Choose Your Test

Sat / act prep online guides and tips, the 19 steps to becoming a college professor.

Other High School , College Info

Do you love conducting research and engaging with students? Can you envision yourself working in academia? Then you're probably interested in learning how to become a college professor. What are the basic requirements for becoming a college professor? What specific steps should you take in order to become one?

In this guide, we start with an overview of professors, taking a close look at their salary potential and employment growth rate. We then go over the basic college professor requirements before giving you a step-by-step guide on how to become one.

Feature Image: Georgia Southern /Flickr

Becoming a College Professor: Salary and Job Outlook

Before we dive into our discussion of salaries and employment growth rates, it's important to be aware of the incredible challenge of becoming a college professor.

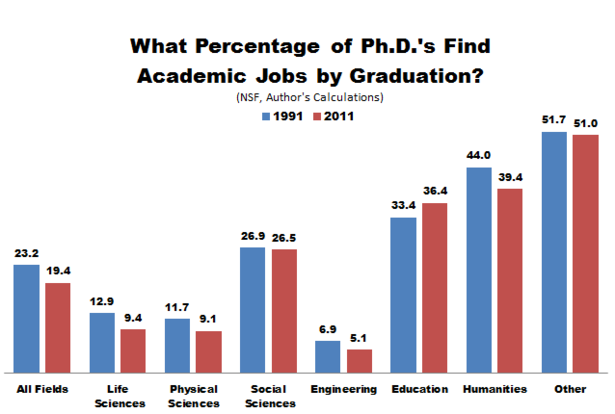

These days, it is unfortunately well known that the number of people qualified to be professors far outnumbers the availability of professor job openings , which means that the job market is extremely competitive. Even if you do all the steps below, the chances of your actually becoming a college professor are slim —regardless of whether you want to teach in the humanities or sciences .

Now that we've gone over the current status of the professor job market, let's take a look at some hard figures for salary and employment growth rate.

Salary Potential for Professors

First, what is the salary potential for college professors? The answer to this question depends a lot on what type of professor you want to be and what school you end up working at .

In general, though, here's what you can expect to make as a professor. According to a recent study conducted by the American Association of University Professors , the average salaries for college professors are as follows :

- Full professors: $140,543

- Associate professors: $95,828

- Assistant professors: $83,362

- Part-time faculty members: $3,556 per standard course section

As you can see, there's a pretty huge range in professors' salaries , with full professors typically making $40,000-$50,000 more per year than what associate and assistant professors make.

For adjunct professors (i.e., part-time teachers), pay is especially dismal . Many adjunct professors have to supplement their incomes with other jobs or even public assistance, such as Medicaid, just to make ends meet.

One study notes that adjuncts make less than minimum wage when taking into account non-classroom work, including holding office hours and grading papers.

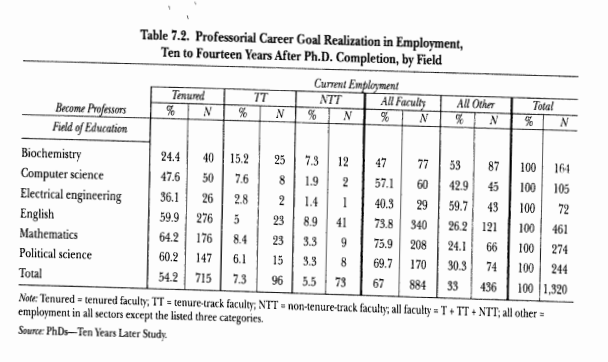

All in all, while it's possible to make a six-figure salary as a college professor, this is rare, especially considering that 73% of college professors are off the tenure track .

Employment Rates for Professors

Now, what about employment rates for professor jobs? According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), the projected growth rate for postsecondary teachers in the years 2020-2030 is 12% —that's 4% higher than the average rate of growth of 8%.

That said, most of this employment growth will be in part-time (adjunct) positions and not full-time ones. This means that most professor job openings will be those with the lowest salaries and lowest job security .

In addition, this job growth will vary a lot by field (i.e., what you teach). The chart below shows the median salaries and projected growth rates for a variety of fields for college professors (arranged alphabetically):

Source: BLS.gov

As this chart indicates, depending on the field you want to teach in, your projected employment growth rate could range from 0% to as high as 21% .

The fastest growing college professor field is health; by contrast, the slowest growing fields are social sciences, mathematical science, atmospheric and earth sciences, computer science, and English language and literature. All of these are growing at a slower-than-average pace (less than 5%).

Law professors have the highest salary , with a median income of $116,430. On the opposite end, the lowest-earning field is criminal justice and law enforcement, whose professors make a median salary of $63,560—that's over $50,000 less than what law professors make.

College Professor Requirements and Basic Qualifications

In order to become a college professor, you'll need to have some basic qualifications. These can vary slightly among schools and fields, but generally you should expect to need the following qualifications before you can become a college professor .

#1: Doctoral Degree in the Field You Want to Teach In

Most teaching positions at four-year colleges and universities require applicants to have a doctoral degree in the field they wish to teach in.

For example, if you're interested in teaching economics, you'd likely need to get a PhD in economics. Or if you're hoping to teach Japanese literature, you'd get a PhD in a relevant field, such as Japanese studies, Japanese literature, or comparative literature.

Doctoral programs usually take five to seven years and require you to have a bachelor's degree and a master's degree. (Note, however, that many doctoral programs do allow you to earn your master's along the way.)

But is it possible to teach college-level classes without a doctoral degree? Yes—but only at certain schools and in certain fields.

As the BLS notes, some community colleges and technical schools allow people with just a master's degree to teach classes ; however, these positions can be quite competitive, so if you've only got a master's degree and are up against applicants with doctorates, you'll likely have a lower chance of standing out and getting that job offer .

In addition, some fields let those with just master's degrees teach classes. For example, for creative writing programs, you'd only need a Master of Fine Arts.

#2: Teaching Experience

Another huge plus for those looking to become professors is teaching experience. This means any experience with leading or instructing classes or students.

Most college professors gain teaching experience as graduate students. In many master's and doctoral programs, students are encouraged (sometimes even required) to either lead or assist with undergraduate classes.

At some colleges, such as the University of Michigan, graduate students can get part-time teaching jobs as Graduate Student Instructors (GSIs) . For this position, you'll usually teach undergraduate classes under the supervision of a full-time faculty member.

Another college-level teaching job is the Teaching Assistant or Teacher's Aide (TA) . TAs assist the main professor (a full-time faculty member) with various tasks, such as grading papers, preparing materials and assignments, and leading smaller discussion-based classes.

#3: Professional Certification (Depending on Field)

Depending on the field you want to teach in, you might have to obtain certification in something in addition to getting a doctoral degree. Here's what the BLS says about this:

"Postsecondary teachers who prepare students for an occupation that requires a license, certification, or registration, may need to have—or they may benefit from having—the same credential. For example, a postsecondary nursing teacher might need a nursing license or a postsecondary education teacher might need a teaching license."

Generally speaking, you'll only need certification or a license of some sort if you're preparing to teach in a technical or vocational field , such as health, education, or accounting.

Moreover, while you don't usually need any teaching certification to be able to teach at the college level, you will need it if you want to teach at the secondary level (i.e., middle school or high school).

#4: Publications and Prominent Academic Presence

A high number of publications is vital to landing a job as a professor. Since full-time college-level teaching jobs are extremely competitive, it's strongly encouraged (read: basically required!) that prospective professors have as many academic publications as possible .

This is particularly important if you're hoping to secure a tenure-track position, which by far offers the best job security for professors. Indeed, the famous saying " publish or perish " clearly applies to both prospective professors and practicing professors.

And it's not simply that you'll need a few scholarly articles under your belt— you'll also need to have big, well-received publications , such as books, if you want to be a competitive candidate for tenure-track teaching positions.

Here's what STEM professor Kirstie Ramsey has to say about the importance of publications and research when applying for tenure-track jobs:

"Many colleges and universities are going through a transition from a time when research was not that important to a time when it is imperative. If you are at one of these institutions and you were under the impression that a certain amount of research would get you tenure, you should not be surprised if the amount of research you will need increases dramatically before you actually go up for tenure. At first I thought that a couple of peer-reviewed articles would be enough for tenure, especially since I do not teach at a research university and I am in a discipline where many people do not go into academe. However, during my first year on the tenure track at my current institution, I realized that only two articles would not allow me to jump through the tenure hoop."

To sum up, it's not just a doctorate and teaching experience that make a professor, but also lots and lots of high-quality, groundbreaking research .

How to Become a Professor: 19-Step Guide

Now that we've gone over the basic college professor requirements, what specific steps should you take to become one? What do you need to do in high school? In college? In graduate school?

Here, we introduce to you our step-by-step guide on how to become a college professor . We've divided the 19 steps into four parts:

- High School

- Graduate School (Master's Degree)

- Graduate School (Doctorate)

Part 1: High School

It might sound strange to start your path to becoming a professor in high school, but doing so will make the entire process go a lot more smoothly for you. Here are the most important preliminary steps you can take while still in high school.

- Step 1: Keep Up Your Grades

Although all high school students should aim for strong GPAs , because you're specifically going into the field of education, you'll need to make sure you're giving a little extra attention to your grades . Doing this proves that you're serious about not only your future but also education as a whole—the very field you'll be entering!

Furthermore, maintaining good grades is important for getting into a good college . Attending a good college could, in turn, help you get into a more prestigious graduate school and obtain a higher-paying teaching job .

If you already have an idea of what subject you'd like to teach, try to take as many classes in your field as possible . For example, if you're a lover of English, you might want to take a few electives in subjects such as journalism or creative writing. Or if you're a science whiz, see whether you can take extra science classes (beyond the required ones) in topics such as marine science, astronomy, or geology.

Again, be sure that you're getting high marks in your classes , particularly in the ones that are most relevant to the field you want to teach in.

- Step 2: Tutor in Your Spare Time

One easy way of gaining teaching experience as a high school student is to become a tutor. Pick a subject you're strong at—ideally, one you might want to eventually teach—and consider offering after-school or weekend tutoring services to your peers or other students in lower grades.

Tutoring will not only help you decide whether teaching is a viable career path for you, but it'll also look great on your college applications as an extracurricular activity .

- Step 3: Get a High SAT/ACT Score

Since you'll need to go to graduate school to become a professor, it'll be helpful if you can get into a great college. To do this, you'll need to have an impressive SAT/ACT score .

Ideally, you'll take your first SAT or ACT around the beginning of your junior year. This should give you enough time to take the test again in the spring, and possibly a third time during the summer before or the autumn of your senior year.

The SAT/ACT score you'll want to aim for depends heavily on which colleges you apply to.

For more tips on how to set a goal score, check out our guides to what a great SAT / ACT score is .

- Step 4: Submit Impressive College Applications

Though it's great to attend a good college, where you go doesn't actually matter too much—just as long as it offers an academic program in the (broad) field or topic you're thinking of teaching in.

To get into the college of your choice, however, you'll still want to focus on putting together a great application , which will generally include the following:

- A high GPA and evidence of rigorous coursework

- Impressive SAT/ACT scores

- An effective personal statement/essay

- Strong letters of recommendation (if required)

Be sure to give yourself plenty of time to work on your applications so you can submit the best possible versions of them before your schools' deadlines .

If you're aiming for the Ivy League or other similarly selective institutions, check out our expert guide on how to get into Harvard , written by a real Harvard alum.

Part 2: College

Once you get into college, what can you do to help your chances of getting into a good grad school and becoming a college professor? Here are the next steps to take.

- Step 5: Declare a Major in the Field You Want to Teach

Perhaps the most critical step is to determine what exactly you want to teach in the future—and then major in it (or a related field) . For instance, if after taking some classes in computer science you decide that you really want to teach this subject, then go ahead and declare it as your major.

If you're still not sure what field you'll want to teach in, you can always change your major later on or first declare your field of interest as a minor (and then change it to a major if you wish). If the field you want to teach is not offered as a major or minor at your college, try to take as many relevant classes as possible.

Although it's not always required for graduate school applicants to have majored in the field they wish to study at the master's or doctoral level, it's a strong plus in that it shows you've had ample experience with the subject and will be able to perform at a high level right off the bat.

- Step 6: Observe Your Professors in Action

Since you're thinking of becoming a college professor, this is a great time to sit down and observe your professors to help you determine whether teaching at the postsecondary level is something you're truly interested in pursuing.

In your classes, evaluate how your professors lecture and interact with students . What kinds of tools, worksheets, books, and/or technology do they use to effectively engage students? What sort of atmosphere do they create for the class?

It's also a good idea to look up your professors' experiences and backgrounds in their fields . What kinds of publications do they have to their name? Where did they get their master's and doctoral degrees? Are they tenured or not? How long have they been teaching?

If possible, I recommend meeting with a professor directly (ideally, one who's in the same field you want to teach in) to discuss a career in academia. Most professors will be happy to meet with you during their office hours to talk about your career interests and offer advice.

Doing all of this will give you an inside look at what the job of professor actually entails and help you decide whether it's something you're passionate about.

- Step 7: Maintain Good Grades

Because you'll need to attend graduate school after college, it's important to maintain good grades as an undergraduate, especially in the field you wish to teach. This is necessary because most graduate programs require a minimum 3.0 undergraduate GPA for admission .

Getting good grades also ensures that you'll have a more competitive application for grad school, and indicates that you take your education seriously and are passionate about learning.

- Step 8: Get to Know Your Professors

Aside from watching how your professors teach, it's imperative to form strong relationships with them outside of class , particularly with those who teach in the field you want to teach as well.

Meet with professors during their office hours often. Consult them whenever you have questions about assignments, papers, projects, or your overall progress. Most importantly, don't be afraid to talk to them about your future goals!

You want to build a strong rapport with your professors, which is basically the same thing as networking. This way, you'll not only get a clearer idea of what a professor does, but you'll also guarantee yourself stronger, more cogent letters of recommendation for graduate school .

- Step 9: Gain Research and/or Publication Experience

This isn't an absolute necessity for undergraduates, but it can certainly be helpful for your future.

If possible, try to gain research experience through your classes or extracurricular projects . For instance, you could volunteer to assist a professor with research after class or get a part-time job or internship as a research assistant.

If neither option works, consider submitting a senior thesis that involves a heavy amount of research . Best case scenario, all of your research will amount to a publication (or two!) with your name on it.

That being said, don't fret too much about getting something published as an undergraduate . Most students don't publish anything in college yet many go on to graduate school, some of whom become college professors. Rather, just look at this as a time to get used to the idea of researching and writing about the results of your research.

- Step 10: Take the GRE and Apply to Grad School

If you're hoping to attend graduate school immediately after college, you'll need to start working on your application by the fall of your senior year .

One big part of your graduate school application will be GRE scores , which are required for many graduate programs. The GRE is an expensive test , so it's best if you can get away with taking it just once (though there's no harm in taking it twice).

Although the GRE isn't necessarily the most important feature of your grad school application , you want to make sure you're dedicating enough time to it so that it's clear you're really ready for grad school.

Other parts of your grad school application will likely include the following:

- Undergraduate transcripts

- Personal statement / statement of purpose

- Curriculum vitae (CV) / resume

- Letters of recommendation

For more tips on the GRE and applying to grad school, check out our GRE blog .

Part 3: Graduate School (Master's Degree)

Once you've finished college, it's time to start thinking about graduate school. I'm breaking this part into two sections: master's degree and doctorate .

Note that although some doctoral programs offer a master's degree along the way, others don't or prefer applicants who already have a master's degree in the field.

- Step 11: Continue to Keep Up Your Grades

Again, one of your highest priorities should be to keep up your grades so you can get into a great doctoral program once you finish your master's program. Even more important, many graduate programs require students to get at least Bs in all their classes , or else they might get kicked out of the program! So definitely focus on your grades.

- Step 12: Become a TA

One great way to utilize your graduate program (besides taking classes!) is to become a Teaching Assistant, or TA, for an undergraduate class. As a TA, you will not only receive a wage but will also gain lots of firsthand experience as a teacher at the postsecondary level .

Many TAs lead small discussion sections or labs entirely on their own, offering a convenient way to ease into college-level teaching.

TAs' duties typically involve some or all of the following:

- Grading papers and assignments

- Leading small discussion or lab sections of a class (instead of its large lecture section)

- Performing administrative tasks for the professor

- Holding office hours for students

The only big negative with being a TA is the time commitment ; therefore, be sure you're ready and willing to dedicate yourself to this job without sacrificing your grades and academic pursuits.

- Step 13: Research Over the Summer

Master's programs in the US typically last around two years, giving you at least one summer during your program. As a result, I strongly recommend using this summer to conduct some research for your master's thesis . This way you can get a head start on your thesis and won't have to cram in all your research while also taking classes.

What's more, using this time to research will give you a brief taste of what your summers might look like as a professor , as college professors are often expected to perform research over their summer breaks .

Many graduate programs offer summer fellowships to graduate students who are hoping to study or conduct research (in or outside the US). My advice? Apply for as many fellowships as possible so you can give yourself the best chance of getting enough money to support your academic plans.

- Step 14: Write a Master's Thesis

Even if your program doesn't require a thesis, you'll definitely want to write one so you can have proof that you're experienced with high-level research . This type of research could help your chances of getting into a doctoral program by emphasizing your commitment to the field you're studying. It will also provide you with tools and experiences that are necessary for doing well in a doctoral program and eventually writing a dissertation.

Step 15: Apply to Doctoral Programs OR Apply for Teaching Jobs

This step has two options depending on which path you'd rather take.

If you really want to teach at a four-year college or university, then you must continue on toward a doctorate . The application requirements for doctoral programs are similar to those for master's programs . Read our guide for more information about grad school application requirements .

On the other hand, if you've decided that you don't want to get a doctorate and would be happy to teach classes at a community college or technical school, it's time to apply for teaching jobs .

To start your job hunt, meet with some of your current or past professors who teach in the field in which you'll also be teaching and see whether they know of any job openings at nearby community colleges or technical schools. You might also be able to use some professors as references for your job applications (just be sure to ask them before you write down their names!).

If you can't meet with your professors or would rather look for jobs on your own, try browsing the career pages on college websites or looking up teaching jobs on the search engine HigherEdJobs .

Part 4: Graduate School (Doctorate)

The final part of the process (for becoming a college professor at a four-year institution) is to get your doctoral degree in the field you wish to teach . Here's what you'll need to do during your doctoral program to ensure you have the best chance of becoming a college professor once you graduate.

- Step 16: Build Strong Relationships With Professors

This is the time to really focus on building strong relationships with professors—not just with those whose classes you've taken but also with those who visit the campus to give talks, hold seminars, attend conferences, etc. This will give you a wider network of people you know who work in academia, which will (hopefully) make it a little easier for you to later land a job as a professor.

Make sure to maintain a particularly strong relationship with your doctoral advisor . After all, this is the professor with whom you'll work the most closely during your time as a doctoral student and candidate. Be open with your advisor : ask her for advice, meet with her often, and check that you're making satisfactory progress toward both your doctorate and your career goals.

- Step 17: Work On Getting Your Research Published

This is also the time to start getting serious about publishing your research.

Remember, it's a huge challenge to find a job as a full-time professor , especially if all you have is a PhD but no major publications. So be sure to focus on not only producing a great dissertation but also contributing to essays and other research projects .

As an article in The Conversation notes,

"By far the best predictor of long-term publication success is your early publication record—in other words, the number of papers you've published by the time you receive your PhD. It really is first in, best dressed: those students who start publishing sooner usually have more papers by the time they finish their PhD than do those who start publishing later."

I suggest asking your advisor for advice on how to work on getting some of your research published if you're not sure where to start.

- Step 18: Write a Groundbreaking Dissertation

You'll spend most of your doctoral program working on your dissertation—the culmination of your research. In order to eventually stand out from other job applicants, it's critical to come up with a highly unique dissertation . Doing this indicates that you're driven to conduct innovative research and make new discoveries in your field of focus.

You might also consider eventually expanding your dissertation into a full-length book .

- Step 19: Apply for Postdoc/Teaching Positions

Once you've obtained your doctorate, it's time to start applying for college-level teaching jobs!

One option you have is to apply for postdoctoral (postdoc) positions . A postdoc is someone who has a doctorate and who temporarily engages in "mentored scholarship and/or scholarly training." Postdocs are employed on a short-term basis at a college or university to help them gain further research and teaching experience.

While you can theoretically skip the postdoc position and dive straight into applying for long-term teaching jobs, many professors have found that their postdoc work helped them build up their resumes/CVs before they went on to apply for full teaching positions at colleges .

In an article for The Muse , Assistant Professor Johanna Greeson at Penn writes the following about her postdoc experience:

"Although I didn't want to do a post-doc, it bought me some time and allowed me to further build my CV and professional identity. I went on the market a second time following the first year of my two-year post-doc and was then in an even stronger position than the first time."

Once you've completed your postdoc position, you can start applying for full-time faculty jobs at colleges and universities. And what's great is that you'll likely have a far stronger CV/resume than you had right out of your doctoral program .

Conclusion: How to Become a College Professor

Becoming a college professor takes years of hard work, but it's certainly doable as long as you know what you'll need to do in order to prepare for the position and increase your chances of securing a job as a professor.

Overall, it's extremely difficult to become a professor. Nowadays, there are many more qualified applicants than there are full-time, college-level teaching positions , making tenure-track jobs in particular highly competitive.

Although the employment growth rate for professors is a high 11%, this doesn't mean that it'll be easy to land a job as a professor . Additionally, salaries for professors can vary a lot depending on the field you teach in and the institution you work at; you could make as little as minimum wage (as an adjunct/part-time professor) or as much as $100,000 or higher (as a full professor).

For those interested in becoming a professor, the basic college professor requirements are as follows :

- A doctoral degree in the field you want to teach in

- Teaching experience

- Professional certification (depending on your field)

- Publications and prominent academic presence

In terms of the steps needed for becoming a college professor, I will list those again briefly here. Feel free to click on any steps you'd like to reread!

- Step 15: Apply to Doctoral Programs or Apply for Teaching Jobs

Good luck with your future teaching career!

What's Next?

Considering other career paths besides teaching? Then check out our in-depth guides to how to become a doctor and how to become a lawyer .

No matter what job (or jobs!) you end up choosing, you'll likely need a bachelor's degree—ideally, one from a great school. Get tips on how to submit a memorable college application , and learn how to get into Harvard and other Ivy League schools with our expert guide.

Need help finding jobs? Take a look at our picks for the best job search websites to get started.

Hannah received her MA in Japanese Studies from the University of Michigan and holds a bachelor's degree from the University of Southern California. From 2013 to 2015, she taught English in Japan via the JET Program. She is passionate about education, writing, and travel.

Ask a Question Below

Have any questions about this article or other topics? Ask below and we'll reply!

Improve With Our Famous Guides

- For All Students

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 160+ SAT Points

How to Get a Perfect 1600, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 800 on Each SAT Section:

Score 800 on SAT Math

Score 800 on SAT Reading

Score 800 on SAT Writing

Series: How to Get to 600 on Each SAT Section:

Score 600 on SAT Math

Score 600 on SAT Reading

Score 600 on SAT Writing

Free Complete Official SAT Practice Tests

What SAT Target Score Should You Be Aiming For?

15 Strategies to Improve Your SAT Essay

The 5 Strategies You Must Be Using to Improve 4+ ACT Points

How to Get a Perfect 36 ACT, by a Perfect Scorer

Series: How to Get 36 on Each ACT Section:

36 on ACT English

36 on ACT Math

36 on ACT Reading

36 on ACT Science

Series: How to Get to 24 on Each ACT Section:

24 on ACT English

24 on ACT Math

24 on ACT Reading

24 on ACT Science

What ACT target score should you be aiming for?

ACT Vocabulary You Must Know

ACT Writing: 15 Tips to Raise Your Essay Score

How to Get Into Harvard and the Ivy League

How to Get a Perfect 4.0 GPA

How to Write an Amazing College Essay

What Exactly Are Colleges Looking For?

Is the ACT easier than the SAT? A Comprehensive Guide

Should you retake your SAT or ACT?

When should you take the SAT or ACT?

Stay Informed

Get the latest articles and test prep tips!

Looking for Graduate School Test Prep?

Check out our top-rated graduate blogs here:

GRE Online Prep Blog

GMAT Online Prep Blog

TOEFL Online Prep Blog

Holly R. "I am absolutely overjoyed and cannot thank you enough for helping me!”

- Self & Career Exploration

- Blue Chip Leadership Experience

- Experiential Learning

- Research Experiences

- Transferable Skills

- Functional Skills

- Resume, CV & Cover Letter

- Online Profiles

- Networking & Relationship Building

- Internships

- Interviewing

- Offer Evaluation & Negotiation

- Career Core by Kaplan

- Arts & Media

- Commerce & Management

- Data & Technology

- Education & Social Services

- Engineering & Infrastructure

- Environment & Resources

- Global Impact & Public Service

- Health & Biosciences

- Law & Justice

- Research & Academia

- Recent Alumni

- Other Alumni Interest Areas

- People of Color

- First Generation

- International

- Faculty & Staff

- Parents & Families

From PhD to Professor: Advice for Landing Your First Academic Position

- Share This: Share From PhD to Professor: Advice for Landing Your First Academic Position on Facebook Share From PhD to Professor: Advice for Landing Your First Academic Position on LinkedIn Share From PhD to Professor: Advice for Landing Your First Academic Position on X

I am living the dream.

At least, my professional dream, that is. I have the perfect job for me. And I’m going to share with you how I got it.

First, a little about me. This August, I started my second year of being a tenure-track assistant professor at the University of Pennsylvania in the School of Social Policy & Practice, a program that is consistently ranked in the Top 15 in the country by U.S. News & World Report and one of only two Ivy League social work programs.

As new junior faculty member, I only teach one course each semester so that I have the time to launch my independent program of research. No dumping major course loads on the new assistant professors here! And as with all faculty at my school, I will only ever be required to teach two courses per semester at most, with the option of “buying out” of teaching when I have grant funding.

Additionally, as a new assistant professor, I am given priority selection for the courses I teach, having the school try its best to accommodate my expertise and interest. As soon as I started last year, my dean set up “meet and greets” with key players in my research area in Philadelphia and supported the development and submission of my application for a small, internal grant from the Provost’s Office for the first study in my research portfolio.

I could actually keeping going with why my job is so awesome, but that’s not the point of this article! Instead, I’m going to share what I learned getting to this point—my advice for other PhDs and aspiring professors out there on how to play the academic job search game and win big. Here are five strategies that really boosted my application and helped me land my dream position.

Related: Go to Grad School Guide: PhD Programs

1. Prioritize Publishing

The same publishing rule that echoes through the halls of academia for professors holds true for emerging scholars and newly minted PhDs: “Publish or perish.” A recent article published in The Conversation confirms what I found as true with my own experience: The best predictor of long-term publication success is your early publication record, or the number of papers you’ve published by the time you receive your PhD. And long-term publication success is at the top of the list for what chairs and deans hope their new assistant professors achieve, as this is what ultimately leads to tenure at places like Penn.

In other words, it’s crucial to prioritize publishing now, long before you graduate. I entered my PhD program in 2005, my first two papers came out in 2007, and I published at least two papers per year through my graduation in 2009. When I visited Penn to interview, I had another four papers on my CV , and I know that this early publication success was critical throughout the steps of my candidacy, from the invitation for the conference interview to the campus interview to the job offer.

Of course, a lot of your early publishing success as a PhD student will depend on your research advisor and mentor. I was very fortunate to have a mentor who took great joy in mentoring doctoral students and prioritized getting them involved in paper-writing early on. If you find yourself with someone who is not prioritizing your publication record, however, I recommend having a serious conversation with him or her about your needs and the importance of publishing early—or finding a new mentor. As you probably already know, you have limited time to publish while pursuing your PhD, and the publication process is notorious for taking a very long time to unfold. Prioritize it now.

2. Have a Mission Statement—and Show it Off

My professional mission is to improve the lives for youth who age out of foster care, and I intend to achieve this mission by working to reform the child welfare system so that no youth leaves foster care without a lifetime connection to a caring adult.

Having this mission—and having it spelled out—is what I believe sold my dean during my conference interview. In fact, I provided him and the other two faculty interviewers with a handout of the image below, a visual depiction of the principles and values that guide my mission and a plan for how I intend to achieve it. I think my colleagues were impressed by the fact that I had a visual plan that I could easily explain for how I imagined achieving my professional mission, and also by my creativity. Although a bulleted list could have accomplished the same thing, I believe the packaging made a difference.

Think about how you can explain your own vision and your tactical goals in a compelling way, and be specific about how you’ll make a difference as an assistant professor. For those of us at research-intensive institutions, this will generally take the form of ideas about how you will fund your research mission with grants. If you’re pursuing teaching-oriented places, you can develop a similar vision and mission statement, but make it oriented toward educating, mentoring, and inspiring students.

3. Know the Game

And a game it is. Up until this moment, my experience, probably like many of you, had been that if you work hard, do the right things, and make good choices, you are rewarded—a meritocracy. However, that’s not how the faculty game works (and no one really tells you this)!

Rather, academic hiring decisions are based on “fit,” and if you’re not the right fit, for whatever reason, you won’t receive the offer no matter how impressive your CV is. “Fit” can mean everything from your area of research to what you teach to what a given school may need with respect to faculty demographics and diversity to such mercurial things as faculty personality. Although job postings do tend to detail the research or teaching areas a given school may be looking for, these are often broad, and there can be more than one in a given announcement.

You might think the answer here is to try to be what any particular program wants you to be in order to “fit” in, but I think the real lesson is to take the game for what it is: It’s about them—not about you. Although demonstrating how you see yourself fitting in to a particular program—for example, by showing how your research would complement or add value to a department—is very important to do, in the end, you can’t make a square peg fit a round hole. All you can do is to apply, give it your best shot, and realize that in the end, it’s about them.

4. Have a Plan B

The first time I went on the job market, despite several conference interviews with an array of schools and a successful campus visit and job talk at Michigan, I received no offers. My colleague and fellow new assistant professor Antonio Garcia identified with my experience: “I, too, completed several successful interviews, but to no avail. I did not receive any offers for a tenure track position during my last year of dissertation work.”

So what happened? We both fell back on Plan B: post-doc positions. Although I didn’t want to do a post-doc, it bought me some time and allowed me to further build my CV and professional identity. I went on the market a second time following the first year of my two-year post-doc and was then in an even stronger position than the first time. Professor Garcia also landed his tenure track position following the first year of his post-doc. “Although my first choice was not to delay the tenure clock, it has since worked to my advantage,” he explains. “I benefitted from having time to a meticulously develop my research agenda, publish manuscripts, and develop and maintain long-lasting inter-disciplinary relationships. I strongly believe the two-year post-doc will ultimately provide me with better odds of receiving tenure.”

Fact is, you may not land the assistant professor job of your dreams—or even an assistant professor job—the first time you try. So, it’s incredibly important to have a Plan B, whether that’s a post-doc or a job with a private research firm that still allows you to build your publication record and gain other worthwhile experience that can translate to academia, like presenting your work at professional conferences.

Related: 3 Steps to Turn Any Setback Into a Success

5. Swallow Your Pride

I actually applied to Penn twice—the first time I went on the market I was unsuccessful, but after the first year of my post-doc, I saw another job posting and as best I could tell, I was a good “fit.” I had a bit of a pride issue about knocking on Penn’s door again, but I also realized that if I didn’t, only one thing was certain: I would never work there. So I swallowed my pride, I knocked again, and I landed the job of my dreams. In fact, as I was leaving the hotel suite where I had my conference interview, one of the faculty interviewers said, “I’m so glad you decided to apply again.”

Finding your first professorship isn’t an easy road, but it’s important to persevere and to stay focused on your long-term goals. Penn psychology professor and recently named MacArthur “genius” Fellow Angela Duckworth defines this philosophy as “grit.”

I liken it to surfing. In fact, during my job talk at Penn, while sharing my vision with the hiring committee, I also shared this: “When considering a research-oriented career, a particular quote comes to mind, ‘You can’t stop the waves, but you can learn to surf.’ If we think of a research career as the surface of a lake or ocean, there are always waves, sometimes big, sometimes small. Nothing we do can stop the waves, but we can learn to surf.”

There are no guarantees that, even if you do all these things, you will land your dream faculty job. But I hope these tips will help you feel perhaps a little more in control while the waves splash over. Try to have fun with this process, at least as much as you can, and may you, too, soon find yourself living the dream.

Link to original article: https://www.themuse.com/advice/from-phd-to-professor-advice-for-landing-your-first-academic-position

About the Author:

Johanna Greeson of The University of Pennsylvania School of Social Policy & Practice

Johanna K.P. Greeson, PhD, MSS, MLSP, is an Assistant Professor at Penn. She is passionate about reforming the child welfare system, using research to build better futures for youth who age out of foster care, and realizing the power of connections to caring adults for all vulnerable youth. Her research agenda is resiliency-focused and based in the strengths and virtues that enable foster youth to not only survive, but thrive.

We respectfully acknowledge the University of Arizona is on the land and territories of Indigenous peoples. Today, Arizona is home to 22 federally recognized tribes, with Tucson being home to the O'odham and the Yaqui. Committed to diversity and inclusion, the University strives to build sustainable relationships with sovereign Native Nations and Indigenous communities through education offerings, partnerships, and community service.

Calculate for all schools

Your chance of acceptance, your chancing factors, extracurriculars, becoming a professor: what does it take.

I'm genuinely curious about what it takes to become a professor. I'm still in high school, so I have a long way to go, but any advice on the path to follow, potential specializations, and overall challenges would be appreciated.

Becoming a professor requires dedication, commitment, and several years of higher education, but it can be a rewarding career path for those passionate about their field and interested in research and teaching. Here's a general outline of the steps and considerations to keep in mind:

1. Pursue a bachelor's degree: First, you'll need to earn a bachelor's degree in your chosen field. Many future professors choose a major related to their intended area of specialization, but this isn't always a requirement. Keep your grades up, as a competitive GPA can help you get into graduate programs and secure funding opportunities.

2. Gain research and teaching experience: While pursuing your undergraduate degree, look for opportunities to get involved in research projects and gain teaching experience. These could include working as a teaching assistant or tutoring your peers. These experiences can help build your skills and make you a more competitive candidate for graduate programs.

3. Pursue a master's degree (optional): Depending on your area of study and career goals, you may want to pursue a master's degree. Some universities and disciplines require a master's degree before entering a PhD program, while others may admit students with a bachelor's degree directly into their PhD programs.

4. Earn a PhD: A doctorate is typically required to become a professor. PhD programs involve significant coursework, research, and usually teaching or assisting with courses. Your PhD research will culminate in a dissertation, which you'll defend in front of a committee of experts in your field.

5. Seek postdoctoral experience: Many aspiring professors look for postdoctoral positions after completing their PhD. These are temporary research positions aimed at helping you gain more experience and build your publication record. They can be crucial in securing a tenure-track faculty position.

6. Apply for tenure-track positions: Tenure-track positions are the traditional path to becoming a professor. These positions involve balancing research, teaching, and service. You'll need to demonstrate strong progress in each area to eventually achieve tenure. Networking and presenting your research at conferences can help broaden your prospects.

7. Achieve tenure: After several years in a tenure-track position, you'll go through a review process to determine whether you'll be granted tenure. Tenure provides job security and is a significant milestone in an academic career. Achieving tenure may involve demonstrating a strong research record, effective teaching, and service to your institution.

Keep in mind that becoming a professor is highly competitive, and finding a tenure-track position can be challenging. However, if you're passionate about your field, committed to research and teaching, and flexible in your career plans, it can be a rewarding path. To give yourself the best chance of success, make the most of networking opportunities, stay productive in your research, and continually hone your teaching skills. Good luck!

About CollegeVine’s Expert FAQ

CollegeVine’s Q&A seeks to offer informed perspectives on commonly asked admissions questions. Every answer is refined and validated by our team of admissions experts to ensure it resonates with trusted knowledge in the field.

How to Become a College Professor: Degrees & Requirements

By Jon Konen, District Superintendent

The truth is, most of that is probably in your head.

The goal of your professors is not to judge you, but to help you learn and expand your potential. It’s a job that comes with a lot of control and freedom, but also involves a real commitment.

Professors are dedicated to knowledge and education. They thrive on teaching and intellectual reasoning and discovery.

Becoming a professor is a dream job if you thrive in the world of theory and knowledge. If your dream is to expand the bounds of human knowledge, to share what you have learned, and to change lives, then a professorship is right up your alley.

Many college professors don’t set out to join that profession. It’s a job that sneaks up on some people. After years studying or working in a field, suddenly the option to teach in that field becomes a viable option. It offers up new opportunities to explore and innovate. Maybe just as important, it’s an opportunity to pass along what you have learned to the next generation of professionals. You can shape your industry, and the world.

Although college professors are definitely educators, that doesn’t mean they need a degree in education. In fact, they flip the script for teaching on its head. They are expected first and foremost to be experts in their own field, and learn pedagogical techniques and principles later on.

This means that becoming a professor doesn’t always follow a straight path, but in a basic sense the process will almost always include these five steps.

How to Become a College Professor in 5 Steps

One unique thing about getting started down the path to learning how to become a college professor is that you don’t really need to take the prescribed steps in order.

Sure, some of them have to come before others—you need an undergraduate degree before anyone will admit you to a PhD program, for example—but otherwise it’s a list of requirements you can check off at almost any stage of your career.

There is enormous competition for these jobs, though. The further you go along to path, the harder each step will become. You’ll need brains, dedication, and a lot of luck to make it all the way to becoming a college professor.

How long does it take to become a college professor?

For the typical pathway to professorship, you can expect a minimum of 8 to 11 years from high school graduation to the front of the lecture hall. But this depends a great deal on your field of study.

Fields that require real-world work experience can add another five years to a decade to your journey. And most professors find their calling along the way, not necessarily pursuing a straight path to the job. Those years of gaining experience and sharpening your skills can add decades to the process.

1. Get a Four-Year Bachelor’s Degree

If you want to teach college, you had better be a college graduate. In every case, that starts with earning a four-year bachelor’s degree.

Because becoming a professor is a long process, with a lot of different paths that can lead to it, your bachelor’s doesn’t necessarily have to be in the field you want to teach in. Many people shift interests through the course of their academic career.

It is important to lay the groundwork for developing your knowledge through education over the long-term. As you’ll see, becoming a professor requires a lot of advanced research and study. Your undergraduate program should equip you with the kind of skills you need to branch out into further learning and research.

Just about any bachelor’s major relevant to your general area of interest can lay the foundation for more advanced study if becoming a professor is your long-term goal.

Want to become a professor of education? Then it’s going to take a degree in education to get you started down the right path. Ready to take the next step? Find teaching degree programs near you!

2. Earn an Advanced Degree in Your Area of Expertise

To teach any material at the college level, you need a deep understanding of the theory and concepts behind it. That’s always going to mean earning an advanced degree in the subject.

Research can be an important part of professorial work, and master’s and doctoral level programs are exactly where you learn how to do that work.

The research required as part of your studies, and eventually your thesis and dissertation projects, are also a primary way for you to develop an advanced understanding of your field.

This is also an important time to cultivate mentors and relationships in your field. When you get to the point where you are applying for positions, you’ll find that the academic field is a pretty small community, so who you know matters.

Your professors in grad school will know people on the hiring committees at the colleges and universities where you will be interviewing later on. If you impressed them, you can expect a good word in the right ears.

What degree do you need to be a college professor? … Does a college professor need a PhD?

The PhD, or Doctor of Philosophy, has long been the standard degree requirement for college professors. Many community colleges and other two-year schools may require only a master’s degree, however. There are also certain areas of study where a PhD is not considered necessary, such as acting and music. Almost all traditional academic departments at four-year universities definitely prefer to higher doctoral graduates as professors, however.

For example, you’ll want to earn a doctorate in education if you plan to become a professor of education.

Can you be a professor with a master’s degree?

It’s most common to find professors teaching with only a master’s degree at the community college level, or working as adjunct faculty at four-year colleges. Adjuncts are the academic version of temps, but they make up the majority of faculty in American universities. According to NCES, in 2018, 54 percent of instructors at degree-granting post-secondary institutions were adjunct faculty.

In many fields, however, there is a surplus of PhD graduates, which makes competition stiff even for adjunct positions. In these fields, a master’s-level professor position is rare.

3. Build Real-world Experience in Your Field

But if you’re aiming to be a professor in journalism, medicine, engineering, or just about any other field with practical applications, most colleges want to see that you have what it takes to do what you will teach . That means holding down a job and racking up some accomplishments to build up that CV you’ll be submitting to the hiring committee.

Colleges and universities actively seek out professors who have expertise in cutting-edge subjects in their field. You’ll want to look for jobs that will give you experience in the kinds of topics that will be most important to the future of your field. That’s exactly what students are going to come to school to learn.

How To Be a College Professor Without a PhD

The drive to be the school with the most cutting-edge curriculum in a given field is one that can push hiring committees away from that PhD standard. If you can develop the right expertise, and a reputation to match, then it’s possible you can meet the college professor requirements without having a doctorate.

If there is big demand for professors in a particular field, you can sometimes find temporary work with only a master’s degree. If you earn a master’s degree in education , for example, you might be able to get a job instructing teachers as an adjunct professor.

It’s also much easier to become a professor without a PhD if you want to teach in a field where PhDs aren’t the standard mark of expertise. Arts programs, for example, generally show preference to instructors with experience and expertise over those with impressive academic credentials who may not have a lot of experience because the paths to those industries often don’t run through college.

4. Get Hired as a College Professor

Once you have the experience and the education to become qualified, you can start hunting for jobs teaching in college classrooms.

At first, you’ll almost certainly start as an adjunct, teaching part-time or in a visiting position at community colleges or small universities. Since there are no real professional pedagogical standards in college instruction, this serves as a sort of apprenticeship where you cut your teeth learning how to actually transfer your knowledge to students.

At the entry level, college professors don’t have a lot of options in the job market. You will very likely have to relocate to an area with a school willing to hire you. You’ll go through a lot of interviews and apply to a lot of positions to get your foot in the door.

The process and timing will vary from field to field. Many have specialized publications, like PhilJobs.org for philosophy positions, where openings are posted.

Your qualifications and specialties are very important. Schools are often looking for very specific areas of expertise to shore up their existing faculty range. Frequently, the pedigree of your education will matter. A degree from a big-name school gets you further than a small state college no one has ever heard of.

Different colleges and different departments within those colleges have different priorities when it comes to hiring. At research driven institutions, your record of exploration and publication may be all-important. At schools that value teaching, your classroom expertise will be more valued.

What qualifications do you need to be a professor?

Though a master’s to start, and then eventually earning a doctorate, is the general rule for full-time tenure positions, here are no state or national standards for teaching college. The question is only truly answered by college hiring committees. Every school is different. They value different qualities ranging from research experience to real-world know-how. And it can differ from job to job or even year to year.

The most important quality you need when figuring out how to become a college professor may be your desire to learn. If you want to get your students interested in the material, you need to live and breathe it yourself. Academia is all about the process of expanding and understanding new knowledge. You’ll never fit into the field if you don’t have a passion for that.

5. Earn Tenure at Your University

Tenure is the end of the line for college professors. While almost any other kind of job can fire you with or without cause, once a professor has tenure, they are all but assured a position for life. Tenure insulates the academic community from trends and fads, allowing unpopular opinions to be expressed and unusual lines of research to be pursued. These are the hallmarks of liberal thinking and a liberal education.

But you have to earn that kind of freedom.

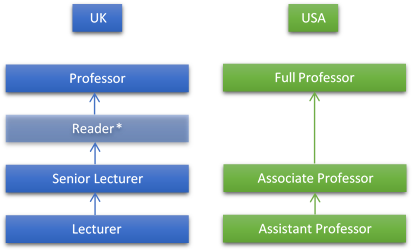

That first involves getting a fixed-term contract that offers possible tenure. It probably won’t be your first professorship, so you can expect to jump around between a few schools before it comes up.

That contract will mark you as an assistant professor, starting the long road to tenure. You will teach for a few years at that level, being observed by your department and undergoing evaluation by both students and other professors.

Assuming you survive that process, you will earn promotion to associate professor. This means a salary bump but also increased scrutiny for several more years. Your teaching, research, and publication accomplishments will all be weighed during this period. You may also take on additional administrative responsibilities in your department, and be evaluated in your performance.

In the end, a tenure committee of other faculty will decide whether or not you are worthy of becoming a full tenured professor.

Do professors make good money?

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, in 2020 the median salary for postsecondary teachers, the category that college professors are included in, was $80,790 per year.

But that also includes educators at vocational schools and other training academies outside of traditional colleges. The top ten percent of the group make excellent money, over $180,360 per year. The field you teach in can also affect your salary, with in-demand areas like law, economics, and engineering commanding six-figure median salaries.

Is a college professor a good career?

Like any career, becoming a college professor can be great if it delivers what you are looking for in a job. It’s perfect for people who enjoy exploring intellectual ideas, passing them on to students, engaging in cutting-edge research, and discussing it with other academics. Professors have tremendous flexibility in their personal schedules and in their freedom to teach topics that interest them. They have to be self-motivated and enjoy engaging with students. The opportunity to take long sabbaticals without risk of losing your job is also a big benefit that many enjoy.

- Share on twitter

- Share on facebook

Career advice: how to transition from PhD student to senior lecturer

Publish before your viva, distinguish opportunities from time-drains and have a strong online profile, says helen coleman.

- Share on linkedin

- Share on mail

I started my PhD in September 2006 and 10 years later I was promoted to senior lecturer – having made the obligatory jumps to postdoctoral research fellow and lecturer along the way.

While I’m aware of how fortunate I am, these transitions were also the result of a lot of hard work. Over the years, I have read lots of blogs and attended career advice sessions. While all of these were helpful, I do feel that there is a gap in advice on how to transition between stages.

PhD to postdoc

Establish a good relationship with your PhD supervisors One very good reason is that your supervisors will be providing references for you for years to come.

If possible, publish before your viva There is one part of your CV that future employers will always jump to: the publications section. The general rule of thumb in our department is to aim for two papers before your viva – although this can vary according to your subject. I published six peer-reviewed articles from my PhD thesis, five of them before my viva. I have no doubt that this helped me to be more competitive when going for future postdoc interviews.

Promote yourself within the department, but not at the expense of others It’s important to become known within your department. Where possible, work from the office, have lunch with your colleagues, not your computer screen, attend seminars, arrange meetings and volunteer for teaching and other opportunities. However, the addendum to this is equally important – do not talk down other PhD students in order to promote yourself.

Don’t stick to the same area of research It's vital to have a working knowledge of more general research being conducted in your department and beyond. My own PhD topic was nutrition and cancer, but I also got to know about pharmacoepidemiological methods and qualitative research – the PhD topics of my closest office friends. I have since applied both methodologies to my subsequent postdoc and academic research studies.

Search our database of more than 7,000 global university jobs

Postdoc to lecturer

Be vocal, persistent and resilient Those around you cannot second-guess your career objectives. You must vocalise them at appropriate times, such as appraisals. If you get rejected from your first academic interview, ask for feedback, make adjustments and apply again at the next opportunity.

Be productive – continue to publish This is still the first part of your CV that future employers will look at.

Funding starts to come into the equation Even if you have not been successful in obtaining funding as an independent principal investigator, being involved in grant applications or having a fellowship will make a huge difference. Apart from anything else, you will gain a realistic insight into what you will need to do as a lecturer.

Distinguish opportunities from time-drains If you are approached about an opportunity, have a think first before agreeing to it. Will it bring any additional skills to your CV? Will the time involved be worthy of the output? If the answer is no, it may be better to turn it down.

Lecturer to senior lecturer

Become more independent As you transition from early career to mid-career researcher, the atmosphere subtly changes from supportive and collaborative to competitive. Be wary of colleagues who do not respect your work, or who wish to hold back your development. It took me almost two years to realise that when you are a more senior academic, your department increasingly wants additionality, not collegiality. I purposely steered my research interests in a direction that overlapped to a lesser extent with that of my colleagues.

Have a strong online profile As you begin to work more independently, your colleagues will become less familiar. Attending internal seminars, while still important, will not help you as much as before. Now, people will be searching for you on Google, LinkedIn and Twitter. For that reason, I maintain and regularly update my online profile on my institution page and stay active on social media. How will others identify you as a collaborator if they do not know what you do?

Escapism is important While most people may see my one-hour commute as a waste of time, I see it as an opportunity to think about the day ahead or wind down on my way home. During my three-year probation period as a lecturer, I also started a new sport that involved training and playing matches three times a week. This downtime will become increasingly important to maintaining your well-being as your work life becomes increasingly busy.

As you go up the ladder, give others a helping hand I am a mentor for a lecturer-level colleague, and at the same time I am a mentee receiving guidance from a professor/pro vice-chancellor who is part of the same scheme. Mentoring is non-negotiable, in my view. It is our duty to continue to mentor others as we progress in our careers.

Helen Coleman is senior lecturer in cancer epidemiology at the Centre for Public Health at Queen’s University Belfast .

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Reaching the next rung of the academic career ladder

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login

Related articles

Is mentoring the elixir of academic life?

The importance of senior faculty advising junior colleagues on their career trajectories is increasingly emphasised. But is guidance – and the giving of it – being fairly shared? Should mentoring schemes be formalised? And are they really enough? Seven academics have their say

NIH raises postdoctoral salaries, but below target

Top US funding agency manages record increase in key programme for younger scientists, and sees gains in overall equity, while absorbing net cut in its annual budget

How to win the citation game without becoming a cynic

Boosting your publication metrics need not come at the expense of your integrity if you bear in mind these 10 tips, says Adrian Furnham

Featured jobs

From PhD to assistant professor: Applications and interviews

Three academics reflect on how they got on the tenure track.

- Post a comment

You’ve almost made it: the courses, comps, proposal are all under your belt. You’re polishing your dissertation and practicing your defence. You’re exhausted and excited. It’s a time for celebration. A time for looking back at what you have accomplished and for looking forward into the unknown. This transition phase from grad student to faculty member can be fraught with questions: How will I navigate the transition out of grad school? Should I do a postdoc? Am I cut out for academia? How can I best position myself? What do I really want? Below are three unique perspectives from recently hired assistant professors at Canadian research-intensive universities. Together they have asked these questions and more as they navigated their journey from PhD to applying, interviewing, and finally securing tenure-track academic positions. They share a taste of their experience here to shed a light on the challenges and successes of entering academia.

Making changes to my expectations and strategies

Ee-Seul Yoon, assistant professor, University of Manitoba

In the last year of my PhD, I was probably a typical PhD candidate, looking for job posts on the University Affairs and Academic Keys websites. Once I found a suitable post, I would spend about a week completing my application package with a self-made checklist, and then send it off. After having applied for a dozen jobs, which resulted in two on-campus interviews, I began to realize that having successfully completed a PhD from a research-intensive university and having some teaching experience were insufficient to land a tenure-track assistant professor position in North America – because there were so many other PhD graduates just like me. So, when I graduated and did not have an academic position to move onto, I had to make some changes.

First, I had to face the reality that I may not become an academic after all, and that I may have to look for non-academic jobs. If I were to continue to pursue an academic career, I would have to continue to publish more, even though I had already published a few articles. I could see the value of a postdoctoral position, although I was hesitant about doing one because it was temporary and did not provide a definite job prospect at the end. However, when I received a two-year SSHRC postdoctoral fellowship award, I took it and worked on publishing, starting a new research program, and engaging in exciting international service opportunities. In addition, I looked beyond my city (Vancouver) for a position, which caused my family some anxiety, especially my spouse, who faced the possibility of having to restart his career. Finally, before I was invited for on-campus job interviews, I thoroughly researched how my academic work could benefit the community and the public, which the university is purported to serve. Overall, I learned that being on the academic job market requires being open to changing one’s initial expectations and strategies.

Listening to the small voice within

Judith Walker, assistant professor, University of British Columbia

I hung up the phone and burst into tears. Am I not cut out for academia? Do I not want this job? I questioned, reflecting on my disappointing Skype interview for a faculty position at UBC, the same place I had completed my PhD one year earlier. I had literally gone blank in the face of an onslaught of questions by the same people who had previously been my teachers and mentors. Bound to Vancouver by my partner’s career, I had limited my job search to the two major research universities in BC’s lower mainland, UBC and Simon Fraser University. As an international student who had then been granted a three-year work permit, I was ineligible for tri-council funding and had instead taken a part-time postdoc contingent on multiple grant funding in the faculty of dentistry at UBC, engaging in educational research in new and familiar ways. Throughout my three years there I also taught online for UBC and the University of Calgary, as well as took on other contracts to make up a full-time job.

At the time, I believed I was biding my time until I got a “real” job and could finally enter delayed adulthood. In retrospect, these were real jobs and enriching educational experiences that have informed who I am as a scholar. After the failed Skype interview, I sought the support of a career coach. I allowed myself the time and space to pursue an existential examination of vocation, to “let my life speak” as educator and author Parker Palmer puts it . In other words, to slow down and listen to the call of vocation so to better understand what I wanted to do with my life. Over a year later, I received another interview for a similar job at UBC. This time, I was more secure in who I was and what I wanted, recognizing that I too could belong at the institution.

Looking both ways

Graham W. Lea, assistant professor, University of Manitoba

As I neared the end of my PhD I was fortunate to secure a postdoctoral fellowship. This opportunity became a space for me to transition from my dissertation to engage in exciting and meaningful new research opportunities. I hoped they would prove fertile ground in which I could sow the seeds of my early career research and eventual employment.

During my fellowship, I taught at several universities, including a short intensive stint in a refugee camp in Kenya. The preparations for Kenya were intense: designing courses, planning logistics, and mentally bracing myself for what I knew would be a challenging teaching assignment. About two weeks before I was to leave for Kenya, I received an invitation for an immediate interview at a prestigious European university. Even if I didn’t get the job, it would be great exposure – the external reviewer on the committee was one of the leaders in my field. I tried to rearrange my flights to Kenya, but the short notice meant I would have to fly from Canada to Europe, attend the interview, return to Canada, and then travel back to Europe and on to Kenya all within about a week. Despite seeing exhaustion on the horizon, I packed my bags and flew off to the interview.

Near the end of the grueling day of interviews and presentations I was asked: what are some of your goals for your first year should you secure this position? After listing my prepared remarks my exhausted mind let slip “… and I want to work on developing a positive work-life balance.” One of the interviewers tilted her chair back and laughed saying, “There’s no such thing.” With that, I received an unexpected glimpse into the culture of the university that caused me to question if this was the right place for me. In the end, I wasn’t offered the position; but I did learn that it’s not only the candidate who’s being interviewed on interview day. For my subsequent (and eventually successful) interviews, in addition to my set of anticipated responses, I came prepared with questions for the committee to help me to understand the environment I might be entering.

Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- Assistant Professor vs Associate Professor: What's the Difference

Should I become a professor? Success rate 3% !

When organizing career events for PhD students and postdocs, we realize that most young researchers envision an academic career. They are shocked when we confront them that only 3-5% of them will actually end up as academic staff.

ONLY 30% OF ALL DOCTORATE HOLDERS STAY IN ACADEMIA – MOSTLY AS POSTDOCS

The Centre for Research & Development Monitoring ( ECOOM ) follows the career paths of young researchers in the Dutch-speaking part of Belgium. Their data indicate that about 30% of young Belgian researchers in natural sciences, engineering, and life sciences continue their academic careers (ECOOM-Belspo: CDH survey 2010) .

In a nice summary by PabloAMC , several articles were reviewed that corroborate this percentage: around 30% of PhD holders in the U.K. and 34% in the U.S. remain in academia.

Thus, about 70% find a job outside academia after their graduate programs – for example, in industry, government, or hospitals. In humanities and social sciences, the percentage of Ph.D. graduates who stay in academia for three years after their Ph.D. was about 50% (ECOOM-Belspo: CDH survey 2010).

UP TO 33% OF ALL POSTDOCS STAY IN ACADEMIA

Data from Belgian universities indicate that most young researchers who stay in academia become postdoctoral researchers. Only a few take over staff positions, such as organizers of doctoral schools or specific study programs.

Of these postdoctoral researchers, only 1 in 10 finally reach a long-term academic position as a professor. Thus, approximately 10% of all postdocs become tenured in Belgium.

Interestingly, in the United States, the numbers appear to be higher:

Andalib et al., 2018 reported that 17% of U.S. postdocs from all science fields (including health and social sciences) obtained tenure-track faculty positions within ten years.

Kahn and Ginter, 2017 found that 21% of U.S. biomedical postdocs reached tenure-track status within ten years.

Denton et al., 2022 reported that 23% of life sciences postdocs and 33.2% of physical sciences and engineering postdocs in the U.S. were employed in tenure-track faculty positions within 5–6 years following degree completion. The authors carefully mention that the different percentages may be influenced by the longer duration of the earlier studies (10 years versus 5–6, respectively).

It is important to note that these data included Assistant Professor, associate professor, and full professor positions.

To my knowledge, no data is available comparing the chances of becoming an adjunct professor who works for a university on a contract basis versus a tenured professor holding a full-time position until retirement.

Thus, about 67 to 90% of postdoctoral researchers find jobs in the industry or public sector – and NOT in academia! Surprisingly, this fact is not known by most young researchers!

UP TO 80% OF ALL POSTDOCS HOPE TO PURSUE AN ACADEMIC CAREER, ALTHOUGH ONLY 33% OR LESS WILL WORK IN ACADEMIA

We conducted a survey in Belgium to investigate postdoctoral researchers’ expectations and needs (Belgian Postdoc Survey 2012). We received feedback from 413 postdoctoral researchers from all scientific domains at Belgian universities.

Surprisingly, nearly 80% of all postdocs hoped to pursue a career in academia, although only about 10% ended up in higher education.

Nearly a decade later, 63% of all postdocs surveyed in the 2020 postdoc survey by the journal Nature stated that they hope to pursue a career in academia . The majority of postdocs had pessimistic career expectations: 39% reported feeling ‘somewhat negative’ and 17% ‘extremely negative’ about their job prospects. 74% of the postdocs consider their job perspectives worse than those of previous postdoc generations.