Changing Course, Transforming Education in Bangladesh on International Day of Education 2022

Ms. Beatrice Kaldun, Head of Office and UNESCO Representative congratulated the organizers and highlighted that business as usual will not work and transforming education through Global Citizenship Education and Education for Sustainable Development is the way forward to address global challenges such as digital transformation and climate change. Referring to the Futures of Education report launched by UNESCO last November, she urged everyone to participate in the futures of education discussion and action – children, youth, parents, teachers, researchers, activists, employers, cultural and religious leaders.

More than 80 participants from the government and academic institutions attended the celebration event in person and online. Mr. Golam Hasibul Alam, Secretary of MoPME and Mr. Md. Abu Bakr Siddique, Secretary, SHED, MOE were also present at the event and made their intervention on the theme of IDE.

Related items

- UNESCO Office in Dhaka

Event International Conference of the Memory of the World Programme, incorporating the 4th Global Policy Forum 28 October 2024 - 29 October 2024

Other recent news

- Projects & Operations

Bangladesh: Ensuring Education for All Bangladeshis

Join the #ProsperBangladesh movement

You have clicked on a link to a page that is not part of the beta version of the new worldbank.org. Before you leave, we’d love to get your feedback on your experience while you were here. Will you take two minutes to complete a brief survey that will help us to improve our website?

Feedback Survey

Thank you for agreeing to provide feedback on the new version of worldbank.org; your response will help us to improve our website.

Thank you for participating in this survey! Your feedback is very helpful to us as we work to improve the site functionality on worldbank.org.

School Education System in Bangladesh

- Living reference work entry

- First Online: 22 June 2020

- Cite this living reference work entry

- Manjuma Akhtar Mousumi 3 &

- Tatsuya Kusakabe 4

Part of the book series: Global Education Systems ((GES))

434 Accesses

4 Citations

Bangladesh has seen significant changes in its education system as the country has gone through several transformations in terms of its identity – from being a part of greater Bengal in Northeast India until 1947 to being referred to as East Pakistan till 1971 and to finally becoming the present-day Bangladesh through its emergence in 1971 as a sovereign nation-state separate from Pakistan. This chapter begins by discussing the history of education in the Indian subcontinent and the education system that prevailed in the parts of the subcontinent that later came to be referred to as Bangladesh. Specific focus of the chapter is on primary and secondary education as also the nonformal education and the contribution of different stakeholders in education. The chapter discusses the education structure, governance and management, curriculum and assessment, as well as issues such as access, participation, retention, and transition in general education. This chapter also looks into government policies and programs for education, the inclusion of children deprived of education, and development partners’ contribution in providing financial and technical support to ensure participation of all in education. Overall, the chapter provides an understanding of the developments in relation to the domain of education in Bangladesh.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Institutional subscriptions

ADB. (2011). Policy brief-secondary education sector development project . Dhaka: Asian Development Bank. Retrieved from https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/29402/brief-secondary-education-development-project.pdf .

Google Scholar

Ahmed, M. (2011). Education in Bangladesh- anatomy of recent progress. In M. Ahmed (Ed.), Education in Bangladesh: Overcoming hurdles to equity and quality (pp. 1–28). Dhaka: BRAC University Press.

Ahmed, M. (2013). The Post-2015 MDG and EFA agenda and the national discourse about goals and targets: A case study of Bangladesh. NORRAG Working Paper Vol. 5 , (August 2013).

Ahmed, M. (2016). The education system. In A. Riaz & M. S. Rahman (Eds.), Routledge handbook of contemporary Bangladesh (pp. 340–351). London: Routledge.

Chapter Google Scholar

Ahmed, M. (2018a). Policy-relevant education research: A study of access, quality and equity in Bangladesh. In R. Chowdhury, M. Sarkar, F. Mojumdar, & M. M. Roshid (Eds.), Engaging in educational research: Revisiting policy and practice in Bangladesh research (pp. 21–38). Singapore: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-0708-9 .

Ahmed, M. (2018b, August 27). An education system that divides the nation. The Daily Star . Retrieved from https://www.thedailystar.net/news/opinion/perspective/education-system-divides-the-nation-1624840

Ahmed, M., & Rashid, M. (2015). A scoping study of the state of skills development with emphasis on middle-level skills in Bangladesh . Dhaka: BRAC Institute of Educational Development, BRAC University and NORRAG.

Ahmed, M., Ahmed, K. S., Khan, N. I., & Islam, R. (2007). Access to education in Bangladesh: Country analytic review of primary and secondary education. In Consortium for research on educational access, transitions and equity . Dhaka: Consortium for Research on Educational Acess, Transitions & Equity (CREATE).

Ahmed, M., Haque, K. M. E., Rahaman, M. M., & Quddus, M. A. (2016). Framework for action: Education 2030 in Bangladesh . Dhaka: Campaign for Popular Education (CAMPE).

Amin, S. (2007). Schooling in Bangladesh. In A. Gupta (Ed.), Going to school in South Asia (pp. 37–52). London: Greenwood Press.

Asadullah, M. N. (2006). Educational disparity in West and East Pakistan 1947–71: Was East Pakistan discriminated against? (Discussion papers in economic and social history). London: University of Oxford. Retrieved from https://www.economics.ox.ac.uk/materials/papers/2237/63asadullah.pdf

Asadullah, M. N. (2009). Returns to private and public education in Bangladesh and Pakistan: A comparative analysis. Journal of Asian Economics, 20 (1), 77–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.asieco.2008.05.004 .

Article Google Scholar

Asadullah, M., & Choudhury, N. (2009). Holly alliances: Islamic high schools, public subsidies and female schooling in Bangladesh. Education Economics, 17 (3), 377–394. https://doi.org/10.1080/09645290903142593 .

Azim, F. (2018). An analysis of the secondary school certificate examination: The case of creative questions. In R. Chowdhury, M. Sarkar, F. Mojumdar, & M. M. Roshid (Eds.), Engaging in educational research: Revisiting policy and practice in Bangladesh (pp. 221–238). Singapore: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-0708-9 .

BANBEIS. (2016). Bangladesh education statistics 2015 . Retrieved from http://banbeis.gov.bd/data/index.php

BANBEIS. (2017). Bangladesh education statistics 2016 . Dhaka.

Bangladesh Bank. (2020). Economic Data. Retrieved 27 Apr 2020, from https://www.bb.org.bd/econdata/exchangerate.php

Banu, R., & Sussex, R. (2001). English in Bangladesh after independence: Dynamics of policy and practice. In B. Moore (Ed.), Who’s centric now? The present state of post-colonial Englishes (pp. 123–147). Melbourne: Oxford University Press.

Banu, F. A. L., Roy, G., & Shafiq, S. (2018). Analysing bottlenecks to equal participation in primary education in Bangladesh: An equity perspective. In R. Chowdhury, M. Sarkar, F. Mojumdar, & R. M. Moninoor (Eds.), Engaging in educational research: Revisiting policy and practice in Bangladesh (pp. 39–64). Singapore: Springer Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-0708-9 .

Cameron, S. J. (2016). Urban inequality, social exclusion and schooling in Dhaka, Bangladesh. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 7925 , 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2016.1259555 .

CAMPE. (2014). Bangladesh education sector: an appraisal for basic education . Dhaka: Ministry of Primary and Mass Education (MoPME), Government of Bangladesh. Retrieved from https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=16&ved=2ahUKEwjq7sXQiqTeAhXJV30KHQGiA8UQFjAPegQIAhAC&url=https%3A%2F%2Fwww.globalpartnership.org%2Fdownload%2Ffile%2Ffid%2F46734%2520&usg=AOvVaw2g0iMfbjf1MXvKMs8RwDIK

CAMPE. (2015). Whither grade V examination: an assessment of primary completion examination in Bangladesh . (Eds: S. R. Nath, A. M. R. Chowdhury, M. Ahmed, & R. K. Choudhury). Dhaka: Campaign for Popular Education (CAMPE).

Chowdhury, R., & Kabir, A. (2014). Language wars: English education policy and practice in Bangladesh. Multilingual Education, 4 (1), 21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13616-014-0021-2 .

Chowdhury, R., & Sarkar, M. (2018). Education in Bangladesh: Changing contexts and emerging realities. In R. Chowdhury, M. Sarkar, F. Mojumdar, & M. M. Roshid (Eds.), Engaging in educational research: Revisiting policy and practice in Bangladesh research (pp. 1–18). Singapore: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-0708-9 .

Deabnath, S. (2007, October 3). Most schools dodge registration, VAT. The Daily Star . Retrieved from http://www.thedailystar.net/news-detail-6415

Directorate of Primary Education. (2015). Third Primary Education Development Program (PEDP 3)-revised . Dhaka: Ministry of Primary and Mass Education (MoPME), Government of Bangladesh. Retrieved from http://dpe.portal.gov.bd/sites/default/files/files/dpe.portal.gov.bd/page/093c72ab_a76a_4b67_bb19_df382677bebe/PEDP-3Brief(Revised).pdf

Directorate of Primary Education. (2017). Annual primary education census . Dhaka. Retrieved from http://www.dpe.gov.bd/site/publications/50b03c39-bde0-4c2f-a143-e13914cc8b7e/APSC-2017

Global Education Monitoring Report-2017/18. (2017). Accountability in education: Meeting our commitments . Paris: UNESCO. Retrieved from http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0025/002593/259338e.pdf .

GPE. (2017). GPE’s Engagement on Domestic Financing for Education . Washington, DC: Global Partnership for Education. Retrieved from https://www.globalpartnership.org/content/policy-brief-gpes-engagement-domestic-financing-education

Habib, A., & Hossain, S. (2018). Students’ sense of belonging in urban junior secondary schools in Bangladesh: Grades, academic achievement and school satisfaction. In R. Chowdhury, M. Sarkar, F. Mojumdar, & M. M. Roshid (Eds.), Engaging in educational research: Revisiting policy and practice in Bangladesh (pp. 89–102). Singapore: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-0708-9 .

Habib, W. Bin, & Sarkar, A. (2014, July 23). New guidelines to limit fees. The Daily Star . Retrieved from http://www.thedailystar.net/new-guidelines-to-limit-fees-34497

Haydon, J., & Pinon, R. (2010). The benefits of the English language for individuals and societies: Quantitative indicators from Cameroon, Nigeria, Rwanda, Bangladesh and Pakistan . London: Euromonitor International.

Hossain, M. Z. (2015). National curriculum 2012: Moving towards the 21st century. Bangladesh Education Journal, 14 (1), 7–23. Retrieved from https://www.bafed.net/pdf/ejune2015/1_National_Curriculum_2012_Moving_Towards_the_21_Century.pdf .

Hossain, A., & Zeitlyn, B. (2010). Poverty, equity and access to education in Bangladesh (Monograph). (CREATE Pathways to Access Research Monograph No. 51). Falmer: Consortium for Research on Educational Access, Transitions & Equity (CREATE).

Imam, S. R. (2005). English as a global language and the question of nation-building education in Bangladesh. Comparative Education, 41 (4), 471–486. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050060500317588 .

Kitamura, Y. (2000). Vernacular political and student elites during the East Pakistan era. Comparative Education, 2000 (26), 207–225. https://doi.org/10.5998/jces.2000.207 .

Lewin, K. M. (2007). Improving access, equity and transitions in education: creating a research agenda . London: Consortium for Research on Educational Access, Transitions & Equity (CREATE). Retrieved from http://srodev.sussex.ac.uk/1828/1/PTA1.pdf

Malak, M. S., & Tasnuba, T. (2018). Secondary school teachers’ views on inclusion of students with special educational needs in regular classrooms. In R. Chowdhury, M. Sarkar, F. Mojumdar, & M. M. Roshid (Eds.), Engaging in educational research: Revisiting policy and practice in Bangladesh research (pp. 119–139). Singapore: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-0708-9 .

Malak, M. S., Begum, H. A., Habib, A., Banu, M. S., & Roshid, M. M. (2014). Inclusive education in Bangladesh: Are the guiding principles aligned with successful practices? In H. Zhang, P. W. K. Chan, & C. Boyle (Eds.), Equality in education: Fairness and inclusion . Rotterdam: Sense.

Ministry of Education. (2007). Education structure of Bangladesh. Retrieved 27 Apr 2020, from http://old.moedu.gov.bd/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=339&Itemid=354

Monzoor, S., & Kabir, D. M. H. (2008). Primary education in Bangladesh: Streams, disparities and pathways for unified system . Dhaka. Retrieved from http://www.unnayan.org/documents/Education/Primary.Education.English.pdf .

MoPME. (2015). Education for All 2015 national review report: Bangladesh . Dhaka: Ministry of Primary and Mass Education (MoPME), Government of Bangladesh. Retrieved from http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0023/002305/230507E.pdf .

Mousumi, M. A., & Kusakabe, T. (2017). The dynamics of supply and demand chain of English-medium schools in Bangladesh. Globalisation, Societies and Education, 15 (5), 679–693. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767724.2016.1223537 .

Nath, S. R. (2002). The transition from non-formal to formal education: The case of BRAC, Bangladesh. International Review of Education, 48 (6), 517–524.

Nath, S. R. (2016). Policies, achievements and challenges in education. In S. R. Nath (Ed.), Realising potential: Bangladesh’s experiences in education (pp. 1–102). Dhaka: Academic Press and Publishers Library.

National Skills Development Policy-2011. (2014). Dhaka: National Skills Development Council, Government of Bangladesh. Retrieved from http://www.nsdc.gov.bd/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/bangladesh-gejet-2.pdf

Rahman, M., Khan, T. I., & Sabbih, M. A. (2016). Education budget in Bangladesh: an analysis of trends, gaps and priorities . Dhaka: Campaign for Popular Education (CAMPE). Retrieved from https://www.campebd.org/page/Generic/0/30/43

Rao, N., & Hossain, M. I. (2011). Confronting poverty and educational inequalities: Madrasas as a strategy for contesting dominant literacy in rural Bangladesh. International Journal of Educational Development, 31 (6), 623–633. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2011.01.012 .

Sabur, Z. U. (2007). Bangladesh non-formal education: UNESCO country overview of the provision of basic non-formal education for youth and adults . Dhaka. Retrieved from http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0015/001555/155577e.pdf

Sabur, Z. U., & Ahmed, M. (2011). Diversity in primary education provisions: Serving access with quality and equity. In M. Ahmed (Ed.), Education in Bangladesh: Overcoming hurdles to equity and quality (pp. 157–191). Dhaka: BRAC University Press.

Sharma, R. (2000). Decentralisation, professionalism and the school system in India. Economic & Political Weekly, 35 (42), 3765–3774. Retrieved from https://www.jstor.org/stable/4409866?read-now=1&refreqid=excelsior%3Acd5deee271199d12643214052abb3f6d&seq=2#page_scan_tab_contents .

Sperandio, J. (2007). Women leading and owning schools in Bangladesh: Opportunities in public, informal, and private education. Journal of Women in Educational Leadership, 5 (1), 7–20. Retrieved from https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1067&context=jwel .

Thornton, H. (2006). Teachers talking: The role of collaboration in secondary schools in Bangladesh. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 36 (2), 181–196. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057920600741180 .

UIS. (2018). Education and literacy. Retrieved 18 Apr 2020, from http://uis.unesco.org/en/country/bd

UNESCO. (2015). Bangladesh: Pre-primary education and the school improvement plan . Bangkok: UNESCO. Retrieved from http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0023/002330/233004E.pdf

UNESCO Institute for Statistics. (2017). Outbound: internationally mobile students by host region. Retrieved 1 Oct 2018, from http://data.uis.unesco.org/index.aspx?queryid=172

World Bank. (2016). Bangladesh: Ensuring education for all Bangladeshis. Retrieved 16 Oct 2018, from http://www.worldbank.org/en/results/2016/10/07/ensuring-education-for-all-bangladeshis

World Bank. (2018). World development report 2018: Learning to realize education’s promise . Washington, DC: World Bank.

Book Google Scholar

World Bank. (2020). The World Bank in Bangladesh. Retrieved 18 Apr 2020, from https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/bangladesh/overview

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

BRAC Institute of Educational Development (BRAC IED), BRAC University, Dhaka, Bangladesh

Manjuma Akhtar Mousumi

Center for the Study of International Cooperation in Education (CICE), Hiroshima University, Hiroshima, Japan

Tatsuya Kusakabe

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Manjuma Akhtar Mousumi .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India

Padma M. Sarangapani

Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Hyderabad, India

Rekha Pappu

Section Editor information

No affiliation provided

Archana Mehendale

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Mousumi, M.A., Kusakabe, T. (2020). School Education System in Bangladesh. In: Sarangapani, P., Pappu, R. (eds) Handbook of Education Systems in South Asia. Global Education Systems. Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-3309-5_11-1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-3309-5_11-1

Received : 11 May 2020

Accepted : 16 May 2020

Published : 22 June 2020

Publisher Name : Springer, Singapore

Print ISBN : 978-981-13-3309-5

Online ISBN : 978-981-13-3309-5

eBook Packages : Springer Reference Education Reference Module Humanities and Social Sciences Reference Module Education

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Essay Issue 1 — October 2023

The colonial legacy of bangladesh’s education system.

By S. B. Shams

October 6, 2023

Not to be trapped with historicism, but the discussion on the reform in the education sector in Bangladesh can only be possible with an understanding of its history. It is essential to thoroughly study the history of education before colonialism and the impact of British rule for over a century. This historical insight can be juxtaposed with an analysis of coloniality within the present-day education delivery in Bangladesh.

The Indus civilization of ancient India, from 2500-1500 BC, was skilled in many areas, including written language, arts and crafts, architecture, design, ecology, civic and administrative codes, trade and commerce, and mathematics. Education played a significant role in shaping an individual’s overall growth and development. Its purpose was not merely limited to imparting knowledge and information but extended to promoting self-confidence, self-restraint, ethics, character and personality formation, and social efficiency. Moreover, it eliminated discriminatory attitudes and fostered good judgment, which was essential for leading a successful and fulfilling life.

Ancient Indian education emphasized objective knowledge and secular needs, including conserving ancestral traditions, coding customs, and reporting on social conventions. Chantal Crozet (2012) writes and explains ancient Indian education, “Grammar and poetics, logic, astronomy, astrology, geometry, arithmetic and medicine were amongst the most valued forms of worldly knowledge.” Education in ancient times was comprehensive as it covered both physical and spiritual aspects of an individual. It included teachings on religion and spirituality to provide holistic knowledge to the learner.

The ancient Indian gurukul system required students to live with their teachers, even in remote forests or mountainous terrain. This aspect of their accommodation, where the teacher and the student were near each other, was most important for developing their relationship. The Gurukuls were one of the earliest forms of public schools supported by public donations.

At that time, knowledge was apprehended in India as something beyond the five senses since education for transformation requires education of the inner self and subjective knowledge. The Brahmanical instruction curriculum at the time, described by the Brahmin poets, involved the study of vyakaran, abhidhan, nyaya, and alankara shastra in schools.

During the Islamic era, educational institutions in India comprised traditional madrasas and maktabs. Even during British rule, the Provincial Committee of Bengal of the Indian Education Commission (1882) acknowledged that every mosque in India had an educational center. These establishments imparted knowledge on various subjects such as grammar, philosophy, mathematics, and law. The madrasas’ curriculum consisted of two books on grammar, two on logic, two on astronomy and mathematics, and five on mysticism and religious knowledge. Under the reign of the great Mughal ruler Akbar, the education system was inclusive, offering additional courses on medicine, agriculture, geography, and texts from other languages and religions, such as Patanjali’s work in Sanskrit. The scientific community during this period was influenced by the ideas of Aristotle, Bhaskaras II, Charka, and Ibn Sina.

India’s traditional education system came under scrutiny at the hands of its British rulers. In 1835, the British ruler appointed William Adam to assess indigenous institutions. Adam’s research uncovered roughly 100,000 schools in Bengal and Bihar, each operated by a single teacher known as a Guru. Students utilized the Shubhankar text for arithmetic, while Sabda Subanta and Asta Sabdi were used to teach elementary grammar. Moral values were instilled through the Sanskritic verses like Chanakya’s and many others. The surveyors of the British government found valuable knowledge being taught in indigenous schools. Nevertheless, they concluded that traditional education before British colonization lacked scientific elements in the curriculum. The colonial rulers of Bengal expressed their opinion on the education systems, stating that they were deficient in terms of “moral instruction” and “useful knowledge,” even though there was evidence to suggest otherwise.

Developing clerical classes within the Indian population to serve as administrators and supporters of imperialism was the British Raj’s covert objective in imposing English education in colonial India. Thomas Babington Macaulay, Secretary to the Board of Control 1831, who was responsible for “civilizing indigenous”, said in rhetoric, “We must at present do our best to form a class who may be interpreters between us and the millions whom we govern –a class of persons Indian in blood and color, but English in tastes, in opinions, in morals and in intellect.” He added, “To that class we may leave it to refine the vernacular dialects of the country, to enrich those dialects with terms of science borrowed from western nomenclature, and to render them by degrees fit vehicles for conveying knowledge to the great mass of the population.”

The minority ‘Orientalists’ in Britain who sought to revive India’s ancient culture through its traditional learned classes could have promoted their arguments more effectively. The ‘Anglicists’ emerged victorious by advocating for the introduction of so-called ‘modern science’ to transform what they perceived as a ‘stagnant culture’. Macaulay’s vision had produced an elite class of Anglicised Indians and a larger mass of ‘clerical workers’ with limited prospects.

The Afro-Caribbean psychiatrist and political philosopher Frantz Fanon identifies this phenomenon as a civilized form of violence or cultural injuries, like institutionalizing the ruler’s language in schools and ingraining children’s minds in a colony with the colonizer’s culture.

In Bengal, the spread of publicly run Western-style mass education was initially prompted by missionaries’ influence. There was a crucial societal shift in history during the 19th and early 20th century when the Protestants championed the cause of widespread education in their respective nations with the aim of “civilizing” the working class. This endeavor also extended to their colonies, and the so-called ‘altruistic’ notion of ‘universal education’ garnered backing from rulers, benefiting both colonized subjects overseas and the working-class populace in an empire like Britain. The British government started to fund on a limited scale to elementary education in India. In addition to providing Anglicized mass education, higher education was intended to foster a sense of national identity in the form of colonial citizenship.

In the colonial era, affluent Indians took it upon themselves to establish private schools and institutions without funding from the British government. Their unwavering commitment in providing education for their children led to the creation of institutions that closely followed the English education model, with English pedagogy and curriculum being the sole means of achieving modernization. This approach of privatized English education has persisted in post-colonial Pakistan and Bangladesh, and has yet to encounter any noteworthy opposition.

Within the Subcontinent, the disparity between government-supported formal education, which is under-resourced and adheres to colonial norms, and privately-funded modern English education for the affluent has led to significant illiteracy rates. The education system passed down to the region primarily caters to job opportunities, generating compliant citizens while encouraging post-colonial patriotism.

Rabindranath Tagore, the Bengali poet whose lyrics are the national anthems of Bangladesh and India, stated the core of the vision of Indian education. “Our link to the reality of the world is of three kinds: the connection made by the intellect, the connection arising out of need, and the connection found in joy.” (From the speech delivered by Tagore at the National Council for Education and first published in 1907). He elaborates, “This [Indian education] is not mere knowledge, as science is, but it is a perception of the soul by the soul. This does not lead us to power, as knowledge does, but it gives us joy, which is the product of the union of kindred things.”

Tagore, however, eloquently expressed the idea of what could be decolonized education delivery by criticizing the then newly imposed colonial education in his writing, “ The education we get does not match the lifestyle of ours, the urge for improvement of our home is not there in our books.” He further adds, “This [English] education can never overcome our shortcomings in life. This education is miles apart from the roots of our life.” Tagore addressed the challenges associated with conventional and colonized education by implementing innovative educational practices in his institutions at Santiniketan.

In the ancient Indian education system, knowledge had been divided into two streams: paravidya —the higher knowledge, the spiritual wisdom—and aparavidya —the lower knowledge, the secular sciences. Moreover, as Tagore mentioned, there is another stream, “the doctrine of deliverance that Buddha preached was the freedom from the thralldom of Avidyā. Avidyā is the ignorance that darkens our consciousness and tends to limit it within the boundaries of our personal self.”

In ancient Bengal, the prevailing philosophy of education aspired to connect knowledge to practical life, work, and personal fulfillment rather than purely spiritual pursuits. Tagore championed this traditional Indian educational model in his various essays, speeches, and correspondences, advocating for it over the educational approach imposed by colonial powers.

The ancient system of the scholastic tradition of meditation, Smarta (Puranic), mental mathematics, medical science-ayurvedic, sadhana including asana, pranayama, and also the education on nature was replaced, according to Dutta (2022) by a “curriculum of prescribed learning” by the colonial ruler.

Whereas both Vedic and Buddhist systems of education had different subjects of study. The Vedic system comprised ritualistic knowledge, metrics, exegetics (interpretation of scriptures), grammar, phonetics and astronomy; the Upanishads included logic and reasoning, history and more. The Subjects common to Buddhism and Vedic were law, arithmetic, performing arts, ethics, architecture, trading accounts, economics, state-craft, military science and many more. The ancient Indian education system had 64 art forms to be imparted through teaching. In brief, the ancient Indian education system catered to both spirituality and real-life skills, which were infused with the intention for salvation and final bliss or ecstasy of life enjoyed, parallel with complete physical development.

The Eastern and Western cultures have different approaches to cultivating the soul and practical life in their educational systems. The Eastern system of teaching values both theory and practical application, just like the Indian tradition. This approach is beneficial in real-life situations and can be applied in personal and professional contexts. This system develops a versatile skill set in individuals by emphasizing both aspects.

The introduction of colonial education in Bangladesh aimed to produce clerks and professional groups required for running the colonial administration and trade. Although Bangladesh gained independence from Pakistan and Pakistan gained independence earlier from British rule, the education system based on Western colonial models remains untouched.

To understand education in Bengal before colonization, writings of nationalist thinkers such as Gandhi and Vivekananda, Bose, along with Tagore, can be conferred. These sources may provide valuable insights into the ancient and indigenous educational systems of present-day Bangladesh.

In the past, the education system in Bengal was comprehensive, encompassing guru-based instruction and religious institutions. Readings of scholars like Poromesh Acharya may reveal this with evidence, verstehen , and analyses.

Bangladesh nationalized 26,000 primary schools after gaining independence from Pakistan in 1971. The government declared that education would be compulsory, secular, and modernized. Another turn happened in 1976; military rulers encouraged expanding religious education. From the ’80s, Bangladesh experienced increased funding for Madrasahs, while in the ‘90s, teachers’ unions gained more power through patronage and bargaining. At the same time, Bangladesh entered into the global (new-imperial) policy regime of Universal Primary Education in the ‘90s.

Despite controversy and paradoxical implications, the Compulsory Primary Education Act of 1990 led to the privatization and Islamization of education and the expansion of public institutions on a large scale. Since the installation of the election and bi-party government in 1990, all subsequent governments have prioritized creating access to education through incentives and infrastructure, increasing the number of teachers, and incorporating national history and identity into the curriculum, although with varying versions of national histories.

Bangladesh achieved tremendous success in creating 100 percent access for all children in primary education and earned gender parity. Bangladesh is running a show now with the world’s most expanded public education sector, considering the numbers of schools, teachers and students. However, a few Bangladeshis but expatriate researchers referred to this trend as a “holy alliance” of support for Madrasahs and expanding access to education for poor girls, significantly contributing to the system’s rapid expansion. A few researchers mentioned that non-governmental organizations’ non-formal schools also played a role in expanding access to schooling in Bangladesh. It will be a tall list of tasks that the political governments did, including building schools, deploying teachers, provisioning zero fee, free textbooks, school meals, stipends and much more.

Recently Bangladesh has been criticized for low quality of education at all levels, particularly for the poor communities. This issue is common in many least-developed and developing countries, where although more children are completing primary education, most struggle to acquire basic literacy and numeracy skills.

Bangladesh ranks 112th out of 138 countries on the Global Knowledge Index 2020 (UNDP, 2020) by the United Nations Development Program and the Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum Knowledge Foundation. Bangladesh scored below the global average in primary education, with a score of only 35.9. In pre-university education, Bangladesh ranked 117th, scoring only 43.9. In the higher education sector, Bangladesh is ranked 129th, with a score of 24.1. (UNDP 2020)

It is commendable that Bangladesh has made significant strides in promoting education among its populace. However, there remains an urgent need to improve the quality of education delivery within the country. This would undoubtedly lead to the development of a more resilient and well-informed society capable of addressing the challenges the modern world poses.

The government has put in place a uniform approach to encourage students and their families by offering complimentary textbooks, school lunches, universal allowances, and various other rewards. Furthermore, there is a notable endeavor to enhance infrastructure. Although the state aims to establish a standardized curriculum, there exist different types of educational systems, including Madrasa, English medium, and government-run schools, that coexist. Private initiatives serve the urban middle class while the wealthy can access education abroad or in ‘foreign enclaves’.

There is another type of colonialism present within national settings these days. Bijoy Barua states, “Cultural homogenisation through the establishment of a centralized and standardized curriculum in education has become the dominant model in Bangladesh today, a model of education deeply rooted in the colonial legacy of materialism, acquisitiveness, and social exclusion. The human capital approach indoctrinates learners into the urban-based economic growth model with the financial and technical assistance of bilateral and multilateral donors in the country.” When studying the cultural marginalization of Buddhists in the Bangladesh education system, Barua confronts this.

Mrinal Debnath (2020) found similar results when studying the alienation of the Santal minority group in Bangladesh from the government’s formal and standardized education system. In this rural context, these alien ideologies and practices in education are actively engaged in eliminating local institutions, the knowledge system of indigenous peoples, the texture of their lives, their joy of living, their spirituality and their sense of being.”

Sudipta Kaviraj (2014) has excellently explained this bias , “ Ironically, for some, the relation with the West is still most significant; Western certificates are still of the highest value, and therefore Western approval or disapproval is a matter of special exultation or mortification.” During the colonial era, many Bengali elites favored implementing Western education, emphasizing modern values like ‘productivity’ and ‘civility’.

Jana Tschurenev (2019), a policy analyst, argues that unquestioningly adopting colonial education is the initial step in transnational education projects such as donor-funded initiatives for universal primary education or the education objectives of MDGs and SDGs, which claim to provide universal education rights and promoting universal access. In addition, the global model of standardized higher education continues today under neoliberal economic projects and the agenda of ‘human capital’ development, promoting the global flow of skills based on the global division of labor.

Ideas on the importance of universal primary education spread globally and impacted national leaders and policies through aid initiatives and international conferences like the 1990 Jomtien Conference on Education for All (EFA). These EFAs culminated in MDG and SDGs. A global framework based on rights has been established to promote educational access, equity, and accountability through monitoring. This approach has shifted the focus away from prioritizing efficiency, relevance and rate of return at the national level. Instead, it encourages the expansion of formal schooling and private universities worldwide. The roots of these transnational projects under the neo-liberalism and rights framework can be traced back to the Western education dumped by colonial powers in their dominions, colonies, or chartered company areas.

The current education system of Bangladesh at all levels heavily emphasizes Western philosophies and adopts Eurocentric teaching methods. The predominant language used in the global education model is English, and the curriculum follows Anglo-American templates. Bangladesh is not an exception. It is essential to acknowledge that this system results from the Western-centric geopolitical power structure and originates in the history of colonialism.

The current global education model has two primary mechanisms at work. The first involves non-western countries importing programs, curricula, materials, and even human resources from the West. The second mechanism involves a flow of international students, skilled professionals, and semi-skilled workers from the East to the West. These interactions take place through advanced business agreements and also through learning from the colonial days and successes of colonizing minds and labors.

Shibao Guo & Yan Guo (2020) reiterate that “……critical scholars question internationalization as the dominant global imaginary and its colonial myth of Western ontological and epistemological supremacy.” According to Shahjahan (2011), postcolonial studies on education and development have shown that Western colonization has had an impact on education, resulting in an emphasis on individualism over collectivism, a Western-centric view of history, and a preference for Western science over indigenous knowledge.

Robin Shields (2013) notes that donor organizations tend to place blame on schools for the lack of quality education and then shift their attention (on tension) from central to local levels. This perpetuates a pattern of colonial domination that originates from the global epicenter and trickles down to the local level, creating a power dynamic that can harm the education system. Addressing these underlying issues is crucial to establishing a more equitable and effective education system that benefits all students, regardless of their background or location.

Linda Tuhiwai Smith, a prominent Maori scholar, has coined the term “Imperial Eyes” to describe the institutionalized practices of the education system. This term refers to the manner in which colonial powers have historically imposed their cultural values and beliefs onto indigenous communities, often through the education system. Such practices have had a profound impact on the way these communities view themselves and the world around them and continue to shape their experiences today (Kellner & Gennaro, 2022).

The policy environment of Bangladesh needs to acknowledge this method of plurality; instead, both the donors and government pursue the singular global model of neo-liberal and positivist stance. This can also be termed ‘embedded policy coherence’ between donors and the government, which is the denial of declonization agenda and accommodating vernacular but diversified pedagogy and curriculum. It can be considered as a managed convergence between donors and government. Bangladesh’s education policies have been influenced by centuries of colonialism and currently align with (so-called) rights-based, (national) economy-determined, and (international) market-oriented technical reductionism.

Renowned scholars, including Foucault, Gayatri, and Fanon, argue that addressing “decolonization as epistemological reconstitution” is crucial before attempting to decolonize any education system. Adhering to a decolonial viewpoint can foster an approach to educational policy that embodies love, striving towards promoting social justice and inclusive practices. In contrast, the unfortunate gift of colonial education is the ‘exclusionary nature of knowledge and ways of knowing’ and the absence of ‘contexts’ (Leonardo & Singh, 2017).

Scholars such as Connell and Dei champion counterhegemonic methods that aim to undermine the Eurocentric knowledge that dominates our society. These alternative approaches have the power to upend the existing structures of knowledge production and foster meaningful change by celebrating the unique and valuable perspectives of historically overlooked and marginalized communities.

Moreover, through an examination of the ideas put forth by Fanon, we can gain a deeper understanding of how the systematic exclusion of certain groups based on factors like gender, religion, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status from access to quality education perpetuates the same kind of colonial violence that has suppressed them throughout history.

To conduct a comprehensive evaluation of educational policies, it is imperative to factor in the influence of colonialism on knowledge generation. Educational and policy-making processes can perpetuate power disparities between colonizing and colonized parties. Therefore, a conceptual framework that recognizes such dynamics is essential for dismantling colonial structures in education policy analysis.

When considering the concept of decolonizing education, it is imperative to recognize that there often needs to be a better interpretation of its meaning. While some individuals may believe that simply incorporating more diverse materials into the curriculum is sufficient, Khoo et al. (2020) argue that this approach only scratches the surface. The true significance lies in critically assessing the methods of obtaining knowledge and skills. This necessitates exploring alternate sources of information and pathways to knowledge that may have been disregarded due to existing power structures and spatial limitations.

Critical reflection is essential in cultivating a comprehensive understanding of the world around us. Decoloniality involves contesting, deconstructing, and triumphing over knowledge systems perpetuating global inequalities and injustices. Education has shifted its focus from cultivating critical thinking to prioritizing “cognitive” skills for job training. This inconsistency in policy objectives regarding the purpose of education becomes more ‘coherent’ in its implementation when Western donors and investors collaborate with local policy elites. Bangladesh is no exception.

To achieve the critical goal of decolonizing education, restructuring the education system is paramount. This includes changes to the hierarchy, learning objectives, and teaching methods.. Teachers should have more control over their evaluations. A practical solution requires reviving traditional knowledge and practices that were previously ignored and undervalued. Although some of this knowledge may have been deemed unimportant, it is still relevant and necessary. However, the current power structures often suppress this knowledge, making it challenging to include it in a comprehensive reform plan. Nonetheless, including this overlooked knowledge is essential to creating a more inclusive and effective solution.

Successful decolonization efforts can be observed in countries such as Vietnam, Malaysia, and Latin American nations. Some states have integrated local pedagogies, such as traditional practices related to health, well-being, or artisan training, to challenge colonial epistemology. However, these initiatives often encounter power dynamics, are less visible, and are dismissed as weak or ‘mystical’. They are frequently viewed as representing only a lower level of traditional skills, necessitating active efforts to transform these policy perceptions. Despite these challenges, Bangladesh has little alternative but to move away from its colonial roots in order to reinvigorate its education system.

About the Author

S. b. shams is a sociologist who has made several unsuccessful attempts at entrepreneurship and policy advocacy. he is a keen observer but writes infrequently., featured posts.

Roots and Routes

By Jannat Ferdous

Sportsman and Scholar: the Story of an Unlikely Friendship

By Ramachandra Guha

Music at Home: A Portrait of Provincial Life

By Mursalin Mosaddeque

Towards Utopia

By Sarah Islam

Flesh and Bone

By Ayaan Halder

Education Reform in Bangladesh and Disenfranchised Policy Analysis

Shonar Tori: On Questions—the Agrarian, the Literal, and the Literary

By Aninda Rahman

Growing Up in Red China — My Peking Days

By Razia Sultana Khan

All Flesh is Grass

By Sayani Sarkar

The Colonial Legacy of Bangladesh's Education System

Narsingdi/ Noshundi

By Sarker Hasan Al Zayed

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

State of primary education in Bangladesh: Progress made, challenges remained

Related Papers

Abstract: The positive relationship between education and development is well-established. There is common agreement among researchers, policy makers, donors and development practitioners that education is the most important tool for development and poverty reduction. Since the 1990s, a greater emphasise has been placed on Education For All (EFA) and significant amounts of resources have been invested by national governments, various Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs), and international donor agencies to realise the goals and objectives of the EFA. By using data from ten primary (five governments and five non-governments) schools from Gazipur district in Bangladesh, this paper shows a substantial progress since the1990s in terms of both enrolment and gender equity in primary education. The paper, however, argues that the quality of the education is being deteriorated since the implementation of the EFA. The paper, therefore, argues that unless the quality of the education is ensu...

International Journal of Research in Business and Social Science (2147- 4478)

This study investigates the impact of a number of educational institutions and students per teacher on the literacy rate. Data of 489 Upazilasrelating to the dependent (literacy rate) and independent variables (no. of educational institutions and students per teacher of different types of primary and equivalent educational institutions) of 8 Divisions were collected from District Statistics 2011 of Bangladesh Bureau of Statistics. The Ordinary Least Square (OLS) method is used in this study. This research found that a number of government primary schools had a significant positive relationship with the literacy rate in Barishal, Chittagong, Khulna, and Mymensingh Divisions.

BIGD, BRAC University

CenRaPS Journal of Social Sciences

Dr. Gazi Ibrahim Al Mamun

Bangladesh is committed to ensuring quality education for all. In this purpose, there is categories study/education system at the primary level of education. One is formal primary education school run by the Bangladesh government and another is non-formal primary education school run by NGOs. Both types of primary education’s main objective are ensuring quality education at primary level. But there are many problems in these two categories of an education program. But quality education’s main characteristics enable all learners to develop the capabilities they require to become economically productive, develop sustainable livelihood, contribute to peaceful and democratic societies and enhance wellbeing. The learning outcomes that are required vary at the end of the basic educations cycle must include threshold levels of literacy and numeracy and life skills including awareness and prevention of disease. In this circumstance, the learning method will be flexible and the environment o...

Shuchita Sharmin

Education is a development agenda. Due to lack of reliable data the information is approximate, it is reported in different literature that there are 16.5 million primary-school-aged children (6 to 10 years old) in Bangladesh or overall there are more than 17 million students at the primary level; again it is estimated that 15.09 million children between the ages of 6 and 10 attend primary school. It can be said that somewhat 16-17 million children between the ages of 6 and 10 attend primary school. Education is their right but achieving their right to education is a huge challenge. Bangladesh's commitment to education has been clearly stated in its Constitution and development plans with education being given the highest priority in the public sector investments. Education sector allocations are currently about 2.3 percent of GDP and 14 percent of total government expenditure. Maintaining this commitment to the education sector is imperative in order to achieve Education for Al...

see the full paer

res publication

accounts ziraf

BRAC has been a pioneer in the education arena. It has been working in the domain of primary education for almost two decades. BRAC has improved access and quality education for a significant number of children in Bangladesh. This paper focuses on enrollment, status, attendance, completion and dropout position of the child (students) of BRAC Primary School. This study was based on two sets of interview schedule designed in the light of the objectives of the study. The study reveals that the students of BRAC School (grade-iii students) are in the age 9 to 12 years. Though most of the students of BRAC primary school come from lower middle class or poor family, their enrollment and completion rates are very good. Their dropout rate is very low but attendance rate is very high. Their learning status is also good. In this study, it was found that boys and girls enrollment rates are 37.18% and 62.82% in BRAC primary school respectively. Teacher's education level is not high-quality. Their salary is also poor. This paper draws some recommendations like Scholarship program; awareness program, more evaluation and monitoring program etc. need to be taken for BRAC Primary School.

RSIS International

The primary education system in Bangladesh is one of the largest systems in the world. The country has taken a number of measures to improve primary education since its independence 1971. Bangladesh is committed to the rights of basic education for all children by the Article 17th of its constitution. Now a days Bangladesh has improved a lot in case of primary level enrolment, but many children are dropped out for various reason. To complete the full cycle of primary education (up to grade five), dropout should be reduced to zero level. Bangladesh Government also trying best to reach that goal by introducing many project such as Hard to Reach, Reaching Out of School Children ( ROSC) and also creating new division in Directorate of Primary education like Second Chance and Alternative Education (SCE) Division. All these efforts are giving good results but yet to go a long way.

Wasima Chowdhury

Zohara Ummey Hassan

RELATED PAPERS

Pablo Gatti

Moses Karakouzian

Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications

Donita Africander

Revista Estudios Socio Juridicos

PAULA LISBETH SANIPATIN RUIZ

S. Thangboi Zou

Revista Española de Medicina Nuclear

Martín Ordóñez

International Journal of Molecular Sciences

Philipp Stiegler

Soil Science

José Miguel Reichert

Clinical Cancer Research

Ramesh Boinpally

IRJET Journal

The Journal of Wildlife Management

John Litvaitis

International Journal of Academic Research in Business and Social Sciences

NORAMIRA FATEHAH AZMAN

Notulae botanicae Horti Agrobotanici Cluj-Napoca

Sara González Orenga

Revista de Enfermería Neurológica

Sandra Hernández Corral

Rosario Ramos

Revista de Educación a Distancia (RED)

Carla Patrão

Physical Review Applied

Michael Caouette-Mansour

Sylvia Nogueira

Contemporary Sociology

Joel Devine

Journal of Molecular Graphics and Modelling

Ajeet Singh

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

- High contrast

- Representative

- Meena and UNICEF

- National Ambassadors

- MEDIA CENTRE

Search UNICEF

The future of 37 million children in bangladesh is at risk with their education severely affected by the covid-19 pandemic.

- Available in:

DHAKA, 19 October 2021 — The education of 37 million children in Bangladesh and about 800 million children in Asia, including South Asia, Southeast Asia and East Asia, has been disrupted due to school closures since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic in early 2020, according to the report, ‘Situation Analysis on the Effects and Responses to COVID-19 on the Education Sector in Asia’ (SitAn Report), released today by UNICEF and UNESCO.

The Report highlights the continued impact of the pandemic on children’s education and features various regional government’s programmes and initiatives to respond to it. At a time of the year when children traditionally should have returned to school from annual holidays, the report urges governments to reopen schools as soon as it is safe to do so.

In some countries, for example the Philippines, schools have been closed throughout the entire pandemic to date, leaving an estimated 27 million students in pre-primary to secondary education without any in-person learning, a continuous period running from early 2020 to the present for over a year and counting. In Bangladesh, schools were closed throughout the entire pandemic until 12 September, when they reopened again.

Even now, as the world enters the last quarter of 2021, many children are facing an unprecedented second year of school closures as new variants of the coronavirus spread across the region. The associated consequences of such continuous school closures are staggering and include learning loss; mental distress; missed school meals and routine vaccinations; heightened risk of drop out of structured education; increased, child labour; and increased child marriage. Many of these dire consequences are already affecting countless children, and many will continue to be felt in the years to come.

“We cannot overlook the impact that the disruption of education services has had on children, particularly the most vulnerable. When schools remain closed, children miss out on the biggest opportunity to learn and develop to their full potential. The future of an entire generation is at stake; therefore, we need every effort to ensure a safe reopening of schools as soon as possible. Otherwise, the learning loss will be difficult to overcome,” stated Marcoluigi Corsi, UNICEF Regional Director a.i. for East Asia and Pacific.

While countries across Asia are taking actions to provide students with distance learning, a UNICEF-supported study by the Campaign for Popular Education (CAMPE) showed that two out of three pre-primary to upper secondary students in Bangladesh, were not reached through remote education during pandemic school closures. In addition to the lack of material assets and support to access technology, other significant obstacles that prevent disadvantaged children, and many girls, from accessing distance learning during these difficult times include a generally poor learning environment, an increase in pressure to take up domestic household chores and being forced to work outside the home.

This is why the report underscores the importance of delivering equitable and inclusive distance learning at scale to reach all children during full or partial school closures, while providing a package of support to ensure children’s health, nutrition and wellbeing. It also calls on governments and partners to strengthen teaching and teacher support, so as to address current low levels of learning and help narrow the learning divide, and protect and preserve education funding.

“With schools now open in Bangladesh after an 18-month closure, we must spare no effort to rapidly put in place mechanisms that help children catch-up, keeping a particular focus on the most disadvantaged children. Now is the time to invest, to strengthen the education system, and to bridge digital inequalities,” said Mr. Sheldon Yett, UNICEF Representative to Bangladesh.

Unless mitigation measures are swiftly implemented, the Asian Development Bank (ADB) estimates an economic loss of USD $1.25 trillion for Asia, which is equivalent to 5.4 per cent of the region’s 2020 gross domestic product (GDP). Existing evidence shows that the cost of addressing learning gaps are lower and more effective when they are tackled early on in a crisis, and that ongoing investments made in education will support economic recovery, growth and prosperity.

“Governments, partners and the private sector will need to work together, not only to get the strategies and levels of investment right, but to build more resilient, effective and inclusive systems that are able to deliver on the promise of education as a fundamental human right for all children, whether schools are open or closed,” said George Laryea-Adjei, UNICEF Regional Director for South Asia.

The increased risk of dropping out of schools due to the pandemic, especially for girls and children in poor and already marginalized families, threatens to reverse progress made in school enrolment in recent decades. According to the Report, education budgets in the region will need to increase by an average of 10 per cent to catch up with such losses if Asia is to reach the education targets of the UN 2030 Agenda’s Sustainable Development Goals in the next nine years.

“While major efforts are needed to mitigate the learning loss of those children who return to school in the post-COVID-19 recovery phase, we must also remember that 128 million children in Asia were already out of school at the onset of the pandemic; this figure represents roughly half of all out-of-school children globally. This is a learning crisis which needs to be addressed,” said Shigeru Aoyagi, Director of UNESCO Bangkok.

Since the start of the pandemic, UNICEF and UNESCO have supported national governments to maintain and improve interventions to ensure continuity of children’s learning and to safely reopen and operate schools.

UNICEF and UNESCO would like to acknowledge the generous financial contribution of the Global Partnership for Education (GPE), without which this SitAn would not have been possible.

Download high-res version here .

Download more multimedia content here .

Notes to editors:

Main publication landing page .

In addition to the comprehensive regional overview of the education situation in Asia, the Situation Analysis features case studies from fourteen countries, which provide a more detailed analysis and focus on specific thematic areas. Sub–regional reports are also available for East Asia, South Asia , and South East Asia. The findings and recommendations are informed by a comprehensive desk review of the available evidence and in-detail interviews with policy makers, teachers and community members in countries across the region.

The findings and recommendations for Bangladesh can be found here .

Together with the SitAn Report, UNICEF is also releasing a video that highlights the impact of the pandemic on education and proposes a vision for a better education future for all children in the region.

Media contacts

About unicef.

UNICEF promotes the rights and wellbeing of every child, in everything we do. Together with our partners, we work in 190 countries and territories to translate that commitment into practical action, focusing special effort on reaching the most vulnerable and excluded children, to the benefit of all children, everywhere.

For more information about UNICEF and its work for children, visit www.unicef.org/bangladesh

Follow UNICEF on Facebook and Twitter

About UNESCO

Education is UNESCO’s top priority because it is a basic human right and the foundation for peace and sustainable development. UNESCO is the United Nations’ specialized agency for the worldwide development of education, science, and culture initiatives and for providing global and regional leadership to drive progress, to strengthen the resilience and capacity-building of national systems to serve all learners, and to respond to contemporary global challenges through transformative learning pedagogies.

For more information about UNESCO and its work, visit: www.unesco.org

Follow UNESCO on Twitter , Facebook , Instagram and YouTube

About Learning and Education2030+ (LE2030+) Networking Group

The Learning and Education2030+ Networking Group which is co-chaired by UNESCO and UNICEF, is actively leading the SDG 4 efforts and initiatives in this region and regularly contributes to global discussions both at High Level Political Forum and Global Steering Committee meetings.

For more information about LE2030+ and its work, visit: apa.sdg4education2030.org

Follow Learning and Education2030+ on Facebook

Related topics

More to explore, children are at high risk amid countrywide heatwave in bangladesh, from child labour to education.

Rohingya refugee children find education and protection at UNICEF-supported multi-purpose centres¬

A year of hope and empowerment for children in Dhaka South

AACT and UNICEF helps ensure to bring back out-of-school children

UNICEF: Against the odds, children begin the new school year in Rohingya refugee camps

- Laws & Rights

- Stock Market

- Real Estate

- Middle East

- North America

- Formula One

- Other Sports

- Science, Technology & Environment

- Around the Web

- Webiners and Interviwes

- Google News

- Today's Paper

- Webinars and Interviews

How is the new education curriculum impacting teachers and parents?

- Emphasis on real-world skills with no exams up to third grade

- Assessments include acting, debates, storytelling and collaborative projects

- Parent perspectives vary on efficacy of traditional testing methods

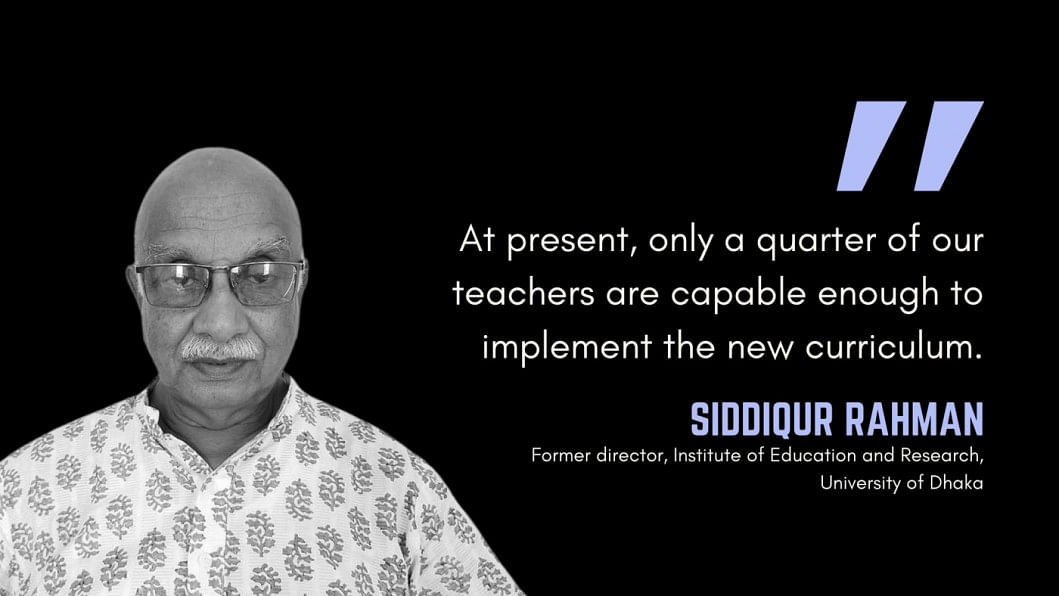

The new curriculum that has been introduced in Bangladesh heralds a departure from traditional examination-centric learning. The unveiling of this curriculum, implemented in stages starting in 2023, has sparked widespread interest and speculation about its impact on the educational landscape.

Designed with a strong emphasis on practical education, the new textbooks aim to equip students with real-world skills. A notable departure from convention is the absence of examinations up to class 3. However, as students progress to higher grades, assessments will be conducted through a multifaceted approach encompassing activities such as acting, debates, storytelling, presentations, and collaborative projects alongside traditional examinations.

Discussing the intricacies of the new curriculum, Hasina Momtaz, a Bengali subject teacher at Viqarunnisa Noon School and College, highlighted key changes. She emphasized the elimination of conventional question patterns and the deferment of examinations until after class 3, with a shift towards continuous evaluation during the learning process.

Under the revamped system, primary education comprises eight books, while secondary levels are supported by 10 textbooks. The commencement of public examinations is deferred until students reach the Secondary School Certificate (SSC) level, where subjects will not be divided into science, arts, or commerce streams.

Addressing concerns surrounding assessment methods, Momtaz clarified that students' progress is gauged through a combination of class work, presentations, projects, and group activities. The delineation of subjects begins in class 11, with a cohesive approach maintained until class 10.

Feedback on the new curriculum has been largely positive, with Momtaz noting increased student engagement and confidence. She revealed plans to expand the curriculum to include 4th and 5th classes in the upcoming academic year, following its successful implementation in 2nd, 3rd, 8th, and 9th grades.

Teachers have undergone comprehensive training spanning seven days to familiarize themselves with the new curriculum. Additionally, they have been equipped with a smart mobile application, "New Naipunya," tailored for efficient data management and reporting on student assessments.

Looking ahead, Momtaz expressed optimism about the curriculum's potential to enhance students' preparedness for higher education.

While discussions loom regarding its integration into university entrance examinations, the response from parents has been varied, reflecting a spectrum of perspectives on the efficacy of traditional testing methods versus the innovative approach embraced by the new curriculum.

A parent, who preferred not to be named, commented: “My daughter entered eighth grade this year. There are no more exams; instead, they are exposed to different activities through various routines. I don't understand what they will do without exams, since there is no pressure on the students or my daughter to study.”

Another parent (who did not want to be named) said: “There is no examination now. This is a very new curriculum for the students. We hope it will be helpful for the students to grow, and there will be good results.”

Expert: Collaborative efforts can elevate nursing education in Bangladesh

Educating rohingya children: initiatives to maintain cultural roots tied to myanmar, government extends free primary schooling up to grade eight, farewell program for 34th, 35th batch of civil engineering department students held at uits, two ministries to collaborate to ensure free education up to eighth grade, saber: environmental conservation topics are being included in textbooks, lgrd minister: eid-ul-adha waste to be cleared within 24 hours, mcci: bangladesh’s business climate hits 3-year low plagued by power outages, financing crunch, india’s grueling, acrimonious election campaign comes to an end, dhaka seeks imo to safeguard developing countries interest, cyclone remal: over 100 animal carcass recovered in sundarbans.

Popular Links

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Advertisement

Connect With Us

- IIEP Buenos Aires

- A global institute

- Governing Board

- Expert directory

- 60th anniversary

- Monitoring and evaluation

- Latest news

- Upcoming events

- PlanED: The IIEP podcast

- Partnering with IIEP

- Career opportunities

- 11th Medium-Term Strategy

- Planning and management to improve learning

- Inclusion in education

- Using digital tools to promote transparency and accountability

- Ethics and corruption in education

- Digital technology to transform education

- Crisis-sensitive educational planning

- Rethinking national school calendars for climate-resilient learning

- Skills for the future

- Interactive map

- Foundations of education sector planning programmes

- Online specialized courses

- Customized, on-demand training

- Training in Buenos Aires

- Training in Dakar

- Preparation of strategic plans

- Sector diagnosis

- Costs and financing of education

- Tools for planning

- Crisis-sensitive education planning

- Supporting training centres

- Support for basic education quality management

- Gender at the Centre

- Teacher careers

- Geospatial data

- Cities and Education 2030

- Learning assessment data

- Governance and quality assurance

- School grants

- Early childhood education

- Flexible learning pathways in higher education

- Instructional leaders

- Planning for teachers in times of crisis and displacement

- Planning to fulfil the right to education

- Thematic resource portals

- Policy Fora

- Network of Education Policy Specialists in Latin America

- Publications

- Briefs, Papers, Tools

- Search the collection

- Visitors information

- Planipolis (Education plans and policies)

- IIEP Learning Portal

- Ethics and corruption ETICO Platform

- PEFOP (Vocational Training in Africa)

- SITEAL (Latin America)

- Policy toolbox

- Education for safety, resilience and social cohesion

- Health and Education Resource Centre

- Interactive Map

- Search deploy

IIEP Publications

Advanced search

- Library & resources

- IIEP Publishing

Rural education in Bangladesh: problems and prospects

Online version

About the publication.

Publications Homepage

Related books

Early warning systems: how to support inclusive educational pathways

Designing policies for flexible learning pathways in higher education: self-assessment guidelines for policy makers and planners

Prendre en compte le genre dans les stratégies et pratiques du ministère de l’Éducation au Burkina Faso

Políticas educativas en busca de viabilidad

- Privacy Notice

ESSAY SAUCE

FOR STUDENTS : ALL THE INGREDIENTS OF A GOOD ESSAY

Essay: Bangladesh Education

Essay details and download:.

- Subject area(s): Education essays

- Reading time: 21 minutes

- Price: Free download

- Published: 24 July 2019*

- File format: Text

- Words: 5,930 (approx)

- Number of pages: 24 (approx)

Text preview of this essay:

This page of the essay has 5,930 words. Download the full version above.