- Reserve a study room

- Library Account

- Undergraduate Students

- Graduate Students

- Faculty & Staff

How to Conduct a Literature Review (Health Sciences and Beyond)

What is a literature review, traditional (narrative) literature review, integrative literature review, systematic reviews, meta-analysis, scoping review.

- Developing a Research Question

- Selection Criteria

- Database Search

- Documenting Your Search

- Organize Key Findings

- Reference Management

Ask Us! Health Sciences Library

The health sciences library.

Call toll-free: (844) 352-7399 E-mail: Ask Us More contact information

Related Guides

- Systematic Reviews by Roy Brown Last Updated Oct 17, 2023 559 views this year

- Write a Literature Review by John Glover Last Updated Oct 16, 2023 2948 views this year

A literature review provides an overview of what's been written about a specific topic. There are many different types of literature reviews. They vary in terms of comprehensiveness, types of study included, and purpose.

The other pages in this guide will cover some basic steps to consider when conducting a traditional health sciences literature review. See below for a quick look at some of the more popular types of literature reviews.

For additional information on a variety of review methods, the following article provides an excellent overview.

Grant MJ, Booth A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Info Libr J. 2009 Jun;26(2):91-108. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x. Review. PubMed PMID: 19490148.

- Next: Developing a Research Question >>

- Last Updated: Mar 15, 2024 12:22 PM

- URL: https://guides.library.vcu.edu/health-sciences-lit-review

Health (Nursing, Medicine, Allied Health)

- Find Articles/Databases

- Reference Resources

- Evidence Summaries & Clinical Guidelines

- Drug Information

- Health Data & Statistics

- Patient/Consumer Facing Materials

- Images and Streaming Video

- Grey Literature

- Mobile Apps & "Point of Care" Tools

- Tests & Measures This link opens in a new window

- Citing Sources

- Selecting Databases

- Framing Research Questions

- Crafting a Search

- Narrowing / Filtering a Search

- Expanding a Search

- Cited Reference Searching

- Saving Searches

- Term Glossary

- Critical Appraisal Resources

- What are Literature Reviews?

- Conducting & Reporting Systematic Reviews

- Finding Systematic Reviews

- Tutorials & Tools for Literature Reviews

- Finding Full Text

What are Systematic Reviews? (3 minutes, 24 second YouTube Video)

Systematic Literature Reviews: Steps & Resources

These steps for conducting a systematic literature review are listed below .

Also see subpages for more information about:

- The different types of literature reviews, including systematic reviews and other evidence synthesis methods

- Tools & Tutorials

Literature Review & Systematic Review Steps

- Develop a Focused Question

- Scope the Literature (Initial Search)

- Refine & Expand the Search

- Limit the Results

- Download Citations

- Abstract & Analyze

- Create Flow Diagram

- Synthesize & Report Results

1. Develop a Focused Question

Consider the PICO Format: Population/Problem, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome

Focus on defining the Population or Problem and Intervention (don't narrow by Comparison or Outcome just yet!)

"What are the effects of the Pilates method for patients with low back pain?"

Tools & Additional Resources:

- PICO Question Help

- Stillwell, Susan B., DNP, RN, CNE; Fineout-Overholt, Ellen, PhD, RN, FNAP, FAAN; Melnyk, Bernadette Mazurek, PhD, RN, CPNP/PMHNP, FNAP, FAAN; Williamson, Kathleen M., PhD, RN Evidence-Based Practice, Step by Step: Asking the Clinical Question, AJN The American Journal of Nursing : March 2010 - Volume 110 - Issue 3 - p 58-61 doi: 10.1097/01.NAJ.0000368959.11129.79

2. Scope the Literature

A "scoping search" investigates the breadth and/or depth of the initial question or may identify a gap in the literature.

Eligible studies may be located by searching in:

- Background sources (books, point-of-care tools)

- Article databases

- Trial registries

- Grey literature

- Cited references

- Reference lists

When searching, if possible, translate terms to controlled vocabulary of the database. Use text word searching when necessary.

Use Boolean operators to connect search terms:

- Combine separate concepts with AND (resulting in a narrower search)

- Connecting synonyms with OR (resulting in an expanded search)

Search: pilates AND ("low back pain" OR backache )

Video Tutorials - Translating PICO Questions into Search Queries

- Translate Your PICO Into a Search in PubMed (YouTube, Carrie Price, 5:11)

- Translate Your PICO Into a Search in CINAHL (YouTube, Carrie Price, 4:56)

3. Refine & Expand Your Search

Expand your search strategy with synonymous search terms harvested from:

- database thesauri

- reference lists

- relevant studies

Example:

(pilates OR exercise movement techniques) AND ("low back pain" OR backache* OR sciatica OR lumbago OR spondylosis)

As you develop a final, reproducible strategy for each database, save your strategies in a:

- a personal database account (e.g., MyNCBI for PubMed)

- Log in with your NYU credentials

- Open and "Make a Copy" to create your own tracker for your literature search strategies

4. Limit Your Results

Use database filters to limit your results based on your defined inclusion/exclusion criteria. In addition to relying on the databases' categorical filters, you may also need to manually screen results.

- Limit to Article type, e.g.,: "randomized controlled trial" OR multicenter study

- Limit by publication years, age groups, language, etc.

NOTE: Many databases allow you to filter to "Full Text Only". This filter is not recommended . It excludes articles if their full text is not available in that particular database (CINAHL, PubMed, etc), but if the article is relevant, it is important that you are able to read its title and abstract, regardless of 'full text' status. The full text is likely to be accessible through another source (a different database, or Interlibrary Loan).

- Filters in PubMed

- CINAHL Advanced Searching Tutorial

5. Download Citations

Selected citations and/or entire sets of search results can be downloaded from the database into a citation management tool. If you are conducting a systematic review that will require reporting according to PRISMA standards, a citation manager can help you keep track of the number of articles that came from each database, as well as the number of duplicate records.

In Zotero, you can create a Collection for the combined results set, and sub-collections for the results from each database you search. You can then use Zotero's 'Duplicate Items" function to find and merge duplicate records.

- Citation Managers - General Guide

6. Abstract and Analyze

- Migrate citations to data collection/extraction tool

- Screen Title/Abstracts for inclusion/exclusion

- Screen and appraise full text for relevance, methods,

- Resolve disagreements by consensus

Covidence is a web-based tool that enables you to work with a team to screen titles/abstracts and full text for inclusion in your review, as well as extract data from the included studies.

- Covidence Support

- Critical Appraisal Tools

- Data Extraction Tools

7. Create Flow Diagram

The PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses) flow diagram is a visual representation of the flow of records through different phases of a systematic review. It depicts the number of records identified, included and excluded. It is best used in conjunction with the PRISMA checklist .

Example from: Stotz, S. A., McNealy, K., Begay, R. L., DeSanto, K., Manson, S. M., & Moore, K. R. (2021). Multi-level diabetes prevention and treatment interventions for Native people in the USA and Canada: A scoping review. Current Diabetes Reports, 2 (11), 46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11892-021-01414-3

- PRISMA Flow Diagram Generator (ShinyApp.io, Haddaway et al. )

- PRISMA Diagram Templates (Word and PDF)

- Make a copy of the file to fill out the template

- Image can be downloaded as PDF, PNG, JPG, or SVG

- Covidence generates a PRISMA diagram that is automatically updated as records move through the review phases

8. Synthesize & Report Results

There are a number of reporting guideline available to guide the synthesis and reporting of results in systematic literature reviews.

It is common to organize findings in a matrix, also known as a Table of Evidence (ToE).

- Reporting Guidelines for Systematic Reviews

- Download a sample template of a health sciences review matrix (GoogleSheets)

Steps modified from:

Cook, D. A., & West, C. P. (2012). Conducting systematic reviews in medical education: a stepwise approach. Medical Education , 46 (10), 943–952.

- << Previous: Critical Appraisal Resources

- Next: What are Literature Reviews? >>

- Last Updated: May 31, 2024 10:32 AM

- URL: https://guides.nyu.edu/health

University Libraries

- Ohio University Libraries

- Library Guides

Evidence-based Practice in Healthcare

- Performing a Literature Review

- EBP Tutorials

- Question- PICO

- Definitions

- Systematic Reviews

- Levels of Evidence

- Finding Evidence

- Filter by Study Type

- Too Much or Too Little?

- Critical Appraisal

- Quality Improvement (QI)

- Contact - Need Help?

Hanna's Performing a qualitity literature review presentation slides

- Link to the PPT slides via OneDrive anyone can view

Characteristics of a Good Literature Review in Health & Medicine

Clear Objectives and Research Questions : The review should start with clearly defined objectives and research questions that guide the scope and focus of the review.

Comprehensive Coverage : Include a wide range of relevant sources, such as research articles, review papers, clinical guidelines, and books. Aim for a broad understanding of the topic, covering historical developments and current advancements. To do this, an intentional and minimally biased search strategy.

- Link to relevant databases to consider for a comprehensive search (search 2+ databases)

- Link to the video "Searching your Topic: Strategies and Efficiencies" by Hanna Schmillen

- Link to the worksheet "From topic, to PICO, to search strategy" to help researchers work through their topic into an intentional search strategy by Hanna Schmillen

Transparency and Replicability : The review process, search strategy, should be transparent, with detailed documentation of all steps taken. This allows others to replicate the review or update it in the future.

Appraisal of Studies Included : Each included study should be critically appraised for methodological quality and relevance. Use standardized appraisal tools to assess the risk of bias and the quality of evidence.

- Link to the video " Evaluating Health Research" by Hanna Schmillen

- Link to evaluating and appraising studies tab, which includes a rubric and checklists

Clear Synthesis and Discussion of Findings : The review should provide a thorough discussion of the findings, including any patterns, relationships, or trends identified in the literature. Address the strengths and limitations of the reviewed studies and the review itself. Present findings in a balanced and unbiased manner, avoiding over interpretation or selective reporting of results.

Implications for Practice and Research : The review should highlight the practical implications of the findings for medical practice and policy. It should also identify gaps in the current literature and suggest areas for future research.

Referencing and Citation : Use proper citation practices to credit original sources. Provide a comprehensive reference list to guide readers to the original studies.

- Link to Citation Style Guide, includes tab about Zotero

Note: A literature review is not a systematic review. For more information about systematic reviews and different types of evidence synthesis projects, see the Evidence Synthesis guide .

- << Previous: Quality Improvement (QI)

- Next: Contact - Need Help? >>

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- PLoS Comput Biol

- v.9(7); 2013 Jul

Ten Simple Rules for Writing a Literature Review

Marco pautasso.

1 Centre for Functional and Evolutionary Ecology (CEFE), CNRS, Montpellier, France

2 Centre for Biodiversity Synthesis and Analysis (CESAB), FRB, Aix-en-Provence, France

Literature reviews are in great demand in most scientific fields. Their need stems from the ever-increasing output of scientific publications [1] . For example, compared to 1991, in 2008 three, eight, and forty times more papers were indexed in Web of Science on malaria, obesity, and biodiversity, respectively [2] . Given such mountains of papers, scientists cannot be expected to examine in detail every single new paper relevant to their interests [3] . Thus, it is both advantageous and necessary to rely on regular summaries of the recent literature. Although recognition for scientists mainly comes from primary research, timely literature reviews can lead to new synthetic insights and are often widely read [4] . For such summaries to be useful, however, they need to be compiled in a professional way [5] .

When starting from scratch, reviewing the literature can require a titanic amount of work. That is why researchers who have spent their career working on a certain research issue are in a perfect position to review that literature. Some graduate schools are now offering courses in reviewing the literature, given that most research students start their project by producing an overview of what has already been done on their research issue [6] . However, it is likely that most scientists have not thought in detail about how to approach and carry out a literature review.

Reviewing the literature requires the ability to juggle multiple tasks, from finding and evaluating relevant material to synthesising information from various sources, from critical thinking to paraphrasing, evaluating, and citation skills [7] . In this contribution, I share ten simple rules I learned working on about 25 literature reviews as a PhD and postdoctoral student. Ideas and insights also come from discussions with coauthors and colleagues, as well as feedback from reviewers and editors.

Rule 1: Define a Topic and Audience

How to choose which topic to review? There are so many issues in contemporary science that you could spend a lifetime of attending conferences and reading the literature just pondering what to review. On the one hand, if you take several years to choose, several other people may have had the same idea in the meantime. On the other hand, only a well-considered topic is likely to lead to a brilliant literature review [8] . The topic must at least be:

- interesting to you (ideally, you should have come across a series of recent papers related to your line of work that call for a critical summary),

- an important aspect of the field (so that many readers will be interested in the review and there will be enough material to write it), and

- a well-defined issue (otherwise you could potentially include thousands of publications, which would make the review unhelpful).

Ideas for potential reviews may come from papers providing lists of key research questions to be answered [9] , but also from serendipitous moments during desultory reading and discussions. In addition to choosing your topic, you should also select a target audience. In many cases, the topic (e.g., web services in computational biology) will automatically define an audience (e.g., computational biologists), but that same topic may also be of interest to neighbouring fields (e.g., computer science, biology, etc.).

Rule 2: Search and Re-search the Literature

After having chosen your topic and audience, start by checking the literature and downloading relevant papers. Five pieces of advice here:

- keep track of the search items you use (so that your search can be replicated [10] ),

- keep a list of papers whose pdfs you cannot access immediately (so as to retrieve them later with alternative strategies),

- use a paper management system (e.g., Mendeley, Papers, Qiqqa, Sente),

- define early in the process some criteria for exclusion of irrelevant papers (these criteria can then be described in the review to help define its scope), and

- do not just look for research papers in the area you wish to review, but also seek previous reviews.

The chances are high that someone will already have published a literature review ( Figure 1 ), if not exactly on the issue you are planning to tackle, at least on a related topic. If there are already a few or several reviews of the literature on your issue, my advice is not to give up, but to carry on with your own literature review,

The bottom-right situation (many literature reviews but few research papers) is not just a theoretical situation; it applies, for example, to the study of the impacts of climate change on plant diseases, where there appear to be more literature reviews than research studies [33] .

- discussing in your review the approaches, limitations, and conclusions of past reviews,

- trying to find a new angle that has not been covered adequately in the previous reviews, and

- incorporating new material that has inevitably accumulated since their appearance.

When searching the literature for pertinent papers and reviews, the usual rules apply:

- be thorough,

- use different keywords and database sources (e.g., DBLP, Google Scholar, ISI Proceedings, JSTOR Search, Medline, Scopus, Web of Science), and

- look at who has cited past relevant papers and book chapters.

Rule 3: Take Notes While Reading

If you read the papers first, and only afterwards start writing the review, you will need a very good memory to remember who wrote what, and what your impressions and associations were while reading each single paper. My advice is, while reading, to start writing down interesting pieces of information, insights about how to organize the review, and thoughts on what to write. This way, by the time you have read the literature you selected, you will already have a rough draft of the review.

Of course, this draft will still need much rewriting, restructuring, and rethinking to obtain a text with a coherent argument [11] , but you will have avoided the danger posed by staring at a blank document. Be careful when taking notes to use quotation marks if you are provisionally copying verbatim from the literature. It is advisable then to reformulate such quotes with your own words in the final draft. It is important to be careful in noting the references already at this stage, so as to avoid misattributions. Using referencing software from the very beginning of your endeavour will save you time.

Rule 4: Choose the Type of Review You Wish to Write

After having taken notes while reading the literature, you will have a rough idea of the amount of material available for the review. This is probably a good time to decide whether to go for a mini- or a full review. Some journals are now favouring the publication of rather short reviews focusing on the last few years, with a limit on the number of words and citations. A mini-review is not necessarily a minor review: it may well attract more attention from busy readers, although it will inevitably simplify some issues and leave out some relevant material due to space limitations. A full review will have the advantage of more freedom to cover in detail the complexities of a particular scientific development, but may then be left in the pile of the very important papers “to be read” by readers with little time to spare for major monographs.

There is probably a continuum between mini- and full reviews. The same point applies to the dichotomy of descriptive vs. integrative reviews. While descriptive reviews focus on the methodology, findings, and interpretation of each reviewed study, integrative reviews attempt to find common ideas and concepts from the reviewed material [12] . A similar distinction exists between narrative and systematic reviews: while narrative reviews are qualitative, systematic reviews attempt to test a hypothesis based on the published evidence, which is gathered using a predefined protocol to reduce bias [13] , [14] . When systematic reviews analyse quantitative results in a quantitative way, they become meta-analyses. The choice between different review types will have to be made on a case-by-case basis, depending not just on the nature of the material found and the preferences of the target journal(s), but also on the time available to write the review and the number of coauthors [15] .

Rule 5: Keep the Review Focused, but Make It of Broad Interest

Whether your plan is to write a mini- or a full review, it is good advice to keep it focused 16 , 17 . Including material just for the sake of it can easily lead to reviews that are trying to do too many things at once. The need to keep a review focused can be problematic for interdisciplinary reviews, where the aim is to bridge the gap between fields [18] . If you are writing a review on, for example, how epidemiological approaches are used in modelling the spread of ideas, you may be inclined to include material from both parent fields, epidemiology and the study of cultural diffusion. This may be necessary to some extent, but in this case a focused review would only deal in detail with those studies at the interface between epidemiology and the spread of ideas.

While focus is an important feature of a successful review, this requirement has to be balanced with the need to make the review relevant to a broad audience. This square may be circled by discussing the wider implications of the reviewed topic for other disciplines.

Rule 6: Be Critical and Consistent

Reviewing the literature is not stamp collecting. A good review does not just summarize the literature, but discusses it critically, identifies methodological problems, and points out research gaps [19] . After having read a review of the literature, a reader should have a rough idea of:

- the major achievements in the reviewed field,

- the main areas of debate, and

- the outstanding research questions.

It is challenging to achieve a successful review on all these fronts. A solution can be to involve a set of complementary coauthors: some people are excellent at mapping what has been achieved, some others are very good at identifying dark clouds on the horizon, and some have instead a knack at predicting where solutions are going to come from. If your journal club has exactly this sort of team, then you should definitely write a review of the literature! In addition to critical thinking, a literature review needs consistency, for example in the choice of passive vs. active voice and present vs. past tense.

Rule 7: Find a Logical Structure

Like a well-baked cake, a good review has a number of telling features: it is worth the reader's time, timely, systematic, well written, focused, and critical. It also needs a good structure. With reviews, the usual subdivision of research papers into introduction, methods, results, and discussion does not work or is rarely used. However, a general introduction of the context and, toward the end, a recapitulation of the main points covered and take-home messages make sense also in the case of reviews. For systematic reviews, there is a trend towards including information about how the literature was searched (database, keywords, time limits) [20] .

How can you organize the flow of the main body of the review so that the reader will be drawn into and guided through it? It is generally helpful to draw a conceptual scheme of the review, e.g., with mind-mapping techniques. Such diagrams can help recognize a logical way to order and link the various sections of a review [21] . This is the case not just at the writing stage, but also for readers if the diagram is included in the review as a figure. A careful selection of diagrams and figures relevant to the reviewed topic can be very helpful to structure the text too [22] .

Rule 8: Make Use of Feedback

Reviews of the literature are normally peer-reviewed in the same way as research papers, and rightly so [23] . As a rule, incorporating feedback from reviewers greatly helps improve a review draft. Having read the review with a fresh mind, reviewers may spot inaccuracies, inconsistencies, and ambiguities that had not been noticed by the writers due to rereading the typescript too many times. It is however advisable to reread the draft one more time before submission, as a last-minute correction of typos, leaps, and muddled sentences may enable the reviewers to focus on providing advice on the content rather than the form.

Feedback is vital to writing a good review, and should be sought from a variety of colleagues, so as to obtain a diversity of views on the draft. This may lead in some cases to conflicting views on the merits of the paper, and on how to improve it, but such a situation is better than the absence of feedback. A diversity of feedback perspectives on a literature review can help identify where the consensus view stands in the landscape of the current scientific understanding of an issue [24] .

Rule 9: Include Your Own Relevant Research, but Be Objective

In many cases, reviewers of the literature will have published studies relevant to the review they are writing. This could create a conflict of interest: how can reviewers report objectively on their own work [25] ? Some scientists may be overly enthusiastic about what they have published, and thus risk giving too much importance to their own findings in the review. However, bias could also occur in the other direction: some scientists may be unduly dismissive of their own achievements, so that they will tend to downplay their contribution (if any) to a field when reviewing it.

In general, a review of the literature should neither be a public relations brochure nor an exercise in competitive self-denial. If a reviewer is up to the job of producing a well-organized and methodical review, which flows well and provides a service to the readership, then it should be possible to be objective in reviewing one's own relevant findings. In reviews written by multiple authors, this may be achieved by assigning the review of the results of a coauthor to different coauthors.

Rule 10: Be Up-to-Date, but Do Not Forget Older Studies

Given the progressive acceleration in the publication of scientific papers, today's reviews of the literature need awareness not just of the overall direction and achievements of a field of inquiry, but also of the latest studies, so as not to become out-of-date before they have been published. Ideally, a literature review should not identify as a major research gap an issue that has just been addressed in a series of papers in press (the same applies, of course, to older, overlooked studies (“sleeping beauties” [26] )). This implies that literature reviewers would do well to keep an eye on electronic lists of papers in press, given that it can take months before these appear in scientific databases. Some reviews declare that they have scanned the literature up to a certain point in time, but given that peer review can be a rather lengthy process, a full search for newly appeared literature at the revision stage may be worthwhile. Assessing the contribution of papers that have just appeared is particularly challenging, because there is little perspective with which to gauge their significance and impact on further research and society.

Inevitably, new papers on the reviewed topic (including independently written literature reviews) will appear from all quarters after the review has been published, so that there may soon be the need for an updated review. But this is the nature of science [27] – [32] . I wish everybody good luck with writing a review of the literature.

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to M. Barbosa, K. Dehnen-Schmutz, T. Döring, D. Fontaneto, M. Garbelotto, O. Holdenrieder, M. Jeger, D. Lonsdale, A. MacLeod, P. Mills, M. Moslonka-Lefebvre, G. Stancanelli, P. Weisberg, and X. Xu for insights and discussions, and to P. Bourne, T. Matoni, and D. Smith for helpful comments on a previous draft.

Funding Statement

This work was funded by the French Foundation for Research on Biodiversity (FRB) through its Centre for Synthesis and Analysis of Biodiversity data (CESAB), as part of the NETSEED research project. The funders had no role in the preparation of the manuscript.

Nursing: How to Write a Literature Review

- Traditional or Narrative Literature Review

Literature Review Overview

What is a Literature Review? Why Are They Important?

A literature review is important because it presents the "state of the science" or accumulated knowledge on a specific topic. It summarizes, analyzes, and compares the available research, reporting study strengths and weaknesses, results, gaps in the research, conclusions, and authors’ interpretations.

Tips and techniques for conducting a literature review are described more fully in the subsequent boxes:

- Literature review steps

- Strategies for organizing the information for your review

- Literature reviews sections

- In-depth resources to assist in writing a literature review

- Templates to start your review

- Literature review examples

Literature Review Steps

Graphic used with permission: Torres, E. Librarian, Hawai'i Pacific University

1. Choose a topic and define your research question

- Try to choose a topic of interest. You will be working with this subject for several weeks to months.

- Ideas for topics can be found by scanning medical news sources (e.g MedPage Today), journals / magazines, work experiences, interesting patient cases, or family or personal health issues.

- Do a bit of background reading on topic ideas to familiarize yourself with terminology and issues. Note the words and terms that are used.

- Develop a focused research question using PICO(T) or other framework (FINER, SPICE, etc - there are many options) to help guide you.

- Run a few sample database searches to make sure your research question is not too broad or too narrow.

- If possible, discuss your topic with your professor.

2. Determine the scope of your review

The scope of your review will be determined by your professor during your program. Check your assignment requirements for parameters for the Literature Review.

- How many studies will you need to include?

- How many years should it cover? (usually 5-7 depending on the professor)

- For the nurses, are you required to limit to nursing literature?

3. Develop a search plan

- Determine which databases to search. This will depend on your topic. If you are not sure, check your program specific library website (Physician Asst / Nursing / Health Services Admin) for recommendations.

- Create an initial search string using the main concepts from your research (PICO, etc) question. Include synonyms and related words connected by Boolean operators

- Contact your librarian for assistance, if needed.

4. Conduct searches and find relevant literature

- Keep notes as you search - tracking keywords and search strings used in each database in order to avoid wasting time duplicating a search that has already been tried

- Read abstracts and write down new terms to search as you find them

- Check MeSH or other subject headings listed in relevant articles for additional search terms

- Scan author provided keywords if available

- Check the references of relevant articles looking for other useful articles (ancestry searching)

- Check articles that have cited your relevant article for more useful articles (descendancy searching). Both PubMed and CINAHL offer Cited By links

- Revise the search to broaden or narrow your topic focus as you peruse the available literature

- Conducting a literature search is a repetitive process. Searches can be revised and re-run multiple times during the process.

- Track the citations for your relevant articles in a software citation manager such as RefWorks, Zotero, or Mendeley

5. Review the literature

- Read the full articles. Do not rely solely on the abstracts. Authors frequently cannot include all results within the confines of an abstract. Exclude articles that do not address your research question.

- While reading, note research findings relevant to your project and summarize. Are the findings conflicting? There are matrices available than can help with organization. See the Organizing Information box below.

- Critique / evaluate the quality of the articles, and record your findings in your matrix or summary table. Tools are available to prompt you what to look for. (See Resources for Appraising a Research Study box on the HSA, Nursing , and PA guides )

- You may need to revise your search and re-run it based on your findings.

6. Organize and synthesize

- Compile the findings and analysis from each resource into a single narrative.

- Using an outline can be helpful. Start broad, addressing the overall findings and then narrow, discussing each resource and how it relates to your question and to the other resources.

- Cite as you write to keep sources organized.

- Write in structured paragraphs using topic sentences and transition words to draw connections, comparisons, and contrasts.

- Don't present one study after another, but rather relate one study's findings to another. Speak to how the studies are connected and how they relate to your work.

Organizing Information

Options to assist in organizing sources and information :

1. Synthesis Matrix

- helps provide overview of the literature

- information from individual sources is entered into a grid to enable writers to discern patterns and themes

- article summary, analysis, or results

- thoughts, reflections, or issues

- each reference gets its own row

- mind maps, concept maps, flowcharts

- at top of page record PICO or research question

- record major concepts / themes from literature

- list concepts that branch out from major concepts underneath - keep going downward hierarchically, until most specific ideas are recorded

- enclose concepts in circles and connect the concept with lines - add brief explanation as needed

3. Summary Table

- information is recorded in a grid to help with recall and sorting information when writing

- allows comparing and contrasting individual studies easily

- purpose of study

- methodology (study population, data collection tool)

Efron, S. E., & Ravid, R. (2019). Writing the literature review : A practical guide . Guilford Press.

Literature Review Sections

- Lit reviews can be part of a larger paper / research study or they can be the focus of the paper

- Lit reviews focus on research studies to provide evidence

- New topics may not have much that has been published

* The sections included may depend on the purpose of the literature review (standalone paper or section within a research paper)

Standalone Literature Review (aka Narrative Review):

- presents your topic or PICO question

- includes the why of the literature review and your goals for the review.

- provides background for your the topic and previews the key points

- Narrative Reviews: tmay not have an explanation of methods.

- include where the search was conducted (which databases) what subject terms or keywords were used, and any limits or filters that were applied and why - this will help others re-create the search

- describe how studies were analyzed for inclusion or exclusion

- review the purpose and answer the research question

- thematically - using recurring themes in the literature

- chronologically - present the development of the topic over time

- methodological - compare and contrast findings based on various methodologies used to research the topic (e.g. qualitative vs quantitative, etc.)

- theoretical - organized content based on various theories

- provide an overview of the main points of each source then synthesize the findings into a coherent summary of the whole

- present common themes among the studies

- compare and contrast the various study results

- interpret the results and address the implications of the findings

- do the results support the original hypothesis or conflict with it

- provide your own analysis and interpretation (eg. discuss the significance of findings; evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of the studies, noting any problems)

- discuss common and unusual patterns and offer explanations

- stay away from opinions, personal biases and unsupported recommendations

- summarize the key findings and relate them back to your PICO/research question

- note gaps in the research and suggest areas for further research

- this section should not contain "new" information that had not been previously discussed in one of the sections above

- provide a list of all the studies and other sources used in proper APA 7

Literature Review as Part of a Research Study Manuscript:

- Compares the study with other research and includes how a study fills a gap in the research.

- Focus on the body of the review which includes the synthesized Findings and Discussion

Literature Reviews vs Systematic Reviews

Systematic Reviews are NOT the same as a Literature Review:

Literature Reviews:

- Literature reviews may or may not follow strict systematic methods to find, select, and analyze articles, but rather they selectively and broadly review the literature on a topic

- Research included in a Literature Review can be "cherry-picked" and therefore, can be very subjective

Systematic Reviews:

- Systemic reviews are designed to provide a comprehensive summary of the evidence for a focused research question

- rigorous and strictly structured, using standardized reporting guidelines (e.g. PRISMA, see link below)

- uses exhaustive, systematic searches of all relevant databases

- best practice dictates search strategies are peer reviewed

- uses predetermined study inclusion and exclusion criteria in order to minimize bias

- aims to capture and synthesize all literature (including unpublished research - grey literature) that meet the predefined criteria on a focused topic resulting in high quality evidence

Literature Review Examples

- Breastfeeding initiation and support: A literature review of what women value and the impact of early discharge (2017). Women and Birth : Journal of the Australian College of Midwives

- Community-based participatory research to promote healthy diet and nutrition and prevent and control obesity among African-Americans: A literature review (2017). Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities

- Vitamin D deficiency in individuals with a spinal cord injury: A literature review (2017). Spinal Cord

Resources for Writing a Literature Review

These sources have been used in developing this guide.

Resources Used on This Page

Aveyard, H. (2010). Doing a literature review in health and social care : A practical guide . McGraw-Hill Education.

Purdue Online Writing Lab. (n.d.). Writing a literature review . Purdue University. https://owl.purdue.edu/owl/research_and_citation/conducting_research/writing_a_literature_review.html

Torres, E. (2021, October 21). Nursing - graduate studies research guide: Literature review. Hawai'i Pacific University Libraries. Retrieved January 27, 2022, from https://hpu.libguides.com/c.php?g=543891&p=3727230

- << Previous: General Writing Support

- Next: Creating & Printing Posters >>

- Last Updated: May 24, 2024 12:34 PM

- URL: https://udmercy.libguides.com/nursing

Harvey Cushing/John Hay Whitney Medical Library

- Collections

- Research Help

YSN Doctoral Programs: Steps in Conducting a Literature Review

- Biomedical Databases

- Global (Public Health) Databases

- Soc. Sci., History, and Law Databases

- Grey Literature

- Trials Registers

- Data and Statistics

- Public Policy

- Google Tips

- Recommended Books

- Steps in Conducting a Literature Review

What is a literature review?

A literature review is an integrated analysis -- not just a summary-- of scholarly writings and other relevant evidence related directly to your research question. That is, it represents a synthesis of the evidence that provides background information on your topic and shows a association between the evidence and your research question.

A literature review may be a stand alone work or the introduction to a larger research paper, depending on the assignment. Rely heavily on the guidelines your instructor has given you.

Why is it important?

A literature review is important because it:

- Explains the background of research on a topic.

- Demonstrates why a topic is significant to a subject area.

- Discovers relationships between research studies/ideas.

- Identifies major themes, concepts, and researchers on a topic.

- Identifies critical gaps and points of disagreement.

- Discusses further research questions that logically come out of the previous studies.

APA7 Style resources

APA Style Blog - for those harder to find answers

1. Choose a topic. Define your research question.

Your literature review should be guided by your central research question. The literature represents background and research developments related to a specific research question, interpreted and analyzed by you in a synthesized way.

- Make sure your research question is not too broad or too narrow. Is it manageable?

- Begin writing down terms that are related to your question. These will be useful for searches later.

- If you have the opportunity, discuss your topic with your professor and your class mates.

2. Decide on the scope of your review

How many studies do you need to look at? How comprehensive should it be? How many years should it cover?

- This may depend on your assignment. How many sources does the assignment require?

3. Select the databases you will use to conduct your searches.

Make a list of the databases you will search.

Where to find databases:

- use the tabs on this guide

- Find other databases in the Nursing Information Resources web page

- More on the Medical Library web page

- ... and more on the Yale University Library web page

4. Conduct your searches to find the evidence. Keep track of your searches.

- Use the key words in your question, as well as synonyms for those words, as terms in your search. Use the database tutorials for help.

- Save the searches in the databases. This saves time when you want to redo, or modify, the searches. It is also helpful to use as a guide is the searches are not finding any useful results.

- Review the abstracts of research studies carefully. This will save you time.

- Use the bibliographies and references of research studies you find to locate others.

- Check with your professor, or a subject expert in the field, if you are missing any key works in the field.

- Ask your librarian for help at any time.

- Use a citation manager, such as EndNote as the repository for your citations. See the EndNote tutorials for help.

Review the literature

Some questions to help you analyze the research:

- What was the research question of the study you are reviewing? What were the authors trying to discover?

- Was the research funded by a source that could influence the findings?

- What were the research methodologies? Analyze its literature review, the samples and variables used, the results, and the conclusions.

- Does the research seem to be complete? Could it have been conducted more soundly? What further questions does it raise?

- If there are conflicting studies, why do you think that is?

- How are the authors viewed in the field? Has this study been cited? If so, how has it been analyzed?

Tips:

- Review the abstracts carefully.

- Keep careful notes so that you may track your thought processes during the research process.

- Create a matrix of the studies for easy analysis, and synthesis, across all of the studies.

- << Previous: Recommended Books

- Last Updated: Jan 4, 2024 10:52 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.yale.edu/YSNDoctoral

The Sheridan Libraries

- Public Health

- Sheridan Libraries

- Literature Reviews + Annotating

- How to Access Full Text

- Background Information

- Books, E-books, Dissertations

- Articles, News, Who Cited This, More

- Google Scholar and Google Books

- PUBMED and EMBASE

- Statistics -- United States

- Statistics -- Worldwide

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Citing Sources This link opens in a new window

- Copyright This link opens in a new window

- Evaluating Information This link opens in a new window

- RefWorks Guide and Help This link opens in a new window

- Epidemic Proportions

- Environment and Your Health, AS 280.335, Spring 2024

- Honors in Public Health, AS280.495, Fall 23-Spr 2024

- Intro to Public Health, AS280.101, Spring 2024

- Research Methods in Public Health, AS280.240, Spring 2024

- Social+Behavioral Determinants of Health, AS280.355, Spring 2024

- Feedback (for class use only)

Literature Reviews

- Organizing/Synthesizing

- Peer Review

- Ulrich's -- One More Way To Find Peer-reviewed Papers

"Literature review," "systematic literature review," "integrative literature review" -- these are terms used in different disciplines for basically the same thing -- a rigorous examination of the scholarly literature about a topic (at different levels of rigor, and with some different emphases).

1. Our library's guide to Writing a Literature Review

2. Other helpful sites

- Writing Center at UNC (Chapel Hill) -- A very good guide about lit reviews and how to write them

- Literature Review: Synthesizing Multiple Sources (LSU, June 2011 but good; PDF) -- Planning, writing, and tips for revising your paper

3. Welch Library's list of the types of expert reviews

Doing a good job of organizing your information makes writing about it a lot easier.

You can organize your sources using a citation manager, such as refworks , or use a matrix (if you only have a few references):.

- Use Google Sheets, Word, Excel, or whatever you prefer to create a table

- The column headings should include the citation information, and the main points that you want to track, as shown

Synthesizing your information is not just summarizing it. Here are processes and examples about how to combine your sources into a good piece of writing:

- Purdue OWL's Synthesizing Sources

- Synthesizing Sources (California State University, Northridge)

Annotated Bibliography

An "annotation" is a note or comment. An "annotated bibliography" is a "list of citations to books, articles, and [other items]. Each citation is followed by a brief...descriptive and evaluative paragraph, [whose purpose is] to inform the reader of the relevance, accuracy, and quality of the sources cited."*

- Sage Research Methods (database) --> Empirical Research and Writing (ebook) -- Chapter 3: Doing Pre-research

- Purdue's OWL (Online Writing Lab) includes definitions and samples of annotations

- Cornell's guide * to writing annotated bibliographies

* Thank you to Olin Library Reference, Research & Learning Services, Cornell University Library, Ithaca, NY, USA https://guides.library.cornell.edu/annotatedbibliography

What does "peer-reviewed" mean?

- If an article has been peer-reviewed before being published, it means that the article has been read by other people in the same field of study ("peers").

- The author's reviewers have commented on the article, not only noting typos and possible errors, but also giving a judgment about whether or not the article should be published by the journal to which it was submitted.

How do I find "peer-reviewed" materials?

- Most of the the research articles in scholarly journals are peer-reviewed.

- Many databases allow you to check a box that says "peer-reviewed," or to see which results in your list of results are from peer-reviewed sources. Some of the databases that provide this are Academic Search Ultimate, CINAHL, PsycINFO, and Sociological Abstracts.

What kinds of materials are *not* peer-reviewed?

- open web pages

- most newspapers, newsletters, and news items in journals

- letters to the editor

- press releases

- columns and blogs

- book reviews

- anything in a popular magazine (e.g., Time, Newsweek, Glamour, Men's Health)

If a piece of information wasn't peer-reviewed, does that mean that I can't trust it at all?

No; sometimes you can. For example, the preprints submitted to well-known sites such as arXiv (mainly covering physics) and CiteSeerX (mainly covering computer science) are probably trustworthy, as are the databases and web pages produced by entities such as the National Library of Medicine, the Smithsonian Institution, and the American Cancer Society.

Is this paper peer-reviewed? Ulrichsweb will tell you.

1) On the library home page , choose "Articles and Databases" --> "Databases" --> Ulrichsweb

2) Put in the title of the JOURNAL (not the article), in quotation marks so all the words are next to each other

3) Mouse over the black icon, and you'll see that it means "refereed" (which means peer-reviewed, because it's been looked at by referees or reviewers). This journal is not peer-reviewed, because none of the formats have a black icon next to it:

- << Previous: Evaluating Information

- Next: RefWorks Guide and Help >>

- Last Updated: May 13, 2024 10:04 AM

- URL: https://guides.library.jhu.edu/public-health

- Cancer Nursing Practice

- Emergency Nurse

- Evidence-Based Nursing

- Learning Disability Practice

- Mental Health Practice

- Nurse Researcher

- Nursing Children and Young People

- Nursing Management

- Nursing Older People

- Nursing Standard

- Primary Health Care

- RCN Nursing Awards

- Nursing Live

- Nursing Careers and Job Fairs

- CPD webinars on-demand

- --> Advanced -->

- Clinical articles

- Expert advice

- Career advice

- Revalidation

Book review Previous Next

Doing a literature review in nursing, health and social care (second edition), claire lee paediatric research nurse, department of paediatric gastroenterology, addenbrooke’s hospital, cambridge.

This book provides a concise and informative guide to the process of literature review in nursing, health and social care, and is applicable to students and professionals.

Nurse Researcher . 24, 4, 8-8. doi: 10.7748/nr.24.4.8.s3

User not found

Want to read more?

Already have access log in, 3-month trial offer for £5.25/month.

- Unlimited access to all 10 RCNi Journals

- RCNi Learning featuring over 175 modules to easily earn CPD time

- NMC-compliant RCNi Revalidation Portfolio to stay on track with your progress

- Personalised newsletters tailored to your interests

- A customisable dashboard with over 200 topics

Alternatively, you can purchase access to this article for the next seven days. Buy now

Are you a student? Our student subscription has content especially for you. Find out more

22 March 2017 / Vol 24 issue 4

TABLE OF CONTENTS

DIGITAL EDITION

- LATEST ISSUE

- SIGN UP FOR E-ALERT

- WRITE FOR US

- PERMISSIONS

Share article: Doing a Literature Review in Nursing, Health and Social Care (Second edition)

We use cookies on this site to enhance your user experience.

By clicking any link on this page you are giving your consent for us to set cookies.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Open access

- Published: 03 June 2024

The effectiveness of digital twins in promoting precision health across the entire population: a systematic review

- Mei-di Shen 1 ,

- Si-bing Chen 2 &

- Xiang-dong Ding ORCID: orcid.org/0009-0001-1925-0654 2

npj Digital Medicine volume 7 , Article number: 145 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

38 Accesses

2 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Public health

- Risk factors

- Signs and symptoms

Digital twins represent a promising technology within the domain of precision healthcare, offering significant prospects for individualized medical interventions. Existing systematic reviews, however, mainly focus on the technological dimensions of digital twins, with a limited exploration of their impact on health-related outcomes. Therefore, this systematic review aims to explore the efficacy of digital twins in improving precision healthcare at the population level. The literature search for this study encompassed PubMed, Embase, Web of Science, Cochrane Library, CINAHL, SinoMed, CNKI, and Wanfang Database to retrieve potentially relevant records. Patient health-related outcomes were synthesized employing quantitative content analysis, whereas the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) scales were used to evaluate the quality and potential bias inherent in each selected study. Following established inclusion and exclusion criteria, 12 studies were screened from an initial 1321 records for further analysis. These studies included patients with various conditions, including cancers, type 2 diabetes, multiple sclerosis, heart failure, qi deficiency, post-hepatectomy liver failure, and dental issues. The review coded three types of interventions: personalized health management, precision individual therapy effects, and predicting individual risk, leading to a total of 45 outcomes being measured. The collective effectiveness of these outcomes at the population level was calculated at 80% (36 out of 45). No studies exhibited unacceptable differences in quality. Overall, employing digital twins in precision health demonstrates practical advantages, warranting its expanded use to facilitate the transition from the development phase to broad application.

PROSPERO registry: CRD42024507256.

Similar content being viewed by others

Digital twins for health: a scoping review

Digital twins in medicine

The health digital twin to tackle cardiovascular disease—a review of an emerging interdisciplinary field

Introduction.

Precision health represents a paradigm shift from the conventional “one size fits all” medical approach, focusing on specific diagnosis, treatment, and health management by incorporating individualized factors such as omics data, clinical information, and health outcomes 1 , 2 . This approach significantly impacts various diseases, potentially improving overall health while reducing healthcare costs 3 , 4 . Within this context, digital twins emerged as a promising technology 5 , creating digital replicas of the human body through two key steps: building mappings and enabling dynamic evolution 6 . Unlike traditional data mining methods, digital twins consider individual variability, providing continuous, dynamic recommendations for clinical practice 7 . This approach has gained significant attention among researchers, highlighting its potential applications in advancing precision health.

Several systematic reviews have explored the advancement of digital twins within the healthcare sector. One rapid review 8 identified four core functionalities of digital twins in healthcare management: safety management, information management, health management/well-being promotion, and operational control. Another systematic review 9 , through an analysis of 22 selected publications, summarized the diverse application scenarios of digital twins in healthcare, confirming their potential in continuous monitoring, personalized therapy, and hospital management. Furthermore, a quantitative review 10 assessed 94 high-quality articles published from 2018 to 2022, revealing a primary focus on technological advancements (such as artificial intelligence and the Internet of Things) and application scenarios (including personalized, precise, and real-time healthcare solutions), thus highlighting the pivotal role of digital twins technology in the field of precision health. Another systematic review 11 , incorporating 18 framework papers or reviews, underscored the need for ongoing research into digital twins’ healthcare applications, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic. Moreover, a systematic review 12 on the application of digital twins in cardiovascular diseases presented proof-of-concept and data-driven approaches, offering valuable insights for implementing digital twins in this specific medical area.

While the existing literature offers valuable insights into the technological aspects of digital twins in healthcare, these systematic reviews failed to thoroughly examine the actual impacts on population health. Despite the increasing interest and expanding body of research on digital twins in healthcare, the direct effects on patient health-related outcomes remain unclear. This knowledge gap highlights the need to investigate how digital twins promote and restore patient health, which is vital for advancing precision health technologies. Therefore, the objective of our systematic review is to assess the effectiveness of digital twins in improving health-related outcomes at the population level, providing a clearer understanding of their practical benefits in the context of precision health.

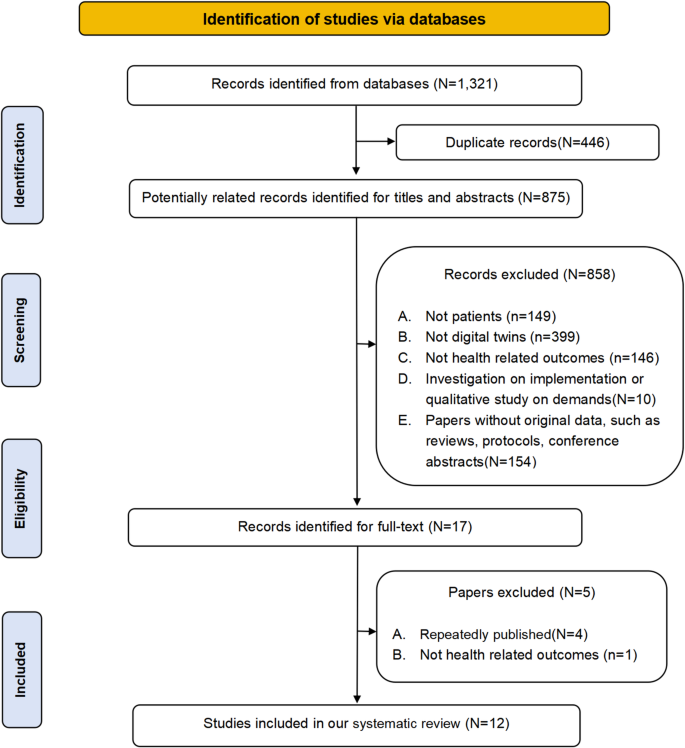

Search results

The selection process for the systematic review is outlined in the PRISMA flow chart (Fig. 1 ). Initially, 1321 records were identified. Of these, 446 duplicates (446/1321, 33.76%) were removed, leaving 875 records (875/1321, 66.24%) for title and abstract screening. Applying the pre-defined inclusion and exclusion criteria led to the exclusion of 858 records (858/875, 98.06%), leaving 17 records (17/875, 1.94%) for full-text review. Further scrutiny resulted in the exclusion of one study (1/17, 5.88%) lacking health-related outcomes and four studies (4/17, 23.53%) with overlapping data. Ultimately, 12 (12/17, 70.59%) original studies 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 were included in the systematic review. Supplementary Table 1 provides a summary of the reasons for exclusion at the full-text reading phase.

Flow chart of included studies in the systematic review.

Study characteristics

The studies included in this systematic review were published between 2021 (2/12, 16.67%) 23 , 24 and 2023 (8/12, 66.67%) 13 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 . Originating from diverse regions, 4/12 studies (33.33%) were from Asia 13 , 14 , 21 , 24 , 5/12 (41.67%) from America 15 , 17 , 19 , 20 , 22 , and 3/12 (25.00%) from Europe 16 , 18 , 23 . The review encompassed various study designs, including randomized controlled trials (1/12, 8.33%) 14 , quasi-experiments (6/12, 50.00%) 13 , 15 , 16 , 18 , 19 , 21 , and cohort studies (5/12, 41.67%) 17 , 20 , 22 , 23 , 24 . The sample sizes ranged from 15 13 to 3500 patients 19 . Five studies assessed the impact of digital twins on virtual patients 15 , 16 , 18 , 19 , 20 , while seven examined their effect on real-world patients 13 , 14 , 17 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 . These patients included had various diseases, including cancer (4/12, 33.33%) 15 , 16 , 19 , 22 , type 2 diabetes (2/12, 16.66%) 13 , 14 , multiple sclerosis (2/12, 16.66%) 17 , 18 , qi deficiency (1/12, 8.33%) 21 , heart failure (1/12, 8.33%) 20 , post-hepatectomy liver failure (1/12, 8.33%) 23 , and dental issues (1/12, 8.33%) 24 . This review coded interventions into three types: personalized health management (3/12, 25.00%) 13 , 14 , 21 , precision individual therapy effects (3/12, 25.00%) 15 , 16 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 22 , and predicting individual risk (3/12, 25.00%) 17 , 23 , 24 , with a total of 45 measured outcomes. Characteristics of the included studies are detailed in Table 1 .

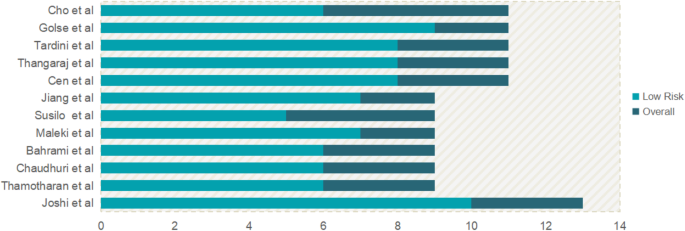

Risk of bias assessment

The risk of bias for the studies included in this review is summarized in Fig. 2 . In the single RCT 14 assessed, 10 out of 13 items received positive responses. Limitations were observed due to incomplete reporting of baseline characteristics and issues with blinding. Among the six quasi-experimental studies evaluated, five (83.33%) 13 , 15 , 16 , 18 , 21 achieved at least six positive responses, indicating an acceptable quality, while one study (16.67%) 19 fell slightly below this threshold with five positive responses. The primary challenges in these quasi-experimental studies were due to the lack of control groups, inadequate baseline comparisons, and limited follow-up reporting. Four out of five (80.00%) 17 , 20 , 22 , 23 of the cohort studies met or exceeded the criterion with at least eight positive responses, demonstrating their acceptable quality. However, one study (20.00%) 24 had a lower score due to incomplete data regarding loss to follow-up and the specifics of the interventions applied. Table 1 elaborates on the specific reasons for these assessments. Despite these concerns, the overall quality of the included studies is considered a generally acceptable risk of bias.

The summary of bias risk via the Joanna Briggs Institute assessment tools.

The impact of digital twins on health-related outcomes among patients

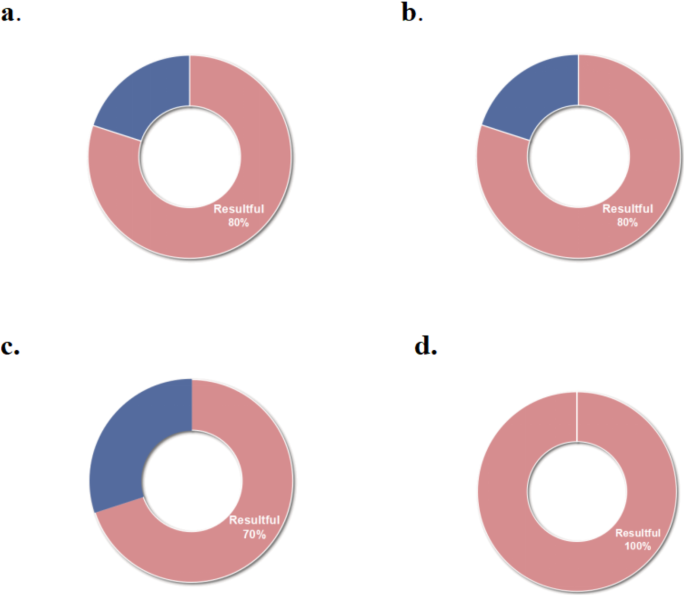

This review includes 12 studies that collectively assessed 45 outcomes, achieving an overall effectiveness rate of 80% (36 out of 45 outcomes), as depicted in Fig. 3a . The digital twins analyzed were coded into three functional categories: personalized health management, precision individual therapy effects, and predicting individual risks. A comprehensive analysis of the effectiveness of digital twins across these categories is provided, detailing the impact and outcomes associated with each function.

a The overall effectiveness of digital twins; b The effectiveness of personalized health management driven by digital twins; c The effectiveness of precision individualized therapy effects driven by digital twins; d The effectiveness of prediction of individual risk driven by digital twins.

The effectiveness of digital twins in personalized health management

In this review, three studies 13 , 14 , 21 employing digital twins for personalized health management reported an effectiveness of 80% (24 out of 30 outcomes), as shown in Fig. 3b . A self-control study 13 involving 15 elderly patients with diabetes, used virtual patient representations based on health information to guide individualized insulin infusion. Over 14 days, this approach improved the time in range (TIR) from 3–75% to 86–97%, decreased hypoglycemia duration from 0–22% to 0–9%, and reduced hyperglycemia time from 0–98% to 0–12%. A 1-year randomized controlled trial 14 with 319 type 2 diabetes patients, implemented personalized digital twins interventions based on nutrition, activity, and sleep. This trial demonstrated significant improvements in Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1C), Homeostatic Model Assessment 2 of Insulin Resistance (HOMA2-IR), Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Liver Fat Score (NAFLD-LFS), and Nonalcoholic Fatty Liver Disease Fibrosis Score (NAFLD-NFS), and other primary outcomes (all, P < 0.001; Table 2 ). However, no significant changes were observed in weight, Alanine Aminotransferase (ALT), Fibrosis-4 Score (FIB4), and AST to Platelet Ratio Index (APRI) (all, P > 0.05). A non-randomized controlled trial 21 introduced a digital twin-based Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) health management platform for patients with qi deficiency. It was found to significantly improve blood pressure, main and secondary TCM symptoms, total TCM symptom scores, and quality of life (all, P < 0.05). Nonetheless, no significant improvements were observed in heart rate and BMI (all, P > 0.05; Table 2 ).

The effectiveness of digital twins in precision individual therapy effects

Six studies 15 , 16 , 18 , 19 , 20 , 22 focused on the precision of individual therapy effects using digital twins, demonstrating a 70% effectiveness rate (7 out of 10 outcomes), as detailed in Fig. 3c . In a self-control study 15 , a data-driven approach was employed to create digital twins, generating 100 virtual patients to predict the potential tumor biology outcomes of radiotherapy regimens with varying contents and doses. This study showed that personalized radiotherapy plans derived from digital twins could extend the median tumor progression time by approximately six days and reduce radiation doses by 16.7%. Bahrami et al. 16 created 3000 virtual patients experiencing cancer pain to administer precision dosing of fentanyl transdermal patch therapy. The intervention led to a 16% decrease in average pain intensity and an additional median pain-free duration of 23 hours, extending from 72 hours in cancer patients. Another quasi-experimental study 18 created 3000 virtual patients with multiple sclerosis to assess the impact of Ocrelizumab. Findings indicated Ocrelizumab can resulted in a reduction in relapses (0.191 [0.143, 0.239]) and lymphopenic adverse events (83.73% vs . 19.9%) compared to a placebo. American researchers 19 developed a quantitative systems pharmacology model using digital twins to identify the optimal dosing for aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphoma patients. This approach resulted in at least a 50% tumor size reduction by day 42 among 3500 virtual patients. A cohort study 20 assessed the 5-year composite cardiovascular outcomes in 2173 virtual patients who were treated with spironolactone or left untreated and indicated no statistically significant inter-group differences (0.85, [0.69–1.04]). Tardini et al. 22 employed digital twins to optimize multi-step treatment for oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma in 134 patients. The optimized treatment selection through digital twins predicted increased survival rates by 3.73 (−0.75, 8.96) and dysphagia rates by 0.75 (−4.48, 6.72) compared to clinician decisions, with no statistical significance.

The effectiveness of digital twins in predicting individual risk

Three studies 17 , 23 , 24 employing digital twins to predict individual patient risks demonstrated a 100% effectiveness rate (5 out of 5 outcomes), as shown in Fig. 3d . A cohort study 17 used digital twins to forecast the onset age for disease-specific brain atrophy in patients with multiple sclerosis. Findings indicated that the onset of progressive brain tissue loss, on average, preceded clinical symptoms by 5-6 years among the 519 patients ( P < 0.01). Another study 23 focused on predicting postoperative liver failure in 47 patients undergoing major hepatectomy through mathematical models of blood circulation. The study highlighted that elevated Postoperative Portal Vein pressure (PPV) and Portocaval Gradient (PCG) values above 17.5 mmHg and 13.5 mmHg, respectively, correlated with the measured values (all, P < 0.0001; Table 2 ). These indicators were effective in predicting post-hepatectomy liver failure, accurately identifying three out of four patients who experienced this complication. Cho et al. 24 created digital twins for 50 adult female patients using facial scans and cone-beam computed tomography images to evaluate the anteroposterior position of the maxillary central incisors and forehead inclination. The analysis demonstrated significant differences in the position of the maxillary central incisors ( P = 0.04) and forehead inclination ( P = 0.02) between the two groups.

This systematic review outlines the effectiveness of digital twins in improving health-related outcomes across various diseases, including cancers, type 2 diabetes, multiple sclerosis, qi deficiency, heart failure, post-hepatectomy liver failure, and dental issues, at the population level. Distinct from prior reviews that focused on the technological dimensions of digital twins, our analysis shows the practical applications of digital twins in healthcare. The applications have been categorized into three main areas: personalized health management, precision individual therapy effects, and predicting individual risks, encompassing a total of 45 outcomes. An overall effectiveness of 80% was observed across these outcomes. This review offers valuable insights into the application of digital twins in precision health and supports the transition of digital twins from construction to population-wide implementation.

Digital twins play a crucial role in achieving precision health 25 . They serve as virtual models of human organs, tissues, cells, or microenvironments, dynamically updating based on real-time data to offer feedback for interventions on their real counterparts 26 , 27 . Digital twins can solve complex problems in personalized health management 28 , 29 and enable comprehensive, proactive, and precise healthcare 30 . In the studies reviewed, researchers implemented digital twins by creating virtual patients based on personal health data and using simulations to generate personalized recommendations and predictions. It is worth noting that while certain indicators have not experienced significant improvement in personalized health management for patients with type 2 diabetes and Qi deficiency, it does not undermine the effectiveness of digital twins. Firstly, these studies have demonstrated significant improvements in primary outcome measures. Secondly, improving health-related outcomes in chronic diseases is an ongoing, complex process heavily influenced by changes in health behaviors 31 , 32 . While digital twins can provide personalized health guidance based on individual health data, their impact on actual behaviors warrants further investigation.

The dual nature of medications, providing benefits yet potentially leading to severe clinical outcomes like morbidity or mortality, must be carefully considered. The impact of therapy is subject to various factors, including the drug attributes and the specific disease characteristics 33 . Achieving accurate medication administration remains a significant challenge for healthcare providers 34 , underscoring the need for innovative methodologies like computational precise drug delivery 35 , 36 , a example highlighted in our review of digital twins. Regarding the prediction of individual therapy effects for conditions such as cancer, multiple sclerosis, and heart failure, six studies within this review have reported partly significant improvements in patient health-related outcomes. These advancements facilitate the tailored selection and dosing of therapy, underscoring the ability of digital twins to optimize patient-specific treatment plans effectively.

Furthermore, digital twins can enhance clinical understanding and personalize disease risk prediction 37 . It enables a quantitative understanding and prediction of individuals by continuously predicting and evaluating patient data in a virtual environment 38 . In patients with multiple sclerosis, digital twins have facilitated predictions regarding the onset of disease-specific brain atrophy, allowing for early intervention strategies. Similarly, digital twins assessed the risk of liver failure after liver resection, aiding healthcare professionals in making timely decisions. Moreover, the application of digital twins in the three-dimensional analysis of patients with dental problems has demonstrated highly effective clinical significance, underscoring its potential across various medical specialties. In summary, the adoption of digital twins has significantly contributed to advancing precision health and restoring patient well-being by creating virtual patients based on personal health data and using simulations to generate personalized recommendations and predictions.

Recent studies have introduced various digital twin systems, covering areas such as hospital management 8 , remote monitoring 9 , and diagnosing and treating various conditions 39 , 40 . Nevertheless, these systems were not included in this review due to the lack of detailed descriptions at the population health level, which constrains the broader application of this emerging technology. Our analysis underscores the reported effectiveness of digital twins, providing unique opportunities for dynamic prevention and precise intervention across different diseases. Multiple research methodologies and outcome measures poses a challenge for quantitative publication detection. This systematic review employed a comprehensive retrieval strategy across various databases for screening articles on the effectiveness of digital twins, to reduce the omission of negative results. And four repeated publications were excluded based on authors, affiliation, population, and other criteria to mitigate the bias of overestimating the digital twins effect due to repeated publication.

However, there are still limitations. Firstly, the limited published research on digital twins’ application at the population level hinders the ability to perform a quantitative meta-analysis, possibly limiting our findings’ interpretability. We encourage reporting additional high-quality randomized controlled trials on the applicability of digital twins to facilitate quantitative analysis of their effectiveness in precision health at the population level. Secondly, this review assessed the effectiveness of digital twins primarily through statistical significance ( P -value or 95% confidence interval). However, there are four quasi-experimental studies did not report statistical significance. One of the limitations of this study is the use of significant changes in author self-reports as a criterion in these four quasi-experimental studies for identifying effectiveness. In clinical practice, the author’s self-reported clinical significance can also provide the effectiveness of digital twins. Thirdly, by focusing solely on studies published in Chinese and English, this review may have omitted relevant research available in other languages, potentially limiting the scope of the analyzed literature. Lastly, our review primarily emphasized reporting statistical differences between groups. Future work should incorporate more application feedback from real patients to expose digital twins to the nuances of actual patient populations.

The application of digital twins is currently limited and primarily focused on precision health for individual patients. Expanding digital twins’ application from individual to group precision health is recommended to signify a more extensive integration in healthcare settings. This expansion involves sharing real-time data and integrating medical information across diverse medical institutions within a region, signifying the development of group precision health. Investigating both personalized medical care and collective health management has significant implications for improving medical diagnosis and treatment approaches, predicting disease risks, optimizing health management strategies, and reducing societal healthcare costs 41 .

Digital twins intervention encompasses various aspects such as health management, decision-making, and prediction, among others 9 . It represents a technological and conceptual innovation in traditional population health intervention. However, the current content design of the digital twins intervention is insufficient and suggests that it should be improved by incorporating more effective content strategies tailored to the characteristics of the target population. Findings from this study indicate that interventions did not differ significantly in our study is from digital twins driven by personalized health management, which means that compared with the other two function-driven digital twins, personalized health management needs to receive more attention to enhance its effect in population-level. For example, within the sphere of chronic disease management, integrating effective behavioral change strategies into digital twins is advisable to positively influence health-related indicators, such as weight and BMI. The effectiveness of such digital behavior change strategies has been reported in previous studies 42 , 43 . The consensus among researchers on the importance of combining effective content strategies with digital intervention technologies underscores the potential for this approach to improve patient health-related outcomes significantly.