- Browse All Articles

- Newsletter Sign-Up

Leadership →

- 01 May 2024

- What Do You Think?

Have You Had Enough?

James Heskett has been asking readers, “What do you think?” for 24 years on a wide variety of management topics. In this farewell column, Heskett reflects on the changing leadership landscape and thanks his readers for consistently weighing in over the years. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 26 Apr 2024

Deion Sanders' Prime Lessons for Leading a Team to Victory

The former star athlete known for flash uses unglamorous command-and-control methods to get results as a college football coach. Business leaders can learn 10 key lessons from the way 'Coach Prime' builds a culture of respect and discipline without micromanaging, says Hise Gibson.

- 26 Mar 2024

- Cold Call Podcast

How Do Great Leaders Overcome Adversity?

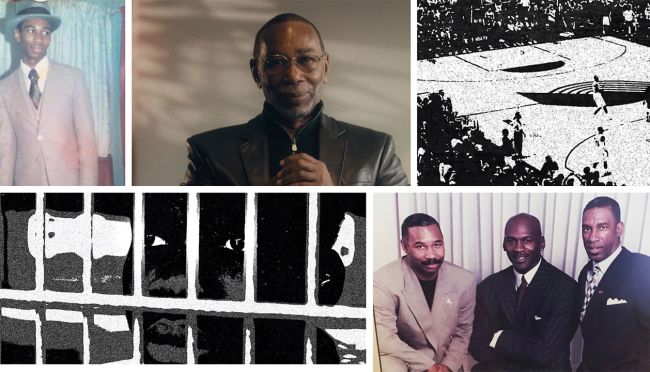

In the spring of 2021, Raymond Jefferson (MBA 2000) applied for a job in President Joseph Biden’s administration. Ten years earlier, false allegations were used to force him to resign from his prior US government position as assistant secretary of labor for veterans’ employment and training in the Department of Labor. Two employees had accused him of ethical violations in hiring and procurement decisions, including pressuring subordinates into extending contracts to his alleged personal associates. The Deputy Secretary of Labor gave Jefferson four hours to resign or be terminated. Jefferson filed a federal lawsuit against the US government to clear his name, which he pursued for eight years at the expense of his entire life savings. Why, after such a traumatic and debilitating experience, would Jefferson want to pursue a career in government again? Harvard Business School Senior Lecturer Anthony Mayo explores Jefferson’s personal and professional journey from upstate New York to West Point to the Obama administration, how he faced adversity at several junctures in his life, and how resilience and vulnerability shaped his leadership style in the case, "Raymond Jefferson: Trial by Fire."

- 24 Jan 2024

Why Boeing’s Problems with the 737 MAX Began More Than 25 Years Ago

Aggressive cost cutting and rocky leadership changes have eroded the culture at Boeing, a company once admired for its engineering rigor, says Bill George. What will it take to repair the reputational damage wrought by years of crises involving its 737 MAX?

- 02 Jan 2024

Do Boomerang CEOs Get a Bad Rap?

Several companies have brought back formerly successful CEOs in hopes of breathing new life into their organizations—with mixed results. But are we even measuring the boomerang CEOs' performance properly? asks James Heskett. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- Research & Ideas

10 Trends to Watch in 2024

Employees may seek new approaches to balance, even as leaders consider whether to bring more teams back to offices or make hybrid work even more flexible. These are just a few trends that Harvard Business School faculty members will be following during a year when staffing, climate, and inclusion will likely remain top of mind.

- 12 Dec 2023

Can Sustainability Drive Innovation at Ferrari?

When Ferrari, the Italian luxury sports car manufacturer, committed to achieving carbon neutrality and to electrifying a large part of its car fleet, investors and employees applauded the new strategy. But among the company’s suppliers, the reaction was mixed. Many were nervous about how this shift would affect their bottom lines. Professor Raffaella Sadun and Ferrari CEO Benedetto Vigna discuss how Ferrari collaborated with suppliers to work toward achieving the company’s goal. They also explore how sustainability can be a catalyst for innovation in the case, “Ferrari: Shifting to Carbon Neutrality.” This episode was recorded live December 4, 2023 in front of a remote studio audience in the Live Online Classroom at Harvard Business School.

- 05 Dec 2023

Lessons in Decision-Making: Confident People Aren't Always Correct (Except When They Are)

A study of 70,000 decisions by Thomas Graeber and Benjamin Enke finds that self-assurance doesn't necessarily reflect skill. Shrewd decision-making often comes down to how well a person understands the limits of their knowledge. How can managers identify and elevate their best decision-makers?

- 21 Nov 2023

The Beauty Industry: Products for a Healthy Glow or a Compact for Harm?

Many cosmetics and skincare companies present an image of social consciousness and transformative potential, while profiting from insecurity and excluding broad swaths of people. Geoffrey Jones examines the unsightly reality of the beauty industry.

- 14 Nov 2023

Do We Underestimate the Importance of Generosity in Leadership?

Management experts applaud leaders who are, among other things, determined, humble, and frugal, but rarely consider whether they are generous. However, executives who share their time, talent, and ideas often give rise to legendary organizations. Does generosity merit further consideration? asks James Heskett. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 24 Oct 2023

From P.T. Barnum to Mary Kay: Lessons From 5 Leaders Who Changed the World

What do Steve Jobs and Sarah Breedlove have in common? Through a series of case studies, Robert Simons explores the unique qualities of visionary leaders and what today's managers can learn from their journeys.

- 06 Oct 2023

Yes, You Can Radically Change Your Organization in One Week

Skip the committees and the multi-year roadmap. With the right conditions, leaders can confront even complex organizational problems in one week. Frances Frei and Anne Morriss explain how in their book Move Fast and Fix Things.

- 26 Sep 2023

The PGA Tour and LIV Golf Merger: Competition vs. Cooperation

On June 9, 2022, the first LIV Golf event teed off outside of London. The new tour offered players larger prizes, more flexibility, and ambitions to attract new fans to the sport. Immediately following the official start of that tournament, the PGA Tour announced that all 17 PGA Tour players participating in the LIV Golf event were suspended and ineligible to compete in PGA Tour events. Tensions between the two golf entities continued to rise, as more players “defected” to LIV. Eventually LIV Golf filed an antitrust lawsuit accusing the PGA Tour of anticompetitive practices, and the Department of Justice launched an investigation. Then, in a dramatic turn of events, LIV Golf and the PGA Tour announced that they were merging. Harvard Business School assistant professor Alexander MacKay discusses the competitive, antitrust, and regulatory issues at stake and whether or not the PGA Tour took the right actions in response to LIV Golf’s entry in his case, “LIV Golf.”

- 01 Aug 2023

As Leaders, Why Do We Continue to Reward A, While Hoping for B?

Companies often encourage the bad behavior that executives publicly rebuke—usually in pursuit of short-term performance. What keeps leaders from truly aligning incentives and goals? asks James Heskett. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 05 Jul 2023

What Kind of Leader Are You? How Three Action Orientations Can Help You Meet the Moment

Executives who confront new challenges with old formulas often fail. The best leaders tailor their approach, recalibrating their "action orientation" to address the problem at hand, says Ryan Raffaelli. He details three action orientations and how leaders can harness them.

How Are Middle Managers Falling Down Most Often on Employee Inclusion?

Companies are struggling to retain employees from underrepresented groups, many of whom don't feel heard in the workplace. What do managers need to do to build truly inclusive teams? asks James Heskett. Open for comment; 0 Comments.

- 14 Jun 2023

Every Company Should Have These Leaders—or Develop Them if They Don't

Companies need T-shaped leaders, those who can share knowledge across the organization while focusing on their business units, but they should be a mix of visionaries and tacticians. Hise Gibson breaks down the nuances of each leader and how companies can cultivate this talent among their ranks.

Four Steps to Building the Psychological Safety That High-Performing Teams Need

Struggling to spark strategic risk-taking and creative thinking? In the post-pandemic workplace, teams need psychological safety more than ever, and a new analysis by Amy Edmondson highlights the best ways to nurture it.

- 31 May 2023

From Prison Cell to Nike’s C-Suite: The Journey of Larry Miller

VIDEO: Before leading one of the world’s largest brands, Nike executive Larry Miller served time in prison for murder. In this interview, Miller shares how education helped him escape a life of crime and why employers should give the formerly incarcerated a second chance. Inspired by a Harvard Business School case study.

- 23 May 2023

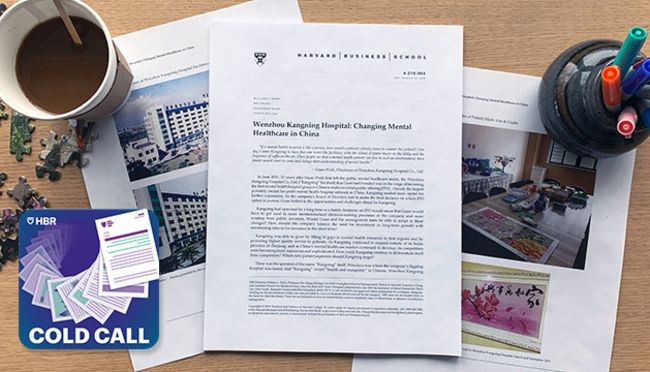

The Entrepreneurial Journey of China’s First Private Mental Health Hospital

The city of Wenzhou in southeastern China is home to the country’s largest privately owned mental health hospital group, the Wenzhou Kangning Hospital Co, Ltd. It’s an example of the extraordinary entrepreneurship happening in China’s healthcare space. But after its successful initial public offering (IPO), how will the hospital grow in the future? Harvard Professor of China Studies William C. Kirby highlights the challenges of China’s mental health sector and the means company founder Guan Weili employed to address them in his case, Wenzhou Kangning Hospital: Changing Mental Healthcare in China.

- Search Menu

- Sign in through your institution

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Anglo-Saxon and Medieval Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Archaeology by Region

- Archaeology of Religion

- Archaeology of Trade and Exchange

- Biblical Archaeology

- Contemporary and Public Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- History and Theory of Archaeology

- Industrial Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Mortuary Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Underwater Archaeology

- Zooarchaeology

- Browse content in Architecture

- Architectural Structure and Design

- History of Architecture

- Residential and Domestic Buildings

- Theory of Architecture

- Browse content in Art

- Art Subjects and Themes

- History of Art

- Industrial and Commercial Art

- Theory of Art

- Biographical Studies

- Byzantine Studies

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Philosophy

- Classical Mythology

- Classical Literature

- Classical Reception

- Classical Art and Architecture

- Classical Oratory and Rhetoric

- Greek and Roman Papyrology

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Law

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Digital Humanities

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Environmental History

- Genealogy, Heraldry, Names, and Honours

- Genocide and Ethnic Cleansing

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Emotions

- History of Agriculture

- History of Education

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Industrial History

- Intellectual History

- International History

- Labour History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Local and Family History

- Maritime History

- Military History

- National Liberation and Post-Colonialism

- Oral History

- Political History

- Public History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- Urban History

- World History

- Browse content in Language Teaching and Learning

- Language Learning (Specific Skills)

- Language Teaching Theory and Methods

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Applied Linguistics

- Cognitive Linguistics

- Computational Linguistics

- Forensic Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- History of English

- Language Evolution

- Language Reference

- Language Acquisition

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Lexicography

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Phonetics and Phonology

- Psycholinguistics

- Sociolinguistics

- Translation and Interpretation

- Writing Systems

- Browse content in Literature

- Bibliography

- Children's Literature Studies

- Literary Studies (Romanticism)

- Literary Studies (American)

- Literary Studies (Asian)

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies (Eco-criticism)

- Literary Studies (Modernism)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (African American Literature)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Gender Studies)

- Literary Studies (Graphic Novels)

- Literary Studies (History of the Book)

- Literary Studies (Plays and Playwrights)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Postcolonial Literature)

- Literary Studies (Queer Studies)

- Literary Studies (Science Fiction)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (War Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Shakespeare Studies and Criticism

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Applied Music

- Dance and Music

- Ethics in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Gender and Sexuality in Music

- Medicine and Music

- Music Cultures

- Music and Media

- Music and Religion

- Music and Culture

- Music Education and Pedagogy

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Scores, Lyrics, and Libretti

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Performance Practice and Studies

- Race and Ethnicity in Music

- Sound Studies

- Browse content in Performing Arts

- Browse content in Philosophy

- Aesthetics and Philosophy of Art

- Epistemology

- Feminist Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Moral Philosophy

- Non-Western Philosophy

- Philosophy of Language

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Perception

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Action

- Philosophy of Law

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Practical Ethics

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- East Asian Religions

- History of Religion

- Judaism and Jewish Studies

- Qumran Studies

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Health

- Religion and Politics

- Religion and Science

- Religion and Law

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cookery, Food, and Drink

- Cultural Studies

- Customs and Traditions

- Ethical Issues and Debates

- Hobbies, Games, Arts and Crafts

- Natural world, Country Life, and Pets

- Popular Beliefs and Controversial Knowledge

- Sports and Outdoor Recreation

- Technology and Society

- Travel and Holiday

- Visual Culture

- Browse content in Law

- Arbitration

- Browse content in Company and Commercial Law

- Commercial Law

- Company Law

- Browse content in Comparative Law

- Systems of Law

- Competition Law

- Browse content in Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Government Powers

- Judicial Review

- Local Government Law

- Military and Defence Law

- Parliamentary and Legislative Practice

- Construction Law

- Contract Law

- Browse content in Criminal Law

- Criminal Procedure

- Criminal Evidence Law

- Sentencing and Punishment

- Employment and Labour Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Browse content in Financial Law

- Banking Law

- Insolvency Law

- History of Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Intellectual Property Law

- Browse content in International Law

- Private International Law and Conflict of Laws

- Public International Law

- IT and Communications Law

- Jurisprudence and Philosophy of Law

- Law and Politics

- Law and Society

- Browse content in Legal System and Practice

- Courts and Procedure

- Legal Skills and Practice

- Primary Sources of Law

- Regulation of Legal Profession

- Medical and Healthcare Law

- Browse content in Policing

- Criminal Investigation and Detection

- Police and Security Services

- Police Procedure and Law

- Police Regional Planning

- Browse content in Property Law

- Personal Property Law

- Study and Revision

- Terrorism and National Security Law

- Browse content in Trusts Law

- Wills and Probate or Succession

- Browse content in Medicine and Health

- Browse content in Allied Health Professions

- Arts Therapies

- Clinical Science

- Dietetics and Nutrition

- Occupational Therapy

- Operating Department Practice

- Physiotherapy

- Radiography

- Speech and Language Therapy

- Browse content in Anaesthetics

- General Anaesthesia

- Neuroanaesthesia

- Clinical Neuroscience

- Browse content in Clinical Medicine

- Acute Medicine

- Cardiovascular Medicine

- Clinical Genetics

- Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics

- Dermatology

- Endocrinology and Diabetes

- Gastroenterology

- Genito-urinary Medicine

- Geriatric Medicine

- Infectious Diseases

- Medical Toxicology

- Medical Oncology

- Pain Medicine

- Palliative Medicine

- Rehabilitation Medicine

- Respiratory Medicine and Pulmonology

- Rheumatology

- Sleep Medicine

- Sports and Exercise Medicine

- Community Medical Services

- Critical Care

- Emergency Medicine

- Forensic Medicine

- Haematology

- History of Medicine

- Browse content in Medical Skills

- Clinical Skills

- Communication Skills

- Nursing Skills

- Surgical Skills

- Browse content in Medical Dentistry

- Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery

- Paediatric Dentistry

- Restorative Dentistry and Orthodontics

- Surgical Dentistry

- Medical Ethics

- Medical Statistics and Methodology

- Browse content in Neurology

- Clinical Neurophysiology

- Neuropathology

- Nursing Studies

- Browse content in Obstetrics and Gynaecology

- Gynaecology

- Occupational Medicine

- Ophthalmology

- Otolaryngology (ENT)

- Browse content in Paediatrics

- Neonatology

- Browse content in Pathology

- Chemical Pathology

- Clinical Cytogenetics and Molecular Genetics

- Histopathology

- Medical Microbiology and Virology

- Patient Education and Information

- Browse content in Pharmacology

- Psychopharmacology

- Browse content in Popular Health

- Caring for Others

- Complementary and Alternative Medicine

- Self-help and Personal Development

- Browse content in Preclinical Medicine

- Cell Biology

- Molecular Biology and Genetics

- Reproduction, Growth and Development

- Primary Care

- Professional Development in Medicine

- Browse content in Psychiatry

- Addiction Medicine

- Child and Adolescent Psychiatry

- Forensic Psychiatry

- Learning Disabilities

- Old Age Psychiatry

- Psychotherapy

- Browse content in Public Health and Epidemiology

- Epidemiology

- Public Health

- Browse content in Radiology

- Clinical Radiology

- Interventional Radiology

- Nuclear Medicine

- Radiation Oncology

- Reproductive Medicine

- Browse content in Surgery

- Cardiothoracic Surgery

- Gastro-intestinal and Colorectal Surgery

- General Surgery

- Neurosurgery

- Paediatric Surgery

- Peri-operative Care

- Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery

- Surgical Oncology

- Transplant Surgery

- Trauma and Orthopaedic Surgery

- Vascular Surgery

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Biological Sciences

- Aquatic Biology

- Biochemistry

- Bioinformatics and Computational Biology

- Developmental Biology

- Ecology and Conservation

- Evolutionary Biology

- Genetics and Genomics

- Microbiology

- Molecular and Cell Biology

- Natural History

- Plant Sciences and Forestry

- Research Methods in Life Sciences

- Structural Biology

- Systems Biology

- Zoology and Animal Sciences

- Browse content in Chemistry

- Analytical Chemistry

- Computational Chemistry

- Crystallography

- Environmental Chemistry

- Industrial Chemistry

- Inorganic Chemistry

- Materials Chemistry

- Medicinal Chemistry

- Mineralogy and Gems

- Organic Chemistry

- Physical Chemistry

- Polymer Chemistry

- Study and Communication Skills in Chemistry

- Theoretical Chemistry

- Browse content in Computer Science

- Artificial Intelligence

- Computer Architecture and Logic Design

- Game Studies

- Human-Computer Interaction

- Mathematical Theory of Computation

- Programming Languages

- Software Engineering

- Systems Analysis and Design

- Virtual Reality

- Browse content in Computing

- Business Applications

- Computer Security

- Computer Games

- Computer Networking and Communications

- Digital Lifestyle

- Graphical and Digital Media Applications

- Operating Systems

- Browse content in Earth Sciences and Geography

- Atmospheric Sciences

- Environmental Geography

- Geology and the Lithosphere

- Maps and Map-making

- Meteorology and Climatology

- Oceanography and Hydrology

- Palaeontology

- Physical Geography and Topography

- Regional Geography

- Soil Science

- Urban Geography

- Browse content in Engineering and Technology

- Agriculture and Farming

- Biological Engineering

- Civil Engineering, Surveying, and Building

- Electronics and Communications Engineering

- Energy Technology

- Engineering (General)

- Environmental Science, Engineering, and Technology

- History of Engineering and Technology

- Mechanical Engineering and Materials

- Technology of Industrial Chemistry

- Transport Technology and Trades

- Browse content in Environmental Science

- Applied Ecology (Environmental Science)

- Conservation of the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Environmental Sustainability

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Environmental Science)

- Management of Land and Natural Resources (Environmental Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environmental Science)

- Nuclear Issues (Environmental Science)

- Pollution and Threats to the Environment (Environmental Science)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Environmental Science)

- History of Science and Technology

- Browse content in Materials Science

- Ceramics and Glasses

- Composite Materials

- Metals, Alloying, and Corrosion

- Nanotechnology

- Browse content in Mathematics

- Applied Mathematics

- Biomathematics and Statistics

- History of Mathematics

- Mathematical Education

- Mathematical Finance

- Mathematical Analysis

- Numerical and Computational Mathematics

- Probability and Statistics

- Pure Mathematics

- Browse content in Neuroscience

- Cognition and Behavioural Neuroscience

- Development of the Nervous System

- Disorders of the Nervous System

- History of Neuroscience

- Invertebrate Neurobiology

- Molecular and Cellular Systems

- Neuroendocrinology and Autonomic Nervous System

- Neuroscientific Techniques

- Sensory and Motor Systems

- Browse content in Physics

- Astronomy and Astrophysics

- Atomic, Molecular, and Optical Physics

- Biological and Medical Physics

- Classical Mechanics

- Computational Physics

- Condensed Matter Physics

- Electromagnetism, Optics, and Acoustics

- History of Physics

- Mathematical and Statistical Physics

- Measurement Science

- Nuclear Physics

- Particles and Fields

- Plasma Physics

- Quantum Physics

- Relativity and Gravitation

- Semiconductor and Mesoscopic Physics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Affective Sciences

- Clinical Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Cognitive Neuroscience

- Criminal and Forensic Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Health Psychology

- History and Systems in Psychology

- Music Psychology

- Neuropsychology

- Organizational Psychology

- Psychological Assessment and Testing

- Psychology of Human-Technology Interaction

- Psychology Professional Development and Training

- Research Methods in Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Anthropology of Religion

- Human Evolution

- Medical Anthropology

- Physical Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Theory and Practice of Anthropology

- Browse content in Business and Management

- Business Ethics

- Business Strategy

- Business History

- Business and Technology

- Business and Government

- Business and the Environment

- Comparative Management

- Corporate Governance

- Corporate Social Responsibility

- Entrepreneurship

- Health Management

- Human Resource Management

- Industrial and Employment Relations

- Industry Studies

- Information and Communication Technologies

- International Business

- Knowledge Management

- Management and Management Techniques

- Operations Management

- Organizational Theory and Behaviour

- Pensions and Pension Management

- Public and Nonprofit Management

- Strategic Management

- Supply Chain Management

- Browse content in Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Criminal Justice

- Criminology

- Forms of Crime

- International and Comparative Criminology

- Youth Violence and Juvenile Justice

- Development Studies

- Browse content in Economics

- Agricultural, Environmental, and Natural Resource Economics

- Asian Economics

- Behavioural Finance

- Behavioural Economics and Neuroeconomics

- Econometrics and Mathematical Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Systems

- Economic Methodology

- Economic Development and Growth

- Financial Markets

- Financial Institutions and Services

- General Economics and Teaching

- Health, Education, and Welfare

- History of Economic Thought

- International Economics

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Law and Economics

- Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Microeconomics

- Public Economics

- Urban, Rural, and Regional Economics

- Welfare Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Adult Education and Continuous Learning

- Care and Counselling of Students

- Early Childhood and Elementary Education

- Educational Equipment and Technology

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Higher and Further Education

- Organization and Management of Education

- Philosophy and Theory of Education

- Schools Studies

- Secondary Education

- Teaching of a Specific Subject

- Teaching of Specific Groups and Special Educational Needs

- Teaching Skills and Techniques

- Browse content in Environment

- Applied Ecology (Social Science)

- Climate Change

- Conservation of the Environment (Social Science)

- Environmentalist Thought and Ideology (Social Science)

- Natural Disasters (Environment)

- Social Impact of Environmental Issues (Social Science)

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Cultural Geography

- Economic Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Interdisciplinary Studies

- Communication Studies

- Museums, Libraries, and Information Sciences

- Browse content in Politics

- African Politics

- Asian Politics

- Chinese Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Elections and Electoral Studies

- Environmental Politics

- Ethnic Politics

- European Union

- Foreign Policy

- Gender and Politics

- Human Rights and Politics

- Indian Politics

- International Relations

- International Organization (Politics)

- International Political Economy

- Irish Politics

- Latin American Politics

- Middle Eastern Politics

- Political Behaviour

- Political Economy

- Political Institutions

- Political Methodology

- Political Communication

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Theory

- Politics and Law

- Politics of Development

- Public Policy

- Public Administration

- Quantitative Political Methodology

- Regional Political Studies

- Russian Politics

- Security Studies

- State and Local Government

- UK Politics

- US Politics

- Browse content in Regional and Area Studies

- African Studies

- Asian Studies

- East Asian Studies

- Japanese Studies

- Latin American Studies

- Middle Eastern Studies

- Native American Studies

- Scottish Studies

- Browse content in Research and Information

- Research Methods

- Browse content in Social Work

- Addictions and Substance Misuse

- Adoption and Fostering

- Care of the Elderly

- Child and Adolescent Social Work

- Couple and Family Social Work

- Direct Practice and Clinical Social Work

- Emergency Services

- Human Behaviour and the Social Environment

- International and Global Issues in Social Work

- Mental and Behavioural Health

- Social Justice and Human Rights

- Social Policy and Advocacy

- Social Work and Crime and Justice

- Social Work Macro Practice

- Social Work Practice Settings

- Social Work Research and Evidence-based Practice

- Welfare and Benefit Systems

- Browse content in Sociology

- Childhood Studies

- Community Development

- Comparative and Historical Sociology

- Economic Sociology

- Gender and Sexuality

- Gerontology and Ageing

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Marriage and the Family

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Theory

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Religion

- Sociology of Education

- Sport and Leisure

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Browse content in Warfare and Defence

- Defence Strategy, Planning, and Research

- Land Forces and Warfare

- Military Administration

- Military Life and Institutions

- Naval Forces and Warfare

- Other Warfare and Defence Issues

- Peace Studies and Conflict Resolution

- Weapons and Equipment

- < Previous chapter

- Next chapter >

37 Leadership Development: A Review and Agenda for Future Research

D. Scott DeRue, Stephen M. Ross School of Business, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan

Christopher G. Myers is a Ph.D. candidate in Management & Organizations at the University of Michigan’s Stephen M. Ross School of Business.

- Published: 16 December 2013

- Cite Icon Cite

- Permissions Icon Permissions

This chapter develops a conceptual framework that helps organize and synthesize key insights from the literature on leadership development. In this framework, called PREPARE, the authors call attention to the strategic purpose and desired results of leadership development in organizations. They emphasize how organizations can deliberately and systematically leverage a range of developmental experiences for enhancing the leadership capabilities of individuals, relationships, and collectives. Finally, they highlight how individuals and organizations vary in their approach to and support for leadership development, and how these differences explain variation in leadership development processes and outcomes. As an organizing mechanism for the existing literature, the PREPARE framework advances our understanding of what individuals and organizations can do to develop leadership talent, and highlights important questions for future research.

Introduction

Contemporary organizations operate in environments characterized by rapid change and increasing complexity. Indeed, some historians believe that our world is undergoing a transformation more profound and far-reaching than any experienced since the Industrial Revolution ( Daft, 2008 ). Advancements in technology are creating opportunities for new business models that can dramatically shift the competitive landscape of entire industries. Globalization and shifting geopolitical forces are permanently altering the boundaries of interorganizational collaboration and competition. In addition, a myriad of economic, environmental, and ethical crises are directly challenging the role of corporations in society, and highlighting the interdependence among business, government and social sectors. The result is organizations around the world and across a broad array of domains—industry, government, military, not-for-profit, health care, and education—are adapting their strategies, structures, and practices with the intent of becoming more agile and responsive to these dynamic environments.

Because of these ongoing organizational transformations, effective leadership is needed more than ever. Leadership is one of the most important predictors of whether groups and organizations are able to effectively adapt to and perform in dynamic environments ( Mintzberg & Waters, 1982 ; Peterson, Smith, Martorana, & Owens, 2003 ; Peterson, Walumbwa, Byron, & Myrowitz, 2009 ; Thomas, 1988 ; Waldman, Ramirez, House, & Puranam, 2001 ). As Bass and Bass (2008 , p. 11) concluded, “when an organization must be changed to reflect changes in technology, the environment, and the completion of programs, its leadership is critical in orchestrating that process.” Consequently, organizations are designating leadership as a top strategic priority and potential source of competitive advantage, and are investing in its development accordingly ( Day, Harrison, & Halpin, 2009 ). For example, in 2009, almost a quarter of the $50 billion that U.S. organizations spent on learning and development was targeted at leadership development ( O’Leonard, 2010 ).

Despite the fact that organizations are increasing their investments in leadership development, there is an emerging consensus that the supply of leadership talent is insufficient to meet the leadership needs of contemporary organizations. According to a survey of 1,100 U.S.-based organizations, 56 per cent of employers report a dearth of leadership talent, and 31 per cent of organizations expect to have a shortage of leaders that will impede performance in the next four years ( Adler & Mills, 2008 ). Likewise, a survey of 13,701 managers and HR professionals across 76 countries found that individuals’ confidence in their leaders declined by 25 per cent from 1999–2007, and that 37 per cent of respondents believe those who hold leadership positions fail to achieve their position’s objectives ( Howard & Wellins, 2009 ). These data allude to an emerging leadership talent crisis where the need and demand for leadership surpass our ability to develop effective leadership talent.

Ironically, this leadership talent crisis is emerging at the same time the pace of scholarly research on leadership development is reaching a historical peak. Conceptual and empirical research on leadership development has proliferated through the publication of a number of books, including the Center for Creative Leadership Handbook of Leadership Development ( Van Velsor, McCauley, & Ruderman, 2010 ), Day and colleagues’ (2009 ) Integrated Approach to Leader Development , and Avolio’s (2005 ) Leadership Development in Balance . Likewise, reviews of the leadership development literature point to rapid growth in the base of scholarly research on leadership development over the past 20 years ( Collins & Holton, 2004 ; Day, 2000 ; Hernez-Broome & Hughes, 2004 ; McCall, 2004 ), and numerous special issues in management and psychology journals have been dedicated to the topic ( DeRue, Sitkin, & Podolny, 2011 ; Pearce, 2007 ; Riggio, 2008 ). All of this scholarly literature is notwithstanding the thousands of popular press books and articles that have been written on the topic.

Indeed, the depth and richness of the existing literature has produced an array of important insights about leadership development in organizations. For example, drawing from experiential learning theories ( Dewey, 1938 ; Kolb, 1984 ), scholars have documented how lived experiences that are novel, of high significance to the organization, and require people to manage change with diverse groups of people and across organizational boundaries are important sources of leadership development ( DeRue & Wellman, 2009 ; McCall & Hollenbeck, 2002 ; McCall, Lombardo, & Morrison, 1988 ; McCauley, Ruderman, Ohlott, & Morrow, 1994 ). Indeed, it was this research that led McCall (2004 , p. 127) to conclude that “the primary source of learning to lead, to the extent that leadership can be learned, is experience.” In addition, scholars have identified an array of personal attributes (e.g., learning orientation, developmental readiness) and situational characteristics (e.g., feedback, coaching, reflection practices) that influence how much leadership development occurs via these lived experiences ( Avolio & Hannah, 2008 ; Alimo-Metcalfe, 1998 ; DeRue & Wellman, 2009 ; Dragoni, Tesluk, Russell, & Oh, 2009 ; Hirst, Mann, Bain, Pirola-Merlo, & Richver, 2004 ; Ting & Scisco, 2006 ). Moving beyond the sources and predictors of leadership development, researchers have also examined a multitude of outcomes associated with leadership development, including but not limited to the development of individuals’ leadership knowledge, skills, abilities, motivations, and identities ( Chan & Drasgow, 2001 ; Day & Harrison, 2007 ; DeRue & Ashford, 2010a ; Mumford, Campion, & Morgeson, 2007 ; Mumford, Zaccaro, Harding, Jacobs, & Fleishman, 2000 ). Altogether, these conceptual articles and empirical studies provide substantial insight into a complex and multifaceted leadership development process, and point to various ways in which individuals and organizations can enhance (and impair) leadership development.

Despite notable progress in our understanding of leadership development, there are at least three reasons why this body of literature has not yielded the insights and breakthroughs that are needed to sufficiently inform and address the emerging leadership talent crisis. First, the existing literature is predominantly focused on individual leader development, at the expense of understanding the evolution of leading-following processes and the construction of leadership relationships and structures in groups and organizations ( DeRue, 2011 ; DeRue & Ashford, 2010a ). This focus on individuals as the target of development may stem from the broader leadership literature, which has traditionally endorsed an individualistic and hierarchical conception of leadership ( Bedeian & Hunt, 2006 ). However, there is an emerging shift toward thinking of leadership as a shared activity or process that anyone can participate in, regardless of their formal position or title ( Charan, 2007 ; Day, Gronn, & Salas, 2004 ; Morgeson, DeRue & Karam, 2010 ; Quinn, 1996 ; Pearce & Conger, 2003 ). In turn, the leadership development literature needs to explain how these collective leadership processes develop and evolve over time.

Second, consistent with the focus on individuals, the existing literature generally endorses a narrow focus on the knowledge, skills, and abilities (KSAs) required for effective leadership ( Mumford, Campion, & Morgeson, 2007 ; Mumford et al., 2000 ). One potential reason for the focus on KSAs is that much of the existing literature on leadership development is framed within the domain of human resource management, which often focuses on the training and transfer of KSAs ( Saks & Belcourt, 2006 ). Another potential reason is that scholars have developed coherent theories and taxonomies of leadership KSAs, and there is clear evidence linking these leadership KSAs to individual leader effectiveness ( Connelly et al., 2000 ; Mumford et al., 2007 ). Only recently have scholars begun to explore a wider range of leadership development outcomes, including individuals’ self-concept and identity ( Day & Harrison, 2007 ; DeRue & Ashford, 2010a ; Lord & Hall, 2005 ), motivations related to leadership ( Barbuto, 2005 ; Chan & Drasgow, 2001 ), and mental models of leadership ( Lord, Brown, Harvey & Hall, 2001 ; Epitropaki & Martin, 2004 ; Lord, Foti, & De Vader, 1984 ). These alternative outcomes are important to understanding leadership development because it is possible that individuals are developing the KSAs necessary for effective leadership, but are choosing not to take on leadership roles because they do not see themselves as leaders, or they are not motivated to lead given the risks associated with it ( Heifetz & Linsky, 2002 ). Although these leadership identities, motivations, and mental models could be the target of leadership development interventions, it is not clear based on the current research how malleable these attributes are, or what types of experiences or interventions would develop them.

Finally, consistent with Avolio’s (2007 ) call for more integrative theory building in the leadership literature, our field lacks a coherent and integrative framework for organizing the existing literature on leadership development. With respect to the emerging leadership talent crisis, this lack of an integrative, organizing framework is limiting progress in two ways. First, without an integrative understanding of the inputs, processes, and outcomes associated with leadership development, organizations are forced to speculate or rely on intuition as to what to develop, how to develop it, where and when it should be developed, and who is ready (or not ready) for development. Second, it remains unclear what the critical knowledge gaps are related to leadership development, and where future research needs to focus in order to help organizations more effectively identify and develop future leadership talent.

Thus, the aim of this chapter is to develop an organizing framework for the inputs, processes, and outcomes associated with leadership development, synthesize key insights from the existing literature, and identify critical knowledge gaps that can serve as the impetus for future research on leadership development. We seek to accomplish these goals, as well as complement and extend prior reviews of this literature ( Brungardt, 1997 ; Day, 2000 ), by first defining leadership development and articulating some of the key assumptions associated with this definition. We then introduce an organizing framework called PREPARE, and use this framework to integrate key insights from the existing literature. We conclude by summarizing an agenda for future research based on the PREPARE framework, with the purpose of extending existing theories of leadership development and advancing our understanding of what individuals and organizations can do to identify and develop leadership talent.

Leadership Development: A Definition

Leadership is a social and mutual influence process where multiple actors engage in leading-following interactions in service of accomplishing a collective goal ( Bass & Bass, 2008 ; Yukl, 2010 ). In his oft-cited review of the leadership development literature, Day (2000 ) distinguishes between two forms of development. Individual leader development focuses on an individual’s capacity to participate in leading-following processes and generally presumes that developing an individual’s leadership KSAs will result in more effective leadership. A key limitation of this perspective is that it does not account for leadership as a complex and interactive process among multiple actors who are both leading and following, or that the relationships that are created and maintained within the social context can have a strong influence on how leadership processes emerge and evolve ( Day & Halpin, 2004 ; DeRue, 2011 ). The second form, leadership development, focuses on developing the capacity of collectives to engage in the leadership process. Whereas leader development focuses on individuals and the development of human capital, leadership development attends to the interpersonal dynamics of leadership and focuses on the development of social capital. Specifically, leadership development refers to building the mutual commitments and interpersonal relationships that are necessary for leading-following processes to unfold effectively within a given social context.

Historically, the existing literature has focused on individual leader development at the expense of understanding and explaining leadership development ( Day, 2000 ; Drath et al., 2008 ; Van Velsor, McCauley, & Ruderman, 2010 ). In fact, because of the dearth of research on leadership development, prior reviews of the existing literature have been forced to acknowledge the importance of leadership development but then go on to narrowly focus on individual leader development (e.g., Day, 2000 ; McCauley, 2008 ). This narrow focus on leader development is unfortunate because both leader and leadership development are necessary but insufficient for understanding and explaining how leadership capacity is developed, especially as organizations embrace more collective and shared models of leadership ( Pearce & Conger, 2003 ).

In the present article, we broaden the definition of leadership development to include both individual and collective forms of development. Specifically, we define leadership development as the process of preparing individuals and collectives to effectively engage in leading-following interactions. Several assumptions are embedded in this definition. First, we assume that both leader and leadership development are essential for enabling more effective leadership processes in organizations. Individuals need the leadership KSAs, motivations, and beliefs necessary to effectively participate in the leading-following process, but effective leading-following interactions also involve the emergence of leader-follower relationships and collective leadership structures. In addition, we assume that leader and leadership development are interdependent. Developmental experiences or interventions designed to promote more effective leadership relationships will also affect individuals’ KSAs, beliefs, and motivations. Likewise, actions taken to enhance individual leadership capabilities will indirectly alter the landscape of leading-following relationships among actors. Therefore, the conceptual model we use to structure our literature review will incorporate both individual leader development and the development of leadership relationships and collective structures.

Our expectation is that the framework developed herein will be used by researchers in several ways. First, as noted above, the framework is purposefully integrative across a range of levels of analysis and developmental approaches, with the intent of motivating scholars to adopt a more integrative approach to studying leadership development. For example, scholars might use the framework to emphasize the intersection of individual leader development with more relational or collective forms of development, or ways in which formal training might complement informal, on-the-job development. Second, researchers can use the framework to conceptualize a broader range of outcomes associated with leadership development. Historically, leadership development research has focused narrowly on the development of individual skills or competencies, but this framework emphasizes a range of individual, relational, and collective outputs of leadership development. Finally, we expect scholars can use the framework to situate their individual studies within a broader nomological network of research on leadership development, which in turn will identify key gaps in the literature and advance the accumulation of knowledge related to leadership development.

PREPARE: An Organizing Framework

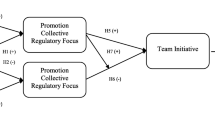

As illustrated in Figure 37.1 , PREPARE is an acronym that refers to the individual components of our organizing framework. The PREPARE framework consists of seven key components: (1) Purpose, (2) Result, (3) Experience, (4) Point of Intervention, (5) Architecture, (6) Reinforcement, and (7) Engagement.

Purpose refers to why an organization is engaging in leadership development: in particular the role that leadership development plays in enabling an organization to achieve its strategic objectives and performance goals. The Result component refers to the desired outcome, what is actually trying to be developed, such as individuals’ cognitive schemas related to leadership (e.g., implicit leadership theory), the affective or relational ties among group members (e.g., trust), or the organizational climate for shared leadership. Experience refers to the mechanism through which leadership development occurs, specifically what experiences (e.g., formal training, on-the-job assignments) will serve as the basis for challenging individuals and/or collectives to improve their leadership capacity. These experiences vary in their formality (e.g., on-the-job assignments, classroom experiences), mode (e.g., direct or vicarious) and content (e.g., the degree of developmental challenge). The Point of Intervention component represents the intended target of leadership development (i.e., who is being developed), and the attributes associated with that target. The target can be at the individual level (e.g., developing an individual’s skills), the relational level (e.g., developing the leading-following relationship among actors), or the collective level (e.g., shared team leadership). Architecture refers to features of the organizational context (e.g., practices, processes, climate) that are designed to facilitate and support leadership development. The Reinforcement components refer to the temporal sequencing of developmental experiences, and the timing of those experiences. Finally, the Engagement component refers to the ways in which individuals and collectives enter, go through, and reflect on the leadership development process.

PREPARE Framework for Leadership Development.

Each of these seven dimensions receives a different level of attention in the existing literature. For example, scholars frequently examine how the organizational architecture (e.g., 360º feedback, mentoring, and coaching programs) supports individual leader development (e.g., Alimo-Metcalfe, 1998 ; Brungardt, 1997 ), but few scholars consider the purpose of leadership development or how leadership development is aligned (or not aligned) with organizational strategy. Likewise, scholars rarely theorize or empirically examine how developmental experiences should be sequenced so that they are reinforcing over time. Our contention is that each of these dimensions is an essential ingredient to successful leadership development, and that the design of effective leadership development systems must address each of these components. Our hope is that the PREPARE framework helps organize key insights from the existing literature in a way that synthesizes what is known about leadership development, highlights questions that need to be addressed in future research, and provides guidance to individuals and organizations looking to improve their leadership talent. In the sections that follow, we review the base of scholarly research for each of the PREPARE dimensions, and identify key knowledge gaps that can serve as the impetus for future research.

Purpose: Aligning Leadership Development and Organizational Strategy

Theories of strategic human resource management explain how different patterns of human resource management (HRM) practices and activities enable organizations to achieve their strategic objectives and goals ( Wright & McMahan, 1992 ; Wright & Snell, 1998 ). Drawing from theories of fit and congruence ( Nadler & Tushman, 1980 ; Venkatraman, 1989 ), these strategic HRM theories emphasize that organizational performance is in part a function of the alignment between HRM practices and the organization’s strategy ( Schuler & Jackson, 1987 ). Indeed, empirical research has established that a key predictor of organizational productivity and performance is the alignment between firm strategy and the configuration of HRM practices ( Delery & Doty, 1996 ; Youndt, Snell, Dean & Lepak, 1996 ).

With respect to leadership development practices, organizations often speculate that alignment between organizational strategy and leadership development practices is important for maximizing the return on investment in leadership development ( Zenger, Ulrich, & Smallwood, 2000 ). For example, in their report on the Top Companies for Leaders , Hewitt & Associates (2009 ) concluded that “...HR leaders and senior management are finding they must rethink leadership selection and development strategies—to better align with organizational goals, cost pressures, and competing resources.” Similarly, in a review of best-practices research on leadership development, McCauley (2008 ) underscored how, in best-practice organizations, leadership development practices are closely tied to the vision, values, and goals of the business, and that leadership development is a core part of the organization’s strategic planning processes. These conclusions are consistent with McCall and Hollenbeck’s (2002 ) contention that global leaders are best developed through challenging experiences and assignments that are tied to the strategic imperatives of the business.

Despite the fact that organizations are emphasizing strategic alignment with leadership development practices, there is currently a lack of scholarly research on the mechanisms through which leadership development can support organizational goals and strategies, or the implications of alignment in terms of return on investments in leadership development. The research on strategic HRM suggests that alignment with organizational strategy will be essential for developing leadership development systems that promote and enhance organizational effectiveness, but research is needed to connect these insights about general HRM practices to leadership development specifically. Currently, the field of leadership development studies lacks a theoretical or empirical basis for explaining how organizations can achieve strategic alignment with leadership development practices, or why strategic alignment enhances the value of leadership development to the organization.

In fact, there are some trends in the leadership development literature that suggest a sort of duality with respect to aligning leadership development with organizational strategy. On the one hand, scholars suggest that an important source of leadership development is having individuals and groups engage in challenging assignments that are directly linked to firm strategy and the future directions of the business ( McCall et al., 1988 ; McCall & Hollenbeck, 2002 ). On the other hand, organizations are increasing outsourcing leadership development by placing employees in challenging, developmental experiences that are outside of the organization and have very little to do with the organization’s strategy (e.g., IBM’s Peace Corps; Colvin, 2009 ). There are likely benefits to both approaches. Strategic alignment should not only enhance employees’ leadership development but also directly contribute to the business needs of the organization. Yet, enabling employees to explore developmental opportunities outside of the core business may also broaden the employee’s perspective and introduce motivational benefits that might not be possible within the context of the core business. Future research that examines the value of strategic alignment in leadership development, and how best to balance developmental experiences that are inside the organization’s core business with experiences outside of the core business, would be particularly noteworthy. This research would go a long way toward helping organizations explain and understand the business returns associated with leadership development.

Result: Identifying the Desired Outcome of Leadership Development

Organizations invest considerable resources into identifying the “holy grail” of leadership competencies that are needed for success in their organization ( Alldredge & Nilan, 2000 ; Intagliata, Ulrich, & Smallwood, 2000 ). As described by Intagliata et al. (2000 , p. 12), “This holy grail, when found, would identify a small set of attributes that successful leaders possess, articulate them in ways that could be transferred across all leaders, and create leadership development experiences to ensure that future leaders possess these attributes.” Indeed, organizations routinely use their leadership competency models not only for leadership development but also for performance management, recruiting and staffing, and succession planning ( Gentry & Leslie, 2007 ; McCauley, 2008 ). The challenge, however, is that it is unclear whether there is such a “holy grail,” or even a coherent set of attributes or competencies that are needed for effective leadership.

Scholarly research on leadership development has considered a range of development outcomes, including leadership KSAs ( Hulin, Henry & Noon, 1990 ; Mumford et al., 2007 ), forms of cognition such as leadership schemas and identities ( Day & Harrison, 2007 ; DeRue, Ashford, & Cotton, 2009 ; Shamir & Eilam, 2005 ), and the motivations associated with taking on leadership roles and responsibilities ( Chan & Drasgow, 2001 ; Kark & Van Dijk, 2007 ). In addition, scholars have looked beyond individual attributes and examined the development and evolution of leader-follower relationships ( DeRue & Ashford, 2010a ; Nahrgang, Morgeson, & Ilies, 2009 ). Although we do not intend to discover the “holy grail” of leadership competencies in this chapter, we can identify three broad themes of development outcomes in the existing literature: behavioral, affective/motivational, and cognitive. Further, each of these themes can be conceptualized at the individual, relational, or collective level of analysis, although most existing research is at the individual level.

Behavioral . We conceptualize behavioral outcomes in leadership development as the acquisition of leadership KSAs that are necessary for the performance of specific leadership behaviors, or positive changes in the performance of actual leadership behaviors. In the current literature, leadership development scholars have considered a wide range of these behavioral outcomes. One influential article in this domain is Mumford et al.’s (2007 ) leadership skills strataplex. In this article, the authors identify four distinct categories of leadership skill requirements: cognitive skills, interpersonal skills, business skills, and strategic skills. Then, in a sample of 1023 professional employees in an international agency of the U.S. government, the authors find empirical support for the four distinct categories of leadership skill requirements, and show that different categories of leadership skill requirements emerge at different hierarchical levels of organizations. For example, basic cognitive skills are required across all hierarchical levels, but strategic skills become important only once employees reach senior-level positions.

Moving beyond the acquisition of leadership skills, leadership scholars have also examined changes in the performance of actual leadership behaviors. For example, Barling, Weber, and Kelloway (1996 ) conducted a field experiment of 20 managers randomly assigned to either a control condition or a leadership training condition. In the training group, managers received a one-day training seminar on transformational leadership, followed by four booster training sessions on a monthly basis. The control group received no such training. Drawing upon subordinates’ perceptions of transformational leadership behaviors, results showed that participants in the training group improved their performance of transformational leadership behaviors more so than participants in the control group. In a similar study design, Dvir and colleagues (2002 ) examined the impact of transformational leadership training on follower development and performance. In a sample of 54 military leaders, their results establish that transformational leadership training can increase leaders’ display of transformational leadership behaviors, which in turn have a positive effect on follower motivation, morality, empowerment, and performance.

Affect/Motivational . Most of the existing research has conceptualized and empirically studied leadership development in terms of behavioral outcomes, but scholars have recently begun to examine how individuals’ affective states and their motivations related to leadership influence how they engage in, go through, and process leadership experiences. For example, individuals’ positive and negative affective states explain not only their leadership effectiveness, but also how leaders influence followers’ affect and behavior ( Bono & Ilies, 2006 ; Damen, Van Knippenberg, & Van Knippenberg, 2008 ; Ilies, Judge, & Wagner, 2006 ). Similarly, emotional intelligence, or the ability to understand and manage moods and emotions in the self and others ( Mayer, Salovey, Caruso, & Sitarenios, 2001 ), can contribute to effective leadership in organizations ( George, 2000 ; Prati, Douglas, Ferris, Ammeter, & Buckley, 2003 ). In terms of motivation, scholars have suggested and found some empirical support for the notion that individuals have different levels of motivation for leadership, and that these motivations can impact participation in leadership roles and leadership potential ( Chan & Drasgow, 2001 ; Kark & van Dijk, 2007 ).

However, in contrast to behavioral outcomes, there is very little empirical research on how individuals or collectives develop the affective or motivational attributes that promote effective leadership. Rather, most of the existing research focuses on how these affective and motivational attributes influence the leadership process or the individual’s effectiveness as a leader (e.g., Atwater, Dionne, Avolio, Camobreco, & Lau, 1999 ; Chemers, Watson, & May, 2000 ). The antecedents to these attributes or the processes through which these attributes are developed generally remain a mystery. Notable exceptions include Chan and Drasgow’s (2001 ) study of Singaporean military cadets, where they find that personality, cultural values such as collectivism and individualism, and prior leadership experience predict whether individuals are motivated to take on leadership roles and responsibilities. Likewise, Boyce, Zaccaro, and Wisecarver (2010 ), in their study of junior-military cadets, find that individuals who have a mastery and learning orientation are more motivated than people without this orientation to engage in leadership development activities, and in addition, are more skilled at self-regulatory, learning processes. Yet, the developmental implications of these studies are unclear given that attributes such as personality and values can be fixed properties of a person ( Costa & McCrae, 1994 ; Schwartz, 1994 ). Another exception is Shefy and Sadler-Smith’s (2006 ) case study of a management development program implemented in a technology company, whereby focusing on non-Western principles of human development (e.g., harmony and balance), the program enhanced individuals’ emotional awareness and interpersonal sensitivity.

Notwithstanding these few exceptions, there is a considerable need for research on the development of the affective and motivational attributes that enable individuals to effectively participate in the leadership process. For example, affective events theory ( Weiss & Cropanzano, 1996 ) explains how work events interact with dispositional characteristics and situational factors to influence individuals’ affective states. This focus on event-level phenomena is consistent with the notion that discrete work events and experiences are the primary source of leadership development ( McCall, 2004 ), yet these two literatures have yet to be integrated. Future research that explains how work events and experiences influence the development of particular affective states, and how these affective states enable more effective leadership and leadership development processes, would help integrate and extend theories of affect and leadership development. Likewise, a fundamentally important question that needs to be explored further is why some people are more motivated than others to take on leadership roles and responsibilities, even when they are not designated as a formal leader. This research needs to move beyond a focus on stable individuals’ differences, and consider how the social and organizational context enables (or constrains) individual motivation for leadership. In particular, this research could build on prior theories of the rewards and risks associated with leadership ( Heifetz & Linsky, 2002 ) to understand how people process, cognitively and emotionally, the rewards and risks of assuming leadership roles and responsibilities in different group and organizational contexts.

Cognitive . Cognitive outcomes refer to the mental models and structures that individuals and collectives rely on to participate in and carry out leadership processes. In this sense, individuals and collectives develop their capacity for effective leadership by expanding or changing their conceptual models and mental structures of what it means to lead, the way in which leading-following processes unfold, and/or their conception of themselves as leaders and followers. Indeed, a commonly espoused purpose of using multi-rater feedback for leadership development is to create self-awareness and stimulate reflection related to what leadership means in a given setting and to expand people’s conceptions of their roles as leaders ( Yammarino & Atwater, 1993 ). Developing these cognitive models and mental structures are important because they impact how people engage in leadership processes ( Shamir & Eilam, 2005 ).

In the existing literature, there are at least three cognitive outcomes that seem particularly important for leadership development, especially as organizations embrace collective and shared forms of leadership. First, an individual’s self-concept or identity as a leader is important for determining how that person will engage in the leadership process ( Day & Harrison, 2007 ; DeRue & Ashford, 2010a ; DeRue, Ashford & Cotton, 2009 ; Hall, 2004 ; Shamir & Eilam, 2005 ). Developmental experiences allow individuals to create, modify, and adapt their identities as leaders by “trying on” different possible self-concepts ( Ibarra, 1999 ) and engaging in the identity work that is necessary to clarify one’s self-concept ( Kreiner, Hollensbe, & Sheep, 2006 ). Importantly, this identity development is not limited to the individual level, as leadership development can help individuals construct leadership identities at the relational and collective levels of analysis, which then become the basis for the formation of effective leading-following relationships ( DeRue & Ashford, 2010a ). In addition, with the increasing interest in ethical leadership and moral psychology ( Aquino & Reed, 2002 ; Mayer, Kuenzi, Greenbaum, Bardes, & Salvador, 2009 ), research on the development of individual and collective levels of moral identity may prove to be particularly important as leadership development outcomes.

Another potentially important cognitive outcome for leadership development is individuals’ implicit theories of leadership. Implicit leadership theories (ILTs) refer to people’s cognitive schemas for what personal attributes and behavioral tendencies make for an effective leader, and these ILTs can have a significant impact on individuals’ perceptions of who is (and is not) a leader in a given context ( Epitropaki & Martin, 2004 ; Lord, Foti, & De Vader, 1984 ; Rush, Thomas, & Lord, 1977 ). There is some research evidence supporting the idea that these ILTs emerge as a result of cultural background ( House, Javidan, Hanges, & Dorfman, 2002 ), media influence ( Holmberg & Akerblom, 2001 ), and life experience ( Keller, 2003 ). However, much more research is needed to clarify the origin of these beliefs about prototypical leaders, as well as what organizations can do to modify these beliefs. It is quite possible that many people choose not to take on leadership roles because they perceive a misfit between their own self-concept and what they believe to be prototypical of an effective leader. However, it is also possible that organizations can change these perceptions and create a fit between people’s self-concept and their ILT, thereby engendering a greater propensity to step up and take on leadership.

Finally, scholars are beginning to suggest that individuals not only have implicit theories about who is prototypical of an effective leader, but that individuals also have implicit theories about how leadership is structured in groups. For example, DeRue and Ashford (2010a ) proposed the concept of a leadership-structure schema, which refers to whether individuals conceptualize leadership as zero-sum and reserved for a single individual within a group (often the designated leader), or whether leadership can be shared among multiple group members. Following up on this proposition, there is emerging empirical evidence suggesting that not only do individuals possess different leadership-structure schemas, but also that these schemas are malleable and can be developed ( Hinrichs, Carson, Li, & Porter, 2011 ; Wellman, Ashford, DeRue, & Sanchez-Burks, 2011 ). Future research that examines the developmental interventions that alter the leadership-structure schemas of individuals and collectives, and the implications for group process and performance, would be particularly important for promoting more shared leadership in organizations.

In addition to behavioral, affective/motivational, and cognitive development outcomes, leadership development scholars have also examined changes in overall leadership performance or leadership emergence (e.g., Atwater, Dionne, Avolio, Camobreco, & Lau, 1999 ). Given that it is rare for empirical studies to model changes in leadership behavior or performance, these studies offer valuable insight into the predictors of leadership development. However, because they focus on overall performance changes and rarely experimentally manipulate the developmental intervention, these studies offer less insight into what is actually being developed or causing the observed change in leadership performance. On the one hand, it might be that individuals are developing new leadership skills or motivations. On the other hand, it is also possible that the context is changing in ways that enable individuals’ to engage in more effective leadership behavior, but that no meaningful development is occurring. For future research, we recommend scholars assess change over time in specific behavioral, affective/motivational, and/or cognitive outcomes, which will provide more insight into the underlying mechanisms explaining improvements in leadership performance or emergence.

Experience: Developing Leadership through Lived Experience

Drawing on experiential learning theories ( Dewey, 1938 ; Knowles, 1970 ; Kolb, 1984 ), scholars at the Center for Creative Leadership conducted the early research on the role of experience in leadership development ( McCall et al., 1988 ). This research then spawned a multitude of follow-up studies exploring a range of leadership development experiences, and there is now considerable consensus in the existing literature that the primary source of leadership development is experience ( McCall, 2004 ; Ohlott, 2004 ; Van Velsor & Drath, 2004 ). As Mumford and colleagues (2000 ) note, without appropriate developmental experience, even the most intelligent and motivated individuals are unlikely to be effective leaders.

The existing research on experience-based leadership development spans across a wide range of different types of experiences, including informal on-the-job assignments ( McCall et al., 1988 ), coaching and mentoring programs ( Ting & Sciscio, 2006 ), and formal training programs ( Burke & Day, 1986 ). A common assumption in the existing literature is that 70 per cent of leadership development occurs via on-the-job assignments, 20 per cent through working with and learning from other people (e.g., learning from bosses or coworkers), and 10 per cent through formal programs such as training, mentoring, or coaching programs ( McCall et al., 1988 ; Robinson & Wick, 1992 ). Despite the popularity of this assumption, there are four fundamental problems with framing developmental experiences in this way. First and foremost, there is actually no empirical evidence supporting this assumption, yet scholars and practitioners frequently quote it as if it is fact. Second, as McCall (2010 ) appropriately points out, this assumption is misleading because it suggests informal, on-the-job experiences, learning from other people, and formal programs are independent. Yet, these different forms of experience can occur in parallel, and it is possible (and likely optimal) that learning in one form of experience can complement and build on learning in another form of experience. Third, it is inconsistent with the fact that a large portion of organizational investments are directed at formal leadership development programs ( O’Leonard, 2010 ). It is certainly possible that organizations are misguided in their focus on and deployment of these programs ( Conger & Toegel, 2003 ), but we are not ready to condemn formal programs given the lack of empirical evidence. Finally, it is possible that the “70:20:10” assumption leads organizations to prioritize informal, on-the-job experience over all other forms of developmental experiences, which some scholars argue allows leadership development to become a “haphazard process” ( Conger, 1993 , p. 46) without sufficient notice to intentionality, accountability, and formal evaluation ( Day, 2000 ).

We offer an integrative framework for conceptualizing the different forms of developmental experience, including both formal and informal developmental experiences. Specifically, we propose that developmental experiences are best described and understood in terms of three dimensions: formality, mode, and content.

Formality . The formality dimension ranges from formal to informal. Formal developmental experiences are activities designed with the intended purpose of leadership development, which would include leadership training programs and interventions. In contrast, informal developmental experiences occur within the normal context of everyday life and are often not designed for the specific purpose of leadership development. Another way the formal versus informal distinction appears in the literature is when Avolio and colleagues discuss planned and unplanned events that serve as “developmental triggers” ( Avolio, 2004 ; Avolio & Hannah, 2008 ). These trigger events are experiences that prompt a person to focus attention on the need to learn and develop, but as Avolio and his colleagues propose, formal training that is planned and informal experiences that are unplanned can both serve as developmental triggers.

One assumed benefit of formal developmental experiences is that they allow individuals to spend time away from the workplace, where they are free to challenge existing ways of thinking and reflect more deeply on the lessons of experience ( Fulmer, 1997 ). Indeed, meta-analyses by Burke and Day (1986 ) and Collins and Holton (2004 ) suggest that formal leadership programs have a positive impact on employees’ acquisition of new knowledge, behavior change, and performance. However, as noted by Collins and Holton (2004 ), formal development programs have a stronger, positive effect on knowledge outcomes in comparison to behavior or performance outcomes. One reason for this differential effect could be that program participants acquire new knowledge and skills, but then encounter barriers to transferring those lessons to their actual jobs ( Belling, James, & Ladkin, 2004 ).