- Search Search Please fill out this field.

What Is Ratio Analysis?

- What Does It Tell You?

- Application

The Bottom Line

- Corporate Finance

- Financial Ratios

Financial Ratio Analysis: Definition, Types, Examples, and How to Use

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/andrew_bloomenthal_bio_photo-5bfc262ec9e77c005199a327.png)

- Valuing a Company: Business Valuation Defined With 6 Methods

- Valuation Analysis

- Financial Statements

- Balance Sheet

- Cash Flow Statement

- 6 Basic Financial Ratios

- 5 Must-Have Metrics for Value Investors

- Earnings Per Share (EPS)

- Price-to-Earnings Ratio (P/E Ratio)

- Price-To-Book Ratio (P/B Ratio)

- Price/Earnings-to-Growth (PEG Ratio)

- Fundamental Analysis

- Absolute Value

- Relative Valuation

- Intrinsic Value of a Stock

- Intrinsic Value vs. Current Market Value

- Equity Valuation: The Comparables Approach

- 4 Basic Elements of Stock Value

- How to Become Your Own Stock Analyst

- Due Diligence in 10 Easy Steps

- Determining the Value of a Preferred Stock

- Qualitative Analysis

- Stock Valuation Methods

- Bottom-Up Investing

- Ratio Analysis CURRENT ARTICLE

- What Book Value Means to Investors

- Liquidation Value

- Market Capitalization

- Discounted Cash Flow (DCF)

- Enterprise Value (EV)

- How to Use Enterprise Value to Compare Companies

- How to Analyze Corporate Profit Margins

- Return on Equity (ROE)

- Decoding DuPont Analysis

- How to Value Private Companies

- Valuing Startup Ventures

Ratio analysis is a quantitative method of gaining insight into a company's liquidity, operational efficiency, and profitability by studying its financial statements such as the balance sheet and income statement. Ratio analysis is a cornerstone of fundamental equity analysis .

Key Takeaways

- Ratio analysis compares line-item data from a company's financial statements to reveal insights regarding profitability, liquidity, operational efficiency, and solvency.

- Ratio analysis can mark how a company is performing over time, while comparing a company to another within the same industry or sector.

- Ratio analysis may also be required by external parties that set benchmarks often tied to risk.

- While ratios offer useful insight into a company, they should be paired with other metrics, to obtain a broader picture of a company's financial health.

- Examples of ratio analysis include current ratio, gross profit margin ratio, inventory turnover ratio.

Investopedia / Theresa Chiechi

What Does Ratio Analysis Tell You?

Investors and analysts employ ratio analysis to evaluate the financial health of companies by scrutinizing past and current financial statements. Comparative data can demonstrate how a company is performing over time and can be used to estimate likely future performance. This data can also compare a company's financial standing with industry averages while measuring how a company stacks up against others within the same sector.

Investors can use ratio analysis easily, and every figure needed to calculate the ratios is found on a company's financial statements.

Ratios are comparison points for companies. They evaluate stocks within an industry. Likewise, they measure a company today against its historical numbers. In most cases, it is also important to understand the variables driving ratios as management has the flexibility to, at times, alter its strategy to make it's stock and company ratios more attractive. Generally, ratios are typically not used in isolation but rather in combination with other ratios. Having a good idea of the ratios in each of the four previously mentioned categories will give you a comprehensive view of the company from different angles and help you spot potential red flags.

A ratio is the relation between two amounts showing the number of times one value contains or is contained within the other.

Types of Ratio Analysis

The various kinds of financial ratios available may be broadly grouped into the following six silos, based on the sets of data they provide:

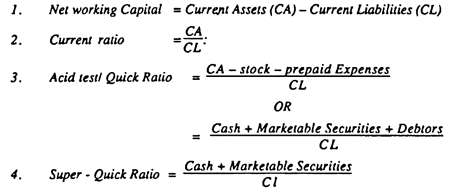

1. Liquidity Ratios

Liquidity ratios measure a company's ability to pay off its short-term debts as they become due, using the company's current or quick assets. Liquidity ratios include the current ratio, quick ratio, and working capital ratio.

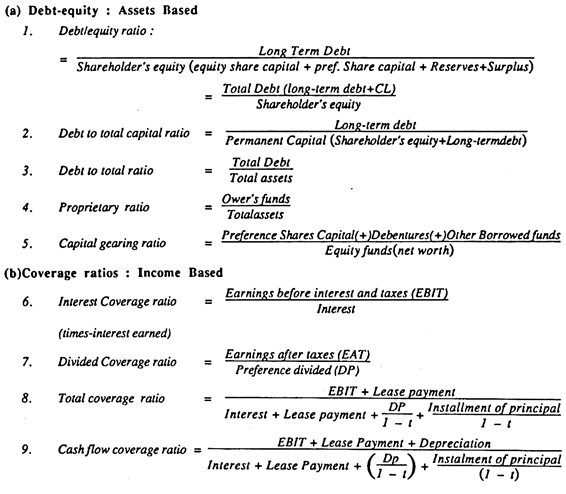

2. Solvency Ratios

Also called financial leverage ratios, solvency ratios compare a company's debt levels with its assets, equity, and earnings, to evaluate the likelihood of a company staying afloat over the long haul, by paying off its long-term debt as well as the interest on its debt. Examples of solvency ratios include: debt-equity ratios, debt-assets ratios, and interest coverage ratios.

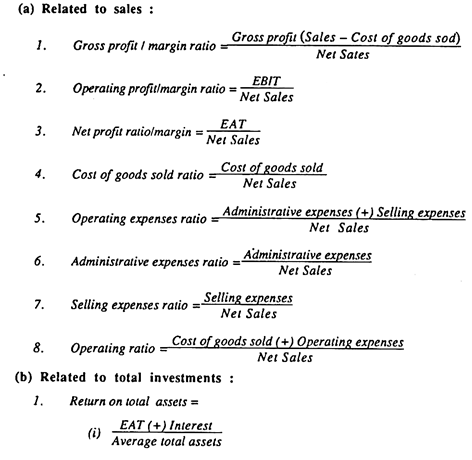

3. Profitability Ratios

These ratios convey how well a company can generate profits from its operations. Profit margin, return on assets, return on equity, return on capital employed, and gross margin ratios are all examples of profitability ratios .

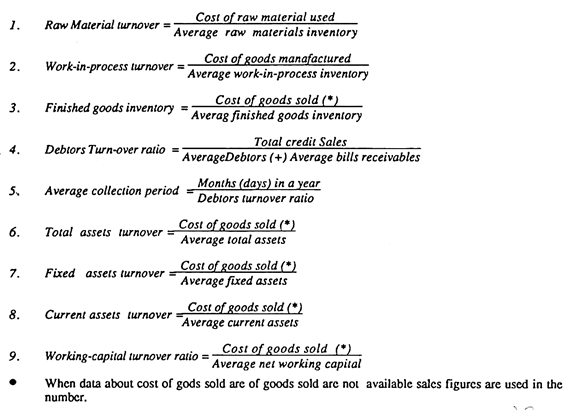

4. Efficiency Ratios

Also called activity ratios, efficiency ratios evaluate how efficiently a company uses its assets and liabilities to generate sales and maximize profits. Key efficiency ratios include: turnover ratio, inventory turnover, and days' sales in inventory.

5. Coverage Ratios

Coverage ratios measure a company's ability to make the interest payments and other obligations associated with its debts. Examples include the times interest earned ratio and the debt-service coverage ratio .

6. Market Prospect Ratios

These are the most commonly used ratios in fundamental analysis. They include dividend yield , P/E ratio , earnings per share (EPS), and dividend payout ratio . Investors use these metrics to predict earnings and future performance.

For example, if the average P/E ratio of all companies in the S&P 500 index is 20, and the majority of companies have P/Es between 15 and 25, a stock with a P/E ratio of seven would be considered undervalued. In contrast, one with a P/E ratio of 50 would be considered overvalued. The former may trend upwards in the future, while the latter may trend downwards until each aligns with its intrinsic value.

Most ratio analysis is only used for internal decision making. Though some benchmarks are set externally (discussed below), ratio analysis is often not a required aspect of budgeting or planning.

Application of Ratio Analysis

The fundamental basis of ratio analysis is to compare multiple figures and derive a calculated value. By itself, that value may hold little to no value. Instead, ratio analysis must often be applied to a comparable to determine whether or a company's financial health is strong, weak, improving, or deteriorating.

Ratio Analysis Over Time

A company can perform ratio analysis over time to get a better understanding of the trajectory of its company. Instead of being focused on where it is today, the company is more interested n how the company has performed over time, what changes have worked, and what risks still exist looking to the future. Performing ratio analysis is a central part in forming long-term decisions and strategic planning .

To perform ratio analysis over time, a company selects a single financial ratio, then calculates that ratio on a fixed cadence (i.e. calculating its quick ratio every month). Be mindful of seasonality and how temporarily fluctuations in account balances may impact month-over-month ratio calculations. Then, a company analyzes how the ratio has changed over time (whether it is improving, the rate at which it is changing, and whether the company wanted the ratio to change over time).

Ratio Analysis Across Companies

Imagine a company with a 10% gross profit margin. A company may be thrilled with this financial ratio until it learns that every competitor is achieving a gross profit margin of 25%. Ratio analysis is incredibly useful for a company to better stand how its performance compares to similar companies.

To correctly implement ratio analysis to compare different companies, consider only analyzing similar companies within the same industry . In addition, be mindful how different capital structures and company sizes may impact a company's ability to be efficient. In addition, consider how companies with varying product lines (i.e. some technology companies may offer products as well as services, two different product lines with varying impacts to ratio analysis).

Different industries simply have different ratio expectations. A debt-equity ratio that might be normal for a utility company that can obtain low-cost debt might be deemed unsustainably high for a technology company that relies more heavily on private investor funding.

Ratio Analysis Against Benchmarks

Companies may set internal targets for their financial ratios. These calculations may hold current levels steady or strive for operational growth. For example, a company's existing current ratio may be 1.1; if the company wants to become more liquid, it may set the internal target of having a current ratio of 1.2 by the end of the fiscal year.

Benchmarks are also frequently implemented by external parties such lenders. Lending institutions often set requirements for financial health as part of covenants in loan documents. Covenants form part of the loan's terms and conditions and companies must maintain certain metrics or the loan may be recalled.

If these benchmarks are not met, an entire loan may be callable or a company may be faced with an adjusted higher rate of interest to compensation for this risk. An example of a benchmark set by a lender is often the debt service coverage ratio which measures a company's cash flow against it's debt balances.

Examples of Ratio Analysis in Use

Ratio analysis can predict a company's future performance — for better or worse. Successful companies generally boast solid ratios in all areas, where any sudden hint of weakness in one area may spark a significant stock sell-off. Let's look at a few simple examples

Net profit margin , often referred to simply as profit margin or the bottom line, is a ratio that investors use to compare the profitability of companies within the same sector. It's calculated by dividing a company's net income by its revenues. Instead of dissecting financial statements to compare how profitable companies are, an investor can use this ratio instead. For example, suppose company ABC and company DEF are in the same sector with profit margins of 50% and 10%, respectively. An investor can easily compare the two companies and conclude that ABC converted 50% of its revenues into profits, while DEF only converted 10%.

Using the companies from the above example, suppose ABC has a P/E ratio of 100, while DEF has a P/E ratio of 10. An average investor concludes that investors are willing to pay $100 per $1 of earnings ABC generates and only $10 per $1 of earnings DEF generates.

What Are the Types of Ratio Analysis?

Financial ratio analysis is often broken into six different types: profitability, solvency, liquidity, turnover, coverage, and market prospects ratios. Other non-financial metrics may be scattered across various departments and industries. For example, a marketing department may use a conversion click ratio to analyze customer capture.

What Are the Uses of Ratio Analysis?

Ratio analysis serves three main uses. First, ratio analysis can be performed to track changes to a company over time to better understand the trajectory of operations. Second, ratio analysis can be performed to compare results with other similar companies to see how the company is doing compared to competitors. Third, ratio analysis can be performed to strive for specific internally-set or externally-set benchmarks.

Why Is Ratio Analysis Important?

Ratio analysis is important because it may portray a more accurate representation of the state of operations for a company. Consider a company that made $1 billion of revenue last quarter. Though this seems ideal, the company might have had a negative gross profit margin, a decrease in liquidity ratio metrics, and lower earnings compared to equity than in prior periods. Static numbers on their own may not fully explain how a company is performing.

What Is an Example of Ratio Analysis?

Consider the inventory turnover ratio that measures how quickly a company converts inventory to a sale. A company can track its inventory turnover over a full calendar year to see how quickly it converted goods to cash each month. Then, a company can explore the reasons certain months lagged or why certain months exceeded expectations.

There is often an overwhelming amount of data and information useful for a company to make decisions. To make better use of their information, a company may compare several numbers together. This process called ratio analysis allows a company to gain better insights to how it is performing over time, against competition, and against internal goals. Ratio analysis is usually rooted heavily with financial metrics, though ratio analysis can be performed with non-financial data.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/terms_l_liquidityratios_FINAL-d2c8aea76ba845b4a050eacd22566cae.jpg)

- Terms of Service

- Editorial Policy

- Privacy Policy

- Your Privacy Choices

Ratio and Financial Statement Analysis

Executive summary, introduction, liquidity ratios, profitability, investors’ ratios, benefits and limitations, new practices, conclusion and recommendation.

Financial ratios show associations between various factors of the business operations. They entail comparison of income statement and balance sheet’s elements. These ratios are grouped into four distinct categories; liquidity ratios (Quick and current ratios), profitability ratios (ROE and ROA), leverage (debt-equity ratio and debt-to-assets ratio) and investors’ ratios (EPS and P/E). These ratios are beneficial since they summarize the financial statements and make it easy for investors to understand but they do have some drawbacks like use of irrelevant information in making future decision and different users of accounting information use different terms to depict financial information among others. Therefore, investors should be aware that ratios are good measures but they cannot be used solely to make financial decision as a result of these drawbacks. Thus, investors should seek other measures like non-financial analysis by looking at management style and experience, and morale of the employees among others.

Security analysts and investors frequently use ratios to evaluate the weaknesses and strengths of various firms. Ratio analysis is important in analyzing financial statements which is a crucial step before investing in any firm since it quantifies the firm’s performance in various factors like the firm’s ability to be profitable, ability of the firm to pay debt (liquidity of the firm), stability of the firm in paying long-term debt as well as the ability of the company to manage its assets (efficiency). Ratios normally compare the firm’s performance in a certain period and against other firms in the industry in order to determine the firm’s weaknesses and strengths and for investors or managers to take suitable investment and financing decisions (Liu and O’Farrell, 2009).

It is hard to deduce the firm’s performance from two or three simple figures. Nonetheless, in practice some diverse ratios are frequently calculated during strategic planning activities and in general because financial ratios do offer information on relative performance of the firm. Particularly, careful evaluation of a mixture of the ratios might assist in making a distinction between companies that will in the end not succeed from those companies that will succeed. Therefore, ratio analysis is discussed, and some benefits and limitations linked with their usage are emphasized. Lastly, ratios are more relevant when used to evaluate firms in the same industry (Nd.edu, 2010).

For survival, companies should be able to pay creditors and other short-term obligations. In this case, firm should be concerned with its liquidity by use of measures like quick ratio and current ratio. The major difference between these two ratios is that, the former does not use stock while the latter does. Quick ratio is a conventional standard; if it is more than one it implies that the firm is not facing liquidity risk and that is it can be able to pay current liabilities. And if not more than one but current ratio is above one, the firm’s status is more composite. In such a situation, valuation of stocks and stock turnover are clearly crucial (Nd.edu, 2010).

Stock valuation methods life LIFO and FIFO may contaminate current ratio. This is because firms use different methods when valuing stocks, which may overvalue or undervalue the stocks, making it hard to compare firms using current ratio. This means that quick ratio is the most preferred liquidity ratio (Nd.edu, 2010). Consider Hyatt Hotel Corporation’s quick ratio of 2010 and 2009, the firm’s liquidity position decline in 2010, implying that the firm was using more of current liabilities in 2010 compared with 2009. Compared to other firms in the industry like Red Lion Hotels and Intercontinental Hotels Group (IHG), Hyatt is more liquid than its competitors who are facing liquidity risk since the ratio is less than one as shown by Table 1.

Companies are funded by mixture of equity and debt and the optimal capital structure depends on the tax policy, corporate risk and bankruptcy costs. Two measures are used, debt-equity ratio and debt-to-assets ratio (Nd.edu, 2010).

Just like liquidity ratios, leverage ratios pose some issues in interpretation and measurement. In this case equity and assets are normally measured through book value in financial statements, the book value does not depict the company’s market value or value the creditors would receive if firm is liquidated (Nd.edu, 2010).

Ratios like the debt-to-equity ratios differ significantly crossways industries due to industry’s characteristics and environment.

A utility firm that is more stable can operate comfortably with comparatively superior debt-equity ratio while a cyclical firm like recreational vehicles manufacturer normally requires lower ratio (Nd.edu, 2010).

Frequently analysts use debt-equity ratio to establish the capability of the firm to generate additional finances from capital market. A firm with significant debt is frequently considered to have less additional-funding capacity. In reality, the overall funding capacity of the firm possibly depends on the new product’s quality that the firm is wishing to pursue with its capital structure. Nonetheless, given bankruptcy threat and costs, a superior debt-equity ratio might make future refinance hard (Nd.edu, 2010).

For instance, debt-equity ratio of Hyatt declined in 2010 indicating a reduction in the gearing level of the firm compared to the year 2009. Compared to its competitors, Red Lion and IHG, Hyatt is less geared and IHG is highly geared among the three firms as it is more than 100%. This implies that IHG is facing high financial risks while Hyatt’s financial risk is very low as shown by Table 2.

ROE and ROA are measures of firm’s profitability and are widespread in firms. Equity and assets as utilized in these ratios are book values. Therefore, if fixed assets were bought in the past three years at a lower price, this means that the present performance of the firm might be overstated through the utilization of past information. As a consequence, accounting returns of the investment are normally not correlated well with real economic project’s IRR (Nd.edu, 2010).

It is hard to use these two ratios in merger deals to measure the firms’ performance. Assume we have a firm X that used to earn net profit of $1,000 on the assets with book value of $2,000, for a large 50% as ROA. This firm is currently acquired by another firm Y that transfer the additional assets to its balance sheet at the buying price, presuming that the transaction is treated through the use of accounting method of purchase. Actually, the purchase price will be more than $2,000, higher than the assets book value, for a possible acquirer must pay higher price for privilege of gaining $1,000 on an ordinary basis.

Assume further the firm Y pays $3,000 for X’s assets. After the purchase, it will emerge that X’s returns have decreased, Firm X continues to make $1,000 but currently the asset base is at $3,000, and thus the ROA reduces to 33.33%. In reality, ROA might reduce due to other factors like rise in depreciation of the additional assets obtained. However, nothing has happened to net income of the company but only its accounting has changed and not the firm’s performance (Nd.edu, 2010).

ROE and ROA also have another problem in that analyst tend to concentrate on the single years performance, years that might be idiosyncratic. On average, one must evaluate these ratios over some years through use of average to separate returns that are idiosyncratic and attempt to identify patterns (Nd.edu, 2010).

For example, Hyatt’s ROE and ROA indicate that the firm’s profitability increased in 2010 implying that the firm’s efficiency in managing production costs, operating costs and cost of sales as well as assets had improved, while IHG was the most profitable firm among the three firms with, Red Lion being the least profitable firm as shown on Table 3.

These ratios are determined from the performance of the stock market and they include; P/E, Dividend Yield and EPS. EPS is widely used amongst the three ratios. In reality, it is shown on financial statements of the listed firms. EPS indicates how much each share invested in the firm has earned. This means that it is not a useful statistics since it does not show how many fixed assets the company utilized to generate those incomes, and thus nothing on profitability. It also does not show how much the shareholder has paid for each share invested in the firm for rights over the annual income. In addition, the accounting principles used to determine the income might alter these ratios and treatment of stock is also challenging (Nd.edu, 2010).

P/E ratio is also used and it is reported mainly in the daily newspapers. P/E ratio that is high indicates that the investors deem that the firm’s future prospects are superior to its present performance. They are paying more for every share than company’s present income warrant. And still the income is treated in different ways in diverse accounting practices (Nd.edu, 2010).

For example, in 2010 the EPS of Hyatt increased from 0.28 to 0.29 this means that for every share invested in the firm generated $0.29 of the firm’s earnings. Compared to competitors, Red Lion has the least EPS while IHG has the highest. The Hyatt’s P/E indicates the investors in 2009 and 2010 would take 106.46 and 157.79 years to recover their initial investment in shares from the earnings generated by that investment in the firm respectively, while its competitors’ investors will take less years for them to recover their initial investment as shown by Table 4.

Financial analysis involving ratios is a helpful tool for the users of the financial statements. Ratio analysis has some advantages that include; first, they simplify firm’s financial statements and also emphasize significant information in straightforward form quickly. Thus a user of the firm’s financial statements can judge the firm by only looking at some figures instead of examining the entire financial statements. Finally, the analysis assists in comparing firms of varying magnitude within the industry and can be used in comparing one firm financial performance over a particular period of time, normally referred as trend analysis (Accountingexplained.com, 2011).

On the other hand, the analysis poses some disadvantages in that information from the financial accounting is influenced by assumptions and estimates. Accounting standards let varying accounting policies that damages comparability and thus in such circumstances ratio analysis is used less. The ratio analysis describes relationships between historical information while the users are mostly concerned on the present and the future information. Different firms operate in diverse industries with diverse environmental conditions like market structure, and regulation among others. These factors are so important in that an evaluation of the two firms from dissimilar industries may be misleading (Accountingexplained.com, 2011).

For instance, a Chinese firm’s financial ratios might be exposed to misunderstanding by an investor from US as a result of variations in the accounting principles, institutional and culture environments, economic environments and business practices. China adopted IFRS ever since 2007 whilst firms in the United States are still applying U.S. GAAP to report accounting information (Liu and O’Farrell, 2009). The culture of China is centred on the relationships while culture of America is centred on the individuals. In addition the variation between collectivists and individualists, people of China have a tendency of being risk-adverse and conservative.

China is a socialism nation in evolution from the planned economy to the market economy while US on the other hand, is a nation having a market capitalism. These two nations have different GDP growth with China having the highest compared to US. Such variations may decrease the comparability and comprehension of information from financial accounting. The Chinese firms may be found to have lower Asset Turnover ratio probably as a result of firm’s high growth rate, superior Average Collection Period probably as a result of overstated debtors account and the requirement to guarantee steady employment, and a lower Debt to Net Worth ratio probably as a result of risk averseness nature of the Chinese individual investors (Liu and O’Farrell, 2009).

These disadvantages stirred researchers to investigate and make use of methods such as negative examination elimination, trimming, square root, logarithmic, logit as well as utilizing rank transformation in order to attain more projective independent variables (Bahiraie, 2008).

During utilization of ratios managers are more concerned with misinforming than informing. Managers therefore seek to reduce discretionary costs like advertising, training, research and maintenance among others, with the aim of increasing net profit whilst having a negative effect on the future income potential. New management might likewise write-down assets value to decrease the amortization and depreciation charges for future financial years. An entrepreneur might evade restocking inventory at some point in time especially before the end of the financial year in order to raise the firm’s current ratio. Short-term payment of the current liabilities or debt just before the end of the financial year will accomplish similar outcome. Retained earnings may be corrected for the future stock price decrease and afterwards recorded as net income.

Frequently an assessment of a sequence of the annual statements instead of one year will emphasize such practices. More excessive practices are normally avoided by companies that are required to answer to the regulatory agencies in order to be listed on the stock market or exchange (Best, 2009).

Ratios are normally utilized in strategic planning. These ratios may be manipulated through opportunistic practices of accounting. Nonetheless, taken collectively and utilized sensibly, they might assist in identifying companies or business divisions in particular problem. And finding new ventures that are profitable needs more effort. Therefore, investors should carry out their own analyses to determine which firm to invest in. Due to limitations of these ratios, the investors should also consider the non-financial analysis like the leadership style, morale of employees and experience among others.

Accountingexplained.com. (2011). Advantages and limitations of financial ratio analysis. Web.

Bahiraie, A., Ibrahim, N., Mohd, I. and Azhar, A. (2008). Financial Ratios: A new geometric transformation. International Research Journal of Finance and Economic , 20:165-171.

Best, B. (2009). The uses of financial statements . Web.

Liu, C. and O’Farrell, G. (2009). China and U.S. financial ratio comparison. International Journal of Business, Accounting, and Finance , 3(2): 1-13.

Nd.edu. (2010). Financial ratio analysis . Web.

Cite this paper

- Chicago (N-B)

- Chicago (A-D)

StudyCorgi. (2022, May 13). Ratio and Financial Statement Analysis. https://studycorgi.com/ratio-and-financial-statement-analysis/

"Ratio and Financial Statement Analysis." StudyCorgi , 13 May 2022, studycorgi.com/ratio-and-financial-statement-analysis/.

StudyCorgi . (2022) 'Ratio and Financial Statement Analysis'. 13 May.

1. StudyCorgi . "Ratio and Financial Statement Analysis." May 13, 2022. https://studycorgi.com/ratio-and-financial-statement-analysis/.

Bibliography

StudyCorgi . "Ratio and Financial Statement Analysis." May 13, 2022. https://studycorgi.com/ratio-and-financial-statement-analysis/.

StudyCorgi . 2022. "Ratio and Financial Statement Analysis." May 13, 2022. https://studycorgi.com/ratio-and-financial-statement-analysis/.

This paper, “Ratio and Financial Statement Analysis”, was written and voluntary submitted to our free essay database by a straight-A student. Please ensure you properly reference the paper if you're using it to write your assignment.

Before publication, the StudyCorgi editorial team proofread and checked the paper to make sure it meets the highest standards in terms of grammar, punctuation, style, fact accuracy, copyright issues, and inclusive language. Last updated: September 6, 2022 .

If you are the author of this paper and no longer wish to have it published on StudyCorgi, request the removal . Please use the “ Donate your paper ” form to submit an essay.

Ratio Analysis

1. Introduction to Ratio Analysis

Ratio analysis is a widely used tool of financial analysis. It is defined as the systemic use of ratio to interpret the financial statements so that the strengths and weaknesses of a firm, as well as its historical performance and current financial condition, can be determined.

Ratios make the related information comparable. A single figure by itself has no meaning but when expressed in terms of related figures it yields significant inferences. Thus ratios are relative figures reflecting the relationship between related variables.

Their use, as tools of financial analysis, involves their comparison as single ratios like absolute figures are not of much use. A ratio is quotient of two numbers and is an expression of relationship between the figures which are not of much use.

A ratio is a quotient of two numbers and is an expression of relationship between the figures or two amounts.

ADVERTISEMENTS:

It indicates a quantitative relationship which is used for a qualified judgment and decision making. The relationship between two accounting figures is known as accounting ratio. These may be compared with the previous year or base year ratios of the same firm. Ratios indicate the relationship between profits and capital employed. Ratios may be expressed in 3 forms – (a) as quotient 1:1 or 2:1 etc.; (b) as a rate, i.e., inventory turnover as a number of times in year and (c) as a percentage. Ratio analysis is useful to shareholders, creditors and executives of the company.

2. Care in Use of Ratios

To get better result ratio analysis is required to be done with care as several factors affect the efficacy of ratios.

These factors are given below:

(1) Type of business under consideration affects the ratios and conclusions drawn from them. For example a high ratio of debt to net worth can be expected of a public utility company operating with large fixed assets with social benefits consideration.

(2) Seasonal character of the business affects ratios for a particular type of industry or enterprise. For example inventory to sales ratio for a grain merchant during the peak season has a different meaning and is supposed to be much higher than during other periods of the same year.

(3) Quality of assets also affects the ratio analysis and gives different interpretations to different business enterprises.

Current assets to current liabilities ratio mostly 2:1 is considered more satisfactory for a liquid position of the company but if with the same proportion of assets acid test ratio is calculated it may give a different result and may depict the unsatisfactory proportion of availability of liquid funds with the company to meet its most urgent and pressing obligation.

(4) Adequacy of data is another consideration for comparison of particular factors with each other. For example average collection period for Bill Receivable for a particular month may differ to those with other months or the average of the year. Another consideration would be whether Bill Receivable has been properly valued for a particular period as over valuation may render the ratio incomparable.

(5) Modification of ratios reflects only the past performance and must be modified by future trends of business.

(6) Interpretation of ratios should be relied upon in isolation and should be considered with accounting documents for interpretations.

(7) Non-financial data ratios based on financial data of firms should be considered with non-financial data to supplement the financial ratios that give better interpretation.

3. Types of Ratios

Ratios can be broadly classified into four groups:

1. Liquidity ratios;

2. Capital Structure / Leverage ratios;

3. Profitability ratios and

4. Activity ratios.

1. Liquidity Ratios:

Liquidity is a prerequisite for the very survival of a business unit. Liquidity represents the ability of the business concern to meet short-term obligations when they fall due for payment. Hence the maintenance of adequate liquidity in any business concern cannot be over emphasized.

The liquidity ratio measures the ability of the business concern to meet its short-term obligations and reflects the short-term solvency of the unit.

Important Liquidity Ratios:

2. Capital Structure/Leverage Ratios:

The second category of financial ratio is Leverage or Capital structure ratios. The short-term Creditors would use leverage ratios for ascertaining the current financial position of the business unit.

The long-term would use leverage or capital structure ratio to examine the long term solvency of the business unit. The leverage ratio reflects the capacity of the business unit. The leverage ratios reflect on the capacity of the business unit to assure long term creditor as regards to periodic payment of interest during the period of the loan as well as repayment of principal on maturity.

There are two aspects of the long term solvency of a unit as reflected in its policy to repay the principal on maturity and pay interest at periodic intervals. These two aspects are mutually dependent and interrelated and give rise to two types of leverage ratios.

The first type of leverage ratios which are based on the relationship between borrowed funds and owner’s capital and computed from the balance sheet include many variations such as

(i) debt equity ratio,

(ii) proprietary ratio,

(iii) equity-asset ratio.

The second type of leverage ratio which are also referred to as “Coverage ratios” computed from the Profit and Loss Account include many variations such as

(i) interest coverage ratio,

(ii) dividend coverage ratio and

(iii) total fixed charges coverage ratio.

Important Leverage/Capital Structure Ratios:

3. Profitability Ratios:

The Profitability of any organization is very essential and serves as an incentive to achieve efficiency. Thus the management of any business organizations strives to measure the operating efficiency of that organization to ensure optimum profitability on its investment. The profitability ratios are designed to measure the profitability of any organization.

In other words these ratios indicate the units’ efficiency of operation. Profitability ratios can be divided into two categories i.e. showing profitability either in relation to sales or in relation to investments.

Important Profitability Ratios:

4. Activity/Turnover/Efficiency Ratios:

The last category of ratios is the activity ratios. They are also known as the efficiency or turnover ratios. Such ratios are concerned with measuring the efficiency in asset management. The efficiency with which assets are managed / used is reflected in the speed and rapidity with which they are converted into sales.

Thus the activity ratios are a test of relationship between sales / cost of goods sold and assets.

Depending upon the type of asset, activity ratios may be (i) inventory / stock turnover, (ii) receivable / debtor’s turnover and (iii) total assets turnover. The first of these indicates the number of times inventory is replaced during the year, of how quickly the goods are sold. It is a test of efficiency inventory management. The second category of turnover ratio is indicative of the efficiency of receivables management as it shows how quickly trade goods are sold. It reveals the efficiency in managing and utilizing the total assets.

Important Activity / Turnover / Efficiency Ratios:

4. Advantages of Ratio Analysis

The special advantage of working out accounting ratios is that performance and financial position can be properly judged.

Following are some important advantages of ratio analysis:

(i) Decision-making process.

(ii) Diagnosis of financial ills.

(iii) Evaluation of financial performances

(iv) Short and long term planning.

(v) Study of financial trends;

5. Limitations of Ratio Analysis

1. Reliability of ratio depends upon the reliability of the original data / information collected.

2. Increases, decreases and constant changes in the price distort the comparison over period of years

3. The benefits of ratio analysis depends on correct interpretation. Many times it is observed that due to small errors in original data it leads to false conclusions.

4. A ratio-analysis is not an ultimate yardstick for assessing the performance of the firm.5. If there is window-dressing then the ratios calculated will fail to give the correct picture and it will be mismanagement.

Related Articles:

- Ratios: Classification and Computation

- Analysis and Interpretation of Financial Statements

- Leverage Analysis

- Funds Flow Analysis

- List of Commerce Articles

Ratio Analysis

Ratio analysis is referred to as the study or analysis of the line items present in the financial statements of the company. It can be used to check various factors of a business such as profitability, liquidity, solvency and efficiency of the company or the business.

Ratio analysis is mainly performed by external analysts as financial statements are the primary source of information for external analysts.

The analysts very much rely on the current and past financial statements in order to obtain important data for analysing financial performance of the company. The data or information thus obtained during the analysis is helpful in determining whether the financial position of a company is improving or deteriorating.

Also see: Advantages and Disadvantages of Ratio Analysis

Categories of Ratio Analysis

There are a lot of financial ratios which are used for ratio analysis, for the scope of Class 12 Accountancy students. The following groups of ratios are considered in this article, which are as follows:

1. Liquidity Ratios: Liquidity ratios are helpful in determining the ability of the company to meet its debt obligations by using the current assets. At times of financial crisis, the company can utilise the assets and sell them for obtaining cash, which can be used for paying off the debts.

Some of the most commonly used liquidity ratios are quick ratio, current ratio, cash ratio, etc. The liquidity ratios are used mostly by creditors, suppliers and any kind of financial institutions such as banks, money lending firms, etc for determining the capacity of the company to pay off its obligations as and when they become due in the current accounting period.

2. Solvency Ratios: Solvency ratios are used for determining the viability of a company in the long term or in other words, it is used to determine the long term viability of an organisation.

Solvency ratios calculate the debt levels of a company in relation to its assets, annual earnings and equity. Some of the important solvency ratios that are used in accounting are debt ratio, debt to capital ratio, interest coverage ratio, etc.

Solvency ratios are used by government agencies, institutional investors, banks, etc to determine the solvency of a company.

3. Activity Ratio: Activity ratios are used to measure the efficiency of the business activities. It determines how the business is using its available resources to generate maximum possible revenue.

These ratios are also known as efficiency ratios. These ratios hold special significance for business in a way that whenever there is an improvement in these ratios, the company is able to generate revenue and profits much efficiently.

Some of the examples of activity or efficiency ratios are asset turnover ratio, inventory turnover ratio, etc.

4. Profitability ratios: The purpose of profitability ratios is to determine the ability of a company to earn profits when compared to their expenses. A better profitability ratio shown by a business as compared to its previous accounting period shows that business is performing well.

The profitability ratio can also be used to compare the financial performance of a similar firm, i.e it can be used for analysing competitor performance.

Some of the most used profitability ratios are return on capital employed, gross profit ratio, net profit ratio, etc.

Use of Ratio Analysis

Ratio analysis is useful in the following ways:

1. Comparing Financial Performance: One of the most important things about ratio analysis is that it helps in comparing the financial performance of two companies.

2. Trend Line: Companies tend to use the activity ratio in order to find any kind of trend in the performance. Companies use data from financial statements that is collected from financial statements over many accounting periods. The trend that is obtained can be used for predicting the future financial performance.

3. Operational Efficiency: Financial ratio analysis can also be used to determine the efficiency of managing the asset and liabilities. It helps in understanding and determining whether the resources of the business is over utilised or under utilised.

This concludes our article on the topic of Ratio Analysis, which is an important topic in Class 12 Accountancy for Commerce students. For more such interesting articles, stay tuned to BYJU’S.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Your Mobile number and Email id will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Request OTP on Voice Call

Post My Comment

Register with BYJU'S & Download Free PDFs

Register with byju's & watch live videos.

- Search Search Please fill out this field.

- Building Your Business

- Operations & Success

What Is Financial Ratio Analysis?

Overview, Definition, and Calculation of Financial Ratios

Types of Financial Ratios

- How Financial Ratio Analysis Works

Interpretation of Financial Ratio Analysis

Who uses financial ratio analysis, frequently asked questions (faqs).

Getty Images/Trevor Williams

Financial ratio analysis uses the data contained in financial documents like the balance sheet and statement of cash flows to assess a business's financial strength. These financial ratios help business owners and average investors assess profitability, solvency, efficiency, coverage, market value, and more.

Key Takeaways

- Financial ratio analysis assesses the performance of the firm's financial functions of liquidity, asset management, solvency, and profitability.

- Financial ratio analysis is a powerful analytical tool that can give the business firm a complete picture of its financial performance on both a trend and an industry basis.

- The information gleaned from a firm's financial statements by ratio analysis is useful for financial managers, competitors, and average investors.

- Financial ratio analysis is only useful if data is compared to past performance or to other companies in the same industry.

Financial ratios are useful tools that help business managers, owners, and potential investors analyze and compare financial health. They are one tool that makes financial analysis possible across a firm's history, an industry, or a business sector.

Financial ratio analysis uses the data gathered from these ratios to make decisions about improving a firm's profitability, solvency, and liquidity.

There are six categories of financial ratios that business managers normally use in their analysis. Within these six categories are multiple financial ratios that help a business manager and outside investors analyze the financial health of the firm.

It's important to note that financial ratios are only meaningful in comparison to other ratios for different time periods within the firm. They can also be used for comparison to the same ratios in other industries, for other similar firms, or for the business sector.

Liquidity Ratios

The liquidity ratios answer the question of whether a business firm can meet its current debt obligations with its current assets. There are three major liquidity ratios that business managers look at:

- Working capital ratio : This ratio is also called the current ratio (current assets - current liabilities). These figures are taken off the firm's balance sheet. It measures whether the business can pay its short-term debt obligations with its current assets.

- Quick ratio: This ratio is also called the acid test ratio (current assets - inventory/current liabilities). These figures come from the balance sheet. The quick ratio measures whether the firm can meet its short-term debt obligations without selling any inventory.

- Cash ratio : This liquidity ratio (cash + cash equivalents/current liabilities) gives analysts a more conservative view of the firm's liquidity since it uses only cash and cash equivalents, such as short-term marketable securities, in the numerator. It indicates the ability of the firm to pay off all its current liabilities without liquidating any other assets.

Efficiency Ratios

Efficiency ratios, also called asset management ratios or activity ratios, are used to determine how efficiently the business firm is using its assets to generate sales and maximize profit or shareholder wealth. They measure how efficient the firm's operations are internally and in the short term. The four most commonly used efficiency ratios calculated from information from the balance sheet and income statement are:

- Inventory turnover ratio: This ratio (sales/inventory) measures how quickly inventory is sold and restocked or turned over each year. The inventory turnover ratio allows the financial manager to determine if the firm is stocking out of inventory or holding obsolete inventory.

- Days sales outstanding: Also called the average collection period (accounts receivable/average sales per day), this ratio allows financial managers to evaluate the efficiency with which the firm is collecting its outstanding credit accounts.

- Fixed assets turnover ratio: This ratio (sales/net fixed assets) focuses on the firm's plant, property, and equipment, or its fixed assets, and assesses how efficiently the firm uses those assets.

- Total assets turnover ratio: The total assets turnover ratio (sales/total assets) rolls the evidence of the firm's efficient use of its asset base into one ratio. It allows analysts to gauge how efficiently the asset base is generating sales and profitability.

Solvency Ratios

A business firm's solvency, or debt management, ratios allow the analyst to appraise the position of the business firm's debt financing or financial leverage that they use to finance their operations. The solvency ratios gauge how much debt financing the firm uses as compared to either its retained earnings or equity financing. There are two major solvency ratios:

- Total debt ratio : The total debt ratio (total liabilities/total assets) measures the percentage of funds for the firm's operations obtained by a combination of current liabilities plus its long-term debt.

- Debt-to-equity ratio : This ratio (total liabilities/total assets - total liabilities) is most important if the business is publicly traded. The information from this ratio is essentially the same as from the total debt ratio, but it presents the information in a form that investors can more readily utilize when analyzing the business.

Coverage Ratios

The coverage ratios measure the extent to which a business firm can cover its debt obligations and meet the associated costs. Those obligations include interest expenses, lease payments, and, sometimes, dividend payments. These ratios work with the solvency ratios to give a financial manager a full picture of the firm's debt position. Here are the two major coverage ratios:

- Times interest earned ratio: This ratio (earnings before interest and taxes (EBIT)/interest expense) measures how well a business can service its total debt or cover its interest payments on debt.

- Debt service coverage ratio: The DSCR (net operating income/total debt service charges) is a valuable summary ratio that allows the firm to get an idea of how well the firm can cover all of its debt service obligations.

Profitability Ratios

Profitability ratios are the summary ratios for the business firm. When profitability ratios are calculated, they sum up the effects of liquidity management, asset management, and debt management on the firm. The four most common and important profitability ratios are:

- Net profit margin: This ratio (net income/sales) shows the profit per dollar of sales for the business firm.

- Return on total assets (ROA): The ROA ratio (net income/sales) indicates how efficiently every dollar of total assets generates profit.

- Basic earning power (BEP): BEP (EBIT/total assets) is similar to the ROA ratio because it measures the efficiency of assets in generating sales. However, the BEP ratio makes the measurement free of the influence of taxes and debt.

- Return on equity (ROE): This ratio (net income/common equity) indicates how much money shareholders make on their investment in the business firm. The ROE ratio is most important for publicly traded firms.

Market Value Ratios

Market Value Ratios are usually calculated for publicly held firms and are not widely used for very small businesses. Some small businesses are, however, traded publicly. There are three primary market value ratios:

- Earnings per share (EPS): As the name implies, this measurement conveys the business's earnings on a per-share basis. It is calculated by dividing the net income by the outstanding shares of common stock.

- Price/earnings ratio (P/E): The P/E ratio (stock price per share/earnings per share) shows how much investors are willing to pay for the stock of the business firm per dollar of profits.

- Price/cash flow ratio: A business firm's value is dependent on its free cash flows. The price/cash flow ratio (stock price/cash flow per share) assesses how well the business generates cash flow.

- Market/book ratio: This ratio (stock price/book value per share) gives the analyst another indicator of how investors view the value of the business firm.

- Dividend yield: The dividend yield divides a company's annual dividend payments by its stock price to help investors estimate their passive income. Dividends are typically paid quarterly, and each payment can be annualized to update the dividend yield throughout the year.

- Dividend payout ratio: The dividend payout ratio is similar to the dividend yield, but it's relative to the company's earnings rather than the stock price. To calculate this ratio, divide the dollar amount of dividends paid to investors by the company's net income.

How Does Financial Ratio Analysis Work?

Financial ratio analysis is used to extract information from the firm's financial statements that can't be evaluated simply from examining those statements. Ratios are generally calculated for either a quarter or a year.

To calculate financial ratios, an analyst gathers the firm's balance sheet, income statement, and statement of cash flows, along with stock price information if the firm is publicly traded. Usually, this information is downloaded to a spreadsheet program.

Small businesses can set up their spreadsheet to automatically calculate each of these financial ratios.

One ratio calculation doesn't offer much information on its own. Financial ratios are only valuable if there is a basis of comparison for them. Each ratio should be compared to past periods of data for the business. The ratios can also be compared to data from other companies in the industry.

It is only after comparing the financial ratios to other time periods and to the companies' ratios in the industry that an analyst can draw conclusions about the firm performance.

For example, if a firm's debt-to-asset ratio for one time period is 50%, that doesn't tell a useful story unless it's compared to previous periods, especially if the debt-to-asset ratio was much lower or higher historically. In this scenario, the debt-to-asset ratio shows that 50% of the firm's assets are financed by debt. The financial manager or an investor wouldn't know if that is good or bad unless they compare it to the same ratio from previous company history or to the firm's competitors.

Performing an accurate financial ratio analysis and comparison helps companies gain insight into their financial position so that they can make necessary financial adjustments to enhance their financial performance.

There are other financial analysis techniques that owners and potential investors can combine with financial ratios to add to the insights gained. These include analyses such as common size analysis and a more in-depth analysis of the statement of cash flows.

Several stakeholders might need to use financial ratio analysis:

- Financial managers : Financial managers must have the information that financial ratio analysis imparts about the performance of the various financial functions of the business firm. Ratio analysis is a valuable and powerful financial analysis tool.

- Competitors : Other business firms find the information about the other firms in their industry important for their own competitive strategy.

- Investors : Current and potential investors (whether publicly traded or financed by venture capital) need the financial information gleaned from ratio analysis to determine whether or not they want to invest in the business.

What are 5 key financial ratios?

Five of the most important financial ratios for new investors include the price-to-earnings ratio, the current ratio, return on equity, the inventory turnover ratio, and the operating margin.

Why is financial ratio analysis important?

Financial ratio analysis quickly gives you insight into a company's financial health. Rather than having to look at raw revenue and expense data, owners and potential investors can simply look up financial ratios that summarize the information they want to learn.

Want to read more content like this? Sign up for The Balance’s newsletter for daily insights, analysis, and financial tips, all delivered straight to your inbox every morning!

Wells Fargo. " 5 Ways To Improve Your Liquidity Ratio ."

Morningstar. " Efficiency Ratios ."

OpenStax. " Principles of Finance: 6.4 Solvency Ratios ."

YCharts. " Times Interest Earned ."

Austin Water. " Financial Policies Update Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) ."

Edward Lowe Foundation. " How To Analyze Profitability ."

Pamela P. Peterson, Pamela Peterson Drake, Frank J. Fabozzi, " Analysis of Financial Statements ," Pages 76-77. Wiley, 1999.

Nasdaq. " Return on Equity (ROE) ."

OpenStax. " Principles of Finance: 6.5 Market Value Ratios ."

OpenStax. " Principles of Finance: 11.1 Multiple Approaches to Stock Valuation ."

Rodney Hobson. " The Dividend Investor ." Harriman House, 2012.

Corporate Finance Institute. " Financial Ratios ."

Edward Lowe Foundation. " How To Analyze Your Business Using Financial Ratios ."

The Using of Ratio Analysis Essay

- To find inspiration for your paper and overcome writer’s block

- As a source of information (ensure proper referencing)

- As a template for you assignment

Introduction

Ratio analysis is one of the tools that can be used to analyze the performance of a Healthcare Institution. One computes the ratios using standard ratios then compares the results with those of the previous year. Results can be compared with similar healthcare institutions too. This paper will apply ratio analysis to the financial statements of The Medical College of Georgia Health-centre. The subject of the analysis is the financial statements of 2006 and 2007. The focus is on two major categories of ratios: asset and revenue ratios (Reijers, 2005).

Asset Ratios

Asset ratios measure the efficiency with which the institution has used its assets over the period in question. The Asset Turnover ratio is the major ratio in this category. The debt to asset ratio focuses on the MCG’s debt about its total assets. The final category is the liquidity ratios. This category consists of the current and quick ratios. These measure the ability of MCG to pay up its short-term debts promptly. The short-term debts would include salaries and the purchase of medical supplies.

The Total Debt to Asset ratio expresses MCG’s capital structure in percentage form. The debt finance has reduced slightly from 23.6% in 2006 to 23.1% in 2007. This may be because a proportion of the health center’s long-term loans were repaid. It could also be that the company acquired more assets in 2007 but retained the same level of debt finance. A lower debt to asset ratio is a good sign for investors.

There was a drop in the current ratio from 3 in 2006 to 2.5 in 2007. This is not a good sign as it shows decreasing ability to meet current liabilities and short-term commitments. The current ratio shows how easily the company can meet such short-term obligations. Failure to do so could result in I liquidity and operational problems. In the case of MCG, it is important to note that the hospital cannot run without supplies. They should therefore be able to purchase them when needed. Management needs to investigate the falling current ratio (Finkler & Ward, 2006).

The Quick Ratio followed the Current Ratio’s trend. It dropped from 2.8 in 2006 to 2.4 in 2007. This could be due to an increase in current liabilities or a decrease in current assets. Like the current ratio, this is an important indicator of MCG’s liquidity and should be investigated further (Finkler & Ward, 2006).

The asset turnover ratio tells of the hospital’s efficiency in using its assets. It has been constant in the past two years. This shows that the hospital is using its assets at the same rate to generate profit. The result of 250% shows high efficiency. Management should try to keep that up or improve on their efficiency.

Revenue Ratios

Gross Profit Margin has increased from 38.8% to 40.3%. In this question, the cost of salaries was taken as the cost of goods sold. This is because a hospital is a service organization. It, therefore, means that the salaries decreased in 2007. Alternatively, the hospital might have made more profit while paying the same salaries as in 2006.

The Net Profit Margin also increased slightly from 3.11% to 3.5%. This shows that MCG managed its operating expenses better in 2007. The decrease shows higher efficiency. It could also mean that more revenue was earned with the same level of expenses. Whichever way one looks at it, it is an improvement.

The Non-Operating Revenue ratio indicates what percentage of MCG’s revenue was derived from sources other than providing health services. In 2006, it was 11.55% while in 2007 it was 11.02%. This was a slight decrease. It means that the revenue from non-operating activities in proportion to total revenue decreased.

The Operating Revenue ratio is the opposite of the Non-Operating Revenue ratio. It shows the proportion of operating revenue. This ratio increased from 88.5% to 88.9% in 2007. It indicates that MCG is getting more revenue from its core activity. This is the provision of health services.

Ratio analysis can be quite helpful to health facilities. However, several pitfalls need to be avoided. First, it is important to note that ratio analysis is useless without comparative information. Assuming we had only the 2007 financial statements, then ratio analysis would be useless. The figures involved in the analysis are not always accurate. Hence, there may be mistakes in the results. Finally, the results need further explanation, as there may be reasons as to why they are good or bad. However, the usefulness of ratio analysis cannot be understated.

Finkler, S., & Ward, D. (2006). Accounting Fundamentals for Health Care Management. Chicago: Jones and Bartlette Publishers.

Reijers, H. (2005). Best practices in business process redesign: an overview and qualitative evaluation of successful redesign heuristics. Omega , 33 (4), 283-306.

- Adolescent Pregnancy Rate Analysis

- Endocrine, Metabolic, and Hematologic Disorders

- Folic Acid Supplements and Psychotic Medication During Pregnancy

- Transformational Changes to Promote & Create Learning Organizations

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention Program for Tanzania

- The King Edgar Hospital’s National Health Service Trust

- The US and the Taiwan Healthcare Systems: Comparative Analysis

- Use of Abbreviations in the Healthcare Field

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2022, March 25). The Using of Ratio Analysis. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-using-of-ratio-analysis/

"The Using of Ratio Analysis." IvyPanda , 25 Mar. 2022, ivypanda.com/essays/the-using-of-ratio-analysis/.

IvyPanda . (2022) 'The Using of Ratio Analysis'. 25 March.

IvyPanda . 2022. "The Using of Ratio Analysis." March 25, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-using-of-ratio-analysis/.

1. IvyPanda . "The Using of Ratio Analysis." March 25, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-using-of-ratio-analysis/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "The Using of Ratio Analysis." March 25, 2022. https://ivypanda.com/essays/the-using-of-ratio-analysis/.

- Methodology

- Open access

- Published: 31 May 2024

Survival analysis for AdVerse events with VarYing follow-up times (SAVVY): summary of findings and assessment of existing guidelines

- Kaspar Rufibach ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2634-1167 1 ,

- Jan Beyersmann 2 ,

- Tim Friede 3 ,

- Claudia Schmoor 4 &

- Regina Stegherr 5

Trials volume 25 , Article number: 353 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

132 Accesses

2 Altmetric

Metrics details

The SAVVY project aims to improve the analyses of adverse events (AEs) in clinical trials through the use of survival techniques appropriately dealing with varying follow-up times and competing events (CEs). This paper summarizes key features and conclusions from the various SAVVY papers.

Summarizing several papers reporting theoretical investigations using simulations and an empirical study including randomized clinical trials from several sponsor organizations, biases from ignoring varying follow-up times or CEs are investigated. The bias of commonly used estimators of the absolute (incidence proportion and one minus Kaplan-Meier) and relative (risk and hazard ratio) AE risk is quantified. Furthermore, we provide a cursory assessment of how pertinent guidelines for the analysis of safety data deal with the features of varying follow-up time and CEs.

SAVVY finds that for both, avoiding bias and categorization of evidence with respect to treatment effect on AE risk into categories, the choice of the estimator is key and more important than features of the underlying data such as percentage of censoring, CEs, amount of follow-up, or value of the gold-standard.

Conclusions

The choice of the estimator of the cumulative AE probability and the definition of CEs are crucial. Whenever varying follow-up times and/or CEs are present in the assessment of AEs, SAVVY recommends using the Aalen-Johansen estimator (AJE) with an appropriate definition of CEs to quantify AE risk. There is an urgent need to improve pertinent clinical trial reporting guidelines for reporting AEs so that incidence proportions or one minus Kaplan-Meier estimators are finally replaced by the AJE with appropriate definition of CEs.

Peer Review reports

In randomized clinical trials (RCT), an essential part of the benefit-risk assessment of treatments is the quantification of the risk of experiencing adverse events (AEs), and comparing these risk between treatment arms. Methods commonly employed to quantify absolute adverse event (AE) risk either do not account for varying follow-up times, censoring, or for competing events (CEs), although appreciation of these are important in risk quantification, see, e.g., O’Neill [ 1 ] and Procter and Schumacher [ 2 ].

Analyses of AE data in clinical trials can be improved through the use of survival techniques that account for varying follow-up times, censoring, and CEs. Varying follow-up times refer to the fact that if patients are assessed for AEs in regular intervals it may happen, even in absence of censoring, that depending on when a patient entered the trial, the follow-up time at a reporting event varies between patients. Similar to an efficacy endpoint, censoring , or rather administrative censoring , refers to the fact that for some of the patients we may only have incomplete observations in the sense that we know that they did not experience an AE up to the cutoff of the reporting timepoint, but that their observation time to have an AE continues beyond that. A thorough discussion of CEs in the context of AE risk quantification is provided below.

Precise definitions of estimators are also given below.

The AJE [ 3 , 4 ] can be considered the non-parametric gold-standard method when quantifying absolute AE risk. The reason is that the AJE is the standard (non-parametric) estimator that accounts for CEs, censoring, and varying follow-up times simultaneously and, being non-parametric, does not rely on restrictive parametric assumptions, such as constant hazards. Any other estimator of AE probability, such as incidence proportion, probability transform incidence density, or one minus Kaplan-Meier, delivers biased estimates in general.

To quantify that bias for all these methods in an ideal scenario, Stegherr et al. [ 5 ] ran a comprehensive simulation study. Two key findings were (1) that ignoring CEs is more of a problem than falsely assuming constant hazards by the use of the incidence density and (2) that the choice of the AE probability estimator is crucial for the estimation of relative effects, i.e., comparison between groups.

To illustrate and further solidify these simulation-based results with real data the SAVVY consortium, a collaboration between nine pharmaceutical companies and three academic institutions meta-analyzed data from 17 randomized controlled trials (RCT).

In this article, we summarize the results of the empirical study, reported in two separate publications: Stegherr et al. [ 6 ] was concerned with estimation of AE risk in one treatment group and Rufibach et al. [ 7 ] with the comparison of AE risks between two groups in an RCT. A cursory assessment of how relevant guidelines recommend to estimate AE risk is given with a call for updates. We conclude with a discussion.

Definition of key terms

The target of estimation, or estimand, for the compared estimators is the probability \(P(\mathrm {AE\ in}\ [0,t])\) . We will also call this quantity risk . In situations not additionally complicated by varying follow-up times or censoring, i.e., when all patients are observed for the same amount of time, this probability can easily be estimated using the incidence proportion, see below. However, as soon as we have varying follow-up and/or censoring, the incidence proportion will typically be a biased estimate of \(P(\mathrm {AE\ in}\ [0,t])\) .

Scientific questions of the SAVVY project

The overarching scientific questions of SAVVY can be phrased as follows:

For estimation of the probability of an AE, how biased are commonly used estimators, especially the incidence proportion and one minus Kaplan-Meier, in presence of censoring, varying follow-up between patients, CEs, and in the case of incidence densities a restrictive parametric model?

What is the bias of common estimators that quantify the relative risk of experiencing an AE between two treatment arms in a RCT?

Can trial characteristics be identified that help explain the bias in estimators?

How does the use of potentially biased estimators impact qualification of AE probabilities and relative effects in regulatory settings?

Within the SAVVY project, these questions were approached in two ways: first, in Stegherr et al. [ 5 ], via simulation of clinical trial data. This approach has the advantage that the true underlying data generating mechanism is specified by the researcher and therefore known. This allows to exactly quantify the bias of a given estimator, i.e., to answer 1) and 2) above (it would also allow to answer Question 4, but that was not addressed in Stegherr et al. [ 5 ]). Second, in Stegherr et al. [ 6 ] and Rufibach et al. [ 7 ], biases of commonly used estimators of absolute and relative AE risks were estimated by comparing them to the best available estimator. Having real clinical trial data available also allows to answer Question 3 above, through meta-analytic methods.

Competing events and their connection to the ICH E9 estimands addendum

In what follows, we will use competing event (apart from direct quotes) and consider it synonymous to competing risk .

An important but largely unrecognized aspect when quantifying AE risk is the likely presence of CEs. Gooley et al. [ 8 ] define a CE as

“We shall define a competing risk as an event whose occurrence either precludes the occurrence of another event under examination or fundamentally alters the probability of occurrence of this other event”.

whereas the ICH E9(R1) estimands addendum [ 9 ] defines an intercurrent event as

“Events occurring after treatment initiation that affect either the interpretation or the existence of the measurements associated with the clinical question of interest”.

Here, another event under examination and measurements associated with the clinical question of interest refer to a defined AE of interest. So, a CE in this context is any clinical event that precludes the occurrence of an AE, the most prominent example being death. The above two definitions appear to be, if not the same, then at least very related. However, the ICH E9(R1) addendum does not discuss CEs, so it is not entirely clear how to embed CEs into the addendum framework, i.e., whether and if yes which of the proposed strategies of the estimand addendum applies to the CE situation. More research and discussion is needed to align CEs (if necessary at all), and the analysis of complex time-to-event data with the addendum.

Stegherr et al. [ 6 ] and Rufibach et al. [ 7 ] took a pragmatic approach and defined events as “competing” that preclude the occurrence or recording of the AE under consideration in a time-to-first-event analysis. Specifically, one important CE is death before AE. In addition, any event that would both be viewed from a patient perspective as an event of his/her course of disease or treatment and would stop the recording of the interesting AE was viewed as a CE. Since all these CEs apart from death may be prone to some subjectivity in the empirical analysis reported in Stegherr et al. [ 6 ] and Rufibach et al. [ 7 ], a variant of the estimators with a CE of death only was also considered. Since results were in line with the broader definition of CEs as given above, we omit the results for the death only variant here.

Estimation methods

A precise mathematical definition of all estimators of the probability of an AE that were compared in SAVVY is provided in Stegherr et al. [ 10 ], a prospectively published statistical analysis plan for the SAVVY project. A short introduction in all estimators is also provided in Stegherr et al. [ 6 ]. In this overview article, we only provide very brief descriptions of the considered estimators.

- Incidence proportion

By far the most commonly used estimator, e.g., in standard safety reporting that enters benefit-risk assessment for the approval of new medicines, to estimate the risk of an adverse event (risks are estimated for one AE at a time) up to a maximal observation timepoint \(\tau\) is the incidence proportion [ 4 ]. It simply divides the number of patients with an observed AE on \([0, \tau ]\) in group A by the number of patients in group A . The incidence proportion is an estimator of the probability that an AE happens in the interval \([0, \tau ]\) , and that this AE is observed, i.e., not censored. This illustrates that the incidence proportion is not properly dealing with censored observations. However, it correctly accounts for CEs; see Allignol et al. [ 4 ] for an exemplary illustration of that feature.

- Incidence density

To account for the differing follow-up times between patients, researchers and guidelines (see Table 4 ) often advocate to use the incidence density or incidence rate , where the number of AEs in the nominator is divided by the total patient-time at risk instead of simply the number of patients. As such, the incidence density does not directly estimate the probability of an AE, but rather the AE hazard. As described in Stegherr et al. [ 10 ], this hazard estimator can easily be transformed to indeed estimate the probability of an AE. However, it only does so assuming that the AE hazard is constant, i.e., the probability-transformed incidence density is a fully parametric estimator. In addition, as such it does not correctly account for CEs, but it can be modified to do so, leading to the probability transform incidence density accounting for CEs .

One minus Kaplan-Meier

Researchers are often aware of the inability of the incidence proportion to properly deal with varying follow-up times and censoring. As a remedy, they (and many guidelines, see Table 4 ) then advocate to consider time to AE and estimate the probability of an AE by reading off the one minus Kaplan-Meier estimator at a timepoint of interest, e.g., the end of observation time \(\tau\) or at an earlier timepoint. While indeed, this estimator properly accounts for varying follow-up times and censoring the question remains how to deal with CEs. Numerous papers have been written [ 4 , 8 ] and providing technical arguments explaining why the Kaplan-Meier estimator is a biased estimator of the probability of an AE. Intuitively, one minus the Kaplan-Meier estimator estimates the distribution function of the time of interest, that is, it tends towards one as we move to the right on the time axis. However, if we add up the probability of an AE and the probability of a CE in a truly CE scenario that also must be equal to one, implying that the probability of an AE is strictly smaller than one. As a consequence, the Kaplan-Meier estimator to estimate the probability of an AE will be biased upwards.

- Aalen-Johansen estimator

Finally, there is an estimator that at the same time accounts for (random or independent) censoring, respects varying follow-up times, accounts for CEs in the right way, and is fully nonparametric and therefore free of bias introduced by any of these processes: the AJE [ 3 ]. It is therefore considered the gold standard estimator. In the empirical analysis of the 17 RCTs in the SAVVY project, it served as a benchmark against which all estimators were measured against. The term bias was therefore used for deviations of the estimators from this benchmark estimator, or gold standard. For an evaluation of the true bias, i.e., the deviation of estimators to the true underlying value, we refer to Stegherr et al. [ 5 ].

Table 1 in Stegherr et al. [ 6 ] concisely summarizes the properties of each considered estimator with respect to whether it accounts for censoring and CEs and whether it makes a parametric assumption, and we therefore reproduce it here in Table 1 for the estimators discussed here.

Quantification of bias—the SAVVY project

One of the goals of the SAVVY project is to quantify the bias of standard estimators of the probability of an AE. Based on simulations, i.e., comparing estimated to true underlying values from which the data was simulated, this has been done in Stegherr et al. [ 5 ]. Key findings in this study were that ignoring CEs is more of a problem than falsely assuming constant hazards. The one minus Kaplan-Meier estimator may overestimate the true AE probability by a factor of four at the largest observation time. Moreover, the choice of the AE probability estimator is crucial for group comparisons.