective analysis and evaluation of information. It involves thinking in a clear, logical, and reflective manner to make reasoned judgements. Critical thinking is not merely being critical in the negative sense, but rather, it's about engaging with information critically - questioning, analysing, and evaluating - to reach a sound, unbiased conclusion.

The science behind critical thinking is rooted in various cognitive processes, including perception, memory, attention, and problem-solving. It involves the prefrontal cortex, the part of the brain associated with complex cognitive behaviour, decision-making, and social behaviour. A strong capacity for critical thinking implies that these cognitive processes and brain regions are functioning optimally.

Critical Thinking and Mental Health: The Connection

The relationship between critical thinking and mental health is more intertwined than it might initially appear. Many mental health issues can be traced back to negative or distorted thinking patterns. These unhelpful thinking styles can lead to emotional distress and behavioural problems. It's here that critical thinking comes into play, as it equips individuals with the ability to identify, analyse, and ultimately challenge these negative thought patterns.

The Interplay of Perception and Critical Thinking

Perception, the process of interpreting the information that we receive through our senses, plays a significant role in critical thinking. It shapes our understanding of the world around us and influences our reactions to various situations. However, perception can sometimes be biased or distorted, leading to misunderstandings or misconceptions.

Critical thinking allows us to scrutinise our perceptions and question their accuracy. It encourages us to seek evidence and consider alternative perspectives, leading to a more accurate and comprehensive understanding of our experiences. This process can have a profound impact on our mental health, as it helps to challenge distorted perceptions that can fuel negative emotions or unhealthy behaviours.

Memory's Role in Critical Thinking

Memory, another key cognitive process, also intersects with critical thinking. Our memories of past experiences can shape our current thoughts, feelings, and behaviours. However, memories are not always accurate representations of reality. They can be influenced by our current mood, biases, and beliefs, leading to distorted recollections.

Critical thinking can help us evaluate our memories objectively. It prompts us to question the accuracy of our recollections and consider the influence of external factors. This reflective approach can prevent us from basing our beliefs or behaviours on distorted memories, thereby enhancing our mental health.

Attention and Its Influence on Critical Thinking

Attention, the cognitive process of selectively concentrating on one aspect while ignoring others, is crucial for critical thinking. It enables us to focus on relevant information and ignore irrelevant distractions. However, attention can be biased towards negative information, especially in individuals with mental health issues such as anxiety or depression.

Critical thinking skills can aid in managing attentional biases. It involves questioning why we are focusing on certain aspects and ignoring others, considering the impact of this focus, and making a conscious effort to direct our attention in a more balanced manner. This approach can reduce negative bias, improve emotional well-being, and enhance overall mental health.

Problem-Solving: A Crucial Component of Critical Thinking

Problem-solving is an integral part of critical thinking. It involves identifying problems, generating potential solutions, and evaluating these solutions to make an informed decision. Individuals with strong problem-solving skills are often good critical thinkers, as they can analyse situations objectively, consider various solutions, and make reasoned decisions based on evidence. In the context of mental health, problem-solving skills can help manage stress, navigate life's challenges, and improve overall well-being.

Cognitive Biases and Critical Thinking

Cognitive biases, systematic errors in thinking that influence our judgements and decisions, can impede critical thinking. They can lead to distorted perceptions, irrational beliefs, and poor decision-making, which can negatively impact mental health. Common cognitive biases include confirmation bias, where we focus on information that confirms our pre-existing beliefs, and negativity bias, where we pay more attention to negative information.

Critical thinking can help us recognise and overcome these cognitive biases. It encourages us to question our biases, seek diverse perspectives, and make decisions based on objective evidence rather than biased perceptions. By mitigating the impact of cognitive biases, critical thinking can promote healthier thought patterns, better decision-making, and improved mental health.

The Impact of Critical Thinking on Emotional Intelligence

Emotional intelligence, the ability to understand, use, and manage our own emotions in positive ways, can be enhanced through critical thinking. By critically analysing our emotional responses, we can gain insights into our emotional patterns, understand the triggers for certain emotions, and develop effective strategies to manage these emotions. This understanding can lead to improved emotional regulation, better interpersonal relationships, and enhanced mental health.

Critical Thinking and Resilience

Critical thinking also plays a significant role in building resilience, the ability to bounce back from adversity. Resilient individuals use critical thinking to understand the nature of the adversity, explore various coping strategies, and make informed decisions to overcome the challenge. This ability not only helps manage the immediate adversity but also fosters mental strength, which can safeguard against future challenges.

In conclusion, the science behind critical thinking and its role in mental health is a fascinating and integral area of exploration. By enhancing our cognitive processes, helping us navigate our emotions, and bolstering our resilience, critical thinking serves as a powerful tool for mental health.

At times, life can be overwhelming and leave us feeling lost, anxious, or depressed.

Counselling can provide the support and guidance needed to navigate difficult times and achieve mental well-being. We offer a safe and confidential space to explore your thoughts, feelings, and concerns. We believe that everyone deserves access to quality mental health care, and we strive to provide an inclusive and non-judgmental environment for all.

If you are struggling with mental health issues or feeling overwhelmed, we invite you to reach out to us for support. We are here to listen, guide, and empower you towards a healthier and happier life. Don't let mental health challenges hold you back from living your best life. Contact us today to schedule an appointment and take the first step towards better mental health.

How Do Critical Thinking Ability and Critical Thinking Disposition Relate to the Mental Health of University Students?

Affiliation.

- 1 School of Education, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China.

- PMID: 34489809

- PMCID: PMC8416899

- DOI: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.704229

Theories of psychotherapy suggest that human mental problems associate with deficiencies in critical thinking. However, it currently remains unclear whether both critical thinking skill and critical thinking disposition relate to individual differences in mental health. This study explored whether and how the critical thinking ability and critical thinking disposition of university students associate with individual differences in mental health in considering impulsivity that has been revealed to be closely related to both critical thinking and mental health. Regression and structural equation modeling analyses based on a Chinese university student sample ( N = 314, 198 females, M age = 18.65) revealed that critical thinking skill and disposition explained a unique variance of mental health after controlling for impulsivity. Furthermore, the relationship between critical thinking and mental health was mediated by motor impulsivity (acting on the spur of the moment) and non-planning impulsivity (making decisions without careful forethought). These findings provide a preliminary account of how human critical thinking associate with mental health. Practically, developing mental health promotion programs for university students is suggested to pay special attention to cultivating their critical thinking dispositions and enhancing their control over impulsive behavior.

Keywords: critical thinking ability; critical thinking disposition; depression; impulsivity; mental health.

Copyright © 2021 Liu, Li, Shang and Ren.

How do mental disorders impact our decision-making?

For some people suffering from illnesses such as schizophrenia and substance use disorder – previously referred to as “ substance abuse ” – making the right choices can be extremely difficult.

In fact, many mental illnesses feature problems with cognition (thinking and comprehension), including depression and bipolar disorder. Decision-making ability varies in healthy people, too, sometimes as a consequence of differences in genetics .

What’s happening in the brains of these people that puts them on unequal footing to the rest of us?

Even simple decisions are complex

It’s important to note in day-to-day situations, there’s often no distinctly “right” or “wrong” choice to be made. However, some choices do result in healthier or more productive outcomes for us and those around us.

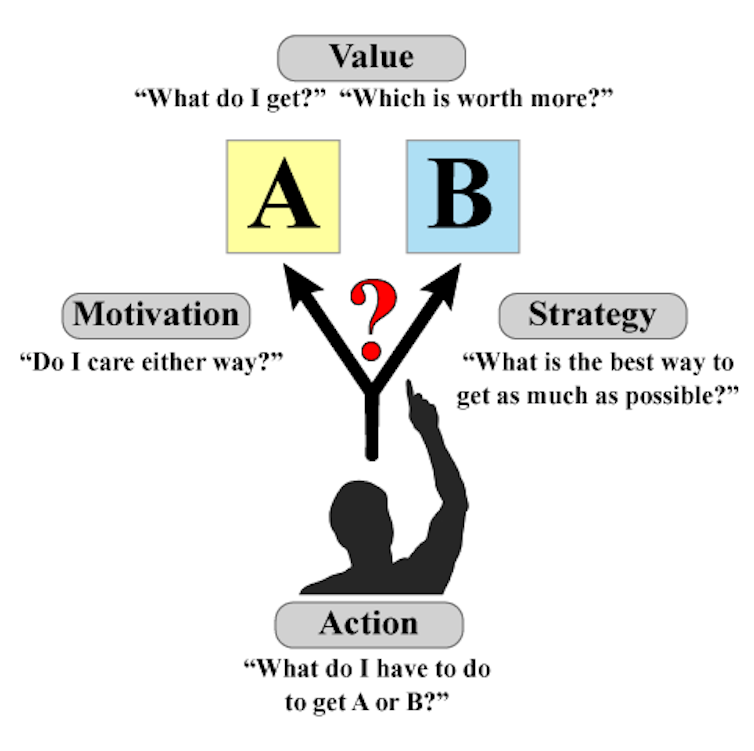

Our brains carry out a suite of complex processes when making decisions. And there are four important factors in each decision we make: value, motivation, action and strategy.

- Mapping health risks for people with mental disorders

- Researchers recognised for expanding knowledge of schizophrenia

- Research bears fruit for schizophrenia patients

When choosing between two options, say A and B, we first need to understand which choice will be more rewarding, or provide more value . Our personal motivation to attain this reward then acts to bias which option we choose, or whether we make a choice at all.

Understanding what action is required to obtain A, or B, is also important. Combining all this information, we try to understand which strategy will maximise our rewards. And this lets us improve our decision-making ability over time.

Connections interrupted by mental disorders

We refer to our personal history and past experiences to guide our future choices. But mental disorders often cause problems in the decision-making process.

Research shows people with schizophrenia can have trouble understanding the relationship between their actions and the outcomes . This means they might keep selecting A, even if they know it’s no longer as valuable as B.

They’re also more willing to adopt strategies based on less information, in other words “ jump to conclusions ”, about outcomes.

Substance use disorder, particularly with stimulants such as methamphetamine or cocaine, often leads to people getting stuck when certain outcomes change .

For example, if we reversed all the street lights so red meant “go” and green meant “stop” without telling anyone, most people would get an initial shock but would eventually alter their behaviour.

People with stimulant dependence, however, would take longer to learn to stop on the green light – even if they kept getting into car accidents. This is because excessive stimulant use impacts regions in the brain that are crucial to adapting to changing environments.

How the brain decodes each decision

The human brain contains multiple circuits (like pathways) and chemical messengers called “neurotransmitters”. These are responsible for guiding the processes discussed above.

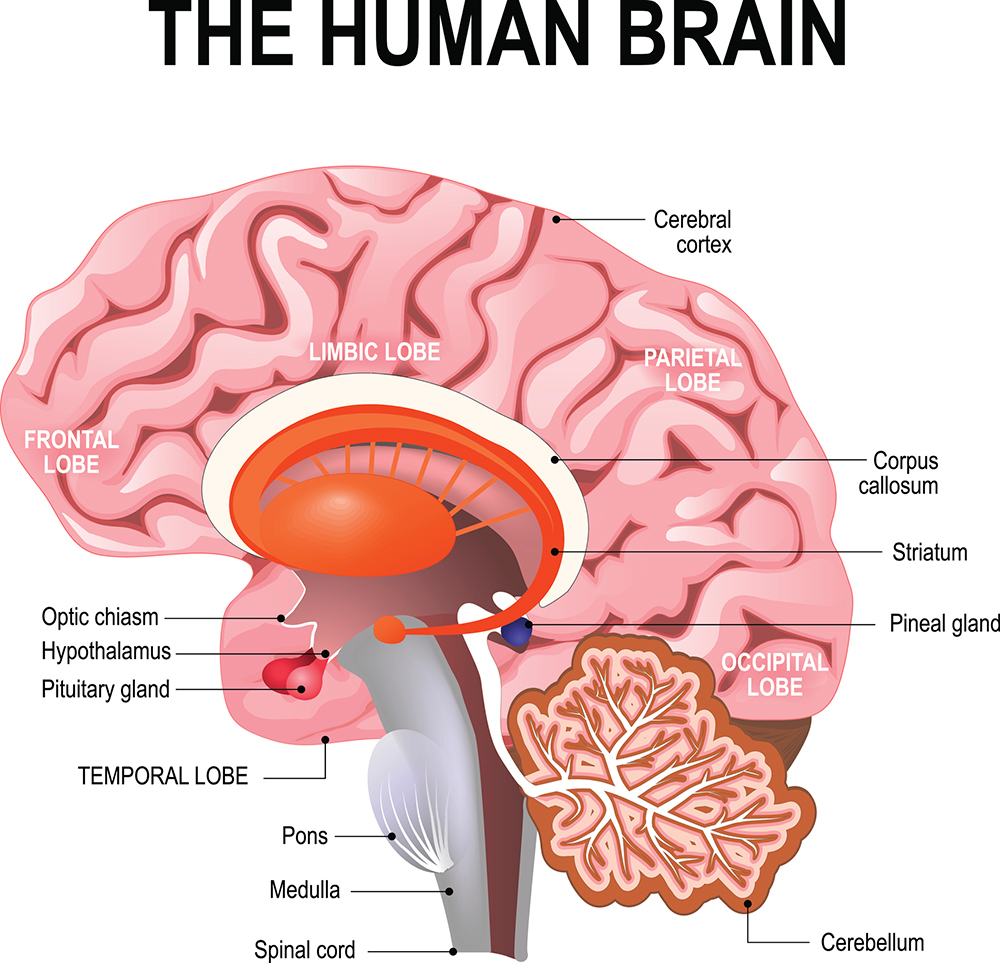

The decision-making circuits commonly associated with schizophrenia and substance use disorder include areas of the “cortex” – the outer part of our brain important for complex thought (especially the frontal lobe) – that “talk” to hub areas such as the “striatum”. The striatum lets us select and then initiate an action to achieve a specific goal.

Different cortical areas are used to compute different processes in the brain. The prefrontal cortex helps us understand when a strategy needed for success changes. So, if we replaced all the traffic lights with sirens, the prefrontal cortex would help us realise this and adjust.

When the anticipated outcome of a choice changes (such as if A was better, but then suddenly B became better), the orbitofrontal cortex helps us identify this. Similarly, the striatum is key for anticipating what an outcome will be and when we will get the reward.

Dopamine helps make choice a reality

Extensive research efforts have found the brains of people experiencing schizophrenia function differently in multiple areas. It’s believed this could contribute to decision-making problems.

For the psychotic symptoms observed in schizophrenia (such as hallucinations and delusions), alterations in the neurotransmitter dopamine are important. Dopamine is a chemical in the brain that’s key for anticipating rewards, making decisions and controlling the physical actions necessary to act on our choices.

In our research , we’ve argued increases in dopamine in the striatum may cause problems with how the brain integrates information from the cortex, resulting in decision-making difficulties. However, this may only be the case in some individuals .

Stimulants also cause excessive dopamine release. They can alter the balance between goal-directed behaviours, which are flexible and respond to environmental changes – and habits, which are automatic and hard to break.

Usually, when we learn something new our brain keeps adapting and incorporating new information. But this is slow and cognitively demanding. Substance dependence can accelerate a person’s progression to habitual behaviour, wherein a set strategy or response become ingrained.

This then makes it hard to stop seeking drugs, even if the individual no longer finds them enjoyable .

How to help people make better decisions

Unfortunately, problems with cognitive ability are hard to treat. There are no medications for schizophrenia or stimulant dependence shown to reliably improve cognition . This is a consequence of the human brain’s complexity.

That said, there are ways we can all improve our memory and decision-making, which may also help those with mental illnesses causing cognition problems.

For instance, cognitive remediation therapy is a behavioural approach that trains the brain to respond to certain situations better. For people with schizophrenia, it may improve visual memory and perhaps more complex decision-making.

Not being able to navigate decisions day-to-day is one of the most debilitating aspects of disorders that impact cognition. This leads to difficulties in maintaining work, keeping friends and leading a fulfilling life.

We need more research to understand how different brains make different decisions. Hopefully then we can improve the lives of those living with mental illness.

James Kesby , UQ Amplify Researcher, The University of Queensland and Shuichi Suetani , Psychiatrist, Queensland Brain Institute, The University of Queensland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article .

- Builders transform parking lot into avenue for dementia rese...

- The importance of brain health to prevent dementia

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Open access

- Published: 06 December 2017

Food for thought: how nutrition impacts cognition and emotion

- Sarah J. Spencer 1 ,

- Aniko Korosi 2 ,

- Sophie Layé 3 ,

- Barbara Shukitt-Hale 4 &

- Ruth M. Barrientos 5

npj Science of Food volume 1 , Article number: 7 ( 2017 ) Cite this article

153k Accesses

147 Citations

189 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Neuroendocrine diseases

More than one-third of American adults are obese and statistics are similar worldwide. Caloric intake and diet composition have large and lasting effects on cognition and emotion, especially during critical periods in development, but the neural mechanisms for these effects are not well understood. A clear understanding of the cognitive–emotional processes underpinning desires to over-consume foods can assist more effective prevention and treatments of obesity. This review addresses recent work linking dietary fat intake and omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid dietary imbalance with inflammation in developing, adult, and aged brains. Thus, early-life diet and exposure to stress can lead to cognitive dysfunction throughout life and there is potential for early nutritional interventions (e.g., with essential micronutrients) for preventing these deficits. Likewise, acute consumption of a high-fat diet primes the hippocampus to produce a potentiated neuroinflammatory response to a mild immune challenge, causing memory deficits. Low dietary intake of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids can also contribute to depression through its effects on endocannabinoid and inflammatory pathways in specific brain regions leading to synaptic phagocytosis by microglia in the hippocampus, contributing to memory loss. However, encouragingly, consumption of fruits and vegetables high in polyphenolics can prevent and even reverse age-related cognitive deficits by lowering oxidative stress and inflammation. Understanding relationships between diet, cognition, and emotion is necessary to uncover mechanisms involved in and strategies to prevent or attenuate comorbid neurological conditions in obese individuals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Microdosing with psilocybin mushrooms: a double-blind placebo-controlled study

Alzheimer’s disease risk reduction in clinical practice: a priority in the emerging field of preventive neurology

Investigating nutrient biomarkers of healthy brain aging: a multimodal brain imaging study

Introduction.

Cognitive and emotional dysfunctions are an increasing burden in our society. The exact factors and underlying mechanisms precipitating these disorders have not yet been elucidated. Next to our genetic makeup, the interplay between specific environmental challenges occurring during well-defined developmental periods seems to play an important role. Interestingly, such brain dysfunction most often co-occurs with metabolic disorders (e.g., obesity) and/or poor dietary habits; obesity and poor diet can lead to negative health implications including cognitive and mood dysfunctions, suggesting a strong interaction between these elements (Fig. 1 ). Obesity is a global phenomenon, with around 38% of adults and 18% of children and adolescents worldwide classified as either overweight or obese. 1 Even in the absence of obesity, poor diet is commonplace, 2 with, for instance, many eating foods that are highly processed and lacking in important polyphenols and anti-oxidants or that contain well-below the recommended levels of omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA). In this review, we will discuss the extent of, and mechanisms for, diet’s influence on mood and cognition during different stages of life, with a focus on microglial activation, glucocorticoids and endocannabinoids (eCBs).

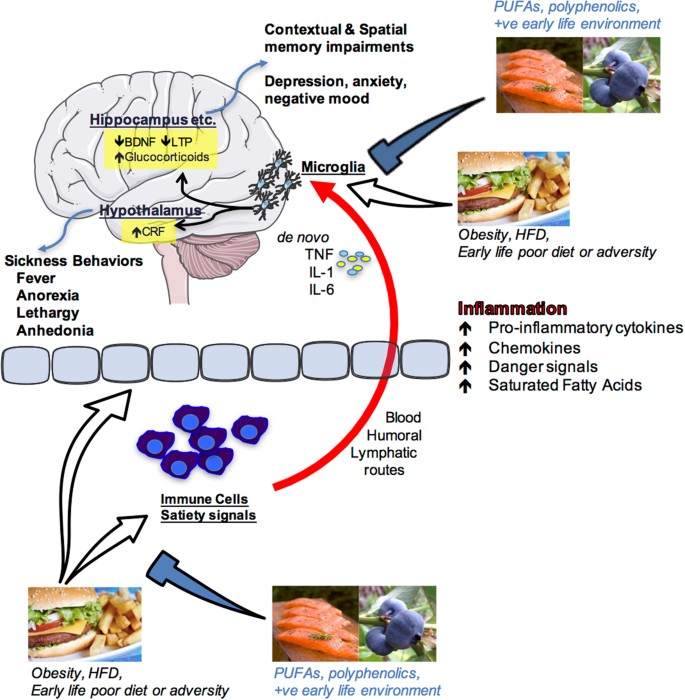

Schematic depiction of how nutrition influences cognition and emotion. Overeating, obesity, acute high-fat diet consumption, poor early-life diet or early life adversity can produce an inflammatory response in peripheral immune cells and centrally as well as having impact upon the blood–brain interface and circulating factors that regulate satiety. Peripheral pro-inflammatory molecules (cytokines, chemokines, danger signals, fatty acids) can signal the immune cells of the brain (most likely microglia) via blood-borne, humoral, and/or lymphatic routes. These signals can either sensitize or activate microglia leading to de novo production of pro-inflammatory molecules such as interleukin-1beta (IL1β), IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) within brain structures that are known to mediate cognition (hippocampus) and emotion (hypothalamus, amygdala, prefrontal cortex and others). Amplified inflammation in these regions impairs proper functioning leading to memory impairments and/or depressive-like behaviors. Polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA), polyphenolics, and a positive (+ve) early life environment (appropriate nutrition and absence of significant stress or adversity) can prevent these negative outcomes by regulating peripheral and central immune cell activity. Images are adapted from Servier Medical Art, which is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Unported License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/ . Salmon and hamburger images were downloaded from Bing.com with the License filter set to “free to share, and use commercially”. The blueberry image is courtesy of author Assistant Prof. Ruth Barrientos

Perinatal diet disrupts cognitive function long-term, a role for microglia

Poor diet in utero and during early postnatal life can cause lasting changes in many aspects of metabolic and central functions, including impairments in cognition and accelerated brain aging, 3 but see. 4 Maternal gestational diabetes and even a junk food diet in the non-diabetic can lead to metabolic complications, including diabetes and obesity in the offspring. 5 , 6 It can also cause changes in reward processing in the offspring brain such that they grow to prefer foods high in fat and sucrose. 7 , 8 Similarly, early introduction of solid food in children and high childhood consumption of fatty foods and sweetened drinks can accelerate weight gain and lead to metabolic complications long-term that may be associated with poorer executive function. 9 On the other hand, some dietary supplements can positively influence cognition, as is seen with supplementation of baby formula with long chain omega-3 PUFA improving cognition in babies. 10 In these randomized control trials (RCTs), an omega-3 PUFA-enriched formula beginning shortly after birth, or 6 weeks’ breast feeding, significantly improved performance of 9-month old babies on a problem solving task (a two-step task to retrieve a rattle, known to correlate with performance on IQ tasks).

From animal models, it is clear that the effects of diet in early life are far-reaching. Even obesity in rat sires (that play no part in rearing the offspring) leads to pancreatic beta cell dysfunction in female offspring, which can be passed on to the next generation. 11 Obesity and high-fat diet feeding in rat and mouse dams during pregnancy and lactation leads to impairments in several tests of mood, including those modeling depressive and anxious behaviors, as well as negatively impacting cognition. 12 Diet in the post-partum to weaning period can impact similar behaviors. 13

Additional to the impact of a prenatal diet, over-consumption of the mother’s milk during the first 3 weeks of a rat’s life leads to lasting obesity in males and females. 14 This neonatal overfeeding also disrupts cognitive function. For example, neonatally overfed rats perform poorly in the novel object recognition test and in the delayed spatial win-shift radial arm maze, as adults, compared with control rats. 15 These findings are interesting to compare with the effects of poor diet in adults where a longer-term high-fat diet (around 20 weeks in the rat) 16 , 17 , 18 and / or high-fat diet in conjunction with a pre-diabetic phenotype 19 is necessary to induce cognitive dysfunction. While there are no differences in post-learning synaptogenesis (synaptophysin) or apoptosis (caspase-3) to explain the effects seen in the neonatally overfed, these rats do have an impaired microglial response to the learning task. 15

Microglia are one of the major immune cell populations in the brain. In development, they are essential for synaptic pruning, while in a mature animal their major role is in mounting a pro-inflammatory immune response and phagocytosing pathogens and injured brain cells. 20 Hyper-activated microglia can lead to cognitive dysfunction through excess pro-inflammatory cytokine production causing impaired long-term potentiation-induction, reduced production of plasticity-related molecules including brain-derived neurotrophic factor and insulin-like growth factor-1, and reduced synaptic plasticity 20 However, an appropriate microglial response may also be essential for effective learning.

Neonatally overfed rats have more microglia in the CA1 region of the hippocampus at postnatal day 14, i.e., while they still have access to excess maternal milk and are undergoing accelerated weight gain. These microglia also have larger soma and retracted processes, indicative of a more activated phenotype. By the time these rats reach adulthood, there persists an increase in the area immunolabelled with microglial marker Iba1 in the dentate gyrus. In the neonatally overfed, the microglial response to a learning task is less robust than in controls. This effect is associated with a suppression of cell proliferation in control animals relative to the neonatally overfed, potentially to preserve existing neuronal networks and minimize novel inputs while learning takes place. 21 Interestingly, global inducible microglial and monocyte depletion can lead to improved performance in the Barnes maze, 22 suggesting withdrawal of microglial activity at specific learning phases is important for learning. These findings implicate microglia in the long-term effects of early life overfeeding on cognition suggesting normal microglia must be able to robustly respond to learning tasks and neonatal overfeeding impairs their ability to do so.

Neuroinflammatory processes, including the role of microglia, can clearly be impacted by neonatal diet and represent at least one contributing mechanism for how cognitive function is affected. Neuroinflammation and microglia can also be impacted by other early life events and play a significant role in how stress during development alters long-term physiology.

Early-life stress (ES) programs vulnerability to cognitive disorders

ES alters brain structure and function life-long, leading to increased vulnerability to develop emotional and cognitive disorders as is evident from several preclinical and clinical studies. 23 , 24 , 25 The exact underlying mechanisms for such programming remain elusive. There is extensive seminal work indicating a key role for sensory stimuli from the mother and neuroendocrine factors (e.g., stress hormones) in this programming, 26 , 27 however it has been recently suggested that these factors might act synergistically with metabolic and nutritional elements. 28 In fact, ES is associated with increased vulnerability to develop metabolic disorders such as obesity, which mostly co-occur with cognitive deficits, 29 , 30 and both ES and an adverse early nutritional environment lead to strikingly similar cognitive impairments later in life, 28 , 31 suggesting that metabolic factors and nutritional elements might mediate some of the ES effects on brain structure and function.

The brain has a very high demand for nutrients in this early period and nutritional imbalances affect normal neurodevelopment resulting in lasting cognitive deficits. 32 Understanding the role of metabolic factors and specific nutrients in this context is key to develop effective peripheral (e.g., nutritional) intervention strategies. A mouse model of the chronic ES of limited nesting and bedding material during the first postnatal week has been shown to lead to aberrant maternal care, which leads to cognitive decline in the ES offspring. 24 , 33 , 34

The hippocampus, a brain region key for cognitive functions, is permanently altered in its structure and function in these ES-exposed offspring. The hippocampus is in fact particularly sensitive to the early-life environment as it continues its development into the postnatal period. 35 Adult neurogenesis (AN) is a unique form of plasticity, which takes place in the hippocampus, consisting of the proliferation of neuronal progenitor cells that differentiate and mature into fully functional neurons that subsequently integrate into the existing hippocampal circuitry. These newly formed neurons are involved in various aspects of hippocampus-dependent learning and memory. 36 AN is affected persistently by ES 24 , 37 and, more precisely, while ES exposure initially increases neurogenesis (i.e., proliferation and differentiation of newborn cells) at postnatal day 9, at later time points (postnatal day 150), the survival of the newly born cells is reduced. 24 In addition, ES affects the neuroinflammatory profile in a lasting manner, with, for example, increased CD68 (phagocytic microglia expression) in adulthood. 38

Importantly, ES persistently affects peripheral adipose tissue metabolism as well. White adipose mass (WAT), plasma leptin (the adipokine released from the WAT) and leptin mRNA expression in WAT are persistently reduced in ES-exposed offspring. 39 In addition, exposure of ES mice to an unhealthy western style diet, leads to a higher increase in adiposity in these mice when compared to controls. These findings suggest that ES exposure leads to metabolic dysregulation and a greater vulnerability to develop obesity in a moderately obesogenic environment. Whether these metabolic alterations contribute to the ES-induced cognitive deficits warrants further investigation. 39

In addition to peripheral metabolism, ES-induced alterations in the nutritional composition of the dam’s milk, and/or nutrient intake/absorption by the pup 25 , 28 , 40 could have lasting consequences for brain structure and function. Indeed, the essential micronutrient, methionine, a critical component of the one-carbon (1-C) metabolism that is required for methylation, and for synthesis of proteins, phospholipids and neurotransmitters, is reduced after ES exposure in plasma and hippocampus of postnatal day 9 offspring. Importantly, a short supplementation of the maternal diet only during ES exposure with essential 1-C metabolism-associated micronutrients not only restores methionine levels peripherally as well as centrally, but rescues (some of) the effects of ES on hippocampal cognitive measures in adulthood and prevents the ES-induced hypothalamic-pituitary–adrenal axis hyperactivity at postnatal day 9. 25

These studies highlight the importance of studying metabolic factors and nutrients in the ES-induced effects on the brain. In the near future, it will be key to further understand the exact mechanisms mediating the effects of nutrients and metabolic factors and the windows of opportunity for interventions on brain function, as this will open entirely new avenues for targeted nutrition for vulnerable populations. However, while the early life period is a window of particular vulnerability to the programming effects of diet and other environmental influences, diet at other phases of life is also important in dictating mood and cognition.

Adult consumption of a high-fat diet: a vulnerability factor for hippocampal-dependent memory

Adults in developed countries are consuming diets higher in saturated fats and/or refined sugars than ever before. Indeed, recent reports show that approximately 12% of American adults’ daily energy intake comes from saturated fats and 13% from added sugars, 41 significantly more than what is recommended (5–10%) by the US Department of Agriculture and the Department of Health and Human Services. Not surprisingly, these dietary habits have contributed to the increasing prevalence of obesity among adults, which is currently approximately 37% in the US, a sharp rise from the 13% prevalence rate of 1960. 42

These statistics are alarming because aside from its well-known provocation of cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndrome, and type 2 diabetes, obesity has now also been associated with mild cognitive impairments and dementia. There is growing evidence that neuroinflammation may underlie obesity-induced cognitive deficits. 9 Recently, studies have demonstrated that short-term consumption (1–7 days) of an unhealthy diet (e.g., high saturated fat and/or high sugar) triggers neuroinflammatory processes, suggesting that obesity per se may not be necessary to cause cognitive disruptions. 43 , 44 For the last 10–15 years, the hypothalamus has received the vast majority of the attention with regard to obesity-induced neuroinflammatory responses and functional declines, 45 perhaps due to its close proximity to the third ventricle, circumventricular organs, and mediobasal eminence, where inflammatory signals from the periphery have easier entry into the brain. Indeed, long chain saturated fatty acids have been shown to directly pass into the hypothalamus producing an inflammatory response there through activation of toll-like receptor 4 signaling. 46 , 47 This active passage of saturated fatty acids, however, has not been observed in the hippocampus, a key brain region that mediates learning and memory. 46 Nonetheless, high-fat diet consumption has been demonstrated to impair hippocampus-dependent memory function in humans and rodents. For example, compared to rodents that consumed a control diet, those that consumed a high-fat and/or high-sugar diet exhibited robust impairments in various types of memory (e.g., spatial, contextual), as indicated by weaker performances in the Y-maze, 48 radial arm maze, 15 novel object recognition task, 15 novel place recognition task, 44 , 49 Morris water maze, 50 and contextual fear conditioning. 18 , 51 Also, adult humans who consumed a high-fat diet for 5 days exhibited significantly reduced focused attention and reduced retrieval speed of information from working and episodic memory, compared with those who consumed a standard diet. 52

Many of these studies, and others, have shown that high-fat diet-induced cognitive deteriorations are accompanied by elevated neuroinflammatory markers or responses in the hippocampus. 15 , 18 , 44 , 48 , 49 , 50 , 51 , 53 However, the mechanisms by which these neuroinflammatory processes signal and/or affect the hippocampus are not entirely clear. There is growing evidence that high-fat diets may compromise the hippocampus by sensitizing the immune cells (most likely microglia) of this brain structure, thus priming the inflammatory response to subsequent challenging stimuli. 18 , 50 , 51 For example, one study demonstrated that adult rats that had eaten a high-fat diet for 5 months exhibited a sensitized hippocampus such that when they received a relatively mild stressor (a single, 2 s, 1.5 mA footshock) following a learning session the neuroinflammatory response in the hippocampus was potentiated compared to the response of rats that had eaten the regular chow, and this response led to deficits in long-term contextual memory. 18 Another study showed that just 3 days of consuming a high-fat diet was sufficient to sensitize the hippocampus of adult rats. Here, a low-dose peripheral immune challenge (with lipopolysaccharide; LPS) produced an exaggerated neuroinflammatory response in the hippocampus of these rats compared to those that consumed the regular chow, and also led to contextual memory deficits. 51