- Submit Content

- Business And Management

- Social Anthropology

- World Religions

- Biology 2016

- Design Technology

- Environmental Systems And Societies

- Sports Exercise And Health Science

- Mathematics Studies

- Mathematics SL

- Mathematics HL

- Computer Science

- Visual Arts

- Theory Of Knowledge

- Extended Essay

- Creativity Activity Service

- Video guides

- External links

The biological level of analysis

- General learning outcomes

- GLO1 : Outline principles that define...

- GLO2 : Explain how principles that de...

- GLO3 : Discuss how and why particular...

- GLO4 : Discuss ethical considerations...

- Physiology and Behaviour

- PB1 : Explain one study related to l...

- PB2 : Using one or more examples, ex...

- PB3 : Using one or more examples, ex...

- PB4 : Discuss two effects of the env...

- PB5 : Examine one interaction betwee...

- PB6 : Discuss the use of brain imagi...

- Genetics and Behaviour

- GB1 : With reference to relevant to ...

- GB2 : Examine one evolutionary expla...

- GB3 : Discuss ethical considerations...

The cognitive level of analysis

- Cognitive Processes

- CP1 : Evaluate schema theory with re...

- CP2 : Evaluate two models or theorie...

- CP3 : Explain how biological factors...

- CP4 : Discuss how social or cultural...

- CP5 : With reference to relevant res...

- CP6 : Discuss the use of technology ...

- Cognition and Emotion

- CE1 : To what extent do cognitive an...

- CE2 : Evaluate one theory of how emo...

The sociocultural level of analysis

- Sociocultural cognition

- SC1 : Describe the role of situation...

- SC2 : Discuss two errors in attribut...

- SC3 : Evaluate social identity theor...

- SC4 : Explain the formation of stere...

- Social Norms

- SN1 : Explain social learning theory...

- SN2 : Discuss the use of compliance ...

- SN3 : Evaluate research on conformit...

Evaluate schema theory with reference to research studies.

Introduction.

- Define schema

- Schemas are cognitive structures that organise knowledge stored in our memory.

- They are mental representations of categories (from our knowledge, beliefs and expectations) about particular aspects of the world such as people, objects, events, and situations.

- Expand on schema

- Knowledge that is stored in our memory is organized as a set of schemas (or knowledge structures), which represent the general knowledge about the world, people, events, objects, actions and situations that has been acquired from past experiences.

- Types of schemas:

- Scripts provide information about the sequence of events that occur in particular contexts (e.g. going to a restaurant, visiting the dentist, attending class).s

- Self-schemas organise information we have about ourselves (information stored in our memory about our strengths and weaknesses and how we feel about them).

- Social schemas (e.g. stereotypes) – represent information about groups of people (e.g. Americans, Egyptians, women, accountants, etc.).

- Define schema theory

- Cognitive theory of processing and organizing information.

- Schema theory states that “as active processors of information, humans integrate new information with existing, stored information.”

- Expand on schema theory Effects

- Existing knowledge stored in our memory (what we already know) and organized in the form of schemas will affect information processing and behaviour in specific settings.

- E.g. Information we already know affects the way we interpret new information and events and how we store it in our memory.

- It is not possible to see how knowledge is processed and stored in the brain, but the concept of schema theory helps psychologists understand and discuss what cannot be seen.

- Schema theory can describe how specific knowledge is organised and stored in memory so that it can be retrieved.

- State what you are doing in the essay

- Schema theory will be evaluated, making an appraisal by weighing up strengths and limitations with some reference to studies on the effect of schema on memory.

- Schema theory provides the theoretical basis for the studies reported below.

Supporting Studies

- Bartlett – “War of the Ghosts” (1932)

- Anderson & Pichert (1978)

- Brewer & Treyens – “picnic basket” (1981)

- French & Richards (1933)

*Choose three studies from the above studies in the evaluation of schema theory Supporting Study 1: Bartlett (1932) – “War of the Ghost” Introduce Study/Signpost:

- A significant researcher into schemas, Bartlett (1932) introduced the idea of schemas in his study entitled “The War of the Ghost.”

- Bartlett aimed to determine how social and cultural factors influence schemas and hence can lead to memory distortions.

- Participants used were of an English background.

- Were asked to read “The War of the Ghosts” – a Native American folk tale.

- Tested their memory of the story using serial reproduction and repeated reproduction, where they were asked to recall it six or seven times over various retention intervals.

- Serial reproduction: the first participant reading the story reproduces it on paper, which is then read by a second participant who reproduces the first participant’s reproduction, and so on until it is reproduced by six or seven different participants.

- Repeated reproduction: the same participant reproduces the story six or seven times from their own previous reproductions. Their reproductions occur between time intervals from 15 minutes to as long as several years.

Results:

- Both methods lead to similar results.

- As the number of reproductions increased, the story became shorter and there were more changes to the story.

- For example, ‘hunting seals’ changed into ‘fishing’ and ‘canoes’ became ‘boats’.

- These changes show the alteration of culturally unfamiliar things into what the English participants were culturally familiar with,

- This makes the story more understandable according to the participants’ experiences and cultural background (schemas).

- He found that recalled stories were distorted and altered in various ways making it more conventional and acceptable to their own cultural perspective (rationalization).

Conclusion:

- Memory is very inaccurate

- It is always subject to reconstruction based on pre-existing schemas

- Bartlett’s study helped to explain through the understanding of schemas when people remember stories, they typically omit (”leave out”) some details, and introduce rationalisations and distortions, because they reconstruct the story so as to make more sense in terms of their knowledge, the culture in which they were brought up in and experiences in the form of schemas.

Evaluation:

- Limitations:

- Bartlett did not explicitly ask participants to be as accurate as possible in their reproduction

- Experiment was not very controlled

- instructions were not standardised (specific)

- disregard for environmental setting of experiment

- Bartlett's study shows how schema theory is useful for understand how people categorise information, interpret stories, and make inferences.

- It also contributes to understanding of cognitive distortions in memory.

Supporting Study 2: Anderson and Pichert (1978) Introduce Study/Signpost:

- Further support for the influence of schemas of memory on cognition memory at encoding point was reported by Anderson and Pichert (1978).

- To investigate if schema processing influences encoding and retrieval.

- Half the participants were given the schema of a burglar and the other half was given the schema of a potential house-buyer.

- Participants then heard a story which was based on 72 points, previously rated by a group of people based on their importance to a potential house-buyer (leaky roof, damp basement) or a burglar (10speed bike, colour TV).

- Participants performed a distraction task for 12 minutes, before recall was tested.

- After another 5 minute delay, half of the participants were given the switched schema. Participants with burglar schema were given house-buyer schema and vice versa.

- The other half of the participants kept the same schema.

- All participants’ recalls were tested again.

- Shorter Method:

- Participants read a story from the perspective of either a burglar or potential home buyer. After they had recalled as much as they could of the story from the perspective they had been given, they were shifted to the alternative perspective (schema) and were asked to recall the story again.

- Participants who changed schema recalled 7% more points on the second recall test than the first.

- There was also a 10% increase in the recall of points directly linked to the new schema.

- The group who kept the same schema did not recall as many ideas in the second testing.

- Research also showed that people encoded different information which was irrelevant to their prevailing schema (those who had buyer schema at encoding were able to recall burglar information when the schema was changed, and vice versa).

- This shows that our schemas of “knowledge,” etc. are not always correct, because of external influences.

- Summary: On the second recall, participants recalled more information that was important only to the second perspective or schema than they had done on the first recall.

Conclusion:

- Schema processing has an influence at the encoding and retrieval stage, as new schema influenced recall at the retrieval stage.

- Strengths

- Controlled laboratory experiment allowed researchers to determine a cause-effect relationship on how schemas affect different memory processes.

- Limitations

- Lacks ecological validity

- Laboratory setting

- Unrealistic task, which does not reflect something that the general population would do

- This study provides evidence to support schema theory affecting the cognitive process of memory.

- Strength of schema theorythere is research evidence to support it.

Supporting Study 3: Brewer and Treyens (1981) “picnic basket” Introduce Study/Signpost:

- Another study demonstrating schema theory is by Brewer and Treyens (1981).

- To see whether a stereotypical schema of an office would affect memory (recall) of an office.

- Participants were taken into a university student office and left for 35 seconds before being taken to another room.

- They were asked to write down as much as they could remember from the office.

Results:

- Participants recalled things of a “typical office” according to their schema.

- They did not recall the wine and picnic basket that were in the office.

Conclusions:

- Participants' schema of an office influenced their memory of it.

- They did not recall the wine and picnic basket because it is not part of their “typical office” schema.

Evaluation:

- Strengths:

- Strict control over variables --> to determine cause & effect relationship

- Limitation:

- Laboratory setting artificial environment

- Task does not reflect daily activity

- This study provides evidence to support how our schemas can affect our cognition/cognitive processes, in particular memory.

- Our schemas influence what we recall in our memory.

- Strength of schema theory – there is many types of research evidence to support it.

Supporting Study 4: French and Richards (1933)

Introduce Study/Signpost:

- A further study demonstrating schematic influence is by French and Richards (1933).

- To investigate the schemata influence on memory retrieval.

- In the study there were three conditions:

- Condition 1: Participants were shown a clock with roman numerals and asked to draw from memory.

- Condition 2: The same procedure, except the participants were told beforehand that they would be required to draw the clock from memory.

- Condition 3: The clock was left in full view of the participants and just had to draw it.

- The clock used represented the number four with IIII, not the conventional IV.

- In the first two conditions, the participants reverted to the conventional IV notation, whereas in the third condition, the IIII notation, because of the direct copy.

- They found that subjects asked to draw from memory a clock that had Roman numerals on its face typically represented the number four on the clock face as “IV” rather than the correct “IIII,” whereas those merely asked to copy it typically drew “IIII.”

- French and Richards explained this result in terms of schematic knowledge of roman numerals affecting memory retrieval.

- The findings supported the idea that subjects in the copy condition were more likely than subjects in other conditions to draw the clock without invoking schematic knowledge of Roman numerals.

- Strict control over variables to determine cause & effect relationship

- Define strengths of schema theory:

- Supported by lots of research to suggest schemas affect memory processes knowledge, both in a positive and negative sense.

- Through supporting studies, schema theory was demonstrated in its usefulness for understanding how memory is categorized, how inferences are made, how stories are interpreted, memory distortions and social cognition.

- Define weaknesses of schema theory:

- Not many studies/research evidence that evaluate and find limitations of schema theory

- Lacks explanation

- It is not clear exactly

- how schemas are initially acquired

- how they influence cognitive processes

- how people choose between relevant schemas when categorising people

- Cohen (1993) argued that:

- The concept of a schema is too vague to be useful.

- Schema theory does not show how schemas are required. It is not clear which develops first, the schema to interpret the experiences or vice versa.

- Schema theory explains how new information is categorised according to existing knowledge.

- But it does not account for completely new information that cannot link with existing knowledge.

- Therefore, it does not explain how new information is organised in early life

- E.g. language acquisition

- Thus schemas affect our cognitive processes and are used to organize our knowledge, assist recall, guide our behaviour, predict likely happenings and help make sense of current experiences helps us understand how we organize our knowledge.

- In conclusion, strengths of schema theory:

- Provides an explanation for how knowledge is stored in the mind something that is unobservable and remains unknown in psychology

- There is much research that supports schema theory

- But its limitations are that,

- It is unclear exactly how schemas are acquired and how people choose between schemas

- It does not account for new information without a link to existing schemas

- Overall, with the amount of evidence, schema theory should be considered an important theory that provides insight into information processing and behaviour.

- It has contributed largely to our understanding of mental processes.

- But the theory requires further research and refinements to overcome its limitations and uncover its unclear aspects

Piaget’s Schema & Learning Theory: 3 Fascinating Experiments

Piagetian approaches to learning as a process of actively constructing knowledge have been particularly effective in education, where they challenged traditional methods of teaching that overlooked the importance of the child’s role as a learner.

In this article, you’ll gain a complete understanding of basic Piagetian theory and the strong body of experimental evidence supporting its application.

Before you continue, we thought you might like to download our three Positive Psychology Exercises for free . These science-based exercises explore fundamental aspects of positive psychology, including strengths, values, and self-compassion, and will give you the tools to enhance the wellbeing of your clients, students, or employees.

This Article Contains:

Piaget’s learning theory & constructivism, what are schemas in piaget’s theory 4 examples, assimilation, accommodation, & equilibrium, piaget’s theory vs vygotsky’s, 3 fascinating experiments exploring piaget’s theories, implications in education, 3 best books on the topic, positivepsychology.com’s relevant resources, a take-home message.

Jean Piaget’s theory of cognitive development remains among the most complete and influential theories describing how the human mind shapes and develops through the process of learning.

At the University of Geneva in the 1960s, Piaget employed elegant experimental techniques and keen observational insight to analyze the moving pieces of cognitive development in children (Scott & Cogburn, 2021).

A biologist by training, Piaget took a pragmatic and mechanistic approach to understanding how the advanced architecture of human cognition develops, looking past the intuitive conception of the mind as something apparently complex and unapproachable to see simple and ordered principles of organization lying underneath (Scott & Cogburn, 2021).

At the core of Piaget’s theory are stages of development (Malik & Marwaha, 2021; Scott & Cogburn, 2021), a series of overall states of increasing cognitive sophistication defined principally by how the developing human ‘knows’ (i.e., understands) the world.

Learning is both the cognitive activity that occurs during these stages and the process of moving between stages. In each stage, children use a different set of cognitive tools to investigate and interpret the world and construct knowledge based on that interpretation. This, in turn, unlocks more sophisticated cognitive tools for more sophisticated learning, and so on.

The ultimate goal of this process of learning is to construct the most complete and accurate internal model of the world available at the time (Gandhi & Mukherji, 2021; Scott & Cogburn, 2021).

Sensorimotor period

The first stage occurs between birth to two years of age. In this stage, children understand their world only as far as simple physical interactions allow. For example, the world may be represented as things that can be touched and things that can be thrown .

The development of motor skills during this period allows the physical representation of the sensorimotor period to become more elaborate and finely tuned, with many potential ways of representing the world relating to different actions.

Preoperational period

In the preoperational period, occurring between two and seven years of age, children begin to understand the world using basic symbols and physical actions.

This marks the development of a more complex form of cognition but does not constitute the more advanced mental operations that emerge later in childhood (hence ‘pre-operational’).

Symbols include words, gestures, and simple imagery, and become increasingly governed by logic throughout the period.

Concrete operational period

Between 7 and 11 years of age, children begin to perform mental operations: internalized actions that are abstract and reversible. Children gain the ability to run simulations on their mental model of the world, which can be manipulated freely.

These mental operations follow a strict logical framework, and the content of these operations typically only represent concrete (i.e., ‘real’) objects.

Formal operational period

Between 11 and 15 years of age, children develop their ability to perform mental operations and expand the scope of the content of these operations to include abstract (e.g., mathematical or social concepts) and concrete objects.

Furthermore, they gain the ability to perform mental operations on mental operations themselves, such as evaluating the likelihood of something represented by a mental operation and comparing one mental operation with another.

Constructivism

A recurring theme throughout Piaget’s theory is the notion that learning is a process of construction, where the thing being constructed is the child’s internal model of the world or ‘reality’ more generally. This foundational theoretical assumption is called ‘constructivism’ (Gandhi & Mukherji, 2021).

Constructivism frames learning not as a process of absorbing knowledge that’s already out there in the world, but rather as a process of making knowledge from scratch.

This is done by using whatever cognitive tools learners have at their disposal to interpret incoming information and translate it into knowledge. Before it is interpreted, this incoming information lacks any objective content of knowledge; knowledge is something that is made after the fact.

This is contrary to the more traditional notion of learning as an individual receiving knowledge from a more knowledgeable source, such as a teacher in a classroom.

From the constructivist perspective, teachers are not a source of knowledge, but rather a source of information. Whether that information becomes knowledge or meaningless noise depends on the experience of the learner.

This framework comprises distinct structures of knowledge called schemas, which are organized and generalizable sets of knowledge about certain concepts. They typically contain a set of instructions or logical statements about a concept, as well as knowledge that can be applied to any instance of that concept.

Generalizability highlights the key function of schemas: an up-to-date set of instructions and ideas about as much of the world as possible, which can be used to predict and navigate the world in the future. Considering this, learning could more precisely be described as the process of keeping schemas up to date and developing new schemas where necessary (Scott & Cogburn, 2021).

While schemas are a constant feature of each stage of cognitive development, they change in content and sophistication, just as the stages do.

In the sensorimotor stage, a schema might be chewing, which encodes a set of instructions relating to how to chew and the motivations for chewing (e.g., chewing feels satisfying and stimulates hunger).

Within the schema for chewing are relevant categories of information, such as sets of objects that can and can’t be chewed. Likewise, objects that can be chewed might contain further categories: those that taste good, those that are particularly soft, and so on. All of the pertinent information for chewing is contained in the schema.

A preoperational stage schema might involve instructions for basic forms of communication. For example, a preoperational schema might involve all the information pertinent to waving, including what waving represents in a basic sense, when to wave, and the basic physical actions involved.

In the concrete operational period, schemas contain more detailed representations of the properties of objects. For example, a concrete operational schema for flowers might contain the typical features uniting all flowers, such as shapes, colors, locations, and also features that depend on mental operations, such as when it is appropriate to pick a flower and what to expect when a flower is given to a friend.

Finally, a formal operational schema might describe any number of abstract concepts. An example might be a schema containing abstract instructions for moral behavior that are described not only in basic physical or egocentric terms, but also involving religious ideals, non-egocentric ideas (e.g., empathy), and more abstract consequences and motivations for behaving morally.

Download 3 Free Positive Psychology Exercises (PDF)

Enhance wellbeing with these free, science-based exercises that draw on the latest insights from positive psychology.

Download 3 Free Positive Psychology Tools Pack (PDF)

By filling out your name and email address below.

Another constant feature described in Piaget’s theory are the actual processes by which schemas are updated with newly constructed knowledge (Scott & Cogburn, 2021).

Overall, these processes are known as adaptation, which is another way to describe using the most sophisticated cognitive tools available to keep schemas up to date. Adaptation involves two complementary sub-processes: assimilation and accommodation (Scott & Cogburn, 2021).

Assimilation is the process of integrating new knowledge into existing schemas by editing the new knowledge to ensure an acceptable fit.

In other words, assimilation involves updating schemas without changing the structure of those schemas. This is a common process; to an extent, all our cognition is constrained by basic universal rules and principles that create a fundamental unchanging cognitive structure, and it is useful to use these rules to ‘warp’ knowledge in order to fit.

Some schemas are resistant to change due to personal significance or simply because it may be easier to edit new knowledge rather than overhaul the existing mental organization.

Accommodation, in contrast, is the process of adjusting the cognitive organization of schemas in response to new knowledge. This occurs when the existing structure cannot account for the new information, rendering assimilation impossible.

As a simple example, a child may have a schema for birds that includes everything with wings and a schema for mammals that includes everything without wings. When they are presented with a bat, they are faced with a fundamental contradiction of this organization and have to reshuffle their cognitive structures to accommodate and make sense of this shared feature.

These two sub-processes occur in a cycle, as accommodation creates and reshapes the cognitive structure of schemas, which helps assimilate new knowledge, until accommodation is again necessary, and so on.

The goal of this cycle is to maintain as much equilibrium as possible, where there is no conflict between new knowledge and existing knowledge. This state of equilibrium can never be perfect, but learning is the act of trying to make it increasingly stable.

Piaget’s schema – Sprouts

Piaget’s work is commonly compared with that of Lev Vygotsky, another influential learning theorist conducting research at a similar time.

Their theoretical approaches are both primarily concerned with how knowledge is constructed and reject the traditional notion of knowledge as something that is transferred from one individual to another.

However, while Piaget emphasized that knowledge is constructed by the individual and shaped by existing cognitive structures (schemas) that organize the experiences of that individual, Vygotsky saw knowledge construction occurring elsewhere.

Vygotsky’s theory asserts that knowledge is constructed in the individual’s immediate social environment and shaped and interpreted by the individual’s use of language.

In Vygotsky’s theory, language takes the place of Piaget’s cognitive tools and actions. According to Vygotsky, individuals know the world through language, and the extent to which they know the world is mediated by the extent to which they can use language (Stewin & Martin, 1974; Lourenço, 2012).

Importantly, when considering the inherently social aspect of language, it follows that other individuals in someone’s immediate social context would be equally influential in how the individual knows the world.

As a result, in the place of internal stages of development, Vygotsky described external zones of development: social contexts within which individuals can use language to construct knowledge and develop, expanding the scope to include a broader social context for development, and so on.

Piaget and Vygotsky’s approaches are not wholly mutually exclusive, as a Piagetian theorist must acknowledge the influence of context in constructing knowledge, just as Vygotskyian theorists must acknowledge the influence of individual experience in constructing knowledge.

Likewise, this works in reverse, meaning that cognitive development becomes evident through observing how an individual apparently perceives the world.

A foundational experiment underlying Piaget’s theory examines differences in the ability to understand conservation of quantity. Children younger than seven were shown a row of squares and a row of circles of equal quantity. They were correctly able to identify that there were the same number of squares as circles.

However, when the experimenter moved the squares further apart, making a row of greater length, the children now answered that there were more squares than circles.

Because they lack the ability for reversible mental operations developed in the concrete operational stage, changing the appearance of the squares to make the space they occupied larger was sufficient justification for the children to conclude there were more (Kubli, 1979, 1983).

Other experiments have similarly shown how comprehending conservation changes as a function of developmental changes in how the world is represented. For example, another experiment showed children a pair of rods of identical length, placed side by side to demonstrate their equivalence. One of the rods was then displaced so that its position was nearer and therefore appeared longer.

Children younger than six were able to correctly identify the rods as equivalent length when they were side by side, but when displaced, they concluded one rod had become larger. Some slightly older children suggested the rods may become equivalent length again if the displaced rod was returned to its original position, demonstrating their development of reversibility.

Finally, the oldest children concluded that length was an invariant property that was conserved regardless of how the rod was displaced, showing a confident grasp of both reversibility and conservation (Kubli, 1979, 1983).

Another experiment clearly illustrates the development and refinement of schemas that accompany the transition between stages in Piaget’s theory. Children were presented with a picture featuring a bunch of flowers consisting of five asters and two tulips. They were then asked whether there were more asters in the picture or more flowers.

In children younger than roughly eight years of age, the typical answer is that there are more asters, demonstrating that these children have not yet developed the ability to comprehensively categorize the world into schemas of related objects and concepts, and therefore do not recognize that flowers should be a category inclusive of asters (Politzer, 2016).

Here are a few considerations of specific importance (Kubli, 1979).

The development of the ability to comprehend invariance and reversibility defines much of the content of Piaget’s stages . The development of these concepts reflects children’s understanding of rules that extend throughout the world and provide a fundamental basis for reality, and the development of the mental operations necessary to reason based on these rules.

As a result, teachers should adopt an approach that closely follows their students’ search for invariant rules and experimentation with reversibility. Teachers should not adopt a heavy-handed approach where they walk their students through these rules, nor should they become too detached from their students’ development and assume certain types of knowledge that their students may not have discovered yet.

Instead, the process of teaching should be a journey characterized by the discovery and construction of new forms of knowledge.

In an applied education context, teachers should also be careful not to focus too strongly on the theoretical assumptions of constructivism. While constructivism emphasizes the role of the learner as an individual, learning often occurs in a social context alongside a class.

Consequently, although learners are engaged in the construction of their own knowledge, they will inevitably try to model their knowledge on others and form theories about the world that are acceptable and relatable to others. Teachers should, therefore, remain aware that their assumptions and attitudes as educators remain highly influential in a constructivist framework.

To get an in-depth understanding of Piaget’s Schema & Learning Theory, we suggest investing in the following books:

1. The Psychology of the Child – Jean Piaget and Bärbel Inhelder

The Psychology of the Child provides the most accessible means of studying Piaget’s original work underlying his influential theory.

While contemporary writers may do a better job of putting Piagetian theory in context, when it comes to understanding and engaging with the theory itself, there is no substitute to reading about it in the words of the seminal psychologist himself.

Find the book on Amazon .

2. Children’s Thinking – Robert Siegler

Children’s Thinking provides a solid academic reference for a variety of theoretical approaches to cognitive development, including Piagetian theory.

It’s rarely useful to take a single-track approach to psychology, and your understanding and application of Piagetian theory will be improved greatly by learning about other theories of childhood cognition and development, which through their differences or similarities help to delineate Piaget’s ideas.

3. Constructivism: Theory, Perspectives and Practice – Catherine Fosnot

This book by Catherine Fosnot is a comprehensive and practical text analyzing the fundamental assumptions and applications of constructivist epistemology.

Studying the epistemological assumptions underlying psychological theory can seem like a chore, but it is absolutely vital in order to engage with your knowledge and develop a confident and flexible approach to applying Piagetian theory.

Fortunately, Fosnot’s insightful description and commentary are anything but a chore to read.

On our site, we have many relevant resources that will give a more solid theoretical background and also provide practical ways to apply theory. Here are a few recommended reads:

- Developmental Psychology 101: Theories, Stages, & Research provides a great alternative to the suggested reading above if you want a more digestible overview of the predominant theories of cognitive development and valuable insight into the broader theoretical context alongside Piaget’s ideas.

- Applying Positive Psychology in Schools & Education is a comprehensive guide to applying your knowledge of psychological theory in education. If you are learning about Piagetian theory as an educator, this article will provide essential further reading for developing the ideas you’ve learned here.

- Top 37 Educational Psychology Books, Interventions, & Apps is an excellent resource if you want to go beyond the recommended books listed above. Educational psychology is a truly vast topic, with many fascinating ideas to explore in a variety of media, and this article will help you begin your deeper exploration of the topic.

If you’re looking for more science-based ways to help others enhance their wellbeing, check out this signature collection of 17 validated positive psychology tools for practitioners. Use them to help others flourish and thrive.

World’s Largest Positive Psychology Resource

The Positive Psychology Toolkit© is a groundbreaking practitioner resource containing over 500 science-based exercises , activities, interventions, questionnaires, and assessments created by experts using the latest positive psychology research.

Updated monthly. 100% Science-based.

“The best positive psychology resource out there!” — Emiliya Zhivotovskaya , Flourishing Center CEO

Piaget’s theory of cognitive development provides a comprehensive and useful theoretical framework for thinking deeply about how information is translated to knowledge in the developing mind.

This has important implications for education, as having a clear theoretical framework for understanding how children learn helps make teaching a more structured and efficient activity for both teachers and students alike.

More generally, Piaget’s ideas also highlight the importance of considering the different ways individuals can have knowledge of the world, depending on their stage of development and methods of learning.

We hope you enjoyed reading this article. Don’t forget to download our three Positive Psychology Exercises for free .

- Fosnot, C. T. (2005). Constructivism: Theory, perspectives, and practice (2nd ed.). Teachers College Press.

- Gandhi, M. H., & Mukherji, P. (2021). Learning theories . StatPearls. Retrieved November 5, 2021, from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK562189/

- Kubli, F. (1979). Piaget’s cognitive psychology and its consequences for the teaching of science. European Journal of Science Education , 1 (1), 5–20.

- Kubli, F. (1983). Piaget’s clinical experiments: A critical analysis and study of their implications for science teaching. European Journal of Science Education , 5 (2), 123–139.

- Lourenço, O. (2012). Piaget and Vygotsky: Many resemblances, and a crucial difference. New Ideas in Psychology , 30 (3), 281–295.

- Malik, F., & Marwaha, R. (2021). Cognitive development . StatPearls. Retrieved November 5, 2021, from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537095/

- Piaget, J., & Inhelder, B. (1969). The psychology of the child. Basic Books.

- Politzer, G. (2016). The class inclusion question: A case study in applying pragmatics to the experimental study of cognition. SpringerPlus , 5 (1), 1133.

- Scott, H. K., & Cogburn, M. (2021). Piaget . StatPearls. Retrieved November 5, 2021, from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448206/

- Siegler, R. S. (1997). Children’s thinking (3rd ed.). Prentice Hall.

- Stewin, L. L., & Martin, J. (1974). The developmental stages of L. S. Vygotsky and J. Piaget: A comparison. Alberta Journal of Educational Research , 20 (4), 348–362.

Share this article:

Article feedback

What our readers think.

Hello! Thanks for the great article. However, I have an observation. I’m a teacher in a government primary school. I wish there had more information about how I can use this theory in my lesson plan or in education.

Glad you enjoyed the article! I will make sure our writing team will receive your feedback 🙂 Kind regards, Julia | Community Manager

Let us know your thoughts Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published.

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Related articles

The Hidden Costs of Sleep Deprivation & Its Consequences

In the short term, a lack of sleep can leave us stressed and grumpy, unwilling, or unable to take on what is needed or expected [...]

Circadian Rhythm: The Science Behind Your Internal Clock

Circadian rhythms are the daily cycles of our bodily processes, such as sleep, appetite, and alertness. In a sense, we all know about them because [...]

What Is the Health Belief Model? An Updated Look

Early detection through regular screening is key to preventing and treating many diseases. Despite this fact, participation in screening tends to be low. In Australia, [...]

Read other articles by their category

- Body & Brain (50)

- Coaching & Application (58)

- Compassion (25)

- Counseling (51)

- Emotional Intelligence (23)

- Gratitude (18)

- Grief & Bereavement (21)

- Happiness & SWB (40)

- Meaning & Values (26)

- Meditation (20)

- Mindfulness (44)

- Motivation & Goals (45)

- Optimism & Mindset (34)

- Positive CBT (30)

- Positive Communication (22)

- Positive Education (47)

- Positive Emotions (32)

- Positive Leadership (19)

- Positive Parenting (16)

- Positive Psychology (34)

- Positive Workplace (37)

- Productivity (18)

- Relationships (44)

- Resilience & Coping (39)

- Self Awareness (21)

- Self Esteem (38)

- Strengths & Virtues (32)

- Stress & Burnout Prevention (34)

- Theory & Books (46)

- Therapy Exercises (37)

- Types of Therapy (64)

3 Positive Psychology Tools (PDF)

Schema Theory In Psychology

Charlotte Nickerson

Research Assistant at Harvard University

Undergraduate at Harvard University

Charlotte Nickerson is a student at Harvard University obsessed with the intersection of mental health, productivity, and design.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

- A schema is a knowledge structure that allows organisms to interpret and understand the world around them. Schemata is a method of organizing information that allows the brain to work more efficiently.

- Piaget’s theory of cognitive development put the concept at the forefront of cognitive science. Contemporary conceptions of schema evolved in the 1970s and 1980s.

- The widespread use of computers in the last decades of the 20th century also affected theories of how people store and use information in the brain.

- There are four main types of schemas. These are centered around objects, the self, roles, and events.

- Schemas can be changed and reconstructed throughout a person’s life. The two processes for doing so are assimilation and accommodation.

- Schemas have been pivotal in influencing theories of learning as well as in teacher instruction methods.

Historical Background

Schema theory is a branch of cognitive science concerned with how the brain structures knowledge. Schema (plural: schemas or schemata) is an organized unit of knowledge for a subject or event based on past experience.

Individuals access schema to guide current understanding and action (Pankin, 2013). For example, a student’s self-schema of being intelligent may have formed due to past experiences of teachers praising the student’s work and influencing the student to have studious habits.

Information that does not fit into the schema may be comprehended incorrectly or even not at all.

For example, if a waiter at a restaurant asked a customer if he would like to hum with his omelet, the patron may have a difficult time interpreting what he was asking and why, as humming is not typically something that patrons in restaurants do with omelets (Widmayer, 2001).

The concept of a schema can be traced to Plato and Aristotle (Marshall, 1995); nonetheless, scholars consider Kant (1929) to be the first to talk about schemas as organizing structures that people use to mediate how they see and interpret the world (Johnson, 1987).

F.C. Bartlett, in his book Remembering (1932), was the first to write extensively about schemas in the context of procedural memory. Procedural memory is a part of long-term memory responsible for organisms knowing how to control their bodies in certain ways in order to accomplish certain tasks, also known as motor skills.

The Swiss psychologist Jean Piaget , best known for his work on child development, was the first to create a cognitive development theory that included schemas.

Piaget (1976) saw schemas as mental structures altered by new information. In Piaget’s theory, new information can be added or assimilated into current schemas — ideas people have about how the world functions.

However, new information that cannot be integrated into an organism’s current schemas can create cognitive dissonance. When this happens, the schemas must change to accommodate new information.

Characteristics of Schemas

The theorists of the 1970s and 1980s conceptualized schemas as structures for representing broad concepts in memory (Ortony, 1977; McVee, Dunsmore, and Gavelek, 2005).

This definition highlights several important features of schemas, as noted by Rumelhart (1984):

- Schemas have variables,

- Schemas can be embedded, one within another,

- Schemas represent knowledge at all levels of abstraction,

- Schemas represent knowledge rather than definitions,

- Schemas are active processes,

- Schemas are recognition devices whose processing is aimed at evaluating how well new information fits into itself.

Piaget developed the notion of schemata, mental “structures,” which act as frameworks through which the individual classifies and interprets the world. It is these schemas that allow us, for instance, to distinguish between horses and cows by looking for key characteristics.

A schema can be discrete and specific or sequential and elaborate. For example, a schema may be as specific as recognizing a dog or as elaborate as categorizing different types of dogs.

For example, when a parent reads to a child about dogs, the child constructs a schema about dogs.

On a more sophisticated level, the schema allows us to interpret geographical features, understand complex mathematical formulae, and understand acceptable behavior associated with particular roles and contexts.

Piaget argues that, as we grow and mature, our schemata become increasingly more complex and intricate, allowing us access to more sophisticated understandings and interpretations of the world.

A baby, for instance, has only its innate schema through which to interpret and interact with its environment, such as grasping and sucking. As that baby grows, however, new schemas develop and become more complex.

For instance, it will learn to distinguish objects and people and manipulate its surroundings.

As it develops further, the child will develop the schemata necessary to deal with more abstract and symbolic concepts, such as spoken (and later, written) language, together with mathematical and logical reasoning.

Schema and Culture

People develop schemas for their own and other cultures. They may also develop schemas for cultural understanding. Cultural information and experiences are stored and schemas and support cultural identity.

Once a schema is formed, it focuses people’s attention on the aspects of the culture they are experiencing and by assimilating, accommodating, or rejecting aspects that don’t conform.

For example, someone growing up in England may develop a schema around Christmas involving crackers, caroling, turkey, mince pies, and Saint Nicholas.

This schema may affirm their cultural identity if they say, spend Christmas in Sicily, where a native schema of Christmas would likely involve eating several types of fish.

A schema used for cultural understanding is more than a stereotype about the members of a culture.

While stereotypes tend to be rigid, schemas are dynamic and subject to revision, and while stereotypes tend to simplify and ignore group differences, a schema can be complex (Renstch, Mot, and Abbe, 2009).

There are several types of schemata.

Event schema

Event schemas often called cognitive scripts, describe behavioral and event sequences and daily activities. These provide a basis for anticipating the future, setting objectives, and making plans.

For example, the behavior sequence where people are supposed to become hungry in the evening may lead someone to make evening reservations at a restaurant.

Event schemata are automatic and can be difficult to change, such as texting while driving.

Event schemata can vary widely among different cultures and countries. For example, while it is quite common for people to greet one another with a handshake in the United States, in Tibet, you greet someone by sticking your tongue out at them, and in Belize, you bump fists.

Self-schema

Self-schema is a term used to describe the knowledge that people accumulate about themselves by interacting with the natural world and with other human beings.

In turn, this influences peoples’ behavior towards others and their motivations.

Because information about the self continually comes into a person’s mind as a result of experience and social interaction, the self-schema constantly evolves over the lifespan (Lemme, 2006).

Object schema

Object schema helps to interpret inanimate objects. They inform people’s understanding of what objects are, how they should function, and what someone can expect from them.

For example, someone may have an object schema around how to use a pen.

Role schema

Role schemas invoke knowledge about how people are supposed to behave based on their roles in particular social situations (Callero, 1994).

For example, at a polite dinner party, someone with the role of the guest may be expected not to put their elbows on the table and to not talk over others.

How Schemas Change

Piaget argued that people experience a biological urge to maintain equilibrium, a state of balance between internal schema and the external environment – in other words, the ability to fully understand what’s going on around us using our existing cognitive models.

Through the processes of accommodation and assimilation, schemas evolve and become more sophisticated.

- In assimilation , new information becomes incorporated into pre-existing schemas. The information itself does not change the schema, as the schema already accounts for the new information. Assimilation promotes the “status quo” of cognitive structures (Piaget, 1976).

For organisms to learn and develop, they must be able to adapt their schemas to new information and construct new schemas for unfamiliar concepts.

Piaget argues that, on occasions, new environmental information is encountered that doesn’t match neatly with existing schemata, and we must consequently adjust and refine these schemas using the accommodation.

- In accommodation , existing schemas may be altered or new ones formed as a person learns new information or has new experiences. This disrupts the structure of pre-existing schemas and may lead to the creation of a new schema altogether.

Generally, psychologists believe that schemas are easier to change during childhood than later in life. They may also persist despite encounters with evidence that contradicts an individual’s beliefs.

Consequently, as people grow and learn more about their world, their schemata become more specialized and refined until they are able to perform complex abstract cognitions.

It is important to note, however, that – according to Piaget – the refinement of schemata does not occur without restrictions; at different ages, we are capable of different cognitive processes – and the extent of our schemata is consequently limited by biological boundaries.

Consequently, the reason that 6-year-old rocket scientists are thin on the ground is that the differences between the mental abilities of children and adults are qualitative as well as quantitative.

In other words, development is not just governed by the amount of information absorbed by the individual but also by the types of cognitive operation that can be performed on that information.

These operations are, in turn, determined by the age of the child and their resultant physiological development. Piaget consequently argues that as children age, they move through a series of stages, each of which brings with them the ability to perform increasingly more sophisticated cognitive operations.

How Schemas Affect Learning

Several instructional strategies can follow from schema theory. One of the most relevant implications of schema theory to teaching is the role that prior knowledge plays in students’ processing of information.

For learners to process information effectively, something needs to activate their existing schemas related to the new content. For instance, it would be unlikely that a student would be able to fully interpret the implications of Jacobinism without an existing schema around the existence of the French Revolution (Widmayer, 2001).

This idea that schema activation is important to learning is reflected in popular theories of learning, such as the third stage of Gagne’s nine conditions of learning , “Stimulating Recall of Prior Knowledge.”

Learners under schema theory acquire knowledge in a similar way to Piaget’s model of cognitive developments. There are three main reactions that a learner can have to new information (Widmayer, 2001):

- Accreditation : In accreditation, learners assimilate a new input into their existing schema without making any changes to the overall schema.

- For example, a learner learning that grass blades and tree leaves undergo photosynthesis may not need to change their schema to process this information if their photosynthesis schema is that “all plants undergo photosynthesis.”

- Many teachers even use “metacognitive” strategies designed to activate the learner’s schema before reading, such as reading a heading and the title, looking at visuals in the text, and making predictions about the text based on the title and pictures (Widmayer, 2001).

- Another way of pre-activating schema encourages the use of analogies and comparisons to draw attention to the learner’s existing schema and help them make connections between the existing schema and the new information (Armbruster, 1996; Driscoll, 1997).

- Tuning : Tuning is when learners realize that their existing schema is inadequate for the new knowledge and thus modify their existing schema accordingly.

- For example, someone may learn that a particular proposition is nonsensical in a particular sentence structure and thus need to modify their schema around when it is and is not appropriate to use that proposition.

- Scholars have noted that the transfer of knowledge outside of the context in which it was originally acquired is difficult and may require that learners be exposed to similar knowledge in numerous different contexts to eventually be able to construct less situationally constricted schema (Price & Driscroll, 1997).

- Restructuring : Finally, restructuring is the process of creating a new schema that addresses the inconsistencies between the old schema and the newly acquired information.

- For example, a learner who learns that corn is technically a fruit may need to overhaul their entire schema of fruit to address the inconsistencies between how they had previously defined fruit and this new information.

Unlike Piaget, schema theorists do not see each schema as representative of discrete stages of development, and the processes of accreditation, tuning, and restructuring happen over multiple domains in a continuous time frame (Widmayer, 2001).

According to schema theory, Knowledge is not necessarily stored hierarchically. Rather, knowledge is driven by the meanings attached to that knowledge by the learner and represented propositionally and in a way that is actively constructed by the learner.

In addition to schema, psychologists believe that learners also have mental models — dynamic models for problem-solving based on a learner’s existing schema and perceptions of task demand and task performance.

Rather than starting from nothing, people have imprecise, partial, and idiosyncratic understandings to tasks that evolve with experience (Driscoll, 1994).

Critical Evaluation

While schema theory gives psychologists a framework for understanding how humans process knowledge, some scholars have argued that it is ill-constrained and provides few assumptions about how this processing actually works.

This lack of constraint, it has been argued, allows the theory enough flexibility for people to explain virtually any set of empirical data using the theory.

The flexibility of schema theory also gives it limited predictive value and, thus, a limited ability to be tested as a scientific theory (Thorndyke and Yekovich, 1979).

Thorndyke and Yekovich (1979) elaborate on the shortcomings of a schema as a predictive theory. In the same vein as the criticism about the flexibility of schema theory, Thorndyke and Yekovich note that it is difficult to find data inconsistent with schema theory and that it has largely been used for descriptive purposes to account for existing data.

Lastly, Thorndyke and Yekovich (1979) argue that the second area of theoretical weakness in Schema theories lies in its specification of detailed processes for manipulating and creating schemas.

One competing theory to the schema theory of learning is Ausubel’s Meaningful Receptive Learning Theory (1966). In short, Ausubel’s Meaningful Reception Learning Theory states that learners can learn best when the new material being taught can be anchored into existing cognitive information in the learners.

In contrast to Ausbel’s theory, the learner in schema theory actively builds schemas and revises them in light of new information. As a result, each individual’s schema is unique and dependent on that individual’s experiences and cognitive processes.

Ausubel proposed a hierarchical organization of knowledge where the learner more or less attaches new knowledge to an existing hierarchy. In this representation, structure, as well as meaning, drives memory.

Applications

Schemas are a major determinant of how people think, feel, behave, and interact socially. People generally accept their schemas as truths about the world outside of awareness, despite how they influence the processing of experiences.

Schema therapy, developed by Jeffrey E. Young (1990), is an integrative therapy approach and theoretical framework used to treat patients, most often with personality disorders. Schema therapy evolved from cognitive behavioral therapy.

Those with personality disorders often fail to respond to traditional cognitive behavioral theory (Beck et al., 1990). Rather than targeting acute psychiatric symptoms, schema therapy targets the underlying characteristics of personality disorders.

The schema therapy model has three main constructs: “schemas,” or core psychological themes; “coping styles,” or characteristic behavioral responses to schemas; and “modes,” which are the schemas and coping styles operating at a given moment (Martin and Young, 2009).

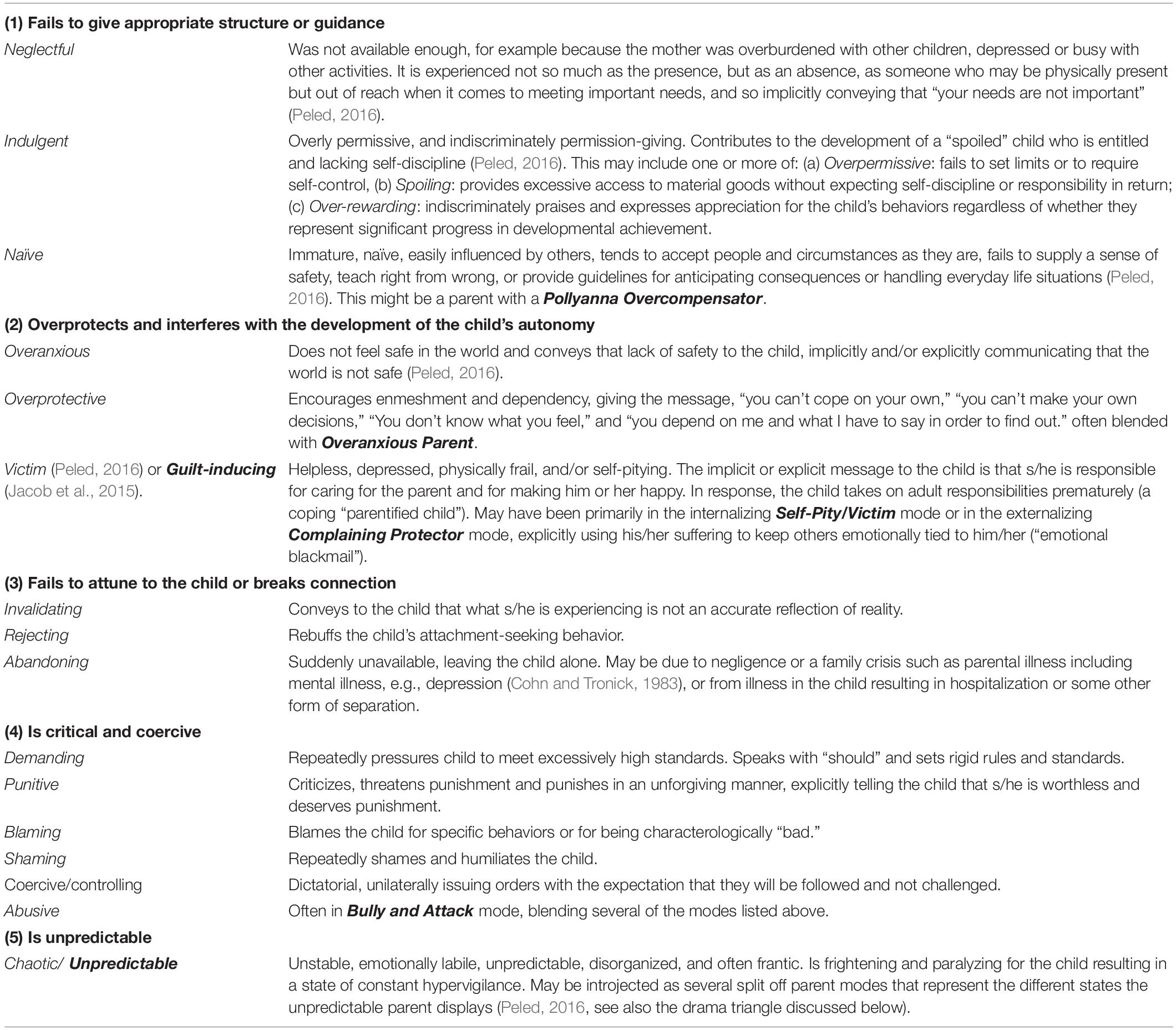

According to the schema therapy framework, the earliest and most central schemas tend to originate in one’s childhood. These schemas begin as representations of the child’s environment based on reality and develop from the interactions between a child’s innate temperament and specific unmet, core childhood needs (Martin and Young, 2009).

Schema therapy seeks to alter these long-standing schemas by helping people to:

- identify and heal their own schemas,

- identify and address coping styles that get in the way of emotional needs,

- change patterns of feeling and behaviors that result from schemas,

- learn how to get core emotional needs met in a healthy and adaptive way,

- and learn how to cope healthily with frustration and distress when certain needs cannot be met.

Alba, J. W., & Hasher, L. (1983). Is memory schematic? . Psychological Bulletin, 93 (2), 203.

Armbruster, B. B. (1986). Schema theory and the design of content-area textbooks . Educational Psychologist, 21 (4), 253-267

Ausubel, D. P. (1966). Meaningful reception learning and the acquisition of concepts. In Analyses of concept learning (pp. 157-175). Academic Press.

Bartlett, F. C., & Bartlett, F. C. (1995). Remembering: A study in experimental and social psychology . Cambridge University Press.

Beck, A. T., Freeman, A., & Associates. (1990). Cognitive therapy of personality disorders . New York: Guilford Press.

Brewer, W. F., & Treyens, J. C. (1981). Role of schemata in memory for places. Cognitive Psychology, 13 (2), 207-230.

Driscoll, M. P. (1994). Psychology of learning for instruction . Allyn & Bacon.

Gagne, R. M., & Glaser, R. (1987). Foundations in learning research. Instructional technology: foundations , 49-83.

Halliday, M. A. K., & Hasan, R. (1989). Language, context, and text: Aspects of language in a social-semiotic perspective .

Johnson, M. (1987). The body in mind: The bodily basis of meaning, imagination. Reason .

Kant, I. (1929). Critique of Pure Reason (1781-1787), Trans. Kemp Smith.

Kaplan, R. B. (1966). Cultural thought patterns in intercultural education. Language Learning, 16 (1), 1-20.

Lemme, B. H. (2006) Development in Adulthood . Boston, MA. Pearson Education, Inc

Marshall, S. P. (1995). Schemas in problem solving . Cambridge University Press.

Martin, R., & Young, J. (2009). Schema therapy. Handbook of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapies , 317.

McVee, M. B., Dunsmore, K., & Gavelek, J. R. (2005). Schema theory revisited. Review of Educational Research, 75 (4), 531-566.

Ortony, A., & Anderson, R. C. (1977). Definite descriptions and semantic memory. Cognitive Science, 1 (1), 74-83.

Pankin, J. (2013). Schema theory and concept formation. Presentation at MIT , Fall.

Piaget, J. (1976). Piaget’s theory. In Piaget and his school (pp. 11-23). Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

Price, E. A., & Driscoll, M. P. (1997). An inquiry into the spontaneous transfer of problem-solving skill. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 22 (4), 472-494.

Rentsch, J. R., Mot, I., & Abbe, A. (2009). Identifying the core content and structure of a schema for cultural understanding. ARMY RESEARCH INST FOR THE BEHAVIORAL AND SOCIAL SCIENCES ARLINGTON VA.

Rumelhart, D. E. (1975). Notes on a schema for stories. In Representation and understanding (pp. 211-236). Morgan Kaufmann.

Rumelhart, D. E. (1984). Schemata and the cognitive system .

Schank, R. C., & Abelson, R. P. (2013). Scripts, plans, goals, and understanding: An inquiry into human knowledge structures . Psychology Press.

Schank, R. C. (1982). Reading and understanding: Teaching from the perspective of artificial intelligence . L. Erlbaum Associates Inc.

Schwartz, N. H., Ellsworth, L. S., Graham, L., & Knight, B. (1998). Accessing prior knowledge to remember text: A comparison of advance organizers and maps. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 23 (1), 65-89.

Thorndyke, P. W., & Yekovich, F. R. (1979). A critique of schemata as a theory of human story memory (No. P-6307). Santa Monica, CA. Rand.

Widmayer, S. A. (2004). Schema theory: An introduction . Retrieved December 26, 2004.

Young, J. E. (1990). Cognitive therapy for personality disorders . Professional Resources Press. Sarasota, FL

Further Reading

- Baldwin, M. W. (1992). Relational schemas and the processing of social information. Psychological bulletin, 112(3), 461.

- Padesky, C. A. (1994). Schema change processes in cognitive therapy. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 1(5), 267-278.

Related Articles

Child Psychology

Vygotsky vs. Piaget: A Paradigm Shift

Interactional Synchrony

Internal Working Models of Attachment

Cognitive Psychology

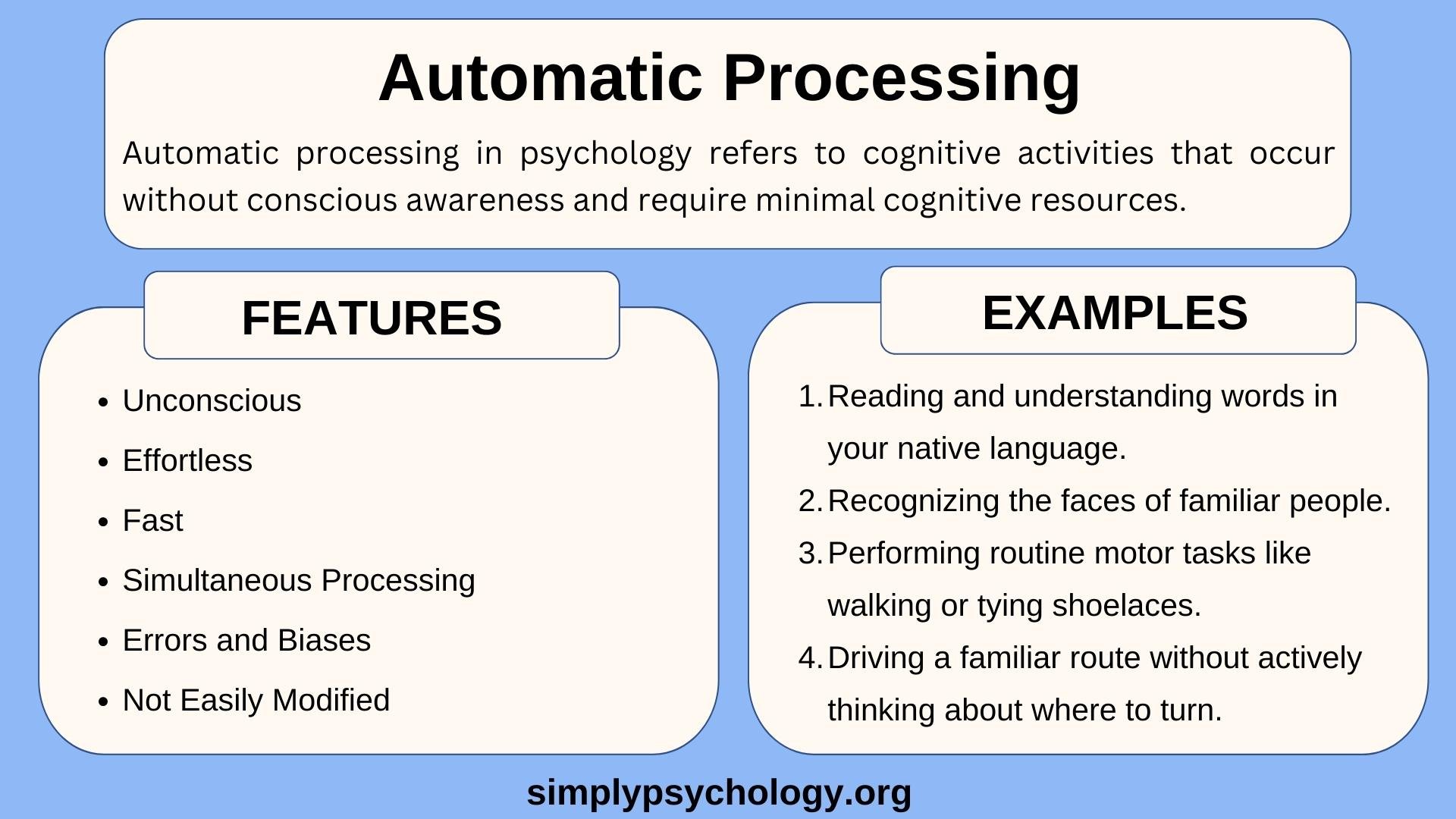

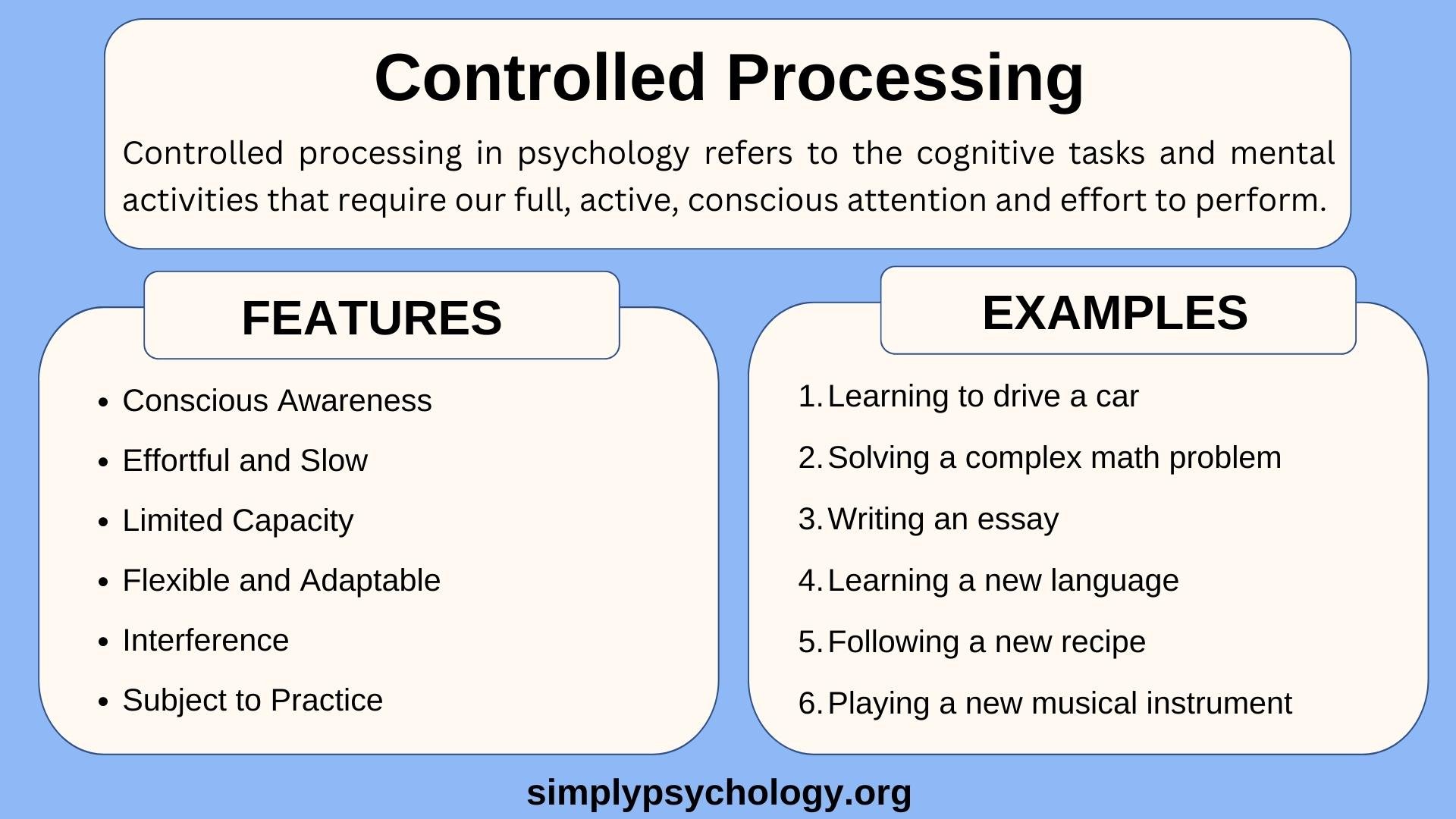

Automatic Processing in Psychology: Definition & Examples

Controlled Processing in Psychology: Definition & Examples

Learning Theory of Attachment

REVIEW article

Using schema modes for case conceptualization in schema therapy: an applied clinical approach.

- 1 Department of Psychology, Rhodes University, Makhanda, South Africa

- 2 Schema Therapy Institute, Cape Town, South Africa

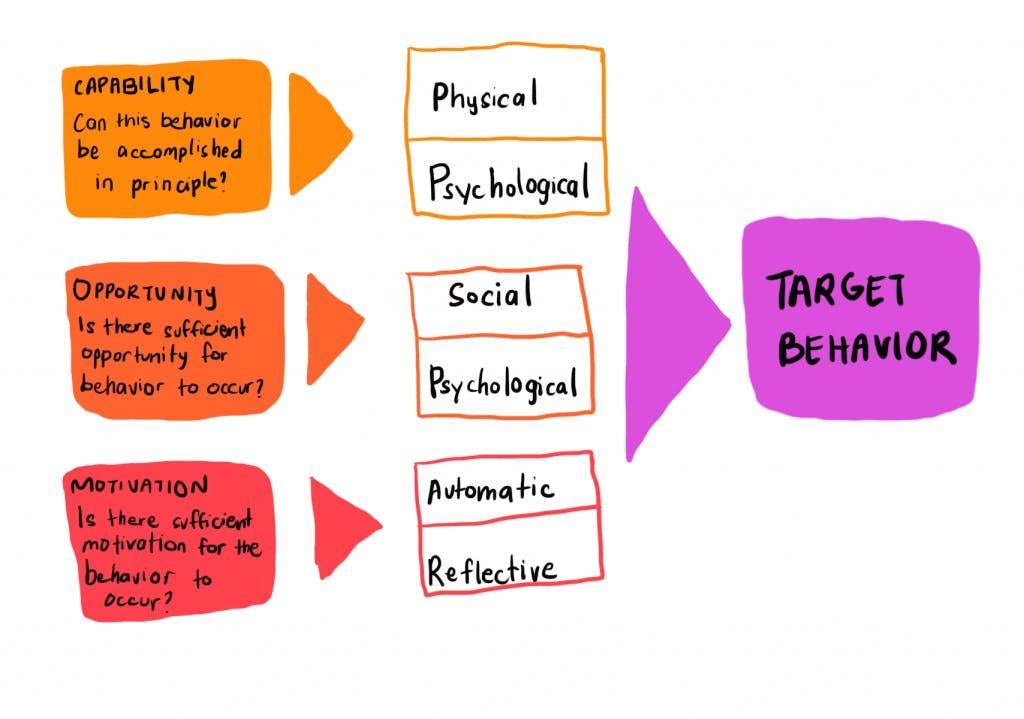

This article is situated within the framework of schema therapy and offers a comprehensive and clinically useful list of schema modes that have been identified as being relevant to conceptualizing complex psychological problems, such as those posed by personality disorders, and, in particular, the way that those problems are perpetuated. Drawing on the schema therapy literature, as well as other literature including that of cognitive behavior therapy and metacognitive therapy, over eighty modes are identified altogether, categorized under the widely accepted broad headings of Healthy Adult, Child modes, Parent modes and coping modes which are, in turn, divided into Surrender, Detached/Avoidant, and Overcompensator. An additional category is included: Repetitive Unproductive Thinking. This draws attention to the recognition by metacognitive therapists that such covert behaviors play a significant role in amplifying distress and perpetuating a range of psychological problems and symptoms. In addition to the modes themselves, several concepts are defined that are directly relevant to working with modes in practice. These include: default modes, blended modes, mode suites and mode sequences. Attention is also drawn to the way in which Child modes may be hidden “backstage” behind coping modes, and to the dyadic relationship between Child modes and Parent modes. Also relevant to practice are: (1) the recognition that Critic voices may have different sources and this has implications for treatment, (2) the concept of complex modes in which several submodes work together, and (3) the fact that in imagery work and image of a child may not represent a Vulnerable Child, but a Coping Child. The modes and mode processes described are directly relevant to clinical practice and, in addition to being grounded in the literature, have grown out of and proved to be of practical use in conceptualizing my own cases, and in supervising the cases of other clinicians working within the schema therapy framework.

Introduction

Schema therapy is an integrative therapy that is increasingly being shown to be of value with clinically challenging presentations including moderate to severe presentations of personality disorders and complex trauma ( Giesen-Bloo et al., 2006 ; Jacob and Arntz, 2013 ; Bamelis et al., 2014 ; Talbot et al., 2015 ; Keulen-de Vos et al., 2017 ; Peled et al., 2017 ; Huntjens et al., 2019 ; Simpson and Smith, 2020 ; Yakın et al., 2020 ; Bernstein et al., 2021 ). The identification and analysis of schema modes is central to schema therapy as a basis for case conceptualization and as a guide to practice. Schema modes are recognizable experiential states that express an underlying schema structure. The aim of this article is to present a comprehensive and clinically useful list of schema modes that have been identified in the clinical literature as relevant to conceptualizing psychological problems, and, in particular, to the way those problems are perpetuated, and that have proved to be of practical use in conceptualizing my own cases, and in supervising the cases of others.

Schema Modes as Structural Units

The idea that there are parts of the self was already widespread in Europe in the second half of the 19th century. In 1868, Durand, whom Pierre Janet regarded as one of the founders of hypnotherapy, described how beneath the “ego-in-chief” was a multitude of “subegos” which were out of awareness and “constituted our unconscious life” ( Ellenberger, 1970 , p. 168). Berne (1961 , p. 4), drawing on a concept developed by his mentor, Federn, used the term “ego-states” in his system of Transactional Analysis. He described three broad ego states, Parent, Adult and Child, which, as he pointed out, “are not just concepts but phenomenological realities,” that reflect real differences in the experience and behavior of the individual. This term is also the foundation of John and Helen Watkins’ ego-state therapy ( Watkins, 1993 ; Watkins and Watkins, 1997 ).

There is increasing recognition that a range of distinct modes underpin everyday experience and behavior ( Lazarus and Rafaeli, in press ), and a growing number of current therapy approaches examine how to identify and work with them ( Schwartz, 1997 ; Teasdale, 1999 ; Stiles, 2011 ). Referred to as schema modes within the schema therapy system, these “moment-to-moment emotional states that temporarily dominate a person’s thinking, feeling, and behavior” ( Keulen-de Vos et al., 2014 ) are generated by the system of schemas that is the source of the “understandable patterning of cognition and affect that has developed from the past and structures current experience” ( Stein and Young, 1997 , p. 162). Each mode is based on an underlying “organizational unit” so that an individual can repeatedly exhibit the same cognitive, emotional and behavioral pattern ( Lazarus et al., 2020 ). They are phenomenologically distinct: “each mode ‘feels different’,” observe Lazarus and Rafaeli (in press) , with “distinct subjectively experienced qualities.” Dysfunction occurs when a mode, as “a part of the self” is “cut off to some degree from other parts of the self” ( Young et al., 2003 , p. 40).

Differentiating Modes

When the concept of schema modes was introduced ( McGinn and Young, 1996 ; Young et al., 2003 ) a relatively small number were identified and described. Since then, however, researchers and clinicians have been describing and naming an increasing number. Concern has been expressed at the apparent proliferation of modes. As Roediger et al. (2018 , p. 42) point out, “if we use a close-up lens, we can distinguish an almost endless number of modes,” and this can be confusing for clinicians and clients alike. Lazarus and Rafaeli (in press) , however, point out the need to find “the balance between optimal distinctiveness and parsimony.” As they observe, this depends on the context, and “we don’t know yet” just what that balance is for therapists engaging with complex cases.

Focusing on a limited number of modes can simplify case conceptualization and communication with the client. However, there are also disadvantages. Modes described in broad terms, may appear quite differently from one individual to another, or within the same individual at different times, or may include what are actually sequences of distinct experiential states. Consider Simpson’s (2020, p. 47) account of the Helpless Surrenderer mode, the heart of which is a feeling of being dependent, helpless, and needing to be rescued. The mode also includes, “a mixture of surrender and over-compensatory behaviors,” Simpson suggests, and “can have a resigned or victim tone… [and] can manifest with different ‘flavors,’ e.g., aggrieved, passive-aggressive, histrionic (theatrical, ‘flouncy’), sullen (‘teenager’), entitled, hopeless, negative, or complaining, under a façade of deference or submissiveness.” Furthermore, an item from the scale for measuring this mode ( Simpson et al., 2018 ) includes a further feature, the hypervigilant attachment-seeking that may be a way of coping with abandonment: “I am very possessive and hold on to the people that are important to me.” Simpson is not describing a single, phenomenologically distinct experience, but a collection of modes that might occur together or in sequence. Such sweeping summaries under the heading of a single mode are not uncommon in the schema therapy literature.

Modes and Their Relationships

There is consensus about the broad classification of modes under the headings of Healthy Adult, Child modes, Parent modes and Coping modes. Coping modes are divided into three subcategories: Avoidant/Detached, Overcompensator, and Surrender. There is some similarity between these categories and the coping styles identified by Horney (1945) : moving away from, moving against, and moving toward others. However, there is not a perfect fit, and, as will be seen, there are some coping modes that do not fit clearly within any category system. Arntz et al. (2021) have recently suggested replacing the term Surrender with Resignation and Overcompensator with Inversion, however, the traditional terms will be used here.

First, a few other important concepts will be defined. The several modes or mode categories referred to will all be defined later. Emotion theory ( Greenberg and Pascual-Leone, 2006 ; Elliott and Greenberg, 2007 ) makes a distinction between primary and secondary emotion. A Child mode has, at its center, a primary emotion, such as anger at unfair treatment, sadness at loss or disappointment, or fear in the face of threat. Primary emotions are adaptive when based on accurate appraisal of a current situation, as they provide guides to action. However, when a current situation triggers a schema based on past memories, primary Child emotions are evoked out of proportion to the present reality. These are, in effect, flashbacks and are maladaptive. Secondary emotions, by contrast, result from coping with (and blocking) a distressing primary emotion and are usually maladaptive. Within the schema therapy framework this means they are part of a coping mode and are not associated with vulnerability.

Modes often follow each other in recognizable patterns or mode sequences ( Edwards, 2020 ). For example, a relationship conflict might activate a Vulnerable Child and an associated Parent mode . This might be followed by a switch to a coping mode such as Compliant Surrender or Avoidant Protector or Scolding Overcontroller , and this in turn might lead to a further mode. A client with bulimia nervosa who has been restricting her food intake ( Eating Disordered Overcontroller ) might experience intense craving and purchase a lot of food and eat it ( Detached Self-Soother ). After consuming it, she feels remorseful ( Shamed Child and Punitive Parent ) and determines to further restrict her food intake the next day ( Eating Disordered Overcontroller ). For a fuller example, see Edwards (2020) .

Modes that are relatively stable over time are referred to as default modes (e.g., Lobbestael, 2008 ). Individuals who spend a lot of time in default modes appear to have a relatively stable personality, but this is often an Overcompensator and not the Healthy Adult . Therapists can easily mistake a default mode for the Healthy Adult , especially when it is, for example, a Social Overcompensator or a Pollyanna Overcompensator . Therapists often need to help clients recognize that their default mode is a coping mode and not a fully adaptive way of being. By contrast, some dysregulated individuals display sudden shifts from one mode to another, referred to as mode flipping ( Kellogg and Young, 2006 ). This is often confusing and disconcerting for those with whom the individual is interacting.

The term Blended modes refers to the way that features of more than one mode may appear together at the same time ( Young et al., 2003 ). Blending is quite common and accounts for why, when we ask, “Which mode is the client in now?” the answer is not always straightforward. In the clinical literature authors often refer to child modes that blend separate distinctive experiences, for example, a Lonely Scared Child or an Abandoned-Abused Child . Blending is also common in coping modes: a Self-Aggrandizer often blends with a Paranoid Overcontoller , where self-righteousness and disdain are accompanied by a simultaneous wariness and suspiciousness. From this perspective, Simpson’s reference to “flavors” in the Helpless Surrenderer referred to above suggests how the mode can be blended with, for example, a Self-Pity Victim mode, or with a Complaining Protector or with a Defiant Child . Another common blended mode is found in those who seek to ward off abandonment by pleasing the other person ( Compliant Surrender ) and making things perfect for them ( Perfectionist Overcontroller ).

I introduce the term mode suites as an extension of the concept of blended modes, to refer to a set of modes with similar or overlapping features which may blend and/or sequence quite smoothly. As I suggest below, the Healthy Adult is not a single mode but a suite of modes in which individuals act maturely. However, there is also a suite of modes associated with narcissism, where the individual seamlessly sequences between and/or blends, for example, Self-Aggrandizer , Scolding Overcontroller , Bully and attack , Paranoid Overcontroller , and Complaining Protector in a single stream of interaction. The range of modes and characteristics that may sequence or blend in this way is illustrated by Day et al.’s (2020 ) qualitative study of the experiences of individuals with a narcissistic relative.

Backstage and frontstage: Roediger et al. (2018) and Roediger and Archonti (2020) use the metaphor of a theater in which some modes are “frontstage,” clear and visible, while others are less easy to see and can be thought of “backstage” or even “offstage.” A coping mode (frontstage), for example, blocks out a Child mode that is being coped with (backstage or offstage). Nevertheless, as Behary and Conway (2021) observe, clinicians may be able to detect the message from the backstage Child mode that is “hidden behind a wall of survival” and “got lost in delivery.”

Thus, the primary emotions of a Child mode can be channeled through a coping mode. This can happen through externalizing , or internalizing . In externalizing, for example, anger, with its source in a Child mode ( Angry Child, Defiant Child , or Enraged Child ), is channeled instrumentally toward others in a blaming and/or coercive manner through modes in which the aggression is a secondary emotion and is maladaptive ( Edwards, 2021 ). These Externalizing Overcompensators will be described later. The primary anger can also take an internalizing, route. It may be directed into self-attacking (see the Flagellating Overcontroller ). However, when combined with helplessness it becomes a muted embitterment that can be redirected toward the self, providing justification for the self-pity of the Self-Pity Victim mode, from where it may be further externalized in Complaining Protector . Or it may be redirected to keeping others out and resisting coercion, as in the Passive Resistor , or (with further externalizing added) in the Angry Protector .

A Comprehensive List of Schema Modes