- If you are writing in a new discipline, you should always make sure to ask about conventions and expectations for introductions, just as you would for any other aspect of the essay. For example, while it may be acceptable to write a two-paragraph (or longer) introduction for your papers in some courses, instructors in other disciplines, such as those in some Government courses, may expect a shorter introduction that includes a preview of the argument that will follow.

- In some disciplines (Government, Economics, and others), it’s common to offer an overview in the introduction of what points you will make in your essay. In other disciplines, you will not be expected to provide this overview in your introduction.

- Avoid writing a very general opening sentence. While it may be true that “Since the dawn of time, people have been telling love stories,” it won’t help you explain what’s interesting about your topic.

- Avoid writing a “funnel” introduction in which you begin with a very broad statement about a topic and move to a narrow statement about that topic. Broad generalizations about a topic will not add to your readers’ understanding of your specific essay topic.

- Avoid beginning with a dictionary definition of a term or concept you will be writing about. If the concept is complicated or unfamiliar to your readers, you will need to define it in detail later in your essay. If it’s not complicated, you can assume your readers already know the definition.

- Avoid offering too much detail in your introduction that a reader could better understand later in the paper.

- picture_as_pdf Introductions

What this handout is about

This handout will define what an argument is and explain why you need one in most of your academic essays.

Arguments are everywhere

You may be surprised to hear that the word “argument” does not have to be written anywhere in your assignment for it to be an important part of your task. In fact, making an argument—expressing a point of view on a subject and supporting it with evidence—is often the aim of academic writing. Your instructors may assume that you know this and thus may not explain the importance of arguments in class.

Most material you learn in college is or has been debated by someone, somewhere, at some time. Even when the material you read or hear is presented as a simple fact, it may actually be one person’s interpretation of a set of information. Instructors may call on you to examine that interpretation and defend it, refute it, or offer some new view of your own. In writing assignments, you will almost always need to do more than just summarize information that you have gathered or regurgitate facts that have been discussed in class. You will need to develop a point of view on or interpretation of that material and provide evidence for your position.

Consider an example. For nearly 2000 years, educated people in many Western cultures believed that bloodletting—deliberately causing a sick person to lose blood—was the most effective treatment for a variety of illnesses. The claim that bloodletting is beneficial to human health was not widely questioned until the 1800s, and some physicians continued to recommend bloodletting as late as the 1920s. Medical practices have now changed because some people began to doubt the effectiveness of bloodletting; these people argued against it and provided convincing evidence. Human knowledge grows out of such differences of opinion, and scholars like your instructors spend their lives engaged in debate over what claims may be counted as accurate in their fields. In their courses, they want you to engage in similar kinds of critical thinking and debate.

Argumentation is not just what your instructors do. We all use argumentation on a daily basis, and you probably already have some skill at crafting an argument. The more you improve your skills in this area, the better you will be at thinking critically, reasoning, making choices, and weighing evidence.

Making a claim

What is an argument? In academic writing, an argument is usually a main idea, often called a “claim” or “thesis statement,” backed up with evidence that supports the idea. In the majority of college papers, you will need to make some sort of claim and use evidence to support it, and your ability to do this well will separate your papers from those of students who see assignments as mere accumulations of fact and detail. In other words, gone are the happy days of being given a “topic” about which you can write anything. It is time to stake out a position and prove why it is a good position for a thinking person to hold. See our handout on thesis statements .

Claims can be as simple as “Protons are positively charged and electrons are negatively charged,” with evidence such as, “In this experiment, protons and electrons acted in such and such a way.” Claims can also be as complex as “Genre is the most important element to the contract of expectations between filmmaker and audience,” using reasoning and evidence such as, “defying genre expectations can create a complete apocalypse of story form and content, leaving us stranded in a sort of genre-less abyss.” In either case, the rest of your paper will detail the reasoning and evidence that have led you to believe that your position is best.

When beginning to write a paper, ask yourself, “What is my point?” For example, the point of this handout is to help you become a better writer, and we are arguing that an important step in the process of writing effective arguments is understanding the concept of argumentation. If your papers do not have a main point, they cannot be arguing for anything. Asking yourself what your point is can help you avoid a mere “information dump.” Consider this: your instructors probably know a lot more than you do about your subject matter. Why, then, would you want to provide them with material they already know? Instructors are usually looking for two things:

- Proof that you understand the material

- A demonstration of your ability to use or apply the material in ways that go beyond what you have read or heard.

This second part can be done in many ways: you can critique the material, apply it to something else, or even just explain it in a different way. In order to succeed at this second step, though, you must have a particular point to argue.

Arguments in academic writing are usually complex and take time to develop. Your argument will need to be more than a simple or obvious statement such as “Frank Lloyd Wright was a great architect.” Such a statement might capture your initial impressions of Wright as you have studied him in class; however, you need to look deeper and express specifically what caused that “greatness.” Your instructor will probably expect something more complicated, such as “Frank Lloyd Wright’s architecture combines elements of European modernism, Asian aesthetic form, and locally found materials to create a unique new style,” or “There are many strong similarities between Wright’s building designs and those of his mother, which suggests that he may have borrowed some of her ideas.” To develop your argument, you would then define your terms and prove your claim with evidence from Wright’s drawings and buildings and those of the other architects you mentioned.

Do not stop with having a point. You have to back up your point with evidence. The strength of your evidence, and your use of it, can make or break your argument. See our handout on evidence . You already have the natural inclination for this type of thinking, if not in an academic setting. Think about how you talked your parents into letting you borrow the family car. Did you present them with lots of instances of your past trustworthiness? Did you make them feel guilty because your friends’ parents all let them drive? Did you whine until they just wanted you to shut up? Did you look up statistics on teen driving and use them to show how you didn’t fit the dangerous-driver profile? These are all types of argumentation, and they exist in academia in similar forms.

Every field has slightly different requirements for acceptable evidence, so familiarize yourself with some arguments from within that field instead of just applying whatever evidence you like best. Pay attention to your textbooks and your instructor’s lectures. What types of argument and evidence are they using? The type of evidence that sways an English instructor may not work to convince a sociology instructor. Find out what counts as proof that something is true in that field. Is it statistics, a logical development of points, something from the object being discussed (art work, text, culture, or atom), the way something works, or some combination of more than one of these things?

Be consistent with your evidence. Unlike negotiating for the use of your parents’ car, a college paper is not the place for an all-out blitz of every type of argument. You can often use more than one type of evidence within a paper, but make sure that within each section you are providing the reader with evidence appropriate to each claim. So, if you start a paragraph or section with a statement like “Putting the student seating area closer to the basketball court will raise player performance,” do not follow with your evidence on how much more money the university could raise by letting more students go to games for free. Information about how fan support raises player morale, which then results in better play, would be a better follow-up. Your next section could offer clear reasons why undergraduates have as much or more right to attend an undergraduate event as wealthy alumni—but this information would not go in the same section as the fan support stuff. You cannot convince a confused person, so keep things tidy and ordered.

Counterargument

One way to strengthen your argument and show that you have a deep understanding of the issue you are discussing is to anticipate and address counterarguments or objections. By considering what someone who disagrees with your position might have to say about your argument, you show that you have thought things through, and you dispose of some of the reasons your audience might have for not accepting your argument. Recall our discussion of student seating in the Dean Dome. To make the most effective argument possible, you should consider not only what students would say about seating but also what alumni who have paid a lot to get good seats might say.

You can generate counterarguments by asking yourself how someone who disagrees with you might respond to each of the points you’ve made or your position as a whole. If you can’t immediately imagine another position, here are some strategies to try:

- Do some research. It may seem to you that no one could possibly disagree with the position you are arguing, but someone probably has. For example, some people argue that a hotdog is a sandwich. If you are making an argument concerning, for example, the characteristics of an exceptional sandwich, you might want to see what some of these people have to say.

- Talk with a friend or with your teacher. Another person may be able to imagine counterarguments that haven’t occurred to you.

- Consider your conclusion or claim and the premises of your argument and imagine someone who denies each of them. For example, if you argued, “Cats make the best pets. This is because they are clean and independent,” you might imagine someone saying, “Cats do not make the best pets. They are dirty and needy.”

Once you have thought up some counterarguments, consider how you will respond to them—will you concede that your opponent has a point but explain why your audience should nonetheless accept your argument? Will you reject the counterargument and explain why it is mistaken? Either way, you will want to leave your reader with a sense that your argument is stronger than opposing arguments.

When you are summarizing opposing arguments, be charitable. Present each argument fairly and objectively, rather than trying to make it look foolish. You want to show that you have considered the many sides of the issue. If you simply attack or caricature your opponent (also referred to as presenting a “straw man”), you suggest that your argument is only capable of defeating an extremely weak adversary, which may undermine your argument rather than enhance it.

It is usually better to consider one or two serious counterarguments in some depth, rather than to give a long but superficial list of many different counterarguments and replies.

Be sure that your reply is consistent with your original argument. If considering a counterargument changes your position, you will need to go back and revise your original argument accordingly.

Audience is a very important consideration in argument. Take a look at our handout on audience . A lifetime of dealing with your family members has helped you figure out which arguments work best to persuade each of them. Maybe whining works with one parent, but the other will only accept cold, hard statistics. Your kid brother may listen only to the sound of money in his palm. It’s usually wise to think of your audience in an academic setting as someone who is perfectly smart but who doesn’t necessarily agree with you. You are not just expressing your opinion in an argument (“It’s true because I said so”), and in most cases your audience will know something about the subject at hand—so you will need sturdy proof. At the same time, do not think of your audience as capable of reading your mind. You have to come out and state both your claim and your evidence clearly. Do not assume that because the instructor knows the material, he or she understands what part of it you are using, what you think about it, and why you have taken the position you’ve chosen.

Critical reading

Critical reading is a big part of understanding argument. Although some of the material you read will be very persuasive, do not fall under the spell of the printed word as authority. Very few of your instructors think of the texts they assign as the last word on the subject. Remember that the author of every text has an agenda, something that he or she wants you to believe. This is OK—everything is written from someone’s perspective—but it’s a good thing to be aware of. For more information on objectivity and bias and on reading sources carefully, read our handouts on evaluating print sources and reading to write .

Take notes either in the margins of your source (if you are using a photocopy or your own book) or on a separate sheet as you read. Put away that highlighter! Simply highlighting a text is good for memorizing the main ideas in that text—it does not encourage critical reading. Part of your goal as a reader should be to put the author’s ideas in your own words. Then you can stop thinking of these ideas as facts and start thinking of them as arguments.

When you read, ask yourself questions like “What is the author trying to prove?” and “What is the author assuming I will agree with?” Do you agree with the author? Does the author adequately defend her argument? What kind of proof does she use? Is there something she leaves out that you would put in? Does putting it in hurt her argument? As you get used to reading critically, you will start to see the sometimes hidden agendas of other writers, and you can use this skill to improve your own ability to craft effective arguments.

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Anson, Chris M., and Robert A. Schwegler. 2010. The Longman Handbook for Writers and Readers , 6th ed. New York: Longman.

Booth, Wayne C., Gregory G. Colomb, Joseph M. Williams, Joseph Bizup, and William T. FitzGerald. 2016. The Craft of Research , 4th ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Ede, Lisa. 2004. Work in Progress: A Guide to Academic Writing and Revising , 6th ed. Boston: Bedford/St Martin’s.

Gage, John T. 2005. The Shape of Reason: Argumentative Writing in College , 4th ed. New York: Longman.

Lunsford, Andrea A., and John J. Ruszkiewicz. 2016. Everything’s an Argument , 7th ed. Boston: Bedford/St Martin’s.

Rosen, Leonard J., and Laurence Behrens. 2003. The Allyn & Bacon Handbook , 5th ed. New York: Longman.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

How to Write an Explanatory Essay: Comprehensive Guide with Examples

What Is an Explanatory Essay: Definition

Have you ever been tasked with explaining a complex topic to someone without prior knowledge? It can be challenging to break down complex ideas into simple terms that are easy to understand. That's where explanatory writing comes in! An explanatory essay, also known as an expository essay, is a type of academic writing that aims to explain a particular topic or concept clearly and concisely. These essays are often used in academic settings but can also be found in newspapers, magazines, and online publications.

For example, if you were asked to explain how a car engine works, you would need to provide a step-by-step explanation of the different parts of the engine and how they work together to make the car move. Or, if you were asked to explain the process of photosynthesis, you would need to explain how plants use sunlight, water, and carbon dioxide to create energy.

When wondering - 'what is an explanatory essay?', remember that the goal of an explanatory paper is to provide the reader with a better understanding of the topic at hand. Unlike an opinion essay , this type of paper does not argue for or against a particular viewpoint but rather presents information neutrally and objectively. By the end of the essay, the reader should clearly understand the topic and be able to explain it to others in their own words.

Also, there is no set number of paragraphs in an explanatory essay, as it can vary depending on the length and complexity of the topic. However, when wondering - 'how many paragraphs in an explanatory essay?', know that a typical example of explanatory writing will have an introduction, body paragraphs, and a conclusion.

However, some essays may have more or fewer body paragraphs, depending on the topic and the writer's preference. Ultimately, an explanatory essay format aims to provide a clear and thorough explanation of the topic, using as many paragraphs as necessary.

.webp)

30 Interesting Explanatory Essay Topics

Now that we have defined what is explanatory essay, the next step is choosing a good explanatory topic. A well-chosen topic is interesting and relevant to your audience while also being something you are knowledgeable about and can provide valuable insights on. By selecting a topic that is too broad or too narrow, you run the risk of either overwhelming your audience with too much information or failing to provide enough substance to fully explain the topic. Additionally, choosing a topic that is too controversial or biased can lead to difficulty in presenting information objectively and neutrally. By choosing a good explanatory topic, you can ensure that your essay is well-informed, engaging, and effective in communicating your ideas to your audience.

Here are 30 creative explanatory essay topics by our admission essay service to consider:

- The Impact of Social Media on Modern Communication

- Exploring the Rise of Renewable Energy Sources Worldwide

- The Role of Genetics in Personalizing Medicine

- How Blockchain Technology is Transforming Finance

- The Influence of Globalization on Local Cultures

- The Science Behind the Human Body’s Circadian Rhythms

- Understanding the Causes and Effects of Global Warming

- The Evolution of Artificial Intelligence and Its Future

- The Psychological Effects of Social Isolation

- The Mechanisms of Dreaming: What Happens While We Sleep?

- The History and Cultural Significance of Coffee

- How Does the Stock Market Work? An Introductory Guide

- The Importance of Bees in Ecosystem Maintenance

- Exploring the Various Forms of Government Around the World

- The Process of DNA Replication and Its Importance

- How Personal Finance Trends Are Shaping the Future of Banking

- The Effects of Music on Human Emotion and Brain Function

- Understanding Climate Change: Causes, Effects, and Solutions

- The Role of Antioxidants in Human Health

- The History of the Internet and Its Impact on Communication

- How 3D Printing is Revolutionizing Manufacturing

- The Significance of Water Conservation in the 21st Century

- The Psychological Impact of Advertising on Consumer Behavior

- The Importance of Vaccinations in Public Health

- How Autonomous Vehicles Will Change the Future of Transportation

- Exploring the Concept of Minimalism and Its Benefits

- The Role of Robotics in Healthcare

- The Economic Impact of Tourism in Developing Countries

- How Urban Farming is Helping to Solve Food Security Issues

- The Impact of Cultural Diversity on Workplace Dynamics

How to Start an Explanatory Essay: Important Steps

Starting an explanatory essay can be challenging, especially if you are unsure where to begin. However, by following a few simple steps, you can effectively kick-start your writing process and produce a clear and concise essay. Here are some tips and examples from our term paper writing services on how to start an explanatory essay:

- Choose an engaging topic : Your topic should be interesting, relevant, and meaningful to your audience. For example, if you're writing about climate change, you might focus on a specific aspect of the issue, such as the effects of rising sea levels on coastal communities.

- Conduct research : Gather as much information as possible on your topic. This may involve reading scholarly articles, conducting interviews, or analyzing data. For example, if you're writing about the benefits of mindfulness meditation, you might research the psychological and physical benefits of the practice.

- Develop an outline : Creating an outline will help you logically organize your explanatory essay structure. For example, you might organize your essay on the benefits of mindfulness meditation by discussing its effects on mental health, physical health, and productivity.

- Provide clear explanations: When writing an explanatory article, it's important to explain complex concepts clearly and concisely. Use simple language and avoid technical jargon. For example, if you're explaining the process of photosynthesis, you might use diagrams and visual aids to help illustrate your points.

- Use evidence to support your claims : Use evidence from reputable sources to support your claims and arguments. This will help to build credibility and persuade your readers. For example, if you're writing about the benefits of exercise, you might cite studies that demonstrate its positive effects on mental health and cognitive function.

By following these tips and examples, you can effectively start your expository essays and produce a well-structured, informative, and engaging piece of writing.

Do You Need a Perfect Essay?

To get a high-quality piece that meets your strict deadlines, seek out the help of our professional paper writers

Explanatory Essay Outline

As mentioned above, it's important to create an explanatory essay outline to effectively organize your ideas and ensure that your essay is well-structured and easy to follow. An outline helps you organize your thoughts and ideas logically and systematically, ensuring that you cover all the key points related to your topic. It also helps you identify gaps in your research or argument and allows you to easily revise and edit your essay. In this way, an outline can greatly improve the overall quality and effectiveness of your explanatory essay.

Explanatory Essay Introduction

Here are some tips from our ' do my homework ' service to create a good explanatory essay introduction that effectively engages your readers and sets the stage for the entire essay:

- Start with a hook: Begin your introduction with an attention-grabbing statement or question that draws your readers in. For example, you might start your essay on the benefits of exercise with a statistic on how many Americans suffer from obesity.

- Provide context: Give your readers some background information on the topic you'll be discussing. This helps to set the stage and ensures that your readers understand the importance of the topic. For example, you might explain the rise of obesity rates in the United States over the past few decades.

- State your thesis: A good explanatory thesis example should be clear, concise, and focused. It should state the main argument or point of your essay. For example, you might state, ' Regular exercise is crucial to maintaining a healthy weight and reducing the risk of chronic diseases.'

- Preview your main points: Give your readers an idea of what to expect in the body of your essay by previewing your main points. For example, you might explain that you'll be discussing the benefits of exercise for mental health, physical health, and longevity.

- Keep it concise: Your introduction should be brief and to the point. Avoid getting bogged down in too much detail or providing too much background information. A good rule of thumb is to keep your introduction to one or two paragraphs.

The Body Paragraphs

By following the following tips, you can create well-organized, evidence-based explanation essay body paragraphs that effectively support your thesis statement.

- Use credible sources: When providing evidence to support your arguments, use credible sources such as peer-reviewed academic journals or reputable news outlets. For example, if you're writing about the benefits of a plant-based diet, you might cite a study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

- Organize your paragraphs logically: Each body paragraph should focus on a specific aspect or argument related to your topic. Organize your paragraphs logically so that each one builds on the previous one. For example, if you're writing about the causes of climate change, you might organize your paragraphs to focus on human activity, natural causes, and the effects of climate change.

- Use transitional phrases: Use transitional phrases to help your readers follow the flow of your ideas. For example, you might use phrases such as 'in addition,' 'furthermore,' or 'on the other hand' to indicate a shift in your argument.

- Provide analysis: Don't just present evidence; provide analysis and interpretation of the evidence. For example, if you're writing about the benefits of early childhood education, you might analyze the long-term effects on academic achievement and future earnings.

- Summarize your main points: End each body paragraph with a sentence that summarizes the main point or argument you've made. This helps to reinforce your thesis statement and keep your essay organized. For example, you might end a paragraph on the benefits of exercise by stating, 'Regular exercise has been shown to improve mental and physical health, making it a crucial aspect of a healthy lifestyle.'

Explanatory Essay Conclusion

Here are some unique tips on how to write an explanatory essay conclusion that leaves a lasting impression on your readers.

.webp)

- Offer a solution or recommendation: Instead of summarizing your main points, offer suggestions based on the information you've presented. This can help to make your essay more impactful and leave a lasting impression on your readers. For example, if you're writing about the effects of pollution on the environment, you might recommend using more eco-friendly products or investing in renewable energy sources.

- Emphasize the importance of your topic: Use your concluding statement to emphasize the importance of your topic and why it's relevant to your readers. This can help to inspire action or change. For example, suppose you're writing about the benefits of volunteering. In that case, you might emphasize how volunteering helps others and has personal benefits such as improved mental health and a sense of purpose.

- End with a powerful quote or statement: End your explanatory essay conclusion with a powerful quote or statement that reinforces your main point or leaves a lasting impression on your readers. For example, if you're writing about the importance of education, you might end your essay with a quote from Nelson Mandela, such as, 'Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world.'

Explanatory Essay Example

Here is an example of an explanatory essay:

Explanatory Essay Example:

Importance of Basketball

Final Thoughts

Now you understand whats an explanatory essay. However, if you're still feeling overwhelmed or unsure about writing an explanatory essay, don't worry. Our team of experienced writers is here to provide you with top-notch academic assistance tailored to your specific needs. Whether you need to explain what is an appendix in your definition essay or rewrite essay in five paragraphs, we've got you covered! With our professional help, you can ensure that your essay is well-researched, well-written, and meets all the academic requirements.

And if you'd rather have a professional craft flawless explanatory essay examples, know that our friendly team is dedicated to helping you succeed in your academic pursuits. So why not take the stress out of writing and let us help you achieve the academic success you deserve? Contact us today with your ' write paper for me ' request, and we will support you every step of the way.

Tired of Struggling to Put Your Thoughts into Words?

Say goodbye to stress and hello to A+ grades with our top-notch academic writing services.

Related Articles

.webp)

Choose Your Test

Sat / act prep online guides and tips, 3 strong argumentative essay examples, analyzed.

General Education

Need to defend your opinion on an issue? Argumentative essays are one of the most popular types of essays you’ll write in school. They combine persuasive arguments with fact-based research, and, when done well, can be powerful tools for making someone agree with your point of view. If you’re struggling to write an argumentative essay or just want to learn more about them, seeing examples can be a big help.

After giving an overview of this type of essay, we provide three argumentative essay examples. After each essay, we explain in-depth how the essay was structured, what worked, and where the essay could be improved. We end with tips for making your own argumentative essay as strong as possible.

What Is an Argumentative Essay?

An argumentative essay is an essay that uses evidence and facts to support the claim it’s making. Its purpose is to persuade the reader to agree with the argument being made.

A good argumentative essay will use facts and evidence to support the argument, rather than just the author’s thoughts and opinions. For example, say you wanted to write an argumentative essay stating that Charleston, SC is a great destination for families. You couldn’t just say that it’s a great place because you took your family there and enjoyed it. For it to be an argumentative essay, you need to have facts and data to support your argument, such as the number of child-friendly attractions in Charleston, special deals you can get with kids, and surveys of people who visited Charleston as a family and enjoyed it. The first argument is based entirely on feelings, whereas the second is based on evidence that can be proven.

The standard five paragraph format is common, but not required, for argumentative essays. These essays typically follow one of two formats: the Toulmin model or the Rogerian model.

- The Toulmin model is the most common. It begins with an introduction, follows with a thesis/claim, and gives data and evidence to support that claim. This style of essay also includes rebuttals of counterarguments.

- The Rogerian model analyzes two sides of an argument and reaches a conclusion after weighing the strengths and weaknesses of each.

3 Good Argumentative Essay Examples + Analysis

Below are three examples of argumentative essays, written by yours truly in my school days, as well as analysis of what each did well and where it could be improved.

Argumentative Essay Example 1

Proponents of this idea state that it will save local cities and towns money because libraries are expensive to maintain. They also believe it will encourage more people to read because they won’t have to travel to a library to get a book; they can simply click on what they want to read and read it from wherever they are. They could also access more materials because libraries won’t have to buy physical copies of books; they can simply rent out as many digital copies as they need.

However, it would be a serious mistake to replace libraries with tablets. First, digital books and resources are associated with less learning and more problems than print resources. A study done on tablet vs book reading found that people read 20-30% slower on tablets, retain 20% less information, and understand 10% less of what they read compared to people who read the same information in print. Additionally, staring too long at a screen has been shown to cause numerous health problems, including blurred vision, dizziness, dry eyes, headaches, and eye strain, at much higher instances than reading print does. People who use tablets and mobile devices excessively also have a higher incidence of more serious health issues such as fibromyalgia, shoulder and back pain, carpal tunnel syndrome, and muscle strain. I know that whenever I read from my e-reader for too long, my eyes begin to feel tired and my neck hurts. We should not add to these problems by giving people, especially young people, more reasons to look at screens.

Second, it is incredibly narrow-minded to assume that the only service libraries offer is book lending. Libraries have a multitude of benefits, and many are only available if the library has a physical location. Some of these benefits include acting as a quiet study space, giving people a way to converse with their neighbors, holding classes on a variety of topics, providing jobs, answering patron questions, and keeping the community connected. One neighborhood found that, after a local library instituted community events such as play times for toddlers and parents, job fairs for teenagers, and meeting spaces for senior citizens, over a third of residents reported feeling more connected to their community. Similarly, a Pew survey conducted in 2015 found that nearly two-thirds of American adults feel that closing their local library would have a major impact on their community. People see libraries as a way to connect with others and get their questions answered, benefits tablets can’t offer nearly as well or as easily.

While replacing libraries with tablets may seem like a simple solution, it would encourage people to spend even more time looking at digital screens, despite the myriad issues surrounding them. It would also end access to many of the benefits of libraries that people have come to rely on. In many areas, libraries are such an important part of the community network that they could never be replaced by a simple object.

The author begins by giving an overview of the counter-argument, then the thesis appears as the first sentence in the third paragraph. The essay then spends the rest of the paper dismantling the counter argument and showing why readers should believe the other side.

What this essay does well:

- Although it’s a bit unusual to have the thesis appear fairly far into the essay, it works because, once the thesis is stated, the rest of the essay focuses on supporting it since the counter-argument has already been discussed earlier in the paper.

- This essay includes numerous facts and cites studies to support its case. By having specific data to rely on, the author’s argument is stronger and readers will be more inclined to agree with it.

- For every argument the other side makes, the author makes sure to refute it and follow up with why her opinion is the stronger one. In order to make a strong argument, it’s important to dismantle the other side, which this essay does this by making the author's view appear stronger.

- This is a shorter paper, and if it needed to be expanded to meet length requirements, it could include more examples and go more into depth with them, such as by explaining specific cases where people benefited from local libraries.

- Additionally, while the paper uses lots of data, the author also mentions their own experience with using tablets. This should be removed since argumentative essays focus on facts and data to support an argument, not the author’s own opinion or experiences. Replacing that with more data on health issues associated with screen time would strengthen the essay.

- Some of the points made aren't completely accurate , particularly the one about digital books being cheaper. It actually often costs a library more money to rent out numerous digital copies of a book compared to buying a single physical copy. Make sure in your own essay you thoroughly research each of the points and rebuttals you make, otherwise you'll look like you don't know the issue that well.

Argumentative Essay Example 2

There are multiple drugs available to treat malaria, and many of them work well and save lives, but malaria eradication programs that focus too much on them and not enough on prevention haven’t seen long-term success in Sub-Saharan Africa. A major program to combat malaria was WHO’s Global Malaria Eradication Programme. Started in 1955, it had a goal of eliminating malaria in Africa within the next ten years. Based upon previously successful programs in Brazil and the United States, the program focused mainly on vector control. This included widely distributing chloroquine and spraying large amounts of DDT. More than one billion dollars was spent trying to abolish malaria. However, the program suffered from many problems and in 1969, WHO was forced to admit that the program had not succeeded in eradicating malaria. The number of people in Sub-Saharan Africa who contracted malaria as well as the number of malaria deaths had actually increased over 10% during the time the program was active.

One of the major reasons for the failure of the project was that it set uniform strategies and policies. By failing to consider variations between governments, geography, and infrastructure, the program was not nearly as successful as it could have been. Sub-Saharan Africa has neither the money nor the infrastructure to support such an elaborate program, and it couldn’t be run the way it was meant to. Most African countries don't have the resources to send all their people to doctors and get shots, nor can they afford to clear wetlands or other malaria prone areas. The continent’s spending per person for eradicating malaria was just a quarter of what Brazil spent. Sub-Saharan Africa simply can’t rely on a plan that requires more money, infrastructure, and expertise than they have to spare.

Additionally, the widespread use of chloroquine has created drug resistant parasites which are now plaguing Sub-Saharan Africa. Because chloroquine was used widely but inconsistently, mosquitoes developed resistance, and chloroquine is now nearly completely ineffective in Sub-Saharan Africa, with over 95% of mosquitoes resistant to it. As a result, newer, more expensive drugs need to be used to prevent and treat malaria, which further drives up the cost of malaria treatment for a region that can ill afford it.

Instead of developing plans to treat malaria after the infection has incurred, programs should focus on preventing infection from occurring in the first place. Not only is this plan cheaper and more effective, reducing the number of people who contract malaria also reduces loss of work/school days which can further bring down the productivity of the region.

One of the cheapest and most effective ways of preventing malaria is to implement insecticide-treated bed nets (ITNs). These nets provide a protective barrier around the person or people using them. While untreated bed nets are still helpful, those treated with insecticides are much more useful because they stop mosquitoes from biting people through the nets, and they help reduce mosquito populations in a community, thus helping people who don’t even own bed nets. Bed nets are also very effective because most mosquito bites occur while the person is sleeping, so bed nets would be able to drastically reduce the number of transmissions during the night. In fact, transmission of malaria can be reduced by as much as 90% in areas where the use of ITNs is widespread. Because money is so scarce in Sub-Saharan Africa, the low cost is a great benefit and a major reason why the program is so successful. Bed nets cost roughly 2 USD to make, last several years, and can protect two adults. Studies have shown that, for every 100-1000 more nets are being used, one less child dies of malaria. With an estimated 300 million people in Africa not being protected by mosquito nets, there’s the potential to save three million lives by spending just a few dollars per person.

Reducing the number of people who contract malaria would also reduce poverty levels in Africa significantly, thus improving other aspects of society like education levels and the economy. Vector control is more effective than treatment strategies because it means fewer people are getting sick. When fewer people get sick, the working population is stronger as a whole because people are not put out of work from malaria, nor are they caring for sick relatives. Malaria-afflicted families can typically only harvest 40% of the crops that healthy families can harvest. Additionally, a family with members who have malaria spends roughly a quarter of its income treatment, not including the loss of work they also must deal with due to the illness. It’s estimated that malaria costs Africa 12 billion USD in lost income every year. A strong working population creates a stronger economy, which Sub-Saharan Africa is in desperate need of.

This essay begins with an introduction, which ends with the thesis (that malaria eradication plans in Sub-Saharan Africa should focus on prevention rather than treatment). The first part of the essay lays out why the counter argument (treatment rather than prevention) is not as effective, and the second part of the essay focuses on why prevention of malaria is the better path to take.

- The thesis appears early, is stated clearly, and is supported throughout the rest of the essay. This makes the argument clear for readers to understand and follow throughout the essay.

- There’s lots of solid research in this essay, including specific programs that were conducted and how successful they were, as well as specific data mentioned throughout. This evidence helps strengthen the author’s argument.

- The author makes a case for using expanding bed net use over waiting until malaria occurs and beginning treatment, but not much of a plan is given for how the bed nets would be distributed or how to ensure they’re being used properly. By going more into detail of what she believes should be done, the author would be making a stronger argument.

- The introduction of the essay does a good job of laying out the seriousness of the problem, but the conclusion is short and abrupt. Expanding it into its own paragraph would give the author a final way to convince readers of her side of the argument.

Argumentative Essay Example 3

There are many ways payments could work. They could be in the form of a free-market approach, where athletes are able to earn whatever the market is willing to pay them, it could be a set amount of money per athlete, or student athletes could earn income from endorsements, autographs, and control of their likeness, similar to the way top Olympians earn money.

Proponents of the idea believe that, because college athletes are the ones who are training, participating in games, and bringing in audiences, they should receive some sort of compensation for their work. If there were no college athletes, the NCAA wouldn’t exist, college coaches wouldn’t receive there (sometimes very high) salaries, and brands like Nike couldn’t profit from college sports. In fact, the NCAA brings in roughly $1 billion in revenue a year, but college athletes don’t receive any of that money in the form of a paycheck. Additionally, people who believe college athletes should be paid state that paying college athletes will actually encourage them to remain in college longer and not turn pro as quickly, either by giving them a way to begin earning money in college or requiring them to sign a contract stating they’ll stay at the university for a certain number of years while making an agreed-upon salary.

Supporters of this idea point to Zion Williamson, the Duke basketball superstar, who, during his freshman year, sustained a serious knee injury. Many argued that, even if he enjoyed playing for Duke, it wasn’t worth risking another injury and ending his professional career before it even began for a program that wasn’t paying him. Williamson seems to have agreed with them and declared his eligibility for the NCAA draft later that year. If he was being paid, he may have stayed at Duke longer. In fact, roughly a third of student athletes surveyed stated that receiving a salary while in college would make them “strongly consider” remaining collegiate athletes longer before turning pro.

Paying athletes could also stop the recruitment scandals that have plagued the NCAA. In 2018, the NCAA stripped the University of Louisville's men's basketball team of its 2013 national championship title because it was discovered coaches were using sex workers to entice recruits to join the team. There have been dozens of other recruitment scandals where college athletes and recruits have been bribed with anything from having their grades changed, to getting free cars, to being straight out bribed. By paying college athletes and putting their salaries out in the open, the NCAA could end the illegal and underhanded ways some schools and coaches try to entice athletes to join.

People who argue against the idea of paying college athletes believe the practice could be disastrous for college sports. By paying athletes, they argue, they’d turn college sports into a bidding war, where only the richest schools could afford top athletes, and the majority of schools would be shut out from developing a talented team (though some argue this already happens because the best players often go to the most established college sports programs, who typically pay their coaches millions of dollars per year). It could also ruin the tight camaraderie of many college teams if players become jealous that certain teammates are making more money than they are.

They also argue that paying college athletes actually means only a small fraction would make significant money. Out of the 350 Division I athletic departments, fewer than a dozen earn any money. Nearly all the money the NCAA makes comes from men’s football and basketball, so paying college athletes would make a small group of men--who likely will be signed to pro teams and begin making millions immediately out of college--rich at the expense of other players.

Those against paying college athletes also believe that the athletes are receiving enough benefits already. The top athletes already receive scholarships that are worth tens of thousands per year, they receive free food/housing/textbooks, have access to top medical care if they are injured, receive top coaching, get travel perks and free gear, and can use their time in college as a way to capture the attention of professional recruiters. No other college students receive anywhere near as much from their schools.

People on this side also point out that, while the NCAA brings in a massive amount of money each year, it is still a non-profit organization. How? Because over 95% of those profits are redistributed to its members’ institutions in the form of scholarships, grants, conferences, support for Division II and Division III teams, and educational programs. Taking away a significant part of that revenue would hurt smaller programs that rely on that money to keep running.

While both sides have good points, it’s clear that the negatives of paying college athletes far outweigh the positives. College athletes spend a significant amount of time and energy playing for their school, but they are compensated for it by the scholarships and perks they receive. Adding a salary to that would result in a college athletic system where only a small handful of athletes (those likely to become millionaires in the professional leagues) are paid by a handful of schools who enter bidding wars to recruit them, while the majority of student athletics and college athletic programs suffer or even shut down for lack of money. Continuing to offer the current level of benefits to student athletes makes it possible for as many people to benefit from and enjoy college sports as possible.

This argumentative essay follows the Rogerian model. It discusses each side, first laying out multiple reasons people believe student athletes should be paid, then discussing reasons why the athletes shouldn’t be paid. It ends by stating that college athletes shouldn’t be paid by arguing that paying them would destroy college athletics programs and cause them to have many of the issues professional sports leagues have.

- Both sides of the argument are well developed, with multiple reasons why people agree with each side. It allows readers to get a full view of the argument and its nuances.

- Certain statements on both sides are directly rebuffed in order to show where the strengths and weaknesses of each side lie and give a more complete and sophisticated look at the argument.

- Using the Rogerian model can be tricky because oftentimes you don’t explicitly state your argument until the end of the paper. Here, the thesis doesn’t appear until the first sentence of the final paragraph. That doesn’t give readers a lot of time to be convinced that your argument is the right one, compared to a paper where the thesis is stated in the beginning and then supported throughout the paper. This paper could be strengthened if the final paragraph was expanded to more fully explain why the author supports the view, or if the paper had made it clearer that paying athletes was the weaker argument throughout.

3 Tips for Writing a Good Argumentative Essay

Now that you’ve seen examples of what good argumentative essay samples look like, follow these three tips when crafting your own essay.

#1: Make Your Thesis Crystal Clear

The thesis is the key to your argumentative essay; if it isn’t clear or readers can’t find it easily, your entire essay will be weak as a result. Always make sure that your thesis statement is easy to find. The typical spot for it is the final sentence of the introduction paragraph, but if it doesn’t fit in that spot for your essay, try to at least put it as the first or last sentence of a different paragraph so it stands out more.

Also make sure that your thesis makes clear what side of the argument you’re on. After you’ve written it, it’s a great idea to show your thesis to a couple different people--classmates are great for this. Just by reading your thesis they should be able to understand what point you’ll be trying to make with the rest of your essay.

#2: Show Why the Other Side Is Weak

When writing your essay, you may be tempted to ignore the other side of the argument and just focus on your side, but don’t do this. The best argumentative essays really tear apart the other side to show why readers shouldn’t believe it. Before you begin writing your essay, research what the other side believes, and what their strongest points are. Then, in your essay, be sure to mention each of these and use evidence to explain why they’re incorrect/weak arguments. That’ll make your essay much more effective than if you only focused on your side of the argument.

#3: Use Evidence to Support Your Side

Remember, an essay can’t be an argumentative essay if it doesn’t support its argument with evidence. For every point you make, make sure you have facts to back it up. Some examples are previous studies done on the topic, surveys of large groups of people, data points, etc. There should be lots of numbers in your argumentative essay that support your side of the argument. This will make your essay much stronger compared to only relying on your own opinions to support your argument.

Summary: Argumentative Essay Sample

Argumentative essays are persuasive essays that use facts and evidence to support their side of the argument. Most argumentative essays follow either the Toulmin model or the Rogerian model. By reading good argumentative essay examples, you can learn how to develop your essay and provide enough support to make readers agree with your opinion. When writing your essay, remember to always make your thesis clear, show where the other side is weak, and back up your opinion with data and evidence.

What's Next?

Do you need to write an argumentative essay as well? Check out our guide on the best argumentative essay topics for ideas!

You'll probably also need to write research papers for school. We've got you covered with 113 potential topics for research papers.

Your college admissions essay may end up being one of the most important essays you write. Follow our step-by-step guide on writing a personal statement to have an essay that'll impress colleges.

Christine graduated from Michigan State University with degrees in Environmental Biology and Geography and received her Master's from Duke University. In high school she scored in the 99th percentile on the SAT and was named a National Merit Finalist. She has taught English and biology in several countries.

Student and Parent Forum

Our new student and parent forum, at ExpertHub.PrepScholar.com , allow you to interact with your peers and the PrepScholar staff. See how other students and parents are navigating high school, college, and the college admissions process. Ask questions; get answers.

Ask a Question Below

Have any questions about this article or other topics? Ask below and we'll reply!

Improve With Our Famous Guides

- For All Students

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 160+ SAT Points

How to Get a Perfect 1600, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 800 on Each SAT Section:

Score 800 on SAT Math

Score 800 on SAT Reading

Score 800 on SAT Writing

Series: How to Get to 600 on Each SAT Section:

Score 600 on SAT Math

Score 600 on SAT Reading

Score 600 on SAT Writing

Free Complete Official SAT Practice Tests

What SAT Target Score Should You Be Aiming For?

15 Strategies to Improve Your SAT Essay

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 4+ ACT Points

How to Get a Perfect 36 ACT, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 36 on Each ACT Section:

36 on ACT English

36 on ACT Math

36 on ACT Reading

36 on ACT Science

Series: How to Get to 24 on Each ACT Section:

24 on ACT English

24 on ACT Math

24 on ACT Reading

24 on ACT Science

What ACT target score should you be aiming for?

ACT Vocabulary You Must Know

ACT Writing: 15 Tips to Raise Your Essay Score

How to Get Into Harvard and the Ivy League

How to Get a Perfect 4.0 GPA

How to Write an Amazing College Essay

What Exactly Are Colleges Looking For?

Is the ACT easier than the SAT? A Comprehensive Guide

Should you retake your SAT or ACT?

When should you take the SAT or ACT?

Stay Informed

Get the latest articles and test prep tips!

Looking for Graduate School Test Prep?

Check out our top-rated graduate blogs here:

GRE Online Prep Blog

GMAT Online Prep Blog

TOEFL Online Prep Blog

Holly R. "I am absolutely overjoyed and cannot thank you enough for helping me!”

Places on our 2024 summer school are filling fast. Don’t miss out. Enrol now to avoid disappointment

- 40 Useful Words and Phrases for Top-Notch Essays

To be truly brilliant, an essay needs to utilise the right language. You could make a great point, but if it’s not intelligently articulated, you almost needn’t have bothered.

Developing the language skills to build an argument and to write persuasively is crucial if you’re to write outstanding essays every time. In this article, we’re going to equip you with the words and phrases you need to write a top-notch essay, along with examples of how to utilise them.

It’s by no means an exhaustive list, and there will often be other ways of using the words and phrases we describe that we won’t have room to include, but there should be more than enough below to help you make an instant improvement to your essay-writing skills.

If you’re interested in developing your language and persuasive skills, Oxford Royale offers summer courses at its Oxford Summer School , Cambridge Summer School , London Summer School , San Francisco Summer School and Yale Summer School . You can study courses to learn english , prepare for careers in law , medicine , business , engineering and leadership.

General explaining

Let’s start by looking at language for general explanations of complex points.

1. In order to

Usage: “In order to” can be used to introduce an explanation for the purpose of an argument. Example: “In order to understand X, we need first to understand Y.”

2. In other words

Usage: Use “in other words” when you want to express something in a different way (more simply), to make it easier to understand, or to emphasise or expand on a point. Example: “Frogs are amphibians. In other words, they live on the land and in the water.”

3. To put it another way

Usage: This phrase is another way of saying “in other words”, and can be used in particularly complex points, when you feel that an alternative way of wording a problem may help the reader achieve a better understanding of its significance. Example: “Plants rely on photosynthesis. To put it another way, they will die without the sun.”

4. That is to say

Usage: “That is” and “that is to say” can be used to add further detail to your explanation, or to be more precise. Example: “Whales are mammals. That is to say, they must breathe air.”

5. To that end

Usage: Use “to that end” or “to this end” in a similar way to “in order to” or “so”. Example: “Zoologists have long sought to understand how animals communicate with each other. To that end, a new study has been launched that looks at elephant sounds and their possible meanings.”

Adding additional information to support a point

Students often make the mistake of using synonyms of “and” each time they want to add further information in support of a point they’re making, or to build an argument . Here are some cleverer ways of doing this.

6. Moreover

Usage: Employ “moreover” at the start of a sentence to add extra information in support of a point you’re making. Example: “Moreover, the results of a recent piece of research provide compelling evidence in support of…”

7. Furthermore

Usage:This is also generally used at the start of a sentence, to add extra information. Example: “Furthermore, there is evidence to suggest that…”

8. What’s more

Usage: This is used in the same way as “moreover” and “furthermore”. Example: “What’s more, this isn’t the only evidence that supports this hypothesis.”

9. Likewise

Usage: Use “likewise” when you want to talk about something that agrees with what you’ve just mentioned. Example: “Scholar A believes X. Likewise, Scholar B argues compellingly in favour of this point of view.”

10. Similarly

Usage: Use “similarly” in the same way as “likewise”. Example: “Audiences at the time reacted with shock to Beethoven’s new work, because it was very different to what they were used to. Similarly, we have a tendency to react with surprise to the unfamiliar.”

11. Another key thing to remember

Usage: Use the phrase “another key point to remember” or “another key fact to remember” to introduce additional facts without using the word “also”. Example: “As a Romantic, Blake was a proponent of a closer relationship between humans and nature. Another key point to remember is that Blake was writing during the Industrial Revolution, which had a major impact on the world around him.”

12. As well as

Usage: Use “as well as” instead of “also” or “and”. Example: “Scholar A argued that this was due to X, as well as Y.”

13. Not only… but also

Usage: This wording is used to add an extra piece of information, often something that’s in some way more surprising or unexpected than the first piece of information. Example: “Not only did Edmund Hillary have the honour of being the first to reach the summit of Everest, but he was also appointed Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire.”

14. Coupled with

Usage: Used when considering two or more arguments at a time. Example: “Coupled with the literary evidence, the statistics paint a compelling view of…”

15. Firstly, secondly, thirdly…

Usage: This can be used to structure an argument, presenting facts clearly one after the other. Example: “There are many points in support of this view. Firstly, X. Secondly, Y. And thirdly, Z.

16. Not to mention/to say nothing of

Usage: “Not to mention” and “to say nothing of” can be used to add extra information with a bit of emphasis. Example: “The war caused unprecedented suffering to millions of people, not to mention its impact on the country’s economy.”

Words and phrases for demonstrating contrast

When you’re developing an argument, you will often need to present contrasting or opposing opinions or evidence – “it could show this, but it could also show this”, or “X says this, but Y disagrees”. This section covers words you can use instead of the “but” in these examples, to make your writing sound more intelligent and interesting.

17. However

Usage: Use “however” to introduce a point that disagrees with what you’ve just said. Example: “Scholar A thinks this. However, Scholar B reached a different conclusion.”

18. On the other hand

Usage: Usage of this phrase includes introducing a contrasting interpretation of the same piece of evidence, a different piece of evidence that suggests something else, or an opposing opinion. Example: “The historical evidence appears to suggest a clear-cut situation. On the other hand, the archaeological evidence presents a somewhat less straightforward picture of what happened that day.”

19. Having said that

Usage: Used in a similar manner to “on the other hand” or “but”. Example: “The historians are unanimous in telling us X, an agreement that suggests that this version of events must be an accurate account. Having said that, the archaeology tells a different story.”

20. By contrast/in comparison

Usage: Use “by contrast” or “in comparison” when you’re comparing and contrasting pieces of evidence. Example: “Scholar A’s opinion, then, is based on insufficient evidence. By contrast, Scholar B’s opinion seems more plausible.”

21. Then again

Usage: Use this to cast doubt on an assertion. Example: “Writer A asserts that this was the reason for what happened. Then again, it’s possible that he was being paid to say this.”

22. That said

Usage: This is used in the same way as “then again”. Example: “The evidence ostensibly appears to point to this conclusion. That said, much of the evidence is unreliable at best.”

Usage: Use this when you want to introduce a contrasting idea. Example: “Much of scholarship has focused on this evidence. Yet not everyone agrees that this is the most important aspect of the situation.”

Adding a proviso or acknowledging reservations

Sometimes, you may need to acknowledge a shortfalling in a piece of evidence, or add a proviso. Here are some ways of doing so.

24. Despite this

Usage: Use “despite this” or “in spite of this” when you want to outline a point that stands regardless of a shortfalling in the evidence. Example: “The sample size was small, but the results were important despite this.”

25. With this in mind

Usage: Use this when you want your reader to consider a point in the knowledge of something else. Example: “We’ve seen that the methods used in the 19th century study did not always live up to the rigorous standards expected in scientific research today, which makes it difficult to draw definite conclusions. With this in mind, let’s look at a more recent study to see how the results compare.”

26. Provided that

Usage: This means “on condition that”. You can also say “providing that” or just “providing” to mean the same thing. Example: “We may use this as evidence to support our argument, provided that we bear in mind the limitations of the methods used to obtain it.”

27. In view of/in light of

Usage: These phrases are used when something has shed light on something else. Example: “In light of the evidence from the 2013 study, we have a better understanding of…”

28. Nonetheless

Usage: This is similar to “despite this”. Example: “The study had its limitations, but it was nonetheless groundbreaking for its day.”

29. Nevertheless

Usage: This is the same as “nonetheless”. Example: “The study was flawed, but it was important nevertheless.”

30. Notwithstanding

Usage: This is another way of saying “nonetheless”. Example: “Notwithstanding the limitations of the methodology used, it was an important study in the development of how we view the workings of the human mind.”

Giving examples

Good essays always back up points with examples, but it’s going to get boring if you use the expression “for example” every time. Here are a couple of other ways of saying the same thing.

31. For instance

Example: “Some birds migrate to avoid harsher winter climates. Swallows, for instance, leave the UK in early winter and fly south…”

32. To give an illustration

Example: “To give an illustration of what I mean, let’s look at the case of…”

Signifying importance

When you want to demonstrate that a point is particularly important, there are several ways of highlighting it as such.

33. Significantly

Usage: Used to introduce a point that is loaded with meaning that might not be immediately apparent. Example: “Significantly, Tacitus omits to tell us the kind of gossip prevalent in Suetonius’ accounts of the same period.”

34. Notably

Usage: This can be used to mean “significantly” (as above), and it can also be used interchangeably with “in particular” (the example below demonstrates the first of these ways of using it). Example: “Actual figures are notably absent from Scholar A’s analysis.”

35. Importantly

Usage: Use “importantly” interchangeably with “significantly”. Example: “Importantly, Scholar A was being employed by X when he wrote this work, and was presumably therefore under pressure to portray the situation more favourably than he perhaps might otherwise have done.”

Summarising

You’ve almost made it to the end of the essay, but your work isn’t over yet. You need to end by wrapping up everything you’ve talked about, showing that you’ve considered the arguments on both sides and reached the most likely conclusion. Here are some words and phrases to help you.

36. In conclusion

Usage: Typically used to introduce the concluding paragraph or sentence of an essay, summarising what you’ve discussed in a broad overview. Example: “In conclusion, the evidence points almost exclusively to Argument A.”

37. Above all

Usage: Used to signify what you believe to be the most significant point, and the main takeaway from the essay. Example: “Above all, it seems pertinent to remember that…”

38. Persuasive

Usage: This is a useful word to use when summarising which argument you find most convincing. Example: “Scholar A’s point – that Constanze Mozart was motivated by financial gain – seems to me to be the most persuasive argument for her actions following Mozart’s death.”

39. Compelling

Usage: Use in the same way as “persuasive” above. Example: “The most compelling argument is presented by Scholar A.”

40. All things considered

Usage: This means “taking everything into account”. Example: “All things considered, it seems reasonable to assume that…”

How many of these words and phrases will you get into your next essay? And are any of your favourite essay terms missing from our list? Let us know in the comments below, or get in touch here to find out more about courses that can help you with your essays.

At Oxford Royale Academy, we offer a number of summer school courses for young people who are keen to improve their essay writing skills. Click here to apply for one of our courses today, including law , business , medicine and engineering .

Comments are closed.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- 25 April 2024

- Correction 25 April 2024

‘Shut up and calculate’: how Einstein lost the battle to explain quantum reality

- Jim Baggott 0

Jim Baggott is a science writer based in Cape Town, South Africa. He is co-author with John Heilbron of Quantum Drama .

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

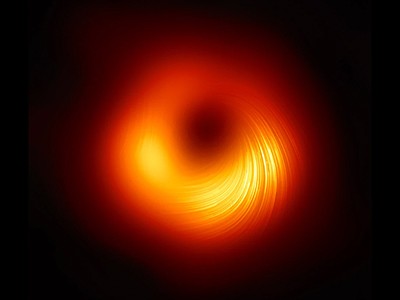

For entangled particles, a change in one instantly affects the other, no matter how far apart they are. Credit: Volker Steger/SPL

You have full access to this article via your institution.

Quantum mechanics is an extraordinarily successful scientific theory, on which much of our technology-obsessed lifestyles depend. It is also bewildering. Although the theory works, it leaves physicists chasing probabilities instead of certainties and breaks the link between cause and effect. It gives us particles that are waves and waves that are particles , cats that seem to be both alive and dead, and lots of spooky quantum weirdness around hard-to-explain phenomena, such as quantum entanglement.

Myths are also rife. For instance, in the early twentieth century, when the theory’s founders were arguing among themselves about what it all meant, the views of Danish physicist Niels Bohr came to dominate. Albert Einstein famously disagreed with him and, in the 1920s and 1930s, the two locked horns in debate . A persistent myth was created that suggests Bohr won the argument by browbeating the stubborn and increasingly isolated Einstein into submission. Acting like some fanatical priesthood, physicists of Bohr’s ‘church’ sought to shut down further debate. They established the ‘Copenhagen interpretation’, named after the location of Bohr’s institute, as a dogmatic orthodoxy.

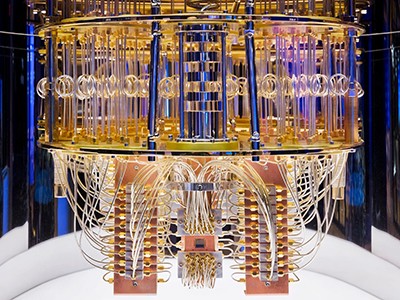

My latest book Quantum Drama , co-written with science historian John Heilbron, explores the origins of this myth and its role in motivating the singular personalities that would go on to challenge it. Their persistence in the face of widespread indifference paid off, because they helped to lay the foundations for a quantum-computing industry expected to be worth tens of billions by 2040.

John died on 5 November 2023 , so sadly did not see his last work through to publication. This essay is dedicated to his memory.

Foundational myth

A scientific myth is not produced by accident or error. It requires effort. “To qualify as a myth, a false claim should be persistent and widespread,” Heilbron said in a 2014 conference talk. “It should have a plausible and assignable reason for its endurance, and immediate cultural relevance,” he noted. “Although erroneous or fabulous, such myths are not entirely wrong, and their exaggerations bring out aspects of a situation, relationship or project that might otherwise be ignored.”

Does quantum theory imply the entire Universe is preordained?

To see how these observations apply to the historical development of quantum mechanics, let’s look more closely at the Bohr–Einstein debate. The only way to make sense of the theory, Bohr argued in 1927, was to accept his principle of complementarity. Physicists have no choice but to describe quantum experiments and their results using wholly incompatible, yet complementary, concepts borrowed from classical physics.

In one kind of experiment, an electron, for example, behaves like a classical wave. In another, it behaves like a classical particle. Physicists can observe only one type of behaviour at a time, because there is no experiment that can be devised that could show both behaviours at once.

Bohr insisted that there is no contradiction in complementarity, because the use of these classical concepts is purely symbolic. This was not about whether electrons are really waves or particles. It was about accepting that physicists can never know what an electron really is and that they must reach for symbolic descriptions of waves and particles as appropriate. With these restrictions, Bohr regarded the theory to be complete — no further elaboration was necessary.

Such a pronouncement prompts an important question. What is the purpose of physics? Is its main goal to gain ever-more-detailed descriptions and control of phenomena, regardless of whether physicists can understand these descriptions? Or, rather, is it a continuing search for deeper and deeper insights into the nature of physical reality?

Einstein preferred the second answer, and refused to accept that complementarity could be the last word on the subject. In his debate with Bohr, he devised a series of elaborate thought experiments, in which he sought to demonstrate the theory’s inconsistencies and ambiguities, and its incompleteness. These were intended to highlight matters of principle; they were not meant to be taken literally.

Entangled probabilities

In 1935, Einstein’s criticisms found their focus in a paper 1 published with his colleagues Boris Podolsky and Nathan Rosen at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey. In their thought experiment (known as EPR, the authors’ initials), a pair of particles (A and B) interact and move apart. Suppose each particle can possess, with equal probability, one of two quantum properties, which for simplicity I will call ‘up’ and ‘down’, measured in relation to some instrument setting. Assuming their properties are correlated by a physical law, if A is measured to be ‘up’, B must be ‘down’, and vice versa. The Austrian physicist Erwin Schrödinger invented the term entangled to describe this kind of situation.

How Einstein built on the past to make his breakthroughs

If the entangled particles are allowed to move so far apart that they can no longer affect one another, physicists might say that they are no longer in ‘causal contact’. Quantum mechanics predicts that scientists should still be able to measure A and thereby — with certainty — infer the correlated property of B.

But the theory gives us only probabilities. We have no way of knowing in advance what result we will get for A. If A is found to be ‘down’, how does the distant, causally disconnected B ‘know’ how to correlate with its entangled partner and give the result ‘up’? The particles cannot break the correlation, because this would break the physical law that created it.

Physicists could simply assume that, when far enough apart, the particles are separate and distinct, or ‘locally real’, each possessing properties that were fixed at the moment of their interaction. Suppose A sets off towards a measuring instrument carrying the property ‘up’. A devious experimenter is perfectly at liberty to change the instrument setting so that when A arrives, it is now measured to be ‘down’. How, then, is the correlation established? Do the particles somehow remain in contact, sending messages to each other or exerting influences on each other over vast distances at speeds faster than light, in conflict with Einstein’s special theory of relativity?

The alternative possibility, equally discomforting to contemplate, is that the entangled particles do not actually exist independently of each other. They are ‘non-local’, implying that their properties are not fixed until a measurement is made on one of them.

Both these alternatives were unacceptable to Einstein, leading him to conclude that quantum mechanics cannot be complete.

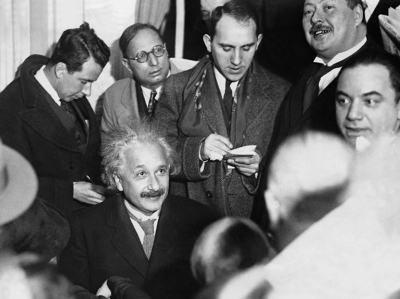

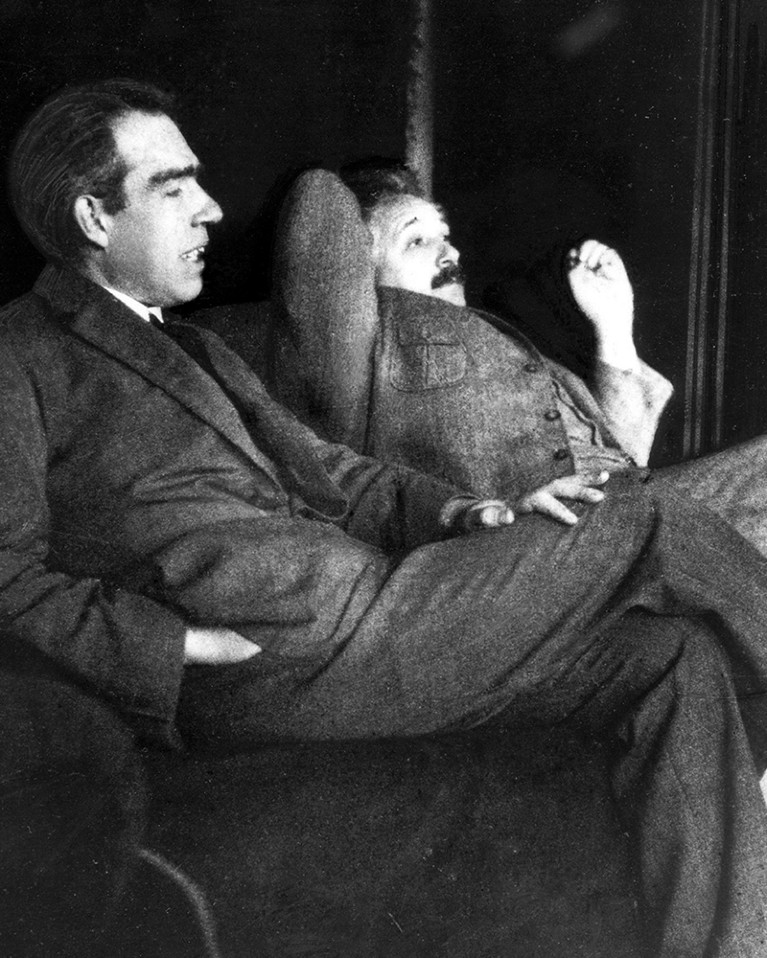

Niels Bohr (left) and Albert Einstein. Credit: Universal History Archive/Universal Images Group via Getty

The EPR thought experiment delivered a shock to Bohr’s camp, but it was quickly (if unconvincingly) rebuffed by Bohr. Einstein’s challenge was not enough; he was content to criticize the theory but there was no consensus on an alternative to Bohr’s complementarity. Bohr was judged by the wider scientific community to have won the debate and, by the early 1950s, Einstein’s star was waning.