Numbers, Facts and Trends Shaping Your World

Read our research on:

Full Topic List

Regions & Countries

- Publications

- Our Methods

- Short Reads

- Tools & Resources

Read Our Research On:

- Gen Z, Millennials Stand Out for Climate Change Activism, Social Media Engagement With Issue

- 3. Local impact of climate change, environmental problems

Table of Contents

- 1. Climate engagement and activism

- 2. Climate, energy and environmental policy

- Acknowledgments

- Methodology

- Appendix: Detailed charts and tables

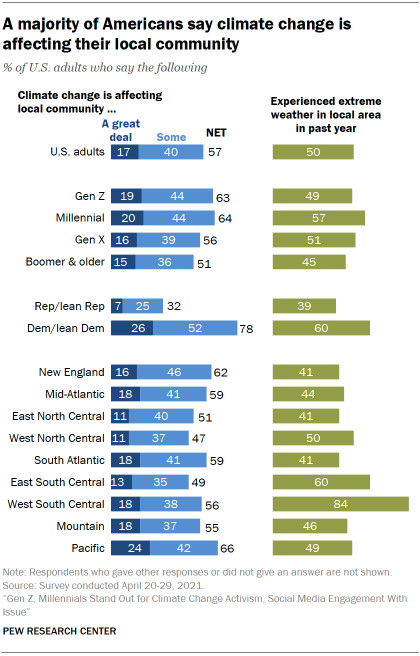

A majority of Americans say climate change is having at least some impact on their local community, and half say their area has experienced extreme weather over the past year, particularly those living in South Central states such as Texas and Alabama. On a related policy question, a large majority of Americans favor the idea of revising building standards so new construction can better withstand extreme weather events.

At the local level, experience with environmental problems – such as air and water pollution – varies across groups. Black and Hispanic adults are particularly likely to say they experience environmental problems in their local community, as are those with lower family incomes.

And when it comes to climate policy considerations, large majorities of Black and Hispanic adults – across income levels – say it’s very important to ensure that lower-income communities benefit from proposals aimed at reducing the effects of climate change.

More than half of U.S. adults say they have seen at least some local effects of climate change

Overall, 57% of U.S. adults say climate change is affecting their own community either a great deal (17%) or some (40%). Smaller shares say climate change is affecting their community not too much (27%) or not at all (15%).

Most Americans, including a majority of Republicans, say human activity plays at least some role in climate change

Most Americans (77%) say human activity contributes either a great deal (44%) or some (33%) to global climate change. Far fewer (22%) say human activities such as the burning of fossil fuels contribute not too much or not at all to climate change.

Republicans continue to be less likely to believe that human activity plays at least some part in global climate change. Still, 59% of this group says human activity contributes at least some, while 40% say human activity has not too much of a role or no role in climate change.

Democrats across generations are in broad agreement that human activity has at least some effect on climate change. Among Republicans, Gen Zers and Millennials are more likely than Gen X and Baby Boomer and older adults to see human activity as playing a role in global climate change. See the Appendix for details.

The overall share of Americans who say their area is affected a great deal by climate change is down 7 percentage points, from 24% a year ago to 17% today.

Americans’ beliefs about local impact of climate change are more closely linked to their partisanship than to where they live. Perceptions of local climate impact vary modestly across census regions. The regions that are relatively likely to say climate change is impacting their communities, such as New England and the Pacific, tend to be places that lean Democratic in their political affiliation. There are also modest differences by generation in beliefs about its local impact.

A separate question in the survey finds that half of Americans say their local area experienced an extreme weather event in the past 12 months.

A large majority (84%) in the West South Central region say they have experienced extreme weather in the last 12 months. The region was impacted by a severe winter storm in February that led to a power crisis in Texas. In contrast to the overall partisan differences seen on this question, comparable majorities of Republicans and Democrats in the West South Central region report their communities have experienced extreme weather in the past year.

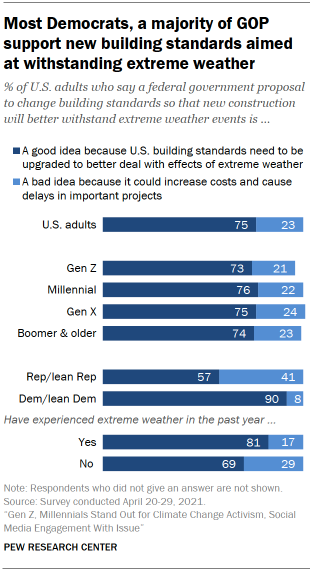

Wide public support for revised building standards to protect against extreme weather

Climate change is thought to be a key factor in the occurrence of more frequent and intense or extreme weather events. When asked about a federal government proposal to change building standards so that new construction will better withstand extreme weather events, 75% of U.S. adults responded in favor of this proposal, while 23% said it is a bad idea because it could increase costs and cause delays in important projects.

There is near consensus among Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents (90%) that revising building standards so construction better withstands extreme weather is a good idea. A 57% majority of Republicans and GOP leaners agree, although support is considerably higher among moderate and liberal Republicans (71%) than conservative Republicans (50%).

People who report direct experience with extreme weather in the past year are particularly likely to consider this a good idea (81% vs. 69% of those who do not report recent experience with extreme weather).

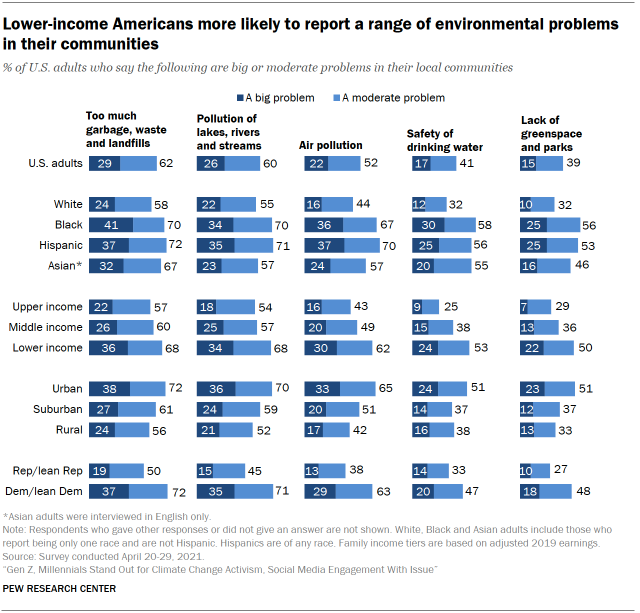

Black, Hispanic and lower-income adults more likely to report living in areas with big problems when it comes to air pollution, other environmental concerns

Overall, about six-in-ten Americans say they see at least moderate problems where they live when it comes to an excess of garbage (62%) and water pollution in lakes, rivers and streams (60%). About half (52%) say the same about local air pollution, and about four-in-ten say safe drinking water (41%) or a lack of greenspace (39%) are at least moderate problems.

Past research has found that Black, Hispanic and Asian American communities are more likely to be exposed to air pollution and other environmental hazards in their local area.

The Center survey finds Black and Hispanic adults particularly likely to say their local communities are having problems across this set of five environmental issues, and they stand out for the large share who consider these to be “big problems” where they live. About four-in-ten Black (41%) and Hispanic (37%) adults say the amount of garbage, waste and landfills in their community is a big problem. Black and Hispanic adults are also more likely than White adults to report that their community has big problems with air and water pollution, drinking water safety and a lack of greenspace and parks. A majority of Black (57%) and about half of Hispanic adults (53%) consider at least one of these five issues a big problem in their local area.

Lower-income Americans are also more likely to report that their area has big problems with these environmental issues. For example, about three-in-ten lower-income adults say their local community has a big problem with air pollution. About half as many upper-income adults (16%) say the same about their community. Half of those with lower family incomes say their local communities are having a big problem with at least one of these five environmental issues.

The Biden administration has brought a new focus to environmental justice concerns underlying climate and energy policy. Biden has called for $1.4 billion in his recent budget proposal for initiatives aimed at helping communities address racial, ethnic and income inequalities in pollution and other environmental hazards.

As Americans think about proposals to address climate change, Black (68%) and Hispanic adults (55%) stand out for the high shares who say it is very important to them that such proposals help lower-income communities.

More than half of lower-income Americans (54%) say this is very important to them, compared with 36% of upper-income adults.

Middle- and upper-income Black adults (70%) are about as likely as lower-income Black adults (66%) to say this is very important to them, however. Similarly, there are no differences on this question between middle/upper income Hispanic adults and those with lower incomes (54% vs. 57%, respectively).

A majority of Democrats and independents who lean toward the Democratic Party (59%) say it is very important to them that climate change proposals help lower-income communities; far fewer Republicans and Republican leaners (27%) say this.

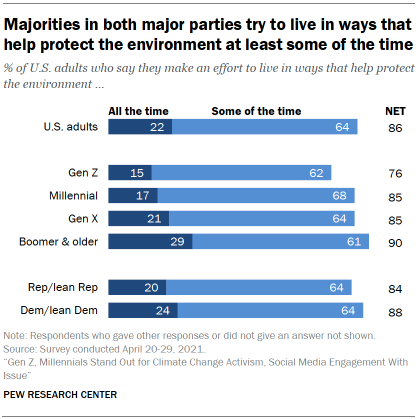

Older Americans are more likely to say they regularly try to live in ways that help the environment

A large majority of Americans (86%) say they try to live in ways that help protect the environment all the time (22%) or some of the time (64%). Just 14% say they never or rarely make such an effort. These findings are largely unchanged since the question was last asked in October 2019 .

In contrast to views and behaviors related to climate change, Baby Boomer and older adults are more likely than those in younger generations to say they try to live in environmentally conscious ways all the time (29%, vs. 21% in Gen X, 16% of Millennials and 15% in Gen Z).

And, unlike views on many policy issues related to the environment, similar shares of Democrats (88%) and Republicans (84%) say they make an effort to do this at least some of the time.

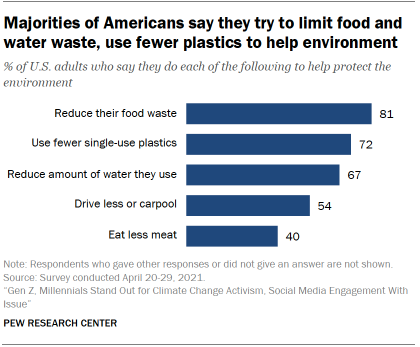

Majorities of U.S. adults say they take some everyday actions in order to help protect the environment, including reducing their food waste (81%), using fewer plastics that cannot be reused such as plastic bags, straws or cups (72%) or reducing the amount of water they use (67%). More than half of Americans (54%) say they drive less or carpool to help the environment, and 40% say they eat less meat.

About one-in-five adults (18%) say they do all five of these activities to help the environment, a similar share to when these questions were last asked in October 2019. On average, Americans do 3.3 of these activities.

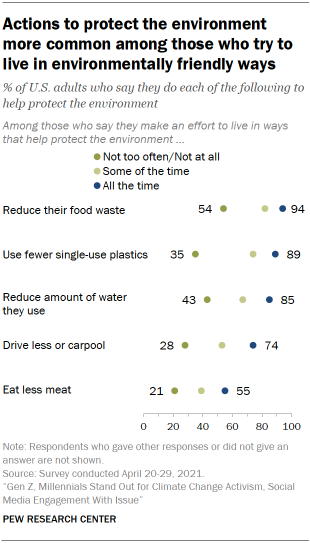

People who say they try to be environmentally conscious all the time are much more likely to say they are doing specific things to protect the environment. For instance, a large majority (89%) of people who make an effort to live in ways that help protect the environment all the time say they use fewer single-use plastics such as bags and straws in order to protect the environment. This compares with 35% of those who say they do not or don’t often make an effort to protect the environment.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter

Fresh data delivery Saturday mornings

Sign up for The Briefing

Weekly updates on the world of news & information

- Baby Boomers

- Climate, Energy & Environment

- Generation X

- Generation Z

- Generations, Age & Politics

- Millennials

- Politics Online

- Silent Generation

- Social Media & the News

Boomers, Silents still have most seats in Congress, though number of Millennials, Gen Xers is up slightly

The pace of boomer retirements has accelerated in the past year, u.s. millennials tend to have favorable views of foreign countries and institutions – even as they age, millennials overtake baby boomers as america’s largest generation, older americans continue to follow covid-19 news more closely than younger adults, most popular, report materials.

- American Trends Panel Wave 89

1615 L St. NW, Suite 800 Washington, DC 20036 USA (+1) 202-419-4300 | Main (+1) 202-857-8562 | Fax (+1) 202-419-4372 | Media Inquiries

Research Topics

- Age & Generations

- Coronavirus (COVID-19)

- Economy & Work

- Family & Relationships

- Gender & LGBTQ

- Immigration & Migration

- International Affairs

- Internet & Technology

- Methodological Research

- News Habits & Media

- Non-U.S. Governments

- Other Topics

- Politics & Policy

- Race & Ethnicity

- Email Newsletters

ABOUT PEW RESEARCH CENTER Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

Copyright 2024 Pew Research Center

Terms & Conditions

Privacy Policy

Cookie Settings

Reprints, Permissions & Use Policy

- Open access

- Published: 24 September 2021

A community-engaged approach to understanding environmental health concerns and solutions in urban and rural communities

- Suwei Wang 1 , 2 ,

- Molly B. Richardson 3 ,

- Mary B. Evans 4 ,

- Ethel Johnson 5 ,

- Sheryl Threadgill-Matthews 5 ,

- Sheila Tyson 6 ,

- Katherine L. White 4 &

- Julia M. Gohlke 2

BMC Public Health volume 21 , Article number: 1738 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

1356 Accesses

1 Citations

Metrics details

Focus groups and workshops can be used to gain insights into the persistence of and potential solutions for environmental health priorities in underserved areas. The objective of this study was to characterize focus group and workshop outcomes of a community-academic partnership focused on addressing environmental health priorities in an urban and a rural location in Alabama between 2012 and 2019.

Six focus groups were conducted in 2016 with 60 participants from the City of Birmingham (urban) and 51 participants from Wilcox County (rural), Alabama to discuss solutions for identified environmental health priorities based on previous focus group results in 2012. Recorded focus groups were transcribed and analyzed using the grounded theory approach. Four follow-up workshops that included written survey instruments were conducted to further explore identified priorities and determine whether the priorities change over time in the same urban (68 participants) and rural (72 participants) locations in 2018 and 2019.

Consistent with focus groups in 2012, all six focus groups in 2016 in Birmingham identified abandoned houses as the primary environmental priority. Four groups listed attending city council meetings, contacting government agencies and reporting issues as individual-level solutions. Identified city-level solutions included city-led confiscation, tearing down and transferring of abandoned property ownership. In Wilcox County, all six groups agreed the top priority was drinking water quality, consistent with results in 2012. While the priority was different in Birmingham versus Wilcox County, the top identified reason for problem persistence was similar, namely unresponsive authorities. Additionally, individual-level solutions identified by Wilcox County focus groups were similar to Birmingham, including contacting and pressuring agencies and developing petitions and protesting to raise awareness, while local policy-level solutions identified in Wilcox County included government-led provision of grants to improve septic systems, and transparency in allocation of funds. Workshops in 2018 and 2019 further emphasized water quality as the top priority in Wilcox County, while participants in Birmingham transitioned from abandoned houses as a top priority in 2018 to drinking water quality as a new priority in 2019.

Conclusions

Applying a community-engaged approach in both urban and rural locations provided better understanding of the unique opportunities and challenges for identifying potential interventions for environmental health priorities in both locations. Results can help inform future efforts to address locally defined environmental health issues and solutions.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

A healthy environment is essential for improving the quality of life and the extent of healthy living. Worldwide, preventable environmental factors are responsible for 23% of all deaths and 26% of deaths among children less than 5 years old [ 1 ]. Environmental factors are diverse with far-reaching impacts on health [ 2 ]. Community engaged research in environmental health includes a variety of non-academic stakeholders, such as residents in affected neighborhoods, neighborhood leaders, non-governmental agencies, and government agency representation. It is designed to improve our understanding of environmental factors affecting health that may be the most promising to address based on local priorities and circumstances.

Focus groups are one of the methods for facilitating community-engaged research. It is an invaluable tool for researchers investigating community’s perceptions of environmental hazards, because they provide a setting for gathering resident’s knowledge and establishes common ground among participants and between participants and researchers [ 3 ]. Local focus groups can engage residents and identify ways to work towards solving a problem collaboratively [ 4 ]. Because of the small size and informal nature of focus groups, participants can build on and debate each other’s responses, which helps to better understand an issue and the influences surrounding it [ 5 ]. This understanding and information are obtained in a relatively short amount of time, so focus groups are an efficient way for researchers to attain information [ 6 ]. Furthermore, focus groups can enlighten researchers to perceived environmental hazards not previously considered [ 3 ]. All of these attributes are essential for developing a feasible, acceptable, and supported intervention to address health outcomes associated with environmental factors [ 7 ].

In 2010 we initiated a community-academic partnership, ENACT, between Friends of West End (FoWE) in Birmingham, Alabama (AL), and West Central Alabama Community Health Improvement League (WCACHIL) in Wilcox County, AL and Virginia Tech, University of Alabama at Birmingham, and Johns Hopkins University [ 8 ]. Through ENACT we work on environmental health issues in Alabama with successful completion of several environmental epidemiology studies, focus groups, workshops, and phone surveys [ 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 ]. In our initial focus groups in 2012, we found that abandoned houses was the highest environmental health priority in Birmingham, Alabama while inadequate sewer and water services was the top priority in Wilcox County, Alabama [ 9 ]. A follow-up larger scale and randomly sampled phone survey reaffirmed these priorities in each community and furthered our understanding of how resident priorities are similar or different from local health agency priorities [ 11 ]. Additionally, follow-up community-engaged research allows the dissemination of updated results and collection of new information to verify previous results and further refine the most appropriate path to mitigate health outcomes associated with environmental health priorities.

Water and sewage service issues and abandoned houses and lots are significant environmental health problems in rural and urban areas in the United States, respectively. Unsewered homes are common in rural areas of the United States, leading to increased risk of a variety of infectious diseases [ 15 ]. For example, soil transmitted helminth infections were identified in household members without adequate sewage in rural Alabama [ 16 ]. Drinking water service characteristics have also been associated with reported gastrointestinal illness in rural Alabama [ 17 ]. Garvin et al. (2013) found abandoned properties affect community well-being via overshadowing positive aspects of community, producing fractures between neighbors, attracting crime, and making residents fearful [ 18 ]. Other research found the problem is perceived as particularly widespread in the U.S. South, where our study areas are located [ 19 ]. Abandoned houses and lots can contribute to numerous health and safety hazards including falling debris, vermin, mold, standing water, toxic chemicals, and sharp rusty objects [ 20 ], and can have negative impacts on housing/neighborhood vitality, violence and crime prevention efforts, fire and vandalism risk, commercial district vitality, and assessed property values, etc. [ 19 , 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 ].

In the present study, we build from our previous findings to 1) better understand why those problems persist, 2) what residents feel the solution is, and who is responsible for enacting the solution 3) identify ways to support residents in identifying a process to address environmental concerns and 4) examine whether environmental health priorities change over time. Applying this community-engaged approach in both an urban and a rural location allowed us to better understand the unique opportunities and challenges in both locations.

Characteristics of focus group study populations

Birmingham, AL is the largest city in Alabama with a population of 209,403, of which 70.5% of the population identifies as Black or African American [ 25 ]. Birmingham has a poverty rate of 27.2%, and those identifying as Black or African American comprise 76.9% of those living in poverty [ 25 ]. Wilcox County, AL, a rural setting, has a lower population of 10,300, of which 71.3% identify as Black or African American [ 25 ]. A total of 33.4% of the population in Wilcox County live in poverty and of that 88.2% identify as Black or African American [ 25 ].

Focus group procedure

This study involved Virginia Tech and University of Alabama at Birmingham researchers collaborating with Friends of West End (FoWE) in Birmingham, AL, and West Central Alabama Community Health Improvement League (WCACHIL) in Wilcox County, AL as part of an ongoing community-academic partnership, ENACT [ 8 ]. The protocol was approved by the Virginia Tech Institutional Review Board (15–761). The community partners recruited participants aged at least 18 without regard to sex, ethnicity or ancestry. WCACHIL recruited 51 participants in Wilcox County and FoWE recruited 60 participants in Birmingham using a convenience and snowball sampling approach. The number of focus groups ( N = 12, 6 in Birmingham city, AL and 6 in Wilcox County, AL) was based on the need to expand our line of questions from our previous focus groups investigating environmental health priorities in 2012 ( N = 8 in total, 4 in Birmingham, AL and 4 in Wilcox County, AL) [ 9 ]. This new direction led us to include two more focus groups in each location, and this number of focus groups is consistent with previous studies exploring data saturation across a wide range of topics [ 26 , 27 , 28 , 29 ].

Community and academic partners together drafted and agreed upon a guide of questions to ensure appropriateness and consistency between groups. The guide followed a natural progression of identifying positive attributes of participants’ neighborhoods, determining whether previously identified environmental health priorities (abandoned houses and overgrown lots in Birmingham and drinking water access and quality in Wilcox County) [ 9 ] were still priority issues, why the problems persisted, who was responsible for solving them, and what participants felt were the solutions to address those priority issues.

We took a positivist approach in focus group data collection and analysis. The facilitator guide (Additional file 1 ) emphasized encouraging all participants to contribute, embracing new ideas, and enforcing respect for all participants’ comments [ 30 ]. Members of the community-academic partnership served as facilitators in each group. Facilitators were encouraged to utilize strong listening and questioning skills, prodding participants with prompts to encourage them to speak up or clarify statements. All facilitators had training in the value of focus groups and the best practices for facilitating focus groups that are partly based on works by Franz et al., Drake et al. [ 31 , 32 ] . Facilitators aimed to document subjects opinions and attitudes in an objective way, assuming a detached, independent role in the discussion, but ensuring focus groups followed the structured guide [ 33 ]. Facilitators were provided guidance and practice on how to draw out concerns while not bringing bias by sharing their own views [ 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 ], drawing adequate participation from each participant, and minimizing the influence of dominant speaker(s) views. In training and planning for focus groups, we placed emphasis on the importance of the role of the facilitator, having groups be of reasonable size (8–10 individuals), and individuals not being too familiar with other group members [ 33 ].

Twelve focus groups were conducted in September 2016, six in Birmingham and six in Wilcox County. Focus groups were organized to be at a time when participants would be available and within familiar neighborhood gathering places to increase comfort in active participation. Approximately 10 participants sat at each table with facilitators. Facilitators went through formal Institutional Review Board consent, then initiated recording of the focus group with digital recorders. Focus groups lasted approximately one-hour and participants completed a written survey. Facilitators’ field notes were considered during the coding process, described below.

Focus group data analysis

Researchers do not editorialize participants’ opinions and remained non-judgmental and respectful [ 37 ]. Recordings were transcribed by the second author. In the first stage, transcriptions were coded into categories based on questions posed (determined a priori) from the script independently by second author and third author (Additional file 2 ). The second author then went through all coded transcripts combining responses identified to be most inclusive [ 38 ]. In the event that a statement responded to multiple questions (i.e., responsible parties and solutions), they were coded to each question response. In the next stage, the second author and third/seventh author independently further subcategorized the inclusive coded transcripts per the subcategorization coding tree (Additional file 2 ). Summaries were then consolidated and presented by focus group and by location with verbatim. Recordings from all focus groups were analyzed and coded to ensure all themes discussed are presented in the results. Interrater reliability was assessed for topics: reasons for persistence, responsible parties, sources of trusted information, and other priorities brought up. Interrater reliability rate (IRR) was high in both Wilcox County transcripts and Birmingham transcripts (IRR = 90.6% in Wilcox County, 91.9% in Birmingham). An IRR of 90.6% reflects that 512 out of 563 responses were categorized the same between the two coders.

Follow-up workshops

Preliminary results from the focus groups were compiled and used to develop a survey instrument to further explore environmental health priorities and solutions and implemented at workshops in May 2018. Fifty-three participants from the same urban and rural locations (23 in Birmingham and 30 in Wilcox County) attended the workshops and completed the survey. A total of 92 participants from the same urban and rural locations (49 in Birmingham and 43 in Wilcox County) attended another two follow-up workshops in September 2019. A collaborative presentation by researchers and community partners on spatially explicit risk maps developed from our retrospective analysis of adverse health outcomes associated with heatwaves in Alabama was given. Participants filled out a written survey ranking the most concerning environmental health issues. Demographic information was also collected in the survey instruments administered in 2018 and 2019. The agendas for the workshops are shown in Additional file 1 . All survey instruments are accessible at our research outreach website [ 39 , 40 ].

Answers to the surveys were summarized and compared between Birmingham and Wilcox County participants in 2018 and 2019, respectively. The responses to open-ended questions were first coded into categories by the first author, then independently coded by the eighth author using the categories established by the first author. Any differences were discussed to resolve final categorization. The rankings of six environmental health issues were converted to Likert scale, with average ranks computed for ties. For a specific environmental health issue, the Mann-Whitney test was used to determine whether the medians of the ranks were different in Birmingham vs. Wilcox County.

Study population

Most participants in the 2016 focus groups (92%) and 2018 (98%) and 2019 (86%) workshops self-identified as Black or African American (Table 1 ). In 2016 focus groups, urban and rural participants had similar gender ratio (67, 80% female, respectively), education level (48, 53% with higher than high school diploma, respectively), annual household income (68, 55% at <$ 20,000, respectively), and general health (92, 90% responding in good health condition, respectively) while urban participants were older compared to rural participants (mean age 60 in urban vs. 52 in rural, p -value 7.9E-03). In 2018 workshops, the only urban-rural difference among participants was that a higher percent of rural participants participated in the 2016 focus groups (63% in rural vs. 26% in urban, p -value 0.02). In 2019 workshops, urban participants were younger (mean age 50 in urban vs. 58 in rural, p -value 0.02), had a lower percent in annual household income ≥$20,000 (42% in urban vs. 76% in rural, p- value 1.6E-04), a lower percent in participation of 2017 monitor study (16% in urban vs. 60% in rural, p -value 3.4E-05) and a lower percent in participation of 2016 focus groups (18% in urban vs. 62% in rural, p -value 8.8E-05) (Table 1 ).

Environmental health priorities and responsible parties identified in 2016 focus groups

A total of 83% participants in Birmingham and 12% participants in Wilcox County believed urban areas had worse environmental problems than rural areas ( p- value 6.3E-13). Most participants (88% participants in Birmingham and 84% participants in Wilcox County, p-value 0.56) believed their communities did not receive its fair share of state and local resources devoted to environmental health problems.

Table 2 reports the environmental priority findings in the six focus groups in Birmingham. All six groups agreed that the main priority was abandoned and unmaintained houses: “ All you have to do is ride through to see. It is a disgrace. Just driving through it’s so grown up (overgrown) that you can’t even see the house. ” Groups mentioned many health concerns they believed were exacerbated by abandoned housing and overgrown lots including general health (2 groups), carbon monoxide, cough, mold, and infectious diseases (1 group). For the reason(s) this issue persists, five groups brought up that authorities were unresponsive or they did not follow through, four groups discussed government maintenance was limited and slow, and four groups believed money was an issue. “ We’ve been going on 15 years trying to get something going with our councilor. You couldn’t get nothing. ” Five groups identified Birmingham City Council as the top responsible party. Solutions were proposed by participants. More individuals attending city county meetings (4 groups), contacting government agencies and reporting issues (4 groups), and asking for government patrol of abandoned houses and additional maintenance of properties (3 groups) were top suggested short-term solutions. For long-term solutions, ideas included greater participation in community and neighborhood meetings (2 groups): “(You) Gotta go out there and see. And if you don’t go out there and participate then you’ll never see. ”, buy or mortgage abandoned houses/lots (2 groups), community hold authorities accountable (2 groups), and government confiscates, tears down (5 groups) and transfer the ownership of abandoned houses for better maintenance (4 groups).

Table 3 reports the results in the six focus groups in Wilcox County. In Wilcox County, the focus groups focused on the priority issue of drinking water access and quality with some discussion on sewage and septic issues. All six groups were concerned about the smell, look and taste of water. Five groups were concerned about the lack of water access and water-borne diseases. Primary health concerns that arose in discussion included cancer (5 groups), obesity (1 group), and infectious agents associated with poor sanitation (1 group). “ And it’s just awful. It’s awful because it makes your yard smell. It makes everything smell like septic. ” Four groups believed this issue has persisted because of unresponsiveness from authorities, particularly the county commissioners, and three groups suggested the lack of knowledge, information, and resources led to problem persistence. As for individual level solutions, participants suggested pressuring and reaching out to local government representatives (5 groups), attending county commission meetings and water board meetings (4 groups), and avoiding the use of county water (e.g., use bottled water) (2 groups). At the neighborhood level, participants mentioned organizing petitions and protesting would raise awareness (5 groups) and building trust, uniting, and engaging communities and organizing community meetings (3 groups). At the government level, they saw providing grants for installation and improvement of septic systems (5 groups) as well as testing water and distributing findings (3 groups), as important next steps to solve this issue.

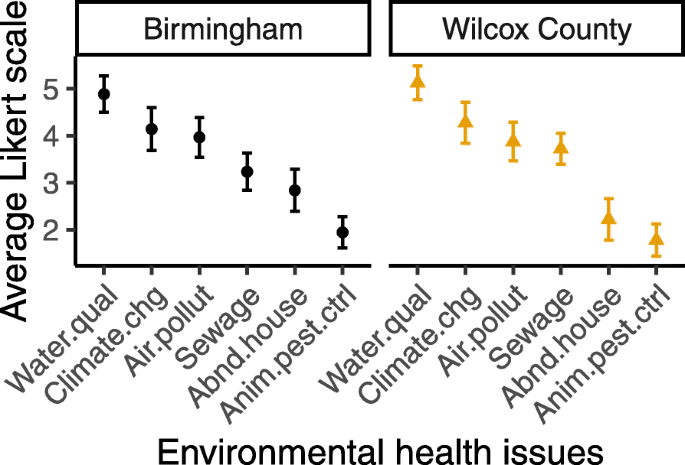

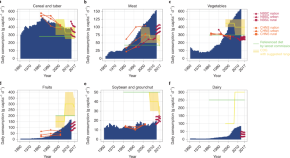

Environmental health priorities change over time

Compared to our initial focus groups in 2012 [ 9 ] and our follow-up phone surveys in 2016 [ 11 ], and finally our focus groups in 2016 and workshops in 2018 and 2019 described herein, environmental health priorities changed over time in Birmingham, but stayed consistent in Wilcox County. In the follow-up workshops in 2018, 16 (70%) of participants in Birmingham agreed that abandoned housing was the primary environmental health priority while 21 (70%) of participants in Wilcox County agreed that drinking water and wastewater issues was the primary environmental health priority (Tables 4 - 5 ). However, in the 2019 follow-up workshops, participants from both locations ranked water quality as the No.1 environmental health priority (Fig. 1 ). Based on the median ranks, Wilcox participants ranked sewage and septic systems a higher priority compared with Birmingham participants (4.0 in Wilcox vs. 3.0 in Birmingham, Mann-Whitney test p -value 0.049) while they ranked abandoned houses/lots a lower priority (2.0 in Wilcox vs. 3.0 in Birmingham, Mann-Whitney test p- value 0.046).

Mean Likert scale for environmental health issues in 2019 workshops. 95% confidence intervals were shown. Water.qual = water quality, climate.chg = climate change, Air.pollut = air pollution, Sewage = sewage and septic, Abnd.house = abandoned houses and lots, Anim.pest.ctrl = animal and pest control

In the 2018 follow-up workshops, more than half of the participants believed state and local resources were not fairly distributed to communities to address environmental health problems (87% in Birmingham and 67% in Wilcox, p- value 0.59), and both communities suggested a lack of leadership at the local level was the top reason behind this unfair distribution. In these workshops, Birmingham participants built from the 2016 focus group results described above, stating they would like to see neighborhood leaders attend city council meetings and report back to neighborhood residents (48% participants), and communicate progress, plans and timelines on addressing abandoned housing and vacant lots in their neighborhoods (22% participants). Birmingham participants stated that more state and local government resources should be devoted to hiring more work crews to tear down abandoned houses, mow overgrown lots (61% participants), provide incentives to build new business or new homes (26% participants), and provide more police presence (22% participants). Wilcox county participants in the 2018 follow-up workshops suggested community leaders should write grant proposals for money to fix the septic issues (50% participants) and hold local meetings to inform and unite residents (33% participants). They would also like to see state and local governing officials put more resources towards water lines, wells, and wastewater treatment (50% participants), and evaluate whether the pipes are safe or need to be replaced (37% participants) (Tables 4 - 5 ).

Sources of trusted information

The most trusted sources of information were news on television (TV), city council and city council representatives, and word-of-mouth in Birmingham, all of which were mentioned by four focus groups. Radio (5 groups), news on TV (4 groups), and word-of-mouth (3 groups) were the most trusted source of information in Wilcox County. One group in Wilcox County reported trust in local government, but not the county commission or mayor. In contrast, Birmingham focus groups frequently cited the government as a trusted source of information, in particular their city council and city council representative. Of the two Birmingham focus groups that did not cite the government as a trusted source of information, one did not mention any sources of trusted information and the other only cited the news and newspaper. While the Birmingham focus groups never mentioned distrusted sources of information, one group did say there was a lack of a trusted source of information. Similar to 2016 focus group results, in the 2018 follow-up workshops, Birmingham survey participants identified TV, city council meetings and neighborhood meetings, and conversations with community leaders as the most trusted information sources, while Wilcox County participants identified TV, radio, and county commission meetings as the most trusted information sources (Tables 4 - 5 ).

The ENACT community-academic partnership has been engaging with residents in Birmingham AL and Wilcox County AL since 2010 to understand environmental health priorities through focus groups, phone surveys, written surveys and workshops [ 9 , 11 ]. Here we present results from our most recent focus groups and workshops that clarified priorities, possible solutions, responsibly parties, and sources of trusted information on priority issues. We found that the environmental health priorities of abandoned houses in Birmingham and drinking water issues in Wilcox County in the focus groups were consistent with our previous findings [ 9 ].

The results suggest that participants saw local government non-responsiveness as the top reason for issues with abandoned housing persisting (5 of 6 focus groups), while also acknowledging government actions as the most promising solutions in addressing the abandoned housing issue in Birmingham (Table 2 ). In the 2018 workshops, 39% participants in Birmingham reported they believed local government (city, mayor, city councils) were most responsible for getting rid of abandoned houses (Table 4 ), showing consistency over time. In Wilcox County, five out of six focus groups discussed a range of solutions at the individual level, community level and government levels, which suggests that participants in Wilcox County see involving all stakeholders to tackle the water and sanitation problems is most promising.

The results, together with identified persistence reasons and potential solutions at the individual, community, and government levels may serve as evidence-based tools for identifying actions in the future. Follow-up workshops not only provided the opportunity to examine whether the identified environmental health priorities change over time but also serve as the events where research results were disseminated back to residents. As environmental health is a dynamic and evolving field, the environmental issues in Birmingham and Wilcox County communities can change over time. For example, Birmingham City Council programs initiated between 2016 and 2019 [ 41 , 42 ] could have contributed to reducing residents’ concerns over abandoned housing and vacant lots in 2019. Alternatively, the number of Public Water Systems with any violation dropped from 117 in 2013, to 61 in 2018, to 110 in year 2020 in Alabama [ 43 ], suggesting water quality issues have not changed.

Knowing from what sources people get trusted information on environmental health issues can shed light on why people are concerned about particular risks. Results showed that both communities trusted news on TV and word-of-mouth, and Birmingham groups trusted city council and Wilcox groups trusted radio programs. We also found a lack of trust in government in Wilcox groups. The results are consistent with a similar study surveying rural residents in El Paso, Texas where 54 and 46% participants had high confidence in television and radio, respectively, and the participants had low confidence in the government as a source of information [ 44 ]. As suggested by Byrd et al. (1997), the way that risk is portrayed by the media and the selection of stories may impact people’s perception of environmental health priorities [ 44 ]. Knowing the trusted information source may help community leaders monitor emerging or ongoing environmental health priority topics as well as use these sources to involve more residents, spread updates of meetings and policies, and disseminate evidence-based solutions. The names of specific TV programs or radios stations where participants get trusted information can be collected in future studies.

There are some limitations in the study. Bias may have been introduced with the use of nonprobability sampling methods to recruit focus group and workshop participants; however similar participant demographics in Birmingham and Wilcox County reduced potential bias when comparing results between the two locations, as studies have shown that gender, race, and culture are primary influences on risk perception [ 45 ]. As is common in health studies [ 46 ], the results presented herein reflect higher participation rates of women in both Birmingham and Wilcox County events, therefore male perspectives, if different, are underrepresented. Focus group participants may have refrained from bringing up issues in front of other community members or respected community leaders. However, in the focus group setting, participants could add to others’ responses to clarify issues and direct discussion in a meaningful way. Participants may also feel empowered by voicing their opinions and insights with other residents. There were some technical challenges in understanding some of the audio recordings, specifically distinguishing individual speakers within the group. This technical challenge coupled with high agreement within each group led to group-wise comparisons instead of individual counts as reported in previous focus groups [ 9 ]. As noted in the methods, the coding groups were not mutually exclusive, and topics could be counted multiple times, which is common to focus group analysis methodologies [ 38 ]. There was a higher percent of returning participants in Wilcox compared to Birmingham, which may have contributed to the result that drinking water quality was consistently the number one environmental priority in Wilcox County, however we do note that a randomly sampled phone survey we conducted also identified water quality as a top priority [ 11 ] .

Focus groups conducted in 2016 reaffirmed the identified environmental health priorities in 2012 focus groups, in both urban and rural communities. The top environmental health priority remained water quality and sewage treatment in the rural community in 2018 and 2019 surveys but switched from abandoned houses to water quality in the urban community in 2019. Participants identified ways to support the community in identifying and enacting solutions to their environmental concerns, which can be useful for community leaders to make future changes to address the problems.

Availability of data and materials

The dataset generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to the identifiable audio recordings, identifiable demographic information and questionnaires from participants. De-identified and aggregated data can be obtained by request to the corresponding author, Julia Gohlke, at [email protected] .

Abbreviations

Friends of West End

West Central Alabama Community Health Improvement League

Interrater reliability rate

Prüss-Üstün A, Wolf J, Corvalán C, Bos R, Neira M. Preventing disease through healthy environments: a global assessment of the burden of disease from environmental risks: World Health Organization; 2016.

Google Scholar

HealthyPeople.gov . Environmental Health [Available from: https://www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives/topic/environmental-health#one .

Green L, Fullilove M, Evans D, Shepard P. “ Hey, mom, thanks!”: use of focus groups in the development of place-specific materials for a community environmental action campaign. Environ Health Perspect. 2002;110(suppl 2):265–9. https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.02110s2265 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Cantu A, Graham MA, Millard AV, Flores I, Mugleston MK, Reyes IY, et al. Environmental justice and community-based research in Texas borderland Colonias. Public Health Nurs. 2016;33(1):65–72. https://doi.org/10.1111/phn.12187 .

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Tausch AP, Menold N. Methodological aspects of focus groups in health research: results of qualitative interviews with focus group moderators. Glob Qual Nurs Res. 2016;3:2333393616630466.

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Gill P, Stewart K, Treasure E, Chadwick B. Methods of data collection in qualitative research: interviews and focus groups. Br Dent J. 2008;204(6):291–5. https://doi.org/10.1038/bdj.2008.192 .

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Baruth M, Wilcox S, Laken M, Bopp M, Saunders R. Implementation of a faith-based physical activity intervention: insights from church health directors. J Community Health. 2008;33(5):304–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-008-9098-4 .

ENACT. ENACT Organization [Available from: https://www.enactalabama.org/ .

Bernhard M, Evans M, Kent S, Johnson E, Threadgill S, Tyson S, et al. Identifying environmental health priorities in underserved populations: a study of rural versus urban communities. Public Health. 2013;127(11):994–1004. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2013.08.005 .

Bernhard MC, Kent ST, Sloan ME, Evans MB, McClure LA, Gohlke JM. Measuring personal heat exposure in an urban and rural environment. Environ Res. 2015;137:410–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envres.2014.11.002 .

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Wu CY, Evans MB, Wolff PE, Gohlke JM. Environmental health priorities of residents and environmental health professionals: implications for improving environmental health services in rural versus urban communities. J Environ Health. 2017;80(5):28–36.

Richardson MB, Chmielewski C, Wu CYH, Evans MB, McClure LA, Hosig KW, et al. The effect of time spent outdoors during summer on daily blood glucose and steps in women with type 2 diabetes. J Behav Med. 2020;43(5):783–90. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-019-00113-5 .

Wang S, Richardson MB, Wu CY, Cholewa CD, Lungu CT, Zaitchik BF, et al. Estimating occupational heat exposure from personal sampling of public works employees in Birmingham, Alabama. J Occup Environ Med. 2019;61(6):518–24. https://doi.org/10.1097/JOM.0000000000001604 .

Wang S, Richardson M, Wu CYH, Zaitchik BF, Gohlke JM. Characterization of Heat Index Experienced by Individuals Residing in Urban and Rural settings. [Unpublished work]. In press 2020.

Maxcy-Brown J, Elliott MA, Krometis LA, White KD, Brown J, Lall U. Making waves: right in our backyard-surface discharge of untreated wastewater from homes in the United States. Water Res. 2020;116647:116647. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.watres.2020.116647 .

Article CAS Google Scholar

McKenna ML, McAtee S, Bryan PE, Jeun R, Ward T, Kraus J, et al. Human intestinal parasite burden and poor sanitation in rural Alabama. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2017;97(5):1623–8. https://doi.org/10.4269/ajtmh.17-0396 .

Stauber CE, Wedgworth JC, Johnson P, Olson JB, Ayers T, Elliott M, et al. Associations between self-reported gastrointestinal illness and water system characteristics in community water supplies in rural Alabama: a cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2016;11(1):e0148102. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0148102 .

Garvin E, Branas C, Keddem S, Sellman J, Cannuscio C. More than just an eyesore: local insights and solutions on vacant land and urban health. J Urban Health. 2013;90(3):412–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-012-9782-7 .

Accordino J, Johnson GT. Addressing the vacant and abandoned property problem. J Urban Aff. 2000;22(3):301–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/0735-2166.00058 .

Article Google Scholar

Purtle J. How abandoned buildings could make you sick 2012 [Available from: https://www.inquirer.com/philly/blogs/public_health/Recklessly-abandoned-Phillys-neglected-buildings-might-affect-our-health-in-more-ways-than-one.html .

Spellman W. Abandoned buildings: magnets for crime? J Crim Just. 1993;21(5):481–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/0047-2352(93)90033-J .

Fahy R, Norton A. How being poor affects fire risks. Fire J (Boston, MA). 1989;83(1):29–36.

Skarbek J. Vacant structures: the sleeping dragons. Fire Eng. 1989;142:34–8.

Branas CC, Rubin D, Guo W. Vacant properties and violence in neighborhoods. Int Scholarly Res Notices. 2012;2012. https://downloads.hindawi.com/archive/2012/246142.pdf .

US-Census-Bureau. US Census Bureau quick facts: Birmingham AL and Wilcox county 2017 [Available from: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/birminghamcityalabama,wilcoxcountyalabama,US/PST045219 .

Morgan MG, Fischhoff B, Bostrom A, Atman CJ. Risk communication: a mental models approach: Cambridge University press; 2002. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511814679 .

Book Google Scholar

Guest G, Bunce A, Johnson L. How many interviews are enough? An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods. 2006;18(1):59–82. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X05279903 .

Guest G, Namey E, McKenna K. How many focus groups are enough? Building an evidence base for nonprobability sample sizes. Field Methods. 2017;29(1):3–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X16639015 .

Francis JJ, Johnston M, Robertson C, Glidewell L, Entwistle V, Eccles MP, et al. What is an adequate sample size? Operationalising data saturation for theory-based interview studies. Psychol Health. 2010;25(10):1229–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870440903194015 .

Teufel-Shone NI, Williams S. Focus groups in small communities. Prev Chronic Dis. 2010;7(3):A67. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2879999/ .

Franz NK. The unfocused focus group: benefit or bane? Qual Rep. 2011;16(5):1380.

Jervis MG, Drake M. The use of qualitative research methods in quantitative science: a review. J Sens Stud. 2014;29(4):234–47. https://doi.org/10.1111/joss.12101 .

Coule T. Theories of knowledge and focus groups in organization and management research. Qualitative Research in Organizations and Management: An International Journal; 2013.

Krueger RA. Moderating focus groups: sage publications; 1997. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781483328133 .

Krueger RA, Casey MA. Designing and conducting focus group interviews. Citeseer; 2002.

Knodel J. The design and analysis of focus group studies: a practical approach. In: Successful focus groups: Advancing the state of the art, vol. 1; 1993. p. 35–50. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781483349008.n3 .

Chapter Google Scholar

Duvall SH, Laura; Ike, Brooke; Martin, Mariah; Roach, Claire; Streichert, Laura. Focus Groups in Action: A Practical Guide University of Washington [Available from: https://www.slideserve.com/presley/focus-groups-in-action-a-practical-guide .

Campbell JL, Quincy C, Osserman J, Pedersen OK. Coding in-depth semistructured interviews: problems of unitization and intercoder reliability and agreement. Sociol Methods Res. 2013;42(3):294–320. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124113500475 .

ENACT. Environmental Health Priority Workshops Survey Instrument in 2019 2020 [Available from: https://www.enactalabama.org/workshops-fall-2019 .

ENACT. Environmental Health Priority Workshops Survey Instrument in 2018 2020 [Available from: https://www.enactalabama.org/workshops-spring-2018 .

GCR. City of Birmingham Housing and Neighborhood Study. 2014 December 2014.

Posey M. Birmingham mayor orders demolition of nearly 300 abandoned homes in first year www.wbcr.com2018 [Available from: https://www.wbrc.com/2018/11/30/birmingham-mayor-orders-demolition-nearly-abandoned-homes-first-year/ .

EPA. Analyze Trends: Drinking Water Dashboard Enforcement and Compliance History Online at Environmental Protections Agency [Available from: https://echo.epa.gov/trends/comparative-maps-dashboards/drinking-water-dashboard?state=Alabama&view=activity&criteria=basic&yearview=FY .

Byrd TL, VanDerslice J, Peterson SK. Variation in environmental risk perceptions and information sources among three communities in El Paso. Risk. 1997;8:355.

Johnson BB. Risk and culture research: some cautions. J Cross Cult Psychol. 1991;22(1):141–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022191221010 .

Galea S, Tracy M. Participation rates in epidemiologic studies. Ann Epidemiol. 2007;17(9):643–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annepidem.2007.03.013 .

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the funding from a grant from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (R01ES023029). They recognize the crucial role of the Center for the Study of Community Health, supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (cooperative agreement number U48/DP001915). Thanks to focus group and workshop participants and volunteers from community organization partners for their time and efforts.

This work was supported by a grant (R01ES023029) from National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Translational Biology, Medicine, and Health Program, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, Blacksburg, VA, 24061, USA

Department of Population Health Sciences, VA-MD College of Veterinary Medicine, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, 205 Duck Pond Drive, Blacksburg, VA, 24061-0395, USA

Suwei Wang & Julia M. Gohlke

Division of Preventive Medicine, School of Medicine, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL, 35233, USA

Molly B. Richardson

Center for the Study of Community Health, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL, 35233, USA

Mary B. Evans & Katherine L. White

West Central Alabama Community Health Improvement League, Camden, AL, 36726, USA

Ethel Johnson & Sheryl Threadgill-Matthews

Friends of West End, Birmingham, AL, 35228, USA

Sheila Tyson

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

SW analyzed and interpreted data from workshops in 2018 and 2019, contributed to the data acquisition, and was one of the major contributors in writing the manuscript. MR analyzed and interpreted data from focus groups in 2016 and workshops in 2018, contributed to study design and data acquisition, and was one of the major contributors in writing the manuscript. ME, EJ, STM, ST contributed to study design and data acquisition. KW analyzed and interpreted data from focus groups in 2016. JG contributed to the conception, design of work, data acquisition and substantively revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Julia M. Gohlke .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.

This study was approved by Virginia Tech Institutional Review Board (protocol #15–761). All methods were carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from all the participants in the current study.

Consent for publication

Consent for publication from participants had been obtained.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1..

Semi-structured discussion guide for focus groups and activities for workshops.

Additional file 2.

Transcript coding tree to identify persistence reasons, responsible parties, solutions, and source of trusted information.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ . The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver ( http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/ ) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Wang, S., Richardson, M.B., Evans, M.B. et al. A community-engaged approach to understanding environmental health concerns and solutions in urban and rural communities. BMC Public Health 21 , 1738 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11799-1

Download citation

Received : 16 January 2021

Accepted : 08 September 2021

Published : 24 September 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11799-1

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Community-engaged

- Environmental health

- Focus group

- Urban-rural comparison

BMC Public Health

ISSN: 1471-2458

- Submission enquiries: [email protected]

- General enquiries: [email protected]

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

Collection

Human health and the environment

Human health and the environment are inextricably linked at local, national and global scales. Exposure to environmental issues, such as pollution, climate change, extreme heat events and poor water quality, can negatively impact human health and wellbeing. Different populations and groups differ in their vulnerability to environmental degradation, climate change and extreme heat events, often as a result of age demographics and socio-economic inequalities that affect resilience.

In this Collection, we present articles that explore emerging threats to health and wellbeing posed by the environment, health benefits the environment can provide, and policies that can help improve air, water and soil quality, limit pollution and mitigate against extreme events. We welcome submissions of complementary studies and opinion pieces that can help broaden the discussion and further our understanding of the links between human health and the environment.

This Collection supports and amplifies research related to SDG 3 - Good Health and Well-being.

Niheer Dasandi, PhD

University of Birmingham, UK

Kerstin Schepanski, PhD

Freie Universität Berlin, Germany

Fiona Tang, PhD

University of New England, Australia

- Collection content

- Participating journals

- About the Editors

- About this Collection

Reviews & Opinion

Where dirty air is most dangerous

Exposure to poor air quality can damage human health and incur associated costs. The severity of these impacts is not uniform around the globe, but depends on the health and density of the populations.

- Kerstin Schepanski

Climate Change

The diurnal variation of wet bulb temperatures and exceedance of physiological thresholds relevant to human health in South Asia

Human physiological thresholds for uncompensable heat stress were exceeded for more than 300 hours in South Asia between 1995 and 2020, including in the evenings, according to an analysis of the diurnal variability of wet and dry bulb temperatures in station data.

- Jenix Justine

- Joy Merwin Monteiro

Spatio-temporal dynamics of three diseases caused by Aedes -borne arboviruses in Mexico

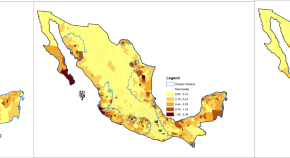

Dong et al. analyse Aedes -borne diseases (ABDs) presence, local climate, and socio-demographic factors of 2,469 municipalities in Mexico, and apply machine learning to predict areas most at risk of ABDs clusters. Dengue was most prevalent, and socio-demographic and climatic factors influenced ABDs occurrence in different regions of Mexico.

- Latifur Khan

- Ubydul Haque

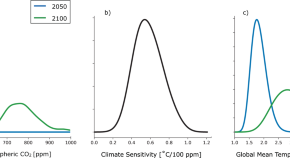

Probabilistic projections of increased heat stress driven by climate change

Exposure to dangerous heat index levels will likely increase by 50-100% in the tropics and by a factor of 3-10 in the mid-latitudes by 2100, even if the Paris Agreement goal of limiting warming to 2°C is met, according to probabilistic projections of global warming.

- Lucas R. Vargas Zeppetello

- Adrian E. Raftery

- David S. Battisti

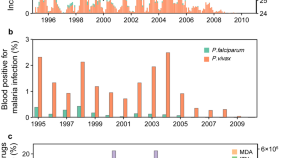

Malaria elimination on Hainan Island despite climate change

Tian et al. use mathematical modelling to estimate the impact of various interventions on malaria incidence on Hainan Island, also taking into account climate change. They find that although malaria transmission has been exacerbated by climate change, insecticide-treated bed nets and other interventions were effective in controlling the disease.

- Huaiyu Tian

- Christopher Dye

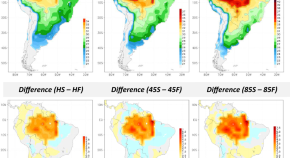

Deforestation and climate change are projected to increase heat stress risk in the Brazilian Amazon

Complete savannization of the Amazon Basin would enhance the effects of climate change on local heat exposure and pose a risk to human health, according to climate model projections.

- Beatriz Fátima Alves de Oliveira

- Marcus J. Bottino

- Carlos A. Nobre

Protecting Brazilian Amazon Indigenous territories reduces atmospheric particulates and avoids associated health impacts and costs

More than 15 million cases of respiratory and cardiovascular infections could be prevented, saving $2 billion USD each year in human health costs by protecting indigenous lands in the Brazilian Amazon, suggest estimates of PM2.5 health impacts between 2010 and 2019.

- Paula R. Prist

- Florencia Sangermano

- Carlos Zambrana-Torrelio

Heavy metal concentrations in rice that meet safety standards can still pose a risk to human health

National safety standard for concentrations of arsenic and cadmium in commercial rice in China are sufficiently high to pose non-negligible health risks especially for chronically exposed children, according to a regionally resolved probability and fuzzy analysis for China.

- Wenfeng Tan

Current wastewater treatment targets are insufficient to protect surface water quality

SDG 6.3 targets to half the proportion of untreated wastewater discharged to the environment by 2030 will substantially improve water quality globally, but a high-resolution surface water quality model suggests key thresholds will still not be met in regions with limited existing wastewater treatment.

- Edward R. Jones

- Marc F. P. Bierkens

- Michelle T. H. van Vliet

Severe atmospheric pollution in the Middle East is attributable to anthropogenic sources

Fine particulate aerosols sampled around the Arabian Peninsula predominantly originate from anthropogenic pollution and constitute one of the leading health risk factors in the region, according to shipborne sampling and numerical atmospheric chemistry modelling.

- Sergey Osipov

- Sourangsu Chowdhury

- Jos Lelieveld

Protecting playgrounds: local-scale reduction of airborne particulate matter concentrations through particulate deposition on roadside ‘tredges’ (green infrastructure)

- Barbara A. Maher

- Tomasz Gonet

- Thomas J. Bannan

Accumulation of trace element content in the lungs of Sao Paulo city residents and its correlation to lifetime exposure to air pollution

- Nathália Villa dos Santos

- Carolina Leticia Zilli Vieira

- Petros Koutrakis

Environmental and health impacts of atmospheric CO 2 removal by enhanced rock weathering depend on nations’ energy mix

Enhanced rock weathering is competitive with other carbon sequestration strategies in terms of land, energy and water use with its overall sustainability dependent on that of the energy system supplying it, according to a process-based life cycle assessment.

- Rafael M. Eufrasio

- Euripides P. Kantzas

- David J. Beerling

Adverse health and environmental outcomes of cycling in heavily polluted urban environments

- Ewa Adamiec

- Elżbieta Jarosz-Krzemińska

- Aleksandra Bilkiewicz-Kubarek

Related reading

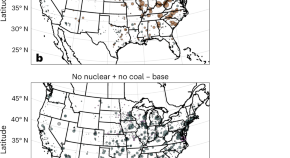

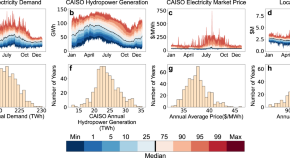

Nuclear power generation phase-outs redistribute US air quality and climate-related mortality risk

How a nuclear power phase-out may affect air pollution, climate and health in the future is up for debate. Here the authors assess impacts of a nuclear phase-out in the United States on ground-level ozone and fine particulate matter (PM 2.5 ).

- Lyssa M. Freese

- Guillaume P. Chossière

- Noelle E. Selin

U.S. West Coast droughts and heat waves exacerbate pollution inequality and can evade emission control policies

Heat waves and droughts increase air pollution from power plants in California, which disproportionately damages counties with a majority of people of color. Droughts cause chronic increases in pollution damages. Heat waves are responsible for the days with the highest damages.

- Amir Zeighami

- Jordan Kern

- August A. Bruno

Effect of air pollution on the human immune system

Inhaled particulates from environmental pollutants accumulate in macrophages in lung-associated lymph nodes over years, compromising immune surveillance via direct effects on immune cell function and lymphoid architecture. These findings reveal the importance of improved air quality to preserve immune health against current and emerging pathogens.

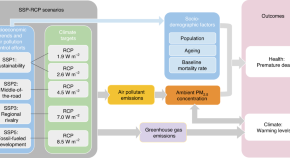

Socio-demographic factors shaping the future global health burden from air pollution

Millions of premature deaths each year can be attributed to ambient particulate air pollution. While exposure to harmful particulates decreases in future scenarios with reduced fossil fuel combustion, across much of the globe, socio-demographic factors dominate health outcomes related to air pollution.

- Xinyuan Huang

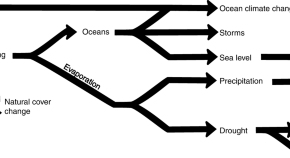

Over half of known human pathogenic diseases can be aggravated by climate change

A systematic review shows that >58% of infectious diseases confronted by humanity, via 1,006 unique pathways, have at some point been affected by climatic hazards sensitive to GHGs. These results highlight the mounting challenge for adaption and the urgent need to reduce GHG emissions.

- Camilo Mora

- Tristan McKenzie

- Erik C. Franklin

Dietary shifts can reduce premature deaths related to particulate matter pollution in China

Population growth and dietary changes affect ammonia emissions from agriculture and the concentration of particulate matter in the atmosphere. This study quantifies the adverse health impacts associated with these processes in China using a mechanistic model of particulate matter formation and transport. It also compares them with direct health impacts of changing diets upon premature death from food-related diseases.

- Xueying Liu

- Amos P. K. Tai

- Hon-Ming Lam

Health co-benefits of climate change mitigation depend on strategic power plant retirements and pollution controls

Climate mitigation policies often provide health co-benefits. Analysis of individual power plants under future climate–energy policy scenarios shows reducing air pollution-related deaths does not automatically align with emission reduction policies and that policy design needs to consider public health.

- Guannan Geng

- Steven J. Davis

The burden of heat-related mortality attributable to recent human-induced climate change

Current and future climate change is expected to impact human health, both indirectly and directly, through increasing temperatures. Climate change has already had an impact and is responsible for 37% of warm-season heat-related deaths between 1991 and 2018, with increases in mortality observed globally.

- A. M. Vicedo-Cabrera

- N. Scovronick

- A. Gasparrini

Anthropogenic emissions and urbanization increase risk of compound hot extremes in cities

Heat extremes threaten the health of urban residents with particularly strong impacts from day–night sustained heat. Observation and simulation data across eastern China show increasing risks of compound events attributed to anthropogenic emissions and urbanization.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Agriculture and the Environment

- Case Studies

- Chemistry and Toxicology

- Environment and Human Health

- Environmental Biology

- Environmental Economics

- Environmental Engineering

- Environmental Ethics and Philosophy

- Environmental History

- Environmental Issues and Problems

- Environmental Processes and Systems

- Environmental Sociology and Psychology

- Environments

- Framing Concepts in Environmental Science

- Management and Planning

- Policy, Governance, and Law

- Quantitative Analysis and Tools

- Sustainability and Solutions

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

The environment in health and well-being.

- George Morris George Morris European Centre for Environment and Human Health, University of Exeter Medical School, Truro, United Kingdom

- and Patrick Saunders Patrick Saunders University of Staffordshire, University of Birmingham, and WHO Collaborating Centre

- https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780199389414.013.101

- Published online: 29 March 2017

Most people today readily accept that their health and disease are products of personal characteristics such as their age, gender, and genetic inheritance; the choices they make; and, of course, a complex array of factors operating at the level of society. Individuals frequently have little or no control over the cultural, economic, and social influences that shape their lives and their health and well-being. The environment that forms the physical context for their lives is one such influence and comprises the places where people live, learn work, play, and socialize, the air they breathe, and the food and water they consume. Interest in the physical environment as a component of human health goes back many thousands of years and when, around two and a half millennia ago, humans started to write down ideas about health, disease, and their determinants, many of these ideas centered on the physical environment.

The modern public health movement came into existence in the 19th century as a response to the dreadful unsanitary conditions endured by the urban poor of the Industrial Revolution. These conditions nurtured disease, dramatically shortening life. Thus, a public health movement that was ultimately to change the health and prosperity of millions of people across the world was launched on an “environmental conceptualization” of health. Yet, although the physical environment, especially in towns and cities, has changed dramatically in the 200 years since the Industrial Revolution, so too has our understanding of the relationship between the environment and human health and the importance we attach to it.

The decades immediately following World War II were distinguished by declining influence for public health as a discipline. Health and disease were increasingly “individualized”—a trend that served to further diminish interest in the environment, which was no longer seen as an important component in the health concerns of the day. Yet, as the 20th century wore on, a range of factors emerged to r-establish a belief in the environment as a key issue in the health of Western society. These included new toxic and infectious threats acting at the population level but also the renaissance of a “socioecological model” of public health that demanded a much richer and often more subtle understanding of how local surroundings might act to both improve and damage human health and well-being.

Yet, just as society has begun to shape a much more sophisticated response to reunite health with place and, with this, shape new policies to address complex contemporary challenges, such as obesity, diminished mental health, and well-being and inequities, a new challenge has emerged. In its simplest terms, human activity now seriously threatens the planetary processes and systems on which humankind depends for health and well-being and, ultimately, survival. Ecological public health—the need to build health and well-being, henceforth on ecological principles—may be seen as the society’s greatest 21st-century imperative. Success will involve nothing less than a fundamental rethink of the interplay between society, the economy, and the environment. Importantly, it will demand an environmental conceptualization of the public health as no less radical than the environmental conceptualization that launched modern public health in the 19th century, only now the challenge presents on a vastly extended temporal and spatial scale.

- environmental and human health

- environment

- environmental epidemiology

- environmental health inequalities

- ecological public health

Introduction

This article traces the development of ideas about the environment in human health and well-being over time. Our primary focus is the period since the early 19th century , sometimes termed the “modern public health era.” This has been not only a time of unprecedented scientific, technological, and societal transition but also a time during which perspectives on the relationship of humans to their environment, and its implications for their health and well-being, have undergone significant change.

Curiosity about the environment as a factor in human health and well-being, and indeed health-motivated interventions to manage the physical context for life, substantially predate the modern public health era. The archaeological record provides evidence of sewer lines, primitive toilets, and water-supply arrangements in settlements in Asia, the Middle East, South America, and Southern Europe, dating back many thousands of years (Rosen, 1993 ). Some religious traditions also imply recognition of the importance of environmental factors in health. For example, restrictions on the consumption of certain foods probably derive from a belief that these foods carried risks to health; a passage in the book of Leviticus conveys the existence of a belief in the relationship between the internal state of a house and the health of its occupants (Leviticus [14:33–45], quoted in Frumkin, 2005 ).

The sixty-two books of the “Hippocratic Corpus” dating from 430–330 bc are the accepted bedrock of Western medicine (Lloyd, 1983 ), not least because they departed from the purely supernatural explanations for health and disease which hitherto held sway. For the first time, ideas about medicine, diseases, and their causes were being written down. Among these were ideas about the environment and its relationship to mental and physical health (Lloyd, 1983 ; Rosen, 1993 ; Kessel, 2006 ). While scarcely a template for how societies would come to think about environment and health in the modern era, one Hippocratic text in particular, On Airs, Waters and Places , introduces several ideas that do retain currency. For example, the simple message that good health is unlikely to be achieved and maintained in poor environmental conditions is enduring. Also, through specific reference to the health relevance of changes in water, soil, vegetation, sunlight, winds, climate, and seasonality, On Airs, Waters and Places conceives an environment made up of distinct compartments and spatial scales from local to global, recognizing that perturbations in these compartments, and on these scales, may result in disease. Such thinking remains conceptually and operationally relevant today. Hazardous agents are still frequently addressed in “environmental compartments” such as water, soil, air, and food or by developing and applying environmental standards for the different categories of place where people work, live, learn, and socialize. In parts, the Hippocratic Corpus also presages the ecological perspectives now coloring 21st-century public health thinking. These include an understanding of the potential for human activity to impact negatively on the natural world and the importance of viewing the body within its environment as a composite whole.

Environment and Health in the Modern Public Health Era

Epidemiology is the basic science of public health and is concerned with the distribution of health and disease in populations across time and spaces, together with the determinants of that distribution. Environmental epidemiology is a subspecialty dealing with the effects of environmental exposures on health and disease, again, in populations. Since the early 19th century , the outputs of epidemiology have been key components of a “mixed economy of evidence” that has shaped and reshaped priorities and informed the decisions society takes to protect and improve population health (Petticrew et al., 2004 ; Baker & Nieuwenhuijsen, 2008 ).