An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Microbiol Biol Educ

- v.16(1); 2015 May

Case Study Teaching Method Improves Student Performance and Perceptions of Learning Gains †

Associated data.

- Appendix 1: Example assessment questions used to assess the effectiveness of case studies at promoting learning

- Appendix 2: Student learning gains were assessed using a modified version of the SALG course evaluation tool

Following years of widespread use in business and medical education, the case study teaching method is becoming an increasingly common teaching strategy in science education. However, the current body of research provides limited evidence that the use of published case studies effectively promotes the fulfillment of specific learning objectives integral to many biology courses. This study tested the hypothesis that case studies are more effective than classroom discussions and textbook reading at promoting learning of key biological concepts, development of written and oral communication skills, and comprehension of the relevance of biological concepts to everyday life. This study also tested the hypothesis that case studies produced by the instructor of a course are more effective at promoting learning than those produced by unaffiliated instructors. Additionally, performance on quantitative learning assessments and student perceptions of learning gains were analyzed to determine whether reported perceptions of learning gains accurately reflect academic performance. The results reported here suggest that case studies, regardless of the source, are significantly more effective than other methods of content delivery at increasing performance on examination questions related to chemical bonds, osmosis and diffusion, mitosis and meiosis, and DNA structure and replication. This finding was positively correlated to increased student perceptions of learning gains associated with oral and written communication skills and the ability to recognize connections between biological concepts and other aspects of life. Based on these findings, case studies should be considered as a preferred method for teaching about a variety of concepts in science courses.

INTRODUCTION

The case study teaching method is a highly adaptable style of teaching that involves problem-based learning and promotes the development of analytical skills ( 8 ). By presenting content in the format of a narrative accompanied by questions and activities that promote group discussion and solving of complex problems, case studies facilitate development of the higher levels of Bloom’s taxonomy of cognitive learning; moving beyond recall of knowledge to analysis, evaluation, and application ( 1 , 9 ). Similarly, case studies facilitate interdisciplinary learning and can be used to highlight connections between specific academic topics and real-world societal issues and applications ( 3 , 9 ). This has been reported to increase student motivation to participate in class activities, which promotes learning and increases performance on assessments ( 7 , 16 , 19 , 23 ). For these reasons, case-based teaching has been widely used in business and medical education for many years ( 4 , 11 , 12 , 14 ). Although case studies were considered a novel method of science education just 20 years ago, the case study teaching method has gained popularity in recent years among an array of scientific disciplines such as biology, chemistry, nursing, and psychology ( 5 – 7 , 9 , 11 , 13 , 15 – 17 , 21 , 22 , 24 ).

Although there is now a substantive and growing body of literature describing how to develop and use case studies in science teaching, current research on the effectiveness of case study teaching at meeting specific learning objectives is of limited scope and depth. Studies have shown that working in groups during completion of case studies significantly improves student perceptions of learning and may increase performance on assessment questions, and that the use of clickers can increase student engagement in case study activities, particularly among non-science majors, women, and freshmen ( 7 , 21 , 22 ). Case study teaching has been shown to improve exam performance in an anatomy and physiology course, increasing the mean score across all exams given in a two-semester sequence from 66% to 73% ( 5 ). Use of case studies was also shown to improve students’ ability to synthesize complex analytical questions about the real-world issues associated with a scientific topic ( 6 ). In a high school chemistry course, it was demonstrated that the case study teaching method produces significant increases in self-reported control of learning, task value, and self-efficacy for learning and performance ( 24 ). This effect on student motivation is important because enhanced motivation for learning activities has been shown to promote student engagement and academic performance ( 19 , 24 ). Additionally, faculty from a number of institutions have reported that using case studies promotes critical thinking, learning, and participation among students, especially in terms of the ability to view an issue from multiple perspectives and to grasp the practical application of core course concepts ( 23 ).

Despite what is known about the effectiveness of case studies in science education, questions remain about the functionality of the case study teaching method at promoting specific learning objectives that are important to many undergraduate biology courses. A recent survey of teachers who use case studies found that the topics most often covered in general biology courses included genetics and heredity, cell structure, cells and energy, chemistry of life, and cell cycle and cancer, suggesting that these topics should be of particular interest in studies that examine the effectiveness of the case study teaching method ( 8 ). However, the existing body of literature lacks direct evidence that the case study method is an effective tool for teaching about this collection of important topics in biology courses. Further, the extent to which case study teaching promotes development of science communication skills and the ability to understand the connections between biological concepts and everyday life has not been examined, yet these are core learning objectives shared by a variety of science courses. Although many instructors have produced case studies for use in their own classrooms, the production of novel case studies is time-consuming and requires skills that not all instructors have perfected. It is therefore important to determine whether case studies published by instructors who are unaffiliated with a particular course can be used effectively and obviate the need for each instructor to develop new case studies for their own courses. The results reported herein indicate that teaching with case studies results in significantly higher performance on examination questions about chemical bonds, osmosis and diffusion, mitosis and meiosis, and DNA structure and replication than that achieved by class discussions and textbook reading for topics of similar complexity. Case studies also increased overall student perceptions of learning gains and perceptions of learning gains specifically related to written and oral communication skills and the ability to grasp connections between scientific topics and their real-world applications. The effectiveness of the case study teaching method at increasing academic performance was not correlated to whether the case study used was authored by the instructor of the course or by an unaffiliated instructor. These findings support increased use of published case studies in the teaching of a variety of biological concepts and learning objectives.

Student population

This study was conducted at Kingsborough Community College, which is part of the City University of New York system, located in Brooklyn, New York. Kingsborough Community College has a diverse population of approximately 19,000 undergraduate students. The student population included in this study was enrolled in the first semester of a two-semester sequence of general (introductory) biology for biology majors during the spring, winter, or summer semester of 2014. A total of 63 students completed the course during this time period; 56 students consented to the inclusion of their data in the study. Of the students included in the study, 23 (41%) were male and 33 (59%) were female; 40 (71%) were registered as college freshmen and 16 (29%) were registered as college sophomores. To normalize participant groups, the same student population pooled from three classes taught by the same instructor was used to assess both experimental and control teaching methods.

Course material

The four biological concepts assessed during this study (chemical bonds, osmosis and diffusion, mitosis and meiosis, and DNA structure and replication) were selected as topics for studying the effectiveness of case study teaching because they were the key concepts addressed by this particular course that were most likely to be taught in a number of other courses, including biology courses for both majors and nonmajors at outside institutions. At the start of this study, relevant existing case studies were freely available from the National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science (NCCSTS) to address mitosis and meiosis and DNA structure and replication, but published case studies that appropriately addressed chemical bonds and osmosis and diffusion were not available. Therefore, original case studies that addressed the latter two topics were produced as part of this study, and case studies produced by unaffiliated instructors and published by the NCCSTS were used to address the former two topics. By the conclusion of this study, all four case studies had been peer-reviewed and accepted for publication by the NCCSTS ( http://sciencecases.lib.buffalo.edu/cs/ ). Four of the remaining core topics covered in this course (macromolecules, photosynthesis, genetic inheritance, and translation) were selected as control lessons to provide control assessment data.

To minimize extraneous variation, control topics and assessments were carefully matched in complexity, format, and number with case studies, and an equal amount of class time was allocated for each case study and the corresponding control lesson. Instruction related to control lessons was delivered using minimal slide-based lectures, with emphasis on textbook reading assignments accompanied by worksheets completed by students in and out of the classroom, and small and large group discussion of key points. Completion of activities and discussion related to all case studies and control topics that were analyzed was conducted in the classroom, with the exception of the take-home portion of the osmosis and diffusion case study.

Data collection and analysis

This study was performed in accordance with a protocol approved by the Kingsborough Community College Human Research Protection Program and the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of the City University of New York (CUNY IRB reference 539938-1; KCC IRB application #: KCC 13-12-126-0138). Assessment scores were collected from regularly scheduled course examinations. For each case study, control questions were included on the same examination that were similar in number, format, point value, and difficulty level, but related to a different topic covered in the course that was of similar complexity. Complexity and difficulty of both case study and control questions were evaluated using experiential data from previous iterations of the course; the Bloom’s taxonomy designation and amount of material covered by each question, as well as the average score on similar questions achieved by students in previous iterations of the course was considered in determining appropriate controls. All assessment questions were scored using a standardized, pre-determined rubric. Student perceptions of learning gains were assessed using a modified version of the Student Assessment of Learning Gains (SALG) course evaluation tool ( http://www.salgsite.org ), distributed in hardcopy and completed anonymously during the last week of the course. Students were presented with a consent form to opt-in to having their data included in the data analysis. After the course had concluded and final course grades had been posted, data from consenting students were pooled in a database and identifying information was removed prior to analysis. Statistical analysis of data was conducted using the Kruskal-Wallis one-way analysis of variance and calculation of the R 2 coefficient of determination.

Teaching with case studies improves performance on learning assessments, independent of case study origin

To evaluate the effectiveness of the case study teaching method at promoting learning, student performance on examination questions related to material covered by case studies was compared with performance on questions that covered material addressed through classroom discussions and textbook reading. The latter questions served as control items; assessment items for each case study were compared with control items that were of similar format, difficulty, and point value ( Appendix 1 ). Each of the four case studies resulted in an increase in examination performance compared with control questions that was statistically significant, with an average difference of 18% ( Fig. 1 ). The mean score on case study-related questions was 73% for the chemical bonds case study, 79% for osmosis and diffusion, 76% for mitosis and meiosis, and 70% for DNA structure and replication ( Fig. 1 ). The mean score for non-case study-related control questions was 60%, 54%, 60%, and 52%, respectively ( Fig. 1 ). In terms of examination performance, no significant difference between case studies produced by the instructor of the course (chemical bonds and osmosis and diffusion) and those produced by unaffiliated instructors (mitosis and meiosis and DNA structure and replication) was indicated by the Kruskal-Wallis one-way analysis of variance. However, the 25% difference between the mean score on questions related to the osmosis and diffusion case study and the mean score on the paired control questions was notably higher than the 13–18% differences observed for the other case studies ( Fig. 1 ).

Case study teaching method increases student performance on examination questions. Mean score on a set of examination questions related to lessons covered by case studies (black bars) and paired control questions of similar format and difficulty about an unrelated topic (white bars). Chemical bonds, n = 54; Osmosis and diffusion, n = 54; Mitosis and meiosis, n = 51; DNA structure and replication, n = 50. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean (SEM). Asterisk indicates p < 0.05.

Case study teaching increases student perception of learning gains related to core course objectives

Student learning gains were assessed using a modified version of the SALG course evaluation tool ( Appendix 2 ). To determine whether completing case studies was more effective at increasing student perceptions of learning gains than completing textbook readings or participating in class discussions, perceptions of student learning gains for each were compared. In response to the question “Overall, how much did each of the following aspects of the class help your learning?” 82% of students responded that case studies helped a “good” or “great” amount, compared with 70% for participating in class discussions and 58% for completing textbook reading; only 4% of students responded that case studies helped a “small amount” or “provided no help,” compared with 2% for class discussions and 22% for textbook reading ( Fig. 2A ). The differences in reported learning gains derived from the use of case studies compared with class discussion and textbook readings were statistically significant, while the difference in learning gains associated with class discussion compared with textbook reading was not statistically significant by a narrow margin ( p = 0.051).

The case study teaching method increases student perceptions of learning gains. Student perceptions of learning gains are indicated by plotting responses to the question “How much did each of the following activities: (A) Help your learning overall? (B) Improve your ability to communicate your knowledge of scientific concepts in writing? (C) Improve your ability to communicate your knowledge of scientific concepts orally? (D) Help you understand the connections between scientific concepts and other aspects of your everyday life?” Reponses are represented as follows: Helped a great amount (black bars); Helped a good amount (dark gray bars); Helped a moderate amount (medium gray bars); Helped a small amount (light gray bars); Provided no help (white bars). Asterisk indicates p < 0.05.

To elucidate the effectiveness of case studies at promoting learning gains related to specific course learning objectives compared with class discussions and textbook reading, students were asked how much each of these methods of content delivery specifically helped improve skills that were integral to fulfilling three main course objectives. When students were asked how much each of the methods helped “improve your ability to communicate knowledge of scientific concepts in writing,” 81% of students responded that case studies help a “good” or “great” amount, compared with 63% for class discussions and 59% for textbook reading; only 6% of students responded that case studies helped a “small amount” or “provided no help,” compared with 8% for class discussions and 21% for textbook reading ( Fig. 2B ). When the same question was posed about the ability to communicate orally, 81% of students responded that case studies help a “good” or “great” amount, compared with 68% for class discussions and 50% for textbook reading, while the respective response rates for helped a “small amount” or “provided no help,” were 4%, 6%, and 25% ( Fig. 2C ). The differences in learning gains associated with both written and oral communication were statistically significant when completion of case studies was compared with either participation in class discussion or completion of textbook readings. Compared with textbook reading, class discussions led to a statistically significant increase in oral but not written communication skills.

Students were then asked how much each of the methods helped them “understand the connections between scientific concepts and other aspects of your everyday life.” A total of 79% of respondents declared that case studies help a “good” or “great” amount, compared with 70% for class discussions and 57% for textbook reading ( Fig. 2D ). Only 4% stated that case studies and class discussions helped a “small amount” or “provided no help,” compared with 21% for textbook reading ( Fig. 2D ). Similar to overall learning gains, the use of case studies significantly increased the ability to understand the relevance of science to everyday life compared with class discussion and textbook readings, while the difference in learning gains associated with participation in class discussion compared with textbook reading was not statistically significant ( p = 0.054).

Student perceptions of learning gains resulting from case study teaching are positively correlated to increased performance on examinations, but independent of case study author

To test the hypothesis that case studies produced specifically for this course by the instructor were more effective at promoting learning gains than topically relevant case studies published by authors not associated with this course, perceptions of learning gains were compared for each of the case studies. For both of the case studies produced by the instructor of the course, 87% of students indicated that the case study provided a “good” or “great” amount of help to their learning, and 2% indicated that the case studies provided “little” or “no” help ( Table 1 ). In comparison, an average of 85% of students indicated that the case studies produced by an unaffiliated instructor provided a “good” or “great” amount of help to their learning, and 4% indicated that the case studies provided “little” or “no” help ( Table 1 ). The instructor-produced case studies yielded both the highest and lowest percentage of students reporting the highest level of learning gains (a “great” amount), while case studies produced by unaffiliated instructors yielded intermediate values. Therefore, it can be concluded that the effectiveness of case studies at promoting learning gains is not significantly affected by whether or not the course instructor authored the case study.

Case studies positively affect student perceptions of learning gains about various biological topics.

Finally, to determine whether performance on examination questions accurately predicts student perceptions of learning gains, mean scores on examination questions related to case studies were compared with reported perceptions of learning gains for those case studies ( Fig. 3 ). The coefficient of determination (R 2 value) was 0.81, indicating a strong, but not definitive, positive correlation between perceptions of learning gains and performance on examinations, suggesting that student perception of learning gains is a valid tool for assessing the effectiveness of case studies ( Fig. 3 ). This correlation was independent of case study author.

Perception of learning gains but not author of case study is positively correlated to score on related examination questions. Percentage of students reporting that each specific case study provided “a great amount of help” to their learning was plotted against the point difference between mean score on examination questions related to that case study and mean score on paired control questions. Positive point differences indicate how much higher the mean scores on case study-related questions were than the mean scores on paired control questions. Black squares represent case studies produced by the instructor of the course; white squares represent case studies produced by unaffiliated instructors. R 2 value indicates the coefficient of determination.

The purpose of this study was to test the hypothesis that teaching with case studies produced by the instructor of a course is more effective at promoting learning gains than using case studies produced by unaffiliated instructors. This study also tested the hypothesis that the case study teaching method is more effective than class discussions and textbook reading at promoting learning gains associated with four of the most commonly taught topics in undergraduate general biology courses: chemical bonds, osmosis and diffusion, mitosis and meiosis, and DNA structure and replication. In addition to assessing content-based learning gains, development of written and oral communication skills and the ability to connect scientific topics with real-world applications was also assessed, because these skills were overarching learning objectives of this course, and classroom activities related to both case studies and control lessons were designed to provide opportunities for students to develop these skills. Finally, data were analyzed to determine whether performance on examination questions is positively correlated to student perceptions of learning gains resulting from case study teaching.

Compared with equivalent control questions about topics of similar complexity taught using class discussions and textbook readings, all four case studies produced statistically significant increases in the mean score on examination questions ( Fig. 1 ). This indicates that case studies are more effective than more commonly used, traditional methods of content delivery at promoting learning of a variety of core concepts covered in general biology courses. The average increase in score on each test item was equivalent to nearly two letter grades, which is substantial enough to elevate the average student performance on test items from the unsatisfactory/failing range to the satisfactory/passing range. The finding that there was no statistical difference between case studies in terms of performance on examination questions suggests that case studies are equally effective at promoting learning of disparate topics in biology. The observations that students did not perform significantly less well on the first case study presented (chemical bonds) compared with the other case studies and that performance on examination questions did not progressively increase with each successive case study suggests that the effectiveness of case studies is not directly related to the amount of experience students have using case studies. Furthermore, anecdotal evidence from previous semesters of this course suggests that, of the four topics addressed by cases in this study, DNA structure and function and osmosis and diffusion are the first and second most difficult for students to grasp. The lack of a statistical difference between case studies therefore suggests that the effectiveness of a case study at promoting learning gains is not directly proportional to the difficulty of the concept covered. However, the finding that use of the osmosis and diffusion case study resulted in the greatest increase in examination performance compared with control questions and also produced the highest student perceptions of learning gains is noteworthy and could be attributed to the fact that it was the only case study evaluated that included a hands-on experiment. Because the inclusion of a hands-on kinetic activity may synergistically enhance student engagement and learning and result in an even greater increase in learning gains than case studies that lack this type of activity, it is recommended that case studies that incorporate this type of activity be preferentially utilized.

Student perceptions of learning gains are strongly motivating factors for engagement in the classroom and academic performance, so it is important to assess the effect of any teaching method in this context ( 19 , 24 ). A modified version of the SALG course evaluation tool was used to assess student perceptions of learning gains because it has been previously validated as an efficacious tool ( Appendix 2 ) ( 20 ). Using the SALG tool, case study teaching was demonstrated to significantly increase student perceptions of overall learning gains compared with class discussions and textbook reading ( Fig. 2A ). Case studies were shown to be particularly useful for promoting perceived development of written and oral communication skills and for demonstrating connections between scientific topics and real-world issues and applications ( Figs. 2B–2D ). Further, student perceptions of “great” learning gains positively correlated with increased performance on examination questions, indicating that assessment of learning gains using the SALG tool is both valid and useful in this course setting ( Fig. 3 ). These findings also suggest that case study teaching could be used to increase student motivation and engagement in classroom activities and thus promote learning and performance on assessments. The finding that textbook reading yielded the lowest student perceptions of learning gains was not unexpected, since reading facilitates passive learning while the class discussions and case studies were both designed to promote active learning.

Importantly, there was no statistical difference in student performance on examinations attributed to the two case studies produced by the instructor of the course compared with the two case studies produced by unaffiliated instructors. The average difference between the two instructor-produced case studies and the two case studies published by unaffiliated instructors was only 3% in terms of both the average score on examination questions (76% compared with 73%) and the average increase in score compared with paired control items (14% compared with 17%) ( Fig. 1 ). Even when considering the inherent qualitative differences of course grades, these differences are negligible. Similarly, the effectiveness of case studies at promoting learning gains was not significantly affected by the origin of the case study, as evidenced by similar percentages of students reporting “good” and “great” learning gains regardless of whether the case study was produced by the course instructor or an unaffiliated instructor ( Table 1 ).

The observation that case studies published by unaffiliated instructors are just as effective as those produced by the instructor of a course suggests that instructors can reasonably rely on the use of pre-published case studies relevant to their class rather than investing the considerable time and effort required to produce a novel case study. Case studies covering a wide range of topics in the sciences are available from a number of sources, and many of them are free access. The National Center for Case Study Teaching in Science (NCCSTS) database ( http://sciencecases.lib.buffalo.edu/cs/ ) contains over 500 case studies that are freely available to instructors, and are accompanied by teaching notes that provide logistical advice and additional resources for implementing the case study, as well as a set of assessment questions with a password-protected answer key. Case study repositories are also maintained by BioQUEST Curriculum Consortium ( http://www.bioquest.org/icbl/cases.php ) and the Science Case Network ( http://sciencecasenet.org ); both are available for use by instructors from outside institutions.

It should be noted that all case studies used in this study were rigorously peer-reviewed and accepted for publication by the NCCSTS prior to the completion of this study ( 2 , 10 , 18 , 25 ); the conclusions of this study may not apply to case studies that were not developed in accordance with similar standards. Because case study teaching involves skills such as creative writing and management of dynamic group discussion in a way that is not commonly integrated into many other teaching methods, it is recommended that novice case study teachers seek training or guidance before writing their first case study or implementing the method. The lack of a difference observed in the use of case studies from different sources should be interpreted with some degree of caution since only two sources were represented in this study, and each by only two cases. Furthermore, in an educational setting, quantitative differences in test scores might produce meaningful qualitative differences in course grades even in the absence of a p value that is statistically significant. For example, there is a meaningful qualitative difference between test scores that result in an average grade of C− and test scores that result in an average grade of C+, even if there is no statistically significant difference between the two sets of scores.

In the future, it could be informative to confirm these findings using a larger cohort, by repeating the study at different institutions with different instructors, by evaluating different case studies, and by directly comparing the effectiveness of the case studying teaching method with additional forms of instruction, such as traditional chalkboard and slide-based lecturing, and laboratory-based activities. It may also be informative to examine whether demographic factors such as student age and gender modulate the effectiveness of the case study teaching method, and whether case studies work equally well for non-science majors taking a science course compared with those majoring in the subject. Since the topical material used in this study is often included in other classes in both high school and undergraduate education, such as cell biology, genetics, and chemistry, the conclusions of this study are directly applicable to a broad range of courses. Presently, it is recommended that the use of case studies in teaching undergraduate general biology and other science courses be expanded, especially for the teaching of capacious issues with real-world applications and in classes where development of written and oral communication skills are key objectives. The use of case studies that involve hands-on activities should be emphasized to maximize the benefit of this teaching method. Importantly, instructors can be confident in the use of pre-published case studies to promote learning, as there is no indication that the effectiveness of the case study teaching method is reliant on the production of novel, customized case studies for each course.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIALS

Acknowledgments.

This article benefitted from a President’s Faculty Innovation Grant, Kingsborough Community College. The author declares that there are no conflicts of interest.

† Supplemental materials available at http://jmbe.asm.org

- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Original research article, a qualitative analysis of teachers’ perception of classroom pedagogical accompaniment program.

- 1 Department of Educational Foundations, Universidad Católica del Maule, Talca, Chile

- 2 Faculty of Economics and Business, Universidad de Talca, Talca, Chile

- 3 Department of Languages, Universidad Católica del Maule, Talca, Chile

The need to increase educational quality has led public policymakers to create and implement strategies for improving teachers’ skills. One such strategy, adapted in Chile, is the classroom accompaniment program, which has become a case of teacher professional development. The present study primarily seeks to understand public schoolteachers’ perception on classroom pedagogical accompaniment program (CPAP), and at the same time its effectiveness. This qualitative research is a case study framed within an interpretive paradigm, in which semi-structured interviews were conducted to collect data. A content analysis was done with 4 categories and 10 subcategories of perceptions attributed to the program and its effectiveness by 13 teachers, 8 females and 5 males, belonging to four public educational establishments. The results show opposed perceptions about the existing accompaniment program. On one hand, some teachers rate it positively and consider it beneficial for them and their students, who also received adequate feedback. On the other hand, another group of teachers considered that there were no positive contributions to their work performance, with impacts including greater reticence during the in-class observation process. Thus, the study concludes that the initial orientations and instruction regarding the role of the observing teacher are fundamental for the classroom accompaniment process to be effective and that it can be a valuable tool to apply for improving teacher performance.

Introduction

Access to quality education for all children is one of the top priority issues driving much of the effort around education in Chile. However, expected learning improvements have not yet been achieved. The tendency for learning as per the National Education Quality Measurement System (Sistema de Medición de la Calidad de la Educación, SIMCE) test shows that language and math results have stagnated. Further, it was found that there was a negative gap persisting in school results between students from lower and higher socioeconomic levels ( Quaresma and Valenzuela, 2017 ; Muñoz-Chereau, 2019 ). This fact, on the one hand, presents a major national challenge to improve achievement results, and on the other hand, shows the need to review the implementation of reforms oriented toward improving education.

One of the major factors influencing public policy outcomes is teachers’ perceptions of proposed policy changes or reticence toward quality measurement systems and accountability. Furthermore, multiple studies indicate that the teacher is the key element in educational transformation and, consequently, in learning achievement ( Jackson et al., 2014 ; Ker, 2016 ; Duong et al., 2019 ; Roorda et al., 2020 ). Therefore, knowing teachers’ perceptions on the implemented policy measures is relevant for determining their impact or efficacy.

One of the programs implemented in Chile is the Pedagogical Accompaniment Program. This program seeks to provide technical and pedagogical support to teachers to help them improve the methodological practices with which they teach mathematics and language curriculum and content. However, for any program to be effective, it must recognize participants’ perceptions toward the same, given their impact on the success or failure of any intervention.

In this context, considering the aforementioned discussions, the objective of this study is to know the perceptions attributed by teachers in the Maule Region to the Classroom Pedagogical Accompaniment Program (CPAP) and its effectiveness. This is relevant considering that the efficacy of the program depends on teachers’ perceptions, and their understanding, which can guide the formulation of public policy in this area. In fact, studying the perceptions of teachers on the accompaniment program allows us to identify and highlight the key ideas that will favor a comprehensive understanding of this professional development strategy and guide initial teacher training. For this purpose, a case study methodology was used through semi-structured interviews, which were encoded and analyzed.

Background and Theoretical Groundings

Pedagogical accompaniment.

Pedagogical accompaniment is a strategy, which forms part of the professional development models centered on schools, fulfilling the challenge of breaking one of the greatest barriers in teaching: isolation and solitary work. According to Pirard et al. (2018) , this strategy is oriented toward continual teacher training to improve their teaching skills. This occurs through a process of classroom intervention aimed at leaving behind the strategies designed and implemented by experts and specialists from outside the school and instead of becoming a knowledge source, through peer experience, generating knowledge around learning and its context ( Vezub, 2011 ).

Haro (2014) indicated that pedagogical accompaniment is a strategy for collaborating with the teacher during the teaching process, principally by identifying weaknesses, lacks, and strengths observed in teaching practices and working to overcome difficulties in order to give better classes. In fact, evidences indicated that the practice of teacher accompaniment, along with others positively impacted teaching practices ( Leithwood, 2009 ; Jerez Yáñez et al., 2019 ).

In other words, pedagogical accompaniment is understood as a peer knowledge construction procedure, which can become a powerful pedagogical practice improvement tool. However, Batlle (2010) maintained that accompaniment imposed vertically from above would become a tool of destruction. On the contrary, if it is approached as a horizontal, peer-driven process where experiences are shared for mutual enrichment as a team, accompaniment becomes a tool for building ( Jerez Yáñez et al., 2019 ).

In fact, it is essential to ensure instances of teacher training, to support teachers in the use of acquired skills, to generate conditions for sharing ideas and practices, to show confidence in the work and progress of teachers, among other ideas that are reiterated by various authors ( DiGennaro Reed et al., 2018 ; Duong et al., 2019 ). This is favored by the practice and process of classroom accompaniment, where both the assessor and the teacher in charge can achieve common learning objectives of students ( Jerez Yáñez et al., 2019 ). Thus, evidence indicates that the teacher accompaniment strategy, interacting with other factors, has a positive impact on the improvement of teaching practices ( Vezub, 2011 ; Jerez Yáñez et al., 2019 ) and on student learning ( Berres Hartmann and Maraschin, 2019 ).

In the literature, there are researches, which demonstrate the impact of accompaniment programs on students and teachers, however, there are only a few studies evaluating the construction of the accompaniment programs based on the perceptions of the teachers. For example, Castro-Cuba-Sayco et al. (2019) studied the impact of the Strategic Learning Achievement Program in primary education students in Arequipa, concluding that it helped improve teachers’ professional practice and also contributed to students’ results in mathematics. In fact, they showed a high correlation between teacher competence and student achievement. Similarly, Berres Hartmann and Maraschin (2019) found that a pedagogical accompaniment program helped improve learning in children and the initial formation of pedagogy students.

It should be noted that according to Cardemil et al. (2010) the ultimate goal of intervention programs is to make educational quality a reality and that it is necessary to have classroom accompaniment involving observation followed by reflection on the events observed and seeking strategies to improve routines. Thus, observation and reflection are key elements in the accompaniment program.

Observation is used in various areas of human endeavors as a knowledge acquisition method. Classroom observation allows us to identify pedagogical practices, which contribute to student learning and aid teamwork, progressively improving relevant teaching practices. In other words, it aims to support the teaching and learning practices in the instructional process ( Eradze et al., 2019 ). It analyses the characteristics of the performance of teachers and their students in the real context in which the educational process takes place, avoiding making inferences about what actually happens in classrooms ( O’Leary, 2020 ).

On the contrary, the feedback of what has been observed is the sub process of teacher accompaniment, which considers a space for reflection and orientation with respect to what has been observed. The process of reflection is necessary for the accompaniment process to be effective for teacher training ( Rojas et al., 2019 ). The feedback process occurs when the results of the observation are shared, analyzed, and understood jointly between the teacher and the observer. Leithwood (2009) says that positive and constant feedback is one of the leadership actions with the greatest positive impact on teacher performance. Its usefulness comes from allowing teachers to identify their errors and successes, reorienting their practices and constituting a learning source for them ( Haro, 2014 ). Hence, the observation and feedback processes in the analysis of teachers’ perceptions of the classroom accompaniment program were considered to respond to the following research question of the study.

What are the schoolteachers’ perceptions on classroom pedagogical accompaniment program (CPAP) and its effectiveness?

Materials and Methods

The methodological design focuses on the qualitative interpretative paradigm, which allows the researchers to investigate social phenomena in the natural environment in which they occur, giving preponderance to the subjective aspects of human behavior ( Mihas, 2019 ). It was considered the most appropriate approach because it properly fulfils the coverage and comprehension of the studied phenomenon ( Alase, 2017 ). According to Arellano et al. (2018) , “it allows us to approach our everyday life and to understand, describe and sometimes explain ordinary phenomena from within.” The incorporation of this approach in the research allows us to know, describe and interpret, from the participants’ (teachers) point of view, the effectiveness of the program. Specifically, the design strategy known as a case study is used, which allows the selection of real scenarios, which constitute sources of information ( Yin, 2012 ; Mihas, 2019 ). This methodological decision makes it possible to highlight the perceptions of teachers on the Classroom Accompaniment Program.

Context of the Study

The teaching profession is currently recognized as being done and consolidated collaboratively; therefore, multiple pedagogical accompaniment programs have been implemented internationally ( Vezub, 2011 ; Roorda et al., 2020 ). In Chile, important efforts have also been made to improve teaching practices and general educational quality ( Escribano et al., 2020 ). In fact, education policymakers have come up with diverse strategies to improve educational quality and teacher performance. Among these, ideas such as the “National Induction and Mentoring System,” the “Teaching Teachers Network,” the “Shared Support Plan,” and “Classroom Advisory Programs” stand out.

The current study seeks to know the perceptions and the utility of the CPAP of the schoolteachers and the best way is to carry out a research listening to their voices for the improvement of teaching and learning. This further would provide information to the policy makers for taking policy decisions related to the educational quality.

In this context, in the Maule Region (Chile), through the support of a technical educational advisor, an implementation of the Classroom Accompaniment Program was carried out in 23 public schools for 1 year. This intervention consisted of supporting teachers in various public education establishments in the Maule Region, through this teacher accompaniment strategy. Specifically, this consisted in;

a) language and math classroom advisory, 90 min weekly for each teacher per class, throughout the year;

b) methodology course in language and didactics of mathematics through workshops of 2 h per month for each subject, throughout the school year;

c) delivery of teacher material: planners (annual-semester-class by class-unit tests-class guide), language, math, and delivery of student material: learning guides per class (language and math) and unit tests.

Participants

The Classroom Accompaniment Program was implemented in 23 public schools, of which four public schools were selected due to the diversity of their educational proposal. Three schools were from urban setup and one from rural area, wherein one from urban setup was exclusively a primary school, and the other three establishments were from both primary and secondary level. Each selected establishment responded to different educational and sociocultural needs. Within said establishments, the teachers interviewed were selected intentionally considering homogeneity and heterogeneity criteria of educational level and geographical locations. Two teachers from the rural setup, and 11 teachers from the urban schools were selected. Out of 11 teachers, 8 teachers were from two schools and 3 from one. Information was compiled on these 13 teachers, 8 females and 5 males, belonging to four public educational establishments. Each establishment represented a particular educational Project, manifesting the diverse reality of public education. The research technique applied was semi-structured interviews. This methodological decision makes it possible to investigate teachers’ perception of teaching, and its interpretation. Thus, it permitted learning about the study subject, the phenomenon under study, and about the concrete case in question ( Yin, 2012 ).

In the semi-structured guided interviews, four dimensions were considered: perception of the program, the use of the program material, the impact on student learning achievement, and the opinion on the contribution of the Program to their own work. The interview was useful for obtaining information on how teachers reconstruct and represent the classroom accompaniment experience. In other words, the interview technique provided deeper access to teachers’ own words and their perceptions regarding the phenomenon under study. Furthermore, through this technique, the interviewer had the possibility of clarifying doubts and focusing on the subject, intending to go deeper into the phenomenon.

It is also important to highlight that there was a variation over time in terms of observation/co-teaching. In a survey, 92% of the teachers who started the program participated actively in the observation and co-teaching process over the time period of the program. There was no formal negotiation between the observer and the co-teachers in the design of the program. However, this negotiation occurred spontaneously through a horizontal dialogue among the participants, which included betterment agreements to achieve quality learning of the accompanied teachers and students correspondingly.

Ethical Considerations

The study followed ethical protocols and was approved by the Ethics Committees both from Universidad Católica del Maule and Universidad de Talca. Researchers personally informed the teachers selected for this study and duly signed their consent form. The validation process of the applied instrument was also carried out through expert judgment.

Data Analysis

Data treatment was carried out through the content analysis technique, which consists of reducing information by means of interview encoding to organize and group contents related to one theme ( Krippendorff, 2018 ; Mihas, 2019 ). Systematization was carried out through the construction of integrating matrices of categories and subcategories. This process allowed the ordering of the significant segments that make up the information in the narratives to show the results as they were experienced and explained by the social actors. Initially, the analysis was done according to each source, taking into account the particularity of the guided interview, the informant, and the time at which the data was collected. The interview was carried out in the Spanish language, and the narratives were literally translated into English, to maintain the originality of the content. Data were transcribed and was grouped into categories and subcategories allowing for coding.

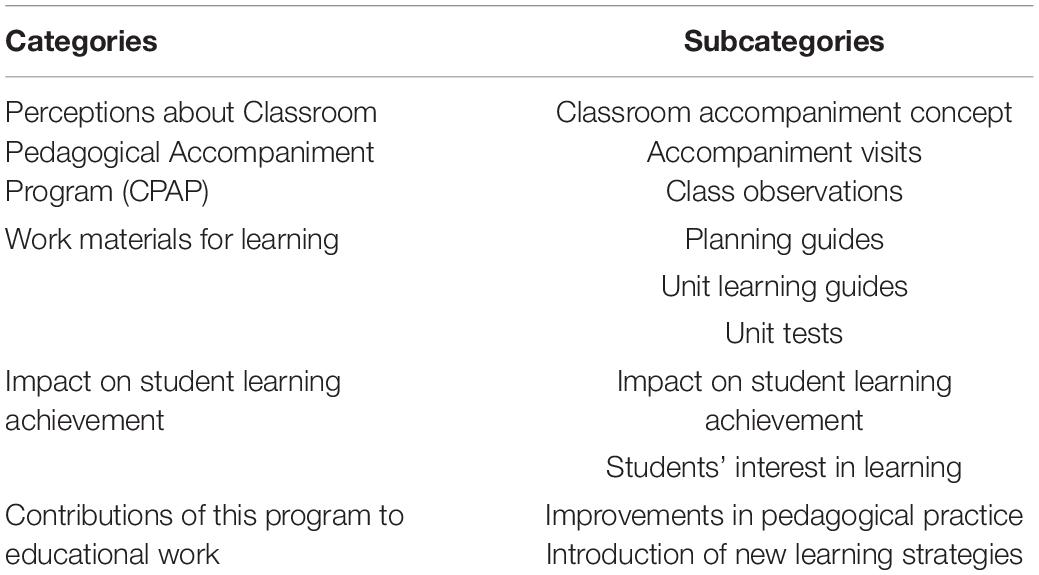

Subsequently, a systematic, rigorous, and exhaustive process was followed to reduce the data obtained and the judgment of the actors in order to arrive at a reasonable number of units of analysis that would allow them to be studied with precision and clarity ( Male, 2016 ; Mihas, 2019 ). Specifically, four categories were outlined to develop data analysis, focusing on the principal themes set out in the study: perception of the pedagogical accompaniment program, working materials for learning, impact on student learning achievement, and contribution of the program to their educational work ( Table 1 ). Each category is related to a series of subcategories that allow for a coherent link between the contributions from interviewees, literature review, and research objectives.

Table 1. Thematic analysis of categories and subcategories.

Data analysis allowed identifying relevant aspects of the intervention under study, and thus get closer to the perceptions that the teachers had of CPAP. This section is structured around different assessments of teachers regarding the four categories of analysis as identified in the previous section: perceptions regarding the CPAP, contributions of working materials for learning, impact on student learning achievement, and CPAP’s contribution to educational work. The above-mentioned is in line with the research question raised in the study and in coherence with the objective that seek to understand the perceptions attributed by public schoolteachers of the classroom accompaniment program and its effectiveness.

Classroom Pedagogical Accompaniment Program Perception

Teachers value the process as an instance of support for pedagogical work, to the extent, it provides guidance for improvement on part of the observer. In most narratives, the observer was present in the classroom, but in different roles. The first one was a more passive role where the observer avoided interrupting the development of the class and in the second one, the observer was active, who interacted with both, the students and the teacher, that is to say, he or she developed more of a co-teaching role. This affects the perception of the program.

“This person observed a couple of classes, and then started participating in them–participation in the sense of accompanying the teacher wherever improvement or changes could be carried out in class, as perceived by her.” (Math Teacher, School 2)

“I do not know if everyone was the same, but at least the person I got. I cannot remember her name. It was just another colleague who helped me. Later, during the feedback, following were her comments on my teaching “look, this is good, we can improve this other thing”—yeah, good, pretty good.” (Language Teacher 1, School 1)

It should be noted that the majority of teachers interviewed positively evaluated the classroom observation process, to the extent that the accompanying teacher collaborated in the teaching process as another teacher in the classroom. This could be considered as a confusion between the accompaniment strategy and an assistantship or co-teaching strategy.

“The other person participated more in basically accompanying the kids. She went around seeing if the kid was working, showed a positive attitude, pretty cheerful. Some things caught her attention, and she mentioned them, but finally later on she also told me all the good and bad about my class.” (Language Teacher 2, School 1)

“For me it was not accompaniment, it was supervising. I saw it like supervision, from the perception she had of my performance with the students… well, I did not see it as someone accompanying, because for me accompanying, accompaniment is also, it’s interacting with students, right? And intervening.” (Math Teacher, School 4)

Teachers recognized and valued the feedback process, emphasizing the importance of this feedback being provided in a timely and rigorous manner. In various narratives, teachers mentioned participating in feedback, showing how CPAP fulfilled the stages corresponding to the accompaniment process. However, in spite of this, their narratives showed animosity toward the action of the observer during the observation process. For instance:

“She came several times. Most times she was observing, she was supposed to be observing and after we finished the class she gave some instructions-let’s say some indications of what needed improvement, or the way the content should be presented.” (Math Teacher 2, School 1)

On the other hand, regarding the importance of the feedback process, teachers reiterated that the pedagogical accompaniment process fails to the extent that the feedback stage is ineffective or does not materialize. e.g.,

“There was no feedback, none, so when there’s no feedback, there’s nothing. I mean for me, I cannot say it was significant.” (Language Teacher 1, School 2)

“It was a great idea, a relief, I mean, a lesser load for us.” (Math Teacher 1, School 4)

They also emphasized that the intervention was conceived as a process of support for teaching as seen in the above comment. This understanding does not mean increasing the workload, but precisely the opposite.

Work Materials for Learning

The materials provided during the program were intended to be a tool for the development of the learning session, the context in which the reflective dialogue between peers takes place. In the case of the present study, the focus is centered on the interviewees’ views on the planning guides for the educational process. The opinions of the teachers are different with respect to the perception of the program. Some positively valued the delivery of abundant didactic material and the orientations from teachers who intervened in the accompaniment process. e.g.,

“I recall they did classes too, a demo class with all the parts of a class, so that generated lots of feedback. Professionally it was good because having another teacher from the same specialty in the classroom where you can share a learning experience is what helps you grow.” (Math Teacher 2, School 4)

“We teachers complain or complained that we did not have time to prepare material and those things, so I think from that point of view it helped.” (Language Teacher 2, School 2)

“The good thing is that the whole thing was put together, so it favored planning (…), so they went to the objective we needed, and then we just had to adjust a few things and not have to put together this entire plan.” (Language Teacher 2, School 1)

However, not all teachers used the material given by CPAP. This occurred for different reasons, either because they considered the materials not suitable for their students or because they did not fit in with their previous planning, e.g.,

“The guides, like I was saying, I used them, some of them. The folders they gave, some of us worked with them.” (Math Teacher 2, School 3)

“Let’s see, I used the ones I thought were pertinent for using…” (Language Teacher, School 3)

However, in the narratives a negative perception was frequently mentioned about the teaching materials that were given, maintaining that they were given to teachers at an inappropriate time, causing inconsistency with the material from the national curriculum or the traditional content sequence previously used by the teacher. As the following narratives indicate:

“The guides did not come in to fit the plan, so there was a lot of irregularity in how the guides and the tests are, or were ……I could not use them because I’m more structured with my classes, so what happened was, they would have the drama text up in the first unit and I did it in the last unit, so it did not come in order.” (Language Teacher 1, School 1)

In the same line, teachers highlighted the importance of contextualizing learning resources, insisting that each reality is diametrically distinct from the other and that therefore planning and supplies must respond to each reality. Focusing on this, the teachers insisted that the plans provided needed improvement, as they were standardized resources, which paid no attention to their students’ interests and learning styles. In this regard, some narratives had details such as:

“The way they’d planned and sent out these guides did not work in this reality, in this context … the students are used to their learning pace, and apart from that pace with these kinds of students you’ve got to constantly reinforce contents, something you did not see in the plans or guides.” (Math Teacher, School 2)

Furthermore, some teachers took on responsibility for the material provided, carrying out relevant contextual curricular adjustments and granting it the singularity, which would give significance and closeness to the application of the material with the students.

“I adapted, adjusted and changed it. It came in little notebooks, so each kid got one and all the semester’s guides went inside there. So before planning each class, I analyzed the plan, adapted it, and put in something really similar.” (Math Teacher 2, School 1)

From the above narration, it could be inferred that this type of attitude required time and inclination to prepare for the class.

Impact on Student Learning Achievement

Pedagogical accompaniment aims to improve student learning through optimization of teaching practice performance in classrooms. Teachers also find further implications. For instance, some indicate there was an advantage for students:

“Yes, yes, they did it, obviously the kids learned the content…” (Math Teacher 2, School 1)

“Achievement is always limited because there are some elements here that are part of student disinterest, and different factors that, that generate…, an effective and enthusiastic learning from the students.” (Math Teacher 1, School 1)

Meanwhile, other teachers move away from the premise suggesting that the accompaniment implementation lacks evidence of learning (e.g., SIMCE national quality test results) and also shows a negative perception of the implementation of the program. For instance:

“I still do not know what the impact was because they have not given any information about it, so up to now I do not know what the impact on the students was.” (Math Teacher 1, School 4)

“I think the kids did not learn with it, what they need is something fun and didactic, and there was not anything like that.” (Language Teacher, School 1)

Teachers consider learning to be a complex process involving multiple factors. Therefore, it is risky to relate this strategy to the learning achievement, even more so when, according to the teachers there was no evaluation of the program. Thus, they were unable to see the effect in the follow-up tests on student learning, as this narration illustrates:

“Achievement is always limited, because there are elements here from student disinterest, and from different factors which, which generate an, an ineffective and unenthusiastic learning from students.” (Math Teacher 1, School 1)

Teachers insist that the principal factor influencing learning achievement is teacher labor, and that they are responsible for the teaching-learning process.

“No, because it turns out that we brought the workshops, we brought the classes, we brought them in ready, they were planned by us.” (Language Teacher, School 3)

Some teachers were more radical when they indicated that the implementation of this program even impeded the student learning process.

“There was not any significant impact, because that year on the SIMCE, the kids did badly.” (Language Teacher 2, School 2)

As seen in the above narration, the teachers also emphasized the need for other strategy types involving motivational aspects synchronized with students’ interests.

Program Contribution to Educational Work

Regarding teachers’ vision about the contribution of the accompaniment program to improving their practice, it can be said that teachers were not indifferent. Some interviewees considered that intervention should improve various aspects to achieve positive impacts on pedagogical practice and student learning, while another group focused on relevant and significant aspects supporting their pedagogical work.

Specifically, some teachers had very critical impressions when they said that intervention fell short of expectations, basing their opinions on various reasons. The most reiterative arguments mentioned the lack of frequency of the accompanying teacher, the way they fulfilled an observation/supervision role, the insufficient or no feedback, bad coordination or non-fulfillment of CPAP development, and unfortunate attitudes or opinions on the part of these professionals, among various other opinions.

“The guides, yes, we could cut and paste, and do something, and at first that helped, but then later during classroom accompaniment we did not see any real contribution. Because, of course, the teacher’s in the room, observing…but there was not a follow up, like they do now, when they go into the classroom, there’s a chat, there’s a proposal, you want to improve.” (Math Teacher 3, School 4)

“No real contribution, it was not up to date, the teachers did not know about working in at-risk schools.” (Math Teacher 2, School 4)

“For me it did not help because I still had to do my plans.” (Math Teacher 1, School 1)

The above mentioned narratives make up a group of assumptions, which allow us to assume that implementation of the strategy evidently lacked rigor, or that the teacher union is resistant to change and/or criticism, which goes along with the accompaniment process. For example, this could be due to the lack of familiarity with the classroom accompaniment process, as shown by the uncomfortable attitude from the teacher and even the students with the mere presence of someone external within the classroom.

“Students were uncomfortable with her presence, because since they didn’t know her or why she came, the kids did not trust her and were uncomfortable with her presence.” (Math Teacher 1, School 1)

Some other narratives value the public policy initiative, describing it as a positive intervention and offering important suggestions about implementing future projects involving classroom intervention. In fact, some narratives highlight the efficacy of the program and the shared vision of various teachers regarding its contributions, such as the following:

“A kind of discipline support, as far as confirming your knowledge, and training for new strategies, introducing new instruments, just general didactics.” (Language Teacher 1, School 1)

“I think the essence of the program’s a great idea, there should be more programs, but with the rigor you need to enter a classroom.” (Math Teacher, School 3)

“It was an accompaniment. The general perception of CPAP was that it was positive, both for the didactic material and for the teacher interviews guiding our practice. The trainings were related with that type of classroom support too.” (Language Teacher, School 3)

“It was an accompaniment, the general perception of the program was that it was positive.” (Math Teacher, School 2)

“Since this accompaniment was for primary school, she went with us too. And this teacher showed us, gave us some tools, more than anything, all related with reading comprehension.” (Language Teacher 2, School 2)

Some participants thought of pedagogical accompaniment as an instrument allowing educators to be attentive to methodological changes arising in the professional development process. Thus, this group of teachers considered it to be an orderly, continuous process to improve teacher performance in classrooms to positively influence students’ learning process.

As previously explained, pedagogical accompaniment is a strategy for collaborating with the teacher in the teaching process, principally identifying weaknesses, lacks, and strengths observed in pedagogical practices and working to overcome difficulties to conduct better classes ( Haro, 2014 ). However, the current study results show that both the participating and accompanying teachers must have clarity about their roles, especially to carry out properly the classroom observation procedure and feedback to achieve the expected results for accompaniment. It was found that the perceptions of the teachers changes according to the role played by the accompanying teacher, with participation being well-evaluated and a negative evaluation when there was little feedback. This can be explained by the type of relationship existing between the teacher and the accompanier, as indicated by Jerez Yáñez et al. (2019) , who mention, if there is a horizontal relationship based on trust, respect, and quality, it facilitates the process of cooperation between the teacher and the assessor for the achievement of educational objectives.

In this sense, the teachers understand the CPAP process as a substantial support for their pedagogical work. This situation gives rise to guidelines for improvement on the part of the observer. However, in general, the interviewees’ narratives indicated little familiarity with the practice of classroom accompaniment, principally with classroom observation, a fearful and critical attitude regarding the observers’ actions, revealing tension and reluctance to expose their class to a third party. In this regard, Hamilton and O’Dwyer (2018) indicate that the assumptions and perceptions between teachers condition the collaboration between them. Thus, negative impacts from the program could be due to the teachers not desiring to receive feedback, which could lead to the failure of the intervention. This has been observed in other studies such as Rodríguez et al. (2016) , who found that problems with implementing accompaniment programs, such as the accompanying teachers’ profiles, negatively affected their effectiveness.

Perception of CPAP is noted to be positive when there is feedback. This is because the information received by teachers allows them to identify errors and successes, thereby reorienting their practice and constituting a learning source for them, which was perceived positively by the participating teachers. Furthermore, it reflects that teachers value peer contributions ( Miquel and Duran, 2017 ).

On the other hand, some teachers positively appraised the classroom observation process to the extent that the observer collaborated in the teaching process as an additional classroom teacher, confusing the accompaniment strategy with assistantship or co-teaching, or, in the cases where they received effective feedback, which supported teaching works. In this regard, Vezub (2011) indicates that the better the dialogue, in a climate of horizontality, interaction, personal disposition, and commitment, the greater the impact of this type of program. In fact, in some cases, the teachers’ perception of the accompaniment program is based on the domestic and affective bond formed with the professional “who accompanies,” showing a positive attitude toward the intervention when there is a liking for the observers’ actions. In other words, the greater the teachers’ willingness to be accompanied, the better their perception of the Program.

Teachers’ attitudes toward external intervention are also related to the dynamics of the educational institution, since the presence of a group of teachers who are interested in and open to this type of practice can positively influence their willingness to participate in the strategy and, therefore, their perceptions of it. It also occurs that when no culture of continuous learning is present, many obstacles are visualized for implementing accompaniment strategies among teachers, precipitating negative attitudes toward change.

Additionally, perceptions about low contributions from the program to students show that teachers expect short-term and instant results from public policies, even knowing that the effects of classroom accompaniment programs can be seen in students over the medium and long run ( Rodríguez et al., 2016 ; Berres Hartmann and Maraschin, 2019 ). This could be explained by the fact that the accountability system exerting pressure on teachers and may impact the vision of the education process ( Elacqua et al., 2016 ).

The preceding forms an array of presumptions, which allows us to assume that, on the one hand, the implementation of the strategy lacked the necessary rigor, or rather that it was necessary to work on the teachers’ disposition since they were reluctant to participate in this type of intervention with the openness that the accompaniment process needs. Furthermore, the results show the importance of adapting classroom accompaniment strategies to context. For instance, plans and inputs or materials should respond to the reality of the educational establishments, especially for those with lower learning. Thus, if an accompaniment program is implemented, it should not be standardized but adapted to different types of schools.

Finally, as a summary taken from the above-mentioned discussions, it can be stated that the CPAP is an effective tool for enriching the pedagogical work, which influences the learning process of the students. In agreement with the results obtained in the study, it can be highlighted that the accompaniment program of the teachers reveals three main steps for its successful implementation. The first being the mutual agreement between the two actors on the class-organization before its start to carry out the accompaniment process in the pedagogical program. The second being the observation of the class for the execution and development of the accompaniment program as agreed in the first step. Finally, the pedagogical dialogue between the actors that allows to the betterment of the teaching learning process based on the feedback and outcomes of CPAP. The later allows taking future pedagogical decisions in an optimal way.

The perceptions communicated by the interviewed teachers regarding the classroom accompaniment program are diverse, with the predominant idea being that classroom accompaniment is a useful strategy when implemented with the rigor needed in any intervention undertaken in the sensitive teaching-learning process. They also said that both parties; main teacher and the accompanier, need to have a shared vision of the program.

In the same way, teachers showed multiple visions about the initiation of the classroom accompaniment program and its effects. Many of the interviewees positively appraised the classroom observation process to the extent that the accompanying teacher collaborated in the teaching process as another teacher in the classroom. This represents a misconception of the strategy, confusing pedagogical accompaniment with an assistantship or co-teaching, which distorts perceptions of the process and its objectives. Thus, initial orientation and instruction about the role of the observing teacher are a priority for classroom accompaniment process effectiveness.

Regarding teachers’ vision about the contribution of the accompaniment program to improving their practice, the results indicate that there are diverse perceptions. One group of interviewees considered that the intervention needed to improve various aspects to positively impact in pedagogical practice. Another group highlighted relevant and significant aspects of support for their pedagogical work.

Regarding the use of material, the teachers’ critiques focused on the rigor of their development, highlighting the importance of learning resource contextualization. However, some teachers took on some responsibility regarding the material provided, carrying out the necessary curricular adaptations for their context. They also positively valued the support for reducing their workload by having class material available.

Regarding the impact of classroom accompaniment on student learning, the interviewed teachers highlighted that learning is a complex process involving multiple factors, emphasizing that the principal factor influencing learning achievement is teachers’ labor. They were primarily responsible for the teaching-learning process.

In general, the teachers who participated in this study considered the classroom accompaniment program to be a valuable initiative toward improving teaching. CPAP, as shared by the teachers, is expected to be implemented more rigorously and with attention to the educational context where it takes place. The teachers valued the process to the degree that it supplied tools for improving pedagogical practice, thereby affecting student learning. Therefore, it is concluded that this type of program can be carried out by considering the selection process of classroom observer, informing all actors of the process to reduce reluctance, providing adequate guidance on the actors’ roles, and adapting the contents of the program to the specific reality of the schools. That is to say, there could not be a standardized solution for peculiar realities.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Ethics Committee from Universidad Católica del Maule and Universidad de Talca. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

This research was supported by the Chilean National Agency for Research and Development (ANID) under Fondecyt Regular number 1170369 of the year 2017.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Alase, A. (2017). The interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA): a guide to a good qualitative research approach. Int. J. Educ. Lit. Stud. 5, 9–19. doi: 10.7575/aiac.ijels.v.5n.2p.9

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Arellano, R., Costa, E., and Moreira Ribeiro, J. (2018). Conocimiento y contextos interculturales: enfoques cualitativos. Rev. Forum Identidades 27, 201–212.

Google Scholar

Batlle, F. (2010). Acompañamiento docente como herramienta de construcción. Rev. Electrón. Hum. Educ. Comun. Soc. 5, 102–110.

PubMed Abstract | Google Scholar

Berres Hartmann, A. L., and Maraschin, M. S. (2019). Programa de Apoio Pedagógico: contribuições para a aprendizagem matemática de alunos do CTISM/UFSM e para a formação inicial de professores. TANGRAM Rev. Educ. Mat. 2, 96–105. doi: 10.30612/tangram.v2i4.9667

Cardemil, C., Maureira, F., Zuleta, J., and Hurtado, C. U. (2010). Modalidades de Acompañamiento y Apoyo Pedagógico al Aula. Santiago: CIDE-UA HurtBowado.

Castro-Cuba-Sayco, S. E., Espinoza-Suarez, S. M., Bejarano-Meza, M. E., Martinez-Puma, E., Ramos-Quispe, T., and García-Holgado, A. (2019). “The impact of the strategic learning achievement program in primary education students in Arequipa,” in Proceedings of the CEUR Workshop , Aachen.

DiGennaro Reed, F. D., Blackman, A. L., Erath, T. G., Brand, D., and Novak, M. D. (2018). Guidelines for using behavioral skills training to provide teacher support. Teach. Except. Child. 50, 373–380. doi: 10.1177/0040059918777241

Duong, M. T., Pullmann, M. D., Buntain-Ricklefs, J., Lee, K., Benjamin, K. S., Nguyen, L., et al. (2019). Brief teacher training improves student behavior and student-teacher relationships in middle school. Sch. Psychol. 34, 212–221. doi: 10.1037/spq0000296

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Elacqua, G., Martínez, M., Santos, H., and Urbina, D. (2016). Short-run effects of accountability pressures on teacher policies and practices in the voucher system in Santiago, Chile. Sch. Effect. Sch. Improv. 27, 385–405. doi: 10.1080/09243453.2015.1086383

Eradze, M., Rodríguez-Triana, M. J., and Laanpere, M. (2019). A conversation between learning design and classroom observations: a systematic literature review. Educ. Sci. 9:91. doi: 10.3390/educsci9020091